Abstract

The United States (U.S.) food system is primarily an economic enterprise, with far-reaching health, environmental, and social effects. A key data source for evaluating the many effects of the food system, including the overall quality and extent to which it provides the basic elements of a healthful diet, is the Food Availability Data System. The objective of the present study was to update earlier research that evaluated the extent to which the U.S. food supply aligns with the most recent Federal dietary guidance, using the current Healthy Eating Index (HEI)-2010 and food supply data extending through 2010. The HEI-2010 was applied to 40 years of food supply data (1970–2010) to examine trends in the overall food supply as well as specific components related to a healthy diet, such as fruits and vegetables. The HEI-2010 overall summary score hovered around half of optimal for all years evaluated, with an increase from 48 points in 1970 to 55 points (out of a possible 100 points) in 2010. Fluctuations in scores for most individual components did not lead to sustained trends. The present study continues to demonstrate sizable gaps between Federal dietary guidance and the food supply. This disconnect is troublesome within a context of high rates of diet-related chronic diseases among the population and suggests the need for continual monitoring of the quality of the food supply. Moving toward a food system that is more conducive to healthy eating requires consideration of a range of factors that influence food supply and demand.

Keywords: food supply, food availability, diet quality, Healthy Eating Index, food systems

INTRODUCTION

The United States (U.S.) food system is primarily an economic enterprise, driven by factors such as trade, costs, prices, and demand,1 with far-reaching health, environmental, and social effects. A key source of data for evaluating the many effects of the U.S. food system is the national Food Availability Data System.2 Food availability data represent the sum total of food that enters retail distribution channels and are calculated for each year by summing production, imports, and past-year stores and subtracting exports and current-year stores—herein referred to as “the food supply.” Traditionally, these data have been used to examine the capacity of a country’s food supply to meet the nutritional needs of its people, examine trends in food supplies over time, monitor food insecurity, project future trends in food insecurity, and guide food and agricultural policy.2,3

The extent to which the food system provides the basic elements of a healthful diet is a critical consideration in evaluating its merit given the relationship between diet and health. The federal government’s policy on what constitutes a healthy diet is enumerated every five years in the Dietary Guidelines for Americans.4–10 The key principles have remained relatively stable since the first set of Guidelines in 1980, with updates and refinements to guidance reflecting nuances rather than dramatic shifts in the evidence base. The core tenets of a healthy diet have consistently included an emphasis on fruits and vegetables, and moderation in consumption of sodium, saturated fats, and added sugars.

Earlier research11 examined the healthfulness of the U.S. food supply from 1970 through 2007 using the Healthy Eating Index (HEI)-2005, a density-based diet quality index that assesses conformance with the 2005 Dietary Guidelines. Since this previous work, which noted sizable gaps between Federal dietary guidance and the food supply, both the HEI and the food supply data have been updated.2,12 The HEI-2010 reflects the evolution of, and nuances in, the guidance provided by the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans4 compared to the prior set of Guidelines, including the recommendations to consume less saturated fatty acids by replacing them with mono- and polyunsaturated fatty acids, limit refined grains, and emphasize seafood and plant proteins. Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to update earlier research that evaluated the extent to which the U.S. food supply aligns with the most recent Federal dietary guidance, using the current HEI and food supply data extending through 2010.

