Abstract

In US secondary schools, vending machines and school stores are a common source of low-nutrient, energy-dense snacks and beverages, including sugar-sweetened beverages, high fat salty snacks and candy. However, little is known about the prevalence of these food practices in alternative schools, educational settings for students at risk of academic failure due to truancy, school expulsion and behavioral problems. Nationwide, over 5000 alternative schools enroll about one-half million students, who are disproportionately minority and low-income youth. Principal survey data from a cross-sectional sample of alternative (n=104) and regular (n=339) schools collected biennially from 2002–2008 as part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Minnesota School Health Profiles were used to assess and compare food practice prevalence over time. Generalized estimating equation models were used to estimate prevalence, adjusting for school demographics. Over time, food practice prevalence decreased significantly for both alternative and regular schools, although declines were mostly modest. However, the decrease in high fat, salty snacks was significantly less for alternative than regular schools (−22.9% versus −42.2%; p<0.0001). Efforts to improve access to healthy food choice at school should reach all schools, including alternative schools. Study findings suggest high fat salty snacks are more common in vending machines and school stores in alternative schools than regular schools, which may contribute to increased snacking behavior among students and extra consumption of salt, fat and sugar. Study findings support the need to include alternative schools in future efforts that aim to reform the school food environment.

Keywords: school food environment, alternative schools, low-nutrient, energy dense foods

In US secondary schools, vending machines and school stores are a common source of low-nutrient, energy dense snacks and beverages that include sugar-sweetened beverages, high fat salty snacks and candy.1, 2 For over a decade, considerable multi-sector effort has been expended to improve the school food environment,3–7 with many reporting generally positive results.8–10 However, surveillance of the US school food environment has not typically included alternative schools, educational settings for students at risk of academic failure due to truancy, school expulsion and behavioral problems.11, 12 Nationwide, over 5000 alternative schools enroll about one-half million students in secondary alternative school programs, with enrollments increasing.13 Most students attend an alternative school between 7 and 12 months, and almost one-third attend for greater than one year.14 Students attending schools are disproportionately minority and low-income youth.11, 14

All youth will benefit from an improved school food environment, where access to low-nutrient, energy-dense snacks and beverages is limited. It is especially important to provide supportive school food environments for minority and low-income youth, many with an increased risk of overweight and obesity and weight-related morbidities, such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes.16, 17 Limited research suggests vending machines and school stores and the low-nutrient energy dense snacks and beverages sold in vending machines and school stores are common in the alternative school setting and availability may be linked to an increased consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and high fat foods.18–20

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) School Health Profiles is a biennial survey that assesses school health policies and practices in participating states and territories. CDC uses a random, systematic, equal-probability sampling strategy to produce representative samples of public secondary schools that include one or more of grades 6 through 12.21 In Minnesota, public schools that identified as alternative schools were included in the sampling frame from 2002 to 2008, providing a unique opportunity to compare and contrast the alternative and regular school food environments over time.22 In the current study, regular schools were defined as schools that did not identify as alternative, special education, distance learning or correctional/treatment facilities.22

Therefore, the purpose of the current study was 1) to examine the prevalence of select school food practices that included availability of vending machines and school stores and sugar-sweetened beverages, high fat salty snacks and candy sold in vending machines and school stores in alternative and regular schools and 2) to compare food practice prevalence within and between school type (alternative versus regular) over time. It was hypothesized that school type (alternative versus regular) would moderate the prevalence of food practices. The current study was conducted as part of the School Obesity-related Policy Evaluation (ScOPE) study, which aims to examine school obesity prevention policies in Minnesota secondary schools using existing state and national surveillance data.

METHODS

School-level data from the Minnesota School Health Profiles principal survey were used. Data collection for the present study occurred biennially between 2002 and 2008 and included a cross-sectional sample of alternative (n=104) and regular (n=339) secondary schools. School principals or a designee completed the mailed survey. Statewide participation rates for all years except 2006 were at least 70%.23 In 2006 the statewide response rate was 66% (P. Rhode, Minnesota Department of Health, personal communication, 2012). Since weighted data were not available from CDC for 2006,23 data for the current study were analyzed without weights. However, all models included an adjustment for the original stratification scheme. Furthermore, sensitivity analysis of item responses across survey years found minimal differences when comparing weighted to unweighted data.

For the present study, the following questions from the Minnesota Profiles principal survey were examined: 1) Can students purchase snack foods or beverages from one or more vending machines at school or at a school store, canteen or snack bar; and if yes, 2) Can students purchase each of the following snack foods or beverages from vending machines or at the school store, canteen or snack bar: a) soda pop or fruit drinks that are not 100% juice and/or sports drinks (coded as sugar sweetened beverages); b) chocolate candy and/or other kinds of candy (coded as candy); and c) salty snacks that are not low in fat (coded as high fat salty snacks).24, 25 Responses for all items were Yes/No.

School-level demographic characteristics obtained from the National Center for Educational Statistics (NCES) Common Core Data included: percent free/reduced price lunch eligibility categorized as < 40% or ≥ 40%, and percent minority enrollment categorized as < 20% or ≥ 20%.26 School grade level information was obtained from the Minnesota Department of Education.22 All schools in the sample included the 12th grade, with the exception of two schools where the highest grade level was 11. The low grade varied across schools from 4 to 9. For analysis, school grade level was dichotomized as high grade 11 or 12 and low grade 9 versus high grade 11 or 12 and low grade 4–8. A combination of NCES and Rural-Urban Commuting Areas classification schemes were used to classify school location as city, suburban or town/rural.26, 27 The study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Minnesota.

Logistic regression models were used to estimate prevalence of vending machines and school stores and sugar-sweetened beverages, high fat salty snacks and candy in vending machines and school stores in alternative and regular schools. Separate logistic regression models were estimated for each of the four outcomes. Statistical significance was accepted at a p-value of < 0.05. No adjustments were made to the reported p-values to reflect the multiple hypotheses that were tested. All models included the main predictor, school type (alternative or regular), year and school level demographics (percent free/reduce price lunch eligibility, percent minority enrollment, school grade level, school location). To account for the small number of schools that were included in multiple surveys, generalized estimating equation logistic models with an independent correlation structure were used. Models that included an interaction term between school type and year did not identify a significant effect at p < 0.05 level on the logistic scale. Therefore, interaction terms were not included in the final models. The adjusted prevalence of each food practice was estimated from the logistic model. Change in practice prevalence over time was computed by comparing the difference between 2002 and 2008 adjusted prevalence. Difference in practice prevalence between the school types was estimated by calculating the difference in practice prevalence between school types, averaged over all years. The figure compares crude prevalence for each food practice by school type. Analyses were conducted with StataCorp. 2011. Stata Statistical Software: Release 12. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP.

RESULTS and DISCUSSION

Table 1 compares demographics by school type. The alternative school sample was significantly more racially diverse than the regular school sample and included a larger proportion of schools where 40% or more of students were eligible for the free/reduced price lunch program. A majority of schools were located in towns/rural areas. However, regular schools were significantly more likely to be in towns and rural areas than alternative schools (77% versus 55%; p < 0.0001). National data indicate that alternative schools are more typically located in urban and suburban areas14

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of alternative and regular public secondary schools, Minnesota, 2002–2008

| Alternative N = 104 N (%) |

Regular N = 339 N (%) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| School grade levela | |||

