Abstract

Background

Accurate, adequate, and timely food and nutrition information is necessary in order to monitor changes in the US food supply and assess their impact on individual dietary intake.

Objective

Develop an approach that links time-specific purchase and consumption data to provide updated, market representative nutrient information.

Data and Methods

We utilized household purchase data (Nielsen Homescan, 2007–2008), self-reported dietary intake data [What We Eat in America (WWEIA), 2007–2008], and two sources of nutritional composition data. This factory to fork Crosswalk approach connected each of the items reported to have been obtained from stores from the 2007–2008 cycle of the WWEIA dietary intake survey to corresponding food and beverage products that were purchased by US households during the equivalent time period. Using nutrition composition information and purchase data, an alternate Crosswalk-based nutrient profile for each WWEIA intake code was created weighted by purchase volume of all corresponding items. Mean intakes of daily calories, total sugars, sodium, and saturated fat were estimated.

Results

Differences were observed in the average daily calories, sodium and total sugars reported consumed from beverages, yogurts and cheeses, depending on whether the FNDDS 4.1 or the alternate nutrient profiles were used.

Conclusions

The Crosswalk approach augments national nutrition surveys with commercial food and beverage purchases and nutrient databases to capture changes in the US food supply from factory to fork. The Crosswalk provides a comprehensive and representative measurement of the types, amounts, prices, locations and nutrient composition of CPG foods and beverages consumed in the US. This system has potential to be a major step forward in understanding the CPG sector of the US food system and the impacts of the changing food environment on human health.

Keywords: Food composition, nutrient profile, United States, dietary intake, nutrition assessment

Introduction

The modern, global food supply is complex, ever changing and expanding. In 2010 we identified over 85,000 uniquely formulated food and beverage products in the consumer packaged goods (CPG) sector of the US food system alone.1 The introduction of new products, removal of out of favor products, and reformulations of existing products results in continuous change and turnover of the food supply. In contrast, the resources available to countries across the globe to monitor this dynamic food system and to understand its impacts on human health are limited.

Accurate, adequate, and timely food and nutrition information is necessary for planning and evaluating the effects of nutrition programs and policies, for predicting future dietary intake trends, and for understanding the impacts of the changing food environment on health. Nutrition researchers have based our understanding of US diets, in large part, on foods reported in national nutrition surveys such as What We Eat in America (WWEIA), the dietary intake component of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). However, the number of unique foods and beverages reported in any given two-year collection period of WWEIA is much smaller than the number of products available in the marketplace (approximately 7,300 reported items in 2009–2010 as compared to >85,000 products available). Furthermore, updates of the national food composition data which are used to determine nutrient intakes occur infrequently due to limited resources. Consequently, many government and advisory reports have noted the need to enhance the accuracy and adequacy of food system surveillance in the US.2–4

In this paper, we describe an approach for monitoring US food and nutrient information from the factory to the fork. We focus on the consumer packaged goods (CPG) food and beverage sector as it accounts for over 60% of caloric intake among US children and adolescents5 and is the most difficult component of the food supply to monitor due to the dynamic nature of product offerings. The Crosswalk we have developed augments national nutrition surveys with commercial food and beverage purchase and nutrient databases to capture changes in the US food supply from factory to fork. Our paper describes the factory to fork Crosswalk developed to link each of the foods and beverages reported in a given cycle of the WWEIA-NHANES to corresponding CPG food and beverage items that were purchased by US households during the equivalent time period.

METHODS

Nielsen Homescan (commercial CPG purchases data)

For this paper, Nielsen Homescan data from 2007 through 2008 were used. Homescan contains detailed bar code-level information about household food purchases brought into the home and contains all bar code transactions from all outlet channels, including grocery, drug, mass-merchandise, club, supercenter, and convenience stores. The data are collected daily by providing scanning equipment to a sample of 35,000–60,000 households across 76 major metropolitan and non-metropolitan markets in the panel survey each year.6 All purchases are linked to retail stores and markets and include price paid. Homescan also contains key sociodemographic and household composition data and basic geographical identifiers, as well as household weights for each year of data in order for analyses using Homescan to be nationally representative.7–9 Others scholars and government agencies have used and evaluated these data, and have found that, while the sample tends to be older and higher income, the household weights provided by Nielsen re-weights the sample to be nationally representative for CPG purchases.7,8,10

Nutrition Facts Panel (NFP) data (commercial CPG nutrition data)

