Abstract

This Academic Highlights section of The Primary Care Companion to The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry presents the highlights of the planning roundtable “Effective Recognition and Treatment of Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) in the Primary Care Setting,” held December 11, 2003, in Pittsburgh, Pa. The planning roundtable and this Academic Highlights were supported by an unrestricted educational grant from Pfizer.

The planning roundtable was chaired by Larry Culpepper, M.D., M.P.H., Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Mass. The faculty member was Kathryn M. Connor, M.D., Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C.

Anxiety Disorders in the Primary Care Setting

Larry Culpepper, M.D., M.P.H., began the presentation by stating that more than 26 million people aged 15 to 54 years in the United States suffer from anxiety disorders, either alone or comorbid with at least 1 other psychiatric disorder.1 Anxiety disorders cost billions of dollars in the United States each year.2 This cost reflects not only the direct cost of treatment but also indirect costs such as missed days from work.2 Patients with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and depression are frequently described as high health care utilizers, with numerous visits to their primary care physician.3

Data1,4 indicate that the majority of psychiatric disorders in the United States are treated in the primary care setting. Dr. Culpepper discussed the need for awareness among primary care physicians about the prevalence and types of anxiety disorders, focusing on GAD, as well as management strategies.

Origins of Worry and Anxiety

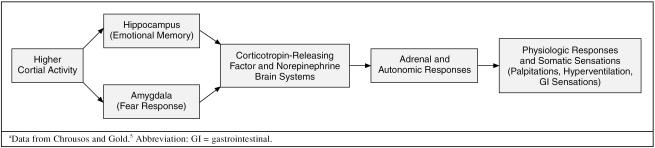

Dr. Culpepper explained that anxiety expresses itself neurologically through higher cortical activity. For example, this activity can be activated by sudden noises or memories. Higher cortical activity, in turn, stimulates other portions of the brain resulting in physiologic responses and consequent somatic sensations (Figure 1).5

Figure 1.

Origins of Worries and Anxiety: Fight or Flight Responsea

The somatic sensations are what drive many patients into primary care offices: heart palpitations, hyperventilation, gastrointestinal problems, or other types of discomfort. Anxiety disorders usually emerge when patients are in their 20s and early 30s; however, anxiety disorders originate much earlier in life, with most anxiety developing during childhood and adolescence. Genetic background and early upbringing are 2 predictors of anxiety disorders. Twenty percent to 30% of patients with panic or GAD have relatives with the same disorder, and thus patients with a family background of anxiety are more likely to develop an anxiety disorder than patients without a family background of anxiety.6,7 Early adverse experiences can lead to an expression of a preexisting genetic vulnerability to stress and disease. Studies8,9 indicate that children raised in unpredictable environments with neglect, separation, or abuse are more likely to develop anxiety disorders than children raised in stable environments.

The Need for Recognition of Anxiety Disorders in the Primary Care Setting

Anxiety is often a chronic condition that can impair patients' daily functioning and lead to secondary comorbid conditions. The severity of physical and psychosocial impairment can lead to decreased work productivity, missed days from work, and even unemployment.10,11 Fifer et al.12 reported that 10% of patients screened in clinic waiting rooms suffered from unrecognized or untreated anxiety. These patients reported substantially worse functioning on both physical and emotional measures than patients who reported that they were not anxious. Maki et al.11 found that primary care patients with GAD demonstrated more severe to comparable physical and psychosocial impairment compared with subjects who were diagnosed with severe medical conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, and recent myocardial infarction.

Dr. Culpepper emphasized that recognizing an anxiety disorder can be difficult for physicians. Patients with anxiety disorders, such as GAD, frequently turn to their primary care physician when they have exhausted their coping skills and are suffering from concerns about potential illness, pain, or other physical maladies. Often, patients are unaware that their physical maladies are associated with the presence of an underlying anxiety disorder.13 Patients usually attribute anxiety-like symptoms to 1 of 3 causes: somatic complaints, psychological complaints, or normalizing complaints. Patients who present their symptoms as psychological complaints, e.g., emotional exhaustion, have been found to be more likely to receive a psychiatric diagnosis than patients whose symptom attribution is normalizing (e.g., my problems are caused by work-related stress) or somatizing.14

Anxiety Comorbid With Other Disorders

Physicians need to be aware of the risk of comorbid conditions in patients with anxiety disorders. Anxiety disorders tend to be highly comorbid, and patients frequently suffer from multiple anxiety disorders. For example, in an ongoing longitudinal naturalistic study15 of anxiety disorders in the primary care setting, 36% of patients with GAD had 1 other anxiety disorder, 14% had 2 others, and 4% had 3 others. Forty-one percent of the subjects with anxiety had comorbid major depression.

Anxiety disorders are the most common disorder associated with major depressive disorder. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey16 found that 58% of respondents who had a lifetime prevalence of major depressive disorder suffered from an anxiety disorder as well. In general, major depression comorbid with another disorder is more persistent and severe than primary depression.16

Dr. Culpepper noted that patients with anxiety and comorbid depression experience more impairment in quality of life than those with either disorder.17 The combination of anxiety and depression not only is more difficult to treat but also places the patient at risk for more serious complications. Patients often attempt to self-medicate; alcohol dependence and substance abuse are commonly seen in patients with anxiety disorders. Comorbid depression may also place patients with anxiety disorders at a higher risk for suicide attempts.11

Recognizing Patients With GAD

The DSM-IV18 classifies GAD as excessive worry and anxiety, occurring for more days than not for at least 6 months. GAD is a waxing and waning disorder, and patients will often have periods of moderate anxiety combined with periods of acute exacerbation that may last for days or weeks.19 Physicians may see patients during phases of acute exacerbation when patients have exhausted their coping skills.

Patients with GAD often present with somatic complaints, such as motor tension or hyperarousal. The hallmark of GAD is that patients are having difficulty controlling pervasive worry, i.e, their worry is out of proportion to the likelihood or impact of the dreaded events.

One study20 examined the relationship between physical symptoms and psychiatric symptoms reported by 1000 patients in the primary care setting. Somatic symptoms were determined to be potential markers for an anxiety disorder. Although insomnia, chest pain, and abdominal pain were the most common somatic symptoms reported, followed closely by headache and fatigue, researchers determined that the number of symptoms, rather than the type of symptom, was the strongest indicator of a mood or anxiety disorder.

Dr. Culpepper stated that it is important to realize that patients with GAD often have a range of somatic complaints, but they frequently see their physician about one particular symptom that is bothering them at the time. Usually patients are most concerned with this one symptom and frequently view other symptoms as a normal part of their overall functioning. Physicians need to ask patients about other potential symptoms in order to more effectively diagnose an anxiety disorder.

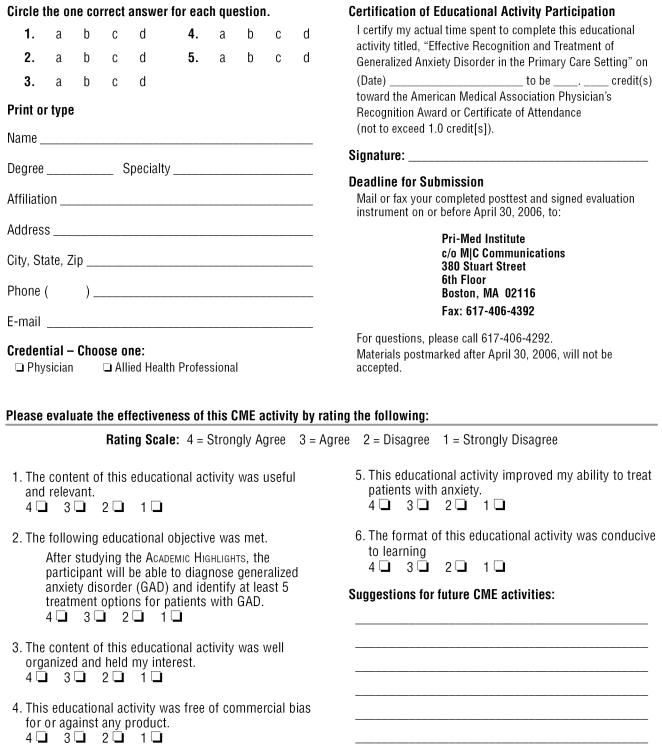

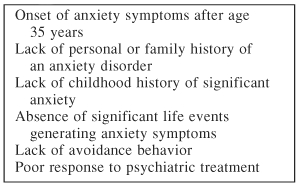

Although a number of medical conditions can mimic anxiety, these conditions are usually self-evident. For example, patients who have begun a new medication and begin to report anxiety-like symptoms may be suffering from an idiosyncratic reaction to their medication. By knowing the features of anxiety secondary to organic causes, physicians can rule out non-anxiety disorder problems (Table 1). Differential diagnosis involves ruling out medical illness and iatrogenic causes (Table 2).

Table 1.

Features of Anxiety Secondary to Organic Causes

Table 2.

Differential Diagnosis: Anxiety Secondary to Organic Factors

Relapse and Recovery

Although patients may recover from anxiety disorders without treatment, the risk of relapse has been found to be greater in untreated patients. In a study21 of the probability of recovery, relapse, and recurrence in a 3-year course of anxiety disorders, 40% of patients with GAD achieved remission of symptoms after a 3-year period, but the probability of relapse or recurrence of symptoms was found to be near 30% among those that did remit.

Patients with anxiety disorders need to receive treatment in order to alleviate and prevent the recurrence of symptoms.

Management of Anxiety Disorders

Patients with anxiety disorders are often hesitant to try medication due to the stigma and embarrassment they associate with treatment. Patients who appear unwilling to try medication should be reminded that anxiety disorders involve their brain neurochemistry and that treatment may improve that condition. Patients should be encouraged to view their disorder as a disease.

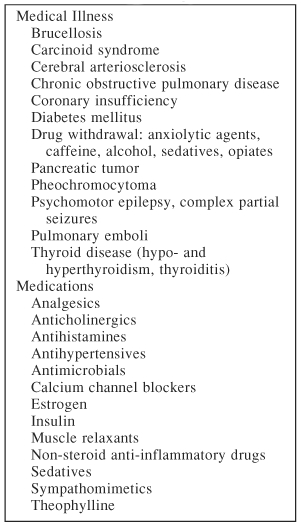

It is also important for physicians to continuously encourage patients to maintain treatment compliance. Lin et al.22 found that patients who received specific educational messages (Table 3) were more likely to comply with treatment during the first month of antidepressant therapy than patients who did not receive any instructions.

Table 3.

Types of Educational Messages Physician May Use to Improve Patient Compliancea

Psychotherapy may be another effective treatment for anxiety disorders. Types of psychotherapy include cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), insight-oriented therapy, and family or group therapy. CBT works through reeducating patients to correct misconceptions, to modify unconscious mental representations of events, and to modify self-regulation of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors.

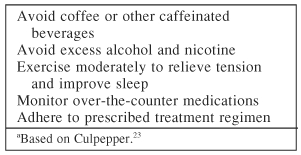

Patients with anxiety tend to not associate their behavior with an increase in their stress and anxiety levels. Physicians should provide patients with general recommendations (Table 4) that may aid in managing anxiety.

Table 4.

General Recommendations for Patients With Anxiety Disordersa

Conclusion

Anxiety disorders are often persistent conditions that impair patients' daily functioning. Anxiety disorders are highly prevalent in primary care settings and are often reported in terms of somatic complaints. Anxiety disorders are also highly comorbid with each other and depression, which leads to an increased medical utilization and worse outcomes than patients with anxiety or depression alone. GAD often develops early in life and proceeds into major depression.

Recognizing an anxiety disorder may be difficult; however, physicians can make a diagnosis of an anxiety disorder through an active search of symptoms in their patients, keeping in mind that the patient may have comorbid psychiatric and/or medical conditions as well. Physicians can help patients to manage their anxiety through education and encouragement to adhere to prescribed treatments.

REFERENCES

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, and Zhao S. et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994 51:8–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg PE, Sisitsky T, and Kessler RC. et al. The economic burden of anxiety disorders in the 1990s. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999 60:427–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon W, Von Korff M, and Lin E. et al. Distressed high utilizers of medical care: DSM-III-R diagnosis and treatment needs. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1990 12:355–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisberg RB. Management of anxiety disorders in primary care: implications for psychiatrists. In: Syllabus and Proceedings Summary of the 156th Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association. 17–22May2003 San Francisco, Calif. Abstract 24C:278. [Google Scholar]

- Chrousos GP, Gold PW. The concepts of stress and stress system disorders: overview of physical and behavioral homeostasis. JAMA. 1992;267:1244–1252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe RR. The genetics of panic disorder and agoraphobia. Psychiatr Dev. 1985;3:171–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genetics and Mental Disorders: Report of the NIMH's Genetics Workgroup. National Institute of Mental Health 1998. Available at http://www.nimh.nih.gov/publist/984268.htm. Accessed Jan 20, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Heim C, Nemeroff CB. The role of childhood trauma in the neurobiology of mood and anxiety disorders: preclinical and clinical studies. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49:12023–12039. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01157-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan GM, Kent JM, and Coplan JD. et al. The neurobiology of stress and anxiety. In: Mostofsky DI, Barlow DH, eds. The Management of Stress and Anxiety in Medical Disorders. Boston, Mass: Allyn and Bacon. 2000 15–35. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce S, Rodriguez BF, and Weisberg RB. et al. Occupational impairment of primary care patients with social anxiety disorder. In: New Abstracts of the 156th Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association. 22May2003 San Francisco, Calif. Abstract NR779:291. [Google Scholar]

- Maki K, Weisberg RB, and Keller MB. et al. Psychosocial and work impairment in primary care patients with GAD. In: New Research Abstracts of the 156th Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association. 19May2003 San Francisco, Calif. Abstract NR9:4. [Google Scholar]

- Fifer SK, Mathias SD, and Patrick BL. et al. Untreated anxiety among adult primary care patients in a health maintenance organization. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994 51:740–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen HU, Kessler RC, and Beesdo K. et al. Generalized anxiety and depression in primary care: prevalence, recognition, and management. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002 63suppl 8. 24–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler D, Lloyd K, and Lewis G. et al. Cross sectional study of symptoms attribution and recognition of depression and anxiety in primary care. BMJ. 1999 318:436–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez BF, Weisberg RB, and Pagano ME. et al. Frequency and patterns of psychiatric comorbidity in a sample of primary care patients with anxiety disorders. Compr Psychiatry. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Nelson CB, and McGongale KD. et al. Comorbidity of DSM-III-R major depressive disorder in the general population: results from the U S National Comorbidity Survey. Br J Psychiatry. 1996 168suppl 30. 17–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisberg RR, Keller MB, and Allsworth JE. et al. Functioning and well-being of primary care patients with anxiety disorders. Presented at the 154th Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association. 13–18May2000 Chicago, Ill. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Revised. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. 1994 [Google Scholar]

- Rickels K, Schweizer E. The clinical presentation of generalized anxiety in primary care settings: practical concepts of classification and management. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997 58suppl 11. 4–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, and Williams JBW. et al. Physical symptoms in primary care: predictors of psychiatric disorders and functional impairment. Arch Fam Med. 1994 3:774–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez BF. Characteristics and clinical course of GAD in primary care patients [poster]. Presented at the 23rd Annual Meeting of the Anxiety Disorders Association of America. March2003 Toronto, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Lin EH, Von Korff M, and Katon W. et al. The role of the primary care physician in patients' adherence to antidepressant therapy. Med Care. 1995 33:67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culpepper L. Worries and anxiety. In: DeGruy FV, Dickinson WP, Staton AW, eds. 20 Common Problems in Behavioral Health. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Medical Publishing Division. 2002 385–404. [Google Scholar]

Treatment of Generalized Anxiety Disorder: Current Options and Future Developments

Kathryn M. Connor, M.D., stated that GAD is the most prevalent anxiety disorder seen in the primary care setting.1 Since GAD patients are more likely to see their primary care physician than a psychiatrist, primary care physicians need to be aware of the benefits and drawbacks of current GAD treatments. Current medication options include benzodiazepines, buspirone, tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and venlafaxine, among others. Research on other potential treatments for GAD is also underway.

