Abstract

Background

Among youth in substance use treatment, peer substance use consistently predicts worse treatment outcome. This study characterized personal (ego-centric) networks of treated youth, and examined predictors of adolescents’ motivation and perceived difficulty in making changes in the peer network to support recovery.

Methods

Adolescents (ages 14–18, n=155) recruited from substance use treatment reported on substance use severity, motivation to abstain from substance use, abstinence goals such as “temporary abstinence”, motivation and perceived difficulty in reducing contact with substance using peers, and personal network characteristics. Personal network variables included composition (proportion of abstinent peers); and structure (number of network members, extent of ties among members) for household and non-household (peer) members.

Results

Although a majority of peer network members were perceived as using alcohol or marijuana, youth in treatment had relatively high motivation to abstain from substance use. However, treated youths’ motivation to reduce contact with substance using peers was relatively low. In particular, a goal of temporary abstinence was associated with lower motivation to change the peer network. For marijuana, specifically, network composition features (proportion of abstinent peers) were associated with motivation and perceived difficulty to change the peer network. For marijuana, in particular, network structural variables (extent of ties among members) were associated only with perceived difficulty of changing the peer network.

Conclusions

Despite high motivation to abstain from substance use during treatment, adolescents reported low motivation to reduce contact with substance using peers. Personal motivation to abstain and abstinence goal predicted motivation to reduce contact with substance using peers. In contrast, particularly for marijuana, network structure predicted perceived difficulty of network change. Results highlight the potential utility of addressing motivation and perceived difficulty to change the peer network as part of youth network-based interventions.

Keywords: adolescent, social network, substance use treatment, alcohol, marijuana

INTRODUCTION

In a social-ecological framework, social groups such as family and friends provide “norms”, that is, shared values, attitudes, behaviors, as well as opportunities, such as availability and access to substances, that foster or constrain certain behaviors1, 2. Among youth in substance use treatment, substance use with peers is a commonly reported context for relapse episodes3, and peer substance use consistently predicts worse treatment outcome4, 5. Few studies, however, have characterized the social networks of adolescents in substance use treatment, and in particular, treated adolescents’ motivation for and perceived difficulty of reducing contact with substance using peers, who could play a role in relapse episodes. Increased understanding of personal network characteristics and motivation to reduce contact with substance using peers among youth in treatment has implications for understanding barriers to positive behavior change, and refining network-based interventions to reduce substance use.

Most social network studies in the field of addictions treatment have focused on personal network composition, that is, the characteristics of network members, such as proportion of abstinent or substance using members, number of males, as reported by the respondent. Personal network studies consistently report a positive association between perceived substance use among network members and an individual’s own substance use severity6, 7, as well as a positive association between proportion of abstinent or abstinence supportive network members and an individual’s ability to maintain abstinence8. Specifically, among youth in brief substance abuse treatment, adolescents reported that a majority of close friends were substance users and very few close friends abstained from substance use at the start of treatment9. To date, personal network studies conducted with treated youth have focused on peers9, although parental and sibling substance use (household member characteristics), have been associated with youth treatment outcomes4, 5.

Personal network studies also have examined network structure in relation to substance use severity. Network structural features include “nodes,” which are used to represent network members and ties between nodes, whereas network composition refers to node characteristics, such as the number or proportion of female members. The most common structural network features that have been examined include the total number of members (“degree”), and the extent of ties between members (“density”). Network structural characteristics, particularly density, can provide information on the extent to which network members may collectively foster or constrain an individual’s attitudes and behaviors10. For example, a network with high density or many ties among substance using members could foster an adolescent’s substance use through norms that support use and opportunities to use. Some studies of network structure have found a positive association between network density and youth substance use11, whereas other studies have found no association between network density and substance use7. In sum, while mixed findings have been reported for network structure, such as density, as a correlate of substance use severity, network composition has been more consistently related to severity of substance involvement. No studies have examined both network structure and composition in relation to treated adolescents’ severity of substance use.

Despite recognition of the role that substance using peers can play in a treated adolescent’s risk for relapse3, 12, little is known about treated youths’ motivation to reduce contact with substance using peers, and perceived difficulty of shifting the personal network to reduce affiliation with substance using peers. Motivation and perceived difficulty to reduce contact with substance using peers might be associated with features of network composition, such as proportion of abstinent peers; and structure, such as degree and density. For example, network structural characteristics such as density (the extent of ties among members) might predict “perceived difficulty” of changing the network. That is, the extent of ties among members may make it difficult to selectively retain, exclude, or have limited contact with certain members10. Greater understanding of the extent to which personal network composition and structure are associated with motivation and perceived difficulty of shifting the peer network could reveal targets for network-based intervention.