METHODS

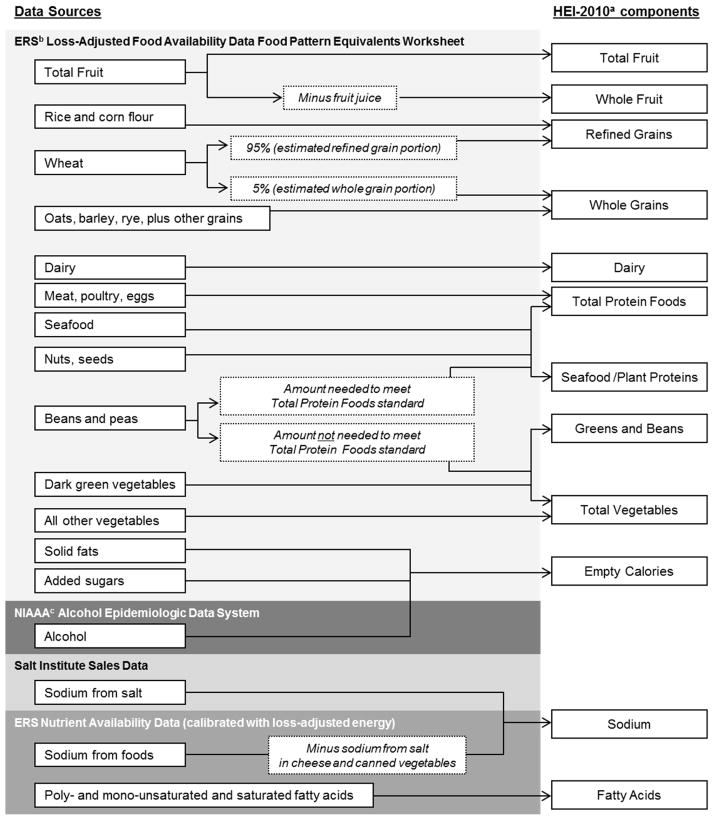

HEI-2010 scores were calculated for the years 1970–2010 using publicly available datasets that provide the best estimates of the food supply as of January 2013. The calculations required to generate scores for each HEI-2010 component are shown in Figure 1. The study was not subject to institutional review board review as all data were from existing, publicly available sources and no original research involving human subjects was conducted.

Figure 1.

Data sources used and calculations required to generate scores for the HEI-2010 components. All components except Fatty Acids are expressed relative to energy, which is derived by combining total energy from the Loss-Adjusted Food Availability Data with energy from alcoholic beverages. For Whole Grains, 0.6 oz was added to the sum of whole grains because this amount is unaccounted for in the ERS food supply data each year. Solid fat is calculated by subtracting salad and cooking oil from the sum of total added fats, oils, and dairy fats. Fatty Acids is the ratio of polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fatty acids over saturated fatty acids.

aHEI = Healthy Eating Index

bERS = Economic Research Service of the United States Department of Agriculture

cNIAAA = National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism

Healthy Eating Index-2010

The HEI-2010 has 12 components,12 nine of which assess adequacy (Total Fruit, Whole Fruits, Total Vegetables, Greens and Beans, Whole Grains, Dairy, Total Protein Foods, Seafood and Plant Proteins, and Fatty Acids) and three of which capture moderation (Refined Grains, Sodium, and Empty Calories). The minimum score for all components is zero, whereas the maximum score varies between five, 10, and 20. Details regarding the development and scoring of the HEI-2010 have been published previously12 and can be found in a technical report and fact sheet provided by the United States Department of Agriculture.13

Data Sources

Four datasets were drawn upon for this analysis. These included two obtained from the United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service (ERS), including the Loss-Adjusted Food Availability Data (LAFAD) and ERS Nutrient Availability Data (NAD).2 The LAFAD, which account for losses due to food spoilage and waste, provide daily per capita quantities in units that align with current dietary guidance. The NAD include the estimated non-loss-adjusted nutrient content of the food available for domestic consumption. The data available from ERS include only a portion of the sodium in the food supply: naturally occurring sodium and that from salt found in canned vegetables and cheese. Therefore, data on salt sold for human consumption were obtained from the Salt Institute14 (a North American non-profit trade association); these estimates include salt used in processing, cooking, and at the table. Estimates of per capita alcohol consumption (derived from annual alcohol sales data) were obtained from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) Alcohol Epidemiologic Data System.15

