Abstract

Objective

Postprandial lipemia worsens after menopause, but the mechanism remains unknown. We hypothesized menopause-related postprandial lipemia would be: 1) associated with reduced storage of dietary fatty acids (FA) as triglyceride (TG) in subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT); and 2) improved by short-term estradiol (E2).

Design and Methods

We studied 23 pre- (mean±SD; 42±4yr) and 22 postmenopausal (55±4yr) women with similar total adiposity. A subset of postmenopausal women (n=12) were studied following 2 weeks of E2 (0.15mg) and matching placebo in a random, cross-over design.

A liquid meal containing 14C-oleic acid traced appearance of dietary FA in: serum (postprandial TG), breath (oxidation), and abdominal and femoral SAT (TG storage).

Results

Compared to premenopausal, healthy lean postmenopausal women had increased postprandial glucose and insulin and trend for higher TG, but similar dietary FA oxidation and storage. Adipocytes were larger in post- compared to premenopausal women, particularly in femoral SAT. Short-term E2 reduced postprandial TG and insulin, but had no effect on oxidation or storage of dietary FA. E2 increased the proportion of small adipocytes in femoral (but not abdominal) SAT.

Conclusions

Short-term E2 attenuated menopause-related increases in postprandial TG and increased femoral adipocyte hyperplasia, but not through increased net storage of dietary FA.

Introduction

Subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) buffers the flux of triglycerides (TG) after a meal1. Impaired uptake of dietary fatty acids (FA) into SAT may contribute to cardiometabolic risk through increases in postprandial TG and ectopic (e.g., visceral, hepatic, intramuscular) TG accumulation1. Women prior to menopause have more SAT and greater TG clearance (less postprandial lipemia) compared to men2, 3. After menopause postprandial TG clearance is reportedly reduced compared to premenopausal women, independent of differences in body mass index (BMI)4. These observations suggested sex hormones might play a role in postprandial TG clearance. Indeed, 6wks of estradiol (E2) treatment appeared to improve TG clearance in postmenopausal women5, but the mechanism is unknown. Potential mechanisms for increasing TG clearance include: delayed absorption of dietary FA, increased oxidation of dietary FA, reduced secretion of very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL)-TG, and increased storage of dietary FA as TG. Compared to men, premenopausal women appeared to store more dietary FA in SAT and this was associated with less TG storage elsewhere (visceral fat, liver, skeletal muscle)6. Consistent with this, postprandial lipemia was associated with greater visceral adiposity in premenopausal women7. Dietary fat oxidation may also be greater in women compared to men8, although this is not a consistent finding3. It is not known whether there are menopause-related reductions in the oxidation or storage of dietary FA, but if so this might contribute to the observed increases in postprandial lipemia and ectopic (depots other than SAT) fat accumulation after menopause. We hypothesized that, compared to premenopausal women, postmenopausal women would have reduced postprandial TG clearance and a smaller proportion of meal-derived FA being oxidized and stored as TG in SAT. We postulated the reduced uptake of dietary FA by SAT would be associated with increased storage elsewhere (i.e., not accounted for in SAT). We further hypothesized that treating postmenopausal women with E2 would improve storage of meal-derived FA in SAT TG and mitigate menopause-related differences in postprandial lipemia and ectopic storage.

Methods

Subjects

We studied 23 premenopausal (35–50yr) and 22 postmenopausal (48–60yr) women of similar total adiposity. All women were healthy, non-obese (BMI<30 kg/m2), non-smokers, and sedentary to moderately physically active (exercise ≤150min/wk). Premenopausal women were normally menstruating (25–35 day cycles) and postmenopausal women were amenorrheic (≥1yr) or had undergone bilateral oophorectomy (FSH>30 IU/L). None of the women were currently (≤3mos) using estrogen-based hormones and none used lipid- or glucose-lowering medications. Women were excluded if they were not weight stable (±2kg over past 2mo) or had any metabolic or cardiovascular disease. Prior to enrollment, each woman provided informed consent. The protocol was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board.

Body composition assessment

Total and regional (trunk, leg) fat mass (FM) and fat-free mass (FFM) were measured by DXA (Hologic Discovery W, software version 11.2) as previously described9. CT scans of the abdomen (L2–L3 and L4–L5) and mid-thigh measured abdominal and femoral subcutaneous fat areas (SFA, cm2) as previously described10. Visceral fat area (VFA, cm2) and intermuscular fat area (IMFA) were calculated as the difference between total and subcutaneous fat areas. Visceral and subcutaneous FM (kg) were estimated as previously described11. The proportions of visceral and subcutaneous FM were multiplied by trunk FM and intermuscular and subcutaneous FM were multiplied by leg FM to estimate the proportions in the upper and lower body, respectively.

Physical activity assessment

The Yale Physical Activity Survey12 was administered to assess time spent in a range of activities. Total time (hours/week) for each activity was multiplied by the intensity code (kcals/hour) provided by the survey and the sum of all activities (adjusted for season) used to estimate the energy expenditure (EE) of daily activities (kcal/day).

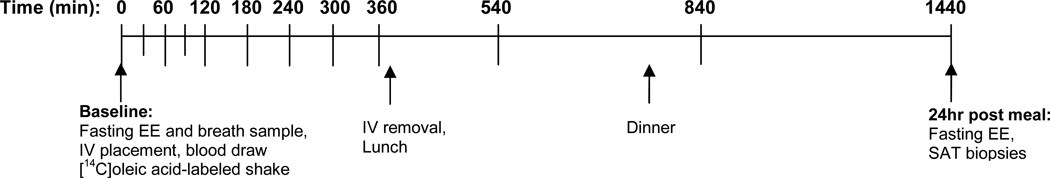

Test Meal visit (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Schematic timeline for 24-hour test meal visit. Fasting and postprandial blood samples (14C-TG), breath samples (14CO2) and indirect calorimetry (energy expenditure) measures were collected at each time point.