Other factors that might be associated with motivation for and perceived difficulty of reducing contact with substance using peers include a person’s own motivation and commitment to specific goals for reducing substance use. Motivation and goal commitment both play important roles in theories of behavior change13. For example, an adolescent’s high motivation to abstain from a substance might be positively associated with motivation to reduce contact with substance using peers. Further, regarding specific personal goals for abstinence, a goal of temporary abstinence13, might be associated with low motivation to reduce contact with substance using peers, given the time-limited nature of the personal abstinence goal. Little is known regarding the extent to which features of network composition and structure are associated with motivation and perceived difficulty of reducing contact with substance using peers, over and above factors such as personal motivation to abstain and specific goals regarding substance use.

This cross-sectional study aimed to characterize the personal network characteristics of youth enrolled in outpatient substance use treatment, and adolescents’ motivation for and perceived difficulty of reducing contact with substance using peers. In addition, we examined personal network composition and structure as predictors of (1) alcohol and marijuana problem severity, (2) motivation for, and (3) perceived difficulty of reducing contact with substance using peers. We hypothesized that a higher proportion of abstinent peers (network composition) would be associated with lower substance use severity. We further predicted that a greater proportion of abstinent members (network composition) would predict greater motivation to change the peer network, whereas network structural features, such as density of ties among peers, would predict perceived difficulty of reducing contact with substance using peers. We explored the extent to which network characteristics would predict motivation for and perceived difficulty of reducing contact with substance using peers over and above personal motivation to abstain and abstinence goal.

METHODS

Participants

Among 262 youth ages 14–18 in community-based intensive outpatient treatment (IOP) for substance use, who expressed interest in participating in a longitudinal research study, 59% (n=155) completed a baseline assessment. Table 1 presents sample descriptive statistics. It was not possible to compare youth who did versus did not participate. However, sample demographic and substance use characteristics are generally similar to those of youth admitted to publicly funded substance use treatment14, and to other studies15, 16.

TABLE 1.

Sample (N=155) descriptive statistics

| n | % or Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Male | 116 | 74.8 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White | 129 | 83.2 |

| Black | 13 | 8.4 |

| Multi-racial | 13 | 8.4 |

| Age | 155 | 16.9 (1.1) |

| Socio-economic status (1=high, 5=low) | 155 | 2.5 (1.1) |

| Past Year DSM-IV diagnosis | ||

| Alcohol use disorder | 50 | 32.3 |

| Alcohol abuse | 46 | 29.7 |

| Alcohol dependence | 4 | 2.6 |

| Marijuana use disorder | 143 | 92.2 |

| Marijuana abuse | 116 | 74.8 |

| Marijuana dependence | 27 | 17.4 |

| Conduct disorder | 37 | 23.9 |

| Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder | 35 | 22.6 |

| Oppositional defiant disorder | 28 | 18.1 |

| Major depressive disorder | 13 | 8.4 |

| DSM-IV Alcohol symptom count | 155 | 1.1 (1.5) |

| DSM-IV Marijuana symptom count | 155 | 3.7 (2.1) |

Procedure

Youth admitted to a community-based IOP substance use treatment program that operated six regional sites were approached to participate in a longitudinal study on treatment outcome. All sites were part of the same overall treatment program, such that treatment format and content were similar across all sites. IOP consisted of three 3-hour group sessions per week for 6–8 weeks, with content such as relapse prevention and 12-step facilitation, which supported a goal of abstinence from alcohol and illicit drugs. Informed consent or assent was obtained prior to study participation. The baseline assessment was typically completed within two weeks of starting IOP. Youth were compensated for study participation. The university’s Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol.

Measures

An adapted Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV SUDs (SCID)17 was used to determine current (past year) SUD diagnoses and symptom counts, that is, the total number of DSM-IV abuse and dependence symptoms, for alcohol (11 symptoms) and marijuana (10 symptoms). The Kiddie-Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia18 was used to assess current DSM-IV psychopathology.

Motivation to Abstain for alcohol and marijuana was assessed with the item “How motivated are you to abstain from [substance] in the next 30 days?” rated on a 10-point scale (1=not motivated to 10=very motivated). Difficulty to Abstain from alcohol and marijuana was assessed with the item “How difficult will it be for you to abstain from marijuana for the next 30 days?” rated on a 10-point scale (1=not difficult to 10=very difficult). The Thoughts About Abstinence measure13 asked respondents to select one of six goals (rated separately for alcohol and marijuana): 1=total abstinence, never use again; 2=total abstinence, but realize a slip is possible; 3=occasional use when urges strongly felt; 4=temporary abstinence; 5=controlled use; 6=no goal. These single item measures have demonstrated good concurrent and predictive validity19, 20.