Data required for nine of the 12 components, plus two of the Empty Calories subcomponents (i.e., added sugars and solid fat), were available through 2010 from the LAFAD. For the remaining components (Sodium, Fatty Acids, and the alcohol subcomponent of Empty Calories), it was necessary to draw upon the remaining databases and to perform imputation for the most recent years. The NAD provide estimates through 2006; values for sodium (in cheese and canned vegetables) and fatty acids were ascribed for 2007–2010 by carrying forward the ratio of each respective nutrient to total calories from 2006 and applying it to the total calories from the LAFAD in 2007, 2008, 2009, or 2010. Salt values for 2008–2010 were also imputed. Given an observed decrease in the salt supply from 2005 to 2007, a continued downward trend was assumed and the average annual percentage decline starting in 2005 (1.65%) was used to generate values of sodium from salt for 2008 through 2010. The 2009 alcohol values were attributed to 2010 as the supply of alcohol has remained stable since 1970.

Calculations

Total daily per capita cup or ounce equivalents of the foods required to calculate quantities of the following components were obtained from the LAFAD: Total Fruit, Whole Fruit, Refined Grains, Whole Grains, Dairy, Total Protein Foods, Seafood and Plant Proteins, Greens and Beans, and Total Vegetables. Most calculations required summing or subtracting certain foods to calculate each component (further details are available in Figure 1 and at http://appliedresearch.cancer.gov/tools/hei/tools.html). To calculate Whole Grains, 5% of wheat flour—the portion considered to be whole wheat (personal communication, Cynthia Harriman, Whole Grains Council, 2012)—was added to the sum of total oat, barley, and rye, plus 0.6 ounces (the amount of unreported whole grains per capita per day in the food supply according to the ERS).16 Grams of solid fats and added sugars also were obtained from the LAFAD for the calculation of Empty Calories.

The NAD were used to obtain values for sodium and saturated, polyunsaturated, monounsaturated fatty acids. Because loss-adjusted nutrient data were unavailable for these nutrients, the unadjusted values were calibrated by multiplying by the total loss-adjusted calories for the given year from LAFAD and dividing by the total unadjusted calories from the NAD for that year. To calculate the alcohol subcomponent of Empty Calories, annual gallons of ethanol from beer, wine, and liquor were obtained from the NIAAA and converted to grams of ethanol per capita per day.

For the Sodium component, the calibrated value based on the NAD was considered in conjunction with the Salt Institute Sales Data. These data include annual tons of salt sold for human consumption, which were converted to mg of sodium per capita per day. To avoid double counting the sodium from salt added during the canning of vegetables and the processing of milk to cheese, the NAD estimates were adjusted to remove sodium from these sources. Subsequently, the remaining intrinsic sodium from the NAD and the sodium from the Salt Institute Sales Data were summed and used to calculate the Sodium component.

To estimate energy in the food supply, total calories from the LAFAD were combined with calories from alcoholic beverages from the NIAAA.

The ratio of each dietary component to energy, or the ratio of polyunsaturated and monounsaturated to saturated fatty acids, was calculated. The resulting value was then compared to the standard established for the respective component, and the component and total HEI-2010 scores determined. SAS code for deriving HEI-2010 scores that can be applied to food supply data are available at http://appliedresearch.cancer.gov/tools/hei/tools.html.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

