Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma (LGFMS) is a rare soft tissue tumor typically affecting young to middle-aged adults. Despite its otherwise benign histologic appearance and indolent nature, it can display fully malignant behavior, and recurrence and metastasis can occur even decades after diagnosis.

PRESENTATION OF CASE

Herein, we report a case of LGFMS in the buttock of a 77-year-old man. Magnetic resonance imaging uncovered a well-demarcated tumor measuring 27 × 20 mm with a slightly high intensity on T1-weighted images (WIs) and heterogeneously high intensity on T2-WIs. Histologically, the tumor was composed of bland spindle-shaped cells in a whorled growth pattern with alternating fibrous and myxoid stroma. The tumor stroma was variably hyalinized with arcades of curvilinear capillaries and arterioles with associated perivascular fibrosis. Unusual histology, such as central necrosis and cystic formation, was also noted. Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction from a formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded biopsy specimen revealed a FUS-CREB3L2 gene fusion (exon6/int/exon5), leading to the diagnosis of LGFMS.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the second oldest patient to be diagnosed with LGFMS.

CONCLUSION

At the time of this report, the patient was alive with no evidence of the disease 4 months after diagnosis without any adjuvant therapy.

Keywords: Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma, FUS-CREB3L2, Fusion gene, Elderly patient

1. Introduction

Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma (LGFMS) is a rare soft tissue tumor that typically affects young to middle-aged adults.1,2 A large series of LGFMS cases demonstrated that the median age of onset for this tumor is 34 years (range, 3–78 years).3 Histologically, LGFMS is composed of bland spindle-shaped cells in a whorled growth pattern, arranged in alternating myxoid and collagenized areas, along with curvilinear capillaries and characteristic arterioles with perivascular fibrosis. Heterotopic ossification and cyst formation have also been reported in these tumors.4,5 While LGFMS usually exhibits otherwise benign histologic appearance, a subset of tumors have been reported to show indolent progression, with many cases developing recurrence or metastasis decades later, mainly to the lung. Cytological atypia and tumor necrosis is absent in LGFMS.6 However, approximately 30% of tumors have focal areas of intermediate- to high-grade sarcoma as shown by hypercellularity, nuclear enlargement, hyperchromatism, necrosis, and high mitotic activity (>5/50 high-powered fields), but the presence of these histologic features is not associated with patient survival.3,5 Furthermore, approximately 40% of cases have focal areas of hypocellular collagen cores rimmed by epithelioid fibroblasts, referred to as collagen pseudo-rosettes. Cases of prominent collagen pseudo-rosettes are referred to as hyalinizing spindle cell tumors with giant rosettes.7

A diagnosis of LGFMS is often difficult by a small biopsy specimen that can lead to a misdiagnosis of malignant tumors as benign or as tumor-like lesions including nodular fasciitis, schwannoma, desmoid-type fibromatosis, neurofibroma, and myxofibrosarcoma.8–10 A recent study reported up-regulation of the mucin 4 (MUC4) gene in LGFMS compared to histologically similar tumors and lesions,10,11 and MUC4 immunostaining was a sensitive and specific marker of LGFMS in appropriate morphologic context.2,7 Several recent studies demonstrated that more than 90% of LGFMS have a balanced chromosomal translocation t(7;16) (q32–34;p11) leading to the fusion of the FUS and CREB3L2 genes, while a minority of cases have a t(11;16) (p11;p11) translocation leading to the fusion of the FUS and CREB3L1 genes.1,2,7–9,12 In one report, a small number of LGFMS cases contained EWSR-CREB3L1 gene fusions.7,13

Here, we report a rare case of LGFMS with central hemorrhagic necrosis in a 77-year-old male patient. Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) from a formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) biopsy specimen revealed FUS-CREB3L2 gene fusion (exon6/int/exon5), leading to the diagnosis of LGFMS. To the best of our knowledge, this is the second oldest patient to be reported with LGFMS.