Subjects consumed a 3-day standardized diet [Kcal=(23.9*FFM+372)*1.5]13 prepared by the Clinical Translational Research Center (CTRC) metabolic kitchen. Following an overnight fast, volunteers were admitted to the CTRC. Premenopausal women were studied during the follicular phase of their menstrual cycle (day 1–10). Resting EE was measured, breath samples were collected (described below), and an antecubital IV catheter was placed. After baseline sample collection volunteers consumed a liquid test meal (Boost Plus®, heavy cream, whey protein, and sugar) providing one third of estimated daily energy requirements containing 50% carbohydrate, 34% fat (13%saturated/13.5%monunsaturated/7.5%polyunsaturated) and 16% protein and labeled with 40µCi of [1- 14C]oleic acid (Moravek Biochemicals). The composition of the test meal matched the composition of the lead-in diet. Blood was sampled at T = 0, 30, 60, 90, 120, 180, 240, 300, and 360 min for the assessment of 14C, TG, free fatty acids (FFA), glucose, and insulin. Urine was collected for N2 excretion. Subjects consumed a standardized lunch and dinner consisting of one third each of their daily energy requirements and then remained fasted overnight on the CTRC.

Energy expenditure and substrate oxidation

Resting and postprandial EE was measured by indirect calorimetry (Parvo Medics TrueOne 2400)14. Breath CO2 samples were collected by having subjects exhale through a one-way filter into a scintillation vial containing 0.5mL benzethonium hydroxide (to trap 0.5mM CO2), 2mL absolute methanol and 0.5mL phenolphthalein3. EE was measured and breath samples collected at T = 0, 60, 120, 180, 240, 300, 360, 540, 840, and 1440 min. Total fat and carbohydrate oxidation were calculated from CO2 production, O2 consumption, and urinary N2 excretion as previously described15. 14CO2 production (dpm/min) was calculated by multiplying the VCO2 production (mL/min) by the breath specific activity (14CO2, dpm/mmol) and 1mmol CO2/22.4mL. The amount of 14C-oleic acid oxidized was calculated from the 24hr area under the curve (AUC) for 14CO2 divided by the 14C ingested.

Separation of lipid fractions

Blood samples collected at T=0, 60, 120, 180, 240, and 360 min were added to chilled EDTA-containing tubes and immediately spun (3,000 rpm, 10 min, 4 °C). Fresh plasma (2mL) was placed into polycarbonate tubes with NaN3 (10%, 2uL) and PMSF (10mmol/L, 20uL) added to stabilize the triglyceride rich lipoproteins (TRL). Within 24hrs plasma was separated into TRL sub-fractions using a sequential floatation, ultracentrifugation method (large Svedberg flotation [Sf] >400, and medium Sf 20–400)16. The large sub-fraction consists primarily of chylomicron (CM) particles with small amounts of larger VLDL particles. The medium sub-fraction consists primarily of VLDL lipoproteins and some smaller CM particles. For collection of the large TRL, plasma was centrifuged (100,000 rpm, 10 min, 15 °C; Beckman TLX100), allowed to sit (1hr), and the supranate removed. For collection of the medium TRL, the infranate was overlaid with 1.0ml of NaCl solution (1.006 g/ml density) and centrifuged (100,000rpm, 2.5hr, 15 °C), allowed to sit (1hr), and the supranate removed. 14C radioactivity was immediately assessed in each sub-fraction at each time point and the remaining sample stored at −80 °C for measurement of TG concentrations.

Adipose tissue biopsies

24h after the test meal, biopsies were taken from the abdominal and femoral SAT depots using a mini-liposuction suction technique as previously described17. Previous studies have shown that peak rate of uptake of dietary TG occurs approximately 4–6 hours after a meal, whereas uptake is near maximal by 24hrs18. Thus biopsies were done at 24h to determine net uptake of meal FA. Adipocyte cellularity and lipoprotein lipase (LPL, described below) activity were determined on an aliquot of fresh SAT sample and the remaining tissue frozen for later analysis of 14C specific activity (SA).

Adipocyte cellularity

Immediately after collection, SAT was digested in Krebs-Ringer phosphate buffer containing collagenase (3 mg/ml) in 37°C shaking water bath for 30min. Average adipocyte size (552±288 cells/sample) was determined as previously described19, 20. In brief, collagenase-released adipocytes were stained with methylene blue and imaged (Olympus BX60 microscope, Canon Power Shot G5 digital camera) and counted with Cell Counting Analysis Program (CCAP; Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN).

Adipose tissue LPL activity

Immediately after collection, heparin-releasable LPL activity (nmol FFA/min/g) was measured in fresh abdominal and femoral SAT samples as previously described21. Briefly, LPL was eluted from SAT fragments (~40 mg) into Krebs-Ringer phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing heparin (15 µg/mL). Enzyme activity was measured as hydrolyzed [14C]- or [3H]-oleic acid after incubation with a synthetic substrate.

14C in adipose tissue and breath

Radioactivity in SAT was determined by liquid scintillation counting (LS6000TA; Beckman Instruments). Lipid was extracted from the SAT samples22 and radioactivity was counted (20min/ea) to a counting error <5% as described previously23. Specific activity (SA; dpm/g) in the abdominal and femoral SAT samples was multiplied by trunk and leg FM to calculate upper body (UBSQ) and lower body (LBSQ) subcutaneous TG storage. 14CO2 SA was measured in breath samples to determine fat oxidation. Ectopic TG storage was estimated from 14C not accounted for in oxidation or SAT storage as previously described24.

Estradiol treatment

The Test Meal visit was performed on two occasions in a subset of 12 postmenopausal women following 2 weeks of transdermal E2 (0.15mg; 3 × 0.05mg patches) and matching placebo patches in a random, cross-over manner. An average of 8±1 weeks separated the two tests; long enough for wash-out of E2 but short enough for weight stability.

