Abstract

Introduction:

Afatinib is an effective first-line treatment in patients with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-mutated non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and has shown activity in patients progressing on EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). First-line afatinib is also effective in patients with central nervous system (CNS) metastasis. Here we report on outcomes of pretreated NSCLC patients with CNS metastasis who received afatinib within a compassionate use program.

Methods:

Patients with NSCLC progressing after at least one line of chemotherapy and one line of EGFR-TKI treatment received afatinib. Medical history, patient demographics, EGFR mutational status, and adverse events including tumor progression were documented.

Results:

From 2010 to 2013, 573 patients were enrolled and 541 treated with afatinib. One hundred patients (66% female; median age, 60 years) had brain metastases and/or leptomeningeal disease with 74% having documented EGFR mutation. Median time to treatment failure for patients with CNS metastasis was 3.6 months, and did not differ from a matched group of 100 patients without CNS metastasis. Thirty-five percent (11 of 31) of evaluable patients had a cerebral response, five (16%) responded exclusively in brain. Response duration (range) was 120 (21–395) days. Sixty-six percent (21 of 32) of patients had cerebral disease control on afatinib. Data from one patient with an impressive response showed an afatinib concentration in the cerebrospinal fluid of nearly 1 nMol.

Conclusion:

Afatinib appears to penetrate into the CNS with concentrations high enough to have clinical effect on CNS metastases. Afatinib may therefore be an effective treatment for heavily pretreated patients with EGFR-mutated or EGFR–TKI-sensitive NSCLC and CNS metastasis.

Keywords: Afatinib, ErbB family blocker, Central nervous system metastasis, Non–small-cell lung cancer, Compassionate use program

Non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the leading cause of cancer-related death in many countries.1 The prognosis for advanced-stage disease has improved in the last two decades; however, with a 5-year survival rate of only approximately 15% the treatment of this disease remains a clinical challenge.1 In a subset of lung adenocarcinoma, somatic mutations of the gene encoding the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), in particular those clustering in exons 19 and 21, result in the expression of a structurally altered receptor and oncogenic activation of signaling pathways. Mutations in the EGFR gene define tumors in which cell survival is driven by and dependent on EGFR pathway signaling.2 EGFR-gene mutations are found in 10 to 15% of white patients and up to 60% of Asian patients, especially never-smokers and patients with adenocarcinoma. In addition, an over expression of EGFR has been detected in 40 to 80% of NSCLC patients.3–5

Clinical trials have demonstrated that first-line treatment with reversible EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), such as gefitinib or erlotinib, leads to improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) when compared with chemotherapy.6–10 However, despite good initial responses, patients with EGFR-mutated NSCLC go on to develop TKI resistance and disease progression after a median duration of 8 to 10 months on therapy.11

Small-molecule inhibitors with higher binding affinity and a broader target profile may improve treatment efficacy and delay the development of treatment resistance in EGFR-mutated NSCLC.12–14 Afatinib is an orally available, irreversible ErbB family (EGFR/ErbB1, human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 [HER2; ErbB2], and ErbB4) blocker approved in the European Union, United States, and several Asian and Latin American countries for TKI-naive patients with EGFR-mutated NSCLC.15,16 In contrast to the reversible EGFR-TKIs erlotinib and gefitinib, afatinib has been shown to bind covalently to the ErbB receptor in vitro, irreversibly blocking signaling and leading to sustained antimitogenic activity. Two large randomized clinical trials (LUX-Lung 3 and LUX-Lung 6) have demonstrated that afatinib prolongs PFS to an average of 13.6 months in patients with EGFR exon 19 deletion or exon 21 L858R mutation in the first-line setting. In addition, the LUX-Lung 1 trial in patients pretreated with reversible TKIs and platinum-based chemotherapy showed a median PFS of 3.3 months with afatinib monotherapy compared with 1.1 months for patients treated with placebo plus best supportive care. The LUX-Lung trials allowed enrolment of patients with stable brain metastases (BM). A recently reported analysis of 35 patients with BM from LUX-Lung 3 treated first line with either afatinib or cisplatin/pemetrexed showed a median PFS of 11.1 months on afatinib compared with 5.4 months for those treated with chemotherapy (hazard ratio [HR], 0.52; p = 0.13). This finding is of high clinical relevance as the central nervous system (CNS) is a common site of metastatic spread in NSCLC, with BM and/or leptomeningeal disease (LD) affecting 21 to 64% of patients during the course of disease,17–20 and 10 to 20% of patients at the time of first diagnosis.21 CNS metastasis limits the prognosis of patients with NSCLC,17 with a median survival of only 1 month without treatment,22 2 months with glucocorticoid therapy, and 2 to 5 months with whole brain radiation therapy.23–27 In addition to limiting survival, CNS metastases often cause neurological symptoms and a decrease in quality of life.28

The introduction of targeted therapies such as EGFR-TKIs has broadened the therapeutic options available to NSCLC patients with activating EGFR mutations.29,30 EGFR-TKIs are now recommended for first-line treatment of patients with EGFR mutation-positive NSCLC.12 However, data on the efficacy and cerebral bioavailability of EGFR-TKIs in patients with CNS metastasis remain limited.

The afatinib compassionate use program (CUP) was initiated in May 2010 after availability of the results of the LUX-Lung 1 trial,31,32 and was intended to provide access to afatinib for patients progressing on erlotinib or gefitinib. Here we present an analysis of treatment efficacy in patients with BM who were treated with afatinib during this CUP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Afatinib CUP

Participation in the afatinib CUP was available to patients with advanced NSCLC who were ineligible to participate in another actively accruing afatinib trial and who had failed at least one line of platinum-based chemotherapy and progressed following at least 24 weeks on erlotinib or gefitinib. Additional inclusion criteria were age 18 years or older, absence of an established treatment option, and written informed consent. The intention of this CUP was to provide controlled preregistration access to afatinib for patients with life-threatening diseases and no other treatment option.