2. Case report

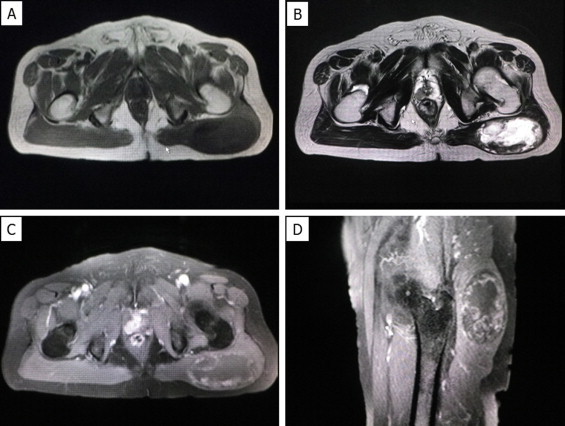

A 77-year-old man was referred to our hospital with a painless mass in the left buttock, which had been gradually growing since he first noticed it 10 years previously. A physical examination revealed an elastic hard mass in the left buttock, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a well-demarcated tumor measuring 70 mm in maximum diameter with central hematoma formation. The mass showed low intensity on T1-weighted images (WIs), heterogeneously high intensity on T2-WI (Fig. 1A and B), and heterogeneously high signal intensity on fat-suppressed T1-WI (Fig. 1C and D). Chest and pelvic computed tomography (CT) revealed no evidence of metastatic lesion.

Fig. 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the left buttock of a 77-year-old patient. MRI revealed a well-defined mass in the left buttock. The mass showed low signal intensity compared to the skeletal muscle on T1-weighted images (WIs) (A) and heterogeneously high signal intensity on T2-WIs (B). The mass had heterologously mixed low to slightly high signal intensity compared to the skeletal muscle on fat-suppressed T1-WIs (C: coronal, D: sagittal).

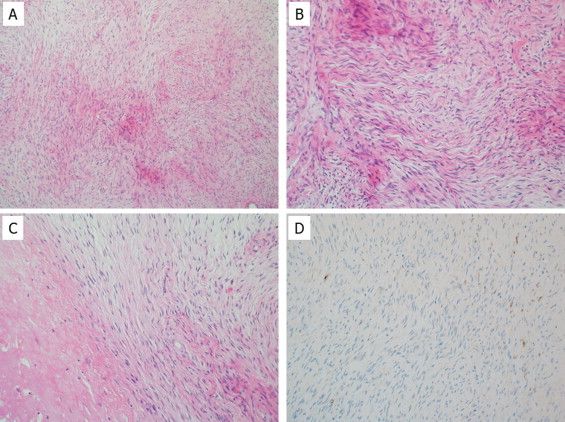

Histopathologically, the tumor was composed of bland spindle-shaped cells with a whorled growth pattern on biopsy specimen. The tumor stroma was fibrous, and alternating fibrous and myxoid stroma characteristic of LGFMS were unclear (Fig. 2A–C). The tumor showed no nuclear pleomorphism, high cellularity. Focally, tumor cells exhibited wavy appearance. Necrotic area was also observed at the edge of the specimen. Mitosis was not observed. Differential diagnosis on conventional hematoxylin and eosin staining included desmoid-type fibromatosis, schwannoma, and LGFMS. Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells were negative for S-100 protein (Fig. 2D) and nuclear staining of β-catenin, which are typically present in desmoid-type fibromatosis.

Fig. 2.

Tumor histology of the biopsy specimen. Tumor cells were proliferating in the fibrous stroma, but alternating fibrous and myxoid areas were unclear (A). Some of the tumor cells showed wavy nuclei, and nuclear atypia was not evident on high-power view (B). Degenerative area with focal necrosis was present at the periphery of the tumor (C). Immunohistochemically, tumor cells were negative for S-100 protein (D).

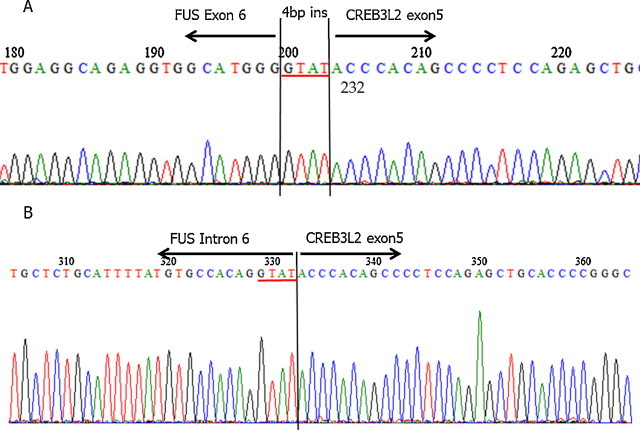

To determine the presence of FUS-CREB3L1 or FUS-CREB3L2 fusion genes in the tumor, we performed RT-PCR on FFPE tumor tissue. Briefly, five 10-μm thick paraffin sections were cut from the paraffin-embedded block. RNA was isolated using the RNeasy FFPE kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany), purified, and reverse transcribed to cDNA using the Superscript first-strand synthesis system for RT-PCR (Invitrogen, CA, USA). The primer sequences used for the amplification in this study have been previously described.14 The PCR product was separated on a 2% agarose gel, and the PCR product of the appropriate size was cut from the gel and sequenced. Sequencing confirmed the presence of a FUS-CREB3L2 fusion gene in this tumor. This gene fusion occurred between the end of exon 6 of FUS and part of exon 5 of CREB3L2 with a 4-bp insertion of unknown origin (Fig. 3A). Genomic DNA-based long PCR revealed a gene fusion between the part of intron 6 of FUS and part of exon 5 of CREB3L2. The 4-bp sequence at the end of intron 6 was identical to that of a 4-bp insertion of the FUS-CREB3L2 fusion gene, suggesting that the 4-bp insertion was probably derived from the junctional region of the fusion gene (Fig. 3B). Thus, the fusion gene in this case was exon6/int6/exon5 of the FUS-CREB3L2.

Fig. 3.

Detection of a FUS-CREB3L2 fusion in the LGFMS tumor. RT-PCR on FFPE-derived RNA was performed. DNA sequencing revealed a fusion between FUS exon 6 and part of CREB3L2 exon 5 with a 4-bp insertion (red underline) of unknown origin (A). Genome sequencing of the fusion gene revealed that the sequence of the 4-bp insertion (red underline) at the junctional region of cDNA sequence was identical to that of the last 4-bp sequence of intron 6 of FUS at the junctional region (B).

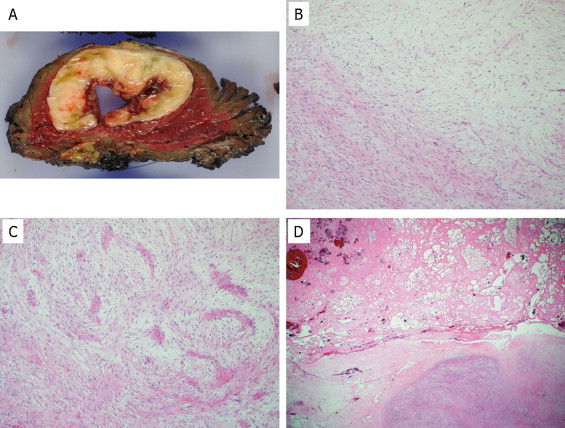

A wide resection of the tumor was performed under a diagnosis of LGFMS. Macroscopically, the resected surface of the surgical specimen was whitish-gray with partial myxoid appearance (Fig. 4A). Central hemorrhagic necrosis was also observed. Pathological analysis of the resected tumor revealed characteristic alternating fibrous and myxoid stroma with occasional cystic formation (Fig. 4B–D). Four months after diagnosis, the patient was alive with no evidence of the disease without any adjuvant therapy.

Fig. 4.

Tumor histology of the resected tumor. The surgically resected intramuscular tumor macroscopically showed a necrotic area with cystic change in the center of the tumor (A). Histologically, the surgically resected tumor was composed of an admixture of myxoid and fibrous areas (B). A whorled growth pattern with bland spindle-shaped tumor cells was observed (C). Massive hemorrhagic necrosis was observed at the center of the tumor (D).

