Abstract

On March 22, 2004, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a health advisory informing the public that manufacturers of several popular antidepressants have been asked to include a warning statement on product labeling. This warning statement recommends that antidepressant-treated patients—both children and adults—should be closely monitored for worsening of depression or emergence of suicidal behavior. The full text of the advisory, along with supporting information and presentations from the February 2004 meeting on which this advisory was based, can be found on the FDA's Web site at http://www.fda.gov/cder/drug/antidepressants/default.htm.

Recently, the CME Institute, as a service to its members—you, the readers of this journal—and Larry Culpepper, M.D., Editor in Chief of the Primary Care Companion, assembled a group of psychiatrists and primary care physicians to discuss the FDA advisory and advise clinicians how it will affect their treatment of depressed patients. Their discussion and recommendations appear here.

Faculty affiliations and disclosures appear at the end of this Commentary.

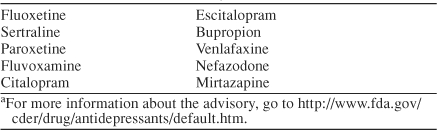

Suicide is a tragic but not uncommon outcome to psychiatric illness. The risk and rate of suicide among those who are mentally ill are higher than among the general population, and much effort has been made by researchers and clinicians in both psychiatry and primary care to find ways to prevent suicide in these patients. However, reports that antidepressant use can be associated with an increase in suicidal thoughts and behavior are cause for concern and have resulted in the public health advisory issued by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in March 2004. This advisory contained warnings relevant to 10 popular antidepressant agents (Table 1); for a summary of the warning information contained in the advisory, see Table 2.

Table 1.

Antidepressants Named in the FDA Public Health Advisorya

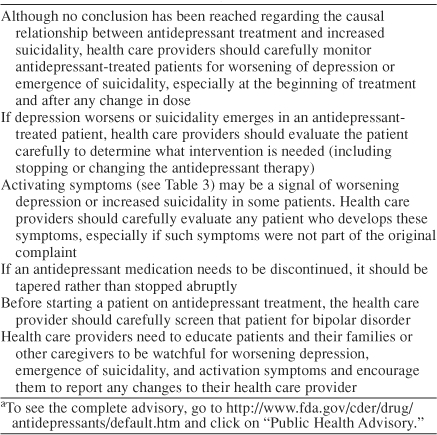

Table 2.

Summary of Warning Information From the FDA Public Health Advisorya

Issues Involved in the FDA's Assessment of ether Antidepressants Are Associated With Increased Suicidality

Dr. Culpepper: Let me begin by posing some basic questions. What are the issues involved in the FDA's assessment of whether antidepressants are associated with increased suicidality and potentially dangerous behavior? What was this advisory based on, and why was it released now?

Dr. Goodman: This investigation started with a focus on the pediatric population during the meeting of the FDA Psychopharmacologic Advisory Committee and the Pediatric Subcommittee in February 2004. We were presented with primarily unpublished data, particularly the results of 15 clinical trials of antidepressants in pediatric depression, that were submitted to the FDA. No child in those studies completed suicide. One might expect that worsening depression led to suicidal behavior and that this behavior would be more common in the placebo-treated groups, but that was not what was found. There was a stronger signal in some of the studies for suicidal behavior or suicide attempts, depending on how it was defined, in the drug-treated groups compared with the placebo-treated groups. This result was not uniform, however. In addition, in contrast to what we see with adults, particularly with the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), the demonstrated improvement compared with placebo in this pediatric population was not large. In fact, only 3 of 15 studies submitted to the FDA were considered positive. Others were either failed or negative trials.

Dr. Culpepper: In other words, there is a persistent trend that emerges from these data, although these data were not collected specifically to explore this question of suicidality.

Dr. Goodman: To put these events and findings in context, you have to remember what happened more than 10 years ago with the report from Teischer and coworkers [Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147:207–210. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.2.207. ] that raised concern about fluoxetine-induced suicidality in adults. Thereafter, careful large-scale studies examined suicidality in fluoxetine-treated patients [Leon AC. et al. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:195–201. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.2.195. ; Khan A. et al. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2001;4:113–118. doi: 10.1017/S1461145701002322. ; Storosum JG. et al. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1271–1275. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.8.1271. ], and any suspected relationship was largely debunked. The difference now is the relative strength of the pediatric data. We needed to consider these data seriously and not just harken back to the previous analyses in adults.

