Abstract

The effects of the inhalation of Cymbopogon martinii essential oil (EO) and geraniol on Wistar rats were evaluated for biochemical parameters and hepatic oxidative stress. Wistar rats were divided into three groups (n = 8): G1 was control group, treated with saline solution; G2 received geraniol; and G3 received C. martinii EO by inhalation during 30 days. No significant differences were observed in glycemia and triacylglycerol levels; G2 and G3 decreased (P < 0.05) total cholesterol level. There were no differences in serum protein, urea, aspartate aminotransferase activity, and total hepatic protein. Creatinine levels increased in G2 but decreased in G3. Alanine aminotransferase activity and lipid hydroperoxide were higher in G2 than in G3. Catalase and superoxide dismutase activities were higher in G3. C. martinii EO and geraniol increased glutathione peroxidase. Oxidative stress caused by geraniol may have triggered some degree of hepatic toxicity, as verified by the increase in serum creatinine and alanine aminotransferase. Therefore, the beneficial effects of EO on oxidative stress can prevent the toxicity in the liver. This proves possible interactions between geraniol and numerous chemical compounds present in C. martinii EO.

1. Introduction

Plants synthesize around 200,000 secondary metabolites or specialized phytochemicals, of which essential oils (EOs) constitute an important group [1]. These compounds can be extracted from plant tissues (e.g., stem, leaves, flowers, and roots) by several procedures (e.g., hydrodistillation and steam distillation) [2]. These compounds are mostly terpenes, which are commonly used in pharmaceutical industries and have therapeutic benefits and promote welfare, especially when used in aromatherapy procedures [3].

Cymbopogon martinii (Roxb.), Watson, popularly known as palmarosa, exhibits beneficial effects on several central nervous system pathologies, mainly neuralgia, epileptic, and anorexia [4]. There are a few reports on its effects; still C. martinii has attracted many researchers' attention due to its antimicrobial, antigenotoxic, and antioxidant activities [5–8]. Countries such as India, Brazil and Madagascar have the practice to produce EOs from this plant.

Geraniol, the major constituent of C. martinii EO, is an acyclic monoterpenoid that is abundant in many plants [9]. It may represent a new class of therapeutic agents against pancreatic [10] and colon cancers [11] and has several biological properties, including antimicrobial, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities [12]. Geraniol is also an important constituent of ginger, lemon, lime, lavender, nutmeg, orange and rose EOs [13]. Also, it is used as a flavoring agent and was determined to be safe at the current levels of intake by the Joint Expert Committee on Food Additives of Food and Agriculture Organization—FAO/World Health Organization—WHO [14].

Aromatherapy is a traditional treatment that uses EOs. Its effects begin when the aromatic molecule passes through the nasal cavity and adheres to the olfactory epithelium, causing nerve stimulation directly to the hippocampus and limbic amygdaloidal body. This consequently triggers stimuli that control the autonomic nervous system and internal secretory control by changing a number of vital reactions [15]. The inhalation of aromatic compounds present in EOs is the reason for the name “aromatherapy” and this therapy may have sedating or stimulating effects on the individual [16].

Reports in the literature describe the benefits of using EOs in aromatherapy on the wellbeing of individuals, including improvements in mood, stress, anxiety, depression, and chronic pain, and promote so therapeutic, psychological, and physiological effects [17]. The inhalation of EOs elevated blood pressure and renal sympathetic activity, which enforces the idea that these components act in the central nervous system and pass through the blood-brain barrier [18].

Volatile organic compounds are highly lipophilic and may easily cross the blood-brain barrier and easily exert their neuropharmacological and toxicological effects. While studies on the toxic effects of these compounds are relatively easy to perform, the central effects induced by the perception of odor (e.g., in aromatherapy) are inherently complex. This is why the toxicological studies performed using volatile compounds are much more advanced [19].

Many studies have been conducted in vitro with the purpose of verifying the biological properties of EOs [2, 17, 20]; usually they are performed using in vitro assays. On the other hand, when the tests are performed in vivo, the products are usually administered in their liquid forms (e.g., by gavage or intraperitoneal), with few studies in the volatile state (i.e., by inhalation) [21]. Furthermore, EOs are used as flavoring agents in food products [14] and are also used in dermatology and in the fragrance and cosmetics industries. Specifically, geraniol is extensively used in the manufacture of both household and cosmetics products [12].

Since people are often use EOs, it is important to evaluate the possible hepatotoxic effects of these oils. Liver is the main detoxification organ; the catabolism of both endogenous and exogenous compounds takes place in the liver. As a result it is exposure to toxic agents which can cause drug-induced hepatic dysfunction. Therefore, studies on serum activity of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST), which are biomarkers of liver damage, are important. The serum activity of ALT and AST is frequently used in clinical settings for diagnostic hepatic toxicity [22].