3. Discussion

LGFMS can occur at any age, but typically affects young to middle-aged adults.1,2 Two large studies on LGFMS reported that patient age at the time of diagnosis ranges between 6–52 years and 3–78 years, respectively.3,5 In the current case, with the long duration of the tumor and cystic changes on MRI, the differential diagnosis on biopsy specimen included ancient/degenerative schwannoma by less atypical spindle shaped cells in the fibrous stroma, because alternating fibrous and myxoid stroma were unclear on the biopsy specimen. Low-grade myxofibrosarcoma (LGMFS) was also an important differential diagnosis considering the age of this patient. Patients with LGMFS are reported to be significantly older than those with LGFMS, and LGMFS more frequently occurs in a superficial location.6 Furthermore, desmoid-type fibromatosis would clinically and radiolodically be also another important differential diagnosis in this tumor, because cystic changes in desmoid tumors have been reported in a few cases, particularly those arising from the pancreas.15–17 Desmoid-type fibromatosis is a locally aggressive infiltrative intra-muscular fibrous tumor, in spite of benign histologic feature. Frequent recurrences can be clinically observed even after wide resection. A “wait-and-see” strategy is, at the present time, preferred in case of asymptomatic or non-progressive disease. Medical treatment such as cyclooxygenase-2 selective inhibitor is another choice for the patients with desmoid-type fibromatosis.18 As we can see in this case, the importance of molecular pathological diagnosis is clinically increasing, especially in the field of soft tissue sarcomas, because the definite diagnosis made by the molecular pathology such as RT-PCR and specific genetic testing sometimes leads to the application of the tumor specific therapy,19 although so far there is no specific molecular therapy targeted for the FUS-CREB3L2 or FUS-CREB3L1 gene fusion. In this case, deep location of the tumor and the characteristic histological features of bland spindle cells arranged in a whorled pattern with alternating fibrous and myxoid stroma on the surgically resected tumor confirmed the diagnosis of LGFMS. To the best of our knowledge, the current patient at 77 years of age appears to the second elderly patient diagnosed with LGFMS. Recently, LGFMS was shown to be associated with gene fusions involving CREB3-family genes, which encode members of the basic leucine zipper family of transcription factors.20 The majority of LGFMS cases (95%) have a fusion of the FUS-CREB3L2, and a minority of cases (5%) have a FUS-CREB3L1 gene fusion. In addition, a small number of cases have EWSR-CREB3L1 gene fusions.7 The present case harbored an exon6/exon5 type FUS-CREB3L2 fusion gene. Although a 4-bp insertion of unknown origin was observed at the junctional region, genome sequencing of the fusion gene revealed that this 4-bp insertion was likely derived from intron 6 at the junctional region.

Approximately 30% of LGFMS have focal areas of intermediate- to high-grade sarcoma, which is inconsistent with a definition of low-grade sarcoma,3 and tumor necrosis is described to be rare or absent in LGFMS.3,5,6 In this case, hypercellularity, increased mitotic activity, and nuclear enlargement were seldom observed throughout the lesion; however, central hemorrhagic necrosis was observed. This is probably due to the long-time duration of the tumor and the physical compression of the tumor.

In summary, we report a rare case of LGFMS with central hemorrhagic necrosis in a 77-year-old man. To the best of our knowledge, this is the second elderly patient to be diagnosed with LGFMS. Although the patient was disease-free at 4 months after surgery, further long-term follow up is needed.

Conflict of interest

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This work was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for General Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture (#26670286 to Tsuyoshi Saito, and #25861342 to Yoshiyuki Suehara), Tokyo, Japan.

Ethical approval

We obtained written and signed consent to publish this case report from the patient.

Author contribution

Wrote this manuscript: Aiko Kurisaki-Arakawa, Takashi Yao, Tsuyoshi Saito. Performed PCR to detect fusion gene: Keisuke Akaike, Tsuyoshi Saito. Diagnosed this case: Aiko Kurisaki-Arakawa, Ran Tomomasa, Atsushi Arakawa, Tsuyoshi Saito. Performed surgical procedure for this patient: Yoshiyuki Suehara, Tatsuya Takagi, Kazuo Kaneko.