Motivation and difficulty to reduce contact with alcohol and marijuana using peers were assessed with the items “Thinking about your close friends, in the next 30 days, how motivated are you to reduce (or have minimal) contact with friends who use [substance]?” and “Thinking about your close friends, in the next 30 days, how difficult would or will it be to reduce (or have minimal) contact with friends who use [substance]?” Items were rated on a 10-point scale (1=not at all to 10=very). These items were constructed to parallel items assessing motivation and perceived difficulty to abstain from alcohol and marijuana use, which have good concurrent and predictive validity20.

Egocentric network data were collected using a structured interview format10, 21 in which the adolescent (“ego”) named a minimum of 10 people (age 10 and older), who are “the most important to you, which can include a romantic partner, friends, parent, brothers, sisters, relatives like cousins, or other adults with whom you spent the most time with, felt closest to”. “Household members” were defined as individuals currently residing with “ego”. Household member information was collected for all cases except (inadvertently) the first completed case. For each network member (“alter”), participants reported: gender, duration of relationship, household membership, how close the ego felt to the alter (0=not close to 10=very close), perceived frequency of alter’s alcohol and marijuana use (number of days of use in the past month), and perception of how the alter would react to the ego’s use of alcohol or marijuana (1=discourages use to 5=encourages use). Participants also rated the perceived closeness of each pair of alters (0=not close to 10=very close). Egocentric network data collected by structured interview has demonstrated good interrater and test-retest reliability22, 23.

Data analysis

SPSS version 2124 was used to perform the descriptive and multivariate regression analyses. Descriptive statistics were computed separately for household and non-household subgroups. E-Net25, 26 software was used to compute network composition and structure measures. E-Net performs computations on raw network data, for example, the characteristics of each member and strength of ties between members, to generate network measures such as degree (number of network members reported) and density (the sum of all tie strengths divided by all possible ties). Regarding network density, higher values indicate greater density. The observed range for network density in the sample was 0–5. E-Net also can be used to visualize and graph individual networks.

Three sets of multivariate regression analyses (simultaneous entry of variables) were conducted to examine personal network composition and structure as predictors of alcohol and marijuana problem severity prior to treatment, motivation for reducing contact with substance using peers, and perceived difficulty of reducing contact with substance using peers, controlling for relevant covariates. Variables were screened for non-normality; results did not differ using transformed variables, so untransformed results are reported.

RESULTS

As seen in Table 2, youth, on average, had relatively high motivation to abstain from alcohol (mean=7.8 on a 10-point scale, SD=3.1) and marijuana (mean=8.6, SD=2.3). Almost one-quarter of adolescents (24%) had a “temporary” abstinence goal for alcohol, and the same proportion (24%) reported this goal for marijuana; 8% reported a temporary abstinence goal for both alcohol and marijuana (see Table 2). For the “temporary abstinence” variable used in the regression analyses below, “temporary abstinence” was coded “1” and all other responses to the Thoughts About Abstinence measure were coded “0”. This coding scheme was based on preliminary analyses, which indicated that the other goals coded in the Thoughts About Abstinence measure generally showed a linear association with motivation to abstain, with the exception of “temporary abstinence”.

TABLE 2.

Descriptive statistics for Motivation and Difficulty to Abstain, Thoughts About Abstinence, and Personal Network Characteristics

| Substance | Alcohol | Marijuana | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motivation and Difficulty to Abstain | n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) |

| Motivation to abstain from use | 146 | 7.8 (3.1) | 152 | 8.6 (2.3) |

| Difficulty in abstaining from use | 146 | 2.8 (2.6) | 152 | 4.3 (3.3) |

| Motivation to reduce contact with using peers | 152 | 4.1 (3.2) | 152 | 4.5 (3.4) |

| Difficulty in reducing contact with using peers | 152 | 5.4 (3.4) | 152 | 6.2 (3.4) |

| Thoughts About Abstinencea,b | n | % | n | % |

| Total abstinence | 31 | 20.9 | 35 | 23.0 |

| Slip is possible | 24 | 16.2 | 44 | 28.9 |

| Occasional use | 20 | 13.5 | 16 | 10.5 |

| Temporary Abstinence | 35 | 23.6 | 37 | 24.3 |

| Controlled Use | 18 | 12.2 | 13 | 8.6 |

| No goal | 20 | 13.5 | 7 | 4.6 |

| Network description | Household | Non-Household | ||

| Structural features | n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) |

| Total number of members (Degree) | 154 | 2.5 (1.0) | 155 | 8.1 (2.0) |

| Density | 154 | 4.0 (1.3) | 155 | 2.2 (1.0) |

| Composition features | n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) |

| Percent abstinent from alcohol (past month) | 154 | 54.8 (38.3) | 155 | 41.2 (29.9) |

| Percent abstinent from marijuana (past month) | 154 | 90.5 (21.3) | 155 | 41.3 (27.0) |

| Reaction to adolescent’s drinking | 154 | 1.3 (0.6) | 155 | 2.5 (0.9) |

Note.