| High grade 11 or 12 and low grade 9 | 57 (55%) | 162 (48%) | 0.2103 |

| High grade 11 or 12 and low grade 4–8 | 47 (45%) | 177 (52%) | |

| School locationb | |||

| City | 24 (23%) | 36 (11%) | <0.0001 |

| Suburban | 23 (22%) | 41 (12%) | |

| Town/rural | 57 (55%) | 262 (77%) | |

| Free/Reduced Price Lunch Eligibilityc | |||

| < 40% | 55 (53%) | 265 (78%) | <0.0001 |

| ≥ 40% | 49 (47%) | 74 (22%) | |

| Minority Enrollmentc | |||

| < 20% | 50 (48%) | 279 (82%) | <0.0001 |

| ≥ 20% | 54 (52%) | 60 (18%) |

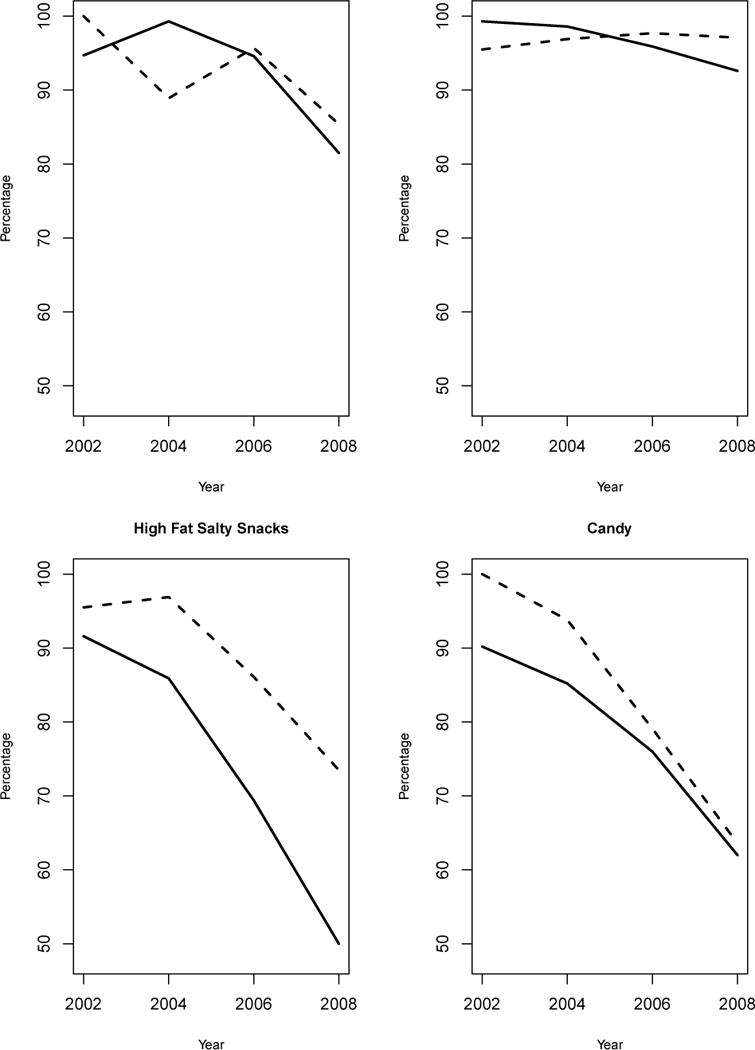

Figure 1 compares the crude percentage for each food practice by year for alternative and regular schools. Table 2 shows the trends in food practice prevalence both within and between school types, adjusted for school-level demographics. Prevalence of all food practices was similar in alternative and regular schools in 2002 and consistent with other studies at that time indicating vending machines and school stores that sold sugar-sweetened beverages, high fat salty snacks and candy were readily available in most US secondary schools.28 By 2008, in both alternative and regular schools, a significant decrease in prevalence occurred for all food practices except sugar-sweetened beverages, which showed a significant decrease in regular schools but not alternative schools. However, prevalence remained high in 2008. This was especially true for sugar-sweetened beverages, which were available in vending machines and school stores in more than 90% of all schools. Other studies examining the availability of sugar-sweetened beverages in large representative samples of US secondary schools have shown similar results, confirming that over time decreases in the prevalence of sugar-sweetened beverages have been modest.2, 10

Figure 1.

Crude percentage of alternative (dashed line) and regular schools (solid line) with vending machines and school stores and sugar–sweetened beverages, high fat salty snacks and candy sold in vending machines and school stores, Minnesota, 2002–2008.

Table 2.

Prevalencea of select food practices, alternative and regular public secondary schools, Minnesota, 2002–2008

| Food Practice | School Type | Prevalencea 2002 |

Prevalencea 2008 |

Change in prevalencea (confidence interval) within school type 2002–2008 |

p-value for change over time | p-value for difference between school typeb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vending machines/school stores | Alternative (n=137c) | 98.1% | 89.8% | −8.3% (−4.6%, −1.9%) | 0.0107 | 0.2429 |

| Regular (n=561c) | 97.0% | 85.5% | −11.5% (−17.8%, −5.3%) | 0.0003 | ||

| Sugar-sweetened beverages | Alternative (n=125c) | 99.3% | 96.0% | −3.3% (−7.2%, 0.7%) | 0.1025 | 0.3702 |