Nutrition Facts Panel (NFP) data are the nutrition data found on food labels of CPG products. As required by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), label data contain information on serving-size measurement, total calories, calories from fat, total fat, saturated fat, trans fat, total sugars, total carbohydrate, protein, dietary fiber, sodium, cholesterol, vitamin A, vitamin C, calcium, and iron.11 Commercial NFP data sources also contain the full ingredient list, brand name, and all other printed material on each product package. We obtained the NFP data from a number of commercial sources (e.g., Mintel Global New Product Database and Datamonitor Product Launch Analytics), described in earlier publications.5 The NFP data includes date of data collection, and there can be multiple NFP records for some bar coedes over time. For the purposes of this paper linking foods purchased to foods consumed in 2007–2008, we used NFP records that were collected between 2006 and 2009 (using the closest date when more than one record was available) for matching with the Nielsen Homescan 2007 and 2008 purchase data. There is currently no existing way to validate the accuracy of the over 200,000 records of NFP data.

What We Eat in America, WWEIA (public dietary intake data)

WWEIA is the dietary intake interview component of the NHANES and is conducted as a partnership between the US Department of Health and Human Services and the US Department of Agriculture (USDA). It is the only nationally representative survey that includes detailed 24-hour dietary intake data of US individuals. Since the creation of this merged survey, WWEIA provides nationally representative data for two-year periods. Since the focus of the Crosswalk is on CPG products, the WWEIA analyses only include intake reported as obtained in stores and through vending. For this paper, data from 2007–08 were used.

Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies, FNDDS (public food composition data)

FNDDS, the source of nutrient data for WWEIA-NHANES is based on nutrient values in the USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference (SR).6,12 The comparison presented here uses FNDDS version 4.1, which is based on SR release 22 (corresponding to foods and beverages reported in WWEIA-NHANES 2007–08.13

Factory to Fork Crosswalk Methods

The major steps used in creating the Crosswalk include (see detailed explanation below):

Create a list of USDA food codes that represent foods and beverages reported consumed in a given WWEIA-NHANES cycle, and determine where each food was obtained (e.g., store, restaurant).

Map USDA food codes to corresponding commercial bar codes.

Convert nutrient information of bar codes from ‘as purchased’ to ‘as consumed’ form if needed.

Create a Crosswalk-based nutrient profile for each USDA food code.

Step 1: Create a list of foods reported consumed in a given WWEIA-NHANES cycle and determine food source

For WWEIA-NHANES 2007–08 data, we used all available dietary recalls to create a list of all foods and beverages reported consumed and reported as having been obtained from stores and vending. A number of items reported in WWEIA-NHANES 2007–08 could not be mapped to the purchased bar codes (e.g., loose fruits and vegetables, cuts of meat sold by weight, home prepared items). In each of these cases, the FNDDS nutrient profile was used. We have completed the Crosswalk for beverages, yogurts, and cheeses and present those results in this paper.

Step 2: Map USDA food codes to corresponding commercial bar codes

USDA food codes identified in step one were mapped to commercial bar codes purchased by households participating in the Nielsen Homescan panel in 2007 and 2008. Links between products were based on information available in commercial databases (item description and commercial categorization of product) and marketing of products. All matching was performed by a team of registered dietitians (RDs) who first reviewed the USDA food codes to group USDA food codes together based on various similarities in food form, intended use, production methods, and ingredients. The research team jointly determined appropriate large groups (e.g. cheese, yogurt) and reviewed the independently designated smaller groups (e.g., cottage cheese, mozzarella cheese, cream cheese).

Matching of individual bar codes to specific USDA food codes occurred at the smaller group level. In order to standardize matching, RDs first independently matched a sample of USDA food codes, and then the research team jointly determined decision rules that would be applied to the remaining matches. Each RD independently documented the rationale for matching. A detailed description of the linking process is provided in Appendix 1.

Step 3: Convert nutrient information from ‘as purchased’ to ‘as consumed’ form, if needed

As the WWEIA-NHANES is a dietary intake survey, the 8-digit USDA food codes that are the foundation of the Crosswalk are primarily in the ‘as consumed’ form. Subsequently, prior to the creation of a Crosswalk-based nutrient profile for each USDA food code, the as purchased nutrient data for some of the products from the commercial databases was adapted to reflect the nutrients of the products as consumed. In brief, all products linked to a USDA food code were sorted by market share, and unique product-specific preparation factors were created for products that accounted for the top 25% of dollars spent within that food code (or for the top ten products, if fewer than ten products accounted for 25% of dollars spent). Unique factors were based on the manufacturers’ directions for preparing the products for consumption, and each unique factor was also applied to identical products with a different bar code (e.g., a unique factor created for a single serving beverage concentrate with the highest market share would be applied to a larger package of the same beverage concentrate with a lower market share). Identical products were determined using product descriptions, attributes, nutrients, and ingredients. Once all unique factors were assigned, a weighted average of the unique factors was assigned to all remaining products.

When products needed to be adapted to match the USDA food code form, unique product-specific preparation factors were derived based on manufacturers’ directions and applied to the as purchased forms (Figure 1). Beverage products, as purchased, exist in three main forms: ready-to-drink, liquid concentrate, and powder concentrate. A detailed description of the preparation factors for each beverage form is provided in Appendix 2.

Figure 1.

Product-specific preparation factors used for converting beverage nutrient information from ‘as purchased’ to ‘as consumed’ form.

Step 4: Create a Crosswalk-based nutrient profile for each USDA food code

For each USDA food code, a Crosswalk-based nutrient profile was created by weighting the nutrient information by the purchase volume (or weight) of all bar codes linked with that USDA food code. For all products measured in mL, including ready-to-drink beverages, USDA food code-specific density factors were derived using the weight for a given volume of a beverage from the FNDDS. For each USDA food code Crosswalk-based nutrient profile, RDs performed a series of checks to confirm that nutrient values were appropriate and reasonable. Checks included examinations of bar code outliers within each code, examinations of all bar codes for USDA food codes where fewer than 5 bar codes were linked, and examination of all cases where the FNDDS nutrient profile and the UNCFRP nutrient profile differed by more than 50%.

Statistical Analysis

To compare the data from the Crosswalk approach with the standard USDA FNDDS data, we conducted two sets of analyses. First, we compared the Crosswalk nutrient profiles with the FNDDS 4.1 nutrient profiles for corresponding USDA food codes. Second, we compared Day 1 dietary intakes from WWEIA-NHANES using the Crosswalk nutrient data and the FNDDS 4.1 nutrient data. Dietary recalls (Day 1 only) for all respondents with data on dietary intake variables of interest were included in the analysis. Appropriate weighting factors were applied to adjust for differential probabilities of selection and various sources of nonresponse. The Crosswalk nutrient profiles and the FNDDS 4.1 were each applied to the dietary recall data (N=8528) from stores only for respondents two years of age and older. Mean intakes of calories, sodium, saturated fat, and total sugar from each beverage category and the yogurt and cheese categories were estimated separately for each nutrient profile. To test for statistical differences between nutrient profiles, we used independent 2-sample t tests. Differences were considered statistically significant at the p <0.05 level. Data analyses were conducted using SAS (version 9.3, 2010, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

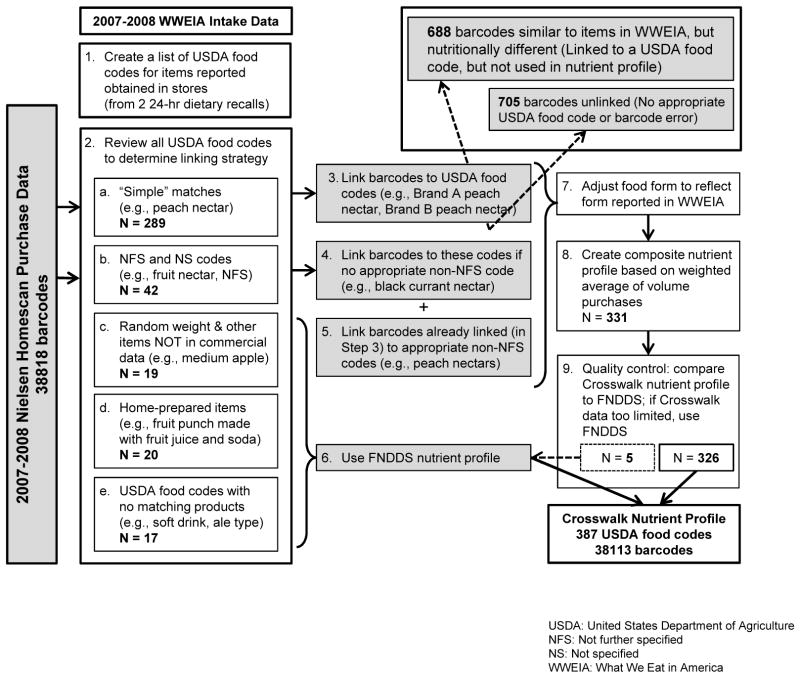

The 2007–08 factory to fork Crosswalk has been completed for all beverages, yogurts, and cheeses. Figure 2 summarizes the linking process and outcome of all USDA and bar codes. A total of 387 unique beverages, yogurts, and cheeses were reported as obtained in stores in WWEIA-NHANES 2007–2008. In comparison, a total of 38,113 unique beverages, yogurts, and cheeses were purchased by households in the Nielsen Homescan panel data in 2007–2008.

Figure 2.

Summary of the linking process and outcome of all USDA and BAR CODE codes utilized in the Crosswalk of beverages, cheese and yogurt items.

All USDA codes representing random weight items (n=19, e.g., lemon juice, freshly squeezed), home prepared items (n=20, e.g., fruit punch made with fruit juice and soda), and other items not found in the commercial database (n=17, e.g., cantaloupe nectar) were not mapped to commercial bar codes. These items represent less than 14% of total caloric consumption of beverages (53 USDA codes) and 2% of total caloric cheese consumption (4 USDA codes). There were no unlinked yogurt USDA codes. For all 56 USDA codes that were not linked to bar codes, the nutrient profile from the FNDDS version 4.1 was used.

Various bar codes purchased by households in the Nielsen Homescan panel data in 2007–08 were not included in the Crosswalk-based nutrient profile. There were 688 food and beverage products which were similar to items reported in WWEIA, though nutritionally different (e.g., nonfat cottage cheese, liquid ready-to-drink chocolate milk sweetened with non-nutritive sweeteners, strawberry juice) (Figure 2). Therefore these products were linked to a USDA food code, but not used in the Crosswalk-based nutrient profile. An additional 705 food and beverage products purchased by households in 2007–2008 were not similar to any items reported in the WWEIA-NHANES 2007–2008 or contained an uncorrectable error in the bar code information and, therefore, were not linked to a USDA food code. Finally, five USDA codes were linked to bar codes for which a small serving size and/or weight of the product combined with FDA rounding rules in NFP information led to inaccuracies of the Crosswalk-based nutrient profile. In these five cases, the nutrient profile from the FNDDS version 4.1 was used. These items represent less than 1% of total purchases of beverages, yogurts, and cheeses purchased by Homescan households in 2007–2008.

Food code nutrient profiles: comparison of Crosswalk nutrient profiles and the FNDDS

Nutrient profiles for 326 USDA food codes have been created based on the weighted average of volume purchases for successfully linked bar codes in Homescan 2007–2008. Between 1 and 7,505 bar codes were linked to each USDA food code. Caloric differences between nutrient profiles ranged from minimal (no calorie difference) to substantial (more than 158 calorie/100g difference). Figure 3 provides a comparison of nutrient profiles for two beverages. For low-fat fluid cow’s milk, differences between all nutrients were negligible while noteworthy differences in calories, sodium, carbohydrates, and sugars were observed for low-fat chocolate milk.

Figure 3.

Comparison of alternate nutrient profiles for 1% milk and chocolate lowfat milk.

Comparison of nutrient intake results

Differences were observed in the average daily calories, sodium, and total sugars reported consumed from beverages, yogurts, and cheeses depending on whether the FNDDS 4.1 or the Crosswalk nutrient profiles were used. Average caloric intake of fluid milk and sugar sweetened beverages was higher when the Crosswalk nutrient profiles were applied to WWEIA-NHANES 2007–08 intake data as compared to when the FNDDS 4.1 was applied to the same intake data (Table 1). In contrast, lower caloric intakes were observed for energy drinks, fruit juice, sports drinks, yogurts and cheese/cheese products when using the Crosswalk nutrient profiles as compared to the FNDDS 4.1. Average sodium intake from total beverages, coffee/tea, fluid milk, fruit juice, sugar sweetened beverages and cheese was higher when the Crosswalk nutrient profiles were applied to WWEIA-NHANES 2007–08 intake data as compared to when the FNDDS 4.1 was applied to the same intake data (Table 2). In contrast, lower sodium intakes were observed from water products when using the Crosswalk nutrient profiles as compared to the FNDDS 4.1. Average total sugars intake from total beverages, coffee/tea, sports drinks, fruit juice, and sugar sweetened beverages was higher when the Crosswalk nutrient profiles were applied to WWEIA-NHANES 2007–08 intake data as compared to when the FNDDS 4.1 was applied to the same intake data (Table 2). There were no significant differences in saturated fat intakes when alternate nutrient profiles were applied (Table 2).

Table 1.

Average daily calories reported consumed from select food groups by applying FNDDS vs. Factory to Fork Crosswalk nutrient profile to WWEIA-NHANES 2007–2008 consumption from stores only (ages 2 years and older, N=8528).

| Calories (kcal/capita/day) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food/Beverage Group | Number of USDA codes | Number of Unique Bar Codes | Number of Linked Bar Codes | Applying FNDDS 4.1 | Applying Crosswalk nutrient profile | Difference p value |

| Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | |||||

| Coffee/tea | 65 | 2796 | 8989 | 17.01 (1.52) | 18.85 (1.81) | 0.0413 |

| Energy drinks | 10 | 526 | 641 | 2.57 (0.41) | 2.34 (0.33) | 0.0038 |

| Fluid milk | 58 | 4328 | 8839 | 74.71 (2.96) | 76.64 (3.08) | <.0001 |

| Fruit juice | 46 | 4028 | 9373 | 32.79 (1.72) | 31.65 (1.65) | <.0001 |

| Meal replacement beverages | 3 | 35 | 59 | 0.29 (0.16) | .28 (0.16) | 0.1272 |

| Soy/Yogurt/Milk-based beverages | 17 | 912 | 1189 | 4.39 (0.53) | 4.18 (0.46) | 0.1964 |

| Sports drinks | 4 | 512 | 519 | 6.92 (0.9) | 5.52 (0.71) | <.0001 |

| Sugar sweetened beverage | 50 | 9525 | 14567 | 85.75 (7.01) | 89.44 (7.44) | <.0001 |

| Vegetable juice | 10 | 533 | 583 | 0.96 (0.13) | 0.9 (0.12) | 0.2851 |

| Water, plain or flavored | 9 | 2914 | 2917 | 1.46 (0.15) | 1.27 (0.13) | <.0001 |

| Total beverages | 285 | 26300 | 48559 | 234 (6.2) | 239 (6.9) | .0007 |

| Other beverages | 13 | 866 | 883 | 0.47 (0.13) | .043 (0.12) | 0.0938 |

| Yogurt products | 17 | 2263 | 6645 | 10.14 (0.9) | 8.55 (0.69) | <.0001 |

| Cheeses and cheese products | 72 | 9371 | 28817 | 38.99 (2.2) | 38.25 (2.14) | 0.0004 |

| Total beverages, yogurt products, cheese and cheese products | 374 | 37934 | 84021 | 276.54 (6.04) | 279.63 (6.68) | 0.02 |

FNDDS: Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies

WWEIA-NHANES: What We Eat in America, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

USDA: United States Department of Agriculture

Table 2.

Average daily sodium, saturated fat, and total sugars reported consumed from select food groups by applying FNDDS vs. Factory to Fork Crosswalk nutrient profile to WWEIA-NHANES 2007–2008 consumption from stores only (ages 2 years and older, N=8528).

| Sodium (mg/capita/day) | Saturated Fat (g/capita/day) | Total Sugars (g/capita/day) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food/Beverage Group | Applying FNDDS 4.1 |

Applying Crosswalk nutrient profile |

Difference p value |

Applying FNDDS 4.1 |

Applying Crosswalk nutrient profile |

Difference p value |

Applying FNDDS 4.1 |

Applying Crosswalk nutrient profile |

Difference p value |

| Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | ||||

| Coffee/tea | 10.73 (0.58) | 15.81 (1.04) | <.0001 | 0.1 (0.03) | 0.08 (0.01) | 0.4453 | 2.94 (0.3) | 4.02 (0.43) | <.0001 |

| Energy drinks | 4.02 (0.65) | 2.99 (0.38) | 0.0058 | 0 (0.0) | 0.01 (0.0) | 0.0021 | 0.64 (0.1) | .58 (0.08) | 0.0093 |

| Fluid milk | 68.68 (2.84) | 78.7 (3.31) | <.0001 | 1.62 (0.07) | 1.65 (0.07) | <.0001 | 8.18 (0.34) | 7.63 (0.32) | <.0001 |

| Fruit juice | 2.01 (0.11) | 3.53 (0.19) | <.0001 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | <.0001 | 6.33 (0.32) | 6.92 (0.36) | <.0001 |

| Meal replacement beverages | 0.34 (0.18) | 0.22 (0.12) | 0.0608 | 0.05 (0.01) | 0.04 (0.01) | 0.0683 | 0.05 (0.03) | 0.04 (0.02) | 0.116 |

| Soy/Yogurt/Milk-based beverages | 2.78 (0.25) | 3.29 (0.32) | 0.0016 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.4346 | 0.57 (0.09) | 0.50 (0.07) | 0.0176 |

| Sports drinks | 9.42 (1.17) | 10.40 (1.3) | 0.0003 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0126 | 1.38 (0.18) | 1.46 (0.19) | 0.0002 |

| Sugar sweetened beverage | 22.45 (1.25) | 38.08 (2.61) | <.0001 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | <.0001 | 20.10 (1.71) | 23.52 (2.01) | <.0001 |

| Vegetable juice | 10.66 (1.49) | 10.15 (1.37) | 0.1464 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | . | 0.17 (0.02) | 0.14 (0.02) | 0.0065 |

| Water, plain or flavored | 7.42 (0.42) | 1.63 (0.26) | <.0001 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | . | 0.35 (0.04) | 0.31 (0.03) | <.0001 |

| Other beverages | 0.29 (0.09) | 0.35 (0.1) | 0.3059 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.7558 | 0.06 (0.02) | 0.05 (0.01) | 0.0443 |

| Total beverages | 143 (5.0) | 170 (6.0) | <.0001 | 2 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) | 0.8768 | 42 (1.4) | 46 (1.7) | <.0001 |

| Yogurt products | 6.57 (0.56) | 5.81 (0.47) | <.0001 | 0.09 (0.01) | 0.08 (0.01) | 0.0307 | 1.45 (0.11) | 1.19 (0.09) | <.0001 |

| Cheeses and cheese products | 96.38 (4.63) | 98.62 (4.61) | 0.0016 | 1.8 (0.11) | 1.73 (0.1) | <.0001 | 0.35 (0.02) | 0.27 (0.02) | <.0001 |

| Total beverages, yogurt products, cheeses and cheese products | 241.76 (8.33) | 269.58 (9.07) | <.0001 | 3.67 (0.16) | 3.60 (0.15) | .02 | 42.58 (1.25) | 46.64 (1.59) | <.0001 |

FNDDS: Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies

WWEIA-NHANES: What We Eat in America, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

DISCUSSION

The Crosswalk approach augments national nutrition surveys with commercial food and beverage purchases and nutrient databases to capture changes in the US food supply from factory to fork. The Crosswalk provides a comprehensive and representative measurement of the types, amounts, prices, locations, and nutrient composition of CPG foods and beverages consumed in the US and has potential to be a major step forward in understanding the CPG sector of the US food system and the impacts of the changing food environment on human health.

In completing the 2007–08 Crosswalk for beverages, yogurts and cheeses, we identified items within these categories that were purchased by households in the Homescan panel, but did not appear in the WWEIA-NHANES survey. Examples include protein water, almond and rice milks, thickened “milk shake” type beverages, beverage products designed for people with specific medical conditions, and vegetable juice for babies. We found additional examples that were similar to items reported in WWEIA-NHANES but that contained modifications which resulted in significantly different nutritional profiles. For example, tea products with a whitening ingredient (e.g., creamer) such as chai latte mix could be linked based on type of tea and sweetener, but were not ultimately used in the Crosswalk-based nutrient profile due to the additional calories and nutrients from the whitening ingredient. It is important to note that WWEIA-NHANES respondents may have reported the above items yet they were not coded as such given the timing of instrument development and the nature of coding and processing dietary intake survey data.

We identified only five examples of USDA codes that could be not be linked to sufficient bar codes with high quality NFP data from which to develop a Crosswalk-based nutrient profile - fat free parmesan cheese topping, cocoa powder, canned or bottled lemon juice, low calorie fruit flavored drink with high vitamin C made from powdered mix, and dry, unsweetened instant tea.

Comparisons of caloric intake results are not surprising given the reported timing of updates of USDA nutrient information. When examining per capita calories, the largest difference between the two nutrient profiles was for the sugar-sweetened beverage group. This result was anticipated as the nutrient information for the soda category has not been updated since the release of FNDDS 2.0, which corresponds to the What We Eat in America dietary intake survey portion of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (WWEIA-NHANES) 2003–04.

The factory to fork Crosswalk system can also increase our understanding of the impacts of the changing food environment on dietary intake. Recently, manufacturers (e.g., Healthy Weight Commitment Foundation members) and retailers (e.g., Walmart) have begun making pledges to reduce calories, and in some cases also sugars, fats, and sodium from their products.14–16 Using the factory to fork Crosswalk system, we would be able to estimate the impact of these efforts on the diets of Americans.

The factory to fork Crosswalk system provides a framework for improved nutrition monitoring and surveillance of the large, ever evolving CPG sector of our food supply. Resources available for traditional approaches to government monitoring of this dynamic food system have proven insufficient.4,17 The Crosswalk system, which allows for standardized application of nutrient information from commercial data sources to WWEIA-NHANES, is an approach that could also be utilized by the USDA and other governmental bodies to update and maintain national food composition databases.

There are additional surveillance and research needs that could be addressed utilizing the factory to fork Crosswalk system. While it is understood that there are unique race/ethnic subpopulation preferences for various brands, the USDA food composition data does not have brand-specific products and cannot examine dietary profiles sensitive to brand preferences. Through the Crosswalk system we will know the exact brands and products purchased by each subpopulation, and we will be able to use these results to appropriately weight the contribution of various products in order to create subpopulation-specific versions of the Crosswalk nutrient profiles. Furthermore, in addition to nutrients, the commercial nutrient databases contain information on ingredients and additives, as well as all package claims for products. Incorporating this information into the nutrient database would allow for surveillance and research on the complex nature of our changing food supply (e.g., additives, specific allergens, gluten-free products). Finally, using the ingredients and nutrient information our research group is finalizing an approach for estimating nutrients of concern to nutrition professionals that are not currently included on the NFP. We currently utilize a linear programming model similar to that employed by the USDA for analogous purposes18,19 to estimate the added sugars content of products.

Due to the complex nature of this factory to fork effort, there are important limitations. First and foremost are the quality and timeliness of the NFP data. The NFP data do not contain all nutrients and food components of interest to nutrition researchers; however, we believe that those included are of great value. Our group is currently finalizing an approach for estimating added sugar content of products using a linear programming model.

There are likely systematic differences in updating of NFP data, with less popular products being updated less frequently (though also contributing less to overall diets). Additionally, the degree of NFP data accuracy may vary by nutrient and product due to rounding rules and definition of serving size. Furthermore, the 20% labeling measurement allowance between nutrients reported on the NFP and what is found during enforcement analyses and legal reporting rules reduces the precision of NFP data.17 While we currently cannot assess the degree to which these limitations affect our work, the USDA is conducting a detailed, well-sampled full nutrient analysis of the top contributors to sodium in the U.S. The USDA will compare this full nutrient analysis with the NFP for each product to allow assessment of the quality of the NFP data for selected consumer packaged goods. We look forward to this important contribution to the field.

An additional limitation involves the translation of nutrient information from foods and beverages in the ‘as purchased’ form to foods and beverages in the ‘as consumed’ form. We developed a standardized approach by food code that utilizes the food preparation methods per the package instructions in calculating nutrient composition. We acknowledge that this approach limits our ability to account for individual preparations; however we have incorporated the provided modification codes in our analyses to account for individual fat additions.

Upon completion of the 2007–2012 factory to fork Crosswalks, additional research will carefully compare the extent to which the Crosswalk system and current surveillance and monitoring efforts reflect the marketplace.

CONCLUSION

The factory to fork Crosswalk approach augments national nutrition surveys with commercial food and beverage purchases and nutrient data to capture how changes in the US food supply translate to changes in US diets. Our team has successfully developed protocols for standardized linking approaches by food group with extensive discussion with the USDA Food Survey Research Group that develops the FNDDS. This system has the potential to be a major step forward in understanding the CPG sector of the US food system and the impacts of the changing food environment on human health. We are working to complete the entire factory to fork Crosswalk system for 2007–08 and will expand our Crosswalk to include WWEIA-NHANES 2009–2012.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (Grants 67506, 68793, 70017) and the National Institutes of Health (R01DK098072 and CPC 5 R24 HD050924) for financial support. Foremost we thank Dr. Barry Popkin for his conceptualization of this effort. We also wish to thank Dr. Kuo-Ping Li for extensive programming, Ms. Frances L. Dancy for administrative assistance, and Mr. Tom Swasey for graphics support.

Appendix 1. Linking process

After the research team obtains a list of USDA food codes reported consumed in WWEIA 2007–08 as obtained from stores and vending, the team of Registered Dietitians (RDs) reviews the USDA food codes and attempts to group similar USDA food codes together. USDA food codes are grouped together based on various similarities in food form, intended use, production methods, and ingredients. The research team jointly determines appropriate large groups (e.g. cheese, yogurt) and reviews the independently assigned smaller groups (e.g., cottage cheese, mozzarella cheese, cream cheese). The individual RD designs a plan for developing the nutrient profile of NFS or NS (not further specified or not specified, respectively) USDA food codes by combining direct-linked USDA food codes plus any additional bar code unable to be directly linked.

Example: “Cheese, Mozzarella, NFS” would include all bar codes linked to Cheese, Mozzarella, Whole Milk; Cheese, Mozzarella, Part Skim; Cheese, Mozzarella, Low Sodium; Cheese, Mozzarella, Nonfat or Fat Free; and any additional bar codes for which fat or sodium level information was unobtainable.

With the development of the smaller groups and plan for linking, each RD reviews the available bar codes, which are organized into modules based on commercial categorization. The RD reviews all available product attributes, which vary by module but can include: flavor, variety (fat level), food form (sliced, shredded, powder), processing method (spray-dried), packaging (zip-top bag, aerosol can), salt (not salted). The RD reviews each bar code within the appropriate modules and applies one or more appropriate USDA food code links using all available product information including brand name, product description, size, ingredients, and nutrient profile in addition to any previously listed attributes available by module.