References

- 1.Sedrak M.P., Parker D.C., Gardner J.M. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma with nuclear pleomorphism arising in the subcutis of a child. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:134–138. doi: 10.1111/cup.12245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dobin S.M., Malone V.S., Lopez L., Donner L.R. Unusual histologic variant of a low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma in a 3-year-old boy with complex chromosomal translocations involving 7q34, 10q11.2, and 16p11.2 and rearrangement of the FUS gene. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2013;16:86–90. doi: 10.2350/12-07-1225-CR.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Folpe A.L., Lane K.L., Paull G., Weiss S.W. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma and hyalinizing spindle cell tumor with giant rosettes: a clinicopathologic study of 73 cases supporting their identity and assessing the impact of high-grade areas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1353–1360. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200010000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee A.F., Yip S., Smith A.C., Hayes M.M., Nielsen T.O., O’Connell J.X. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma of the perineum with heterotopic ossification: case report and review of the literature. Hum Pathol. 2011;42:1804–1809. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2011.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans H.L. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma: a clinicopathologic study of 33 cases with long-term follow-up. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1450–1462. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31822b3687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oda Y., Takahira T., Kawaguchi K., Yamamoto H., Tamiya S., Matsuda S. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma versus low-grade myxofibrosarcoma in the extremities and trunk. A comparison of clinicopathological and immunohistochemical features. Histopathology. 2004;45:29–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2004.01886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lau P.P., Lui P.C., Lau G.T., Yau D.T., Cheung E.T., Chan J.K. EWSR1-CREB3L1 gene fusion: a novel alternative molecular aberration of low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:734–738. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31827560f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maretty-Nielsen K., Baerentzen S., Keller J., Dyrop H.B., Safwat A. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma: incidence, treatment strategy of metastases, and clinical significance of the FUS gene. Sarcoma. 2013:256280. doi: 10.1155/2013/256280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Menon S., Krivanek M., Cohen R. Low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma, a deceptively benign tumor in a 5-year-old child. Pediatr Surg Int. 2012;28:211–213. doi: 10.1007/s00383-011-3024-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doyle L.A., Möller E., Dal Cin P., Fletcher C.D., Mertens F., Hornick J.L. MUC4 is a highly sensitive and specific marker for low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:733–741. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318210c268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Möller E., Hornick J.L., Magnusson L., Veerla S., Domanski H.A., Mertens F. FUS-CREB3L2/L1-positive sarcomas show a specific gene expression profile with upregulation of CD24 and FOXL1. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:2646–2656. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Odem J.L., Oroszi G., Bernreuter K., Grammatopoulou V., Lauer S.R., Greenberg D.D. Deceptively benign low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma: array-comparative genomic hybridization decodes the diagnosis. Hum Pathol. 2013;44:145–150. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2012.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mertens F., Fletcher C.D., Antonescu C.R., Coindre J.M., Colecchia M., Domanski H.A. Clinicopathologic and molecular genetic characterization of low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma, and cloning of a novel FUS/CREB3L1 fusion gene. Lab Invest. 2005;85:408–415. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsuyama A., Hisaoka M., Shimajiri S., Hayashi T., Imamura T., Ishida T. Molecular detection of FUS-CREB3L2 fusion transcripts in low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma using formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue specimens. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:1077–1084. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000209830.24230.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rao R.N., Agarwal P., Rai P., Kumar B. Isolated desmoid tumor of pancreatic tail with cyst formation diagnosed by beta-catenin immunostaining: a rare case report with review of literature. JOP. 2013;14:296–301. doi: 10.6092/1590-8577/1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pho L.N., Coffin C.M., Burt R.W. Abdominal desmoid in familial adenomatous polyposis presenting as a pancreatic cystic lesion. Fam Cancer. 2005;4:135–138. doi: 10.1007/s10689-004-1923-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amiot A., Dokmak S., Sauvanet A., Vilgrain V., Bringuier P.P., Scoazec J.Y. Sporadic desmoid tumor. An exceptional cause of cystic pancreatic lesion. JOP. 2008;9:339–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mignemi N.A., Itani D.M., Fasig J.H., Keedy V.L., Hande K.R., Whited B.W. Signal transduction pathway analysis in desmoid-type fibromatosis: transforming growth factor-β. COX2 and sex steroid receptors. Cancer Sci. 2012;103:2173–2180. doi: 10.1111/cas.12037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lovly C.M., Gupta A., Lipson D., Otto G., Brennan T., Chung C.T. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors harbor multiple potentially actionable kinase fusions. Cancer Discov. 2014;4:889–895. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Storlazzi C.T., Mertens F., Nascimento A., Isaksson M., Wejde J., Brosjo O. Fusion of the FUS and BBF2H7 genes in low grade fibromyxoid sarcoma. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:2349–2358. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]