One result to consider is that the signal of suicidal behavior was higher in drug-treated patients than placebo-treated patients in some of the 15 studies presented. It was not a consistent effect by any means. In fact, the risk ratio was elevated in only 3 of the studies. Data from 25 pediatric studies were analyzed, comprising more than 4000 patients and including the 15 depression studies and 1 other depression study, 4 obsessive-compulsive disorder studies, 2 generalized anxiety disorder studies, 2 attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder studies, and 1 social anxiety disorder study. In all, 109 patients experienced 1 or more events that were considered “possibly suicide related.”

Dr. Culpepper: How did the FDA expand its focus from children and adolescents to include adults as well?

Dr. Goodman: The initial focus was clearly on the pediatric population. However, 63 public testimonials were also presented at the meeting. These were anecdotal reports, and the most typical ones were by bereaved parents talking about their teenaged or young adult child who had committed suicide shortly after starting antidepressant treatment. My speculation is that there was some influence from those anecdotal reports, which were not limited to children.

If you read the FDA advisory carefully, it does not establish a firm, causal connection between suicidality and these antidepressants. There is also a focus on the so-called “activation syndrome,” which may or may not be a precursor to suicidal behavior. It may be that the FDA realized that it needs to make all clinicians aware that patients in all age groups may be sensitive to these drugs in the early phase of the treatment.

Activation Syndrome

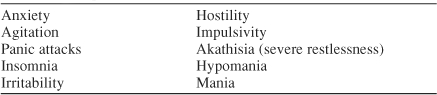

Dr. Culpepper: From both psychiatric and primary care perspectives, is the concept of an activation syndrome new, or are prior concerns being repackaged (Table 3)?

Table 3.

Symptoms of Activation Syndrome

Dr. Dietrich: Thinking back to the age before SSRIs, I remember in medical school being told that when you prescribe an antidepressant, you had to monitor the patient very carefully during the initial phases of treatment. The effects of the antidepressant would sometimes allow patients the motivation and energy to act on an impulse or desire that their depression had previously kept them from acting on. This activation syndrome seems similar but with increased specificity and a new label.

Dr. Davidson: I agree to some extent. Even before SSRIs, we were told to be careful in the first week or two of antidepressant treatment, including electroconvulsive therapy. The activation preceded the improvement of depressed mood and suicidal thoughts, so suddenly patients had the energy to carry out things that they had been somewhat inhibited from doing because of retardation or indecision.

There are a couple of factors to consider. One is that any antidepressant treatment may, in the early phases, provoke suicidal behavior, but that doesn't really answer the problem under discussion, because these reports of self-destructive behavior are not all early side effects. They seem to be scattered throughout the entire period of treatment.

A second observation is that we have definitely known for some time about what used to be called the antidepressant jitteriness syndrome. I have seen this syndrome more in patients with panic disorder or somatizing anxiety; these patients may get very agitated and then become distressed by that agitation. In my experience, they do not often become suicidal. Overall, if you see a patient with these symptoms, you have to determine if there may be complicating symptoms of panic attacks or unrecognized anxiety, or, for that matter, patients with undiagnosed bipolar disorder. These issues are of some concern in determining what is meant by activation syndrome.

Dr. Culpepper: I was perplexed about the activation syndrome because as I read the FDA's description of symptoms (see Table 3), I was reminded of an idiosyncratic reaction that I have seen in some patients—for example, an anxiety patient started on treatment with full-dose fluoxetine who comes in for a follow-up visit pacing and reporting inability to sleep. In other words, I see it as somatic activation.

Dr. Goodman: I think for the most part, the committee was talking about early side effects on the basis of clinical impressions, including the anecdotal reports of parents in which suicide seemed to be a problem in the early phases of the treatment. If this is the case, it would coincide with what Drs. Davidson and Culpepper mentioned, the need to be careful with the anxious patient and to start such a patient with a low dose, monitor carefully, and raise the dose slowly when needed.

In addition, multiple mechanisms might account for this activation syndrome or behavioral toxicity. In fact, during the 1991 committee meetings that followed Teischer and coworker's original report on fluoxetine-induced suicidality, Dr. Teicher presented a list of possible mechanisms to explain suicidality. An example is the rollback phenomenon, which is an older term that describes a patient with melancholic depression or psychomotorically retarded depression who becomes activated after treatment. However, the committee felt that this phenomenon probably occurs rarely in the pediatric population, in which few depressed children are psychomotorically retarded. Another item on this list is stage shifts from depression to mixed or manic states in patients with undiagnosed bipolar disorder.

