Abstract

Although often beneficial in the treatment of head and neck cancer (HNC), radiation therapy (XRT) leads to the depletion of vascular supply and eventually decreased perfusion of the tissue. Specifically, previous studies have demonstrated the depletion of vessel volume fraction (VVF) and vessel thickness (VT) associated with XRT. Amifostine (AMF) provides protection from the detrimental effects of radiation damage, allowing for reliable post-irradiation fracture healing in the murine mandible. The purpose of this study is to investigate the prophylactic ability of AMF to protect the vascular network in an irradiated field. Sprague-Dawley rats (n=17) were divided into 3 groups: control (C, n=5), radiated (XRT, n=7), and radiated mandibles treated with Amifostine (AMF XRT, n=5). Both groups receiving radiation underwent a previously established, human equivalent dose of XRT totaling 35 Gray, equally fractionated over 5 days. The AMF XRT group received a weight dependent (0.5mg AMF/5g body weight) subcutaneous injection of AMF 45 minutes prior to XRT. Following a 56-day recovery period, mandibles were perfused, dissected, and imaged with µCT. ANOVA was used for comparisons between groups and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Stereologic analysis demonstrated a significant and quantifiable restoration of VT in AMF treated mandibles as compared to those treated with radiation alone (0.061±.011mm versus 0.042±0.004mm, p=0.027). Interestingly, further analysis demonstrated no significant difference in VT between control mandibles and those treated with AMF (0.067±0.016mm versus 0.061±0.011mm, p=0.633). AMF treatment also showed an increase in VVF, however those results were not statistically significant from VVF values demonstrated by the XRT group. Our data support the contention that AMF therapy acts prophylactically to protect vessel thickness, as AMF-treated mandibles demonstrate VT levels that are not statistically different from controls in the setting of irradiation. Based on these findings, we support the continued investigation of this treatment paradigm in its potential translation for the prevention of vascular depletion after radiotherapy.

Introduction

Head and neck cancer (HNC) and its associated complications will account for 53,000 new cases and 13,000 deaths in 2013 (1). The current standard of care for cancer of this nature often includes operative resection, subsequent reconstruction, and adjuvant radiotherapy. Although often beneficial in the clinical management of HNC, a number of previous studies demonstrated that radiotherapy leads to decreased regenerate vascularity and cellularity, resulting in unacceptably high rates of reconstructive sequelae (2–5). Additionally, ischemia and hypovascularity as a result of radiation therapy (6) predisposes patients to the devastating complications of osteoradionecrosis, pathologic fracture, and non-union (7, 8). Thus, a means to prevent these pathologies would be highly desirable.

Amifostine (AMF) is an organic thiophosphate prodrug under investigation for its cytoprotective capabilities in the setting of XRT. As a result of dephosphorylation in vivo, AMF becomes active as WR-1065. AMF acts as a cellular antioxidant, scavenging radiation-induced free oxygen species that damage local vascularity and tissue (9, 10). Moreover, activated AMF neutralizes reactive metabolites of platinum and alkylating agents and functions as a stabilizer of the global tumor suppressor, p53. In a recent phase III trial, AMF reduced the incidence of xerostomia in patients undergoing radiotherapy for head and neck cancer (9). Our model seeks to build upon these results in soft tissue by further investigating the effects of AMF in bone.

In previous studies, AMF demonstrated selective protection of normal, non-cancerous tissue, which is attributed to higher alkaline phosphatase activity, higher pH, and vascular permeation of normal tissues. Additionally, when treated with AMF prior to radiation, no changes in cancer reoccurrence rates are seen (8–10). This characteristic is of utmost importance in regards to the clinical applicability of AMF to protect and preserve local vascular supply in an irradiated field. Previous work in our laboratory demonstrated this effect as it relates to bone regeneration in both our irradiated models of distraction osteogensis and pathologic fracture (11–19). In this study, we sought to investigate the radio-protective potential of AMF by examining the extent to which it protects the vascular supply in the murine mandible in normal, un-injured bone. The specific aim of this report is to determine the detailed pattern of vascular damage engendered by radiation in the mandible and in so doing help to better understand the pathologic mechanism of radiation injury to the vascular system. Furthermore we aim to determine the efficacy of AMF to protect the bony vasculature from the harmful effects of radiation. We hypothesize that AMF will act prophylactically to protect vascularity thereby potentially reduce the costly occurrence of osteoradionecrosis, pathologic fracture, and the other consequences of hypovascularity associated with radiation therapy.

