Abstract

Background: The efficacy and safety of duloxetine, a dual reuptake inhibitor of serotonin and norepinephrine at the recommended starting dose, have been demonstrated in the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD) in men and women and in the treatment of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) in women. Since the mechanism of action of duloxetine in the treatment of SUI is believed to be related to enhanced urethral closure forces, it is important to clarify the risk of acute urinary retention.

Method: The relationship between duloxetine and obstructive voiding symptoms was examined in 8 double-blind, 8- to 9-week, placebo-controlled studies and 1 open-label study in men and women treated for MDD with duloxetine 40 to 120 mg/day and in 4 double-blind, 12-week, placebo-controlled studies and 4 ongoing open-label studies in women treated for SUI with duloxetine 80 mg/day.

Results: In 378 men and 761 women with MDD treated in placebo-controlled trials, 0.4% (4/1139; 3 men and 1 woman) of those treated with active medication reported subjective urinary retention versus none (0/777) of those treated with placebo (p = .15). In 958 women with SUI treated with duloxetine in placebo-controlled trials, none reported subjective urinary retention. Overall, in the duloxetine placebo-controlled clinical studies in the treatment of MDD and SUI, obstructive voiding symptoms (reported either as subjective urinary retention or other obstructive voiding symptoms) occurred more often in patients receiving duloxetine (1.0%, 20/2097) than in patients receiving placebo (0.4%, 6/1732) (p < .05). Of the 4719 MDD and SUI patients treated with duloxetine in placebo-controlled and ongoing open-label studies, 2 men and 1 woman discontinued because of obstructive voiding symptoms. Although such an evaluation was not required by protocol, no cases of objective acute urinary retention with postvoid residual urine verified with a bladder scan or requiring catheterization were reported in patients treated with duloxetine.

Conclusion: Duloxetine treatment in women and men with depression and in women with SUI was rarely associated with obstructive voiding symptoms, and no subjects had objective acute urinary retention requiring catheterization.

Obstructive voiding symptoms, including urinary retention, are rare in women and are usually related to pharmaceutical agents; genital organ prolapse; neurologic conditions such as multiple sclerosis and Parkinson's disease; or decreased bladder contractility resulting from diabetes mellitus1 or vesico-urethral sphincter dyssynergia.2–4 Vesico-urethral sphincter dyssynergia is related to the lack of striated urethral sphincter relaxation when the bladder contracts during voiding. The condition is rare and its pathophysiology is poorly understood, but in some women with the condition, particularly younger women, it may be due to neuronal damage. The disorder may reverse.

Obstructive voiding difficulties in men are common and often associated with age-related benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), although no significant correlation between the size of the prostate gland and urinary flow has been established.5 Other risk factors in men include pharmaceutical agents, prostate cancer, neurologic disorders such as multiple sclerosis and Parkinson's disease, and diabetes mellitus.

Different pharmaceutical agents such as opiates, antihistamines, α-adrenoceptor agonists, ganglion blockers, phenothiazines, and monoamine oxidase inhibitors have been associated with obstructive voiding symptoms in both genders, either as the primary cause or as a contributor worsening a preexisting condition.6 Continuous anticholinergic relaxation of the bladder muscle or continuous adrenergic contraction of the smooth urethral sphincter muscle is usually believed to explain obstructive voiding symptoms associated with these agents.