Dr. Culpepper: Other mechanisms on that list are paradoxical worsening of depression, akathisia, and insomnia, in addition to induction of anxiety and panic attacks. The activation syndrome, then, may cover a set of behaviors that may have several different origins.

Dr. Schwenk: We are dealing with a very loosely defined and heterogeneous group of problems, many of which we have all seen for the entire time we have been working with patients. This advisory does return our focus to close follow-up and monitoring as well as making appropriate adjustments when treating depressed patients, but I am unconvinced that antidepressants regularly trigger some ominous, discrete event that spins into a high level of suicidality.

Management of Patients Already Taking Antidepressants

Dr. Culpepper: We all have patients of a variety of ages who are taking antidepressants, and many of them have probably heard the news reports about the FDA advisory and other news stories about suicide and antidepressants. The advice from the FDA is that concerned patients should call their physicians—we are the physicians in question, so what do we tell patients who are concerned about their medications?

Dr. Schwenk: Early, close follow-up has always been recommended but has not always been done as it should be. We must take these issues seriously and remember that these are powerful medications used to treat a powerful disease. However, what primary care physicians do well are substantive and detailed discussions of side effects and functioning. We need to have these discussions with our antidepressant-treated patients as often as necessary until we—doctor and patient—are both convinced that treatment is proceeding well.

Dr. Culpepper: It does seem like we have moved from a time when a new patient with depression came in weekly at the beginning of treatment to now, when we will telephone a new patient for follow-up and then see that patient in the office 3 or 4 weeks after initiating treatment, if not up to 6 or 8 weeks. Is this a wake-up call that our treatment paradigm may have gotten too slack?

Dr. Kroenke: With the older antidepressants, I think part of the reason that we might have had them return earlier was often for something other than monitoring for activation. We had to titrate the older drugs more often, and the newer ones have lulled us into thinking that one dose may fit all and, even if it does not, we usually find we need to adjust the dosage less often. Second, the older agents are toxic and possibly lethal if overdosed, so we were very cautious in following up with new patients and gave them limited amounts of the drug. The SSRIs and newer antidepressants have decreased a lot of that fear of overdose.

Dr. Dietrich: Doling the medicine out carefully was certainly much more a part of my practice with the tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) than it is with the SSRIs. I have also found that my patients are less interested in coming back for an office visit 1 or 2 weeks after starting an antidepressant. Many of these patients are managing to work in spite of the depression and are unwilling to miss work again so soon after the first office visit. Williams and colleagues conducted a national survey of primary care physicians and discovered that the average time to follow-up visit was almost a month for patients with major depression and longer than a month for patients with dysthymia and minor depression [Arch Fam Med. 1999;8:58–67. doi: 10.1001/archfami.8.1.58. ]. For whatever reason, follow-up visits occur less often than many of us would like to see.

Dr. Kroenke: One thing that confused me is that the FDA is recommending a label change for these 10 newer antidepressants (see Table 1) but not for the older agents such as the TCAs. Does this mean that the FDA considers this issue of activation irrelevant with the TCAs? Another question is how do you separate common initial side effects of an antidepressant, which many of these symptoms that we have discussed are, from an actual syndrome that precedes suicidality?

Dr. Davidson: This advisory started with data on children, and my impression is that TCAs are used infrequently in children because of some of the earlier studies showing cardiovascular risks. These agents certainly should have been included in the FDA advisory, which referred to both children and adults.