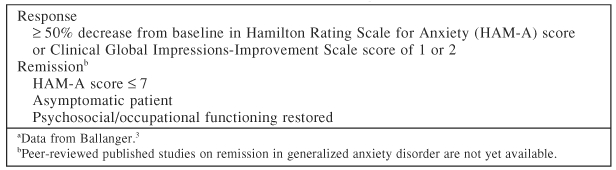

Treatment Goals for GAD

Response to treatment is a good start, but remission is the ultimate treatment goal for GAD (Table 5). For patients to achieve remission, physicians must find treatments that are effective in treating both the psychic and somatic symptoms of GAD. When treating patients with anxiety disorders, physicians need to consider treatment options that have a rapid onset of action, while minimizing adverse effects. Side effects can be particularly challenging in patients with GAD, since patients with anxiety tend to be more sensitive to medication side effects than other patient populations, said Dr. Connor. Also, since GAD is a chronic condition, physicians should consider prescribing medications that have a limited potential for abuse and are suitable for long-term treatment.

Table 5.

Goals of Treatment in Generalized Anxiety Disordera

Noncompliance and treatment costs can hinder a patient's recovery. By selecting medications that require once-a-day dosing, physicians may be able to improve compliance. Many medications used in the treatment of GAD are now available in generic formulations, which may ease patients' financial burden associated with treatment.

Benzodiazepines

Benzodiazepines were one of the earliest approved treatments for anxiety disorders and have been prescribed to patients steadily over the past 40 years. In the 1960s, benzodiazepines replaced barbiturates as the pharmacologic gold standard for anxiety treatment. Benzodiazepines potentiate the inhibitory effects of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) at the GABAA receptor, a major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system.

Benzodiazepines have a rapid onset of symptom relief; most improvement occurs within the first few weeks of treatment. In trials comparing benzodiazepines with placebo, 65% to 75% of patients achieved moderate-to-marked improvement with benzodiazepines.2

Although response to benzodiazepine treatment is usually seen at the beginning of treatment, benzodiazepines may lose effectiveness during long-term treatment. Therefore, physicians may need to increase dosage during long-term treatment to maintain efficacy.

One drawback of benzodiazepines is that they do not prevent depression and in some cases may precipitate or exacerbate it. Other potential side effects of benzodiazepines include sedation, fatigue, impaired psychomotor performance, decreased learning ability, synergistic effects with alcohol, and sleep disturbances. Many physicians and patients are concerned about the potential for patients to become dependent on benzodiazepine treatment. However, while the potential to develop physiologic and psychological dependence with benzodiazepine treatment does exist, few patients actually develop a dependence on benzodiazepines.

Dr. Connor noted that, when discontinuing benzodiazepine treatment, patients are at risk for developing rebound anxiety and withdrawal symptoms. Rebound anxiety may develop after the first week of discontinuation and may last for up to 6 weeks. Rebound or withdrawal symptoms may occur in patients who have been treated for as few as 3 weeks. However, patients can be safely discontinued from benzodiazepine treatment. Physicians should slowly taper medication over several weeks to months in order to minimize potential risks.

Alprazolam, a short-acting benzodiazepine, has recently been released in an extended-release formulation, while clonazepam is now available in a quickly dissolving wafer formulation. Many benzodiazepine treatments are also available in generic formulations, which allows for low cost to patients.

Buspirone

Buspirone was the first nonbenzodiazepine anxiolytic approved for the treatment of GAD, in 1986. Buspirone is a serotonin-1A (5-HT1A) partial agonist, which is mechanistically different from other anxiolytics. Studies4,5 have found buspirone to be superior to placebo in the treatment of GAD and mild depressive symptoms. Buspirone has recently become available in generic formulations.

Buspirone, unlike benzodiazepines, is not associated with physiologic dependance, tolerance issues, withdrawal symptoms, or alcohol interactions. Buspirone tends to be better tolerated than benzodiazepines because it lacks the same degree of psychomotor and cognitive impairment. However, patients who respond well to benzodiazepines do not seem to respond as well to buspirone. This lack of response may in part be due to buspirone's lack of efficacy for somatic symptoms.

Buspirone does not work as quickly as benzodiazepines, and the half-life is relatively short. Because of this short half-life, patients prescribed buspirone will often need a t.i.d. dosing regimen.

Tricyclic Antidepressants

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are one of the oldest classes of antidepressants and the first class of antidepressant medications to be studied in the treatment of GAD. TCAs work through the inhibition of serotonin and/or norepinephrine reuptake. TCAs have been found to be effective not only as antidepressant treatments but also as antianxiety agents.