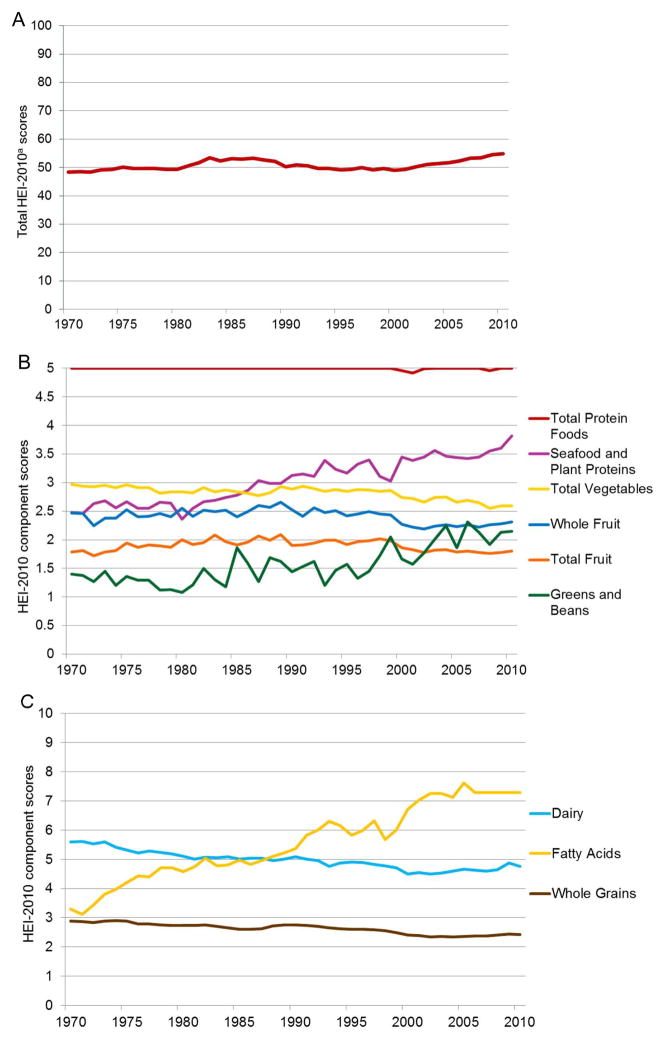

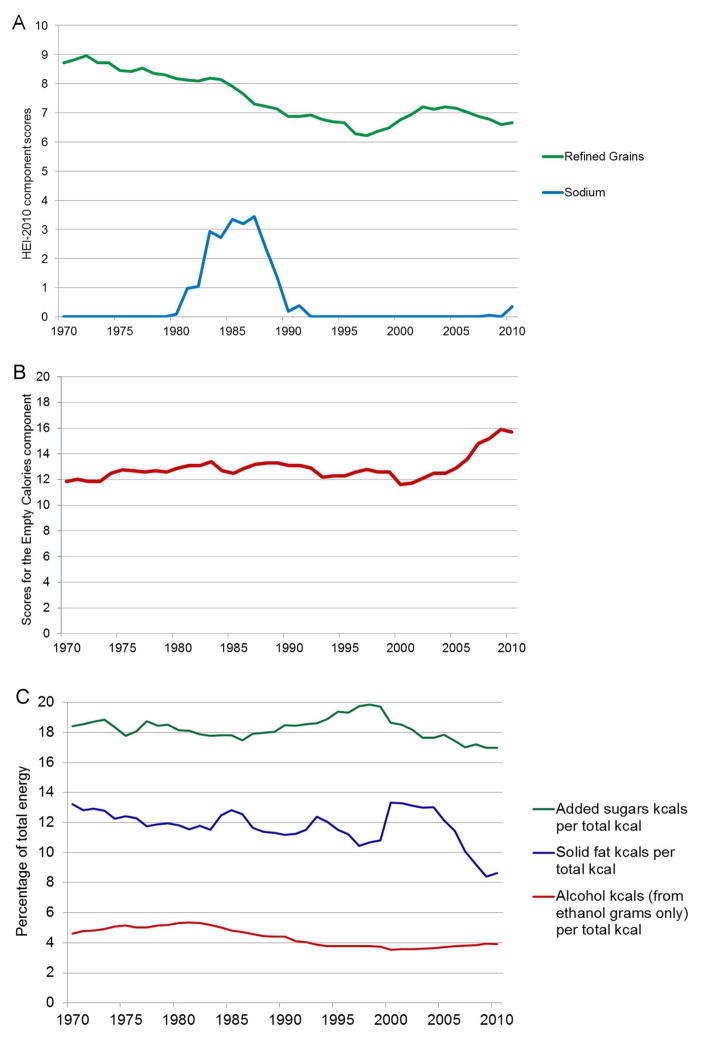

The present study indicates that the quality of the U.S. food supply is not aligned with Federal dietary guidance. Although the key principles espoused by the Dietary Guidelines have remained relatively stable over time, the summary HEI-2010 score for the food supply hovered around half of optimal (100 points) for all years (Figure 2A). This finding is consistent with data on individual dietary intakes of Americans, which show that HEI-2010 scores have remained close to 50 for all years evaluated (51.9 in 2001–2002 and 53.5 in 2007–2008).17 In evaluating whether changes over time are meaningful, an effect size of 0.5 (i.e., half a standard deviation) is often considered to be moderate.18 According to prior analyses of U.S. population dietary intake data, the standard deviation for HEI-2010 scores is 11 to 12 points (unpublished data, 2014). This indicates that a change of 5 or 6 points could be considered moderate and thus, that the seven point increase observed in the overall HEI-2010 score from 1970 to 2010 is meaningful. The trends in scores for individual adequacy components measured on 5- or 10-point scales are shown in Figures 2B and 2C, respectively, and trends in scores for individual moderation components measured on 10- or 20-point scales are shown in Figures 3A and 3B, respectively. The percentage of total calories from each of the Empty Calories subcomponents (i.e., added sugars, solid fat, and alcohol) is shown in Figure 3C. The component that fared best was Total Protein Foods as the food supply consistently provided the recommended amount (or close to it) for all years. Fluctuations in scores for many of the other individual components were apparent, but most were not sustained trends. Scores for Total Fruit, Whole Fruit, Total Vegetables, Greens and Beans, Whole Grains, Dairy, and Sodium remained around or below half of optimal for most years. Although a transient increase to around 3 out of 10 in the mid- to late-1980s occurred for Sodium, the values were at the lowest possible value (indicating excess amounts relative to energy) for most years. The transient increase may reflect a temporary response by the food industry to reduce the sodium in the food supply; however, by 1992, the Sodium score returned to zero.

Figure 2.

Quality of the United States food supply with regard to (A) total HEI-2010 scores, (B) individual HEI-2010 adequacy components measured on a 5-point scale, and (C) individual HEI-2010 adequacy components measured on a 10-point scale, 1970–2010. Dairy includes calcium-fortified dairy alternatives. Fatty Acids is the ratio of polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fatty acids over saturated fatty acids.

