Abstract

This study aims to develop a nurse-led hypertension management model in the community setting and pilot it to an experimental trial. A total of 73 recruited participants were randomly allocated into two groups. The study group received a home visit and 2-4 telephone follow-ups from the trained community nurses assisted by nursing student volunteers. The control group received doctor-led hypertension management. Data was collected at recruitment and immediately after the 8-week program. Outcome measures included blood pressure readings, self-care adherence, self-efficacy, quality of life, and patient satisfaction. Participants from the study group led by nurses had significant improvement in self-care adherence, patient satisfaction post-intervention than those from the control group led by doctors. However, there were no statistical significant differences in blood pressure readings, quality of life and self-efficacy between the two groups. The findings show that the nurse-led hypertension management appears to be a promising way to manage hypertensive patients at the community level, particularly when the healthcare system is better integrated.

Keywords: Community, hypertension management, nurse-led, pilot study, randomized controlled trial

Introduction

Hypertension has a high prevalence rate and low control rate worldwide. Finding a way to improve blood pressure (BP) control is a major challenge. Anti-hypertensive drugs and life-style modifications are well recognised as effective BP control measures, and are thus recommended in the guidelines of many countries and regions [1-7]. Unfortunately, the rates of adherence to the BP control measures and implementation of the guidelines remain low [5,8]. Effective hypertension management should therefore incorporate essential elements to improve patient adherence. In conventional medical treatment, physicians play a primary role in BP control. However, physicians are more likely to focus on pharmacological treatment and overlook the strategies for BP control, such as interventions that involve life-style modifications and the provision of structured follow-ups to monitor the effects of treatment or intervention. There is evidence to show that interdisciplinary team-based care involving such professionals as nurses can exert positive effects on hypertension management [9]. Studies on nurse-led care show higher patient adherence and satisfaction rates compared with doctor-led care in the primary care setting, with similar effects on mortality and quality of life (QoL) [10,11]. The intervention strategies in successful nurse-led hypertension care programmes include counselling and health education [12-18], and self-management such as BP monitoring [12,13,16-18]. Compared with pharmacological treatment, these nurse-led non-pharmacological intervention strategies are lower in cost but can contribute to reducing systolic blood pressure (SBP) by 4.8 mmHg [9]. Nurse-led intervention has thus been suggested as a promising way to manage hypertensive patients, although it lacks consistent international evidence. Accordingly, researchers [19,20] have called for further evaluation of nurse-led care’s efficacy in hypertension management. As Clark et al. [20] point out, since the existing evidence comes mostly from the United States, it is necessary to obtain hypertension management evidence from other countries and regions.

In this study, a randomized controlled trial (RCT) was conducted to develop, and experimentally evaluate the effects of a model designed to guide the practice of nurse-led hypertension management in the community. The preliminary nurse-led hypertension management model was tested in practice, thereby providing evidence of and valuable insights into its feasibility and efficacy. The study has examined the difference in BP reading, self-care adherence, self-efficacy, QoL and patient satisfaction between patients who received care guided by the nurse-led hypertension management model and those who received care guided by doctor-led hypertension management.

Materials and methods

Enrolment of participants in RCT

The RCT study was conducted in a community health centre (CHC) in Hangzhou, China, with 73 participants recruited (36 in the study group and 37 in the control group). Ethical approval was obtained from the CHC involved in the study. All information was provided to the participants in written form. Signed consent forms were obtained from all participants. The inclusion criteria for study participation were: (a) a diagnosis of hypertension, (b) ≥35 years old and (c) living within the health service network of the CHC. The exclusion criteria were: (a) inability to communicate, (b) inability to be contacted by phone, (c) terminal illness, (d) co-morbidities in contradiction with the intervention programme (e.g. exercise) and (e) pregnancy.

Interventions

The study involved an 8-week intervention. The control group in the study received hypertensive care guided by the traditional doctor-led model. Such care included unstructured and irregular follow-ups with pharmacological treatment by general practitioners. These follow-ups occurred when patients visited general practitioners to get supplemental medicines in the centre. The control group received health education leaflets published by local department and the bimonthly health education lectures provided by the centre.

The study group received nurse-led hypertension management designed on the basis of the 4-C (comprehensiveness, collaboration, coordination, and continuity) framework developed by Wong et al. [21]. Comprehensiveness was assured in patient assessment and health documentation by using the Omaha System [22]. Its use allowed patients’ health problems in the environmental, psychosocial, physiological and health-related behaviours domains to be assessed, and the results of all assessments, intervention implementation and changes in health condition to be recorded systematically and dynamically. Collaboration was assured by having the trained community nurses work with other team members such as general practitioners, nursing student volunteers, coordinator and the patients themselves to manage the latter’s health condition. Coordination involved the trained community nurses organising and facilitating available resources to meet patients’ needs. The trained community nurses provided home visits. After the home visit, the trained community nurse and a nursing student volunteer provided follow-up for every patient by telephone, thereby enhancing the effects of intervention. Two monthly telephone follow-ups were provided to those whose BP at recruitment was lower than 140/90 mmHg. Four biweekly telephone follow-ups were provided to those whose BP at recruitment was 140/90 mmHg or higher. These interventions and the training offered to the community nurses were based on protocols developed with reference to guidelines [23], literature review [16] and expert consultation.

Effects of interventions

The outcome measures included systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP), self-care adherence, self-efficacy, QoL, and patient satisfaction. SBP and DBP were measured twice using a calibrated YUYUE sphygmomanometer, with patients’ average BP readings recorded [23] by the research assistants, who also collected the remainder of the outcomes through patient self-reports during face-to-face interviews carried out in the outpatient department of the CHC.

Self-care adherence was measured using the adherence form adopted in previous studies [16,21], which includes adherence to smoking cessation, alcohol restriction, salt restriction, regular physical activity, home blood pressure monitoring (HBPM) and the use of anti-hypertensive drugs. For smoking cessation and alcohol restriction, a score of 2 was given for adherence and a score of 1 for non-adherence. With respect to the remainder of adherence, a score of 3 was assigned for complete adherence, 2 for partial adherence and 1 for non-adherence. A high rate of inter-rater reliability, i.e. 0.92, was achieved for this measure.

Participants’ self-efficacy was measured using the Chinese version of the Short-form Chronic Disease Self-Efficacy Scale (CDSES) [24]. The CDSES includes six items, each of which is rated on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all confident) to 10 (totally confident). The scale’s Cronbach’s alpha coefficient in this study was 0.82.

QoL was measured using the Chinese version of the Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) [25]. The SF-36 includes eight domains of functional status: physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role-emotional and mental health. The score for each domain ranges from 0 (worst possible health status) to 100 (best possible health status). In this study, the questionnaire’s Cronbach’s alpha coefficient ranged from 0.71 to 0.94.

Patient satisfaction was measured using a scale modified from the Patients’ Satisfaction Scale employed by Wong et al. [21]. The modified scale contains ten items, ranked on a 6-point scale (5 = very satisfactory, 4 = satisfactory, 3 = fair, 2 = unsatisfactory, 1 = very unsatisfactory, 0 = not applicable). The scale’s Cronbach’s alpha coefficient in this study was 0.92.

Data analyses

All data were recorded and analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 17.0. Baseline data were compared using a chi-square test for categorical data and independent t-tests for continuous data. A paired t-test was used for BP readings, self-efficacy, and QoL to test for within-groups differences and an independent t-test to test for between-group differences. A Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare self-care adherence and patient satisfaction pre- and post-intervention, and a Mann-Whitney U-test was performed to compare the ranked scores between the two groups. Missing data were replaced by last observation values according to previously reported method [26], and the intention-to-treat analysis was performed. Two-tailed p values of < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Demographic and health characteristics

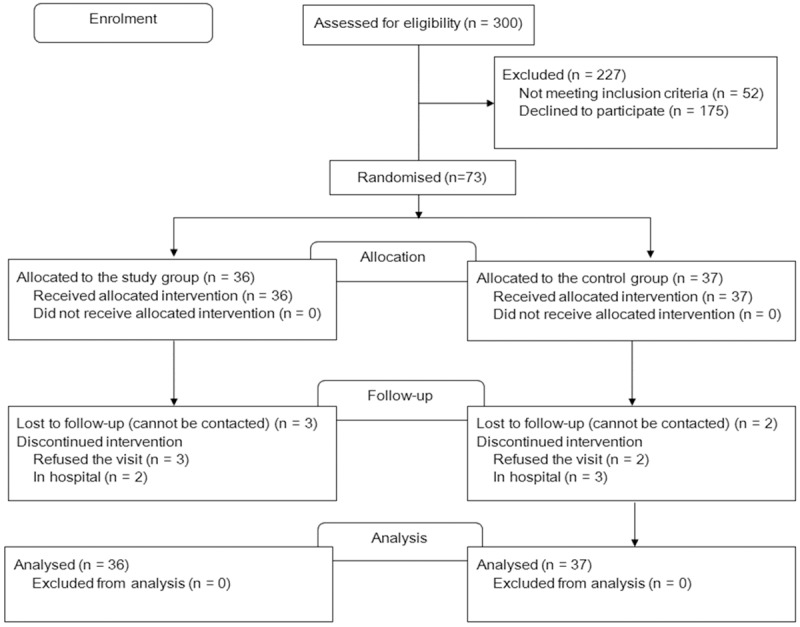

Of the 73 participants recruited (36 in the study group and 37 in the control group) in this RCT study, 15 (eight in the study group and seven in the control group) were lost to follow-up or discontinued the programme. Results relative to the 15 participants were analyzed by the intention-to-treat analysis according to previous report [26]. The patient allocation is illustrated in Figure 1. There were no statistically significant differences between the demographic and health characteristics of the patients who dropped out and those who completed the study. The participants in the study and control groups received nurse-led and doctor-led hypertension managements, respectively.

Figure 1.

Patient allocation and experimental design.

Table 1 presents the participants’ demographic and health characteristics. It can be seen that the majority of the participants were female (46, 63.0%). The mean age was 69.1 (SD = 9.7; range = 47-89) and more than half (68.5%) had a secondary school or above level of education. In addition, the majority of participants (76.7%) had one or more co-morbidities, with a mean body mass index (BWI) of 24.6 (SD = 2.9) and a mean waist circumference (WC) of 86.5 (SD = 9.3). There were no statistically significant differences between the study and control groups at baseline data. No statistically significant differences in the participants’ BP readings (Table 2) were found between the two groups after the 8-week intervention.

Table 1.

Comparison of the characteristics of the two groups (n = 73)

| Variable | Total n = 73 (%) | Study group n = 36 (%) | Control group n = 37 (%) | χ2/t-test (p value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 27 (36.99) | 15 (41.67) | 12 (32.43) | 0.67* (0.472) |

| Female | 46 (63.01) | 21 (58.33) | 25 (67.57) | |

| Educational level | ||||

| No formal education | 9 (12.32) | 5 (13.89) | 4 (10.81) | 3.96* (0.139) |

| Primary education or below | 14 (19.18) | 10 (27.78) | 4 (10.81) | |

| Secondary education or above | 50 (68.49) | 21 (58.33) | 29 (78.38) | |

| Living status | ||||

| Live alone | 10 (13.70) | 5 (13.89) | 5 (13.51) | 0.00* (1.000) |

| Live with others | 63 (86.30) | 31 (86.11) | 32 (86.49) | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 49 (67.12) | 24 (66.67) | 25 (67.57) | 0.01* (1.000) |

| Single | 24 (32.88) | 12 (33.33) | 12 (32.43) | |

| Income | ||||

| Below average | 61 (83.56) | 29 (80.56) | 32 (86.49) | 0.41* (0.750) |

| Average or above | 12 (16.44) | 7 (19.44) | 5 (13.51) | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 69.13 (9.72) | 70.42 (10.63) | 67.81 (8.82) | 1.13# (0.262) |

| [Range] | [47-89] | [47-89] | [51-84] | |

| Co-morbidity | ||||

| No co-morbidity | 17 (23.29) | 7 (19.44) | 10 (27.03) | 0.59* (0.581) |

| One or more co-morbidities | 56 (76.71) | 29 (80.56) | 27 (72.97) | |

| Body mass index | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 24.56 (2.89) | 24.33 (2.82) | 24.89 (2.91) | -1.46# (0.146) |

| [Range] | [16.24-32.53] | [16.22-29.34] | [20.42-32.53] | |

| Waist circumference | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 86.54 (9.32) | 86.46 (8.99) | 86.53 (9.45) | -0.09# (0.927) |

| [Range] | [64-123] | [64-108] | [66-123] |

Chi-square test;

Independent sample t-test.

Table 2.

Comparison of the blood pressure readings of the two groups (n = 73)

| Study group n = 36 | Control group n = 37 | Independent t-test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | t value | p value | |

| Systolic blood pressure | ||||

| Pre-test | 130.92 (10.14) | 131.95 (11.67) | -0.401 | 0.689 |

| Post-test | 130.83 (9.94) | 132.24 (13.86) | -0.498 | 0.620 |

| Paired t-test, t, p-value | 0.069, 0.945 | -0.128, 0.899 | ||

| Diastolic blood pressure | ||||

| Pre-test | 74.31(6.23) | 76.05 (8.10) | -1.032 | 0.306 |

| Post-test | 72.75 (6.64) | 75.35 (6.86) | -1.646 | 0.104 |

| Paired t-test, t, p-value | 1.324, 0.194 | 0.587, 0.561 | ||

Self-care adherence

Although the two groups had equivalent adherence scores (Table 3), the study group displayed significant improvements in salt restriction (Z = -2.357, p = 0.018), HBPM (Z = -2.646, p = 0.008) and drug use (Z = -4.179, p = 0.000) post-intervention. These results suggest that 8-week nurse-led intervention program can effectively enhance patients’ adherence to both prescriptions of anti-hypertensive drugs and recommendations of lifestyle modifications such as salt restriction.

Table 3.

Comparison of self-care adherence between the two groups (n = 73)

| Variables | Study group n = 36 | Control group n = 37 | Mann-Whitney U-test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Median (Interquartile Range) | Median (Interquartile Range) | Z value | p value | |

| Smoking cessation | ||||

| Pre-test | 2 (2-2) | 2 (2-2) | -0.433 | 0.665 |

| Post-test | 2 (2-2) | 2 (2-2) | -0.433 | 0.665 |

| Wilcoxon signed-rank test, Z, p-value | 0.000, 1.000 | 0.000, 1.000 | ||

| Alcohol restriction | ||||

| Pre-test | 2 (2-2) | 2 (2-2) | -0.052 | 0.959 |

| Post-test | 2 (2-2) | 2 (2-2) | -0.723 | 0.470 |

| Wilcoxon signed-rank test, Z, p-value | 0.000, 1.000 | -1.000, 0.317 | ||

| Salt restriction | ||||

| Pre-test | 2 (1-2) | 2 (1-2) | -0.588 | 0.557 |

| Post-test | 3 (2-3) | 2 (1-2) | -2.366 | 0.018 |

| Wilcoxon signed-rank test, Z, p-value | -2.357, 0.018 | -0.235, 0.814 | ||

| Regular physical activity | ||||

| Pre-test | 2 (2-3) | 2 (2-2) | -0.751 | 0.453 |

| Post-test | 2 (2-3) | 2 (2-2) | -1.185 | 0.236 |

| Wilcoxon signed-rank test, Z, p-value | -0.504, 0.614 | -0.000, 1.000 | ||

| Home blood pressure monitoring | ||||

| Pre-test | 3 (2-3) | 2 (2-3) | -0.536 | 0.592 |

| Post-test | 3 (2-3) | 2 (2-3) | -3.101 | 0.002 |

| Wilcoxon signed-rank test, Z, p-value | -2.646, 0.008 | -1.000, 0.317 | ||

| Use of anti-hypertensive drugs | ||||

| Pre-test | 2 (1-3) | 2 (1-3) | -1.042 | 0.297 |

| Post-test | 3 (3-3) | 2 (1-3) | -4.626 | 0.000 |

| Wilcoxon signed-rank test, Z, p-value | -4.179, 0.000 | -1.265, 0.206 | ||

Patient self-efficacy

As given in Table 4, there was a slight increase in the mean score of patient self-efficacy in the study group after intervention in comparison with the control group (6.73 versus 6.20). Table 5 shows the mean scores of eight domains of QoL in the two groups. After intervention, in the domain of general health, the mean score increased by 9.41 (from 46.53 to 55.94) in the study group (P = 0.017). When compared to the control group, a significant difference also was observed (P = 0.014). These results suggest that intervention guided by nurse-led hypertension management model is more effective on enhancing patients’ general health than the control doctor-led management.

Table 4.

Comparison of self-efficacy between the two groups (n = 73)

| Variable | Study group n = 36 | Control group n = 37 | Independent t-test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | t value | p value | |

| Pre-test | 6.20 (1.93) | 5.77 (1.98) | 0.957 | 0.342 |

| Post-test | 6.73 (1.63) | 5.87 (2.18) | 1.904 | 0.061 |

| Paired t-test, t value (p value) | -1.497 (0.143) | -0.306 (0.761) | ||

Table 5.

Comparison of quality of life between the two groups (n = 73)

| Variables | Study group n = 36 | Control group n = 37 | Independent t-test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | t value | p value | |

| Physical functioning | ||||

| Pre-test | 85.56 (12.86) | 84.05 (16.62) | 0.431 | 0.668 |

| Post-test | 84.03 (16.12) | 82.84 (19.49) | 0.285 | 0.777 |

| Paired t-test, t, p-value | 0.544, 0.590 | 0.367, 0.716 | ||

| Role physical | ||||

| Pre-test | 68.75 (41.99) | 74.32 (42.28) | -0.565 | 0.574 |

| Post-test | 67.36 (42.18) | 78.38 (38.26) | -1.169 | 0.246 |

| Paired t-test, t, p-value | 0.158, 0.875 | -0.498, 0.621 | ||

| Bodily pain | ||||

| Pre-test | 74.78 (19.14) | 72.86 (26.14) | 0.357 | 0.722 |

| Post-test | 75.58 (23.99) | 75.78 (23.61) | -0.036 | 0.971 |

| Paired t-test, t, p-value | -0.201, 0.842 | -0.564, 0.576 | ||

| General health | ||||

| Pre-test | 46.53 (11.57) | 49.89 (22.24) | 1.237 | 0.220 |

| Post-test | 55.94 (19.43) | 46.22 (12.81) | 2.532 | 0.014 |

| Paired t-test, t, p-value | 2.515, 0.017 | 0.818, 0.419 | ||

| Vitality | ||||

| Pre-test | 71.11 (13.94) | 72.70 (17.50) | -0.429 | 0.669 |

| Post-test | 72.78 (15.65) | 75.95 (14.57) | -0.896 | 0.374 |

| Paired t-test, t, p-value | -0.634, 0.530 | -1.366, 0.180 | ||

| Social functioning | ||||

| Pre-test | 85.42 (16.77) | 91.55 (12.17) | -1.786 | 0.079 |

| Post-test | 85.76 (16.13) | 88.51 (20.49) | -0.636 | 0.527 |

| Paired t-test, t, p-value | -0.133, 0.895 | 0.893, 0.378 | ||

| Role emotional | ||||

| Pre-test | 74.07 (41.49) | 79.28 (36.30) | -0.571 | 0.570 |

| Post-test | 73.15 (41.27) | 81.08 (36.47) | -0.871 | 0.387 |

| Paired t-test, t, p-value | 0.122, 0.903 | -0.264, 0.793 | ||

| Mental health | ||||

| Pre-test | 79.89 (17.12) | 85.84 (11.22) | -1.751 | 0.085 |

| Post-test | 83.56 (13.62) | 87.68 (10.77) | -1.432 | 0.157 |

| Paired t-test, t, p-value | -1.162, 0.253 | -0.954, 0.347 | ||

Patient satisfaction

As given in Table 6, the intervention effected no significant change in this domain in the control group, whereas a significant post-intervention increase was observed in the study group (t = -2.303, p = 0.021). There was also a significant difference between the groups after the intervention (t = -2.054, p = 0.040). The significant difference was detected within the study group (p = 0.021) as well as between two groups after intervention (p = 0.040). These results suggest that hypertensive patients were more satisfied with nurse-led hypertension management than the control doctor-led management.

Table 6.

Comparison of patient satisfaction between the two groups (n=73)

| Study group n = 36 | Control group n = 37 | Mann-Whitney U-test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Median (Interquartile Range) | Median (Interquartile Range) | Z value | p value | |

| Pre-test | 35.50 (0.00-48.00) | 34.00 (0.00-40.00) | -0.583 | 0.560 |

| Post-test | 40.00 (24.00-49.00) | 32.00 (0.00-40.00) | -2.054 | 0.040 |

| Wilcoxon sinned ranks test, Z value (p value) | -2.303, (0.021) | -0.430, (0.667) | ||

Discussion

In the doctor-led CHCs, doctors dominate hypertension management. This study has reported the nurse-led hypertension management model to compare its effects with a traditional doctor-led model in an experimental trial in China. In the study, we have established a nurse-led hypertension management model guided by 4-C framework [21]. When subjected to an RCT, our nurse-led model resulted in greater patient self-care adherence, satisfaction, and outcomes in some domain of QoL than the doctor-led model. Though we could not provide sufficient evidence of nurse-led intervention on reducing BP and improving self-efficacy, our study proved that the community nurses could be trained to play a key role in hypertension management at community level and contribute to improvement of patient outcome.

The study suffered two major limitations. First, just like other non-profit intervention studies conducted in the doctor-led health care organisations, it is difficult to conduct a large-scale trial. Thus, relatively small sample size in the study might affect evaluation of effects of the intervention in this study. Second, as with all single-centre study, the generalisability of our results to other healthcare settings is unknown, although the centre is a typical community health care organization.

Patient adherence is associated with clinical outcomes and health care cost. Improving patient adherence is a vital factor of effective BP control. In this study, trained community nurses enhanced patient adherence by using effective strategies such as home visit and telephone follow-ups [27]. The finding that the nurse-led intervention achieved greater patient adherence than the doctor-led control is consistent with the result of a meta-analyses study [11].

The nurse-led hypertension management model is practicable in guidance of managing hypertensive patients at the community level, while its effects on patient BP readings still need to be evaluated. In further study, efforts should be made to improve structural factors such as the health system in order to maximize the effectiveness of the nurse-led model.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Central Research Grant from the Hong Kong Polytechnic University (RPUY and 8-881Q) and a Scientific Research Grant from Zhejiang Provincial Health Department (2010KYA157). Special acknowledgements to Qinqin Hu, Linlin Yu, Liwan Ding, and Xueping Wang, who conducted interventions in the study.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL Jr, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT Jr, Roccella EJ. Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42:1206–1252. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitworth JA World Health Organization; International Society of Hypertension Writing Group. 2003 World Health Organization (WHO)/International Society of Hypertension (ISH) statement on management of hypertension. J Hypertens. 2003;21:1983–1992. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200311000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu L. Writing group of 2010 Chinese Guidelines for the management of hypertension. 2010 Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertension. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2011;39:579–615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aronow WS, Fleg JL, Pepine CJ, Artinian NT, Bakris G, Brown AS, Ferdinand KC, Forciea MA, Frishman WH, Jaigobin C, Kostis JB, Mancia G, Oparil S, Ortiz E, Reisin E, Rich MW, Schocken DD, Weber MA, Wesley DJ, Harrington RA. ACCF/AHA 2011 expert consensus document on hypertension in the elderly: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents. Circulation. 2011;123:2434–2506. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31821daaf6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.United Kingdom National Clinical Guideline Centre. Hypertension The clinical management of primary hypertension in adults Clinical Guideline 127. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Available from URL: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG127. Accessed 5 September 2014.

- 6.Hackam DG, Quinn RR, Ravani P, Rabi DM, Dasgupta K, Daskalopoulou SS, Khan NA, Herman RJ, Bacon SL, Cloutier L, Dawes M, Rabkin SW, Gilbert RE, Ruzicka M, McKay DW, Campbell TS, Grover S, Honos G, Schiffrin EL, Bolli P, Wilson TW, Feldman RD, Lindsay P, Hill MD, Gelfer M, Burns KD, Vallà EM, Prasad GVR, Lebel M, McLean D, Arnold JMO, Moe GW, Howlett JG, Boulanger J, Larochelle P, Leiter LA, Jones C, Ogilvie RI, Woo V, Kaczorowski J, Trudeau L, Petrella RJ, Milot A, Stone JA, Drouin D, Lavoie KL, Lamarre-Cliche M, Godwin M, Tremblay G, Hamet P, Fodor G, Carruthers SG, Pylypchuk GB, Burgess E, Lewanczuk R, Dresser GK, Penner SB, Hegele RA, McFarlane PA, Sharma M, Reid DJ, Tobe SW, Poirier L, Padwal RS Canadian Hypertension Education Program. The 2013 Canadian Hypertension Education Program recommendations for blood pressure measurement, diagnosis, assessment of risk, prevention, and treatment of hypertension. The Can J Cardiol. 2013;29:528–542. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, Redón J, Zanchetti A, Böhm M, Christiaens T, Cifkova R, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, Galderisi M, Grobbee DE, Jaarsma T, Kirchhof P, Kjeldsen SE, Laurent S, Manolis AJ, Nilsson PM, Ruilope LM, Schmieder RE, Sirnes PA, Sleight P, Viigimaa M, Waeber B, Zannad F Task Force Members. 2013 ESH/ESC Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) J Hypertens. 2013;31:1281–1357. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000431740.32696.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. Adherence to long-term therapies: Evidence for action. World Health Organization. Available from URL: http://www.who.int/chp/knowledge/publications/adherence_full_report.pdf. Accessed 5 September 2014.