= Alcohol thoughts about abstinence “Not applicable” is coded as missing, n=7.

= Marijuana thoughts about abstinence “Not applicable” is coded as missing, n=3.

Table 2 also indicates that the average number of household members was 2.5 (SD=1.0), and the average number of non-household (peer) members was 8.1 (SD=2.0). Average ratings of how close ego felt to an alter were relatively high for listed household members (mean= 7.6, SD=2.1) and non-household (peer) members (mean=7.6, SD=1.4), which is consistent with instructions to name “close” friends. Relationship duration for all household members was >6 months. For non-household members (peers), 81.3% of youth reported that peer relations were ≥6 months in duration. Peer relationship data suggest that most, if not all, non-household members (peers) were known prior to treatment entry.

As presented in Table 2, a majority of household members was reported to be abstinent from alcohol (55%) and marijuana (90%) in the past month, whereas a minority of non-household (peer) members was perceived to be abstinent from alcohol (41%) and marijuana (41%).

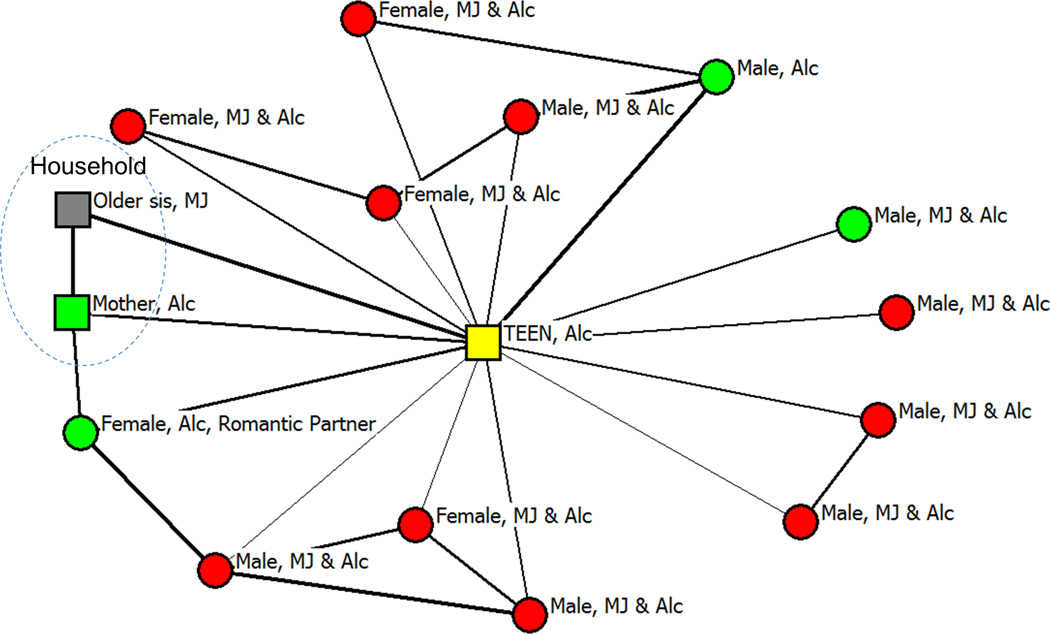

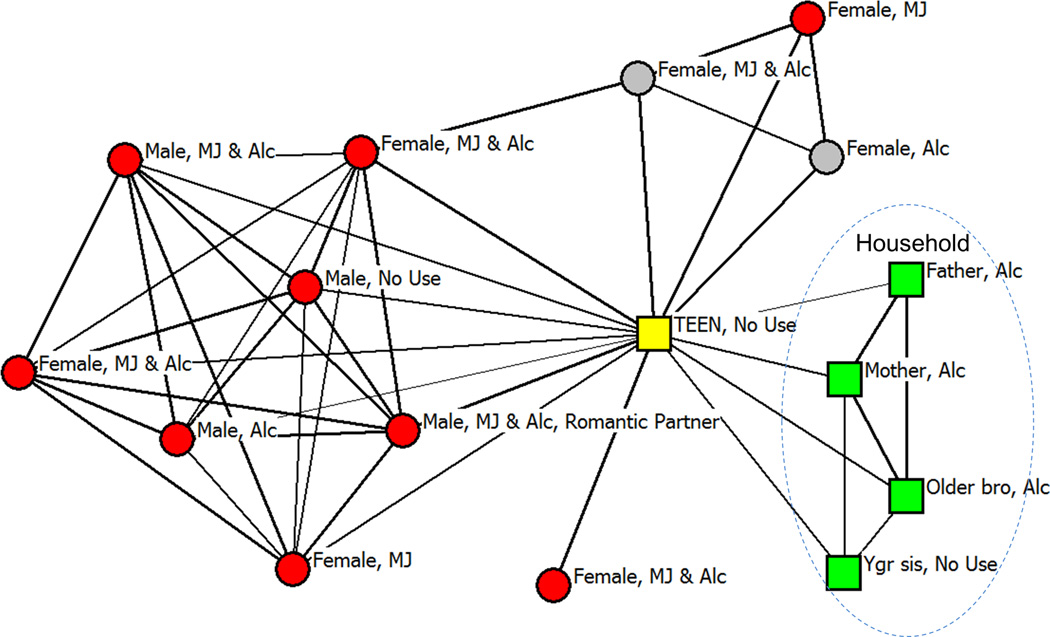

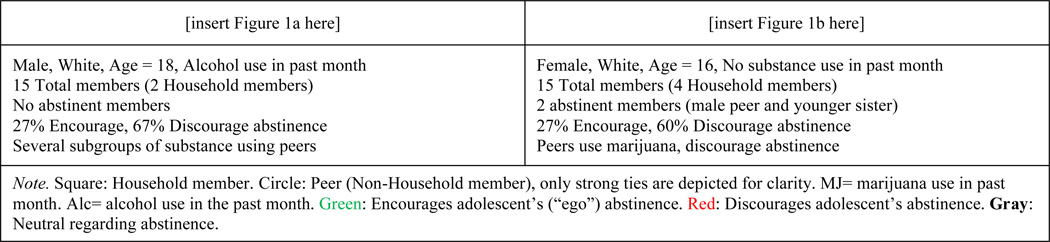

Two example networks are depicted in the Figure. These networks could be considered “risky” in that few members are abstinent, and most members are perceived as discouraging abstinence.

Figure 1.

Personal (Ego) Network Examples

The first set of regression analyses examined network characteristics as predictors of substance use severity (Table 3). For alcohol, results indicated that two network structural characteristics, greater number of household members (β= −.41) and greater density of ties among household members (β= −.55), as well as a feature of network composition, greater percentage of alcohol abstinent peers, were each uniquely associated with lower alcohol problem severity. For marijuana, younger age (β= .22) and greater percentage of marijuana abstinent peers (β= −.16), were each independently associated with lower marijuana problem severity. In sum, as hypothesized, the proportion of abstinent peers (network composition) was inversely associated with problem severity for both alcohol and marijuana. Network structure (household degree and density), however, was only associated with alcohol, and not marijuana, problem severity.

TABLE 3.

Regression Models Predicting DSM-IV Alcohol And Marijuana Symptom Count (Simultaneous Entry Of All Variables)

| ALCOHOL | Standardized Beta |

t |

|---|---|---|

| Age | .09 | 1.15 |

| Sex | −.08 | −.99 |

| Race | .09 | 1.24 |