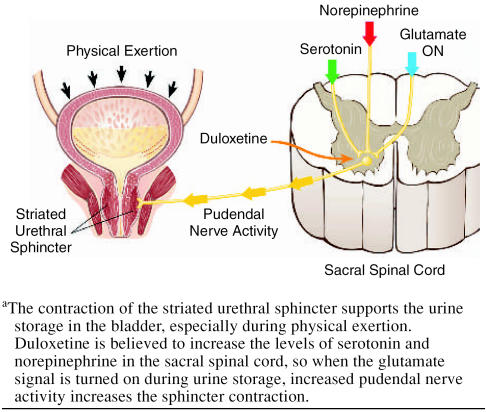

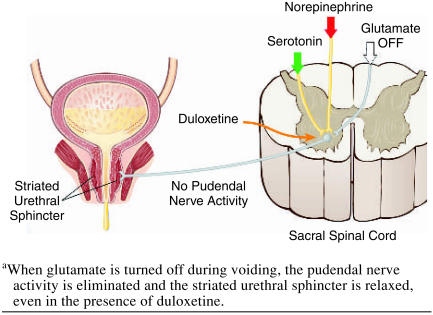

Duloxetine is currently being investigated for the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD)7–10 and female stress urinary incontinence (SUI).11–14 Duloxetine is a dual serotonin (5-HT) and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) at the expected starting dose (60 mg q.d. for MDD and 40 mg b.i.d. for SUI).15,16 Duloxetine has been demonstrated to significantly increase bladder capacity and striated urethral sphincter muscle activity through central actions in the spinal cord in cats, but only during the storage phase of the micturition cycle,17 presumably in the presence of the neurotransmitter glutamate (Figure 1). The increased levels of 5-HT and norepinephrine in the sacral spinal cord are not believed to augment the gluta-matergic signal to the urethral striated sphincter during voiding17,18 (Figure 2), and therefore the risk of obstructive voiding symptoms should be negligible. A similar central mechanism in women is believed to explain the clinical efficacy of duloxetine as a treatment for SUI established in 4 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled 12-week studies enrolling 1913 women (aged 22–83 years).11–14 However, since duloxetine improves urethral closure, it is of interest to clarify any potential risk of inducing acute urinary retention.

Figure 1.

Urine Storage During Physical Exertiona

Figure 2.

Voidinga

Acute urinary retention is defined as having a painful, palpable, or percussible bladder and being unable to pass any urine.19 Acute urinary retention can be objectively verified with a bladder scan or require urethral catheterization.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Major Depressive Disorder Studies

The efficacy and safety of duloxetine as a treatment for MDD were examined in 8 double-blind, 8- to 9-week placebo-controlled studies (two phase 2 studies and six phase 3 studies) with 1916 patients (aged 18–77 years) (1139 receiving duloxetine, 777 receiving placebo) and an open-label study (phase 3) with 1279 patients (aged 18–87 years). Six of these multicenter trials were conducted in the United States, and 2 were international studies. Data in this article are based on post hoc secondary analyses and data on file at Eli Lilly and Company (Indianapolis, Ind.). The total of 2418 patients treated with duloxetine represents approximately 1099 patient-years of exposure. The median duration of treatment with study drug was 91 days, and 993 patients (41.1%) received duloxetine for at least 180 days. All men and women met the eligibility criteria for MDD as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV). A major depressive episode implies a prominent and relatively persistent (nearly every day for at least 2 weeks) depressed mood or loss of interest/pleasure in nearly all activities that interferes with daily functioning and includes different psychosocial behaviors. Duloxetine, at a dose of 40 to 120 mg, was given daily as active treatment in either single or divided doses.

Stress Urinary Incontinence Studies

The efficacy and safety of duloxetine as a treatment for female SUI were assessed in 1913 women (aged 22–83 years) enrolled in 4 double-blind, placebo-controlled studies (one phase 2 study and three phase 3 studies), the details of which have been previously reported.11,12,14,20 Patients were randomly assigned to receive duloxetine 40 mg b.i.d. (N = 958) or placebo (N = 955) for 12 weeks. In addition, data were obtained from 4 ongoing open-label studies of duloxetine 40 mg b.i.d. in 1877 women (aged 20–87 years). Three of the ongoing open-label studies were extensions of the phase 3 studies; one open-label study in 658 women was not preceded by a placebo-controlled study. In total, 2301 women were exposed to duloxetine, with 818 having more than 6 months of exposure and 191 having more than 12 months of exposure. All women included in the studies met the eligibility criterion for SUI: the involuntary loss of urine associated with coughing, sneezing, or physical exertion, as defined by a diary, a stress pad test, a cough test, and a simple filling cystometry.12

Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia Study

The efficacy and safety of duloxetine in men with significant obstructive uropathy and irritative bladder symptoms were assessed in 1 placebo-controlled study evaluating 91 patients (aged 40–85 years; 47 randomly assigned to duloxetine and 44, to placebo) for 4 to 8 weeks. After 4 weeks, irritative bladder symptoms such as frequency, urgency, and nocturia reported by 22 men did not respond to placebo, and the patients were then treated with active medication for an additional 4 weeks, making the total number of men treated with duloxetine 69 (data on file, Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, Ind.). All men included in the study met eligibility criteria for mild-to-moderate BPH (as defined by the presence of irritative symptoms [frequency, urgency, nocturia] and mild-to-moderate obstruction during uroflowmetry) and either were candidates for or were already receiving medical therapy for BPH. Duloxetine at a dose of 30 to 40 mg was given daily as active treatment. In this study, the irritative symptoms of BPH did not improve with duloxetine treatment.