Appendix 2. Preparation factors for converting nutrient information from beverages as purchased into nutrient information for beverages as consumed

Powder concentrate form

Beverage products in powder concentrate form required addition of various ingredients—primarily water, milk, and sugar. Preparation factors were coded as “grams of ingredient per gram of product”. The adjusted per 100g nutrients account for the change in volume, as well as the change in nutrients resulting from the ingredients added. Nutrients from ingredients were based on the USDA Standard Reference (SR). For example, a product requiring addition of 2% milk would receive a preparation factor indicating addition of a specific amount of SR Code 01079 Milk, reduced fat, fluid, 2% milkfat, with added vitamin A and vitamin D.

Liquid concentrate form

Beverage products in liquid concentrate form required addition of water in mL (1mL = 1g). The product package size was multiplied by a “food form factor” that yielded the volume of ready-to-drink beverage, and the nutrients per 100mL were adjusted accordingly. In order to convert mL to g, “density factors” were created based on the weight for a given volume of a beverage from the FNDDS; therefore, density factors were specific to the USDA food code, and all products linked to a given USDA food code received the same density factor. For example, for code 61210620 Orange Juice, frozen (reconstituted with water), 8 fluid ounces (236.588 mL) is equivalent to 249 g. We divide 249 g by 236.588 fluid ounces to calculate the density factor: 1.052 g/mL. Dividing the nutrients per 100 mL by 1.052 g/mL yields the nutrients per 100 g.

Ready-to-drink form

Beverage products in ready-to-drink form required conversion from mL to g by density factor, described above. No other adjustments were needed.

Footnotes

None of the authors have conflict of interests of any type with respect to this manuscript.

Funding Disclosure

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (Grant 70017)

National Institutes of Health (R01DK098072)

Carolina Population Center (5 R24 HD050924)

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ng SW, Slining MM, Popkin BM. Use of caloric and noncaloric sweeteners in US consumer packaged foods, 2005–2009. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(11):1828–1834. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKinnon R, Reedy J, Handy S, Rodgers A. Measuring the food and physical activity environments: shaping the research agenda. Am J Prev Med. 2009 Apr;36(4 Suppl):S81–85. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Collaborative on Childhood Obesity Research N. Farm to Fork Workshop on Surveillance of The U.S. Food System; 2012; Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Institute of Medicine I. Measuring Progress in Obesity Prevention: Workshop Report; 2012; Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Slining MM, Ng SW, Popkin BM. Food companies’ calorie-reduction pledges to improve U.S. diet. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(2):174–184. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.09.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ng SW, Popkin BM. Monitoring foods and nutrients sold and consumed in the United States: Dynamics and challenges. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(1):41–45. e44. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Einav L, Leibtag E, Nevo A. Recording discrepancies in Nielsen Homescan data: Are they present and do they matter? Quant Market Econ. 2010;8(2):207–239. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhen C, Taylor JL, et al. Understanding differences in self-reported expenditures between household scanner data and diary survey data: A comparison of homescan and consumer expenditure survey. Rev Ag Econ. 2009;31(3):470–492. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Einav L, Leibtag E, Nevo A. On the Accuracy of Nielsen Homescan Data, Economic Research Report 69. Washington, DC: Economic Research Services, USDA; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aguiar M, Hurst E. Life-cycle prices and production. Am Econ Rev. 2007;97(5):1533–1559. [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Archives and Records Administration. CFR 21, 101.9. Washington, DC: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 12.USDA, ARS, Nutrient Data Laboratory. USDA national nutrient database for standard reference, release 22. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13.USDA; Department of Agriculture ARS, Food Survey Research Group, editor. Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies, 4.1. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Healthy Weight Commitment Foundation. Healthy Weight Commitment Foundation, Fact Sheet. Washington DC: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Healthy Weight Commitment Foundation. Food and Beverage Manufacturers Pledging to Reduce Annual Calories By 1.5 Trillion By 2015. Press Release 2010. 2010 May 17; http://www.healthyweightcommit.org/news/Reduce_Annual_Calories/

- 16.Walmart. Walmart Launches Major Initiative to Make Food Healthier and Healthier Food More Affordable. 2011 http://walmartstores.com/pressroom/news/10514.aspx.

- 17.Improving Data to Analyze Food and Nutrition Policies. National Research Council; 2005. Panel on Enhancing the Data Infrastructure in Support of Food and Nutrition Programs Research and Decision Making. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Westrich BJ, Buzzard IM, Gatewood LC, McGovern PG. Accuracy and efficiency of estimating nutrient values in commercial food products using mathematical optimization. J Food Compos Anal. 1994;7(4):223–239. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schakel SF, Buzzard IM, Gebhardt SE. Procedures for estimating nutrient values for food composition databases. J Food Compos Anal. 1997;10(2):102–114. [Google Scholar]