Afatinib was given as a continuous oral treatment at a starting dose of 50 mg/day. Lower starting doses of 40 or 30 mg were allowed at the discretion of the treating physician. Dose modifications (10-mg steps, maximum dose: 50 mg/day, minimum dose: 30 mg/day) were allowed. One treatment cycle was defined as 30 days. The protocol was approved by the responsible ethics committee (Medical Board of the State Rhineland-Palatine, 837.105.10[7114]), and the required regulatory authorities (BfArM and regional authorities) were informed. As required by regulations, the CUP was stopped with the availability of afatinib (GIOTRIF®) on the market.

Within the CUP participating physicians were asked to provide a pseudonymized clinical data set for each patient including gender, age, comorbidities, disease stage, prior therapies, and EGFR mutation status. This information was used to confirm patient eligibility for the CUP. Reporting of adverse events including tumor progression was mandatory. Physicians with patients known to have CNS involvement were approached to collect further data on BM, LD, radiation, and outcome.

Pharmacokinetic Analyses

One patient consented to pharmacokinetic analyses of blood and cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) samples. Blood samples were collected in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid drawing tubes. Validated bioanalytical assays for the determination of afatinib in human ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid plasma and in human CSF (with 1% citric acid added to prevent adsorption loss) were used for sample analysis.33,34 Afatinib was analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS) using isotope-labeled afatinib as internal standard. Solid-phase extraction was performed on plasma samples before the extract was injected onto the HPLC-MS/MS instrument. CSF samples were injected directly without a prior extraction step. Chromatographic and mass spectrometric conditions were identical for both matrices. Samples were subjected to chromatography on a reversed-phase analytical HPLC column with gradient elution. Afatinib and internal standard were detected by MS/MS using electrospray ionization in the positive mode. Calibration ranges were linear from 0.500 to 250 ng/ml for plasma and from 0.100 to 20.0 ng/ml for CSF, respectively. The analyses met all acceptance criteria.

Matched Patients

Each patient with CNS metastasis was matched with one patient from the CUP without CNS metastasis for age, gender, histology, mutational subgroup, median treatment duration with reversible EGFR-TKI, and treatment line.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive analysis was performed for patient demographics. Time to treatment failure (TTF) was defined from start of afatinib treatment (if not reported it was calculated as 7 days after shipment) to end of treatment stop (if not reported the date of the last order was used). Systemic response was defined as a response of both the primary tumor and metastasis outside the CNS. General response was defined as a response of the primary tumor and of all metastases including those in the CNS. The database was locked on December 31, 2013 and patients on treatment were censored. Survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method for TTF and overall survival. A Cox model was applied to estimate HRs and 95% confidence intervals with significance set at p value less than 0.05. Analyses were undertaken using MedCalc for Windows, version 12.1.4.0 (MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium). Patients who received less than 2 months of afatinib due to progressive disease (PD) or death were classified “PD” as best response, whereas patients receiving treatment for a period of more than 4 months were classified “stable disease” (SD) as best response if not reported differently.