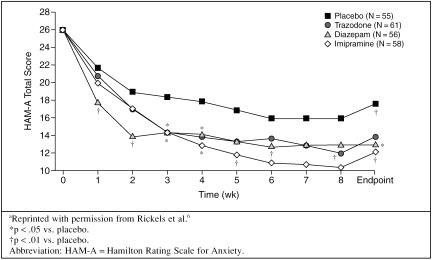

Rickels and coworkers6 conducted an 8-week placebo-controlled study comparing the benzodiazepine diazepam, the TCA imipramine, and the heterocyclic antidepressant trazodone. Patients treated with diazepam showed an early response that plateaued after week 2. The antidepressants demonstrated a slower but steady rate of improvement, and all active treatments were found to have similar efficacy at endpoint (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Antidepressants and Benzodiazepines in Generalized Anxiety Disordera

Dr. Connor cautioned that TCAs can be associated with a number of side effects, such as anticholinergic effects (dry mouth, urinary retention), orthostatic hypotension, sedation, and weight gain. These side effects can be troublesome to patients and may lead to medication noncompliance. TCAs have also been associated with cardiac conduction abnormalities, and patients prescribed long-term treatment with TCAs need to have regular electrocardiogram (ECG) and blood level monitoring to avoid toxicity. Physicians should be aware that TCAs have been found to be lethal in overdose and should use caution when prescribing TCAs to patients with suicidal tendencies.

Heterocyclic Antidepressants

Heterocyclic antidepressants are similar in action on the brain to TCAs and have been found to be effective in treating depression with less risk of overdose than TCAs.7 Heterocyclic antidepressants have demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of acute GAD,6 but these drugs have not received FDA approval for this indication.

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors

SSRIs are currently the most widely prescribed treatment for anxiety disorders and are considered a first-line treatment. SSRIs are known to be effective antidepressant agents and are also approved for a variety of anxiety indications. For many patients, however, the cost of these medications is prohibitive, which limits their utility, but some are available in generic formulations.

In anxiety disorders, one of the more widely studied SSRIs is paroxetine. Paroxetine has shown efficacy in both short-term and long-term treatment of GAD.8 Sertraline9 and escitalopram10 have also demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of GAD.

SSRIs, like TCAs, have a slower time to onset compared with benzodiazepines. Patients may become frustrated by the lack of immediate efficacy, and physicians may need to encourage patients to stay compliant with their medication.

While SSRIs have a lower risk of cardiovascular side effects than TCAs, bothersome side effects may occur that can limit patient compliance. Two significant side effects that physicians have begun to appreciate in recent years are sexual dysfunction and weight gain. Physicians should make patients aware of the potential for these side effects before prescribing an SSRI. Physicians and patients do have options in managing these side effects, and physicians need to encourage patients to stay compliant with their medication and report any problems.

One strategy to minimize potential side effects is to begin patients at a lower-than-recommended dose and slowly titrate upward. For example, physicians may want to begin paroxetine treatment at 5 or 10 mg/day for a week or more to minimize the risk of side effects. While this dosage is lower than what is generally prescribed to patients treated for depression, starting at a lower dosage may increase patient compliance and limit the potential for adverse effects.

Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors

Venlafaxine-XR is currently the only serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) approved for the treatment of GAD and major depression in the United States. SNRIs bind with high affinity to serotonin and norepinephrine transporters and inhibit the pre-synaptic reuptake of these neurotransmitters.

Venlafaxine has been found to be effective in short- and long-term treatment of GAD, with or without comorbid major depression.11,12 A placebo-controlled study11 showed significant improvement with venlafaxine as early as the first week of treatment; however, the most significant effects were seen at the end of an 8-week period, when patients were treated with higher doses of venlafaxine (150 to 225 mg/day).

Treatment Strategies

Dr. Connor noted that patients with comorbid depression and anxiety are often more difficult to treat than patients with anxiety alone. These patients often benefit from antidepressant treatment, and physicians may want to consider beginning these patients on a combination of a benzodiazepine and an antidepressant in order to relieve anxiety quickly and to minimize the lag effect often seen with antidepressant treatment alone. As patients improve, physicians may then consider discontinuing the benzodiazepine. Adding a benzodiazepine or other anxiolytic agent may also be effective in treating patients who are not responding well to antidepressant monotherapy.