aHEI = Healthy Eating Index

Figure 3.

Quality of the United States food supply with regard to (A) individual HEI-2010 moderation components measured on a 10-point scale and (B) Empty Calories measured on a 20-point scale, as well as (C) the percentage of total energy from each subcomponent of Empty Calories (added sugars, solid fat, and alcohol), 1970–2010. For Refined Grains and Sodium, scores rise with decreasing supplies per 1000 kcal. Scores for Empty Calories rise with decreasing percentages of total energy from added sugars, solid fat, and alcohol.

Improvements in scores for Seafood and Plant Protein, Empty Calories, and Fatty Acids were observed. These findings highlight the need for continual monitoring of the food supply to evaluate whether these potentially promising trends persist in future years. Scores for Fatty Acids increased 4 points on a 10-point scale over 40 years. Further examination into the supplies of the different types of fatty acids revealed that this increase in scores was from a small reduction in the supply of saturated fat coupled with a larger increase in the supply of unsaturated fats. Scores for Empty Calories remained between 11.6 and 13.4 until the year 2000, after which scores increased to 15.7 out of a possible 20 points. Investigation of the individual subcomponents of Empty Calories showed that the percentage of calories from solid fat, and to a lesser extent added sugars, decreased from 2000 to 2010, while the percentage of calories from alcohol remained fairly constant. These variations may reflect a response by the food industry to reduce the trans fat, saturated fat, and added sugars in the food supply; however, given the numerous transient changes in scores over the years, caution is warranted in assuming these upward trends will continue rather than plateau or start to trend downward as seen in the past.

A key purpose of this country’s food availability data is to monitor the potential of its food supply to meet the nutritional needs of the population, and presumably, take corrective steps if found lacking. Various studies have been conducted to evaluate either the quality or relative quantity of specific foods over time, some of which have pointed to actions that might afford a healthier food supply.11,19–21 Recommended actions include changes in the type and quantity of food produced; modifications in where and how food is produced; and adjustments in agricultural production, trade, prices, non-food uses, and crop acreage dedicated to food and feed.