Blood analyses

Blood samples were stored at −80°C and analyzed in batch by the CTRC Core Laboratory. Glucose, TG (Beckman Coulter, Inc.), and FFA (Wako Chemicals, Inc.) were determined enzymatically; insulin, leptin, and adiponectin by radioimmunoassay (EMD Millipore, Corp.); and estradiol and sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) by chemiluminescence (Beckman Coulter, Inc.). Sensitivity and precision details can be found at http://cctsi.ucdenver.edu/Research-Resources/CTRCs/Pages/Assays.aspx.

Statistics

The integrated AUC for postprandial (0–6 hours) outcomes (e.g, TG, glucose, insulin, substrate oxidation) were calculated by the trapezoidal method. Incremental AUC (IAUC) was determined to account for basal (fasting) concentrations. Statistical power (79%, α=0.05) for this study (with n= 23/group) was estimated from a previous study which reported a mean group difference and SD in TGIAUC of 1.5±1.8 mmol*h/L (133±159mg*h/dL) between pre- and postmenopausal women4. Menopause-related group differences and E2-mediated changes in outcomes were evaluated by one-way and repeated measures analysis of variance, respectively. All statistical analyses were done in SPSS (version 21, IBM Corporation). Data are presented as mean±SD unless otherwise specified.

Results

Subject Characteristics (Table 1)

Table 1.

Subject characteristics

| Premenopausal Women |

Postmenopausal Women |

Postmenopausal E2 subgroup |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| (n=23) | (n=22) | (n=12) | |

| Age (yrs) | 42 ± 4 | 55 ± 4* | 56 ± 3 |

| Years past menopause | n/a | 7 ± 5 | 6 ± 5 |

| Weight (kg) | 67.7 ± 8.4 | 62.1 ± 8.2* | 64.2 ± 9.9 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.2 ± 2.6 | 23.3 ± 2.4 | 24.1 ± 2.5 |

| Fat mass (kg) | 22.7 ± 5.3 | 21.7 ± 5.3 | 23.5 ± 5.5 |

| %Fat | 33.3 ± 4.8 | 34.5 ± 5.2 | 36.3 ± 4.3 |

| Trunk fat mass (kg) | 9.2 ± 2.6 | 9.7 ± 3.5 | 11.1 ± 3.6† |

| Leg fat mass (kg) | 10.4 ± 2.5 | 8.8 ± 1.7* | 9.0 ± 1.9 |

| Fat-free mass (kg) | 44.9 ± 4.6 | 40.5 ± 4.7* | 40.7 ± 5.5 |

| Abdominal SFA (cm2) | 228.6 ± 62.2 | 221.5 ± 70.5 | 247.2 ± 74.4 |

| Femoral SFA (cm2) | 212.3 ± 58.3 | 173.1 ± 39.7* | 173.5 ± 35.6 |

| VFA (cm2) | 41.2 ± 24.7 | 57.6 ± 40.9 | 74.8 ± 40.2† |

| Femoral IMFA (cm2) | 16.6 ± 9.3 | 15.4 ± 5.8 | 16.0 ± 7.1 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 83 ± 8 | 87 ± 8 | 83 ± 6 |

| Fasting insulin (uU/mL) | 8 ± 3 | 9 ± 4 | 11 ± 4 |

| Estradiol (pg/mL) | 91 ± 76 | 14 ± 6* | 108 ± 65† |

| SHBG (nM/L) | 64 ± 22 | 60 ± 25 | 66 ± 20† |

| Leptin (ng/mL) | 13 ± 6 | 12 ± 7 | 17 ± 10† |

| Adiponectin (ug/mL) | 15 ± 5 | 17 ± 9 | 15 ± 8 |

p<0.05 vs premenopausal;

p<0.05 vs postmenopausal untreated.

BMI, Body Mass Index; E2, estradiol; IMFA, intermuscular fat area by CT; SFA, subcutaneous fat area by CT; SHBG, sex hormone binding globulin; VFA, visceral fat area by CT. Subgroup body composition data describe baseline (pre-E2) characteristics; serum hormones and adipokines are the results of 2 weeks of transdermal E2 treatment.

The postmenopausal women were on average 10 years older than the premenopausal women. The pre- and postmenopausal groups were recruited to have similar total adiposity, but this resulted in postmenopausal women having less FFM and leg FM than the premenopausal women (p<0.05). Trunk FM and visceral adiposity were not different between the groups. The sub-group of 12 postmenopausal women enrolled in the transdermal E2 treatment arm of the study had more visceral adiposity, but similar FFM and leg FM compared to the rest of the postmenopausal cohort. There were no differences in total daily activity EE between pre- and postmenopausal women (1212±946 vs. 1229±588 kcal/day, respectively) or the E2 sub-group (1276±673 kcal/d).

