Abstract

A perianal tick and the surrounding skin were surgically excised from a 73-year-old man residing in a southwestern costal area of the Korean Peninsula. