Highlights

-

•

A 33-year-old woman presented with intermittent dull upper abdominal pain for two days. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) was performed showing a hyperdense mass in the antrum. Endoscopy and endoscopic ultrasound revealed a submucosal antral mass along the greater curvature, suspicious for a gastrointestinal (GI) stromal tumor (GIST), a laparoscopic antrectomy with Billroth I reconstruction was done.

-

•

Pathological examination revealed that the mass was a gastric glomus tumor. Gastric glomus tumors are fairly uncommon and mostly benign, with an estimated incidence of 1% of all GI soft tissue tumors.

-

•

This case may aid in improving the recognition and diagnosis of this rare entity and in differentiating it from more common GISTs and gastric carcinoids.

-

•

A built up knowledge between physicians is extremely necessary to avoid common confusion in taking the right medical approach.

Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; GI, gastrointestinal; GIST, gastrointestinal stromal tumor; EU, emergency unit; EUS, endoscopic ultrasound; SMA, smooth muscle actin; KIT, proto-oncogene c-Kit or tyrosine-protein kinase Kit or CD117; AFIP, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; AUBMC, American University of Beirut Medical Center

Keywords: Laparoscopy, Glomus Tumor, Antrum, Diagnosis

Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Gastric glomus tumors are fairly uncommon and mostly benign, with an estimated incidence of 1% of all GI soft tissue tumors. The most common GI site of involvement is the stomach, and in particular the antrum. Some cases have been discovered incidentally, but most are symptomatic presenting with GI bleeding, perforation or abdominal pain. Glomus tumors are submucosal tumors and hence mistaken with the more frequent gastrointestinal stromal tumors.

PRESENTATION OF CASE

A 33-year-old woman presented with intermittent dull upper abdominal pain for two days. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) was performed showing a hyperdense mass in the antrum. Endoscopy and endoscopic ultrasound revealed a submucosal antral mass along the greater curvature, suspicious for a gastrointestinal (GI) stromal tumor (GIST), a laparoscopic antrectomy with Billroth I reconstruction was done. Pathological examination revealed that the mass was a gastric glomus tumor.

DISCUSSION

The presented case report met all the usual standard criteria commonly used to identify glomus tumors, the uniqueness of the case lies in the occurrence of the glomus tumor in the stomach, first suspected as GIST, then confirmed as a gastric glomus tumor. The vast majority of glomus tumors of the GI tract have been described in the gastric antrum. They occur in adults of all ages with a significant female predominance (78%).

CONCLUSION

This case may aid in improving the recognition and diagnosis of this rare entity and in differentiating it from more common GISTs and gastric carcinoids. A built up knowledge between physicians is extremely necessary to avoid common confusion in taking the right medical approach.

1. Introduction

Glomus tumors are rare mesenchymal neoplasms composed of modified smooth muscle cells, closely resembling perivascular glomus bodies, with an occurrence of 1% among all soft tissue tumors.1 Though most commonly benign, they have been considered malignant in some rare cases.1 Glomus tumors are mostly found in distal extremities, but have been reported in the gastro-intestinal (GI) tract.2 The most common GI site of involvement is the stomach, and in particular the antrum. Some cases have been discovered incidentally, but most are symptomatic presenting with GI bleeding, perforation or abdominal pain. Glomus tumors are submucosal tumors and hence mistaken for the more frequent gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs).3 We present a case of a symptomatic gastric glomus tumor that was treated with laparoscopic antrectomy and Billroth I reconstruction.

2. Presentation of case

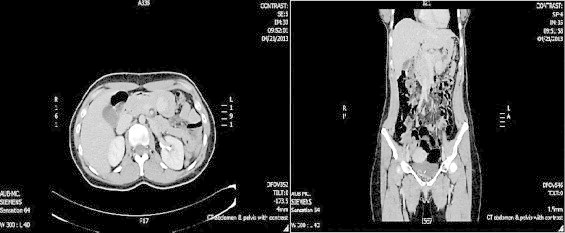

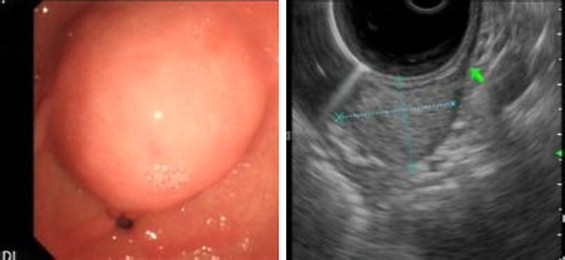

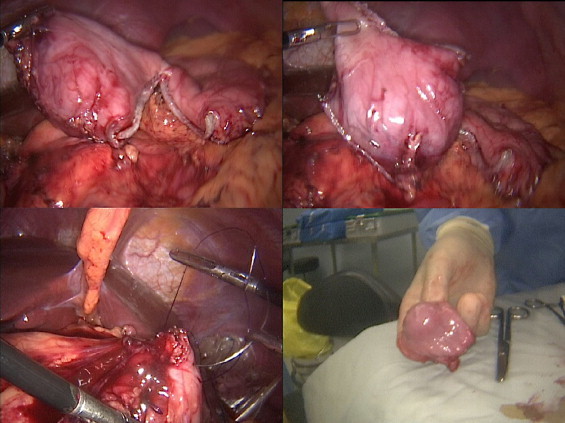

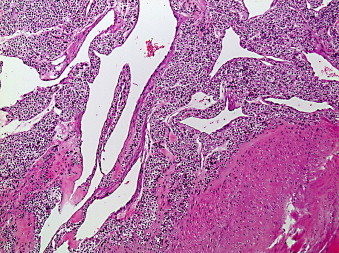

A 33-year-old female presented to the emergency unit (EU) at the American University of Beirut Medical Center (AUBMC) complaining of dull intermittent upper abdominal pain that radiated to the right flank and groin over a two-day period. No symptoms of nausea, vomiting, change in bowl habits or bleeding per rectum were reported. Direct and rebound tenderness were noted in the right lower quadrant with a negative Giordano's sign. Laboratory tests were unremarkable. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed a 2.5 cm × 2 cm hyperdense gastric lesion (Fig. 1). Upper GI endoscopy and Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) confirmed the presence of a submucosal antral mass along the greater curvature, suspicious for a GIST, hence a preoperative biopsy was not performed (Fig. 2). She was referred for surgical consultation and laparoscopic antrectomy with Billroth I reconstruction was performed because the mass was relatively large in size for wedge resection. Billroth I was preferred because tumors in certain parts of the stomach may require Billroth I or II to preclude any primary closure and to achieve gastrointestinal continuity (Fig. 3). Gross examination demonstrated a 2 × 1.6 × 1.6-cm submucosal and well-circumscribed mass (Fig. 4) and histology revealed a tumor consisting of a proliferation of round and extremely uniform cells arranged around vascular spaces of varying sizes. There was neither mitotic activity nor necrosis. No spindle cell component was identified. Immunohistochemistry confirmed that the mass stained strongly positive for smooth muscle actin (SMA), weakly positive for synaptophysin, and was negative for chromogranin and cytokeratin establishing the diagnosis of glomus tumor of the gastric antrum (Figs. 5, 6). The post-operative course of the patient was smooth. Feeding was started on day 3 post surgery and increased gradually. The patient tolerated the procedure very well with no complications throughout a follow-up period of 6 months.

Fig. 1.

CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast showing 2.5 cm × 2 cm hyperdense gastric lesion suggesting intramural tumor. (A) Axial cuts (B) coronal cuts.

Fig. 2.

(A) Round submucosal lesion noted at the pylorus. (B) Endoscopic ultrasonogrophy (EUS) shows1.7 cm × 2.5 cm slightly hyperechoic round lesion arising from the muscularis propria.

Fig. 3.

Laparoscopic resection of the tumor at the antrum using staples, hand sewn anastomsis with Billroth I reconstuction.

Fig. 4.

Gross pathology of the tumor showing intramural lesion.

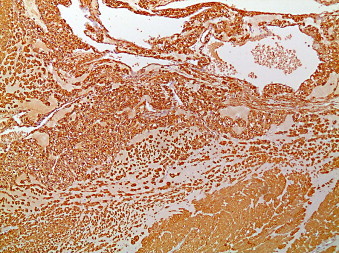

Fig. 5.