Materials and Methods

Animal experimentation was conducted in accordance with the guidelines published in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals: Eighth Edition. Animal protocol # PRO00001267 was approved by the University of Michigan’s Committee for the Utilization and Care of Animals (UCUCA) prior to implementation

Experiment Outline

Sprague-Dawley rats (n=17) were divided into 3 groups: control (C), radiated (XRT), and radiated mandibles with cytoprotective AMF treatment (AMF XRT). Both radiation groups received a previously established fractionated dose of 7 Gy/day for 5 days (35 Gy total), equivalent to a human dose of 70 Gy (20, 21). Following a 56-day recovery period, mandibles were perfused with Microfil, dissected, and imaged with µCT.

Amifostine Procedure

A subcutaneous injection of AMF (0.5ml AMF/5g body weight) was given 45 minutes prior to each fractionated dose of radiation therapy once daily for five consecutive days according to the radiation therapy schedule outlined below. The dosing schedule of AMF was derived from an extensive review of the literature and was further optimized for use in this animal model (10, 22–24).

Radiation

Rat hemimandibles were irradiated using a Philips RT250 orthovoltage unit (250 kV, 15 mA) (Kimtron Medical), fractionating the dose at 7 gray per day over 5 days, for a 35 Gray total, in the Irradiation Core at the University of Michigan Cancer Center (20, 21). Rats were anesthetized using an Isofluorane/Oxygen mixture (2% and 1 L/min), and placed right side down, exposing only the left hemimandible to radiation therapy. A lead shield with a rectangular window protected the pharynx, brain, and the remainder of the animal. This radiation protocol has been performed for several years in the department of Radiation Oncology under ULAM/UCUCA-approved protocols. The rats were maintained on regular chow and water throughout the duration of their 56-day recovery period.

Perfusion Protocol

All rats were anesthetized prior to thoracotomy and underwent left cardio-ventricular catheterization. Perfusion with heparinized normal saline was followed by pressure fixation with normal buffered formalin (10% NBF) solution, ensuring euthanasia. After fixation, the vasculature was injected with Microfil (MV-122, Flow Tech, Carver, MA). Mandibles were harvested and were subsequently demineralized and fixed using Cal-Ex II (Fisher Scientifics; Fairlawn, NJ), a formic acid/formaldehyde solution. Leeching of mineral was confirmed with serial radiographs to ensure adequate demineralization prior to scanning. Perfusion success was assessed both grossly and subsequently via micro-computed tomography (Micro-CT / µCT) maximal intensity projection (MIP), and any underperfused samples were discarded.

Micro-CT – Vascularity

Specimens were scanned at 18µm voxel size with µCT. We have previously utilized this voxel size and have found it optimal to adequately resolve small murine mandibular vessel networks. The region of interest was defined as a distance measuring 5.1 mm after the third molar in each group. Analysis of the left hemimandible region of interest (ROI) was then performed with MicroView 2.2 software (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI.). Contours were defined by highlighting the regions of interest using the spline function. Analysis of vascularity in this region was accomplished by setting a global Grayscale threshold of 1000 to differentiate vessels from surrounding tissue as previously described. Using this information, MicroView allocated only the number of voxels above this threshold and used stereologic algorithms to assign relative densities to the voxels based on the contrast content within the vessels. The ROI was analyzed for vessel thickness, vessel volume fraction, vessel number, and vessel separation. While vessel volume fraction depicts the fraction of bone occupied by the volume of vessels within the ROI tissue, vessel number is a reflection of the actual number of vessels per mm within the ROI. Vessel volume fraction is calculated based on the voxel size and the number of segmented voxels in the 3-D image after application of the binarization threshold. To calculate vessel number, a segmented volume is skeletonized, leaving just the voxels above our binarization threshold at the mid-axes of the vascular structures. The vessel number is defined as the inverse of the mean spacing between the mid-axes of the structures in the segmented volume. Vessel thickness is measured by calculating an average of the local voxel thicknesses within the vessel. Local voxel thickness is defined as the diameter of the largest sphere that both contains the point regardless of position within the sphere and is completely within the structure of interest. This distinguishes the blood vessel from the background space surrounding the object. It is worth noting that vessel thickness, in this case, defines the diameter of the vessel and not the thickness of the vessel wall. In addition, for qualitative comparison, 3-D visualization of vascular anatomy was accomplished utilizing maximal intensity projections (MIPs). This enables instant volume rendering of a volumetric data set yielding a 3-D representation of the scanned specimen.

