Abstract

We examined reciprocal associations between parent-adolescent conflict and academic achievement over a two-year period. Participants were mothers, fathers, and adolescents from predominantly White, working and middle class families (N = 168). After accounting for previous academic achievement, parent-adolescent conflict predicted relative declines in academic achievement two years later. After controlling for relationship quality at Time 1, lower math grades predicted relative increases in parent-adolescent conflict two years later among families with less education.

Keywords: Parent-adolescent conflict, academic achievement, adolescence, longitudinal

Numerous studies have documented ways in which parent-adolescent relationships may influence adolescents' academic achievement (Dubois, Eitel, & Felner, 1994; Paulson, 1994; Steinberg, Lamborn, Dornbusch, & Darling, 1992; Wentzel, 1994), but much less is known about how adolescent achievement contributes to parent-adolescent relationship quality. Academic achievement can be a source of tension in families because conflict may arise when youth are not performing as well in school as their parents would like. In a review of research on adolescents' reports of the most common causes of arguments with parents, issues related to school were among the top three causes (Montemayor, 1983). In a recent study, Allison and Schultz (2004) found that issues related to school such as homework and school performance were among the most frequent and intense areas of conflict between adolescents and their parents. In the face of these findings, the question remains: Does adolescent academic performance predict subsequent parent-adolescent conflict?

The present investigation is grounded in an ecological approach to the study of adolescent development which suggests that what occurs in one setting (such as the family) has implications for what occurs in another setting (such as school), what Bronfenbrenner (1979) termed mesosystem linkages. Based upon prior work, we hypothesized that experiences in the parent-adolescent relationship such as conflict would have implications for adolescents' subsequent performance in school, but we take the novel step of examining whether adolescents' school performance also has implications for the subsequent quality of parent-adolescent relationships. Consistent with an ecological perspective, however, these associations may not operate the same way for all families. Objectively similar experiences may have different implications across different settings (Bronfenbrenner & Crouter, 1983). According to ecological theory, family processes (such as parent-adolescent conflict) and contextual factors (such as parents' educational background) often interact in affecting children's development. For example, parents may interpret and react to issues related to achievement differently depending on their own educational backgrounds. Thus in the present study we also examined whether links between parent-adolescent conflict and academic achievement differed as a function of parental education.

Parent-adolescent conflict and academic achievement are important issues during adolescence. Parent-child relationships change substantially during adolescence; changes include less time spent with parents and more conflict (Montemayor, 1982; Steinberg, 1990). Although the view of adolescence as a time of storm and stress (Hall, 1904) has been revised in recent years (Holmbeck, 1996), adolescence is a developmental period when the risk of problems in the parent-adolescent relationship increases (Rutter, Graham, Chadwick, & Yule, 1976). The adolescent years are also a crucial time for school performance. Indeed, achievement in school is one of the critical tasks defining competence during this developmental period (Masten & Coatsworth, 1998). School performance takes on new salience during the adolescent years because academic achievement is related to future opportunities in terms of higher education and employment (Henderson & Dweck, 1994). For example, adolescents' scholastic successes and failures can affect whether they are later able to attend college or qualify for certain vocational, apprenticeship, or military service training opportunities.

Parenting and Achievement

The literature on parenting styles (Baumrind, 1966; 1991) provides a solid foundation for understanding the relation between parenting and academic achievement. For example, we know that adolescents whose parents are both responsive and demanding (i.e., authoritative) have higher academic achievement than their peers (Dornbusch & Wood, 1989; Glasgow, Dornbusch, Troyer, Steinberg, & Ritter, 1997; Steinberg, Lamborn, Dornbusch, & Darling, 1992). The affective quality of parent-adolescent relationships is also an important predictor of youth's academic achievement (Crosnoe & Elder, 2004). Positive interactions between parents and adolescents are associated with higher academic achievement (Amato & Fowler, 2002). Conversely, negative or coercive family relationships convey negative messages to adolescents about themselves and their worth (Noller, 1994), which can lead adolescents to do poorly in school. Crosnoe and Elder (2004) found that emotional distance in the parent-adolescent relationship was associated with academic problems such as poor grades and school suspensions.

In a sample of young adolescents, Forehand and colleagues (1986) examined links between parent-adolescent conflict and academic achievement. Adolescents and their parents each reported on recent disagreements and the intensity of these discussions. The researchers found that as conflict intensity in the father-adolescent relationship increased, adolescent grade point average decreased. From this cross-sectional study it cannot be determined whether conflicts between fathers and adolescents are disruptive and therefore disturb adolescent school performance, or if when an adolescent's grades fall it is fathers that take the disciplinarian role thereby increasing father-adolescent conflict. Longitudinal research is needed in order to understand the nature of these unfolding linkages. Using a longitudinal cross-lagged approach, we examined whether poor school performance was related to increases in parent-adolescent conflict over time or whether more parent-adolescent conflict was related to decreases in school performance over time.

Only one longitudinal study has examined links between negative affect in parent-adolescent relationships and adolescent academic achievement (Melby & Conger, 1996). Melby and Conger (1996) asked whether negative parental affect (i.e., emotional tone), measured when students were in the 8th and 9th grades, predicted adolescent academic achievement in 10th grade. Negative parental affect was operationalized with items such as interacting with the adolescent in an angry, irritable manner and responding to misbehavior with yelling, threatening, and physical reprimands. The researchers found that adolescents had lower grades in the face of hostile parenting. Melby and Conger also found that earlier academic achievement was indirectly related to later academic achievement through its effect on hostile parenting.

In the present study, we built on the work of Melby and Conger (1996) by focusing on parent-adolescent conflict to index relationship quality. We also expanded this work to older adolescents because less is known about the nature of the association between more general parent-adolescent conflict and academic achievement in the later high school years (i.e., 11th and 12th grades), a time when issues related to academic achievement become increasing important as youth consider their post-high school plans. In the present study, we examined longitudinal associations between parent-adolescent conflict and academic achievement during the high school years. Finally, we controlled for both previous achievement and parent-adolescent conflict in order to examine cross-lagged associations. Much of the research on parent-adolescent relationships and academic achievement focuses on socialization from parents to adolescents. Although parent-adolescent relationships are widely recognized as being bi-directional in nature, researchers are rarely able to examine how adolescent characteristics, such as academic performance, contribute to parent-adolescent relationship quality.

Social Class as a Context for Parenting and Academic Achievement

A body of work links socioeconomic status (SES) to academic achievement (Duncan, Yeung, Brooks-Gunn, & Smith, 1998; Sacker, Schoon, & Bartley, 2002) and has demonstrated that lower SES is associated with lower levels of school achievement (see review by Bradley & Corwyn, 2002). Researchers have offered several reasons for this finding. First, higher-SES families have greater access to stimulating resources such as computers, museums, and books than do lower-SES families (Bradley & Corwyn, 2002). In addition, higher SES parents tend to be more involved in their children's education and to have higher expectations for their children's achievement (Sacker, Schoon, & Bartley, 2002).

Although there is no one, agreed-upon way to operationalize social class (Hughes & Perry-Jenkins, 1996), parent education is one dimension of social class that has been recognized as being particularly important in predicting children's achievement (Davis-Kean, 2005; Crosnoe, 2004; Klebanov, Brooks-Gunn, & Duncan, 1994; Schiller, Khmelkov, & Wang, 2005). In the present study, we chose parental education to index social class not only because this is a common strategy (Davis-Kean, 2005) but also because parental education is the dimension of class that is the most pertinent to the study of achievement. Further, parental education may reflect parents' ability to help with schoolwork as well as the importance they place on academic achievement (Muller & Kerbow, 1993).

Parent education may also moderate the link between parent-adolescent relationship quality and academic achievement. An ecological perspective (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Bronfenbrenner & Crouter, 1983) posits that the same family processes may have different implications across different ecologies. Hughes and Perry-Jenkins (1996), for example, proposed that families assign different meanings and values to their behaviors and life circumstances as a function of social class. Thus, parents' reactions to their adolescents' academic achievement may differ depending on parents' own educational backgrounds. For example, parents with more education may set higher expectations for their adolescents' achievement. When adolescents do not reach these expectations, parents may react negatively.

Study Goals

In the present study, we examined longitudinal associations between parent-adolescent conflict and academic achievement. In the models we estimated, baseline levels of the dependent variables (conflict or academic achievement) were controlled, which allowed us to examine the extent to which relationship quality predicted relative increases or decreases in academic achievement as well as the extent to which academic achievement predicted relative changes over time in relationship quality. Grades in English and math were used as indicators of academic achievement because most students took these subjects and because they represent verbal and quantitative domains of academic competence that are important areas of aptitude with regard to college admissions.

Our first question was: Controlling for academic achievement at about age 15, does parent-adolescent conflict at that age predict subsequent academic achievement two years later? We predicted that parent-adolescent conflict would be related to relative declines in academic achievement. We were also interested in whether the associations between parent-adolescent relationship quality and academic achievement differed as a function of SES, as measured by parental education. We reasoned that the benefits of having better educated parents might buffer the negative effects of high levels of parent-adolescent conflict.