| Household members: Degree (Network structure) | −.41 | −3.41*** |

| Household members: Density (Network structure) | −.55 | −4.32*** |

| Non-Household members: Degree (Network structure) | .08 | .96 |

| Non-Household members: Density (Network structure) | .06 | .75 |

| Household: percent alcohol abstinent in past month (Network composition) | .15 | 1.77 |

| Peers: percent alcohol abstinent in past month (Network composition) | −.32 | −3.80*** |

| Model summary: R2=0.22, F(9, 143)=4.56, p<.001 | ||

| MARIJUANA | Standardized Beta |

t |

| Age | .22 | 2.58* |

| Sex | .08 | 1.05 |

| Race | .09 | 1.07 |

| Household members: Degree (Network structure) | −.14 | −1.11 |

| Household members: Density (Network structure) | −.14 | −1.00 |

| Non-Household members: Degree (Network structure) | .14 | 1.72 |

| Non-Household members: Density (Network structure) | −.04 | −.46 |

| Household: percent marijuana abstinent in past month (Network composition) | .01 | .15 |

| Peers: percent marijuana abstinent in past month (Network composition) | −.16 | −2.04* |

| Model summary: R2=0.12, F(9, 144)=2.16, p=.03 | ||

Note. Sex coded as: 0=Female, 1=Male; Race coded as: 0=Minority race/ethnicity, 1=White. Treatment sites did not differ on demographic characteristics, substance use severity, or motivation/difficulty variables (ps>.07), therefore site was not a covariate.

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001

The second set of analyses aimed to identify predictors of motivation to reduce contact with substance using peers (Table 4). Network structure variables were not included because preliminary analyses indicated that these variables were not associated with motivation for network change (p>.05). For alcohol, younger age (β= .16), lower motivation to abstain (β= .45), and a temporary goal of abstinence from alcohol (β= −.17) were each associated with lower motivation to reduce contact with alcohol using peers. For marijuana, lower marijuana symptom count (β= .21), lower motivation to abstain (β= .17), a temporary goal of abstinence from marijuana (β= −.23), and lower proportion of marijuana abstinent peers (β= .23) were each associated with lower motivation to reduce contact with marijuana using peers. For both alcohol and marijuana, a temporary abstinence goal and lower motivation to abstain from the substance uniquely predicted lower motivation to reduce contact with substance using peers. Contrary to prediction, greater proportion of abstinent members (network composition) was only uniquely associated with motivation to reduce contact with marijuana, but not alcohol, using peers.