Statistical Analysis

All data is presented as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics software (SPSS, Chicago, IL). The data were compared using ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc method and two-tailed Students t-test. Levene’s test was used to determine distribution of the data. Significance was assigned as p < 0.05.

Results

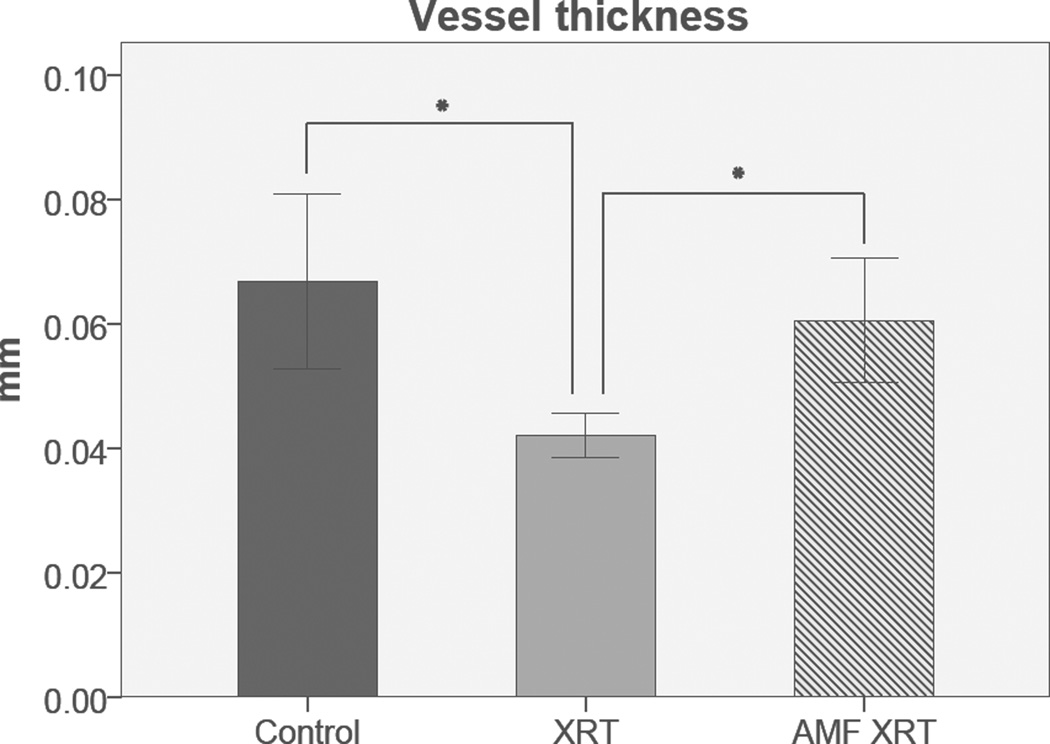

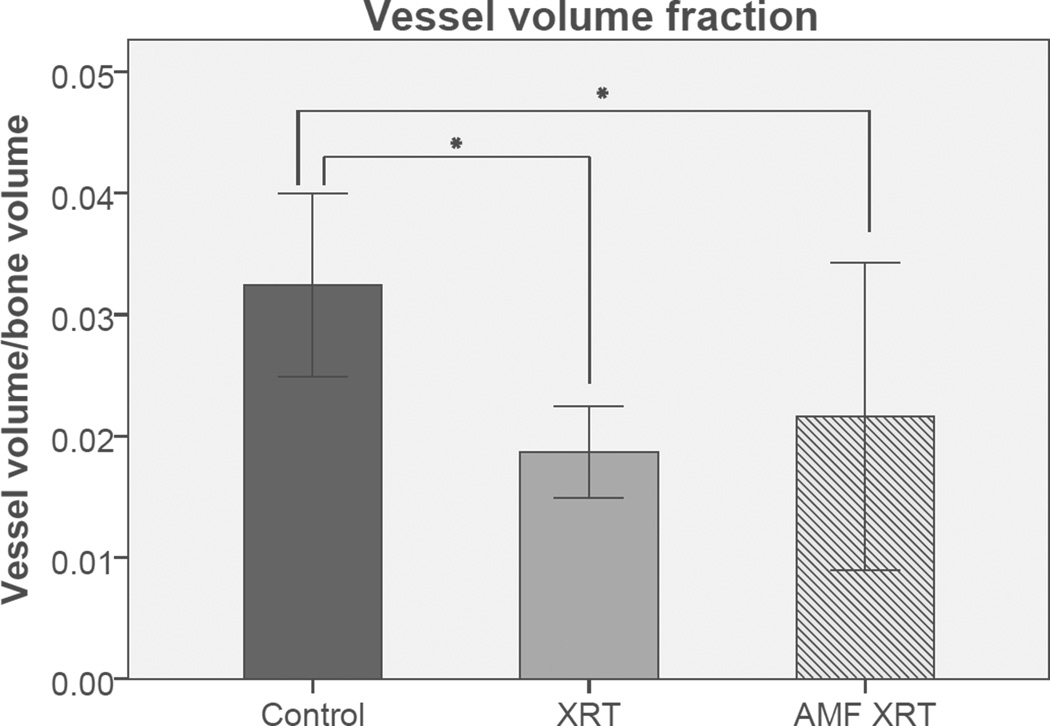

AMF appeared to ameliorate the incidence of radiation-induced alopecia and oral mucositis. All animals underwent successful perfusions, were dissected, decalcified and subjected to subsequent micro-CT scanning. Stereologic analysis and ANOVA demonstrated a significant and quantifiable protection of VT in AMF-treated mandibles as compared to those treated with radiation alone (0.061±0.011mm versus 0.042±0.004mm, p=0.027). Interestingly, further analysis demonstrated no significant difference in VT between control mandibles and those treated with AMF (0.067±0.016mm versus 0.061±0.011mm, p=0.633) (Figure 1). AMF treatment also showed an increase in VVF, however those results were not statistically significant from VVF values demonstrated by the XRT group (Figure 2). VN and VS were not significantly diminished by XRT, and thus did not show significant changes with AMF treatment. These results are summarized in Table I.

Figure 1.

Vessel Thickness: Graphical representation of VT means and standard deviation detailing the efficacy of Amifostine treatment. Asterisk indicates statistical significance. Significance taken at p < 0.05. Error bars denote +/− one standard deviation from the mean.

Figure 2.

Vessel Volume Fraction: Graphical representation of VVF means and standard deviations detailing the efficacy of Amifostine treatment. Asterisk indicates statistical significance. Significance taken at p < 0.05. Error bars denote +/− one standard deviation from the mean.

Table I.

Table depicting VT, VVF, VN, and VS means and comparison p-values between all groups.

| Control(C) | Radiated (XRT) |

Radiated Amifostine (AMF/XRT) |

