Abstract

TAp73, a member of the p53 family, has been traditionally considered a tumor suppressor gene, but a recent report has claimed that it can promote cellular proliferation. This assumption is based on biochemical evidence of activation of anabolic metabolism, with enhanced pentose phosphate shunt (PPP) and nucleotide biosynthesis. Here, while we confirm that TAp73 expression enhances anabolism, we also substantiate its role in inhibiting proliferation and promoting cell death. Hence, we would like to propose an alternative interpretation of the accumulating data linking p73 to cellular metabolism: we suggest that TAp73 promotes anabolism to counteract cellular senescence rather than to support proliferation.

Keywords: p73, p53 family, senescence, aging, metabolism, apotosis, cancer

INTRODUCTION

Metabolic adaptation has emerged as a hallmark of cancer and a promising therapeutic target [1-9]. Rapidly proliferating cancer cells adapt their metabolism by increasing nutrient uptake and reorganizing metabolic fluxes to sustain biosynthesis of macromolecules necessary to achieve cell division and maintained redox and energy equilibrium [10-18]. It is increasingly evident that oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes regulate the metabolic rearrangement in cancer cells [19-23].

TAp73 acts as a tumor suppressor [24-27], at least partially through induction of cell cycle arrest and apoptosis [28] and through regulation of genomic stability [29, 30]. In addition, premature senescence is observed in TAp73 null mice suggesting that the presence of TAp73 is necessary to counteract senes-cence [31]. At least in part, this anti-senescence effect is mediated by a direct transcriptional effect of TAp73 on mitochondrial gene Cox4i1, hence regulating mitochondrial metabolism [31]. We also reported that TAp73 induces serine biosynthesis and glutaminolysis in lung cancer cells, via a direct transactivation of GLS2[32]. Interestingly, increased serine biosynthesis sustains cancer growth and has been recently reported to be nourished in breast cancer and melanoma by amplification of phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase gene [33, 34]. Recently, Du and colleagues [35, 36] reported that TAp73 triggers the expression of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD), the rate-limiting enzyme of the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), thus increasing flux through the PPP. By doing so, TAp73 diverts glucose to the production of NADPH and ribose, promoting synthesis of nucleotides and contributing to scavenging of reactive oxygen species [37]. The authors also describes that depletion of TAp73 leads to defective cellular proliferation, promptly rescued by G6PD expression or, alternatively, by addiction of nucleosides and ROS scavengers. Therefore, the authors conclude that TAp73 regulate metabolism with the ultimate result of promoting cell growth and proliferation, in striking contrast to its established role as tumor suppressor.

Prompted by these findings, we attempted to elucidate the regulation of cellular metabolism and proliferation by TAp73 using high throughput metabolomics study upon ectopic expression of TAp73βisoform in human p53-null osteosarcoma cell lines (SaOs-2). Moreover, we validated in-vitro findings, in brain tissue from TAp73 null mice. Here, we report that TAp73 promotes anabolic metabolism and nucleotide biosynthesis. Moreover, our data suggest that TAp73 promotes glycolysis and enhances the Warburg effect. Nonetheless, these changes are unlikely to lead to cell proliferation, as accompanied by robust upregulation of the cell cycle inhibitor p21 and marked apoptosis. Therefore, based on these and other findings we propose that TAp73-mediated control of cellular metabolism should be interpreted on the light of its multifaceted physiological activities, especially in the context of regulation of animal aging, fertility and neurodegerative diseases[31, 38-41]. We suggest that TAp73 promotes a metabolic reprogramming that act to protect from accelerated senescence and aging, as previously demonstrated[31, 42]. This interpretation will reconcile the findings of Du and colleagues with the abundant literature attributing a tumour suppressive function to TAp73.

RESULTS

TAp73 activates anabolic pathways

To investigate the effects of TAp73 expression on cellular metabolism, we used human p53/p73 null SaOs-2 osteosarcoma cell line, engineered to overexpress HA-tagged TAp73β isoform when cultured in the presence of the tetracycline analog doxycycline (Dox)[43] and used GC-MS and LC-MS-MS platforms to perform high throughput metabolomics [44]. With this approach, we unveiled an unexpected role for TAp73 in promoting the Warburg effect (manuscript in preparation). TAp73-expressing cells show an increased rate of glycolysis, higher amino acid uptake and increased levels and biosynthesis of acetyl-CoA (manuscript in preparation). Moreover, TAp73 expression increases the activity of several anabolic pathways including polyamine and membrane phospholipid synthesis (manuscript in preparation). In addition, nucleotide biosynthesis was significantly upregulated by TAp73. The biochemical analysis of intracellular nucleotides content is shown in Figures 1 and illustrates a sustained and significant upregulation of both purines and pyrimidines. Thus, our data indicate that TAp73 regulates multiple metabolic pathways that impinge on numerous cellular functions, but which, overall, converge to sustain “biochemical” cell growth and proliferation, in full agreement with the indicated report [35, 45].