Many patients with anxiety often have poor anxiety management skills. Adding adjunctive psychotherapy to their treatment may be beneficial. In a 6-month follow-up of patients with GAD who received CBT, 51% of patients demonstrated improved recovery rates, compared to only 4% receiving psychoanalytically oriented therapy.13

Once patients achieve remission, there is often a strong tendency to discontinue treatment. However, patients who discontinue treatment early are at great risk for relapse and recurrence of symptoms. Physicians should discourage patients from discontinuing their medication unadvised. In general, a patient who has responded to pharmacotherapy should be stable for about a year before considering medication taper and discontinuation. At that time, if the patient continues to do well and has a stable psychosocial situation, the clinician could gradually taper the patient's dose of medication over the next several months.

Future Treatments

While several pharmacologic options are currently available for the treatment of GAD, these treatments are not effective for every patient. Research into new treatments for GAD has focused on other neurochemicals with novel mechanisms of pharmacologic action, as well as new compounds with mechanisms similar to current medication, but with enhanced efficacy and tolerability profiles.

Duloxetine.

Duloxetine, an SNRI, is a more potent serotonin reuptake inhibitor than fluoxetine.14 It has antidepressant effects as well as antianxiety effects. FDA approval for the treatment of depression with duloxetine is pending.

5-HT1 Agonists.

Since the introduction of buspirone, research has been directed toward developing other 5-HT1A partial agonists with greater efficacy than buspirone, a faster onset of action, and fewer side effects.

GABAA receptor modulators.

GABAA receptor modulators have neurochemical properties similar to benzodiazepines. Suriclone has been evaluated in patients treated with GAD and has shown significant improvement over placebo on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety and the Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement scale. Diazepam was found to have a significantly higher number of adverse events than suriclone.15

Neuroactive peptides.

Currently a number of neuroactive peptides are being studied in the treatment of GAD, such as cholecystokinin (CCK) receptor antagonists. CCK is an important neurotransmitter found in the gut and brain and is thought to interact with other neuronal systems to cause anxiety. Research has focused on the activity at the CCKA and CCKB receptor subtypes. CI-988, a CCKB receptor antagonist, has been found to be well-tolerated, although not efficacious, in anxiety treatment.17 Neurokinin receptor antagonists have an anxiolytic-like effect in rodents, but research in humans has not been published.

Pregabalin.

Structurally, pregabalin is a GABA analog, but its biological activity resembles L-leucine. Pre-gabalin binds with high selectivity and affinity to the α2δ subunit of voltage-dependent calcium channels.

Studies17,18 comparing pregabalin with alprazolam and venlafaxine have demonstrated rapid onset of effect with pregabalin. Time to response was within 1 week with pregabalin treatment, faster than onset seen with alprazolam and venlafaxine. Pregabalin was effective in rapidly treating both the somatic and psychic symptoms of GAD and was better tolerated than venlafaxine. Common side effects included dizziness and somnolence.

Conclusion

Patients with GAD and a variety of anxiety disorders often present to primary care physicians before they present to mental health specialists. Primary care physicians, therefore, play a key role in making the diagnosis and instituting proper treatment. Physicians should begin treatment immediately and should be aggressive in reaching a goal of symptom remission. Early treatment may offset and even prevent the development of comorbid conditions and improve a patient's overall functional level. Dr. Connor encouraged physicians to consider the possibility of depressive symptoms in patients who have an anxiety disorder. A number of current treatments are effective in treating both anxiety and depressive symptoms, and future treatments have the possibility of providing faster efficacy with relatively few side effects.