RESULTS

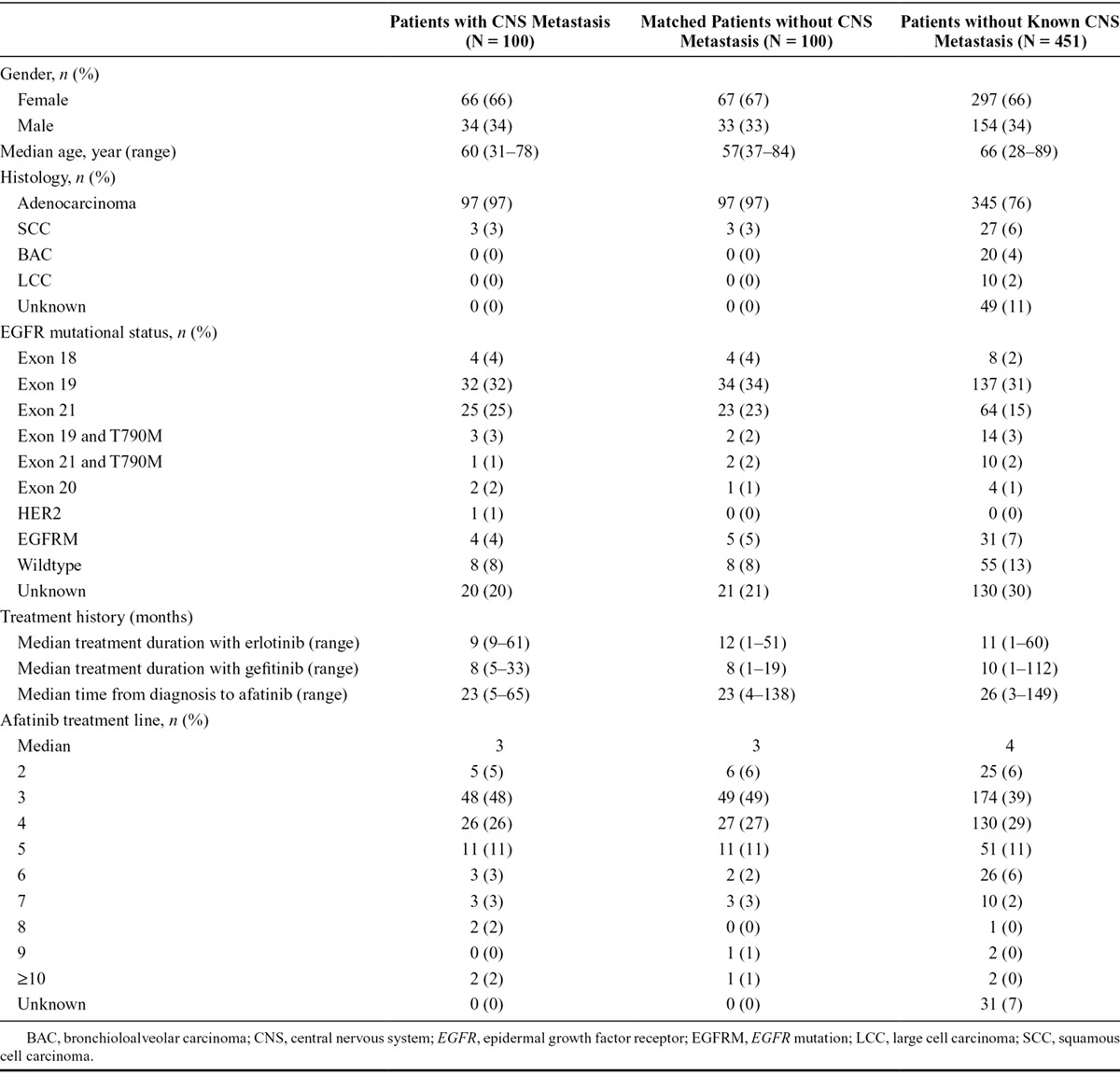

Between May 2010 and December 2013, 573 patients were included in the CUP and 541 were treated with afatinib.35 One hundred patients (66% female; median age, 60 years; range, 31–78 years) were reported to have either BM or LD (Table 1). Of those 97% had adenocarcinoma, 74% were reported to have an EGFR mutation confirmed by molecular pathology, and 77% of the reported EGFR mutations were exon 19 deletions or exon 21 L858R mutations. Seventy-two percent of patients with CNS metastasis also had bone metastasis. The patients were matched for analyses with 100 comparable NSCLC patients without CNS metastasis.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the Patients with and without CNS Metastasis and of the Matched Group without CNS Metastasis

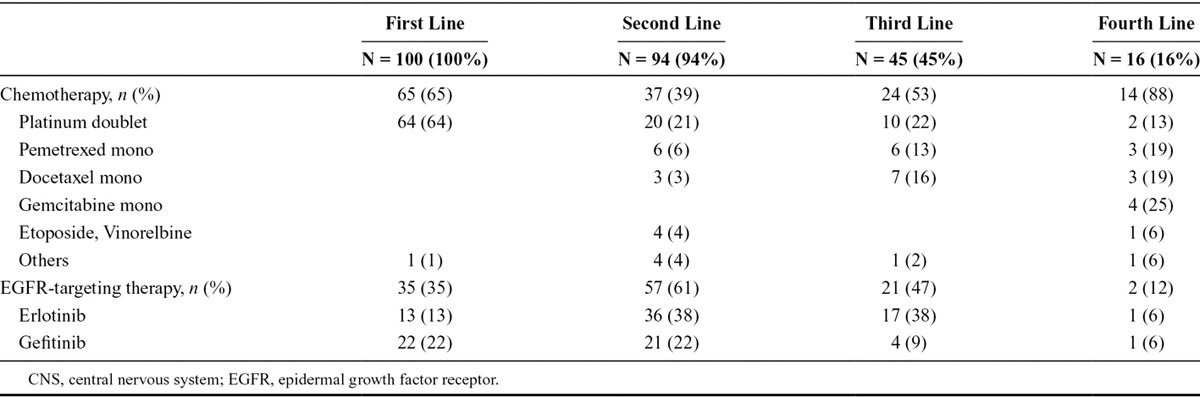

All patients in the CUP were pretreated with chemotherapy and erlotinib/gefitinib; first-line therapy was a platinum doublet in the majority (64%), and erlotinib (13%) and gefitinib (22%) in a subset (Table 2). The most common second-line treatments were erlotinib (38%) and gefitinib (22%), and 38% of patients received erlotinib in third-line. The majority of patients were enrolled in the CUP for third-line or fourth-line treatment, but individual patients with up to 12 prior treatment lines were also registered.

TABLE 2.

Pretreatment of the Patient Group with CNS Metastasis

The CUP protocol suggested a starting dose of 50 mg afatinib daily; however, this dose could be modified by the treating physician depending on side effects during prior EGFR-TKI treatment and the patient’s general performance status. Accordingly, starting doses were 50 mg (n = 71), 40 mg (n = 25), and 30 mg (n = 4). Dose reductions from 50 to 40 mg were carried out in 51% of patients, and from 40 to 30 mg in 80%. The main reasons for dose reductions were diarrhea (70% of dose reductions) and skin rash (24%).

Efficacy of Afatinib in Pretreated Patients with CNS Metastases

We analyzed patients’ previous response to treatment with erlotinib or gefitinib before their inclusion in the CUP. Patients with CNS metastases had been treated with erlotinib or gefitinib for a median of 9 months (range, 1–36 months). Data on general best response were available for 68 of these patients: 18% (12 of 68) had experienced a partial remission (PR), 53% (36 of 68) had SD, and 29% (20 of 68) had PD. Detailed information about the first diagnosis of CNS metastases was available for a subset of patients. Twenty-four percent (11 of 46) were reported to have developed CNS metastases after treatment with reversible TKIs. CNS metastases were first detected by computed tomography (CT) in 29%, by positron emission tomography-CT in 4%, and by magnetic resonance imaging in 67%. One patient had LD without further brain metastasis, 28% (10 of 36) had a solitary brain metastasis, 22% (8 of 36) had 2 to 5 brain metastases, and 47% (17 of 36) patients had more than five metastases in the CNS. Twenty-one percent (6 of 29) of patients had LD. Sixty-nine percent of patients were symptomatic from their CNS metastases, and 88% were treated with cranial radiation prior to afatinib therapy (36 of 41, median dose 30 Gy).