Our second question was: Controlling for parent-adolescent conflict at about age 15, does academic achievement at that age predict subsequent parent-adolescent conflict at about age 17? Our hypothesis was grounded in research showing that parent-adolescent relationships are shaped, in part, by adolescent behaviors (e.g., Kerr & Stattin, 2003; Melby & Conger, 1996). We expected that low achievement would trigger tensions between adolescents and their parents that would be manifested in increased conflict. Again, we were interested in the extent to which SES moderated the relation between academic achievement and parent-adolescent conflict. Although we did not have a priori hypotheses regarding how parental education might moderate the link, we reasoned that these processes could operate in two ways. On the one hand, academic achievement may be more salient in families with high levels of education such that parents are more responsive to adolescent academic performance, responding to poor performance with increased conflict. On the other hand, parents with less education may be more likely to use harsh parenting practices and respond with increased conflict when adolescents do not perform well in school.

Method

Participants

The original sample consisted of 197 dual-earner families with adolescent offspring participating in a longitudinal study of family relationships and adolescent development. Letters were sent home to families of 8th - 10th graders recruited from school districts in the central region of a northeastern state inviting families to participate in a research study of family life in the 1990's and asking eligible families to return a self-addressed postcard indicating their interest in participation. Eligible families met the following criteria: The firstborn adolescent was in one of the targeted grades and had at least one sibling 1 to 4 years younger, and families were maritally intact. In addition, we sought families in which both parents were employed at least part time. The original sample (N = 197) was composed primarily of working- and middle-class families from small cities, towns, and rural areas. Financial restrictions precluded us from requesting return postcards from all families whether or not they fit our criteria. Thus, we could not establish the response rate of eligible families. We do know, however, that of the eligible families who returned postcards indicating tentative interest, over 90% agreed to participate once they had discussed the study with project staff.

Our analyses focused on 168 families in which adolescents had complete academic achievement data at Time 1 and Time 2. When the adolescents who did not have Time 2 English achievement data were compared to the rest of the sample, we found that these adolescents were more likely to have higher father-adolescent conflict at Time 1 relative to others in the sample, t (10.6) = 2.54, p < .05. Adolescents who were missing math achievement data at Time 2 did not differ from others in the sample on any of the variables in the present study.

Time 1 data were collected between September 1995 and January 1996; Time 2 data were collected two years later. Participants were mothers, fathers, and their firstborn adolescents from working/middle class families residing in small cities, towns, and rural areas. Reflecting the demographic composition of the geographic area in which they resided, all families were European-American with the exception of 4 biracial (i.e., African-American/European-American) families. At Time 1, average family size was 4.60 people (SD = .82). On average, at Time 1 mothers had completed 14.33 years of education (SD = 2.09), and fathers had completed 14.28 years of education (SD = 2.29). At Time 1, adolescents (97 boys and 71 girls) averaged 14.90 years of age.

Procedures

At each measurement occasion, mothers, fathers, and adolescents were interviewed separately in their home about their personal qualities and family relationships. Informed consent was obtained from each family member, and the family received a $100 honorarium. Visits averaged 2 hours in duration and family members participated in face-to-face semi structured interviews and completed self-report questionnaires.

Measures

Parental education

We operationalized social class as the mean of parents' educational levels because this is a family-level variable that not only reflects access to resources, but also the attitudes, values, and perspectives that accompany schooling. During the home interview, mothers and fathers each reported on their highest level of education obtained, which were significantly correlated r = .52, p < .001 (12 years = high school graduate; 16 years = college degree). Overall, 24.8% of participants held high school degrees, 43.5% had obtained some college, 9.5% held college degrees, and 20.2% had advanced degrees.

Parent-adolescent conflict

Parent-adolescent conflict was assessed with an 11-item measure of conflict adapted from Smetana (1988). Mothers and fathers reported how frequently they engaged in conflict with their adolescent in 11 domains (e.g., household chores, bedtime or curfew, school) on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 6 (several times a day). Cronbach's alphas were .81 and .85 for mother- and father-adolescent conflict at Time 1 and .79 and .81 for mother- and father-adolescent conflict at Time 2.

Academic achievement

Grades in English and math were recorded from adolescents' most recent report cards during the home interview. Letter grades in English and math were converted into numerical scores (0 to 4) such that higher scores signified higher grades.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Girls earned higher grades in English and math than boys, t (166) = 2.70, p < .01 for English; t (166) = 2.44, p < .01 for math. Mothers and fathers reported more conflict with sons than with daughters, t (166) = -2.68, p < .01 for mother-adolescent conflict; t (166) = -1.67, p = .09 for father-adolescent conflict.

Bivariate correlations and descriptive statistics for variables to be modeled are presented in Table 1. As shown, adolescents had somewhat higher grades in English and math when they came from families with more education. More mother-adolescent and father-adolescent conflict at Time 1 was significantly related to lower grades in English and math at Time 2. Similarly, lower grades in English and math at Time 1 were significantly related to more mother-adolescent and father-adolescent conflict at Time 2. Cross-time stability in mother-adolescent and father-adolescent conflict was reasonably high: r = .67, p < .001 for mothers and r = .61, p < .001 for fathers respectively. Cross-time stability in English (r = .35, p < .001) and math grades (r = .35, p < .001) was somewhat weaker.

Table 1. Bivariate Correlations and Descriptive Statistics (N = 168).

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Parental Education | – | ||||||||

| 2. | English Grade T1 | .14† | – | |||||||

| 3. | English Grade T2 | .32*** | .35*** | – | ||||||

| 4. | Math Grade T1 | .14† | .40*** | .27*** | – | |||||

| 5. | Math Grade T2 | .14† | .36*** | .55*** | .35*** | – | ||||

| 6. | Mom Conflict T1 | -.00 | -.37*** | -.24** | -.30*** | -.28*** | – | |||

| 7. | Mom Conflict T2 | -.02 | -.19** | -.28*** | -.28*** | -.31*** | .67*** | – | ||

| 8. | Dad Conflict T1 | .12 | -.24** | -.21** | -.16* | -.27*** | .62*** | .57*** | – | |

| 9. | Dad Conflict T2 | .08 | -.16* | -.17* | -.22** | -.24 | .45*** | .64*** | .61*** | – |

|

| ||||||||||

| M | 14.31 | 3.32 | 3.13 | 3.23 | 3.01 | 26.11 | 23.74 | 25.24 | 22.86 | |

| SD | 1.91 | .78 | 1.01 | .94 | .97 | 6.91 | 6.15 | 7.02 | 5.92 | |

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

At the bivariate level there was evidence of negative associations between parent-adolescent conflict at Time 1 and grades at Time 2, as well as associations between grades at Time 1 and parent-adolescent conflict at Time 2. However, these bivariate relations do not take into account previous levels of conflict or grades. In the next set of analyses, we examined the extent to which parent-adolescent conflict was related to grades in English and math at Time 2 after accounting for academic performance in English and math at Time 1. Thus, we attempted to predict relative change in grades over a two-year period. We then examined the extent to which grades at Time 1 were related to conflict at Time 2, after accounting for conflict at Time 1. These analyses attempted to predict change over and above a strong trend toward stability in conflict.

Analytic Strategy

Cross-lagged structural equation modeling was conducted using maximum likelihood estimation within the AMOS 6 statistical program (Arbuckle, 1994). Given our interest in the bi-directional effects of parent-adolescent conflict and academic achievement, a multivariate model was estimated in which conflict at Time 1 predicted English and Math grades at Time 2, and grades at Time 1 predicted conflict at Time 2. Unlike bivariate or regression analyses, this technique allowed us to examine these pathways simultaneously after accounting for the effects of all other variables in the model. Multiple-group models were estimated for girls and boys. Because model fit was not significantly worse when paths were constrained to be equivalent for girls and boys, the data for girls and boys were analyzed in a single model (χ2.difference = 15.99 df = 15, p = .31). Given that mother-adolescent and father-adolescent conflict were highly correlated at both Time 1 (r = .62, p < .001) and Time 2 (r = .64, p < .001), we averaged scores for mother-adolescent and father-adolescent conflict, a decision which resulted in a simpler, more parsimonious model. Variables were centered at their means for ease of interpretation.

Model Fit

Model fit was assessed by the obtained chi-square, Confirmatory Fit Index (CFI), Tucker Lewis Index (TLI), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). CFI values above .95, TLI values above .95, and RMSEA values below .05 are generally considered to indicate good fit. The overall model fit was good, χ2 (7, N = 168) = 9.29, p = .23, CFI = .99, TLI = .99, RMSEA = .04.