p-value(C vs. XRT) |

p-value(XRT vs. AMF/XRT) |

p-value(C vs. AMF/XRT) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Vessel Thickness(VT) |

0.0668 | 0.0419 | 0.0605 | 0.004* | 0.027* | 0.633 |

|

Vessel Volume Fraction(VVF) |

0.0324 | 0.0187 | 0.0216 | 0.039* | 0.898 | 0.364 |

|

Vessel Number (VN) |

0.4721 | 0.4486 | 0.3356 | 0.951 | 0.276 | 0.207 |

|

Vessel Separation(VS) |

2.0809 | 2.3270 | 3.4371 | 0.651 | 0.311 | 0.197 |

Asterisk denotes statistical significance. Significance taken at p < 0.05.

Discussion

Pathologic fractures and osteoradionecrosis continue to manifest themselves as damaging consequences of often life-saving radiotherapy. These sequelae can have devastating and life-altering consequences for patients stricken with these conditions, leaving them with the inability to eat, drink, or socialize normally. Here we demonstrated the clinically relevant capability of AMF to protect an essential metric of vascularity, vessel thickness, in the setting of irradiation. Radiation is known to result in hypovascularity, thereby reducing vascular flow and circulation throughout an organism. In fact, we demonstrate in this murine model quite specifically that the vascular damage engendered by radiation affects neither vessel number nor vessel separation, but instead indicates that the pathologic changes instigated by radiation effect mainly the luminal diameter of the blood vessels and to a lesser extent the vessel volume fraction. These findings give a better understanding of the distinctive mechanism of injury to the bony vasculature as a result of radiation injury. Furthermore we demonstrate that the use of prophylactic AMF protects the vascular system from the significant loss of luminal diameter by maintaining the same vessel thickness and caliber as non-radiated controls. This is vital, as it supports normal blood flow through tissues which carry essential nutrients and oxygen to cells. These basic nutrients are responsible for cell growth and development and account for the prevention of cellular necrosis, apoptosis, and hypoplasia.