TABLE 4.

Regression Models Predicting “Motivation To Reduce Contact” With Substance Using Peers In The Social Network (Simultaneous Entry Of All Variables)

| ALCOHOL | Standardized Beta |

t |

|---|---|---|

| Age | .16 | 2.01* |

| Sex | −.04 | −.55 |

| Race | .00 | −.01 |

| Alcohol symptom count | .09 | 1.06 |

| Motivation to abstain from alcohol | .45 | 4.66*** |

| Difficulty to abstain from alcohol | −.09 | −1.04 |

| Temporary abstinence | −.17 | −2.11* |

| Peer reaction to alcohol use (Network composition) | −.08 | −.83 |

| Peers: percent alcohol abstinent in past month (Network composition) | .06 | .58 |

| Household reaction to alcohol use (Network composition) | .04 | .43 |

| Household: percent alcohol abstinent in past month (Network composition) | −.10 | −1.26 |

| Model summary: R2=0.27, F(11, 132)=4.37, p<.001 | ||

| MARIJUANA | Standardized Beta |

t |

| Age | .10 | 1.30 |

| Sex | −.09 | −1.16 |

| Race | −.02 | −.19 |

| Marijuana symptom count | .21 | 2.67** |

| Motivation to abstain from marijuana | .17 | 2.05* |

| Difficulty to abstain from marijuana | −.08 | −.90 |

| Temporary abstinence | −.23 | −3.02** |

| Peer reaction to marijuana use (Network composition) | −.09 | −.99 |

| Peers: percent marijuana abstinent in past month (Network composition) | .23 | 2.72** |

| Household reaction to marijuana use (Network composition) | .01 | .09 |

| Household: percent marijuana abstinent in past month (Network composition) | −.06 | −.80 |

| Model summary: R2=0.26, F(11, 138)=4.37, p<.001 | ||

Note. Temporary abstinence (coded 1= temporary abstinence goal, 0= all other goals); a negative association indicates that temporary abstinence was associated with lower motivation to reduce contact. Motivation to abstain (coded 1=low through 10=high); a positive association indicates that greater motivation to abstain was associated with greater motivation to reduce contact with substance using peers. Peer reaction to alcohol use= average rating across non-household peers; Household reaction to alcohol use= average rating across household members. Treatment sites did not differ on demographic characteristics, substance use severity, or motivation/difficulty variables (ps>.07), therefore site was not a covariate.

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001

The third set of analyses examined network characteristics as predictors of perceived difficulty in reducing contact with substance using peers (Table 5). Temporary abstinence was not included in the model because it was not associated with “difficulty” in reducing contact with peers (p>.05). For alcohol, lower number of non-household peers (β= .23), lower density of ties among non-household peers (β= .18), and greater motivation to abstain (β= −.26) were independently associated with lower perceived difficulty in reducing contact with alcohol using peers. For marijuana, lower number of non-household peers (β= .24), lower density of ties among non-household peers (β= .19), as well as lower proportion of marijuana abstinent peers in the network (β= −.24), and less perceived difficulty in abstaining from marijuana (β= .21) were uniquely associated with lower perceived difficulty in reducing contact with marijuana using peers. For both alcohol and marijuana, consistent with prediction, non-household (peer) structural characteristics (degree and density), were positively associated with perceived difficulty in reducing contact with substance using peers.

TABLE 5.

Regression Models Predicting “Difficulty In Reducing Contact” With Substance Using Peers In The Social Network (Simultaneous Entry Of All Variables)

| ALCOHOL | Standardized Beta |

t |

|---|---|---|

| Age | .00 | −.03 |

| Sex | −.12 | −1.47 |

| Race | .03 | .34 |

| Alcohol symptom count | .08 | .97 |

| Motivation to abstain from alcohol | −.26 | −2.89** |

| Difficulty to abstain from alcohol | −.04 | −.50 |

| Peer network: degree (Network structure) | .23 | 3.04** |

| Peer network: density (Network structure) | .18 | 2.24* |

| Peer reaction to alcohol use (Network composition) | .06 | .65 |

| Peers: percent alcohol abstinent in past month (Network composition) | −.17 | −1.89 |