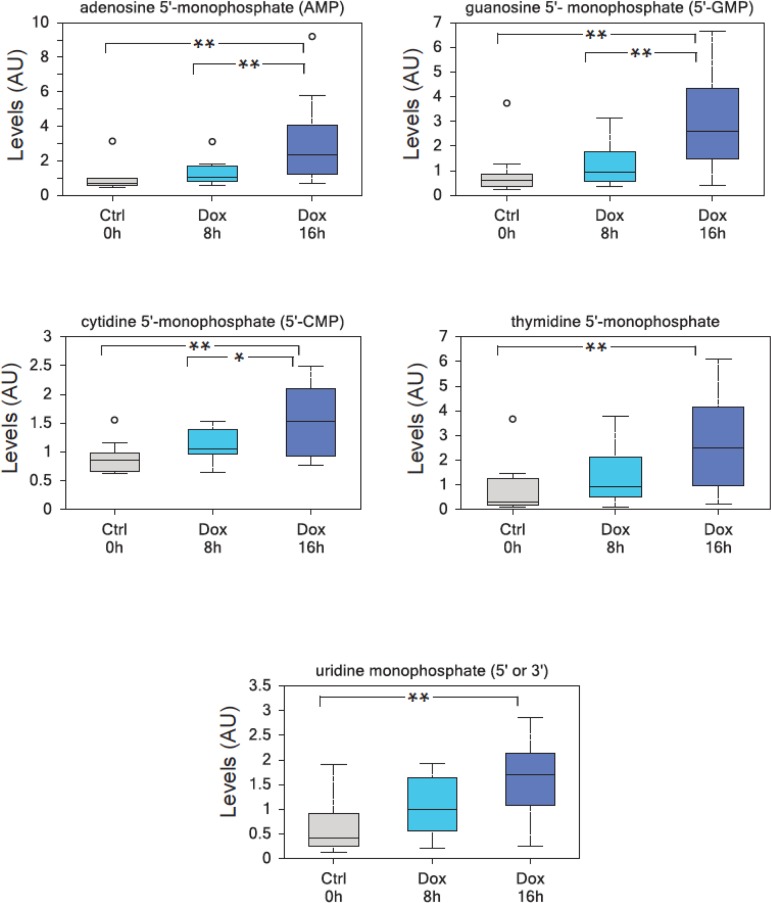

Figure 1. TAp73 overexpression induces nucleotide monophosphates.

TAp73β overxpression in SaOs-2 Tet-On cell lines results in a highly significant enrichment in all nucleotide monophosphates, consistent with an increased metabolic demand to sustain cell growth. (a) adenosine 5′-monophosphate (AMP), (b) guanosine 5′-monophosphate (5′-GMP), (c) cytidine 5′-monophosphate (5′-CMP), (d) thymidine 5′-monophosphate, (e) uridine monophosphate (5′ or 3′-UMP). Analysis was performed on thirty million cells per samples, 10 samples were analyzed for each time point (n=10). All the samples were extracted using standard metabolic solvent extraction methods and analyzed through GC/MS and LS/MS as previously described [44]. Box indicates upper/lower quartile, bars max/min of distribution. ** p<0.05; * 0.05<p<0.10.

p73 induces cell cycle arrest and cell death

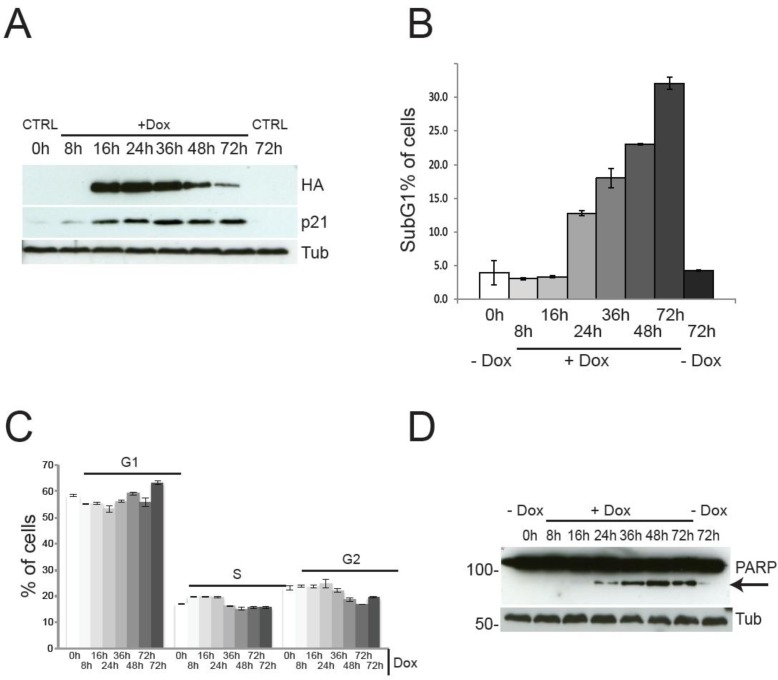

Although the described findings might be interpreted as suggestive of pro-proliferative function for TAp73, a careful analysis of the cell cycle profile indicates the complete absence of TAp73-induced proliferation. Indeed, Figure 2 shows the cell cycle and the cell death analysis at different time points. Expression of TAp73 β C-terminal isoforms reached plateau after 16h of Dox treatment, without any discernible effect on cell cycle distribution (Figure 2C), except for a mild increased in the G1 phase at 72h post-induction. Notwithstanding, expression of TAp73β was accompanied by a robust upregulation of the cell cycle inhibitor p21, evident already 8h after Dox administration (Figure 2D), strongly arguing against a proliferative role for TAp73. As expected, at later time points, the cells underwent programmed cell death, as previously described for TAp73 [43, 46]. Of note, the timing of the metabolomic analysis (blue arrows) was deliberately chosen before the onset of cell death, to avoid any confusion arising from metabolic changes associated with apoptosis. Overall, these data suggest that, although TAp73 expression stimulates anabolic pathways, it is unlikely to promote cellular proliferation, due to upregulation of the cell cycle inhibitor p21 and induction of apoptosis.

Figure 2. Cell cycle progression and cell death by TAp73β expression.