Menopause-related differences

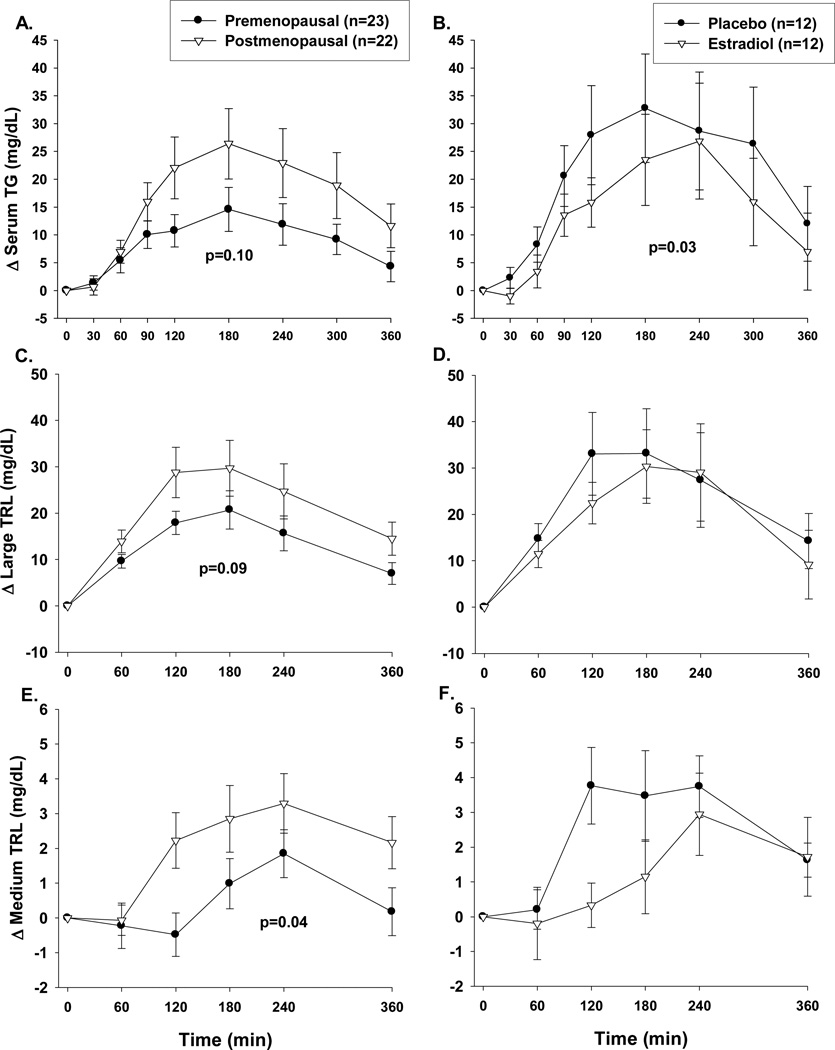

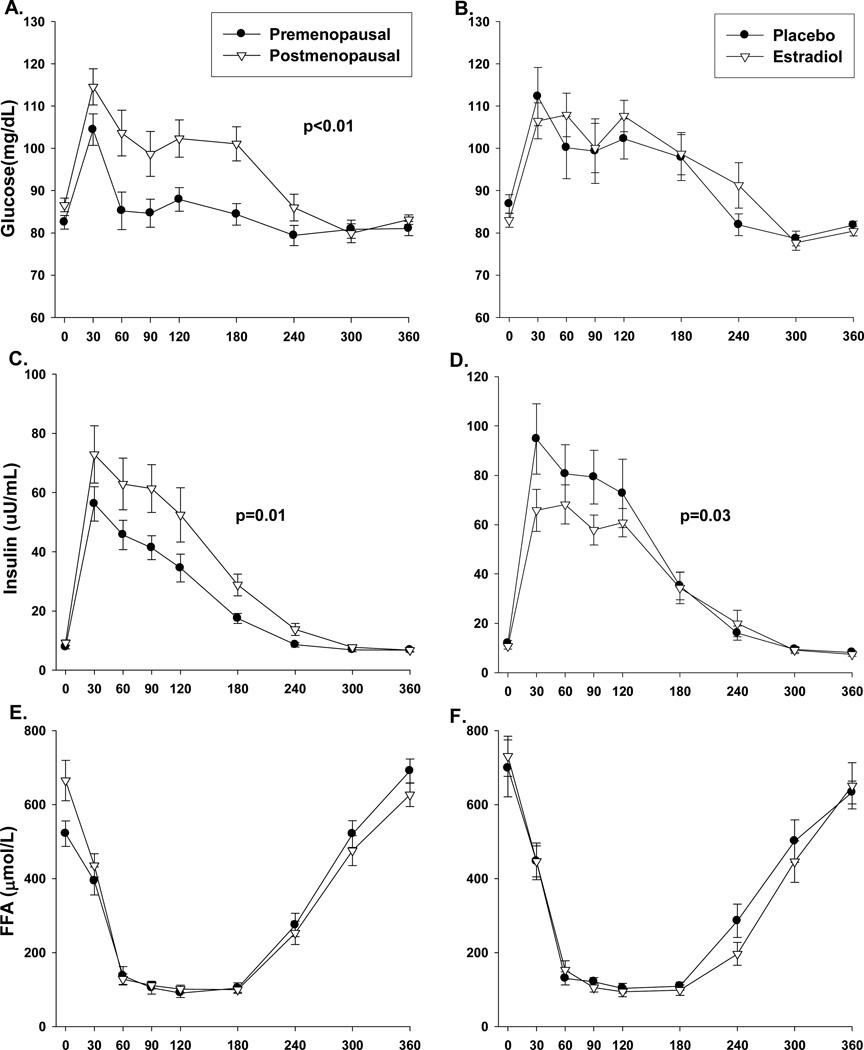

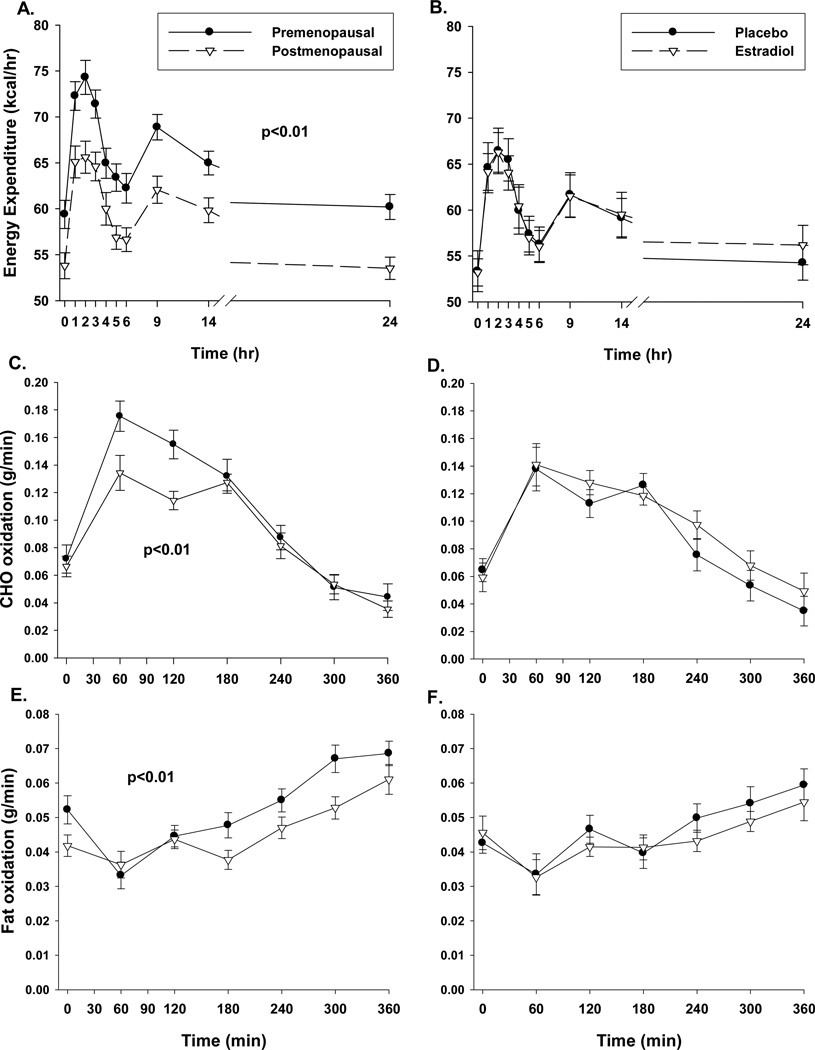

Compared to premenopausal women, postmenopausal women had a trend for higher total postprandial TG (TGIAUC 6405±1482 vs. 3885±685, p=0.10; Figure 2A), due to less suppression of VLDL-TG (Figure 2E, p<0.05) and a trend for reduced clearance of CM-TG (Figure 2C, p=0.09). 14C in the TRL sub-fractions did not differ between groups (data not shown), suggesting no difference in dietary FA appearing in CM and VLDL fractions. The postprandial TG excursions were accompanied by greater (p≤0.01) postprandial glucose and insulin excursions in post- compared to premenopausal women (Figures 3A and 3C, respectively). Postmenopausal women had lower (p<0.01) total AUC for 24-hr EE and 6-hr postprandial total carbohydrate and fat oxidation (Figures 4A, 4C and 4E). However, the lower EE and substrate utilization in postmenopausal compared to premenopausal women was directly related to their lower lean mass, as these group differences were not significant after adjustment for FFM (data not shown). There were no differences between pre- and postmenopausal women in the oxidation or net storage (relative or absolute) of dietary FA into abdominal or femoral SAT or elsewhere (Table 2). However, there were significant menopause-related differences in mean adipocyte size (Table 2). These differences were due to more large adipocytes (101–140µm) in the femoral (p<0.05), and a trend in the abdominal (p=0.12), region. Postmenopausal women also tended to have fewer small (21–60 µm) abdominal (p=0.12) and medium (61–100µm) femoral (p=0.12) adipocytes compared to premenopausal women. LPL activity was not different between groups (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Postprandial (6hr) responses