Coding of Adverse Events

Adverse events were elicited by nonprobing inquiry at each visit and were recorded regardless of perceived causality. Events were registered as treatment-emergent adverse events if occurring for the first time or worsening during therapy following baseline evaluation. All levels of event terms, from the patients' wording as reported to the investigators to the overall final terms in the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA), were searched for matches related to obstructive voiding symptoms in the MDD and SUI studies and matches related to urinary retention in the BPH study. This article uses the MedDRA preferred terms for obstructive voiding symptoms: urinary retention, difficulty in micturition, dysuria, micturition disorder, strangury, urinary hesitation, and decreased urine flow. Dysuria is defined as painful or difficult urination, and although some of these patients may not have obstructive voiding symptoms, this term has been included too. The preferred term urinary retention was identical to the actual term reported by the patient and registered by the investigator, except in 5 cases where the symptom was reported as incomplete bladder emptying.

Only treatment-emergent events are reported in this review. If urinary retention was not verified objectively according to the definition and no bladder scan or catheterization was performed, it was considered subjective. However, verification of urinary retention was not required by study protocol. Since different obstructive voiding symptoms may have been reported on separate occasions by the same patient, the sum of the adverse events reported in the article is expected to be higher than the sum of patients with obstructive voiding symptoms.

National or institutional review boards at each study site approved the protocols, and all patients provided signed informed consent prior to study participation.

Statistics

Fisher exact tests or Pearson χ2 tests were used when appropriate to assess the significance of association. Statistical significance was defined as p < .05.

RESULTS

Major Depressive Disorder Studies

Placebo-controlled studies.

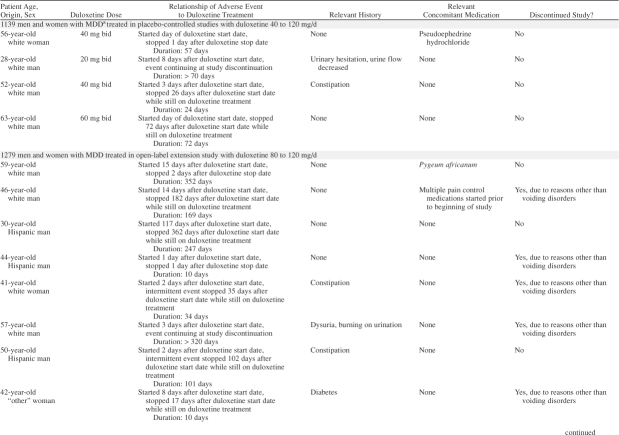

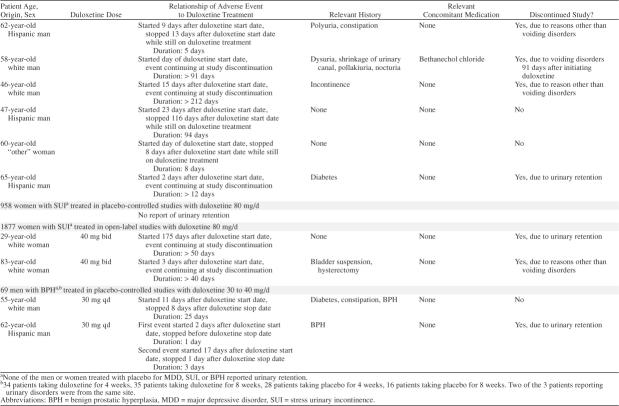

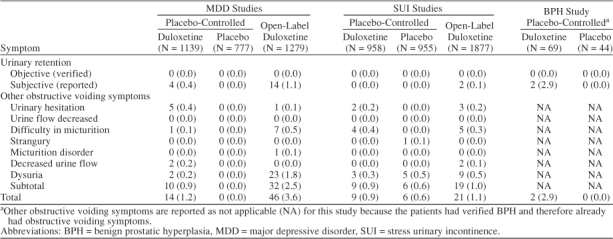

In the placebo-controlled studies conducted with women experiencing MDD, subjective urinary retention was reported in 0.1% (1/761) of patients treated with duloxetine versus none (0/530) treated with placebo (p = 1.0) (Tables 1 and 2). Dysuria was the only other obstructive voiding symptom reported in 0.3% (2/761) of women treated with active medication versus none (0/530) treated with placebo (p = .50). In men with MDD, subjective urinary retention was reported by 0.8% (3/378) of those treated with duloxetine versus none (0/247) treated with placebo (p = .28). Other obstructive voiding symptoms (urinary hesitation, urine flow decreased, and difficulty in micturition) were reported in 1.6% (6/378) of men treated with duloxetine versus none (0/247) treated with placebo (p = .09).