| Model summary: R2=0.26, F(10, 134)=4.66, p<.001 | ||

| MARIJUANA | Standardized Beta |

t |

| Age | −.09 | −1.17 |

| Sex | −.12 | −1.59 |

| Race | .09 | 1.26 |

| Marijuana symptom count | .06 | .75 |

| Motivation to abstain from marijuana | −.01 | −.08 |

| Difficulty to abstain from marijuana | .21 | 2.51* |

| Peer network: degree (Network structure) | .24 | 3.28** |

| Peer network: density (Network structure) | .19 | 2.50* |

| Peer reaction to marijuana use (Network composition) | .10 | 1.23 |

| Peers: percent marijuana abstinent in past month (Network composition) | −.24 | −2.85** |

| Model summary: R2=0.28, F(10, 140)=5.33, p<.001 | ||

Note. Peer reaction to alcohol use= average rating across non-household members. Treatment sites did not differ on demographic characteristics, substance use severity, or motivation/difficulty variables (ps>.07), therefore site was not a covariate.

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001

DISCUSSION

In this outpatient sample, adolescents reported, on average, high motivation to abstain from alcohol and marijuana, but low motivation to reduce contact with substance using peers. Although greater proportion of abstinent peers was inversely associated with severity of alcohol and marijuana use, contrary to expectation, network composition (proportion of abstinent members) was only a unique predictor of motivation for network change for marijuana, and not also for alcohol use. For both alcohol and marijuana, lower personal motivation to abstain and temporary abstinence goal independently predicted lower motivation for network change. With regard to perceived difficulty of network change, as hypothesized, peer network structure (degree, density) was uniquely associated with perceived difficulty of reducing contact with substance using peers. Results highlight the role of network structural characteristics, such as density, in perceived difficulty of network change, and of personal motivation and goals in relation to motivation for network change.

Consistent with a social ecological model and prior research9, results indicated that a greater proportion of abstinent peers was associated with lower alcohol and marijuana problem severity. This study extends prior research by examining both household and peer network members, an approach indicating that abstinence among household members was not uniquely associated with youth substance use severity when considered in the context of abstinence among network peers. Although research indicates important effects of parental and sibling substance involvement on treated teens’ substance use4, the current study’s results suggest the importance of peer, relative to household, network composition as a correlate of youth substance use severity.

With regard to network structural characteristics, more household members and stronger ties among household members were each uniquely associated with lower alcohol, but not marijuana, problem severity. The specificity of network structural features in relation to specific outcomes (by member subgroup: household vs. peer, type of substance) points to the complexity of interpreting how network structural features might constrain or contribute to certain health behaviors10, 27. This specificity of network structure in relation to substance use severity, in addition to sample-specific characteristics, could help to explain why, in prior research, one study found a positive association between network density and youth substance use11, whereas another found no association7. More generally, aspects of network structure, such as density, appear to be less robustly associated with substance use severity relative to features of network composition.

In predicting motivation to reduce contact with substance using peers, results indicate coherent associations among personal motivation to abstain, temporary abstinence goals, and motivation to reduce contact with substance using peers. Specifically, although an adolescent might be highly motivated to abstain from substance use while in treatment, a temporary abstinence goal, in particular, could set limits on the extent of lifestyle or social environmental (peer network) changes that the adolescent is willing to make. For youth who endorse a temporary abstinence goal, motivational interventions provided during treatment and after treatment, for example, through booster sessions or in continuing care, could help to extend recovery goals over time.

As expected, network structure (degree, density) was associated with perceived difficulty of reducing contact with substance using peers, a novel finding that emphasizes how features of peer network structure might contribute to challenges in modifying the peer network to support recovery. Specifically, dense ties among peers may make it difficult to selectively reduce contact with or exclude certain members, while still retaining others. A qualitative study of treated youth indicated that discussion of peer relationships during treatment (cf.12) helped youth to recognize positive and negative peers in the network9. Current results suggest the potential utility of also discussing aspects of network structure, such as closeness among peers, which may impact perceived difficulty of network change, and possibilities for shifting the personal network to support recovery.

Study limitations warrant comment. The generalizability of results is limited to youth in substance use treatment, most of whom were White males receiving treatment for marijuana use. Personal network data collection is based on the respondent’s perception of network member behavior and attitudes, and could reflect a false consensus effect28. Self-reported substance use may be subject to bias, although conditions such as using a saliva drug screen, which facilitate valid reporting, were used. The cross-sectional data do not provide information on temporal ordering to examine peer selection versus peer influence.

This study found that youth in treatment were generally motivated to abstain from alcohol and marijuana use, but reported lower motivation to reduce contact with substance using peers. Personal motivation and goals for abstinence were important predictors of motivation to reduce contact with substance using peers, whereas network structure was an important predictor of perceived difficulty of network change. Study findings suggest that personal network interventions could address adolescents’ motivation and perceived difficulty to change the peer network when discussing personal network composition and structure, in order to facilitate positive network change and improve youth treatment outcomes.