- 9.Carter BL, Rogers M, Daly J, Zheng S, James PA. The potency of team-based care interventions for hypertension: a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1748–1755. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horrocks S, Anderson E, Salisbury C. Systematic review of whether nurse practitioners working in primary care can provide equivalent care to doctors. BMJ. 2002;324:819–823. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7341.819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keleher H, Parker R, Abdulwadud O, Francis K. Systematic review of the effectiveness of primary care nursing. Int Jo Nurs Pract. 2009;15:16–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2008.01726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rudd P, Miller NH, Kaufman J, Kraemer HC, Bandura A, Greenwald G, Debusk RF. Nurse management for hypertension. A systems approach. Am J Hypertens. 2004;17:921–927. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Artinian NT, Flack JM, Nordstrom CK, Hockman EM, Washington OGM, Jen KC, Fathy M. Effects of nurse-managed telemonitoring on blood pressure at 12-month follow-up among urban African Americans. Nurs Res. 2007;56:312–322. doi: 10.1097/01.NNR.0000289501.45284.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andersen UO, Simper AM, Ibsen H, Svendsen TL. Treating the hypertensive patient in a nurse-led hypertension clinic. Blood Press. 2010;19:182–187. doi: 10.3109/08037051003606405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baig AA, Mangione CM, Sorrell-Thompson AL, Miranda JM. A randomized community-based intervention trial comparing faith community nurse referrals to telephone-assisted physician appointments for health fair participants with elevated blood pressure. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:701–709. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1326-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chiu CW, Wong FKY. Effects of 8 weeks sustained follow-up after a nurse consultation on hypertension: a randomised trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47:1374–1382. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hotu C, Bagg W, Collins J, Harwood L, Whalley G, Doughty R, Gamble G, Braatvedt G. A community-based model of care improves blood pressure control and delays progression of proteinuria, left ventricular hypertrophy and diastolic dysfunction in Maori and Pacific patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease: a randomized contr. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation: official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2010;25:3260–3266. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pezzin LE, Feldman PH, Mongoven JM, McDonald MV, Gerber LM, Peng TR. Improving blood pressure control: results of home-based post-acute care interventions. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:280–286. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1525-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glynn LG, Murphy AW, Smith SM, Schroeder K, Fahey T. Interventions used to improve control of blood pressure in patients with hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010:D5182. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005182.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clark CE, Smith LFP, Taylor RS, Campbell JL. Nurse led interventions to improve control of blood pressure in people with hypertension: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;341:c3995. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wong FK, Mok MPH, Chan T, Tsang MW. Nurse follow-up of patients with diabetes: randomized controlled trial. J Adv Nurs. 2005;50:391–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin KS. In: The Omaha System: A Key to Practice, Documentation, and Information Management. 2nd edn. Martin KS, editor. St Louis: Saunders Elsevier; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu LS Writing group of Chinese Guidelines for the management of hypertension. In: Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertension (2005 revised version) Liu LS, editor. Beijing: People’s Medical Publishing House; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chow SK, Wong FK. The reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the Short-form Chronic Disease Self-Efficacy Scales for older adults. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23:1095–1104. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fang JQ. In: Measurements and Applications of Quality of Life. Fang JQ, editor. Beijing: Beijing Medical University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shao J, Zhong B. Last observation carry-forward and last observation analysis. Stat Med. 2003;22:2429–2441. doi: 10.1002/sim.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Verberk WJ, Kessels AGH, Thien T. Telecare is a valuable tool for hypertension management, a systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood Press Monit. 2011;16:149–155. doi: 10.1097/MBP.0b013e328346e092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]