Table 1.

Summary of Reports of Urinary Retention in Duloxetine-Treated Patients

Table 1.

Summary of Reports of Urinary Retention in Duloxetine-Treated Patients (cont)

Table 2.

Summary of Obstructive Voiding Symptoms Across Duloxetine Studies, N (%)

In both women and men with MDD treated in placebo-controlled trials, 0.4% (4/1139) of those treated with active medication reported subjective urinary retention versus none (0/777) of those treated with placebo (p = .15). Subjective urinary retention or other obstructive voiding symptoms were reported significantly (p < .01) more often by men (1 with preexisting prostate conditions) (2.1%, 8/378) than by women (0.4%, 3/761) with MDD treated in placebo-controlled trials.

Preexisting prostate conditions were reported in 2.4% (9/378) of men with MDD treated with duloxetine in placebo-controlled trials (2 had BPH, 5 had enlarged prostate, and 2 had prostatitis). Obstructive voiding problems (decreased urinary stream strength and urinary hesitation) were reported in 1 (11.1%, 1/9) of these men.

None of the women or men reporting subjective urinary retention or other obstructive voiding symptoms were catheterized or had a bladder scan performed to determine acute urinary retention or postvoid residual urine. None of the women or men discontinued from the studies because of obstructive voiding symptoms.

Open-label study.

In the open-label study21 conducted with patients experiencing MDD, subjective urinary retention was reported in 0.3% (3/928) of women and 3.1% (11/351) of men treated with duloxetine. Other obstructive voiding symptoms were reported in 1.4% (13/928) of women and 5.4% (19/351) of men. These other obstructive voiding symptoms included difficulty in micturition, micturition disorder, urinary hesitation, and dysuria. Two men reported both urinary retention and dysuria, while 1 man reported both difficulty in micturition and dysuria. Overall, obstructive voiding symptoms (including subjective urinary retention) were reported in 1.7% (16/928) of women and 8.5% (30/351) of men.

In patients with MDD treated with duloxetine in the open-label trial, subjective urinary retention or other obstructive symptoms were reported significantly (p < .001) more often by men (7.7%, 27/351) than by women (1.7%, 16/928).

Preexisting prostate conditions were reported in 2.3% (8/351) of men with MDD treated with duloxetine in the open-label study (4 men had BPH, 2 had prostate hyperplasia, 1 had prostate disorder, and 1 had prostatitis). Obstructive voiding symptoms were reported in none of these men.

None of the women or men reporting subjective urinary retention or other obstructive voiding symptoms reported being catheterized or having a bladder scan performed to determine acute urinary retention or postvoid residual urine. While no women discontinued from the study because of obstructive voiding symptoms, 2 men reporting subjective urinary retention (1, additionally dysuria) discontinued.

A 58-year-old man reporting subjective urinary retention within the first day and dysuria within the second day of starting duloxetine was prescribed bethanechol chloride (pharmacologically related to acetylcholine) because of dysuria 32 days after initiating duloxetine. He remained in the study for a total of 91 days after the onset of urinary retention at which time he discontinued because of a variety of obstructive voiding symptoms including dysuria (Table 1).

A 65-year-old diabetic man reported subjective urinary retention within 2 days of starting duloxetine and discontinued because of this complaint after 12 days on treatment with duloxetine.

Stress Urinary Incontinence Studies

Placebo-controlled studies.

In the placebo-controlled studies conducted with women experiencing SUI, none reported subjective urinary retention. Other obstructive voiding symptoms were reported in 0.9% of women (9/958) treated with duloxetine versus 0.6% (6/955) treated with placebo (p = .60). These other obstructive voiding symptoms included difficulty in micturition (4 receiving duloxetine, 0 receiving placebo), urinary hesitation (2 receiving duloxetine, 0 receiving placebo), strangury (0 receiving duloxetine, 1 receiving placebo), and dysuria (3 receiving duloxetine, 5 receiving placebo). None of the patients reporting obstructive voiding symptoms were catheterized or had a bladder scan performed to determine postvoid residual urine. None discontinued because of other obstructive voiding symptoms.

Open-label studies.