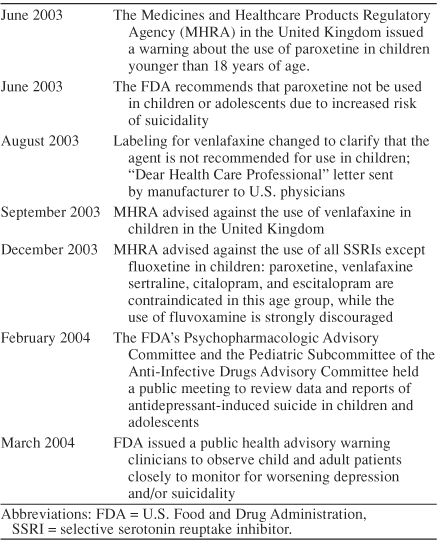

Dr. Goodman: The FDA's action in issuing the health advisory was of course preceded by the action of the British counterpart to the FDA (Table 4). The seminal event was the decision by the regulatory body in the United Kingdom to contraindicate or discourage the use of all SSRIs except fluoxetine in the pediatric population. The reason given was that few data supported the use of these agents in children, and therefore the risk-benefit ratio was unfavorable. In a sense, the decision that the FDA came to was a compromise that indicated that, on one hand, they realized there are insufficient data to establish a direct connection between these medications and suicidality, yet on the other hand, they also realized that there has been insufficient attention paid to some of the early side effects of antidepressant treatment that may or may not be precursors to suicidal behavior.

Table 4.

Timeline of Regulatory Action on Antidepressants in the United Kingdom and United States

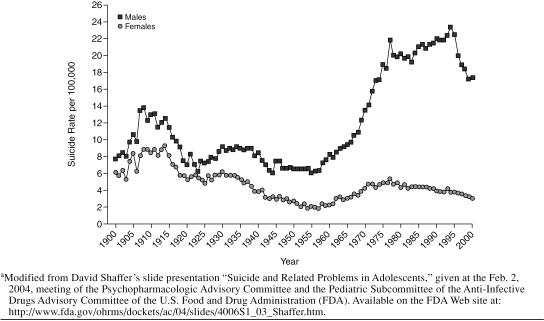

One of the presentations made at the February 2004 FDA meeting was by David Shaffer, F.R.C.P., F.R.C.Psych. He presented suicidal trend data for the adolescent population and showed very clearly a reduction in suicide from 1995 to 2000, the period in which SSRIs became the first-line treatment for depression (Figure 1). The introduction and increased use of SSRIs may not solely account for this decrease, but Dr. Shaffer was unable to exclude them as contributing to the lower suicide rate (go to http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/04/slides/4006S1_03_Shaffer.htm to view the slide presentation).

Figure 1.

Changes in Youth (aged 15–24 years) Suicide Rates in the United States During the 20th Centurya

Overall, even in the pediatric population, these drugs have done more good than harm and have saved lives. However, a cautionary note is warranted to remind physicians, patients, and family members that some patients—children in particular—have adverse behavioral reactions in the early phases of treatment. Everyone involved in the patient's care and treatment should look out for these reactions and the physician should alter the treatment as needed—adjust the dose of the medication, stop the medication, or add another medication, for example.

Dr. Culpepper: Let us narrow this down to some pragmatic advice. One of your patients who has been taking an antidepressant for some time asks you, “I've read this stuff in the newspaper; should I stop taking my antidepressant?” What do you tell him or her?

Dr. Schwenk: I would first ask the patient if he or she has been experiencing any of the side effects or symptoms that are described in the health advisory. If so, I would ask the patient to come in so that we can assess the situation. If not, reassurance is all that is necessary.

Management of Patients Who Need Treatment With an Antidepressant

Dr. Culpepper: Let us move on to discuss patients who need treatment with an antidepressant. For example, you evaluate a patient who scored a 20 on the depression section of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), which indicates severe depression, but who has never received antidepressant treatment. How do you proceed?

Dr. Kroenke: I would have a conversation with the patient that focuses specifically on suicidality, rather than a broad array of symptoms, to determine whether he or she had thoughts of death or dying and active thoughts about planning it—in other words, I would try to determine if there was risk of suicidality. I would have this discussion on the day treatment begins. The higher the risk, the more likely it would be that I would involve mental health collaboration.

Dr. Culpepper: What if, when you inquire about suicidality, the patient says, “Oh no, I would never do that. I haven't had any serious inclination that way.” Do you simply start medication treatment? Do you now, since the advisory, want to get a written consent before starting medication? What do you tell the patient about the FDA advisory?

Dr. Dietrich: If I am satisfied that the suicide assessment is negative and that the patient has neither passive nor active thoughts of death at this time, I would next go into the business of patient preferences—whether the patient prefers a counseling approach or a medication approach. Assuming that the patient prefers medication either alone or in addition to counseling, I would review side effects, as usual, but now I would call the patient's attention to the recent FDA warning and tell him or her what symptoms to watch out for. I would inform the patient that, for this reason, I will be monitoring his or her response to medication closely, and I would also ask the patient to touch base with me the following week.