Predicting Academic Achievement with Parent-Adolescent Conflict

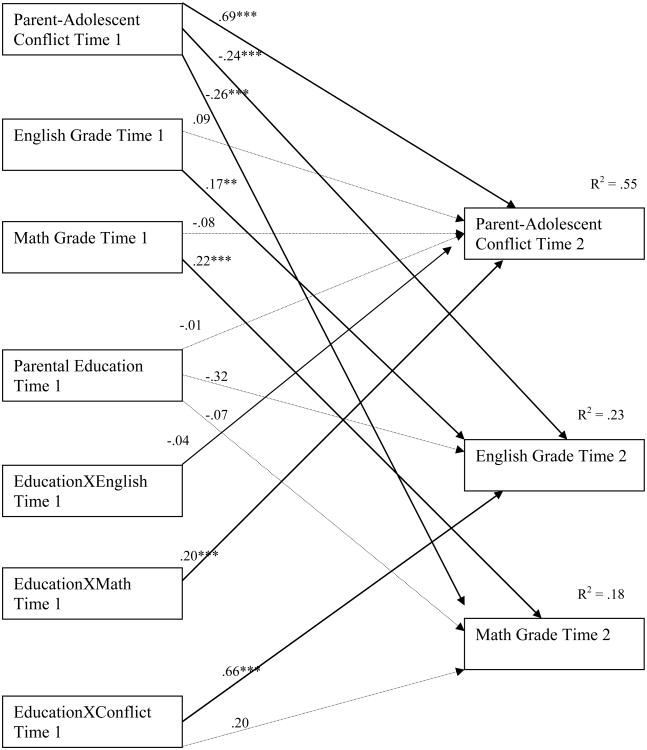

Our first question concerned the extent to which parent-adolescent conflict predicted English and math grades after controlling for previous achievement, as well as the extent to which parental education moderated this association. The standardized results of the structural equation model of cross-time conflict and grades are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Structural Equation Results for Parent-Adolescent Conflict and Academic Achievement.

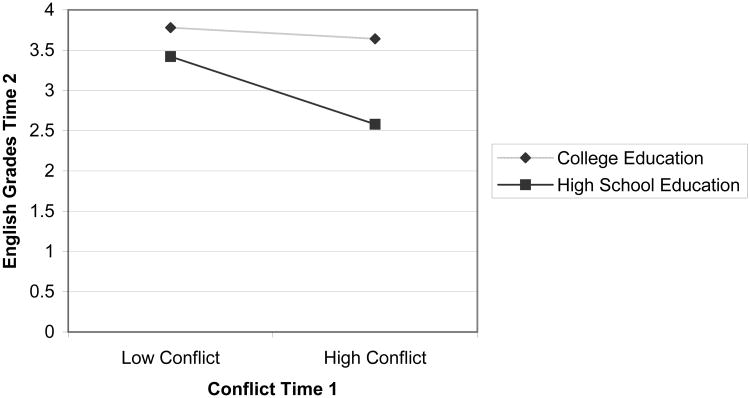

First, we examined stability in English and math grades over a two-year period. Reflecting the bivariate findings, English grades at Time 1 were significantly and positively related to grades in English at Time 2, and math grades at Time 1 were also significantly and positively related to math grades at Time 2. As expected, parent-adolescent conflict at Time 1 was significantly and negatively related to English and math grades at Time 2. Specifically, more parent-adolescent conflict at Time 1 was associated with relative declines in academic achievement at Time 2. The effect for English grades at Time 2, however, was qualified by a significant parental education by conflict interaction. Simple slopes, computed according to Aiken and West (1991), showed that adolescents had significantly lower Time 2 English grades when parent-adolescent conflict at Time 1 was higher and they came from families with less education. In contrast, this association was not significant for adolescents in better-educated families (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

English Grades at Time 2 as a Function of Parent-Adolescent Conflict and Parental Education at Time 1.