in pre- (n=23) and postmenopausal (n=22) women or postmenopausal women (n=12) treated with and without 2 weeks of estradiol for: total serum triglycerides (panels A and B); large buoyant (Sf>400; primarily chylomicron) triglyceride rich lipoprotein (TRL) particles (panels C and D); and medium (Sf 20–400; primarily VLDL).) TRL particles (panels E and F). P-value for group difference in area under the curve.

Figure 3.

Postprandial (6hr) responses in pre- (n=23) and postmenopausal (n=22) women or postmenopausal women (n=12) treated with and without 2 weeks of estradiol for: plasma glucose (panels A and B); insulin (panels C and D); and free fatty acids (panels E and F). P-value for group difference in area under the curve.

Figure 4.

Twenty four hour energy expenditure (panels A and B), postprandial fat oxidation (panels C and D) and carbohydrate (CHO) oxidation (panels E and F) in pre- (n=23) and postmenopausal (n=22) women or postmenopausal women (n=12) treated with and without 2 weeks of estradiol. P-value for group difference in area under the curve.

Table 2.

Tissue cellularity, LPL activity and storage of dietary fatty acid

| Premenopausal Women |

Postmenopausal Women |

Postmenopausal Placebo |

Postmenopausal E2 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meal-derived fatty acid trafficking (relative) | ||||

| Oxidized (%) | 25.7±7.3 | 23.6±7.4 | 22.1±9.2 | 23.3±4.2 |

| Upper body SAT (%) | 14.7±7.6 | 12.3±7.3 | 11.4±6.0 | 11.9±4.0 |

| Lower body SAT (%) | 10.4±5.8* | 10.2±10.5* | 5.7±3.4* | 8.3±6.5* |

| Ectopic (%) | 50.1±13.6 | 54.4±14.1 | 60.6±11.3 | 55.9±95 |

| Meal-derived fatty acid uptake (absolute) | ||||

| Upper body SAT (mg meal TG/ g Tissue) | 0.35±0.17 | 0.35±0.26 | 0.25±0.16 | 0.29±0.12 |

| Lower body SAT (mg meal TG/ g Tissue) | 0.27±0.14* | 0.29±0.26* | 0.16±0.10* | 0.22±0.13* |