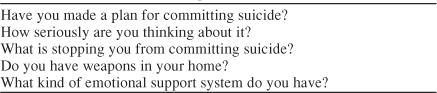

Managing Antidepressant-Treated Patients Who Report Increased Suicidality

Dr. Culpepper: From a psychiatrist's perspective, how would you now handle referrals from primary care physicians of depressed patients who have become suicidal? For example, let us say that I have a patient who one day remarks to me that she has been thinking about suicide, that one of her aunts committed suicide by overdosing on pills, and that that option is looking appealing to her. I refer her for psychiatric consultation. What are you going to do as my psychiatric consultant for this patient? In particular, how might you deal with her differently now after the FDA advisory?

Dr. Davidson: First, I would be sure to do a careful evaluation of suicide risk (Table 5). If there appears to be a fairly serious risk, I would consider hospitalizing the patient or at the very least entering into a contract with her in which she promises not to commit suicide and to call me or another person if and when serious thoughts about it cross her mind. If the risk does not seem acute, then I would tell her that she needs immediate treatment. The more suicidal the patient is, the more compelling the case for prescribing a medication as opposed to counseling, in my opinion. I would talk about the medications with her and say, “You probably have heard about the concerns in the media and from the FDA about whether these drugs can make you more suicidal, and in my judgment, it is unlikely to happen.” I would reassure her that it is more likely that she will improve with antidepressant treatment, but that we would need to stay in close contact, especially during the first few weeks of treatment. I would also involve a spouse, family member, or close friend in her care to make sure someone is always available as support.

Table 5.

Questions to Ask Depressed Patients Who Express Suicidal Thoughts

Dr. Culpepper: What if the patient is a 16-year-old boy with some symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder and other anxiety in addition to the suicidal thoughts?

Dr. Goodman: Dr. Davidson's answer was comprehensive, but I would add that with a patient with anxiety, it may be wise to start at a lower dosage than you normally would in depression without a concomitant anxiety disorder. I would also warn patients like this that they might feel a little bit anxious or jittery when they first start the medication and that they should call me if they feel uncomfortable. This is assuming that I have come to some sort of agreement with them, as Dr. Davidson recommended, and that they can be maintained on an outpatient basis.

With an adolescent, we also need to realize that the efficacy of these agents may be different. The thrust of the regulatory action in the United Kingdom, after all, was that the data demonstrating the efficacy of the SSRIs (except fluoxetine) in younger patients were weak or nonexistent. It was that lack of evidence that made the risk-benefit ratio weighted more on the risk side, given the signals of suicidal behavior in this age group. A recent article reviewed those data, published and unpublished, in more detail [Whittington CJ. et al. Lancet. 2004;363:1341–1345. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16043-1. ].

When treating adolescents, it is also important to remember that they may not be as effective as adults in verbalizing their experiences. They may feel uncomfortable or anxious but unable to describe those sensations adequately. I think you need to go out of your way with adolescents to urge them to contact you early in the stages of treatment—even before their next office visit—if they feel worse in any way, and then it will be your job to determine whether those feelings indicate worsening depression or are side effects of the medication. My suspicion is that some young adults and children have considered or even committed suicide because they did not have a way of understanding that what had happened to them was a result of negative effects of the drug. Perhaps if we can share more information with young patients to help them recognize that unpleasant sensations and feelings might be medication side effects, then we can help prevent this tragic outcome. We all—psychiatrists and primary care physicians alike—must be careful in the early phases of treatment, particularly when treating children and adolescents.

Managing Antidepressant-Treated Patients Who Report Activation Syndrome

Dr. Culpepper: What about patients who report not overt suicidality but symptoms of activation syndrome? For example, what course of action do you take with a patient who has been taking an antidepressant for 2 weeks and who calls you to report feeling unbearably on edge and irritable?

Dr. Schwenk: Assess suicidality and make a decision on that basis. If the patient has been on treatment for only 2 weeks, I would probably tell him or her to stop taking the medication and see me as soon as possible.

Dr. Culpepper: Would anybody taper medication? Dr. Goodman: It might be only necessary to lower the dose. That is an individual decision, whether to stop treatment or taper the dose. You should not increase the dose at that point.

It seems somewhat analogous to the situation of differentiating akathisia from worsening of psychosis—you cannot assume that the symptoms represent a worsening of the underlying condition without first testing to see if they are due to the medication. You conduct this test by stopping the medication, adding an adjunctive agent, or lowering the dose of the original medication.