Trabeculae of tumor cells distributed next to the stomach's muscularis propria (Hematoxylin and Eosin stain 100×).

Fig. 6.

Glomus tumor of the stomach (smooth muscle actin (SMA) stain that is strongly positive in glomus cells and in the smooth muscle of the muscularis propria 100×).

3. Discussion

Glomus tumors of the GI tract are rare, representing around 1% of GI soft tissue tumors.1 They are defined as mesenchymal tumors composed of a population of modified smooth muscle cells with prominent vascular channels.4 The bulk of glomus tumors often originate in the neuromyoarterial glomus, an arteriovenous shunt that is supplied with nerve fibers performing a temperature-regulating function.1 Nearly most of the reported glomus tumors were located in the distal extremities, but they were exceptionally found in the GI tract.5 The vast majority of Glomus tumors of the GI tract have been described in the gastric antrum.1 They occur in adults of all ages with a significant female predominance (78%).6,7 Patients may present with ulcer-like symptoms such as epigastric pain, gastrointestinal bleeding or perforation in 31–35%, but some have been discovered incidentally intra-operatively or on routine endoscopy.5 Glomus tumors of the stomach are usually small with a median size of 2–3 cm7,8

Upper endoscopy generally reveals a well-defined subepithelial mass. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) findings may show a circumscribed hypoechoic mass located in the third or fourth layer with a heterogeneous pattern. On CT imaging, glomus tumors display dense, homogeneous patterns. Imaging studies, including EUS and CT are therefore limited in the diagnosis of Glomus tumors due to non-specific and overlapping features with GIST.9

The diagnosis of Glomus tumor is established on pathological examination. Three glomus tumor subtypes are generally described; solid glomus tumors, glomangiomas, and glomangiomyomas. This distinction is purely histologic depending on the relative prominence of specific components (prominent vessels in glomangiomas and prominent smooth muscle bundles in glomangiomyomas.10

The more important distinction is one between benign and malignant glomus tumors. This generally relies on the presence of certain features such as cellular atypia, mitotic activity, spindle cell areas, or frank sarcomatous change. Such findings may be focal and subtle hence the need for careful histopathologic examination of this rare neoplasm.11 Other diagnostic considerations such as carcinoid tumor and lymphoma should be easily resolved by the alert pathologist through careful morphologic examination and immunohistochemical stains.

Miettinen et al.6 reported on 32 cases of Glomus tumors of the GI tract that were referred to the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP) over an 18-year period. About half of those cases had a different diagnosis before final review (i.e.: GIST, carcinoid, lymphoma). Histologically, the tumors typically had a solid pattern of sharply demarcated, round glomus cells with prominent, mildly dilated pericytoma-like vessels. Immunohistochemically, all tumors were positive for smooth muscle actin, vimentin and calponin, and nearly all had net-like pericellular laminin and collagen type IV positivity. All tumors were negative for desmin and S-100 protein. All tumors lacked KIT expression and the GIST-specific mutations in the c-kit gene. Glomus tumors never stain positive for chromogranin and are only weakly positive for synaptophysin. One patient from Miettinen's series died of diffuse metastatic disease. While this patient's tumor lacked significant mitotic activity, it did manifest atypical features such as spindle cell growth and vascular invasion.12 The literature contains a few such reports of malignant glomus tumor arising in different parts of the GI tract.13,14

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, glomus tumors of the stomach should be considered in the differential diagnosis of gastric submucosal tumors. They cannot be distinguished from GIST on endoscopy, EUS or CT scan. Histological findings with immunohistochemical stains will allow a definitive diagnosis. Their small size and benign nature make them amenable to laparoscopic resection.7 Due to their rarity, there are no solid guidelines for follow-up. Yet, a careful step-by-step medical plan must be put ahead of time before approaching a patient with a submucosal gastric mass carrying a potential for malignant behavior. It is mandatory to carefully examine the mass histologically and immunohistochemically, to reach a definitive diagnosis. The value of such reports is to remind both surgeons and pathologists about these rare tumors of the GI tract, their potential confusion with other tumors of entirely different derivation and management algorithms, and the need to carefully assess them for the presence of atypical features that may predict malignant clinical behavior. Correctly diagnosing and classifying glomus tumors of the stomach and intestines is an essential part of providing patients with appropriate medical care and avoiding problematic and possibly negative outcomes.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

The American University of Beirut Medical Center sponsored the case report, but the efforts made for publication were made by the authors of the case.