| Regular (n=514c) | 98.7% | 92.9% | −5.8% (−11.0%, −0.6%) | 0.0292 | ||

| High fat, salty snacks | Alternative (n=123c) | 97.3% | 74.4% | −22.9% (−33.1%, −12.7%) | < 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

| Regular (n=512c) | 92.4% | 50.2% | −42.2% (−51.5%, −32.9%) | < 0.0001 | ||

| Candy | Alternative (n=122c) | 94.1% | 70.9% | −23.2% (−33.3%, −13.2%) | < 0.0001 | 0.1272 |

| Regular (n=513c) | 91.3% | 61.7% | −29.6% (−38.6%, −20.6%) | < 0.0001 |

From logistic regression models adjusted for school grade level (dichotomized as high grade 11 or 12 and low grade 9 versus high grade 11 or 12 and low grade 4–8), location (defined using a combination of National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) Common core data and Rural Urban Commuting Area classification schemes)26, 27 and percent free/reduced price lunch eligibility and percent minority enrollment defined using NCES Common core data criteria.26

Differences between school type (alternative and regular) are averaged over all years.

n = total number of observations over time not the total number of unique schools; n varies for models due to missing data for some items

For most food practices, the change in adjusted prevalence from 2002 to 2008 between alternative and regular schools was not statistically significant. However, the decrease over time in high fat, salty snacks was significantly less for alternative schools than regular schools (−22.9% versus −42.2%; p<0.0001). Prior studies have demonstrated a significant association between the availability of snack vending in secondary schools and increased snack food purchases by students, as well as lower fruit intake.29, 30 Recent analysis of a nationally representative sample of US youth found an increase in snacking behavior between 1977–1998 and 2003–2006, with the largest increase in snacking calories coming from salty snacks and also candy.31 High fat, salty snacks, such as regular potato chips, corn chips and crackers are a common source of dietary sodium.32 It is well recognized that most Americans consume too much sodium,32 which can contribute to the development of hypertension and an increased risk of heart disease and stroke.33 A 2013 Institute of Medicine report addressing dietary sodium identified the reduction of excess sodium intake as a public health priority and linked success of reduction efforts to decreasing sodium in the environment.33, 34 High-fat, salty snacks are also a common source of saturated fat and added sugar.32 Higher intakes of saturated fat are linked to higher levels of total and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, recognized risk factors for cardiovascular disease.32 Added sugar contributes to excess calorie intake which is associated with weight gain.32 However, research linking snacking and weight status is inconclusive at this time.35

Altogether, findings from the current study suggest that high fat salty snacks are more common in vending machines and school stores in alternative schools than regular schools. Increased availability may contribute to increases in snacking behavior among students and extra consumption of dietary sodium, saturated fat and sugar.18–20 Student access to high fat salty snacks during the school day has received little attention, despite increases in youth snacking and growing concerns related to excess sodium consumption and increasing rates of hypertension and cardiovascular disease.31, 33

This study has strengths and limitations. Few studies have examined the alternative school food environment. The current study adds to the literature by providing a comparative assessment of trends over time in the prevalence of select food practices in the alternative and regular school food environment. However, since 2008, Minnesota School Health Profiles has not included alternative schools in their sampling frame. Therefore, extending the trend study beyond 2008 is not possible. Interestingly, recent studies evaluating the secondary school food environment since 2008 have found an increase in availability of competitive food venues and the low-nutrient energy-dense snacks and beverages typically sold in these venues,10, 36, 37 suggesting the modest declines in food practice prevalence seen across school type in the current study may not be sustainable and ongoing monitoring is indicated. Other strengths of the current study include the linking of multiple existing data sets that included the CDC Minnesota School Health Profiles, NCES Common Core Data and Rural-Urban Commuting Areas classifications. This permitted a description and comparison of important school-level demographic characteristics by school type, location, minority enrollment and free/reduced price lunch eligibility, as well as adjustment for these characteristics in multivariate analysis. The use of self-reported data from a sample of principals or their designees was a study limitation. Further, study results may not be generalizable to schools outside Minnesota.