Numerous chronic degenerative diseases are associated with oxidative stress, which occurs when there is excess formation of reactive oxygen species (e.g., superoxide, hydroxyl, and hydrogen peroxide) and insufficient defense by the antioxidant system (enzymatic and nonenzymatic). This imbalance between pro- and antioxidants may cause cell injury and death, which consequently lead to tissue dysfunction [23, 24]. It is well established that oxidative stress plays a fundamental role in the pathogenesis of hepatic disease, especially nonalcoholic steatohepatitis [25]. In addition, during hepatic catabolism of xenobiotics, excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) occurs [26].

Our aim was to investigate the effect of inhalation of the C. martinii EO and geraniol on serum biochemical parameters, biomarkers of hepatotoxicity, and oxidative stress in hepatic tissue.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cymbopogon martinii EO and Geraniol

C. martinii EO was supplied by the company By Samia Aromaterapia (São Paulo, SP) and showed the following chemical composition: geraniol (57.5%), geranyl acetate (13.6%), linalool (1.7%), β-caryophyllene (1.1%), and ocimene (0.3%) found by gas chromatography-mass spectrometer (GC-MS). The geraniol with 98% of purity was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

2.2. Animals and Experimental Procedure

The experimental procedure was approved by the Ethical Committee from Institute of Biological Science, São Paulo State University, Botucatu, Brazil, and the animals experiments were carried out in accordance with the principles and guidelines of the Canadian Council on Animal Care as outlined in the Guide to the Care and Use of Experimental Animals.

Male Wistar rats (290–310 g) were reared in polypropylene cages maintained in a controlled environment (temperature 22 ± 3°C; 50–55% humidity; and a 12-hour light : dark cycle), with free access to water and food (Purina Ltd., Campinas, SP, Brazil).

The rats were randomly distributed into three groups (n = 8). The rats in the control group (G1) received saline solution by inhalation (saline = 0.9% g/v). The G2 group received geraniol by inhalation and the G3 group received C. martinii EO by inhalation.

The rats from all groups were placed individually into chambers (180 mm × 300 mm × 290 mm) adapted from de Almeida et al. [27] and submitted to inhalation of geraniol (8.36 mg geraniol/L of air, which corresponds to 136.2 μL of geraniol/perspex box 14.5 L of air) and C. martinii EO (13.73 mg of C. martinii EO/L of air, which corresponds to 227 μL of C. martinii EO/perspex box 14.5 L of air) for 10 minutes every 48 hours for 30 days. The geraniol concentration was calculated from the amount of geraniol found in the C. martinii EO.

Food and water consumption were measured daily at the same time and body weights were determined once a week.

2.3. Biochemical Measurements and Oxidative Stress

After 30 days, the animals were fasted overnight (12–14 h) and euthanized by cervical decapitation under anesthesia (solution containing 10% ketamine chloride and 2% xylazine chloride with a dose of 0.1 mL/100 g body weight). Blood was collected and the serum was obtained by centrifugation at 6000 rpm for 15 minutes. Serum glucose was determined using an enzymatic colorimetric method after incubation with glucose oxidase/peroxidase. The total amount of protein was estimated using the biuret reagent and the total cholesterol concentration was determined using the cholesterol esterase/oxidase enzymatic procedure. Triacylglycerols levels were measured by enzymatic hydrolysis and the final formation of quinoneimine, which is proportional to the concentration of triacylglycerols present in the sample. Serum urea was determined by addition of urease and phenol-hypochloride, which leads to the formation of an indophenol-blue complex. The serum creatinine levels were estimated using a reaction with picric acid in alkaline buffer to form a yellow-orange complex, whose color intensity is proportional to the creatinine concentration in the sample. ALT and AST activities were determined by using pyruvate and oxaloacetate as substrates, wherein NADH is converted into NAD+ proportional to the activities of these enzymes. Hepatic samples (200 mg) were removed and homogenized in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, using a Teflon-glass Potter-Elvehjem homogenizer. The homogenate was centrifuged (10,000 g for 15 minutes) and the supernatant was used to determine the concentration of hepatic lipid hydroperoxide (LH) and activities of antioxidant enzymes. Lipid hydroperoxide activity was determined by the oxidation of Fe+2 in the presence of a reactive mixture containing methanol, xylenol orange, sulfuric acid, and butylated hydroxytoluene. Catalase activity was assayed using phosphate buffer containing hydrogen peroxide. The activity of glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) was determined in the presence of phosphate buffer, NADPH2, reduced glutathione, and glutathione reductase. Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity was assayed according to the method by measuring the rate of reduction of nitroblue-tetrazole (NBT) in the presence of free radicals generated by hydroxylamine.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as the mean ± SD. The statistical significance between the groups was assessed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey's test to compare the means of the experimental group. The probability with P ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