In the ongoing open-label studies performed in women with SUI, subjective urinary retention was reported in 0.1% (2/1877) of women treated with duloxetine; 1 woman discontinued because of subjective urinary retention (Table 1). Other obstructive voiding symptoms were reported in 1.0% (19/1877) of women. These other obstructive voiding symptoms included difficulty in micturition (number of events = 5), urinary hesitation (3), urine flow decreased (2), and dysuria (9). One woman reported both difficulty in micturition and urinary retention. None of the patients reporting subjective urinary retention or other obstructive voiding symptoms were catheterized or had a bladder scan performed to determine postvoid residual urine. None discontinued because of other obstructive voiding symptoms.

Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia Study

Subjective urinary retention was reported in 2.8% (2/69) of duloxetine-treated men with known obstructive voiding symptoms due to BPH versus none (0/44) of those treated with placebo (p = .5) (Table 1). One male patient who reported subjective urinary retention discontinued after the second episode (Table 1). None of the patients reporting subjective urinary retention were catheterized or had a bladder scan performed to determine acute urinary retention or postvoid residual urine.

Overall Results

In the placebo-controlled clinical studies in men and women with MDD and women with SUI treated with duloxetine 40 to 120 mg/day, obstructive voiding symptoms (reported as either urinary retention or other obstructive voiding symptoms) occurred significantly more often in patients receiving duloxetine (1.0%, 20/2097) than in patients receiving placebo (0.4%, 6/1732) (p < .05). In the entire population of 4788 men and women treated with duloxetine 30 to 120 mg/day in placebo-controlled or open-label extension clinical studies (2418 with MDD, 2301 with SUI, and 69 with BPH), 22 patients (0.5%) reported subjective urinary retention. Of those 22 patients, 19 (86.4%) reported subjective urinary retention within approximately 2 weeks of initiating duloxetine treatment (Table 1). The duration of the symptom varied from a few days to months (Table 1). Some of these patients were taking concomitant medications that independently could increase the risk of urinary retention or other voiding symptoms (Table 1).

Overall, of the 4788 patients treated with duloxetine, 3 men and 1 woman (0.08%) discontinued because of obstructive voiding symptoms. Although such an evaluation was not required by study protocol, no cases of objective acute urinary retention, defined as the accumulation of urine within the bladder because of the inability to urinate and verified with a bladder scan or requiring catheterization, were reported.

DISCUSSION

Duloxetine does not seem to be associated with objective acute urinary retention in men and women treated for MDD or in women treated for SUI. A small but significant number of men and women did report some obstructive voiding symptoms when treated with duloxetine. Only 0.08% (4/4788) of men and women treated with duloxetine discontinued the studies because of obstructive voiding symptoms. In the few patients reporting subjective urinary retention, none required catheterization or a bladder scan. However, as previously stated, verification of subjective urinary retention was not required by study protocol. In those reporting obstructive voiding symptoms, 86.4% (19/22) of the patients reported subjective urinary retention within 2 weeks of starting treatment (Table 1). The reported duration of the symptoms varied from days to months (Table 1). The higher number of women in the MDD studies reporting subjective urinary retention compared with women in the SUI studies may reflect that the reported severity of obstructive voiding symptoms is interpreted differently in the psychiatric setting compared with the urologic or gynecologic settings. The higher dose range of duloxetine (40–120 mg/day) in men and women treated for MDD compared with women treated for SUI (80 mg/day) may have played a role. Though significantly more men than women in the MDD studies reported subjective urinary retention, previous prostate condition in depressed men or in men with verified BPH did not seem to play a major role in the reported occurrence of duloxetine-associated subjective urinary retention; however, the duloxetine dose was lower in the BPH study.

The centrally acting mechanism of duloxetine seems to explain why no patients experienced acute urinary retention. During urinary storage, pudendal motor neurons activate the urethral striated sphincter via the action of the neurotransmitter glutamate. Descending 5-HT and norepinephrine pathways from the brain to the ventral horn of the sacral spinal cord (Onuf's nucleus) modulate or enhance the activity of the neurons in the pudendal nerve only when the glutaminergic neurons are active17,18 (Figure 1). Duloxetine increases the levels of 5-HT and norepinephrine in the synaptic cleft of Onuf's nucleus, thereby enhancing the glutamatergic signal to the urethral striated sphincter muscle, but only during the storage phase of the micturition cycle.17 Duloxetine does not interfere with normal voiding because the striated urethral muscle is under voluntary control and relaxes when the glutamate signal is turned off (Figure 2). Duloxetine has no significant peripheral effect on the smooth urethral sphincter because of the negligible affinity for those adrenergic receptors responsible for the contraction.15 Though animal studies have shown that duloxetine reduces bladder detrusor instability, this reduction is not associated with a peripheral anticholinergic effect on the bladder muscle,17 since duloxetine has negligible affinity for cholinergic receptors.15 Duloxetine's effect on the bladder is believed to represent another central mechanism; it modulates afferent bladder stimuli17 with no risk of inducing incomplete bladder emptying, since a normal detrusor contraction is maintained in response to an increased bladder volume.17 In conclusion, the risk that duloxetine will cause urinary retention seems limited. However, some patients may experience weak obstructive voiding symptoms most likely caused by peripheral adrenergic activity affecting the smooth urethral muscle or modifying the unique bladder-urethra synergy.