TAp73 overexpression in SaOs-2 Tet-On cell lines does not induce proliferation. (a) PARP1-cleavage (arrow) induced by TAp73β-expression confirms induction of cell death at 24h after doxycycline (2 μg/ml) addiction. (b) Cell death assessed by sub-G1 population after PI staining. Induction of cell death is evident only after 24h of TAp73 induction. Data indicate average of triplicates and standard deviation. Blue arrows indicate the time points used for metabolomics analysis (same cultures as shown here). (c) Cell cycle profile after induction of TAp73β determined by PI staining and cytofluorimetric analysis. Controls were left untreated (0h) or treated with vehicle for 72h to account for changes induced by confluence. Data indicate average of triplicates and standard deviation. Blue arrows indicate the time points used for metabolomics analysis (same cultures as shown here). (d) TAp73β and p21 expression were assessed by western blotting after treatment with doxycycline (2μg/ml) for the indicated times. TAp73 expression was detected using HA antibody to the N-terminal HA tag. Tubulin was used as loading control. Controls are as in Figure 1.

TAp73 depletion affects nucleotide metabolism in vivo

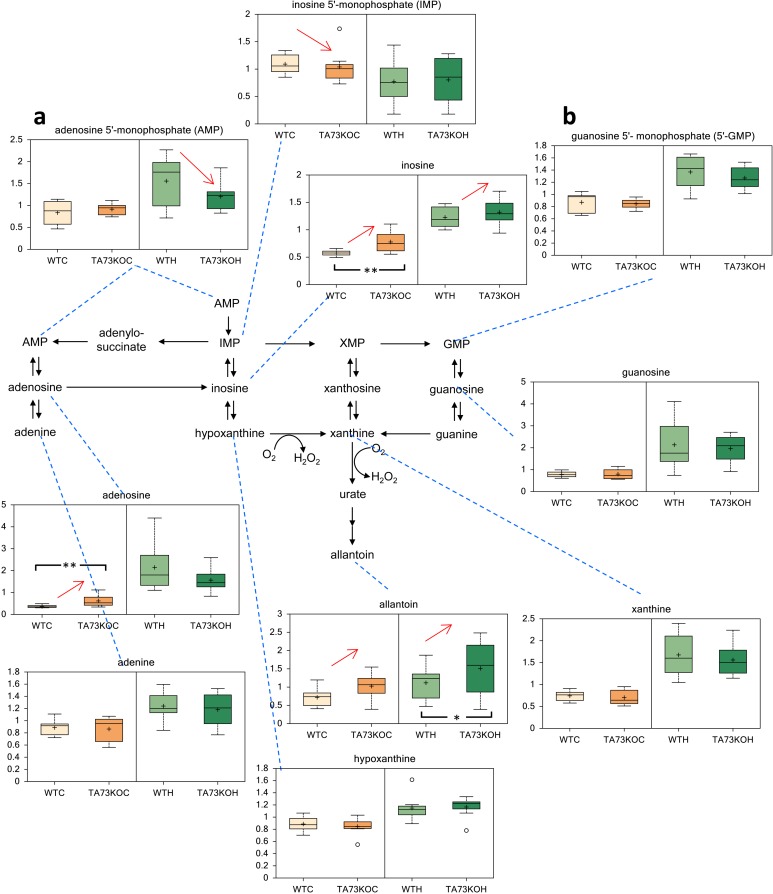

Since TAp73 exerts a relevant role in the physiology of the nervous system [38, 47-49], we analyzed cerebral cortex and hippocampus isolated from TAp73 wild-type (WT) and knockout (KO) animals [50] to question whether TAp73 regulates nucleotides metabolism in-vivo. Notably, in agreement with the in-vitro experiment, we found that purine metabolism was altered in TAp73KO brains. In particular, inosine and adenosine were significantly higher in the cortex of TAp73KO compared to WT controls. Moreover, allantoin, the final product in purine catabolism, was higher in both TAp73KO cortex and hippocampus, reaching statistical significance in the latter. On the other hand, inosine 5′- monophosphate and adenosine 5′- monophosphate were significantly reduced in the cortex and hippocampus of TAp73 KO mice, respectively. Hence, these data suggest that TAp73 regulates nucleotides metabolism in-vivo, in physiological context.

DISCUSSION

The identification of extensive metabolic re-arrangements that sustain cancer growth has spurred interest towards a deeper understanding of the underpinning regulatory mechanisms [10, 19, 37, 51-54]. It is widely implied that oncogenes reprogram metabolism to sustain cell growth, whereas tumor suppressors halt malignancy also by mean of metabolic regulation [19, 55, 56]. This network assumes a striking relevance in the case of p53, as impairing p53 family ability to trigger apoptosis [57-64], senescence [65-73] and cell-cycle arrest does not abolish its tumor suppressor efficacy [74-78], which apparently is maintained through regulation of metabolic genes[50, 79-83]. This suggests that metabolism might have greater relevance than previously thought in repressing cellular transformation.

Figure 3. Metabolic Analysis of TAp73 KO mouse Cortex and Hippocampus.

Nucleotide metabolism in TAp73 knockout (TA73KO) versus wild-type (WT) mouse cerebral cortex (C) and hippocampus (H) (n=8 biological littermate replicates; age 1 day). These are the two areas of the central nervous system that show developmental defects in the knockout mice. (a) adenosine 5′-monophosphate (AMP), (b) guanosine 5′-monophosphate (5′-GMP). Box indicates upper/lower quartile, bars max/min of distribution. * p<0.05.