Identifying clear directions for change to make the food supply and the broader food system more amenable to healthy eating is complicated by the web of factors that influence food supply and demand.22 Recent efforts to bring together a wider range of perspectives on the food system may help to address this challenge. For example, the Institute of Medicine has convened a committee to develop a framework to guide the assessment of the health, environmental, and social effects of the food system.23 This initiative and similar ones have the potential to guide decision making about food and agricultural policy, marketing, and related factors, with the eventual goal of bringing about a food system that is healthy and sustainable.

This study evaluated the quality of the U.S. food supply using the HEI-2010 and the best available food supply data. Given the study objectives, the use of loss-adjusted food supply data is a notable strength, as many countries do not have such data. In addition, the methods used to collect the data used in this study have remained stable over the years.2,15 There are also several limitations, including the imputation of the most recent values for fatty acids and sodium, salt used in processing, and alcohol, which increases the uncertainty of the findings. It also should be noted that aggregate food supply data do not provide direct measures of actual human consumption, and do not account for demographic factors such as age and sex; therefore, inferences regarding individual consumption cannot be drawn. However, the objective of this study was not to evaluate individual level dietary intake, but rather the quality of the foods that enter retail distribution channels and are available for consumption by individuals.

Conclusions

This study updates earlier research that evaluated the extent to which the U.S. food supply aligns with the most recent Federal dietary guidance, using the current HEI and food supply data extending through 2010. This report demonstrates sizable gaps between Federal dietary guidance and the U.S. food supply over a 40 year period, extending the trends identified earlier, and suggesting that the issues identified using the HEI-2005 are also apparent with the application of the HEI-2010. The identified disconnects are troublesome within a context of high rates of diet-related problems, and presents a challenge for dietitians working toward behavioral changes, as accumulating evidence suggests that individual-level behavior changes are not easily achieved nor maintained within the context of environments that do not facilitate and support them. The gaps observed highlight the need for continual monitoring of the food supply, speaking to the importance of continued collection of the databases that enabled this and similar analyses. Moving toward a food system that is more conducive to healthy eating requires consideration of a range of factors that influence food supply and demand, as well as environmental sustainability. Recent efforts to bring together various perspectives on the food system may shed insights into promising future directions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Lisa Kahle (Information Management Services, Inc.) for her data programming and analysis support; Jeanine Bentley [Economic Research Service of the United States Department of Agriculture] for generously sharing her expertise regarding the Food Availability Data System; and Claire Bosire (Harvard School of Public Health) for providing valuable documentation to assist in the calculation of scores using the various data sources.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest Form

The authors have no conflicts of interest, including no specific financial interests, no relationships, and no affiliations relevant to the subject of our manuscript.

Funding/Support Disclosure

This research was supported by the Cancer Prevention Fellowship Program and the Intramural Research Program, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Paige E Miller, Email: paige.miller@va.gov, Cancer Prevention Fellow (affiliation when primary contribution to the research was made), Cancer Prevention Fellowship Program, National Cancer Institute, 9609 Medical Center Drive 3E418, Rockville, MD, 20850. Dietitian (current affiliation), Nutrition and Food Service, Edward Hines, Jr. VA Hospital, 5000 South 5th Avenue, Hines, IL 60141, Phone: 708-202-8387 x 23442, FAX: 708-202-7998.

Jill Reedy, Email: reedyj@mail.nih.gov, Nutritionist, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute, 9609 Medical Center Drive 3E418, Rockville, MD, 20850, Phone: 240-276-6812, FAX: 240-276-7906.

Sharon I Kirkpatrick, Email: sharon.kirkpatrick@uwaterloo.ca, Assistant Professor, School of Public Health and Health Systems, University of Waterloo, 200 University Avenue West, BMH 1036, Waterloo, ON, Canada N2L 3G1, Phone: 519-888-4567 x37054.