CONCLUSIONS

Efforts to improve access to healthy food choice at school should reach all schools, including alternative schools. In 2008, the availability of high fat salty snacks in vending machines and school stores was significantly higher in alternative than regular schools, which may contribute to increased snacking behavior among students and extra consumption of salt, fat and sugar. Study findings support the need to include alternative schools in future efforts that aim to reform the secondary school food environment.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development, grant #R01-HD070738.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure

All of the authors for this paper have indicated that there is no conflict of interest to disclose.

Contributor Information

Martha Y. Kubik, Email: kubik002@umn.edu, University of Minnesota, School of Nursing, 5-140 Weaver Densford Hall, 308 Harvard St SE, Minneapolis, MN 55455, Telephone: 612.625.0606; Fax: 612/625.7091.

Cynthia Davey, University of Minnesota, Biostatistical Design and Analysis Center, Clinical and Translational Science Institute, Minneapolis, MN.

Richard F. MacLehose, University of Minnesota, Division of Epidemiology & Community Health, Minneapolis, MN.

Brandon Coombes, University of Minnesota, Division of Biostatistics, Minneapolis, MN.

Marilyn S. Nanney, University of Minnesota, Family Medicine and Community Health, Minneapolis, MN.

References

- 1.O’Toole TP, Anderson S, Miller C, et al. Nutrition services and foods and beverages available at school: Results from the School Health Policies and Programs Study 2006. J Sch Health. 2007;77:500–521. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.School Nutrition Dietary Assessment Study-IV, Summary of Findings. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Food and Nutrition Services. Office of Research and Analysis; Nov, 2012. http://www.mathematica-mpr.com/publications/PDFs/nutrition/snda-iv_findings.pdf. Accessed July 31, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alliance for a Healthier Generation. Healthy Schools Program. https://www.healthiergeneration.org/_asset/l062yk/07-278_HSPFramework.pdf/. Published 2013. Accessed February 3, 2014.

- 4.Boehmer TK, Brownson RC, Haire-Joshu D, Dreisinger ML. Patterns of childhood obesity prevention legislation in the United States. Prev Chronic Dis [serial online] 2007 Jul; http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2007/jul/06_0082.htm. Accessed February 3, 2014. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Institute of Medicine Nutrition standards for foods in schools: Leading the way toward healthier youth Report brief. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.S. 2507 (108th): Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act of 2004. https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/108/s2507. Accessed February 3, 2014.

- 7.Let’s Move. Healthy Schools. http://www.letsmove.gov/eat-healthy. Accessed February 3, 2014.

- 8.Center for disease Control and Prevention Competitive Foods and Beverages in US Schools: A State Policy Analysis. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2012. http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/nutrition/pdf/compfoodsbooklet.pdf. Accessed July 31, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chriqui JF, Resnick EA, Schneider L, Schermbeck R, Adcock T, Carrion V, Chaloupka FJ. School Years 2006–07 through 2010–11. Vol. 3. Chicago, IL: Bridging the Gap Program, Health Policy Center, Institute for Health Research and Policy, University of Illinois at Chicago; 2013. School District Wellness Policies: Evaluating Progress and Potential for Improving Children’s Health Five Years after the Federal Mandate. http://www.bridgingthegapresearch.org/_asset/13s2jm/WP_2013_report.pdf. Accessed July 31, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Terry-McElrath YM, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM. Trends in competitive venue beverage availability:Findings from US Secondary Schools. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166:776–778. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2012.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kleiner B, Porch R, Farris E. Public alternative schools and programs for students at risk Of education failure: 2000–01 (NCES 2002–004). US Department of Education. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kyle TM, Brener ND, Kann L, Ross JG, Roberts AM, Iachan R, Robb WH, McManus T. Methods: School Health Policies and Program Study 2006. J Sch Health. 2007;77:398–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Center for Education Statistics. Digest of Education Statistics. Number and enrollment of public elementary and secondary schools, by school type, level, and charter and magnet status: Selected years, 1990–91 through 2009–10. http://www.nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d11/tables/dt11_101.asp. Accessed July 15, 2013.