| Abdominal adipocyte size | ||||

| Mean diameter (µm) | 45.0±12.2 | 55.1±19.4** | 66.1±18.8 | 61.9±13.0 |

| %small (21–60µm) | 51.3±17.7 | 41.0±24.3+ | 26.5±18.6 | 32.9±17.6 |

| %medium (61–100µm) | 45.4±17.6 | 50.9±20.9 | 61.2±17.7 | 57.8±18.5 |

| %large (101–140µm) | 3.3±5.1 | 8.2±13.6+ | 12.3±17.1 | 9.3±11.2 |

| Femoral adipocyte size | ||||

| Mean diameter (µm) | 50.8±12.9 | 61.6±21.0** | 76.1±16.5 | 56.9±18.7+ |

| %small (21–60µm) | 42.2±15.9 | 39.9±17.8 | 21.8±17.9 | 45.2±23.2† |

| %medium (61–100µm) | 49.8±16.1 | 41.3±20.1+ | 49.0±16.3 | 41.9±19.6+ |

| %large (101–140µm) | 8.0±7.0 | 18.8±20.2** | 29.3±22.8 | 12.9±11.9+ |

| LPL activity | ||||

| Abdominal (nmol/g/min) | 13.9±9.0 | 14.4±9.7 | 17.1±10.4 | 19.0±12.9 |

| Femoral (nmol/g/min) | 36.1±25.5* | 38.4±31.2* | 41.4±37.0* | 34.0±24.1* |

mean±SD;

p<0.05 lower body different from upper body;

p<0.05 postmenopausal different from premenopausal;

p≤0.05 E2 treated different from placebo;

p≤0.12 trend for group difference.

LPL, lipoprotein lipase; SAT, subcutaneous adipose tissue; TG, triglyceride.

Differences in regional SAT depots

There were consistent depot-specific differences in SAT among pre- and postmenopausal women. Irrespective of group, less absolute and relative (Table 2) dietary FA was stored in lower versus upper body SAT. There was a trend (p=0.11) for mean cell diameter to be larger in the femoral region compared with the abdominal region in all women. Cell size was inversely related to dietary FA uptake in the femoral (r=−487, p≤0.001), but not abdominal (r=−0.186, p=0.26), region. Higher leptin concentrations were associated with a greater proportion of large adipocytes in abdominal SAT (r=0.460, p<0.01) and a lesser proportion of medium adipocytes in the femoral region (r=−0.342, p<0.05). LPL activity was consistently higher in femoral than abdominal SAT (p<0.01; Table 2) in both groups. Abdominal and femoral LPL activity were associated with mean cell size in abdominal (r=0.591, p<0.01) and femoral (r=0.317, p=0.05) SAT, respectively.

Acute effects of estradiol

Compared with placebo, 2 weeks of E2 increased serum leptin (Table 1), reduced postprandial TG and insulin responses (Figures 2B and 3D; p<0.05), but had no effect on postprandial EE or nutrient oxidation (Figure 4B,D,F). E2 did not alter the proportion of dietary FA that were oxidized or stored in SAT versus other depots (Table 2). Compared with placebo, E2 did not change LPL activity in abdominal or femoral SAT. However, acute E2 increased the percentage of small adipocytes (p<0.05) and tended to reduce the percentage of medium (p=0.11) and large adipocytes (p=0.06) in femoral, but not abdominal, SAT.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that healthy lean postmenopausal women tended to have higher postprandial TG, and significantly higher glucose and insulin, compared to premenopausal women; treatment with short-term (2 wks) E2 reduced postprandial TG and insulin. In contrast to our hypothesis, there was no effect of menopause or E2 on the oxidation or storage of dietary FA. There were region-specific and menopause-related differences in adipocyte size such that adipocytes were larger in femoral SAT in post- compared to premenopausal women. Short-term administration of E2 to postmenopausal women increased serum leptin and the proportion of small adipocytes in the femoral region. Among all women, smaller adipocytes were associated with greater uptake of dietary FA by femoral SAT.

Sex hormones and postprandial lipemia

Fasting plasma TG concentrations are a risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD), particularly in women compared to men25. Postprandial TG may be an even better indicator of CVD risk because it is an integrated measure26 of CM-TG clearance and VLDL-TG appearance and indicative of TG delivery to ectopic depots. Previous studies demonstrated that prior to menopause women have a blunted postprandial TG when compared to men2, 3, but this advantage may be lost after menopause4. One study also suggested that E2 treatment reduced postprandial lipemia in postmenopausal women, possibly through an increase in CM-TG clearance5. These preliminary observations suggested a role for sex hormones in postprandial TG clearance which our data generally supported. We extended these observations by testing one mechanism for increasing postprandial TG clearance, increased storage of dietary FA in SAT.

Sex hormones and dietary fatty acids

Early studies in women and men suggested a link between SAT storage of dietary FA, visceral adiposity, and postprandial lipemia. Sex differences in the proportion of dietary FA going to SAT versus elsewhere (i.e., ectopic) were reported6, although not consistently3. Among women, variability in SAT storage appeared to explain the association between postprandial lipemia and abdominal adiposity7. However, a more recent study disassociated TG clearance and SAT storage; postprandial TG was elevated in postmenopausal, compared with premenopausal, women despite their storing a greater proportion of dietary FA in SAT27. Consistent with this, our study did not support a causal association between storage of dietary FA and postprandial TG clearance. Postprandial TG excursions were greater in postmenopausal, compared to premenopausal, women but storage of dietary FA in SAT was not different. Moreover, the greater TG response was accompanied by less suppression of VLDL-TG secretion. The fact that short-term E2 improved TG clearance without a change in TG-FA storage provided further evidence that the mechanism by which sex hormones reduce postprandial lipemia is not through an increase in dietary FA storage.

Sex hormones and fat oxidation

Reduced oxidation of dietary fat is another mechanism by which postprandial lipemia might worsen. Dietary fat oxidation has been shown to be greater in women compared to men8, although not consistently3. We did not observe a menopause-related difference in the proportion of dietary fat oxidized (14C in CO2) but total fat and carbohydrate oxidation during the 6 hour postprandial period were lower in postmenopausal women, consistent with previous observations27. The lower substrate oxidation was consistent with the overall reduction in resting EE and appropriate for their lower FFM. Treating postmenopausal women with E2 for 2 weeks had no effect on EE or substrate oxidation (dietary or total). Thus, reductions in fat oxidation did not explain group differences in postprandial TG.