TAp73 has been known as a tumor suppressor gene able to induce cell cycle arrest and apoptosis [30, 84] similarly to its sibling p53 [40, 85-91]. This view has been recently challenged by the finding that TAp73 promotes cellular proliferation through the expression of the PPP enzyme G6PD and, therefore, diverts glucose metabolism towards PPP and production of NADPH for ROS detoxification and ribose for nucleotide biosynthesis and proliferation [35]. In the attempt to unravel the link between TAp73 and regulation of cellular metabolism, and to understand its association with the established tumor suppressor role of TAp73, we have performed metabolic analysis in-vitro, in cells overexpressing TAp73β and in-vivo in mice depleted of TAp73. We did not observe evident differences in PPP, but we did record increase glycolytic rate in TAp73 expressing Saos-2 cells, together with augmented uptake of amino acids and increased biosynthesis of acetyl-CoA (manuscript in preparation). Moreover we observed a robust increased in intracellular content of nucleotides. Altered metabolism of nucleotides was also identified in in the cortex and hippocampus of TAp73 depleted mice, underlining the physiological relevance of TAp73-mediated control of metabolism. These data are partially in agreement with the findings of Du and colleagues [35]. But the interpretation that TAp73 promotes proliferation [35] would represent a paradigm shift for the p53 family [40, 85, 92] and would hardly reconcile with the ability of TAp73 to regulate expression of the cell cycle inhibitor p21 and to induce apoptosis. Indeed, our data and work from other groups have consistently demonstrated that TAp73 does halt cell cycle and induce cell death in a variety of cells and in response to diverse stimuli, acting as a proper tumor suppressor [24, 29, 43, 85, 92]. Therefore, we question whether the experimental data are sufficiently robust to support this change of dogma.

On the other hand, we have recently demonstrated that TAp73 knockout mice are affected by an aging phenotype accompanied by decreased mitochondrial function, augmented intracellular ROS levels and sensitivity to oxidative stress [31]. These metabolic alterations ultimately converge in promoting accelerated senescence in vitro and aging in-vivo. Therefore, the regulation of cellular metabolism by TAp73 could be interpreted on the light of its anti-senescence and anti-ageing function. This interpretation is reinforced by the finding that cellular senescence suppresses nucleotide metabolism [93, 94]. We could therefore envisage a scenario where TAp73 expression leads to cell cycle arrest or cell death, but promotes a metabolic rewiring that prevents normal cell from undergoing senescence, with possible important implication for neuronal development and neurodegenerative disease, on the light of TAp73 involvement in brain physiology [38, 95].

In summary, our interpretation of the apparent inconsistency, whereby TAp73 promotes “biochemical proliferation” and “cellular cell death”, inhibiting tumor progression, is that TAp73 counteracts cellular senescence by activating an anti-senescence metabolic response.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells culture

SaOs-2 Tet-On inducible for TAp73 were cultured at 37 °C in 5% CO2 in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco), supplemented with 10% FCS, 250 mM L-glutamine, penicillin/streptomycin (1 U/ml), and 1 mM pyruvate (all from Life Technologies). TAp73 expression was induced by addition of doxycycline (Sigma) 2μg/ml (stock 2mg/ml in PBS) for the indicated time.

Western Blots

Proteins were extracted from cell pellets using RIPA buffer (25mM Tris/HCl pH 7.6, 150mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) supplemented with phosphatase and protease inhibitor cocktails (ROCHE). Quantification of protein extracts was performed using BCA protein assay from PIERCE. 40μg of protein were boiled for 6 minutes at 90°C and then separated using SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes using standard transfer techniques and blocked with 5% milk for 2h at room temperature. Primary antibodies were incubated O/N at 4°C in blocking with gentle agitation. We used rabbit HA (Santa Cruz, Y11), rabbit β-tubulin (Santa Cruz, H-135), rabbit p21 (H-164) and Alexis anti-PARP. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (BioRad) and ECL chemoluminescence substrate (PIERCE) were used for final detection.

Metabolic analysis

TAp73 SaOs-2 Tet-On cell lines were cultured in growing medium and treated for 8h and 16h with doxycycline 2 μg/ml to induce TAp73β expression. Control cells were treated with vehicle (PBS) for 16h. Thirty million cells were spun down and pellets were washed once with cold PBS before being frozen in dry ice. All the samples were extracted using standard metabolic solvent extraction methods and analyzed through GC/MS and LS/MS as previously described [44]. After log transformation and imputation with minimum observed values for each group, the comparison of the metabolic compounds of the indicated samples was visualized.

Cell cycle and survival

For cell cycle analysis 500,000 cells were treated for the indicated time with doxycycline 2μg/ml, collected and fixed with ice cold 70% ethanol. After O/N fixing at −20°C, cells were washed in PBS, resuspended in 50μl of 10μg/ml RNase solution (SIGMA) and incubated for 10 minutes at 37°C. 500μl of staining solution (50μg/ml propidium iodide in PBS) was added to the cells, followed by additional incubation 30 minutes at 37°C. Stained cells were analyzed by flow cytometry and at least 10,000 cells per sample were collected. Data were analyzed using CELLQuest acquisition/analysis software.

Mice

TAp73 null mice in C57BL6 background were genotyped as previously described [24]. For metabolic analysis cortex and hippocampus were removed from 1 day old mice of both genotype and immediately frozen and stored at −80° C.

The animal experiments were performed under project licenses PPL 40/3442, granted to MA by the UK Home Office. Animal husbandry and experimental design met the standards required by the UKCCCR guidelines.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff members of the animal facility at University of Leicester. We thank Dr Ivano Amelio for scientific discussion. This study was supported by the Medical Research Council, United Kingdom, by MIUR, MinSan/IDI-IRCCS (RF73, RF57), by the Italian Association for Cancer Research (AIRC) investigator grants awarded to G.M.