Dr. Culpepper: In the primary care setting, how do we differentiate this activation syndrome in an antidepressant-treated patient from undiagnosed bipolar disorder? Symptoms of activation syndrome seem similar to those of antidepressant-induced mania or rapid cycling. Is that a diagnostic issue that we can deal with in primary care?

Dr. Schwenk: A key point here is that primary care physicians like myself must become more expert in the diagnosis and treatment of patients with bipolar disorder, which has become much more prevalent in our practice than it used to be. In the past, most patients with bipolar disorder were referred to a mental health specialist, but now, for a variety of reasons, many are being treated by primary care physicians. I try to be much more attentive to these symptoms of agitation, irritability, and hypomania than in the past.

Dr. Dietrich: When I initiate treatment with an antidepressant, I try to gather a careful history in terms of both the patient's own previous episodes that might have been hypomanic and family history. I warn at-risk patients to be watchful for these symptoms, and when I see a patient who appears to be switching into a manic episode, I have the luxury of getting a quick psychiatry consultation that many primary care physicians may not have. I can easily get help from one of my psychiatry colleagues in sorting out whether a patient may be on the verge of a bipolar episode.

Dr. Culpepper: What about the primary care physician who has few if any opportunity for psychiatry consultations, for example, a doctor who works in a rural area and may be a hundred miles from the nearest psychiatrist? What are other possibilities for managing a patient who is experiencing activation symptoms? Would you ever think about prescribing atypical antipsychotics to this type of patient?

Dr. Schwenk: Absolutely. We as primary care physicians have to be much smarter about using mood stabilizers and atypical antipsychotics and not be as averse to using them as we have historically been.

Dr. Culpepper: Would you consider ordering a toxicology screen in this type of patient? I have seen patients with increased irritability and agitation who denied using alcohol or illegal drugs, but their toxicology results were positive for cocaine, which of course can explain those symptoms. Has anyone else had that experience?

Dr. Davidson: In many of the clinical scenarios we have discussed, we need to make sure that the patient is avoiding alcohol and illegal drugs. I have certainly seen patients who have appeared to be irritable and impulsive and then discovered that they have mixed alcohol with their medication. We should always inquire about alcohol and drug use.

Dr. Culpepper: Earlier in the discussion, we touched on contracting for safety. Does the FDA advisory about activation and suicidality alter your perspective on the effectiveness of contracting for safety?

Dr. Schwenk: I believe that contracting is something that primary care physicians have been taught to have some faith in, but my sense is that psychiatrists may not agree with its importance.

Dr. Culpepper: I have been unable to pinpoint any scientific evidence that said that contracting works or does not work. Is it something that is unique to primary care, as Dr. Schwenk suggests?

Dr. Goodman: I have some hesitations about contracting. If you accept the possibility that in some individuals, by whatever mechanism, these medications can induce a state change, then you have to wonder how good a safety contract with one of those individuals will be. In that situation, you will not be dealing with a patient in the same state as when you wrote the contract with him or her. We should try to discuss the patient's state of mind with an informant—a spouse, close friend, or, in the case of a child or adolescent, a parent. Certainly in the case of an adolescent, if you are able to get information from a parent that the patient has been acting strangely, more hostile, or more irritable since the medication was started, that would be very useful.

Dr. Davidson: It is important to involve a significant other to determine if there have been changes in behavior, especially if these informants are educated about the illness and asked to watch out for certain types of changes.

Concluding Thoughts

Dr. Davidson: One point that we need to make is the fact that there are good trials in children and adolescents with anxiety disorders—obsessive-compulsive disorder, social phobia, and generalized anxiety disorder—that have reported a positive signal in favor of the efficacy of the newer antidepressants. There is virtually no evidence from the available database that the incidents mentioned in the FDA advisory have taken place in the anxiety population. We need to keep this very much in mind because we are obligated to help our teenaged patients who develop anxiety disorders.

Dr. Kroenke: I am concerned about generalizing study results and treatment strategies regarding children to adults and vice versa. For example, it may be easier to involve an informant with a young patient whose parents are involved in every level of treatment. With an adult patient, however, you often see the patient as an adult alone. The logistics of trying to contact a family member to participate in treatment and negotiate the privacy issues can be challenging.