Sex hormones and adipose tissue cellularity

There are region-specific sex differences in adipocyte cellularity. Compared to men, women have larger adipocytes in the femoral regions but smaller or similarly sized adipocytes in the abdominal (subcutaneous and visceral) regions28, 29. These sex- and region-specific differences in adipocyte size lead to different responses to overfeeding; femoral adipocytes increasing in cell number (hyperplasia) and abdominal adipocytes increasing in size (hypertrophy)30. In the present study, adipocytes were larger in postmenopausal compared to premenopausal women, particularly in the femoral region which responded to short-term E2 treatment with an increase in the proportion of small adipocytes.

Sex hormones and adipose tissue LPL

Adipose tissue LPL hydrolyzes circulating TG to facilitate storage of FA in adipocytes. LPL activity is generally correlated with cell size and varies by sex and fat depot29. In the present study, LPL was related to cell size, but fasting abdominal and femoral SAT LPL activity (per gram) was not different between groups or in response to short-term E2. Adjusting for differences in cell size (by analysis of covariance) did not change the results (data not shown). Our data are consistent with earlier studies which found no differences in abdominal LPL activity between pre- and postmenopausal women31 or in response to percutaneous E2 treatment32.

Regional adipose tissue differences

Femoral SAT is metabolically distinct from abdominal SAT. The half-life of TG (net turnover) appears to be 50% longer in femoral compared to abdominal SAT33, 34. This slower turnover of TG in femoral SAT is consistent with the concept that this depot may be a relatively more effective sink for holding onto TG1. That said, in the current study proportionally less dietary FA was incorporated into the femoral than abdominal TG stores over a 24-hour period, suggesting the longer half-life for TG in this depot is due to slower mobilization rather than greater assimilation. Given that fasting LPL activity was higher in femoral compared to abdominal SAT, enzyme availability did not explain the lower femoral uptake of dietary FA. In the present study, femoral adipocytes were larger and the depot more sensitive to acute E2 (responding with hyperplasia), compared to the abdominal depot, but whether this impacted TG clearance remains unclear.

Study Limitations

It is important to point out limitations to our study. First, we studied normal-weight women matched for total adiposity. Matching for total adiposity allowed a fair comparison of total and relative uptake of dietary FA into SAT, but the resulting group differences in FFM lead to net differences in EE and substrate oxidation. Second, our women were non-obese and normolipidemic and E2 treatment was short-term (2 wks). This cohort and study design allowed us to evaluate the effect of menopause and E2 independent of obesity or changes in adiposity. However, the healthy cohort likely explains why differences in postprandial TG between groups were smaller than previously reported. The TG lowering effect of E2 may have been more apparent in postmenopausal women with hypertriglyceridemia and treated for a longer period of time. It is also possible that peak rate of TG storage at 6hr, rather than net storage at 24hr, would have better reflected postprandial TG clearance. However, it is unlikely these limitations explain the lack of an effect of menopause or E2 on the trafficking of dietary FA.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that menopause-related increases in postprandial TG and insulin are attenuated with acute E2 administration. There were no effects of menopause or E2 on oxidation or storage of dietary FA. In the femoral region adipocytes were larger in postmenopausal, compared to premenopausal, women and short-term E2 attenuated these differences. Taken together these data suggest that the loss of endogenous sex hormones at menopause and the addition of exogenous E2 impact postprandial clearance of TG through mechanisms independent of subcutaneous adipose tissue dietary FA uptake.

What is already known about this subject.

Postprandial triglycerides are increased in postmenopausal compared to premenopausal women.

Estradiol has been shown to reduce postprandial triglycerides in postmenopausal women.

What this study adds

Menopause-related differences and estradiol-mediated effects on postprandial triglyceride clearance did not appear to be mediated through subcutaneous adipose tissue storage of dietary fat.

Short-term estradiol in postmenopausal women did not appear to increase storage of dietary fat in subcutaneous adipose tissue triglyceride.

Short-term estradiol in postmenopausal women increased serum leptin and promoted femoral adipocyte hyperplasia.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the staffs of the UCD-Anschutz Medical Campus Clinical Translational Research Center (CTRC), Department of Radiology, and Energy Balance Core of the Nutrition and Obesity Research Unit (NORC) for their assistance in conducting this study. The authors would also like to thank the members of their research group for carrying out the day-to-day activities of the project and the study volunteers for their time and efforts. The following awards from the National Institutes of Health supported this research: DK077992, DK088105, DK002935, AG000279, DK038088, HD057022, P30 DK048520, UL1 TR000154