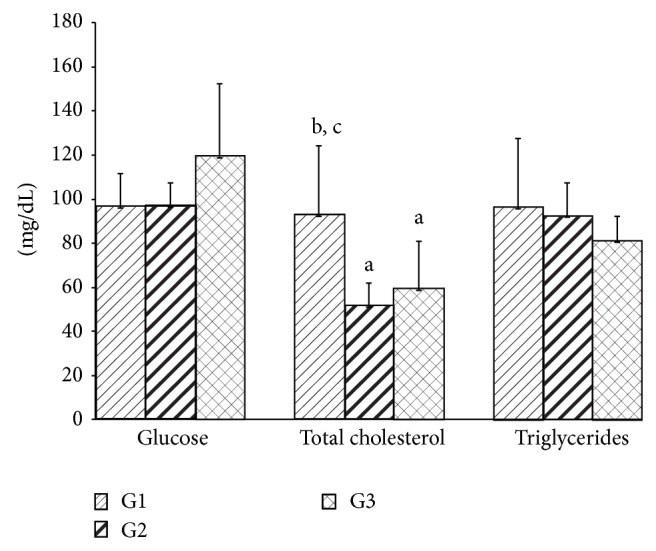

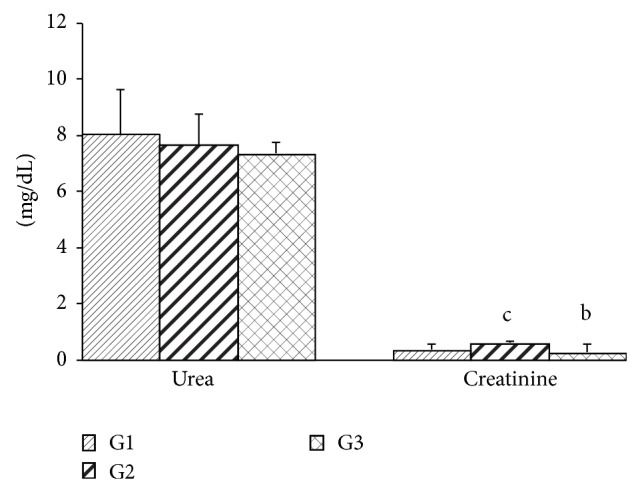

Inhalation of geraniol (G2) and of C. martinii EO (G3) had no effects on final body weight, body weight gain, and food intake of the rats (Table 1). No alteration in total hepatic protein was observed. While no significant differences were observed in the glycemia and triacylglycerol levels, geraniol (G2) and C. martinii EO (G3) decreased (P ≤ 0.05) total cholesterol levels when compared with the control group G1 (Figure 1). There were no significant differences in serum urea levels between the groups. Creatinine levels increased in the presence of geraniol but decreased in the presence of C. martinii EO (G3; Figure 2).

Table 1.

General characteristics and serum protein levels after 30 days for all experimental groups.

| Parameters | Groups | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | G2 | G3 | |

| Final body weight g | 348.57 ± 43.65 | 328.40 ± 29.82 | 320.98 ± 39.90 |

| Body weight gain g | 37.47 ± 9.25 | 36.86 ± 8.22 | 38.53 ± 17.06 |

| Final food consumption g/day | 20.30 ± 4.40 | 19.25 ± 4.14 | 18.52 ± 3.78 |

| Final water consumption mL/day | 248.75 ± 21.84c | 248.75 ± 16.20c | 211.88 ± 10.67a,b |

| Serum protein g/dL | 5,13 ± 0,83 | 5,39 ± 1,39 | 5,95 ± 1,13 |

Values are given as the mean ± SD for each group of eight animals. aSignificantly different from G1; P ≤ 0.05; bsignificantly different from G2; P ≤ 0.05; and csignificantly different from G3; P ≤ 0.05. G1: untreated control; G2: treated with geraniol; and G3: treated with essential oil.

Figure 1.

Serum glucose, total cholesterol, and triglycerides levels after 30 days for all experimental groups. Values are given as the mean ± SD for each group of eight animals. aSignificantly different from G1; P ≤ 0.05; bsignificantly different from G2; P ≤ 0.05; and csignificantly different from G3; P ≤ 0.05. G1: untreated control; G2: treated with geraniol; and G3: treated with essential oil.

Figure 2.

Serum urea and creatinine levels after 30 days for all experimental groups. Values are given as the mean ± SD for groups of eight animals each. aSignificantly different from G1; P ≤ 0.05; bsignificantly different from G2; P ≤ 0.05; csignificantly different from G3; P ≤ 0.05. G1: untreated control; G2: treated with geraniol; G3: treated with essential oil.