ACKNOWLEGEMENTS

We thank Allan Clifton for his consultation on the project. Portions of this work were presented as a poster at the 2012 Research Society on Alcoholism meeting.

FUNDING

This work was supported by NIAAA R01 AA014357, K02 AA018195, 2K05 AA16928. The funding agency was not involved in the work reported, or in the composition of the manuscript.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr. Chung was responsible for study design and data analysis. Ms. Abraham, Ms. Ruglovsky, Ms. Schall were involved in data collection. Dr. Chung, Ms. Sealy, Ms. Abraham, Ms. Ruglovsky, Ms. Schall, and Dr. Maisto were involved in interpretation of results and the writing and revision of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valente TW, Gallaher P, Mouttapa M. Using social networks to understand and prevent substance use: A transdiciplinary perpsective. Subst Use Misuse. 2004;39:1685–1712. doi: 10.1081/ja-200033210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown S. Measuring youth outcomes from alcohol and drug treatment. Addiction. 2004;99(supp 2):38–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams RJ, Chang SY Addiction Centre Research Group. A comprehensive and comparative review of adolescent substance abuse treatment outcome. Clin Psychol-Sci Pr. 2000;7:136–166. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chung T, Maisto SA. Relapse to alcohol and other drug use in treated adolescents: review and reconsideration of relapse as a change point in clinical course. Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26:149–161. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zywiak WH, Neighbors CJ, Martin RA, Johnson JE, Eaton CA, Rohsenow DJ. The Important People Drug and Alcohol interview: psychometric properties, predictive validity, and implications for treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009;36:321–330. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wenzel SL, Tucker JS, Golinelli D, Green HD, Jr, Zhou A. Personal network correlates of alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use among homeless youth. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;112:140–149. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bond J, Kaskutas LA, Weisner C. The persistent influence of social networks and alcoholics anonymous on abstinence. J Stud Alcohol. 2003;64:579–588. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mason M. Social network characteristics of urban adolescents in brief substance abuse treatment. J Child Adolesc Substance Abuse. 2009;18:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCarty C. Structure in personal networks. J Social Structure. 2002;3 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rice E, Milburn NG, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Mallett S, Rosenthal D. The Effects of Peer Group Network Properties on Drug Use Among Homeless Youth. Am Behav Sci. 2005;48:1102–1123. doi: 10.1177/0002764204274194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sampl S, Kadden R. Motivational enhancement therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy for adolescent cannabis users: 5 sessions, Cannabis Youth Treatment series, volume 1. Rockville, MD: Center for Substance Abuse treatment, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall SM, Havassy BE, Wasserman D. Commitment to abstinence and acute stress in relapse to alcohol, opiates, and nicotine. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1990;58:175–181. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.2.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS) 1999–2009: National Admissions to Substance Abuse Treatment Services. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2011. Vol DASIS Series: S-56 (SMA) 11-4646. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chi FW, Kaskutas LA, Sterling S, Campbell CI, Weisner C. Twelve-Step affiliation and 3-year substance use outcomes among adolescents: social support and religious service attendance as potential mediators. Addiction. 2009;104:927–939. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02524.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelly JF, Urbanoski K. Youth recovery contexts: the incremental effects of 12-step attendance and involvement on adolescent outpatient outcomes. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36:1219–1229. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01727.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders. New York, NY: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, et al. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Psy. 1997;36:980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amodei N, Lamb RJ. Convergent and concurrent validity of the Contemplation Ladder and URICA scales. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;73:301–306. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.King KM, Chung T, Maisto SA. Adolescents' thoughts about abstinence curb the return of marijuana use during and after treatment. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77:554–565. doi: 10.1037/a0015391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCarty C, Killworth PD, Rennell J. Impact of methods for reducing respondent burden on personal network structural measures. Soc Networks. 2007;29:300–315. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tracy EM, Catalano RF, Whittaker JK, Fine D. Reliability and social network data (Research note) Soc Work Res Abstr. 1990;26:33–35. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clair S, Schensul J, Raju M, Stanek E, Pino R. Will you remember in the morning? Test-retest reliability of a social network analysis examining HIV-related risky behavior in urban adolescents and young adults. Connections. 2003;25:88–97. [Google Scholar]

- 24.IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.; Released 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borgatti SP. Lexington, KY: Analytic Technologies; 2006. E-Network Software for Ego-Network Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Halgin D, Borgatti SP. An Introduction to Personal Network Analysis and Tie Churn Statistics using E-NET. Connections. 2012;32:36–48. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burt R. Structural holes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ross L, Greene D, House P. The 'False Consensus Effect': an egocentric bias in social perception and attribution processes. J Exp Soc Psychol. 1977;13:279–301. [Google Scholar]