Ethical approval

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this Case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

All surgical and clinical protocols were approved by the institutional review board (IRB) at the AUBMC and signed by the ethics committee with consent for meeting the guidelines of Lebanon's national healthcare system and in accordance with Helsinki Declaration.

Author's contributions

MK and BS performed all surgical procedures presented in the case and contributed to the study design. KR collected data. HH drafted the manuscript, FK edited the manuscript, FB added the histological part and revised the manuscript. MK and BS revised and finally approved the manuscript for submission.

Contributor Information

Hamzeh M. Halawani, Email: halawani.md@gmail.com.

Mohammad Khalife, Email: mk12@aub.edu.lb.

Bassem Safadi, Email: bs27@aub.edu.lb.

Khaled Rida, Email: kr08@aub.edu.lb.

Fouad Boulos, Email: fb17@aub.edu.lb.

Farah Khalifeh, Email: fmk14@mail.aub.edu.

References

- 1.Park J.P., Park S.C., Park C.K. A case of gastric glomus tumor. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2008;52(5):310–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang C.C., Yu F.J., Jan C.M., Yang S.F., Kuo Y.T., Hsieh J.S. Gastric glomus tumor: a case report and review of the literature. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2010;26(6):321–326. doi: 10.1016/S1607-551X(10)70046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matevossian E., Brucher B.L., Nahrig J., Feussner H., Huser N. Glomus tumor of the stomach simulating a gastrointestinal stromal tumor: a case report and review of literature. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2008;2(1):1–5. doi: 10.1159/000112862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zissis D., Zizi-Serbetzoglou A., Glava C., Grammatoglou X., Katsamagkou E., Nikolaidou M.E. Glomus tumor of the stomach: a case report. J BUON. 2008;13(4):581–584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chou K.C., Yang C.W., Yen H.H. Rare gastric glomus tumor causing upper gastrointestinal bleeding, with review of the endoscopic ultrasound features. Endoscopy. 2010;2(Suppl. 42):E58–E59. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1243827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miettinen M., Paal E., Lasota J., Sobin L.H. Gastrointestinal glomus tumors: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 32 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26(3):301–311. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200203000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee H.W., Lee J.J., Yang D.H., Lee B.H. A clinicopathologic study of glomus tumor of the stomach. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40(8):717–720. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200609000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fang H.Q., Yang J., Zhang F.F., Cui Y., Han A.J. Clinicopathological features of gastric glomus tumor. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(36):4616–4620. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i36.4616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baek Y.H., Choi S.R., Lee B.E., Kim G.H. Gastric glomus tumor: analysis of endosonographic characteristics and computed tomographic findings. Dig Endosc. 2013;25(1):80–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2012.01331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christopher D.M., Fletcher K.K.U., Fredrik M. 2013. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of the Soft and Bone Tissue. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Folpe A.L., Fanburg-Smith J.C., Miettinen M., Weiss S.W. Atypical and malignant glomus tumors: analysis of 52 cases, with a proposal for the reclassification of glomus tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25(1):1–12. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200101000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu X.D., Lu X.H., Ye G.X., Hu X.R. Immunohistochemical analysis and biological behaviour of gastric glomus tumours: a case report and review of the literature. J Int Med Res. 2010;38(4):1539–1546. doi: 10.1177/147323001003800438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gassel H.J., Klein I., Timmermann W., Kenn W., Gassel A.M., Thiede A. Presentation of an unusual benign liver tumor: primary hepatic glomangioma. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37(10):1237–1240. doi: 10.1080/003655202760373489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abu-Zaid A., Azzam A., Amin T., Mohammed S. Malignant glomus tumor (glomangiosarcoma) of intestinal ileum: a rare case report. Case Rep Pathol. 2013;2013:305321. doi: 10.1155/2013/305321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]