Since other pharmaceutical agents have been associated with obstructive voiding symptoms, coadministration with duloxetine may theoretically represent an increased risk of provoking voiding disorders.

Tricyclic antidepressants such as desipramine may cause peripheral symptoms such as urinary retention, constipation, tachycardia, or blurred vision.22,23 Urinary retention is most likely caused by the anticholinergic effects, which inhibit contraction of the detrusor bladder muscle24 in addition to inhibiting norepinephrine reuptake in the adrenergic nerve endings supplying the smooth urethral sphincter muscle. In a drug-drug interaction study with duloxetine and desipramine conducted in 7 healthy male and 9 female volunteers (aged 21–63 years),25 a single dose of desipramine 50 mg/day was added to steady-state duloxetine 60 mg b.i.d. One subject reported urinary hesitation the second day after starting desipramine treatment. No subjects reported subjective urinary retention. The risk of severe obstructive voiding symptoms in this small sample of healthy patients receiving both duloxetine and desipramine seems limited, though caution should be used if tricyclics are prescribed alone26 or in combination with duloxetine, especially in patients with a history of urinary retention.

Selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, such as reboxetine, belong to a new class of antidepressants and have been reported to cause urinary hesitancy, urinary retention, and hypertension in some patients,27 presumably via a constant nonselective peripheral effect on the adrenergic nerve endings on the smooth muscle cells in both the urethral sphincter and the arteries. A drug-drug interaction study with duloxetine and a selective norepinephrine re-uptake inhibitor has not been conducted. Although there is no basis to determine if there is an increased risk in coadministering these agents, caution should also be used in these cases.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) such as fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline that are indicated for MDD have negligible anticholinergic affinity in contrast to older antidepressants.28,29 The SSRIs have no significant effect on the striated urethral rhabdosphincter in animal studies17 and are rarely associated with obstructive voiding symptoms.30,31 Duloxetine, fluoxetine, and paroxetine are metabolized by the hepatic cytochrome P450 (CYP) system CYP2D6. The coadministration of both an SNRI and an SSRI may lead to increased levels of both 5-HT and norepinephrine, but whether this represents an increased risk of obstructive voiding symptoms is unknown. A drug-drug interaction study with duloxetine and paroxetine was conducted in 12 healthy male volunteers (aged 21–27 years).25 During a 5-day period, paroxetine 20 mg/day was coadministered with steady-state duloxetine 40 mg q.d. In this small sample of men, none experienced any obstructive voiding symptoms.

Other SNRIs such as venlafaxine and milnacipran (an SNRI available in Europe) are indicated for the treatment of MDD,32 but not for SUI. In animal studies, venlafaxine has a less potent effect on the striated urethral sphincter33; however, a few cases of urinary retention have been reported in humans.34 According to the Physicians' Desk Reference,35 urination impairment was reported in more than 1% and urinary retention and dysuria in less than 1% of patients treated with venlafaxine. When 1871 men and women were treated with milnacipran for MDD, more than 2% reported dysuria. Dysuria was 1 of 5 adverse events occurring more frequently in the milnacipran-treated patients than in the placebo-treated patients.36 In another review, 7% of men treated with milnacipran reported dysuria, which was the second most common adverse event.37 As per the definition, all cases may not represent obstructive voiding symptoms, but it is likely that milnacipran, with its greater norepinephrine than 5-HT reuptake inhibition compared with duloxetine, may induce an increased peripheral stimulation of the α1 receptors in the smooth urethral muscle, causing outlet obstruction.