REFERENCES

- Maier W, Gansicke M, and Freyberger HJ. et al. Generalized anxiety disorder (ICD-10) in primary care from a cross-cultural perspective: a valid diagnostic entity? Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000 10:29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenblatt DJ, Shader RI, Abernathy DR. Drug therapy: current status of benzodiazepines. N Engl J Med. 1983;309:410–416. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198308183090705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballanger JC. Treatment of anxiety disorders to remission. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001 62suppl 12. 5–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sramek JJ, Tansman M, and Suri A. et al. Efficacy of buspirone in generalized anxiety disorder with coexisting mild depressive symptoms. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996 57:287–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gammans RE, Stringfellow JC, and Hvizdos AJ. et al. Use of buspirone in patients with generalized anxiety disorder and coexisting depressive symptoms: a metaanalysis of 8 randomized, controlled studies. Neuro-psychobiology. 1992 25:193–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickels K, Downing R, and Schweizer E. et al. Antidepressants for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a placebo-controlled comparison of imipramine, trazodone, and diazepam. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993 50:884–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyr M, Brown CS. Nefazodone: its place among antidepressants. Ann Pharmacother. 1996;30:1006–1012. doi: 10.1177/106002809603000916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollack MH, Zanielli R, and Goddard A. et al. Paroxetine in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorders: results from a placebo-controlled, flexible dose trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001 62:350–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl AA. Sertraline in GAD: HAM-A item factor analysis. In: New Research Abstracts of the 156th Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association. 22May2003 San Francisco, Calif. Abstract NR823:307. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson JRT, Bose A, and Zheng H. Escitalopram treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, flexible dose study. In: New Research Abstracts of the 156th Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association. 22May2003 San Francisco, Calif. Abstract NR821:307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickels K, Pollack MH, and Sheehan DV. et al. Efficacy of extended-release venlafaxine in nondepressed outpatients with generalized anxiety disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2000 157:968–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery SA, Sheehan DV, and Meoni P. et al. Characterization of the longitudinal course of improvement in GAD during long-term treatment with venlafaxine. J Psychiatr Res. 2002 36:209–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PL, Durham RC. Recovery rates in generalized anxiety disorder following psychological therapy: an analysis of clinically significant change in the STAI-T across outcome studies since 1990. Psychol Med. 1999;29:1425–1435. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799001336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpa KD, Cavanough JE, Lakoski JM. Duloxetine pharmacology: profile of a dual monoamine modulator. CNS Drug Rev. 2002;8:361–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3458.2002.tb00234.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansseau M, Olie JP, and von Frenckell R. et al. Controlled comparison of the efficacy and safety of 4 doses of suriclone, diazepam, and placebo in GAD. Psychopharmacology. 1991 104:439–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pande AC, Greiner M, and Adams JB. et al. Placebo-controlled trial of the CCK-B antagonist, CI-988, in panic disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 1999 46:860–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickels K, Pollack MH, and Lydiard RB. et al. Efficacy and safety of pregabalin and alprazolam in generalized anxiety disorder. In: New Research Abstracts of the 155th Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association. 21May2002 Philadelphia, Pa. Abstract:NR162:44. [Google Scholar]

- Kasper S, Blagden M, and Seghers S. et al. A placebo-controlled study of pregabalin and venlafaxine treatment of GAD. Presented at the National Institute of Mental Health 42nd New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit Meeting. 2002 Boca Raton, Fla. [Google Scholar]

Drug names: alprazolam (Xanax and others), buspirone (BuSpar and others), clonazepam (Klonopin and others), diazepam (Diastat, Valium, and others), escitalopram (Lexapro), fluoxetine (Prozac and others), imipramine (Tofranil and others), paroxetine (Paxil and others), sertraline (Zoloft), trazodone (Desyrel), venlafaxine (Effexor).

Pretest and Objectives

Instructions and Posttest

Registration and Evaluation

Footnotes

Continuing Medical Education Faculty Disclosure

In the spirit of full disclosure and in compliance with all ACCME Essential Areas and Policies, the faculty for this CME activity were asked to complete a full disclosure statement.

The information received is as follows: Dr. Culpepper is a consultant for Forest, Janssen, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, and Wyeth. Dr. Connor has received grant/research support from Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Pure World Botanicals, and Forest; is on the speakers bureaus for Ortho-McNeil, Wyeth-Ayerst, Pfizer, Cephalon, Solvay, and Forest; is a consultant for Ancile Pharmaceuticals, Ortho-McNeil, Wyeth-Ayerst, and Pfizer; and has received other financial or material support from Dr. Wilmar Schwabe, Nutrition 21, and Cephalon.

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the CME provider, publisher, or the commercial supporter.

To cite a section from this ACADEMIC HIGHLIGHTS, follow the format below:

Conner KM. Treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: current options and future developments, pp 38–41. In: Culpepper L, chair. Effective Recognition and Treatment of Generalized Anxiety Disorder in Primary Care [ACADEMIC HIGHLIGHTS]. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2004;6:35–41