Susan M Krebs-Smith, Email: krebssms@mail.nih.gov, Chief of the Risk Factor Monitoring and Methods Branch, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute, 9609 Medical Center Drive, 3E418, Rockville, MD 20850, Phone: 240-276-6949, FAX: 240-276-7906.

References

- 1.Kinsey JD. The new food economy: consumers, farms, pharms, and science. Journal of Agricultural Economics. 2001;83(5):1113–1130. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture. [Accessed January 20, 2014];Food Availability (Per Capita) Data System. http://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/food-availability-%28per-capita%29-data-system.aspx. Updated December 18, 2013.

- 3.Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. Food Balance Sheets: A Handbook. FAO Corporate Document Repository; Rome, Italy: [Accessed April 27, 2014]. ftp://ftp.fao.org/docrep/fao/011/x9892e/x9892e00.pdf. Published 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010. 7. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Nutrition and Your Health: Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 6.U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Nutrition and Your Health: Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 2. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 7.U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Nutrition and Your Health: Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 3. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 8.U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Nutrition and Your Health: Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 4. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Nutrition and Your Health: Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 5. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 10.U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2005. 6. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krebs-Smith SM, Reedy J, Bosire C. Healthfulness of the U.S. food supply: little improvement despite decades of dietary guidance. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(5):472–477. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guenther PM, Casavale KO, Reedy J, et al. Update of the Healthy Eating Index: HEI-2010. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113(4):569–580. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.U.S. Department of Agriculture. [Accessed April 27, 2014];Healthy Eating Index. http://www.cnpp.usda.gov/healthyeatingindex.htm. Updated December 11, 2013.

- 14.Salt Institute. US Salt Production/Sales. [Accessed June 11, 2009];Facts and Figures for Human Nutrition. http://www.saltinstitute.org/

- 15.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Accessed April 27, 2014];Apparent per Capita Alcohol Consumption: National, State, and Regional Trends. 1977–2009 http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Surveillance92/CONS09.pdf. Published August, 2011.

- 16.Wells HF, Buzby JC. Economic Information Bulletin No. 33. Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture; [Accessed April 27, 2014]. Dietary assessment of major trends U.S. food consumption, 1970–2005. http://www.ers.usda.gov/media/210681/eib33_1_.pdf. Published March 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guenther PM, Casavale KO, Kirkpatrick SI, et al. Nutrition Insight. Vol. 51. U.S. Department of Agriculture; [Accessed April 27, 2014]. Diet quality of Americans in 2001–02 and 2007–08 as measured by the Healthy Eating Index-2010. http://www.cnpp.usda.gov/nutritioninsights.htm. Published April 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis in the Behavioral Sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buzby JC, Wells HF, Vocke G. Economic Research Report. Vol. 31. Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture; [Accessed April 27, 2014]. Possible implications for US agriculture from adoption of select Dietary Guidelines. http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/err-economic-research-report/err31.aspx#.Uug6-bTnal4. Published November 2006. Updated August 6, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.McNamara PE, Ranney CK, Kantor LS, Krebs-Smith SM. The gap between food intakes and the Pyramid recommendations: measurement and food system ramifications. Food Policy. 1999;24(2–3):117–133. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Young CE, Kantor LS. Agriculture Economic Report No. 779. Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture; [Accessed April 27, 2014]. Moving toward the Food Guide Pyramid: Implications for U.S. agriculture. http://webarchives.cdlib.org/sw12j6951w/http://www.ers.usda.gov/Publications/AER779/. Published July 2, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trostle R. Global agricultural supply and demand: factors contributing to the recent increase in food commodity prices. Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture; [Accessed April 27, 2014]. WRS-0801. http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/wrs-international-agriculture-and-trade-outlook/wrs-0801.aspx#.Uug-WLTnal4. Published May 2008. Updated May 28, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Institute of Medicine. [Accessed April 27, 2014];A Framework for Assessing the Health, Environmental, and Social Effects of the Food System. http://www.iom.edu/Activities/Nutrition/AssessingFoodSystem.aspx. Published July 16, 2013.