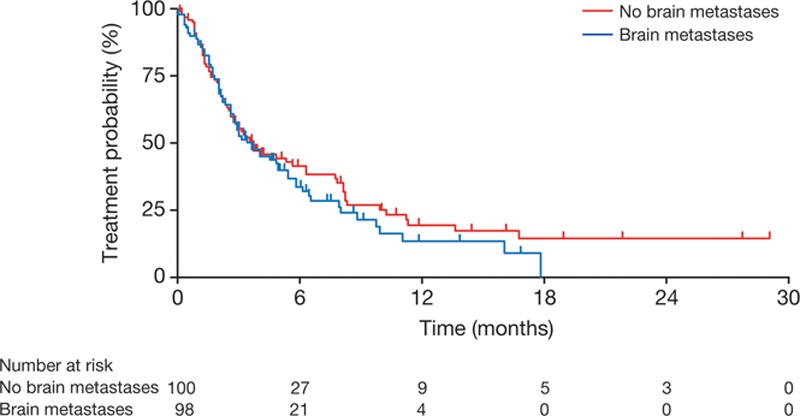

The clinical efficacy of afatinib was determined by calculating the TTF for each patient. TTF under afatinib in patients with CNS metastases was 3.6 months and did not differ from the TTF in matched patients without CNS metastases (HR, 1.16; 95% confidence interval, 0.83–1.62; p = 0.52; Fig. 1). TTF for patients with known EGFR mutations (n = 72) was 4.0 months, for patients with unknown mutational status (n = 20) 3.6 months, and for wild-type patients (n = 8) 1.3 months.

FIGURE 1.

Time to treatment failure.

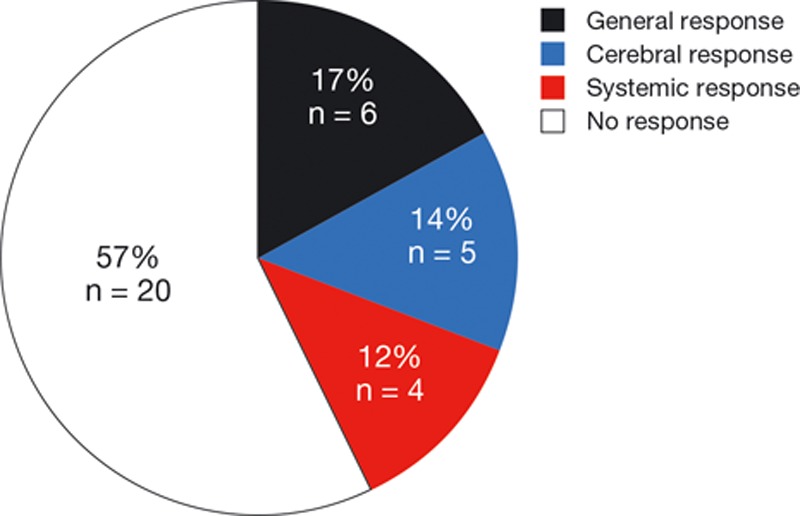

Most patients with CNS metastases benefited from treatment with afatinib. Forty-two percent (13 of 31) of the evaluable patients experienced a PR on afatinib, 39% (12 of 31) had SD, and only 19% (6 of 31) had PD (Fig. 2). The disease control duration was 4 months (range, 1–13 months). Nineteen percent (6 of 31) had a general response (defined as systemic and CNS response), 16% (5 of 31) had a cerebral response only, and 13% (4 of 31) had a systemic response only. Therefore, the overall rate of cerebral response to treatment with afatinib was 35%. Sixty-six percent (21 of 32) of patients had CNS disease control on afatinib, whereas 23% (8 of 35) had an isolated cerebral progression during treatment (Fig. 3; please note that data on recurrence pattern were not always fully reported). Afatinib was discontinued in 39% of patients due to progression, in 17% due to death, in 7% due to side effects, and in 3% due to patient request. Twelve percent of patients were lost to follow-up, and 22% of the patients remained on treatment with afatinib at the end of the CUP. Typical adverse events, including diarrhea, skin/mucosal toxicity, nausea/vomiting, and fatigue, were observed as expected based on previous experiences with afatinib.31,32 The overall survival (OS) was 9.8 months (31% maturity). There were no unexpected safety signals.35

FIGURE 2.

Response rates in the patient group with central nervous system metastasis on afatinib.

FIGURE 3.

Patterns of response to afatinib in the patient group with central nervous system metastasis.

Two cases of patients with CNS metastasis are of great interest and shall be described here in detail.

Case Report 1

In June 2011, a 59-year-old never-smoking woman was diagnosed with stage IV adenocarcinoma of the lung (cT2b pN2 M1a, PLE) and proof of an L858R exon 21 mutation of the EGFR gene. First-line gefitinib treatment led to a partial remission for a duration of 9 months and was followed by second-line therapy with two cycles of pemetrexed 500 mg/m2. In June 2012, the patient developed symptomatic peritoneal carcinomatosis, an ovarian mass, pulmonary, and bone metastases. A rebiopsy from the peritoneum showed 10 to 20% L858R/T790M-positive tumor cells. Subsequent therapy with four cycles of cisplatin (40 mg/m2, d1+8) and gemcitabine (1000 mg/m2, d1+8, q d22) resulted in a minor response for a further 6 months. She then developed leptomeningeosis carcinomatosa (cytological confirmation in the spinal fluid) and was hospitalized with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 3/4. The patient subsequently received a fourth-line therapy with afatinib 50 mg/day. After a few days the neurological symptoms regressed, the vomiting stopped, and the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status dramatically improved to 1/2 when the patient was discharged. Furthermore, the lung metastases were regressive with extension of a partial response according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors 1.1. One month after beginning afatinib therapy, there was no evidence of tumor cells in the spinal fluid.