Predicting Parent-Adolescent Conflict with Academic Achievement

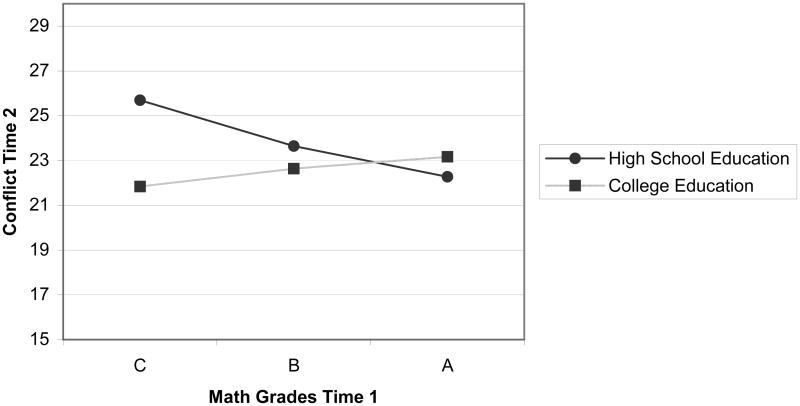

Next we examined the extent to which adolescent academic achievement at Time 1 predicted parent-adolescent conflict at Time 2. Parent-adolescent conflict at Time 1 was significantly and positively related to parent-adolescent conflict at Time 2. Contrary to our hypotheses, the main effects of Time 1 grades in English and math did not predict parent-adolescent conflict at Time 2. However, a significant interaction for parental education by Time 1 math grades emerged for parent-adolescent conflict. Lower grades in math at Time 1 were related to relative increases in conflict at Time 2 among families with less education. Simple slopes, computed according to Aiken and West (1991), showed that in families with less education, a one unit decrease in math grades was associated with a 2.38 unit increase in parent-adolescent conflict. In contrast, in families with more education, a one unit decrease in math grades was associated with a negligible 0.99 decrease in parent-adolescent conflict. We plotted these values for families with various levels of education (college degree vs. high school degree) and math grades at Time 1 (for A students versus B and C students). As shown in Figure 3, after accounting for average levels of conflict at Time 1, in families with less parental education, lower math grades at Time 1 were associated with increased conflict at Time 2. In contrast, in families with more education, lower math grades at Time 1 were associated with negligible decreases in conflict at Time 2.

Figure 3.

Parent-Adolescent Conflict at Time 2 as a Function of Math Grades and Parental Education at Time 1.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the longitudinal, bi-directional associations between parent-adolescent relationships and academic achievement during the high school years. As youth begin considering their post-high school plans, the high school years are a critical time for adolescent achievement. The adolescent years also coincide with changes in the parent-child relationship. Although few studies have examined longitudinal associations between parent-adolescent relationship quality, such as conflict, and academic achievement among older adolescents, in the present study, we followed a group of adolescents in 9th and 10th grades over a two-year period.

There are well-established links between parenting and achievement (Glasgow, 1997; Paulson, 1994; Steinberg, et al., 1992; Wentzel, 1994) but prior work is mostly on younger adolescents and is cross-sectional. Although some researchers propose that parental influence wanes in adolescence, the findings of Steinberg and colleagues provide evidence of the continuing influence parents have on adolescent achievement during the high school years. Our study adds to this literature by addressing the bi-directional nature of these associations over a two-year period.

Consistent with previous literature (Forehand, et. al., 1986; Melby & Conger, 1996), we found evidence that higher parent-adolescent conflict at Time 1 predicted subsequent lower adolescent academic achievement at Time 2. Researchers have documented declines in academic achievement across the adolescent years (Barber & Olsen, 2004; Eccles, Wigfield, & Schiefle, 1998), and our findings suggest that parent-adolescent conflict is one factor contributing to those declines. Disagreements between parents and adolescents are a normative aspect of adolescence and can be important for establishing independence, but parent-adolescent conflict also has negative implications for school performance as we found higher levels of parent-adolescent conflict predicted lower grades in English and math two years later. Problems at home can be distracting to adolescents and interfere with their performance at school. In addition, the lack of a supportive home environment may undermine youths' self-confidence and ability to take on challenging tasks that are necessary for school success.

We also found evidence that adolescent achievement has implications for parent-adolescent conflict at both the bivariate level and in our structural equation analyses, although this association was moderated by parental education. This finding is consistent with research on the bi-directionality of parent-adolescent relationships (Kerr & Stattin, 2003; Melby & Conger, 1996). Our results suggest that adolescent behaviors such as school performance help to shape the quality of parent-adolescent relationships. When adolescents struggle in school, it can be a source of stress and tension in the parent-adolescent relationship. Taken together, our findings that parent-adolescent conflict has implications for academic achievement and that academic achievement predicts later conflict support the notion that processes in one setting have implications for other settings (e.g., mesosystem linkages; Bronfenbrenner, 1979).

The importance of family interactions versus family background on youth's academic achievement has been somewhat debated in the literature. Our findings underscore the importance of examining the effects of family interactions as well as socioeconomic status on academic achievement (Dornbusch & Wood, 1989; Marjoribanks, 2005). We found that, for adolescents with less-educated parents, lower math grades were associated with increases in parent-adolescent conflict, but this pattern was not observed for adolescents with better-educated parents. Most parents want their children to do well in school, but parents from various educational backgrounds may express those expectations in different ways. It could be that parents with less education are more likely to use harsh parenting practices and react more strongly when their adolescent performs poorly. In their SES-Discipline Response Model, Pinderhughes and colleagues (2000) found that lower SES parents tended to endorse more harsh discipline responses. Further, Alexander and colleagues (1994) found a greater discrepancy between parents' expectations for performance and their children's actual school performance in families of lower socioeconomic status. Given the discrepancy between parents' beliefs about their child's performance and actual performance, parents with less education may react negatively when they find out that their children are not doing as well as they expect. Future research should examine parental beliefs and expectations as possible mediators of the relation between relationship quality and academic achievement.