Urinary retention due to extended bladder relaxation has been reported in anticholinergic (antimuscarinic) agents such as tolterodine and oxybutynin that are indicated for the treatment of urge incontinence.38 The therapeutic effect of anticholinergics is to decrease the tendency of the bladder to contract inappropriately by blocking acetylcholine binding at its peripheral (muscarinic) receptor on the bladder smooth muscle. An effect on the smooth or striated muscles of the urethra has not been documented. A drug-drug interaction study with duloxetine and tolterodine was conducted in 3 healthy male and 13 female volunteers (aged 21–54 years).25 Duloxetine 80 mg/day and tolterodine 4 mg/day were coadministered for 5 days. One patient reported difficulty in micturition on the first day and another patient on the third day, while one patient reported urinary hesitation on the second day. None reported urinary retention. The risk of obstructive voiding disorder in healthy patients receiving both duloxetine and tolterodine therefore seems limited, though caution should be used if tolterodine is prescribed alone39 or in combination with duloxetine in patients with history of urinary retention.

In conclusion, duloxetine was not associated with objective acute urinary retention requiring catheterization. The risk of other obstructive voiding symptoms seems limited, and the likelihood of patients stopping treatment for these reasons is very small. However, as in the case with any pharmaceutical agent that has the potential to induce or exacerbate an obstructive voiding symptom, duloxetine should be used cautiously in patients with a history of urinary retention or when used in combination with other agents known to cause urinary retention.

Drug names: desipramine (Norpramin and others), fluoxetine (Prozac and others), oxybutynin (Oxytrol, Ditropan), paroxetine (Paxil and others), sertraline (Zoloft), tolterodine (Detrol), venlafaxine (Effexor).

Acknowledgments

This manuscript was made possible with the participation of several investigators worldwide. The authors thank Pam Howard, R.N.; Simin Baygani, M.S.; Misty Odle, B.S.; Cynthia Hooper, M.A.; Janel Dawes, B.S.; Curtis Wiltse, Ph.D.; and Thomas C. Lee, M.A., at Lilly Research Laboratories, Indianapolis, Ind.

Footnotes

Supported by Eli Lilly and Co., Indianapolis, Ind. Images were provided by the Plexus Learning Design, Marblehead, Mass.

Dr. Viktrup and Ms. Pangallo are employees of Eli Lilly. Dr. Detke is an employee of and major stock shareholder in Eli Lilly. Dr. Zinner has been a consultant for Eli Lilly, Watson, Indevus, Schwarz Pharma, Pfizer, and Kyowa; has received grant/research support and honoraria from Eli Lilly, Watson, Indevus, Pfizer, and Kyowa; and has participated in speakers/advisory boards for Eli Lilly, Watson, Indevus, Schwarz Pharma, Pfizer, and Kyowa.

REFERENCES

- Olapade-Olaopa EO, Morley RN, and Carter CJ. et al. Diabetic cystopathy presenting as primary acute urinary retention in a previously undiagnosed young male diabetic patient. J Diabetes Complications. 1997 11:350–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin RJ, Swinn MJ, Fowler CJ. The neurophysiology of urinary retention in young women and its treatment by neuromodulation. World J Urol. 1998;16:305–307. doi: 10.1007/s003450050072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiseman OJ, Swinn MJ, and Brady CM. et al. Maximum urethral closure pressure and sphincter volume in women with urinary retention. J Urol. 2002 167:1348–1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaivas JG, Sinha HP, and Zayed AA. et al. Detrusor-external sphincter dyssynergia: a detailed electromyographic study. J Urol. 1981 125:545–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry MJ, Cockett AT, and Holtgrewe HL. et al. Relationship of symptoms of prostatism to commonly used physiological and anatomical measures of the severity of benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 1993 150(2, pt 1):351–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardozo L. Voiding Difficulties and Retention: Urogynecology. 1st ed. New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone. 1997 305–320. [Google Scholar]