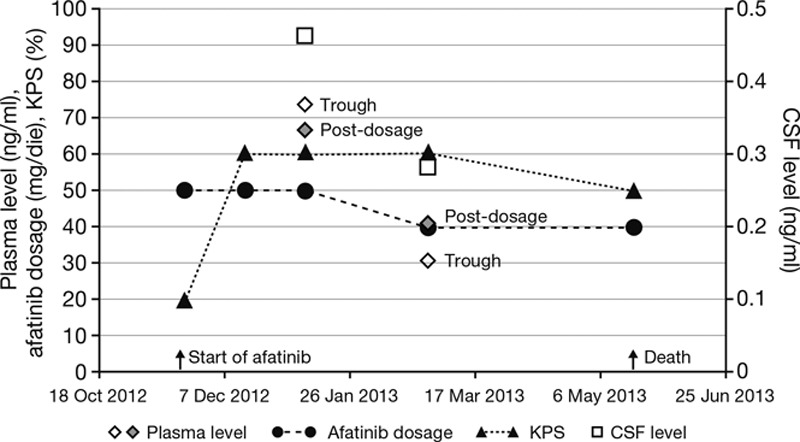

The plasma concentration of afatinib 3 hours after administration was 66.7 ng/ml BIBW 2992 base (BS; the free base of afatinib). The concentration of CSF 3 hours after administration was 0.464 ng/ml BIBW 2992 BS, which is equivalent to a concentration of approximately 1 nMol afatinib in the CSF (Fig. 4).

FIGURE 4.

Pharmacokinetic and clinical data from case report 1. CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; KPS, Karnofsky performance status.

Then the patient developed diarrhea and elevated liver transaminases (2–5 times upper limit of normal). The course of disease was complicated by acute renal failure after contrast media (for CT) in conjunction with moderate diarrhea. The dosage was reduced to 40 mg afatinib. In May 2013 (5 months after starting afatinib), the patient died of sepsis following an infection of the port-catheter without evidence of progression of the leptomeningeosis carcinomatosa.

Case Report 2

In February 2007, a 61-year-old male smoker was first diagnosed with stage IV adenocarcinoma of the lung and two cerebral metastases (pT4 pN1 M1b). After a bilobectomy and a cerebral metastasectomy, he received four cycles of cisplatin (40 mg/m2 d1+8)/vinorelbine (25 mg/m2 d1+8)/bevacizumab (15 mg/kg d1, q d29) and bevacizumab was continued up to June 2008. In January 2009, a bone metastasis was resected and irradiated (30 Gy) and a radiation of the brain was performed (30 Gy) followed by a second-line therapy with erlotinib. In March 2012, a metastasectomy of the right adrenal gland was performed with confirmation of an EGFR-wildtype in the resection specimen. One month later, the patient developed new cerebral and pulmonal metastases and third-line therapy with afatinib (50 mg/day) was initiated. The trough plasma concentration 7 weeks after the start of afatinib was 35.6 ng/ml; 3 hours after administration, it was 59.07 ng/ml BIBW 2992 BS. The patient experienced a partial response with little side effects (grade 1: diarrhea and rash). In January 2013, the dosage of afatinib was increased to 60 mg/day and in April 2013 to 70 mg/day at the discretion of the treating physician. In October 2013, after 16 months of treatment with afatinib, the patient died due to rapid tumor progression.

DISCUSSION

Heavily pretreated NSCLC patients with CNS metastases who progressed on erlotinib or gefitinib seemed to respond well to treatment with afatinib during a CUP. The rates of both systemic and CNS disease control were high. These results are encouraging, as CNS metastases negatively impact the quality of life and OS of many patients with NSCLC and continue to present a therapeutic challenge.36,37 In addition to the therapeutic effect of afatinib, the relatively long OS of patients with CNS metastases in the CUP may also reflect the prognostic relevance of EGFR mutations and a degree of preselection for patient motivation and general state of health.

Systemic chemotherapy is often ineffective in patients with CNS metastases, perhaps due to poor permeability of the blood–brain barrier to these agents.25,26 The cerebral efficacy of TKIs seems to be somewhat higher, and response rates of 75 to 89% in EGFR-mutated NSCLC patients with CNS metastases treated with EGFR-TKIs have been reported.38

A sequential approach to treatment in which patients with EGFR-mutated NSCLC and CNS metastases are offered a trial of TKI treatment, and brain irradiation is delayed until clinical or radiological progression occurs, may be reasonable,39,40 and could delay or prevent patient exposure to the side effects of cranial irradiation.41 However, in addition to evidence that TKIs are effective in patients with brain metastases, there is evidence that patients treated with EGFR-TKIs or anaplastic lymphoma kinase-TKIs over a period of many months may have an increased risk of developing CNS metastases.42 It may be that the concentration of TKI in the CSF is sufficient to inhibit treatment-naive, non–TKI-resistant cells, but that over time the lower drug concentrations select for resistant clones.