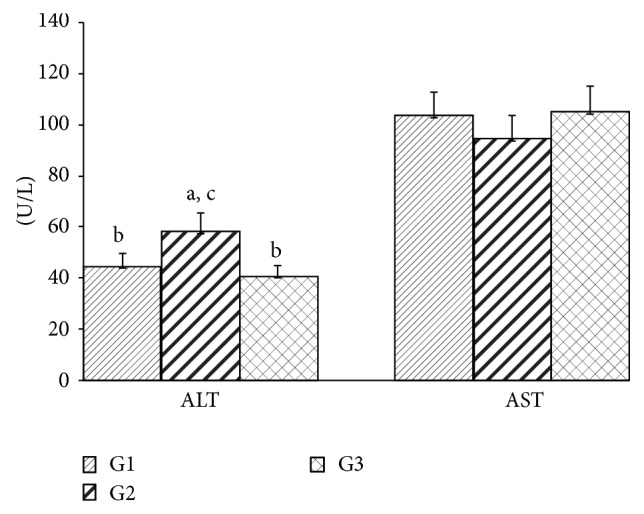

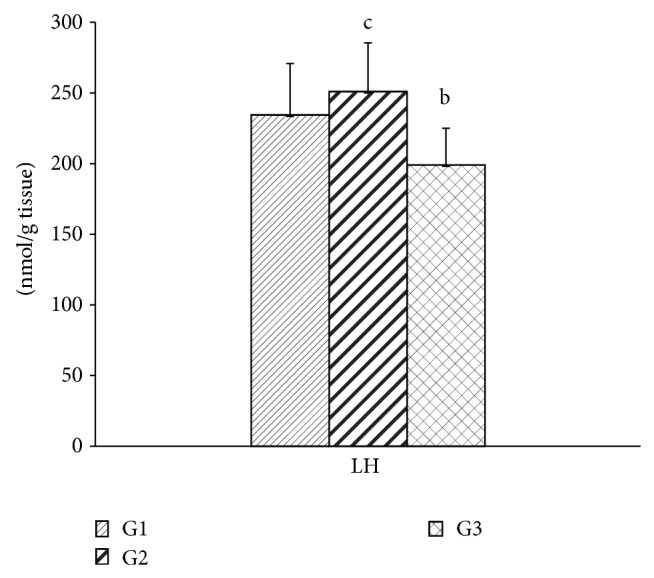

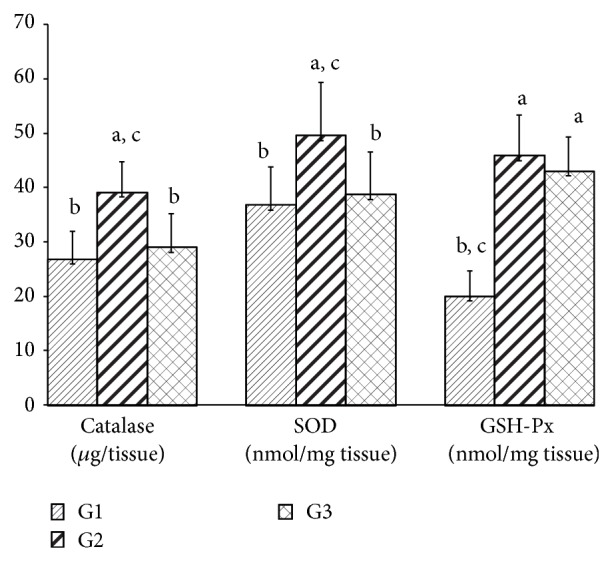

ALT activity was higher in the group exposed to geraniol when compared to the other groups, which did not differ from each other. No change was found in the AST activity between the groups (Figure 3). LH was higher in the G2 group than in the G3 group (Figure 4). Catalase and SOD activities were higher in the G3 group when compared to the other groups. Both geraniol and C. martinii EO increased GSH-Px when compared to the control rats (Figure 5).

Figure 3.

Serum activity of ALT and AST after 30 days for all experimental groups. Values are given as the mean ± SD for each group of eight animals. aSignificantly different from G1; P ≤ 0.05; bsignificantly different from G2; P ≤ 0.05; and csignificantly different from G3; P ≤ 0.05. G1: untreated control; G2: treated with geraniol; and G3: treated with essential oil.

Figure 4.

Hepatic lipid hydroperoxide levels after 30 days for all experimental groups. Values are given as the mean ± SD for each group of eight animals. aSignificantly different from G1; P ≤ 0.05; bsignificantly different from G2; P ≤ 0.05; and csignificantly different from G3; P ≤ 0.05. G1: untreated control; G2: treated with geraniol; and G3: treated with essential oil.

Figure 5.

Hepatic activities of catalase, SOD, and GSH-Px after 30 days for all experimental groups. Values are given as the mean ± SD for each group of eight animals. aSignificantly different from G1; P ≤ 0.05; bsignificantly different from G2; P ≤ 0.05; and csignificantly different from G3; P ≤ 0.05. G1: untreated control; G2: treated with geraniol; and G3: treated with essential oil.