Although it is true that AMF is not considered angiogenic, and in our study we demonstrate a mechanism more consistent with angioprotection, previous studies have assumed AMF to be anti-angiogenic (25–28). This assumption is highly disputable, as several mechanisms of action regarding the ability of AMF to protect and preserve vascularity have been presented in recent literature. Further, if AMF were to be anti-angiogenic, yet provided vascular protection to the affected region, we would still advocate the use of AMF in the setting of irradiation, as its vasculo-protective effects provide a net-gain in terms of wound protection and healing in the irradiated field.

In addition to protecting non-fractured bone from the pernicious effects of radiation on the resident vasculature, AMF demonstrates assistance in a variety of irradiated bone healing and homeostasis models, such as distraction osteogenesis, and pathologic fracture healing. In these models, AMF has shown significant protection of parameters in union quality and integrity, mineralization capacity, bone mineral density, biomechanical response parameters, and histological metrics (12–19). Across this broad range of wound healing, AMF demonstrates efficacy in the protection and prevention of radiation induced complications associated with the treatment of head and neck cancer.

This study has several limitations. First, the casting technique used herein can determine vessel thickness, not vessel wall thickness. That information may be useful when gauging the effect of radiation on the ability of vessels to perfuse their surrounds with oxygen and nutrients. Second, the groups in this study had relatively small numbers, and as such the study may potentially be underpowered to detect some differences in metrics which were not found to be significant in this study, such as VN or VS. Lastly, due to the nature of the vascular casting technique, animals must be sacrificed in order to collect data, and as such we were only able to capture one timepoint at 56 days. This timepoint was selected because it represents a late-acute radiation response from previous studies of radiation damage on bone homeostasis and healing (29). It is known that radiation can have different effects at different timepoints, and as such, it would be useful to examine early-acute and chronic models as well. Thus, it is yet unknown if the promising protection provided by AMF here will translate to chronic protection from radiation damage. Lastly, we showed that radiation impairs both VVF and VT, but AMF only protects VT, yet provides substantial protection in radiomorphometric, histological, and biomechanical response parameters. The independent etiology of the contributions of VVF and VT to bony response to radiation has yet to be ascertained.

In conclusion, this model provides convincing evidence that the main pathologic effects of radiation injury on the vasculature of the mandible are mainly manifested through a mechanism of diminished luminal diameter. Furthermore, AMF has the capacity to protect the vascular network by preserving blood vessel caliber to levels of normal non-irradiated bone when administered prior to radiation therapy. Further research is necessary to identify the precise cellular mechanisms that account for the protection of vessel thickness that we have seen here. These results present an exciting outlet for future investigations including combination therapy with angiogenic phamacotherapeutics or cell lines to further delineate optimal methods to protect and subsequently restore vascular quality in the setting of irradiation. AMF prophylaxis thereby has unequivocally demonstrated translational potential to prevent the pathologic effects of vascular injury resulting from radiation therapy in patients suffering from head and neck cancer.