Abbreviations

- GC

Gas chromatography

- MS

Mass Spectrometry

- LC

Liquid chromatography

- DMED

Dulbecco minimal essential medium

- FBS

foetal bovine serum

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests

REFERENCES

- 1.Schulze A, Harris AL. How cancer metabolism is tuned for proliferation and vulnerable to disruption. Nature. 2012;491:364–373. doi: 10.1038/nature11706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Markert EK, Levine AJ, Vazquez A. Proliferation and tissue remodeling in cancer: the hallmarks revisited. Cell death & disease. 2012;3:e397. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2012.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao Y, Butler EB, Tan M. Targeting cellular metabolism to improve cancer therapeutics. Cell death & disease. 2013;4:e532. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sotgia F, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Lisanti MP. Cancer metabolism: new validated targets for drug discovery. Oncotarget. 2013;4:1309–1316. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garufi A, Ricci A, Trisciuoglio D, Iorio E, Carpinelli G, Pistritto G, Cirone M, D'Orazi G. Glucose restriction induces cell death in parental but not in homeodomain-interacting protein kinase 2-depleted RKO colon cancer cells: molecular mechanisms and implications for tumor therapy. Cell death & disease. 2013;4:e639. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Selvarajah J, Nathawat K, Moumen A, Ashcroft M, Carroll VA. Chemotherapy-mediated p53-dependent DNA damage response in clear cell renal cell carcinoma: role of the mTORC1/2 and hypoxia-inducible factor pathways. Cell death & disease. 2013;4:e865. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hill R, Rabb M, Madureira PA, Clements D, Gujar SA, Waisman DM, Giacomantonio CA, Lee PW. Gemcitabine-mediated tumour regression and p53-dependent gene expression: implications for colon and pancreatic cancer therapy. Cell death & disease. 2013;4:e791. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Favaro E, Harris AL. Targeting glycogen metabolism: a novel strategy to inhibit cancer cell growth? Oncotarget. 2013;4:3–4. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cairns RA, Harris IS, Mak TW. Regulation of cancer cell metabolism. Nature reviews Cancer. 2011;11:85–95. doi: 10.1038/nrc2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cook CC, Kim A, Terao S, Gotoh A, Higuchi M. Consumption of oxygen: a mitochondrial-generated progression signal of advanced cancer. Cell death & disease. 2012;3:e258. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2011.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gorrini C, Harris IS, Mak TW. Modulation of oxidative stress as an anticancer strategy. Nature reviews Drug discovery. 2013;12:931–947. doi: 10.1038/nrd4002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Munoz-Pinedo C, El Mjiyad N, Ricci JE. Cancer metabolism: current perspectives and future directions. Cell death & disease. 2012;3:e248. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2011.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kroemer G, Pouyssegur J. Tumor cell metabolism: cancer's Achilles' heel. Cancer cell. 2008;13:472–482. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wahdan-Alaswad R, Fan Z, Edgerton SM, Liu B, Deng XS, Arnadottir SS, Richer JK, Anderson SM, Thor AD. Glucose promotes breast cancer aggression and reduces metformin efficacy. Cell cycle. 2013;12:3759–3769. doi: 10.4161/cc.26641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang W, Lu Z. Nuclear PKM2 regulates the Warburg effect. Cell cycle. 2013;12:3154–3158. doi: 10.4161/cc.26182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Menendez JA, Joven J. One-carbon metabolism: an aging-cancer crossroad for the gerosuppressant metformin. Aging (Albany NY) 2012;4:894–898. doi: 10.18632/aging.100523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Laurenzi V, Melino G, Savini I, Annicchiarico-Petruzzelli M, Finazzi-Agro A, Avigliano L. Cell death by oxidative stress and ascorbic acid regeneration in human neuroectodermal cell lines. European journal of cancer. 1995;31A:463–466. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(95)00059-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levine AJ, Puzio-Kuter AM. The control of the metabolic switch in cancers by oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. Science. 2010;330:1340–1344. doi: 10.1126/science.1193494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang MY, Kim HB, Piao C, Lee KH, Hyun JW, Chang IY, You HJ. The critical role of catalase in prooxidant and antioxidant function of p53. Cell death and differentiation. 2013;20:117–129. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2012.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanchez-Macedo N, Feng J, Faubert B, Chang N, Elia A, Rushing EJ, Tsuchihara K, Bungard D, Berger SL, Jones RG, Mak TW, Zaugg K. Depletion of the novel p53-target gene carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1C delays tumor growth in the neurofibromatosis type I tumor model. Cell death and differentiation. 2013;20:659–668. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2012.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen JQ, Russo J. Dysregulation of glucose transport, glycolysis, TCA cycle and glutaminolysis by oncogenes and tumor suppressors in cancer cells. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2012;1826:370–384. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Evangelou K, Bartkova J, Kotsinas A, Pateras IS, Liontos M, Velimezi G, Kosar M, Liloglou T, Trougakos IP, Dyrskjot L, Andersen CL, Papaioannou M, Drosos Y, et al. The DNA damage checkpoint precedes activation of ARF in response to escalating oncogenic stress during tumorigenesis. Cell death and differentiation. 2013;20:1485–1497. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tomasini R, Tsuchihara K, Wilhelm M, Fujitani M, Rufini A, Cheung CC, Khan F, Itie-Youten A, Wakeham A, Tsao MS, Iovanna JL, Squire J, Jurisica I, et al. TAp73 knockout shows genomic instability with infertility and tumor suppressor functions. Genes & development. 2008;22:2677–2691. doi: 10.1101/gad.1695308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosenbluth JM, Pietenpol JA. The jury is in: p73 is a tumor suppressor after all. Genes & development. 