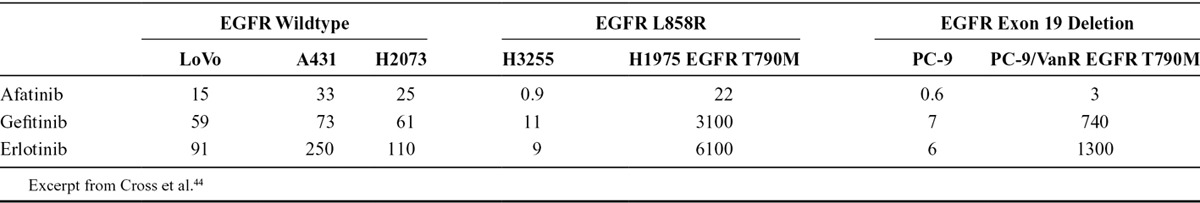

Due to its potency at relatively low concentrations, afatinib may remain effective in the CSF after resistance to other TKIs has developed. In preclinical studies, afatinib demonstrated high potency of kinase inhibition against EGFR, HER2, and ErbB4 kinases with 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 0.5, 14, and 1 nM, respectively.15,16,43 The median inhibitory concentration of afatinib (in vitro) is lower than that of currently available EGFR-TKIs (Table 3).15,44 This suggests that afatinib has the potential to treat CNS metastases effectively, despite incomplete penetration of the blood–brain barrier. The regression of CNS metastases observed during the afatinib CUP provides clinical evidence that afatinib concentration in the CSF is sufficient to inhibit tumor growth. Subgroup analyses of the LUX-Lung trials have also documented the effectiveness of first-line afatinib in the treatment of CNS metastases in EGFR-mutated NSCLC,45 and support the observations within the afatinib CUP. TTF in the CUP did not differ in patients with and without CNS metastases. Over 70% of the patients with CNS metastases had either PR or SD and 76% of the patients developed no new metastases.

TABLE 3.

IC50 Values of Reversible EGFR-TKIs and Afatinib

Therapy with erlotinib results in penetration into the CSF previously reported to range from 2.5% to 13%; and gefitinib concentration in the CSF has been reported to reach approximately 1% of serum levels.36,46,47 Very little is known about the ability of afatinib to penetrate into the CSF. The plasma and CSF concentrations of afatinib were measured in one patient in the CUP (see Case Report 1) and gave a CSF to plasma ratio of below 1%. Calculating the molar concentration would lead to a value of 0.95 nM, which is around the IC50 value for EGFR/ErbB1 (0.5 nM) and for HER4/ErbB4 (1 nM) but below the value for HER2 (14 nM).

The effective concentration of afatinib in CSF has not been described previously. Nevertheless, the correlation with dramatic clinical improvement and disappearance of tumor cells in the CSF suggests that the dose reached was sufficient to inhibit tumor growth. One could speculate that there are distribution processes in the CNS which could lead to higher concentrations at the target tissue. Afatinib has a high affinity to EGFR, which should be overexpressed in the tumor tissue and, thus, could be enriched there. It should also be considered that the protein content of CSF is much lower than that of blood, so ratios of the free (effective) concentrations would probably be higher.

By comparison, erlotinib levels in the CSF at approximately 5% of the plasma levels have been reported to be sufficient to inhibit the receptor, whereas gefitinib levels in the CSF (approximately 1% of plasma levels) have been reported to be insufficient for inhibition.36 The concentration of afatinib in the cerebrospinal fluid is nearly 1 nMol. Clearly some afatinib penetrates into the CNS, and achieves concentrations high enough to have a clinical effect. Dose modifications of afatinib based on individual tolerability reduced excessive afatinib plasma levels (as in case report 1), whereas experimental escalation up to 70 mg from an initial dose of 50 mg in case report 2 prolonged response. Case report 2 involved a trial of high-dose afatinib to treat progressing brain metastases. The patient remained on high-dose (70 mg/day) afatinib for 6 months. Cases involving the use of high-dose or pulsed EGFR-TKIs for the treatment of progressive brain metastases have been reported in the literature.48–50 Hata et al.50 gave erlotinib at a dose of 300 mg on alternating days and Dhruva and Socinski.49 gave 600 mg every 4 days. A case series involving 10 patients treated with pulsed erlotinib 1000 to 1500 mg once weekly was presented at the 2013 American Society of Clinical Oncology meeting but has to our knowledge not yet been published.48,51 The responses seen in these patients suggest that the efficacy of these TKIs in the brain may be limited by insufficient penetration of the drugs into the CSF and may be increased by increasing the dose. However, as clinical trial data supporting the use of these strategies is not yet available, the use of high-dose or pulsed TKIs should be considered experimental at this time.

In summary, heavily pretreated patients with EGFR-resistant NSCLC and CNS metastases benefited from treatment with afatinib in this CUP. In light of the lack of established treatment options in this setting, these results are particularly encouraging.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Editorial assistance was provided by Katie McClendon of GeoMed, part of KnowledgePoint360, an Ashfield Company, prior to submission of this article. Supported financially by Boehringer Ingelheim.

APPENDIX. THE AFATINIB COMPASSIONATE USE CONSORTIUM (ACUC) STUDY GROUP MEMBERS

The study group members are A. Abdollahi, A. Ammon, S.P. Aries, C. Arntzen, H.J. Achenbach, D. Atanackovic, A. Atmaca, N. Basara, D. Binder, B. Borchard, M. Bos, W. Brugger, S. Budweiser, K. Conrad, K. Corduan, D. Cortes-Incio, B. Dallmeier, C. Denzlinger, H.G. Derigs, N. Dickgreber, I. Dittrich, T. Düll, W. Engel-Riedel, M. Faehling, A. Fertl, J.R. Fischer, D. Fleckenstein, G. Folprecht, A. Forstbauer, Y. France, N. Frickhofen, S. Frühauf, M. Gardizi, T. Gauler, C. Gessner, W. Gleiber, E. Gökkurt, M. Görner, C. Grah, J. Greeve, J. Greiner, F. Griesinger, C. Grohé, W. Grüning, D. Guggenberger, S. Gütz, C. Hannig, D. Heigener, M. Heilmann, B. Heinrich, G. Hense, M. Hoiczyk, R.M. Huber, G. Illerhaus, G. Jacobs, P. Jung, K.O. Kambartel, L. Kayikci, J. Kern, J. Kersten, M. Kiehl, M. Kimmich, J. Kisro, H. Knipp, Y.D. Ko, J.U. Koch, C.H. Koehne, J. Kollmeier, A. Kommer, W. Körber, K. Kratz-Albers, G. Krause, R. Krügel, E. Laack, R. Leistner, U. Liebers, M. Lommatzsch, C. Maintz, C. Mozek, A. Matzdorff, M. Mohr, W. Neumeister, H. Nolte, T. Overbeck, M. Östreicher, J. Panse, T. Pelzer, K. Peters, M. Planker, A. Reissig, M. Ritter, A. Rittmeyer, S. Rösel, P. Sadjadian, B. Sandritter, M. Schatz, M. Scheffler, G. Schmid-Bindert, A. Schmittel, C.P. Schneider, W. Schneider-Kappus, F. Schneller, E. Schorb, J. Schreiber, F. Schüler, M. Schuler, A. Schulz-Abelius, C. Schumann, W. Schütte, S. Schütz, M. Schütz, M. Sebastian, M. Serke, D. Spissinger, W. Spengler, H. Staiger, U. Steffen, I. Stehle, H. Steiniger, K. Stengele, S. Steppert, J. Stöhlmacher-Williams, T. Strapatsas, B. Sulzbach, A. Tessmer, M. Thomas, B. Thöming, D. Ukena, B. Wagner, T. Wagner, D. Wagner-Hug, H. Wahn, T. Wehler, R. Wiewrodt, C. Witt, M. Wohlleber, J. Wolf, M. Wolf, K. Wricke, O. Zaba, and I. Zander.