- Detke MJ, Lu Y, and Goldstein DJ. et al. Duloxetine 60 mg once daily dosing versus placebo in the acute treatment of major depression. J Psychiatr Res. 2002 36:383–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detke MJ, Lu Y, and Goldstein DJ. et al. Duloxetine, 60 mg once daily, for major depressive disorder: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002 63:308–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein DJ, Mallinckrodt C, and Lu Y. et al. Duloxetine in the treatment of major depressive disorder: a double-blind clinical trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002 63:225–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemeroff CB, Schatzberg AF, and Goldstein DJ. et al. Duloxetine for the treatment of major depressive disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2002 36:106–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Kerrebroeck P, Abrams P, and Lange R. et al, and the Duloxetine Urinary Incontinence Study Group. Duloxetine versus placebo in the treatment of European and Canadian women with stress urinary incontinence. BJOG. 2004 111:249–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton PA, Zinner NR, and Yalcin I. et al. Duloxetine versus placebo in the treatment of stress urinary incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002 187:40–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dmochowski RR, Miklos JR, and Norton PA. et al. Duloxetine versus placebo for the treatment of North American women with stress urinary incontinence. J Urol. 2003 170:1259–1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millard R, Moore K, and Rencken R. et al, and the Duloxetine UI Study Group. Duloxetine vs placebo in the treatment of stress urinary incontinence: a four-continent randomized clinical trial. BJU Int. 2004 93:311–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bymaster FP, Dreshfield-Ahmad LJ, and Threlkeld PG. et al. Comparative affinity of duloxetine and venlafaxine for serotonin and norepinephrine transporters in vitro and in vivo, human serotonin receptor subtypes, and other neuronal receptors. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001 25:871–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran PV, Bymaster FP, and McNamara RK. et al. Dual monoamine modulation for improved treatment of major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003 23:78–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thor KB, Katofiasc MA. Effects of duloxetine, a combined serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, on central neural control of lower urinary tract function in the chloralose-anesthetized female cat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;274:1014–1024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCall RB, Aghajanian GK. Serotonergic facilitation of facial motoneuron excitation. Brain Res. 1979;169:11–27. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90370-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrams P, Cardozo L, and Fall M. et al. The Standardisation of Terminology of Lower Urinary Tract Function: Report From the Standardisation Sub-Committee of the International Continence Society. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002 187:116–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinner NR, Dmochowski RR, and Miklos JR. et al. Duloxetine versus placebo in the treatment of stress urinary incontinence (SUI). Neurourol Urodyn. 2002 21:383–384. [Google Scholar]

- Raskin J, Goldstein DJ, and Mallinckrodt CH. et al. Duloxetine in the long-term treatment of major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003 64:1237–1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claghorn JL, Earl CQ, and Walczak DD. et al. Fluvoxamine maleate in the treatment of depression: a single-center, double-blind, placebo-controlled comparison with imipramine in outpatients. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1996 16:113–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fridman EA, Starkstein SE. Treatment of depression in patients with dementia: epidemiology, pathophysiology and treatment. CNS Drugs. 1998;14:191–201. [Google Scholar]

- Viktrup L, Bump RC. Pharmacological agents used for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence in women. Curr Med Res Opin. 2003;19:485–490. doi: 10.1185/030079903125002126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua TC, Pan A, and Chan C. et al. Effect of duloxetine on tolterodine: pharmacokinetics in healthy volunteers. Br J Clin Pharmacol. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norpramin (desipramine). Physicians' Desk Reference. Montvale, NJ: Medical Economics Company, Inc. 2002 755. [Google Scholar]

- Holm KJ, Spencer CM. Reboxetine: a review of its use in depression. CNS Drugs. 1999;12:65–83. [Google Scholar]

- Steffens DC, Krishnan KR, Helms MJ. Are SSRIs better than TCAs? comparison of SSRIs and TCAs: a meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety. 1997;6:10–18. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6394(1997)6:1<10::aid-da2>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkin RL, Lubenow TR, and Bruehl S. et al. Management of chronic pain, pt 2. Dis Mon. 1996 42:457–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auster R. Sertraline: a new antidepressant. Am Fam Physician. 1993;48:311–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benazzi F. Urinary retention with sertraline, haloperidol, and clonazepam combination [letter] Can J Psychiatry. 1998;43:1051–1052. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Central nervous system drugs in development. U S Pharmacist. 1993;18:105. [Google Scholar]

- Katofiasc MA, Nissen J, and Audia JE. et al. Comparison of the effects of serotonin selective, norepinephrine selective, and dual serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors on lower urinary tract function in cats. Life Sci. 2002 71:1227–1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benazzi F. Urinary retention with venlafaxine-fluoxetine combination. Hum Psychopharmacol. 1998;13:139–140. [Google Scholar]

- Effexor (venlafaxine). Physicians' Desk Reference. Montvale, NJ: Medical Economics Company, Inc. 2002 3503. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer CM, Wilde MI. Milnacipran: a review of its use in depression. Drugs. 1998;56:405–427. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199856030-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasper S, Pletan Y, and Solles A. et al. Comparative studies with milnacipran and tricyclic antidepressants in the treatment of patients with major depression: a summary of clinical trial results. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1996 11suppl 4. 35–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crandall C. Tolterodine: a clinical review. J Women Health Gend Based Med. 2001;10:735–743. doi: 10.1089/15246090152636488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detrol (tolterodine). Physicians' Desk Reference. Montvale, NJ: Medical Economics Company, Inc. 2002 3624. [Google Scholar]