4. Discussion

EOs are widely used in aromatherapy procedures and there is interest in reports on the hepatic toxicity of these natural products. However, few studies have explored the effects of EOs on an organism when administered by inhalation. Since EOs have been extensively used in aromatherapy due to their therapeutic properties and also used in food products, in dermatology, and in the fragrance and cosmetic industries [14], there is interest in investigating their hepatic toxicity, as well as dyslipidemia.

C. martinii EO reduced the final water intake of the rats, but without altering other parameters that we studied. No significant changes were observed in final body weight, body weight gain, final food intake, or total serum protein level, indicating no dehydration and no deficiencies of nutritionally important compounds in animals in the experimental groups. These results disagree with others studies, which showed that the use of different EOs, for example, Citrus aurantifolia EO, decreases food intake and, consequently, weight gain [28, 29].

There were no changes in serum glucose levels between the groups, indicating maintenance of glycemic homeostasis in these animals. However, other experimental studies have demonstrated that C. martinii extracts exhibit antihyperglycemic activities through inhibition of α-glucosidase under diabetic conditions [30]. Assays with C. citratus aqueous extract (500 mg/kg/day; via oral) showed that the mechanism by which the extract induced hypoglycemia could be attributed to increased insulin synthesis and secretion or increased peripheral glucose utilization [31].

The inhalation of both geraniol (G2) and C. martinii EO (G3) reduced total cholesterol, but no changes in the serum triacylglycerol concentration were observed. Our results are in agreement with the result of Adeneye and Agbaje [31] and Burke et al. [10], who observed hypocholesterolemic effects using an aqueous extract of Cymbopogon citratus by oral administration. This reduction caused by EO can possibly be attributed to inhibition of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl CoA reductase, a key enzyme that regulates hepatic cholesterol synthesis [32, 33], or by reduction in the expression of these enzymes [34]. Yu et al. [35] demonstrated that geraniol inhibited the formation of mevalonate, a metabolic intermediate in the biosynthesis of cholesterol, in hepatomas. On the other hand, the administration of the highest EO dose (100 mg/kg) from Cymbopogon resulted in no change in total serum cholesterol [36].

Our results are also in agreement with Costa et al. [36] about total serum cholesterol; they reported that the biochemical parameters did not change after treatment with Cymbopogon but showed that there was a significant reduction in it (F(4,27) = 3.061; P ≤ 0.05) after the administration of the highest EO dose (100 mg/kg) by gavage over a period of 21 days.

Since urea is formed in the liver and excreted by kidneys, estimation of this nitrogenous compound in the bloodstream is important to estimate both hepatic and renal functions. Animals treated with geraniol and EO did not show altered serum urea levels, suggesting a normal degree of protein catabolism, which was confirmed by a normal concentration of hepatic protein. Although there was no alteration in the levels of serum urea in the G2 group, we cannot exclude the involvement of possible changes in the glomerular filtration rate in these animals. In clinical practice, serum creatinine, a biomarker for renal failure, is used as an indicator of renal function [37]. Curiously, serum creatinine levels were higher in the G2 group and lower in the G3 group, suggesting a decrease in renal excretion and some degree of renal insufficiency or early stages of kidney dysfunction when the major compound of C. martinii EO was administrated alone. The animals treated with both products had a tendency to have decreased levels of serum urea in our study. Serum creatinine was higher in G2, which may indicate lower renal excretion since the creatinine production was relatively constant [38].

Plasma membrane damage from some cells types, such as hepatic cells, is accompanied by release of cytosolic enzymes into bloodstream, a phenomenon that always occurs under several pathophysiological conditions [39]. The aminotransferases ALT and AST are used for diagnosis of hepatic injury after toxic agents exposure [40]. There was a significant increase in serum ALT activity in animals that inhaled geraniol (Figure 3). Since serum enzymatic activity of ALT is often used as a biomarker of hepatic toxicity, we can assume that there was some injury in hepatic tissue induced by geraniol after 30 days.

ROS, such as superoxide anion (O2 −), hydroxyl radicals (OH−), and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), are formed through mitochondrial respiration during normal cellular metabolism. However, the cells have an enzymatic antioxidant defense system against ROS, but, under certain pathological conditions the excess formation of ROS results in suppression of antioxidant enzymes, the increase of ROS can occur in this way leading to oxidative stress [41].

Lipid peroxidation is an important toxic event because involves the removal of hydrogen from fatty acid chains mediated by ROS [42, 43] this way can lead to cell death and tissue damage.

The endogenous antioxidant enzyme includes superoxide dismutase that catalyzes the dismutation of superoxide radicals [23]. Glutathione peroxidase catalyzes the reduction of hydrogen peroxidase to water through the oxidation of reduced glutathione. Catalase also participates in this conversion [44].