Footnotes

Drs. Hoffknecht and Tufman contributed equally to this work.

Dr. Hoffknecht has participated in boards for Lilly Oncology and has received institutional grant support and compensation for travel expenses from Boehringer Ingelheim. Dr. Tufman has received compensation for lectures from Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Roche, and Novartis. Dr. Wehler has served as consultant and participated in boards and has received compensation for lectures and educational presentations from Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Roche, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Wiewrodt has participated in investigator-initiated trials for Bayer and Eli Lilly and advisory boards for Boehringer Ingelheim Grifols, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Roche, and Talecris. Dr. Wiewrodt has also received compensation for lectures and CME from Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, EuMeCom, Grifols, GlaxoSmithKline, Eli Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Talecris, UKM Academy, and ZDF. Dr. Schütz has participated in advisory boards for Boehringer Ingelheim. Dr. Serke has participated in boards and received compensation for lectures from Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, and Roche and has received honoraria for participation in review activities from Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Roche, AstraZeneca, and Amgen. Dr. Stöhlmacher-Williams has served as consultant and received compensation for lectures and previous manuscript preparation from Boehringer Ingelheim. Dr. Märten is a full-time employee of Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GmbH & Co KG. Dr. Huber has served as consultant for Boehringer Ingelheim and has received compensation for lectures from Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, and Pierre Fabre Pharma GmbH. Dr. Dickgreber has participated in boards for Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Roche, Novartis, and Bristol-Myers Squibb and has served as consultant and provided expert testimony for Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, and Roche. Dr. Pelzer declares no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shepherd FA, Rodrigues Pereira J, Ciuleanu T, et al. Erlotinib in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:123–132. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharma SV, Bell DW, Settleman J, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in lung cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:169–181. doi: 10.1038/nrc2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doroshow JH. Targeting EGFR in non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:200–202. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe058113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson BE, Jänne PA. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7525–7529. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pao W. Defining clinically relevant molecular subsets of lung cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2006;58(Suppl 1):s11–s15. doi: 10.1007/s00280-006-0310-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maemondo M, Inoue A, Kobayashi K, et al. Gefitinib or chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer with mutated EGFR. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2380–2388. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitsudomi T, Morita S, Yatabe Y, et al. Gefitinib versus cisplatin plus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor (WJTOG3405): an open label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:121–128. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70364-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:947–957. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosell R, Carcereny E, Gervais R, et al. Erlotinib versus standard chemotherapy as first-line treatment for European patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (EURTAC): a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:239–246. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70393-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou C, Wu YL, Chen G, et al. Erlotinib versus chemotherapy as first-line treatment for patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (OPTIMAL, CTONG-0802): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:735–742. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70184-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pao W, Balak MN, Riely GJ, et al. Molecular analysis of NSCLC patients with acquired resistance to gefitinib or erlotinib. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(Suppl 18):7078. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Druker BJ. Circumventing resistance to kinase-inhibitor therapy. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2594–2596. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe068073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kobayashi S, Boggon TJ, Dayaram T, et al. EGFR mutation and resistance of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:786–792. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lynch TJ, Adjei AA, Bunn PA, Jr, et al. Summary statement: novel agents in the treatment of lung cancer: advances in epidermal growth factor receptor-targeted agents. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(14 Pt 2):4365s–4371s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li D, Ambrogio L, Shimamura T, et al. BIBW2992, an irreversible EGFR/HER2 inhibitor highly effective in preclinical lung cancer models. Oncogene. 2008;27:4702–4711. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Solca F, Dahl G, Zoephel A, et al. Target binding properties and cellular activity of afatinib (BIBW 2992), an irreversible ErbB family blocker. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;343:342–350. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.197756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsiao SH, Chung CL, Chou YT, et al. Identification of subgroup patients with stage IIIB/IV non-small cell lung cancer at higher risk for brain metastases. Lung Cancer. 2013;82:319–323. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inukai M, Toyooka S, Ito S, et al. Presence of epidermal growth factor receptor gene T790M mutation as a minor clone in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7854–7858. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kobayashi S, Ji H, Yuza Y, et al. An alternative inhibitor overcomes resistance caused by a mutation of the epidermal growth factor receptor. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7096–7101. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nguyen T, Deangelis LM. Treatment of brain metastases. J Support Oncol. 2004;2:405–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sequist LV. Second-generation epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncologist. 2007;12:325–330. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-3-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zimm S, Wampler GL, Stablein D, et al. Intracerebral metastases in solid-tumor patients: natural history and results of treatment. Cancer. 1981;48:384–394. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19810715)48:2<384::aid-cncr2820480227>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eichler AF, Loeffler JS. Multidisciplinary management of brain metastases. Oncologist. 2007;12:884–898. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-7-884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fan Y, Huang Z, Fang L, et al. Chemotherapy and EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors for treatment of brain metastases from non-small-cell lung cancer: survival analysis in 210 patients. Onco Targets Ther. 2013;6:1789–1803. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S52172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khuntia D, Brown P, Li J, et al. Whole-brain radiotherapy in the management of brain metastasis. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1295–1304. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.6185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Langer CJ, Mehta MP. Current management of brain metastases, with a focus on systemic options. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6207–6219. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ruderman NB, Hall TC. Use of glucocorticoids in the palliative treatment of metastatic brain tumors. Cancer. 1965;18:298–306. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196503)18:3<298::aid-cncr2820180306>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee SJ, Lee JI, Nam DH, et al. Leptomeningeal carcinomatosis in non-small-cell lung cancer patients: impact on survival and correlated prognostic factors. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8:185–191. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182773f21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eichler AF, Kahle KT, Wang DL, et al. EGFR mutation status and survival after diagnosis of brain metastasis in nonsmall cell lung cancer. Neuro Oncol. 2010;12:1193–1199. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noq076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hirsch FR, Jänne PA, Eberhardt WE, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibition in lung cancer: status 2012. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8:373–384. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31827ed0ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller VA, Hirsh V, Cadranel J, et al. Phase IIb/III double-blind randomized trial of afatinib (BIBW2992), an irreversible inhibitor of EGFR/Her1 and Her2 plus best supportive care (BSC) versus placebo + BSC in patients with NSCLC failing 1–2 lines of chemotherapy and erlotinib or gefitinib (LUX-Lung 1). Ann Oncol. 2010;21:LBA1. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller VA, Hirsh V, Cadranel J, et al. Afatinib versus placebo for patients with advanced, metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer after failure of erlotinib, gefitinib, or both, and one or two lines of chemotherapy (LUX-Lung 1): a phase 2b/3 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:528–538. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.European Medicines Agency. Guideline on bioanalytical method validation. 2011. Available at: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2011/08/WC500109686.pdf. Accessed April 7, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry: bioanalytical method validation. 2013. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM368107.pdf. Accessed April 7, 2014.