- 14.Lehr CA, Moreau RA, Lange CM, Lanners EJ. Alternative schools: Findings from a national survey of the states. Institute on Community Integration. The College of Education & Human Development, University of Minnesota; Sep, 2004. http://www.eric.ed.gov/PDFS/ED502534.pdf. Accessed July 18, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC health disparities and inequality report – United States, 2011. MMWR. 2011;60(Suppl):1–113. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/other/su6001.pdf. Accessed July 18, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Flegal KM. High body mass index for age among US children and adolescents, 2003–2006. JAMA. 2008;299:2401–2405. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.20.2401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Ferranti SD, Gauvreau K, Ludwig DS, Neufield EJ, Newburger JW, Rifai N. Prevalence of the Metabolic Syndrome in American Adolescents. Findings from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Circulation. 2004;110:2494–2497. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000145117.40114.C7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kubik MY, Lytle LA, Fulkerson JA. Fruits, vegetables and football: Results from focus groups with alternative high school students regarding eating and physical activity. J Adolesc Health. 2005;36:494–500. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kubik MY, Lytle LA, Fulkerson JA. Physical activity, dietary practices and other health behaviors of at-risk youth attending alternative high schools. J Sch Health. 2004;74:119–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2004.tb06613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arcan C, Kubik MY, Fulkerson JA, Davey C, Story M. Association between food opportunities during the school day and selected dietary behaviors of students attending alternative high schools. Prev Chronic Dis. 2011;8(1) http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2011/jan/09_0214.htm. Accessed July 31, 2013. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Adolescent and School Health. School Health Profiles. http:://www.cdc.gov/HealthyYouth/profiles/index.htm. Accessed March 1, 2013.

- 22.Minnesota Department of Education. http://w20.education.state.mn.us/MDEAnalytics/Data.jsp. Accessed March 20, 2013.

- 23.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Adolescent and School Health. School Health Profiles. Participation history and data quality 1996–2010. http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/profiles/history.htm. Accessed July 31, 2013.

- 24.Whalen LG, Grunbaum JA, Kann L, Hawkins J, McManus T, Davis KS. School Health Profiles: Surveillance for Characteristics of Health Programs among Secondary Schools (Profiles 2002) Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brener ND, Demissie Z, Foti K, McManus T, Shanklin SL, Hawkins J, Kann L. School Health Profiles 2010: Characteristics of Health Programs Among Secondary Schools. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Center for Education statistics. Common core of Data. http://nces.ed.gov/ccd/. Accessed March 20, 2013.

- 27.U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. Rural-urban community area codes. http://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-commuting-area-codes.aspx. Accessed March 20, 2013.

- 28.Wechsler H, Brener ND, Kuester S, Miller C. Food Service and Foods and Beverages available at school: Results from the School Health Policies and Program Study 2000. J Sch Health. 2001;71(7):313–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2001.tb03509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neumark-Sztainer D, French SA, Hannan PJ, Story M, Fulkerson JA. School lunch and snacking patterns among high school students: associations with school food environment and policies. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2005 Oct 6;2(1):14. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-2-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kubik MY, Lytle LA, Hannan PJ, Perry CL, Story M. The association of the school food environment with dietary behaviors of young adolescents. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1168–1173. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.7.1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Piernas C, Popkin BM. Trends in snacking among US children. Health Aff. 2010;29:398–404. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010. 7. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2010. http://www.dietaryguidelines.gov. Accessed July 31, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sodium intake in populations Assessment of evidence Report Brief. Institute of Medicine of the National Academies; May, 2013. http://www.iom.edu/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2013/Sodium-Intake-Populations/SodiumIntakeinPopulations_RB.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Strom BL, Anderson CAM, Ix JH. Sodium reduction in populations. Insights from the Institute of Medicine Committee. JAMA. 2013;310(1):31–32. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.7687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Larson N, Story M. A review of snacking patterns among children and adolescents: What are the implications of snacking for weight status? Childhood Obesity. 2013;9:104–115. doi: 10.1089/chi.2012.0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kubik MY, Davey C, Nanney MS, MacLehose RF, Nelson TF, Coombes B. Vending and school store snack and beverage trends. Minnesota secondary schools, 2002 to 2010. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(6):583–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robert Wood Johnson and PEW Health Group. Kids’ safe healthful foods project. Out of balance. A look at snack foods in secondary schools across the states. 2012 Oct; http://www.pewhealth.org/uploadedFiles/KSHF_OutofBalance_WebFINAL102612.pdf. Accessed February 3, 2014.