Significantly high LH was observed in rats exposed to geraniol (G2), while the beneficial effect of C. martinii EO was evidenced by the reduced LH in these animals. The reductions observed in G3 can be attributed to a synergistic mechanism: a concomitant antioxidant action between other compounds, for example, linalool and β-caryophyllene, present in the C. martinii EO that showed antioxidant activity in other researches [45, 46]. Since free radical scavenger ability depends on the number of hydroxyl radicals in the molecule [43], the inhalation of the total C. martinii EO contributed to the reduction in the formation of ROS.

Rats exposed to geraniol (G2) had higher catalase, SOD, and GSH-Px activities, indicating that antioxidant enzyme activities were not sufficient to inhibit the ROS action and, consequently, the lipoperoxide generation in liver of these animals.

According to Koek et al. [47] the activity of antioxidants enzymes is increased early in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis but tends to decrease with progression of pathogenesis. The activity of the SOD and catalase did not change in the G3 group, while GSH-Px increased in these animals, which showed lower values for LH. Buch et al. [4] observed increases in both SOD and catalase in the brains of rats treated with C. martini EO. Terpenoids, which are important components of EOs, lowered malondialdehyde levels and improved SOD activity in gastric mucosa [48]. Experimental data have shown that terpenoids, which are main components of EOs, are responsible for their antioxidant action [49, 50].

Since lipid hydroperoxide has been widely studied as marker of lipoperoxidation [51], a process that involves removal of hydrogen from fatty acids side chains by ROS, the result is referring to the mixture of compounds present in C. martinii EO (G3) that was effective in controlling oxidative stress and, therefore, lipoperoxidation by reducing the concentration of LH through a mechanism independent of the endogenous antioxidant enzymatic system.

In another study, geraniol reduced lipid peroxidation and inhibited the release of NO, indicating its possible antioxidant potential in inflammatory lung diseases, in which oxidative stress plays key role in these pathogenesis [14]. Moreover, the possible synergism between the compounds present in EOs can influence biological responses [52]. This can explain the results obtained for the G3 group. Thus, the effects we observed could be attributed to a constituent in a smaller proportion or synergism between compounds that are present in the oil [53]. For biological purposes, it is more informative to study the whole oil than some of its components because the concept of synergism appears to be more significant in the research on natural products [2].

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, C. martinii EO and geraniol maintained the glycemia, triacylglycerol protein, and urea levels but decreased cholesterol levels in Wistar rats. The oxidative stress caused by geraniol alone appears to trigger, to some degree, hepatic toxicity, as can be verified by the increase of serum creatinine and ALT. These results suggest that beneficial actions of C. martinii EO on oxidative stress can prevent the toxicity in liver. This proves the possible interactions between geraniol and numerous chemical compounds present in C. martinii EO.

Abbreviations

- C. martinii:

Cymbopogon martinii

- EO:

Essential oil

- EOs:

Essential oils

- ALT:

Alanine aminotransferase

- AST:

Aspartate aminotransferase

- ROS:

Reactive oxygen species

- LH:

Lipid hydroperoxide

- GSH-Px:

Glutathione peroxidase

- SOD:

Superoxide dismutase

- NBT:

Nitroblue-tetrazole.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Sharma P., Sangwan N., Bose S., Sangwan R. Biochemical characteristics of a novel vegetative tissue geraniol acetyltransferase from a monoterpene oil grass (Palmarosa, Cymbopogon martinii var. Motia) leaf. Plant Science. 2013;203:63–73. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2012.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bakkali F., Averbeck S., Averbeck D., Idaomar M. Biological effects of essential oils—a review. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2008;46(2):446–475. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.09.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arruda M., Viana H., Rainha N., et al. Anti-acetylcholinesterase and antioxidant activity of essential oils from Hedychium gardnerianum sheppard ex ker-gawl. Molecules. 2012;17(3):3082–3092. doi: 10.3390/molecules17033082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buch P., Patel V., Ranpariya V., Sheth N., Parmar S. Neuroprotective activity of Cymbopogon martinii against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion-induced oxidative stress in rats. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2012;142(1):35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sinha S., Biswas D., Mukherjee A. Antigenotoxic and antioxidant activities of palmarosa and citronella essential oils. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2011;137(3):1521–1527. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lodhia M. H., Bhatt K. R., Thaker V. S. Antibacterial activity of essential oils from palmarosa, evening primrose, lavender and tuberose. Indian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2009;71(2):134–136. doi: 10.4103/0250-474X.54278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prashara A., Hili P., Veness R. G., Evans C. S. Antimicrobial action of palmarosa oil (Cymbopogon martinii) on Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Phytochemistry. 2003;63(5):569–575. doi: 10.1016/s0031-94220300226-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duarte M. C., Leme E. E., Delarmelina C., Soares A. A., Figueira G. M., Sartoratto A. Activity of essential oils from Brazilian medicinal plants on Escherichia coli . Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2007;111(2):197–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matés J. M., Segura J. A., Alonso F. J., Márquez J. Natural antioxidants: therapeutic prospects for cancer and neurological diseases. Mini-Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry. 2009;9(10):1202–1214. doi: 10.2174/138955709789055180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burke Y., Stark M., Roach S. L., Sen S. E., Crowell P. L. Inhibition of pancreatic cancer growth by the dietary isoprenoids farnesol and geraniol. Lipids. 1997;32(2):151–156. doi: 10.1007/s11745-997-0019-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carnesecchi S., Schneider Y., Ceraline J., et al. Geraniol, a component of plant essential oils, inhibits growth and polyamine biosynthesis in human colon cancer cells. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2001;298(1):197–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen W., Viljoen A. M. Geraniol—a review of a commercially important fragrance material. South African Journal of Botany. 2010;76(4):643–651. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2010.05.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Solórzano-Santos F., Miranda-Novales M. G. Essential oils from aromatic herbs as antimicrobial agents. Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 2012;23(2):136–141. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tiwari M., Kakkar P. Plant derived antioxidants—geraniol and camphene protect rat alveolar macrophages against t-BHP induced oxidative stress. Toxicology in Vitro. 2009;23(2):295–301. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2008.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jimbo D., Kimura Y., Taniguchi M., Inoue M., Urakami K. Effect of aromatherapy on patients with Alzheimer's disease. Psychogeriatrics. 2009;9(4):173–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-8301.2009.00299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buchbauer G., Jirovetz L., Jäger W., Dietrich H., Plank C. Aromatherapy: evidence for sedative effects of the essential oil of lavender after inhalation. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung C. 1991;46(11-12):1067–1072. doi: 10.1515/znc-1991-11-1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bagetta G., Morrone L. A., Rombolà L., et al. Neuropharmacology of the essential oil of bergamot. Fitoterapia. 2010;81(6):453–461. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanida M., Niijima A., Shen J., Nakamura T., Nagai K. Olfactory stimulation with scent of essential oil of grapefruit affects autonomic neurotransmission and blood pressure. Brain Research. 2005;1058(1-2):44–55. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maffei M. E., Gertsch J., Appendino G. Plant volatiles: production, function and pharmacology. Natural Product Reports. 2011;28(8):1359–1380. doi: 10.1039/c1np00021g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yousofi A., Daneshmandi S., Soleimani N., Bagheri K., Karimi M. H. Immunomodulatory effect of Parsley (Petroselinum crispum) essential oil on immune cells: mitogen-activated splenocytes and peritoneal macrophages. Immunopharmacology and Immunotoxicology. 2012;34(2):303–308. doi: 10.3109/08923973.2011.603338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inouye S., Takizawa T., Yamaguchi H. Antibacterial activity of essential oils and their major constituents against respiratory tract pathogens by gaseous contact. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2001;47(5):565–573. doi: 10.1093/jac/47.5.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burtis C. A., Ashwood E. R., Bruns D. E. Tietz: Fundamentos de Química Clínica. 6th. Elsevier Editora Ltda; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johansen J. S., Harris A. K., Rychly D. J., Ergul A. Oxidative stress and the use of antioxidants in diabetes: linking basic science to clinical practice. Cardiovascular Diabetology. 2005;4, article 5 doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-4-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matés J. M., Segura J. A., Alonso F. J., Márquez J. Intracellular redox status and oxidative stress: implications for cell proliferation, apoptosis, and carcinogenesis. Archives of Toxicology. 2008;82(5):273–299. doi: 10.1007/s00204-008-0304-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wieckowska A., McCullough A. J., Feldstein A. E. Noninvasive diagnosis and monitoring of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: present and future. Hepatology. 2007;46(2):582–589. doi: 10.1002/hep.21768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muriel P. Role of free radicals in liver diseases. Hepatology International. 2009;3(4):526–536. doi: 10.1007/s12072-009-9158-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Almeida R. N., Motta S. C., Faturi C. D. B., Catallani B., Leite J. R. Anxiolytic-like effects of rose oil inhalation on the elevated plus-maze test in rats. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2004;77(2):361–364. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brenes A., Roura E. Essential oils in poultry nutrition: main effects and modes of action. Animal Feed Science and Technology. 2010;158(1-2):1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2010.03.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Asnaashari S., Delazar A., Habibi B., et al. Essential oil from Citrus aurantifolia prevents ketotifen-induced weight-gain in mice. Phytotherapy Research. 2010;24(12):1893–1897. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ghadyale V., Takalikar S., Haldavnekar V., Arvindekar A. Effective control of postprandial glucose level through inhibition of intestinal alpha glucosidase by Cymbopogon martinii (Roxb.) Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/372909.372909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adeneye A. A., Agbaje E. O. Hypoglycemic and hypolipidemic effects of fresh leaf aqueous extract of Cymbopogon citratus Stapf. in rats. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2007;112(3):440–444. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crowell P. L. Prevention and therapy of cancer by dietary monoterpenes. Journal of Nutrition. 1999;129(3):775S–778S. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.3.775S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu P., Schrag M. L., Slaughter D. E., Raab C. E., Shou M., Rodrigues A. D. Mechanism-based inhibition of human liver microsomal cytochrome P450 1A2 by zileuton, A 5-lipoxygenase inhibitor. Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 2003;31(11):1352–1360. doi: 10.1124/dmd.31.11.1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cho S.-Y., Jun H.-J., Lee J. H., Jia Y., Kim K. H., Lee S.-J. Linalool reduces the expression of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl CoA reductase via sterol regulatory element binding protein-2- and ubiquitin-dependent mechanisms. FEBS Letters. 2011;585(20):3289–3296. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu S. G., Hildebrandt L. A., Elson C. E. Geraniol, an inhibitor of mevalonate biosynthesis, suppresses the growth of hepatomas and melanomas transplanted to rats and mice. Journal of Nutrition. 1995;125(11):2763–2767. doi: 10.1093/jn/125.11.2763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Costa C., Bidinotto L. T., Takahira R. K., Salvadori D. M. F., Barbisan L. F., Costa M. Cholesterol reduction and lack of genotoxic or toxic effects in mice after repeated 21-day oral intake of lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus) essential oil. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2011;49(9):2268–2272. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2011.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perrone R. D., Madias N. E., Levey A. S. Serum creatinine as an index of renal function: new insights into old concepts. Clinical Chemistry. 1992;38(10):1933–1953. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heymsfield S. B., Arteaga C., McManus C. M., Smith J., Moffitt S. Measurement of muscle mass in humans: validity of the 24-hour urinary creatinine method. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1983;37(3):478–494. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/37.3.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang R.-Z., Park S., Reagan W. J., et al. Alanine aminotransferase isoenzymes: molecular cloning and quantitative analysis of tissue expression in rats and serum elevation in liver toxicity. Hepatology. 2009;49(2):598–607. doi: 10.1002/hep.22657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ozer J., Ratner M., Shaw M., Bailey W., Schomaker S. The current state of serum biomarkers of hepatotoxicity. Toxicology. 2008;245(3):194–205. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2007.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Halliwell B. Antioxidants in human health and disease. Annual Review of Nutrition. 1996;16:33–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.16.070196.000341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abuja P. M., Albertini R. Methods for monitoring oxidative stress, lipid peroxidation and oxidation resistance of lipoproteins. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2001;306(1-2):1–17. doi: 10.1016/S0009-8981(01)00393-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Faine L. A., Rodrigues H. G., Galhardi C. M., et al. Effects of olive oil and its minor constituents on serum lipids, oxidative stress, and energy metabolism in cardiac muscle. Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 2006;84(2):239–245. doi: 10.1139/y05-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Preiser J.-C. Oxidative stress. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. 2012;36(2):147–154. doi: 10.1177/0148607111434963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jana S., Patra K., Sarkar S., et al. Antitumorigenic potential of linalool is accompanied by modulation of oxidative stress: an in vivo study in sarcoma-180 solid tumor model. Nutrition and Cancer. 2014;66:835–848. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2014.904906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Calleja M. A., Vieites J. M., Montero-Melendez T., Torres M. I., Faus M. J., Gil A., Suarez A., Calleja M. A. The antioxidant effect of beta-caryophyllene protects rat liver from carbon tetrachloride-induced fibrosis by inhibiting hepatic stellate cell activation. British Journal of Nutrition. 2013;109:394–401. doi: 10.1017/S0007114512001298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koek G. H., Liedorp P. R., Bast A. The role of oxidative stress in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2011;412(15-16):1297–1305. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2011.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rocha N., de Oliveira G., de Araújo F. Y., et al. (-)-α-Bisabolol-induced gastroprotection is associated with reduction in lipid peroxidation, superoxide dismutase activity and neutrophil migration. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2011;44(4):455–461. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2011.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fadel H., Marx F., El-Sawy A., El-Ghorab A. Effect of extraction techniques on the chemical composition and antioxidant activity of Eucalyptus camaldulensis var. brevirostris leaf oils. Zeitschrift für Lebensmitteluntersuchung und -Forschung A. 1999;208(3):212–216. doi: 10.1007/s002170050405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grassmann J., Litwack G. Terpenoids as plant antioxidants. Plant Hormones. 2005;72:505–535. doi: 10.1016/S0083-6729(05)72015-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nageswari K., Banerjee R., Menon V. P. Effect of saturated, ω-3 and ω-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids on myocardial infarction. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry. 1999;10(6):338–344. doi: 10.1016/s0955-28639900007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gershenzon J., Dudareva N. The function of terpene natural products in the natural world. Nature Chemical Biology. 2007;3(7):408–414. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Houghton P. J., Howes M.-J., Lee C. C., Steventon G. Uses and abuses of in vitro tests in ethnopharmacology: visualizing an elephant. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2007;110(3):391–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]