- 35.Schuler M, Fischer JR, Grohé C, et al. Experience with afatinib in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer progressing after clinical benefit from gefitinib and erlotinib. Oncologist. 2014;19:1100–9. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Togashi Y, Masago K, Fukudo M, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid concentration of erlotinib and its active metabolite OSI-420 in patients with central nervous system metastases of non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:950–955. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181e2138b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park JH, Kim YJ, Lee JO, et al. Clinical outcomes of leptomeningeal metastasis in patients with non-small cell lung cancer in the modern chemotherapy era. Lung Cancer. 2012;76:387–392. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berger LA, Riesenberg H, Bokemeyer C, et al. CNS metastases in non-small-cell lung cancer: current role of EGFR-TKI therapy and future perspectives. Lung Cancer. 2013;80:242–248. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim JE, Lee DH, Choi Y, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors as a first-line therapy for never-smokers with adenocarcinoma of the lung having asymptomatic synchronous brain metastasis. Lung Cancer. 2009;65:351–354. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mok T, Yang JJ, Lam KC. Treating patients with EGFR-sensitizing mutations: first line or second line—is there a difference? J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1081–1088. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.0652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dropcho EJ. Neurotoxicity of radiation therapy. Neurol Clin. 2010;28:217–234. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee YJ, Choi HJ, Kim SK, et al. Frequent central nervous system failure after clinical benefit with epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in Korean patients with nonsmall-cell lung cancer. Cancer. 2010;116:1336–1343. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wind S, Schmid M, Erhardt J, et al. Pharmacokinetics of afatinib, a selective irreversible ErbB family blocker, in patients with advanced solid tumours. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2013;52:1101–1109. doi: 10.1007/s40262-013-0091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cross DAE, Ashton SE, Ghiorghiu S, et al. AZD9291, an irreversible EGFR TKI, overcomes T790M-mediated resistance to EGFR inhibitors in lung cancer. Cancer Discovery. 2014;4:1146–61. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sequist LV, Yang JC, Yamamoto N, et al. Phase III study of afatinib or cisplatin plus pemetrexed in patients with metastatic lung adenocarcinoma with EGFR mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3327–3334. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.2806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fukuhara T, Saijo Y, Sakakibara T, et al. Successful treatment of carcinomatous meningitis with gefitinib in a patient with lung adenocarcinoma harboring a mutated EGF receptor gene. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2008;214:359–363. doi: 10.1620/tjem.214.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Masuda T, Hattori N, Hamada A, et al. Erlotinib efficacy and cerebrospinal fluid concentration in patients with lung adenocarcinoma developing leptomeningeal metastases during gefitinib therapy. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2011;67:1465–1469. doi: 10.1007/s00280-011-1555-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jackman DM, Holmes AJ, Lindeman N, et al. Response and resistance in a nonsmall-cell lung cancer patient with an epidermal growth factor receptor mutation and leptomeningeal metastases treated with high-dose gefitinib. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4517–4520. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.6126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dhruva N, Socinski MA. Carcinomatous meningitis in nonsmall-cell lung cancer: response to high-dose erlotinib. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:e31–e32. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.0963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hata A, Kaji R, Fujita S, et al. High-dose erlotinib for refractory brain metastases in a patient with relapsed non-small cell lung cancer. JThorac Oncol. 2011;6 doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181d899bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jackman DM, Mach SL, Heng JC, et al. Pulsed dosing of erlotinib for central nervous system (CNS) progression in EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). ASCO Meeting Abstracts. 2013;31:8116. [Google Scholar]