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Frayn KN. Adipose tissue as a buffer for daily lipid flux. Diabetologia. 2002;45:1201–1210. doi: 10.1007/s00125-002-0873-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Couillard C, Bergeron N, Prud'homme D, Bergeron J, Tremblay A, Bouchard C, et al. Gender difference in postprandial lipemia: Importance of visceral adipose tissue accumulation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19(10):2448–2455. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.10.2448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horton TJ, Commerford SR, Pagliassotti MJ, Bessesen DH. Postprandial leg uptake of triglyceride is greater in women than in men. Am J Physiol: Endocrin Metab. 2002;283(6):E1192–E1202. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00164.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Beek AP, de Ruijter-Heijstek FC, Erkelens DW, de Bruin TW. Menopause is associated with reduced protection from postprandial lipemia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19(11):2737–2741. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.11.2737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Westerveld HT, Kock LA, van Rijn HJ, Erkelens DW, de Bruin TW. 17 beta-Estradiol improves postprandial lipid metabolism in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80(1):249–253. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.1.7829621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koutsari C, Snozek CL, Jensen MD. Plasma NEFA storage in adipose tissue in the postprandial state: sex-related and regional differences. Diabetologia. 2008;51(11):2041–2048. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-1126-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mekki N, Christofilis MA, Charbonnier M, Atlan-Gepner C, Defoort C, Juhel C, et al. Influence of obesity and body fat distribution on postprandial lipemia and triglyceride-rich lipoproteins in adult women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84(1):184–191. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.1.5397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Westerterp KR, Smeets A, Lejeune MP, Wouters-Adriaens MP, Westerterp-Plantenga MS. Dietary fat oxidation as a function of body fat. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(1):132–135. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.1.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Pelt RE, Evans EM, Schechtman KB, Ehsani AA, Kohrt WM. Contributions of total and regional fat mass to risk for cardiovascular disease in older women. Am J Physiol: Endocrin Metab. 2002;282(5):E1023–E1028. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00467.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Pelt RE, Jankowski CM, Gozansky WS, Schwartz RS, Kohrt WM. Lower-body adiposity and metabolic protection in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(8):4573–4578. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jensen MD. Gender differences in regional fatty acid metabolism before and after meal ingestion. J Clin Invest. 1995;96(5):2297–2303. doi: 10.1172/JCI118285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dipietro L, Caspersen CJ, Ostfeld AM, Nadel ER. A survey for assessing physical activity among older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1993;25(5):628–642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cunningham JJ. Body composition as a determinant of energy expenditure: a synthetic review and a proposed general prediction equation. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;54(6):963–969. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/54.6.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Pelt RE, Jones PP, Davy KP, Desouza CA, Tanaka H, Davy BM, et al. Regular exercise and the age-related decline in resting metabolic rate in women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82(10):3208–3212. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.10.4268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frayn KN. Calculation of substrate oxidation rates in vivo from gaseous exchange. J Appl Physiol. 1983;55(2):628–634. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1983.55.2.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Traber MG, Kayden HJ, Rindler MJ. Polarized secretion of newly synthesized lipoproteins by the Caco-2 human intestinal cell line. J Lipid Res. 1987;28(11):1350–1363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coleman SR. Structural fat grafts: the ideal filler? Clinics in Plastic Surgery. 2001;28(1):111–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jensen MD, Sarr MG, Dumesic DA, Southorn PA, Levine JA. Regional uptake of meal fatty acids in humans. Am J Physiol: Endocrin Metab. 2003;285(6):E1282–E1288. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00220.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DiGirolamo M, Mendlinger S, Fertig JW. A simple method to determine fat cell size and number in four mamalian species. Am J Physiol. 1971;221(3):850–858. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1971.221.3.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackman MR, Steig A, Higgins JA, Johnson GC, Fleming-Elder BK, Bessesen DH, et al. Weight regain after sustained weight reduction is accompanied by suppressed oxidation of dietary fat and adipocyte hyperplasia. Am J Physiol: Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;294(4):R1117–R1129. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00808.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sadur CN, Eckel RH. Insulin stimulation of adipose tissue lipoprotein lipase. Use of the euglycemic clamp technique. J Clin Invest. 1982;69(5):1119–1125. doi: 10.1172/JCI110547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dole VP. Relation between non-esterified fatty acids in plasma and metabolism of glucose. J Clin Invest. 1956;35:150–154. doi: 10.1172/JCI103259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Björntorp P, Bertchtold P, Holm J, Larsson B. The glucose uptake of human adipose tissue in obesity. Eur J Clin Invest. 1971;1(480):485. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1971.tb00559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Romanski SA, Nelson RM, Jensen MD. Meal fatty acid uptake in adipose tissue: gender effects in nonobese humans. Am J Physiol: Endocrin Metab. 2000;279(2):E455–E462. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2000.279.2.E455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hokanson JE, Austin MA. Plasma triglyceride level is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease independent of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level: a meta-analysis of population-based prospective studies. J Cardiovasc Risk. 1996;3(2):213–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patsch JR, Miesenböck G, Hopferwieser T, Muhlberger V, Knapp E, Dunn JK, et al. Relation of triglyceride metabolism and coronary artery disease. Studies in the postprandial state. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1992;12(11):1336–1345. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.12.11.1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Santosa S, Jensen MD. Adipocyte fatty acid storage factors enhance subcutaneous fat storage in postmenopausal women. Diabetes. 2013;62(3):775–782. doi: 10.2337/db12-0912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fried SK, Kral JG. Sex differences in regional distribution of fat cell size and lipoprotein lipase activity in morbidly obese patients. Int J Obes. 1987;11(2):129–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Votruba SB, Jensen MD. Sex differences in abdominal, gluteal, and thigh LPL activity. Am J Physiol: Endocrin Metab. 2007;292(6):E1823–E1828. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00601.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tchoukalova YD, Votruba SB, Tchkonia T, Giorgadze N, Kirkland JL, Jensen MD. Regional differences in cellular mechanisms of adipose tissue gain with overfeeding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(42):18226–18231. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005259107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rebuffe-Scrive M, Eldh J, Hafstrom LO, Björntorp P. Metabolism of mammary, abdominal, and femoral adipocytes in women before and after menopause. Metabolism. 1986;35(9):792–797. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(86)90217-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lindberg UB, Crona N, Silfverstolpe G, Björntorp P, Rebuffe-Scrive M. Regional adipose tissue metabolism in postmenopausal women after treatment with exogenous sex steroids. Horm Metab Res. 1990;22(6):345–351. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1004917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marin P, Oden B, Björntorp P. Assimilation and mobilization of triglycerides in subcutaneous abdominal and femoral adipose tissue in vivo in men: Effects of androgens. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80:239–243. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.1.7829619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marin P, Rebuff-Scrive M, Björntorp P. Uptake of triglyceride fatty acids in adipose tissue in vivo in man. Eur J Clin Invest. 1990;20:158–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1990.tb02263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]