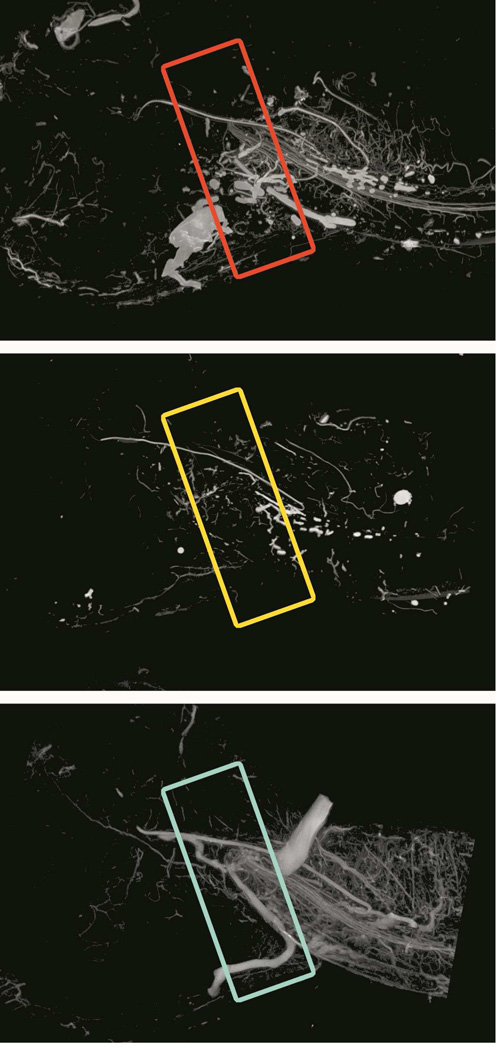

Figure 3.

Three-dimensional Maximal Intensity Pojection (MIP) µCT images of a Control (C) left-hemimandible (left image), a Radiated (XRT) left-hemimandible (middle image), and a Radiated left-hemimandible with Amifostine treatment (AMF XRT).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mary Davis and David Karnack for assistance with the delivery of radiotherapy. Supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (CA12587-01 and CA12587-06) to S.R.B and (T32-GM008616) to C.L.M. for A.D.

Funding Support provided by:

NIH T32-GM008616 to C.L. Marcelo, for A. Donneys

NIH R01 CA 12587-01 to S. R. Buchman

NIH R01 CA 12587-06 to S. R. Buchman

Abbreviations

- CT

computed tomography

- DA

degree of anisotropy; the directionality of the growth of vascularization in the ROI

- Gy

gray

- HNC

head and neck cancer

- LR

Lactated Ringer’s solution

- Micro-CT

micro-computed tomography imaging

- MIP

micro-CT maximal intensity projection

- ORN

osteoradionecrosis

- POD

post-operative day

- ROI

region of interest; defined in this experiment as a distance measuring 5.1 mm after the third molar of the left hemi-mandible

- SQ

subcutaneous injection

- VN

vessel number; number of vessels per millimeter within the ROI

- VS

vessel separation; the space in between adjacent vessels in the ROI

- VT

vessel thickness; the intraluminal diameter of the vessel of interest, does not include the thickness of the vessel wall

- VVF

vessel volume fraction; fraction of bone occupied by the volume of vessels within the ROI