Dr. Culpepper: Those are both good points. When I think about suicidality, I am reminded of the Institute of Medicine's report on preventing suicide [http://www.iom.edu/report.asp?id=3843]. One of the points in that report is that depression is often in the background of suicidal behavior, but that anxiety is often there as well. Two other critical ingredients that heighten the risk of suicide are impulsivity and substance abuse, which become quite lethal when combined. How can clinicians quickly and efficiently evaluate impulsivity?

Dr. Dietrich: With patients whom I have been treating for years and see fairly often, I have an intuitive sense of their baseline level of impulsive behavior and can detect changes. The challenge comes with a new patient who may evoke some concern in this area. In that case, I would ask many of the same assessment questions that Dr. Davidson suggested (see Table 5), about emotional support systems, use of drugs or alcohol, and availability of firearms and other means of harming oneself. I would also ask that patient about his or her decision-making process to determine if the patient tends to make snap decisions. When treating somebody new, I try to be careful about understanding those issues and where they fit into the patient's life and try to explore them in a nonjudgmental way.

In some situations, even with patients I think I know well, I will ask directly about impulsivity. Patients have surprised me with their answers, especially those whom I see as nonimpulsive but who see themselves as impulsive or report times in their life when they have been impulsive.

Dr. Culpepper: Is impulsivity a steady state or is it likely to change greatly in patients?

Dr. Davidson: It can change and, in my experience, SSRIs do alter impulsivity. They tend to control it rather than loosen it. However, we need to ask patients not only about suicidal impulses but aggressive impulses in general, and we need to monitor patients closely to determine how antidepressant treatment changes impulsivity in each individual.

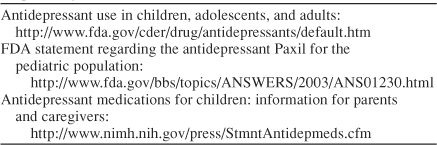

Dr. Culpepper: We as physicians must of course avoid doing harm to our patients with the treatments we prescribe. However, we must balance that with the possibility of inflicting harm by withholding possibly beneficial or lifesaving medications. The points we have emphasized here are neither new nor ominous, but reflect good clinical practice: begin antidepressant treatment carefully, monitor patients closely, and watch for signs of untoward side effects, worsening symptoms, and increased suicidality. More information about the FDA advisory and regulatory action in the United States can be found at the Web sites listed in Table 6.

Table 6.

Web Sites With Information About the U.S. Regulatory Actions on Antidepressants

Drug names: bupropion (Wellbutrin and others), citalopram (Celexa), escitalopram (Lexapro), fluoxetine (Prozac and others), mirtazapine (Remeron and others), nefazodone (Serzone and others), paroxetine (Paxil), sertraline (Zoloft), venlafaxine (Effexor).

Pretest and Objectives

Instructions and Posttest

Registration and Evaluation

Footnotes

In the spirit of full disclosure and in compliance with all ACCME Essential Areas and Policies, the faculty for this CME activity were asked to complete a full disclosure statement. The information received is as follows: Dr. Culpepper is a consultant for Cephalon, Forest, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Somerset, and Wyeth. Dr. Davidson has received speaker fees from Solvay, Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, Wyeth, American Psychiatric Association, Forest, and Eli Lilly; is a scientific advisor for Solvay, Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, Forest, Eli Lilly, Ancile, Roche, Novartis, Organon, Boehringer Ingelheim, UCB Pharma, Pharmacia, Johnson & Johnson, Boots, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cephalon, Nutrition 21, and Sanofi-Synthelabo; has received research support from Pfizer, Solvay, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Wyeth, Organon, Forest, PureWorld, Allergan, Nutrition 21, Bristol-Myers Squibb, UCB Pharma, and Cephalon; has had drug supplied for NIH and other studies by Eli Lilly, Schwabe Pharmaceutical, PureWorld, and Pfizer; and has received royalties from MultiHealth Systems, Guilford Publications, American Psychiatric Association, and Penguin Putnam. Dr. Dietrich is on the speakers/advisory boards for Forest, Pifzer, and Wyeth. Dr. Goodman is an employee of the University of Florida Department of Psychiatry; has received grant/research support from Eli Lilly, Forest, GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, and Wyeth; and is a consultant/speaker for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Forest, Janssen, Pfizer, Roche, and Solvay. Dr. Kroenke has received grant/ research support from Eli Lilly and Wyeth, has received honoraria from Pfizer, and is on the speakers/advisory board for Eli Lilly. Dr. Schwenk is a consultant for Eli Lilly.