This study is limited in terms of sample characteristics. Reflecting the demographic characteristics of the area from which families were drawn, participants were European American and working and middle class. Although we did find that parents' education level moderated the relation between parent-adolescent conflict and academic achievement, this finding needs to be replicated in a more economically diverse sample. The associations between parent-adolescent relationship conflict and academic achievement may also differ as a function of ethnicity or family structure, issues we were not able to examine here. Although Amato and Fowler (2002) did not find that the links between parenting practices and youth outcomes differed as a function of ethnicity, Fuligni (1998) found that Filipino adolescents were less likely to argue or talk back to their mothers and that both Filipino and Mexican American adolescents believed it was less acceptable to openly contradict their father than did European American adolescents. The value placed on achievement may also differ among ethnic groups and families from various socioeconomic backgrounds. An avenue for future research is to examine the bi-directional associations among parent-adolescent conflict and academic achievement in a more diverse sample.

This study's findings can be used to educate teachers, school counselors or family life educators to be aware that declines in academic achievement can be a source of tension in parent-adolescent relationships. In addition, it is important to disseminate to teachers and parents the fact that parent-adolescent relationship quality has implications for adolescents' academic achievement. These findings highlight a complex bi-directional process linking parent-adolescent conflict and academic achievement, School counselors and teachers can also help less-educated parents, in particular, to understand the increased academic pressures their adolescents are under in high school, to form realistic expectations, and to find ways to effectively help their adolescents through this period, especially when adolescents are facing challenging academic circumstances.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development (RO1-HD29409) to Ann Crouter and Susan McHale. The authors are grateful to their undergraduate and graduate student, staff, and faculty collaborators, as well as the dedicated families who participated in this project.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander KL, Entwisle DR, Bedinger SD. When expectations work: Race and socioeconomic differences in school performance. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1994;57:283–299. [Google Scholar]

- Allison B, Schultz J. Parent-adolescent conflict in early adolescence. Adolescence. 2004;39:100–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR, Fowler F. Parenting practices, child adjustment, and family diversity. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:703–716. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. AMOS: Analysis of moment structures. Psychometrika. 1994;59:135–137. [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK, Olsen JA. Assessing the transitions to middle and high school. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2004;19:3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Barton PE. Policy Information Report. Educational Testing Services; 2005. One-third of a nation: Rising dropout rates and declining opportunities. [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. Effects of authoritative parental control on child behavior. Child Development. 1966;37:887–907. [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. Parenting styles and adolescent development. In: Brooks-Gunn J, Lerner R, Petersen AC, editors. The Encyclopedia on Adolescence. New York: Garland; 1991. pp. 746–758. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RH, Corwyn RF. Socioeconomic status and child development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2002;53:371–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody G, Stoneman Z, Flor D. Linking family processes and academic competence among rural African American youths. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1995;57:567–579. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U, Crouter AC. The evolution of environmental models in developmental research. In: Mussen P, editor. The Handbook of Child Psychology. I. New York: Wiley; 1983. pp. 358–414. [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe R. Academic orientation and parental involvement in education during high school. Sociology of Education. 2001;74:210–230. [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe R. Social capital and the interplay of families and schools. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66:267–280. [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe R, Elder GH. Family dynamics, supportive relationships, and educational resilience during adolescence. Journal of Family Issues. 2004;25:571–602. [Google Scholar]

- Davis-Kean PE. The influence of parent education and family income on child achievement: The indirect role of parental expectations and the home environment. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:294–304. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.2.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dornbusch SM, Wood KD. Family processes and educational achievement. In: Weston WJ, editor. Education and the American Family. New York: New York University Press; 1989. pp. 66–95. [Google Scholar]

- Dubois D, Eitel S, Felner R. Effects of family environment and parent-child relationships on school adjustment during the transition to early adolescence. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1994;56:405–414. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan G, Yeung J, Brooks-Gunn J, Smith J. How much does childhood poverty affect the life chances of children? American Sociological Review. 1998;63:406–423. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles J, Wigfield A, Schiefle U. Motivation to succeed. In: Damon W, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Social, emotional, and personality development. 5th. Vol. 3. New York: Wiley; 1998. pp. 1017–1095. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Identity, youth, and crisis. New York: W. W. Norton; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Forehand R, Long N, Brody G, Fauber R. Home predictors of young adolescents' school behavior and academic performance. Child Development. 1986;57:1528–1533. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1986.tb00477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni A. Authority, autonomy, and parent-adolescent conflict and cohesion: A study of Adolescents from Mexican, Chinese, Filipino, and European backgrounds. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:782–792. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.4.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow K, Dornbusch S, Troyer L, Steinber L, Ritter P. Parenting styles, adolescents' attributions, and educational outcomes in nine heterogeneous high schools. Child Development. 1997;68:507–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall GS. Adolescence: Its psychology and its relations to physiology, anthropology, sociology, sex, crime, religion, and education. New York: D. Appleton; 1904. Preface (Vol. 1: pp v-xx) and Chapter X (Vol. 2: pp 40-94) [Google Scholar]