2008;22:2591–2595. doi: 10.1101/gad.1727408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Candi E, Agostini M, Melino G, Bernassola F. How the TP53 family proteins TP63 and TP73 contribute to tumorigenesis: regulators and effectors. Human mutation. 2014;35:702–714. doi: 10.1002/humu.22523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Conforti F, Sayan AE, Sreekumar R, Sayan BS. Regulation of p73 activity by post-translational modifications. Cell death & disease. 2012;3:e285. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2012.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Allocati N, Di Ilio C, De Laurenzi V. p63/p73 in the control of cell cycle and cell death. Experimental cell research. 2012;318:1285–1290. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tomasini R, Tsuchihara K, Tsuda C, Lau SK, Wilhelm M, Ruffini A, Tsao MS, Iovanna JL, Jurisicova A, Melino G, Mak TW. TAp73 regulates the spindle assembly checkpoint by modulating BubR1 activity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:797–802. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812096106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu T, Roh SE, Woo JA, Ryu H, Kang DE. Cooperative role of RanBP9 and P73 in mitochondria-mediated apoptosis. Cell death & disease. 2013;4:e476. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2012.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rufini A, Niklison-Chirou MV, Inoue S, Tomasini R, Harris IS, Marino A, Federici M, Dinsdale D, Knight RA, Melino G, Mak TW. TAp73 depletion accelerates aging through metabolic dysregulation. Genes & development. 2012;26:2009–2014. doi: 10.1101/gad.197640.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Amelio I, Markert EK, Rufini A, Antonov AV, Sayan BS, Tucci P, Agostini M, Mineo TC, Levine AJ, Melino G. p73 regulates serine biosynthesis in cancer. Oncogene. 2013 doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Possemato R, Marks KM, Shaul YD, Pacold ME, Kim D, Birsoy K, Sethumadhavan S, Woo HK, Jang HG, Jha AK, Chen WW, Barrett FG, Stransky N, et al. Functional genomics reveal that the serine synthesis pathway is essential in breast cancer. Nature. 2011;476:346–350. doi: 10.1038/nature10350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Locasale JW, Grassian AR, Melman T, Lyssiotis CA, Mattaini KR, Bass AJ, Heffron G, Metallo CM, Muranen T, Sharfi H, Sasaki AT, Anastasiou D, Mullarky E, et al. Phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase diverts glycolytic flux and contributes to oncogenesis. Nature genetics. 2011;43:869–874. doi: 10.1038/ng.890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Du W, Jiang P, Mancuso A, Stonestrom A, Brewer MD, Minn AJ, Mak TW, Wu M, Yang X. TAp73 enhances the pentose phosphate pathway and supports cell proliferation. Nature cell biology. 2013;15:991–1000. doi: 10.1038/ncb2789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiang P, Du W, Yang X. A critical role of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase in TAp73-mediated cell proliferation. Cell cycle. 2013;12:3720–3726. doi: 10.4161/cc.27267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tedeschi PM, Markert EK, Gounder M, Lin H, Dvorzhinski D, Dolfi SC, Chan LL, Qiu J, DiPaola RS, Hirshfield KM, Boros LG, Bertino JR, Oltvai ZN, et al. Contribution of serine, folate and glycine metabolism to the ATP, NADPH and purine requirements of cancer cells. Cell death & disease. 2013;4:e877. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Killick R, Niklison-Chirou M, Tomasini R, Bano D, Rufini A, Grespi F, Velletri T, Tucci P, Sayan BS, Conforti F, Gallagher E, Nicotera P, Mak TW, et al. p73: a multifunctional protein in neurobiology. Molecular neurobiology. 2011;43:139–146. doi: 10.1007/s12035-011-8172-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Inoue S, Tomasini R, Rufini A, Elia AJ, Agostini M, Amelio I, Cescon D, Dinsdale D, Zhou L, Harris IS, Lac S, Silvester J, Li WY, et al. TAp73 is required for spermatogenesis and the maintenance of male fertility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:1843–1848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323416111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Levine AJ, Tomasini R, McKeon FD, Mak TW, Melino G. The p53 family: guardians of maternal reproduction. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2011;12:259–265. doi: 10.1038/nrm3086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grespi F, Melino G. P73 and age-related diseases: is there any link with Parkinson Disease? Aging. 2012;4:923–931. doi: 10.18632/aging.100515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Flores ER, Lozano G. The p53 family grows old. Genes & development. 2012;26:1997–2000. doi: 10.1101/gad.202648.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Melino G, Bernassola F, Ranalli M, Yee K, Zong WX, Corazzari M, Knight RA, Green DR, Thompson C, Vousden KH. p73 Induces apoptosis via PUMA transactivation and Bax mitochondrial translocation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:8076–8083. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307469200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tucci P, Porta G, Agostini M, Dinsdale D, Iavicoli I, Cain K, Finazzi-Agro A, Melino G, Willis A. Metabolic effects of TiO2 nanoparticles, a common component of sunscreens and cosmetics, on human keratinocytes. Cell death & disease. 2013;4:e549. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.He Z, Liu H, Agostini M, Yousefi S, Perren A, Tschan MP, Mak TW, Melino G, Simon HU. p73 regulates autophagy and hepatocellular lipid metabolism through a transcriptional activation of the ATG5 gene. Cell death and differentiation. 2013;20:1415–1424. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ramadan S, Terrinoni A, Catani MV, Sayan AE, Knight RA, Mueller M, Krammer PH, Melino G, Ci E. p73 induces apoptosis by different mechanisms. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2005;331:713–717. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.03.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Agostini M, Tucci P, Chen H, Knight RA, Bano D, Nicotera P, McKeon F, Melino G. p73 regulates maintenance of neural stem cell. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2010;403:13–17. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.10.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Agostini M, Tucci P, Killick R, Candi E, Sayan BS, Rivetti di Val Cervo P, Nicotera P, McKeon F, Knight RA, Mak TW, Melino G. Neuronal differentiation by TAp73 is mediated by microRNA-34a regulation of synaptic protein targets. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:21093–21098. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112061109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Niklison-Chirou MV, Steinert JR, Agostini M, Knight RA, Dinsdale D, Cattaneo A, Mak TW, Melino G. TAp73 knockout mice show morphological and functional nervous system defects associated with loss of p75 neurotrophin receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:18952–18957. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221172110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li T, Kon N, Jiang L, Tan M, Ludwig T, Zhao Y, Baer R, Gu W. Tumor suppression in the absence of p53-mediated cell-cycle arrest, apoptosis, and senescence. Cell. 2012;149:1269–1283. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Noto A, Raffa S, De Vitis C, Roscilli G, Malpicci D, Coluccia P, Di Napoli A, Ricci A, Giovagnoli MR, Aurisicchio L, Torrisi MR, Ciliberto G, Mancini R. Stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 is a key factor for lung cancer-initiating cells. Cell death & disease. 2013;4:e947. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu SY, Zheng PS. High aldehyde dehydrogenase activity identifies cancer stem cells in human cervical cancer. Oncotarget. 2013;4:2462–2475. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Patra KC, Hay N. Hexokinase 2 as oncotarget. Oncotarget. 2013;4:1862–1863. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Patra KC, Wang Q, Bhaskar PT, Miller L, Wang Z, Wheaton W, Chandel N, Laakso M, Muller WJ, Allen EL, Jha AK, Smolen GA, Clasquin MF, et al. Hexokinase 2 is required for tumor initiation and maintenance and its systemic deletion is therapeutic in mouse models of cancer. Cancer cell. 2013;24:213–228. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vivanco I. Targeting molecular addictions in cancer. British journal of cancer. 2014 doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Montero J, Dutta C, van Bodegom D, Weinstock D, Letai A. p53 regulates a non-apoptotic death induced by ROS. Cell death and differentiation. 2013;20:1465–1474. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sorrentino G, Mioni M, Giorgi C, Ruggeri N, Pinton P, Moll U, Mantovani F, Del Sal G. The prolyl-isomerase Pin1 activates the mitochondrial death program of p53. Cell death and differentiation. 2013;20:198–208. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2012.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Valentino T, Palmieri D, Vitiello M, Pierantoni GM, Fusco A, Fedele M. PATZ1 interacts with p53 and regulates expression of p53-target genes enhancing apoptosis or cell survival based on the cellular context. Cell death & disease. 2013;4:e963. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hutt K, Kerr JB, Scott CL, Findlay JK, Strasser A. How to best preserve oocytes in female cancer patients exposed to DNA damage inducing therapeutics. Cell death and differentiation. 2013;20:967–968. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim SY, Cordeiro MH, Serna VA, Ebbert K, Butler LM, Sinha S, Mills AA, Woodruff TK, Kurita T. Rescue of platinum-damaged oocytes from programmed cell death through inactivation of the p53 family signaling network. Cell death and differentiation. 2013;20:987–997. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fan YH, Cheng J, Vasudevan SA, Dou J, Zhang H, Patel RH, Ma IT, Rojas Y, Zhao Y, Yu Y, Zhang H, Shohet JM, Nuchtern JG, et al. USP7 inhibitor P22077 inhibits neuroblastoma growth via inducing p53-mediated apoptosis. Cell death & disease. 2013;4:e867. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ali A, Bluteau O, Messaoudi K, Palazzo A, Boukour S, Lordier L, Lecluse Y, Rameau P, Kraus-Berthier L, Jacquet-Bescond A, Lelievre H, Depil S, Dessen P, et al. Thrombocytopenia induced by the histone deacetylase inhibitor abexinostat involves p53-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Cell death & disease. 2013;4:e738. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Candi E, Rufini A, Terrinoni A, Giamboi-Miraglia A, Lena AM, Mantovani R, Knight R, Melino G. DeltaNp63 regulates thymic development through enhanced expression of FgfR2 and Jag2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:11999–12004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703458104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sayan BS, Sayan AE, Knight RA, Melino G, Cohen GM. p53 is cleaved by caspases generating fragments localizing to mitochondria. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281:13566–13573. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512467200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fausti F, Di Agostino S, Cioce M, Bielli P, Sette C, Pandolfi PP, Oren M, Sudol M, Strano S, Blandino G. ATM kinase enables the functional axis of YAP, PML and p53 to ameliorate loss of Werner protein-mediated oncogenic senescence. Cell death and differentiation. 2013;20:1498–1509. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Iannetti A, Ledoux AC, Tudhope SJ, Sellier H, Zhao B, Mowla S, Moore A, Hummerich H, Gewurz BE, Cockell SJ, Jat PS, Willmore E, Perkins ND. Regulation of p53 and Rb Links the Alternative NF-kappaB Pathway to EZH2 Expression and Cell Senescence. PLoS genetics. 2014;10:e1004642. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Qian Y, Chen X. Senescence regulation by the p53 protein family. Methods in molecular biology. 2013;965:37–61. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-239-1_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Paris M, Rouleau M, Puceat M, Aberdam D. Regulation of skin aging and heart development by TAp63. Cell death and differentiation. 2012;19:186–193. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Burnley P, Rahman M, Wang H, Zhang Z, Sun X, Zhuge Q, Su DM. Role of the p63-FoxN1 regulatory axis in thymic epithelial cell homeostasis during aging. Cell death & disease. 2013;4:e932. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Richardson RB. p53 mutations associated with aging-related rise in cancer incidence rates. Cell cycle. 2013;12:2468–2478. doi: 10.4161/cc.25494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lin SC, Taatjes DJ. DeltaNp53 and aging. Aging (Albany NY) 2013;5:717–718. doi: 10.18632/aging.100609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Migliaccio E, Giorgio M, Pelicci PG. p53 and aging: role of p66Shc. Aging. 2013;5:488–489. doi: 10.18632/aging.100583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.McCubrey JA, Demidenko ZN. Recent discoveries in the cycling, growing and aging of the p53 field. Aging (Albany NY) 2012;4:887–893. doi: 10.18632/aging.100529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Brady CA, Jiang D, Mello SS, Johnson TM, Jarvis LA, Kozak MM, Kenzelmann Broz D, Basak S, Park EJ, McLaughlin ME, Karnezis AN, Attardi LD. Distinct p53 transcriptional programs dictate acute DNA-damage responses and tumor suppression. Cell. 2011;145:571–583. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hanel W, Marchenko N, Xu S, Yu SX, Weng W, Moll U. Two hot spot mutant p53 mouse models display differential gain of function in tumorigenesis. Cell death and differentiation. 2013;20:898–909. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jiang D, Brady CA, Johnson TM, Lee EY, Park EJ, Scott MP, Attardi LD. Full p53 transcriptional activation potential is dispensable for tumor suppression in diverse lineages. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:17123–17128. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111245108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mello SS, Attardi LD. Not all p53 gain-of-function mutants are created equal. Cell death and differentiation. 2013;20:855–857. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Haupt S, Gamell C, Wolyniec K, Haupt Y. Interplay between p53 and VEGF: how to prevent the guardian from becoming a villain. Cell death and differentiation. 2013;20:852–854. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Grabow S, Waring P, Happo L, Cook M, Mason KD, Kelly PN, Strasser A. Pharmacological blockade of Bcl-2, Bcl-x(L) and Bcl-w by the BH3 mimetic ABT-737 has only minor impact on tumour development in p53-deficient mice. Cell death and differentiation. 2012;19:623–632. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Blagosklonny MV. Tumor suppression by p53 without apoptosis and senescence: conundrum or rapalog-like gerosuppression? Aging. 2012;4:450–455. doi: 10.18632/aging.100475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Peng X, Zhang MQ, Conserva F, Hosny G, Selivanova G, Bykov VJ, Arner ES, Wiman KG. APR-246/PRIMA-1MET inhibits thioredoxin reductase 1 and converts the enzyme to a dedicated NADPH oxidase. Cell death & disease. 2013;4:e881. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Guerrieri F, Piconese S, Lacoste C, Schinzari V, Testoni B, Valogne Y, Gerbal-Chaloin S, Samuel D, Brechot C, Faivre J, Levrero M. The sodium/iodide symporter NIS is a transcriptional target of the p53-family members in liver cancer cells. Cell death & disease. 2013;4:e807. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bergeaud M, Mathieu L, Guillaume A, Moll UM, Mignotte B, Le Floch N, Vayssiere JL, Rincheval V. Mitochondrial p53 mediates a transcription-independent regulation of cell respiration and interacts with the mitochondrial F(1)F0-ATP synthase. Cell cycle. 2013;12:2781–2793. doi: 10.4161/cc.25870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tomasini R, Mak TW, Melino G. The impact of p53 and p73 on aneuploidy and cancer. Trends in cell biology. 2008;18:244–252. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rufini A, Agostini M, Grespi F, Tomasini R, Sayan BS, Niklison-Chirou MV, Conforti F, Velletri T, Mastino A, Mak TW, Melino G, Knight RA. p73 in Cancer. Genes & cancer. 2011;2:491–502. doi: 10.1177/1947601911408890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wiman KG. p53 talks to PARP: the increasing complexity of p53-induced cell death. Cell death and differentiation. 2013;20:1438–1439. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Carvajal LA, Manfredi JJ. Another fork in the road--life or death decisions by the tumour suppressor p53. EMBO reports. 2013;14:414–421. doi: 10.1038/embor.2013.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kracikova M, Akiri G, George A, Sachidanandam R, Aaronson SA. A threshold mechanism mediates p53 cell fate decision between growth arrest and apoptosis. Cell death and differentiation. 2013;20:576–588. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2012.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Neise D, Sohn D, Stefanski A, Goto H, Inagaki M, Wesselborg S, Budach W, Stuhler K, Janicke RU. The p90 ribosomal S6 kinase (RSK) inhibitor BI-D1870 prevents gamma irradiation-induced apoptosis and mediates senescence via RSK- and p53-independent accumulation of p21WAF1/CIP1. Cell death & disease. 2013;4:e859. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chillemi G, Davidovich P, D'Abramo M, Mametnabiev T, Garabadzhiu AV, Desideri A, Melino G. Molecular dynamics of the full-length p53 monomer. Cell cycle. 2013;12:3098–3108. doi: 10.4161/cc.26162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Marouco D, Garabadgiu AV, Melino G, Barlev NA. Lysine-specific modifications of p53: a matter of life and death? Oncotarget. 2013;4:1556–1571. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Melino G, De Laurenzi V, Vousden KH. p73: Friend or foe in tumorigenesis. Nature reviews Cancer. 2002;2:605–615. doi: 10.1038/nrc861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Aird KM, Zhang G, Li H, Tu Z, Bitler BG, Garipov A, Wu H, Wei Z, Wagner SN, Herlyn M, Zhang R. Suppression of nucleotide metabolism underlies the establishment and maintenance of oncogene-induced senescence. Cell reports. 2013;3:1252–1265. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Darzynkiewicz Z. Perturbation of nucleotide metabolism--the driving force of oncogene-induced senescence. Oncotarget. 2013;4:649–650. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Billon N, Terrinoni A, Jolicoeur C, McCarthy A, Richardson WD, Melino G, Raff M. Roles for p53 and p73 during oligodendrocyte development. Development. 2004;131:1211–1220. doi: 10.1242/dev.01035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]