- XRT

radiation therapy

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors do not have a conflict of interest to declare.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures 2013. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grandis JR, Pietenpol JA, Greenberger JS, Pelroy RA, Mohla S. Head and neck cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8126. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dimery W, Hong WK. Overview of combined modality therapies for head and neck cancer. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:95–111. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.2.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cutright DE, Brady JM. Long-term effects of radiation on the vascularity of rat bone: quantitative measurements with a new technique. Radiat Res. 1971;48:402–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pitaknen MA, Hopewell JW. Functional changes in the vascularity of the irradiated rat femur. Implications for late effects. Acta Radiol Oncol. 1983;22:253–256. doi: 10.3109/02841868309134038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deshpande SS, Donneys A, Farberg AS, Tchanque-Fossuo CN, Zehtabzadeh AJ, Buchman SR. Quantification and characterization of radiation-induced changes to mandibular vascularity using micro-computed tomography. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125:40. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e318255a57d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marx RE. Osteoradionecrosis: a new concept of its pathophysiology. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1983;41:283–288. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(83)90294-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marx RE, Johnson RP. Studies in the radiobiology of osteoradionecrosis and their clinical significance. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1987;64:379–390. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(87)90136-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brizel DM, Wasserman TH, et al. Phase III randomized trial of Amifostine as a radioprotector in head and neck cancer. JPN J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:3339. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.19.3339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andreassen CJ, Grau C, Lindegaard JC. Chemical radioprotection: A critical review of amifostine as a cytoprotector in radiotherapy. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2003;13:62. doi: 10.1053/srao.2003.50006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wasserman TH, Brizel DM, et al. Influence of intravenous Amifostine on xerostomia, tumor control, and survival after radiotherapy for head-and-neck cancer: 2-year follow-up of a prospective, randomized, phase III trial. Int J Radiat Oncol. 2005;63:985. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.07.966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tchanque-Fossuo CN, Donneys A, Razdolsky ER, Monson LA, Farberg AS, Deshpande SS, Buchman SR. Quantitative histologic evidence of Amifostine-induced cytoprotection in an irradiated murine model of mandibular distraction osteogenesis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130:1199–1207. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31826d2201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tchanque-Fossuo CN, Donneys A, Deshpande SS, Nelson NS, Boguslawski MJ, Gallagher KK, Buchman SR. Amifostine remediates the degenerative effects of radiation on the mineralization capacity of the murine mandible. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129:646e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182454352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tchanque-Fossuo CN, Donneys A, Sarhaddi D, Poushanchi B, Deshpande SS, Weiss DM, Buchman SR. The effect of Amifostine prophylaxis on bone densitometry, biomechanical strength and union in mandibular pathologic fracture repair. Bone. 2013;57:56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tchanque-Fossuo CN, Gong B, Poushanchi B, Donneys A, Sarhaddi D, Gallagher KK, Deshpande SS, Goldstein S, Morris M, Buchman SR. Raman spectroscopy demonstrates Amifostine induced preservation of bone mineralization patterns in the irradiated murine mandible. Bone. 2013;52:712–717. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2012.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tchanque-Fossuo CN, Poushanchi B, Sarhaddi D, Donneys A, Desphande SS, Weiss DA, Buchman SR. Amifostine therapeutic enhancement of vascularity in an irradiated model of mandibular fracture repair model. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130:21. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182a80766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spiegel JP, Donneys A, Sarhaddi D, Tchanque-Fossuo CN, Ahsan S, Deshpande SS, Buchman SR. Amifostine offers protection of osteocyte viability during fracture healing after radiotherapy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;131:69. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Monson LA, Farberg AS, Jing XL, Tchanque-Fossuo CN, Donneys A, Buchman SR. Distraction osteogenesis in the rat mandible following radiation and treatment with amifostine. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125:41. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Razdolsky ER, Tchanque-Fossuo CN, Donneys A, Farberg AS, Deshpande SS, Gallagher KK, Sarhaddi D, Poushanchi B, Buchman SR. Amifostine demonstrates significant cytoprotection in an irradiated murine model of mandibular distraction osteogenesis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127:69. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31826d2201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tchanque-Fossuo CN, Monson LA, Farberg AS, Donneys A, Deshpande SS, Razdolsky ER, Halonen NR, Goldstein SA, Buchman SR. Dose-response effect of human equivalent radiation in the murine mandible. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128:480e–487e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31822b67ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Monson LA, Farberg AS, Jing XL, Buchman SR. Human equivalent radiation dose response in the rat mandible. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:2. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Damron TA, Spadaro JA, Margulies B, et al. Dose response of Amifostine in protection of growth plate function from irradiation effects. Int J Cancer. 2000;90:73–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Damron TA, Margulies B, Biskup D, et al. Amifostine before fractionated irradiation protects bone growth in rats better than fractionation alone. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;50:479–483. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)01532-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eisbruch A. Amifostine in the treatment of head and neck cancer: intravenous administration, subcutaneous administration, or none of the above. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:119–121. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.5051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giannopoulou E, Katsoris P, Kardamakis D, Papadimitriou E. Amifostine inhibits angiogenesis in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;304:729–737. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.042838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giannopoulou E, Papadimitriou E. Amifostine has antiangiogenic properties in vitro by changing the redox status of human endothelial cells. Free Radic Res. 2003;37:1191–1199. doi: 10.1080/10715760310001612559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grdina DJ, Kataoka Y, Murley JS, Hunter N, Weichselbaum RR, Milas L. Inhibition of spontaneous metastases formation by amifostine. Int J Cancer. 2002;97:135–141. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grdina DJ, Kataoka Y, Murley JS, Swedberg K, Lee JY, Hunter N, Weichselbaum RR, Milas L. Antimetastatic effectiveness of amifostine therapy following surgical removal of Sa-NH tumors in mice. Semin Oncol. 2002;29:22–28. doi: 10.1053/sonc.2002.37357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buchman SR, Ignelzi MA, Radu C, Wilensky J, Rosenthal AH, Tong L, Rhee ST, Goldstein SA. Unique Rodent Model of Distraction Osteogenesis of the Mandible. Ann Plast Surg. 49:511–519. doi: 10.1097/00000637-200211000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]