- Henderson VL, Dweck CS. Motivation and achievement. In: Feldman SS, Elliott GR, editors. At the threshold: The developing adolescent. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1990. pp. 308–329. [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck GN. A model of family relational transformations during the transition to adolescence: Parent-adolescent conflict and adaptation. In: Graber JA, Brooks-Gunn J, editors. Transitions through adolescence: Interpersonal domains and context. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1996. pp. 167–199. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes R, Perry-Jenkins M. Social class issues in family life education. Family Relations. 1996;45:175–182. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs J, Lanza S, Osgood W, Eccles J, Wigfield A. Changes in children's self- competence and values: Gender and domain differences across grades one though twelve. Child Development. 2002;73:509–527. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr M, Stattin H. Parenting of adolescents: Action or reaction? In: Crouter AC, Booth A, editors. Children's Influence on Family Dynamics: The Neglected Side of Family Relationships. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2003. pp. 121–151. [Google Scholar]

- Klebanov PK, Brooks-Gunn J, Duncan GJ. Does neighborhood and family poverty affect mothers' parenting, mental health, and social support? Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1994;56:441–455. [Google Scholar]

- Masten A, Coatsworth J. The development of competence in favorable and unfavorable environments: Lessons learned from research on successful children. American Psychologist. 1998;53:205–220. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marjoribanks K. Family environments and children's outcomes. Educational Psychology. 2005;25:647–657. [Google Scholar]

- Melby J, Conger RD. Parental behaviors and adolescent academic performance: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1996;6:113–137. [Google Scholar]

- Montemayor R. Parents and adolescents in conflict. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1983;3:83–103. [Google Scholar]

- Muller C, Kerbow D. Parent involvement in the home, school, and community. In: Schneider B, Coleman J, editors. Parents their Children, and Schools. Boulder, CO: Westview Press; 1993. pp. 13–42. [Google Scholar]

- Noller P. Relationships with parents in adolescence: Process and outcome. In: Montemayor R, Adams GR, Gullotta TP, editors. Personal Relationships During Adolescence. Vol. 6. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. pp. 37–77. [Google Scholar]

- Parke R, Buriel R. Socialization in the family: Ethnic and ecological perspectives. In: Damon W, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of child psychology, Vol 4 Social, emotional, and personality development. New York: John Wiley; 1998. pp. 463–552. [Google Scholar]

- Paulson SE. Relations of parenting style and parental involvement with ninth-grade students' achievement. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1994;14:250–267. [Google Scholar]

- Pinderhughes EE, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Discipline responses: influences of parents' socioeconomic status, ethnicity, beliefs about parenting, stress, and cognitive-emotional processes. Journal of Family Psychology. 2000;14:380–400. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.14.3.380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Graham P, Chadwick F, Yule W. Adolescent turmoil: Fact or fiction? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1976;17:35–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1976.tb00372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacker A, Schoon I, Bartley M. Social inequality in educational achievement and psychosocial adjustment throughout childhood: Magnitude and mechanisms. Social Science and Medicine. 2002;55:863–880. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00228-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiller K, Khmelkov V, Wang X. Economic development and the effects of family characteristics on mathematics achievement. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:730–742. [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG. Concepts of self and social convention: Adolescents' and parents' reasoning about hypothetical and actual family conflict. In: Gunnar MR, Collins WA, editors. Minnesota Symposia on Child Psychology, Vol 21: Development during the transition to adolescence. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1988. pp. 79–122. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. Autonomy, conflict, and harmony in the family relationship. In: Feldman SS, Elliott GR, editors. At the threshold: The developing adolescent. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1990. pp. 255–276. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Lamborn SD, Dornbusch SM, Darling N. Impact of parenting practices on adolescent achievement: Authoritative parenting, school involvement, and encouragement to succeed. Child Development. 1992;63:1266–1281. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wentzel K. Family functioning and academic achievement in middle school. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1994;14:268–291. [Google Scholar]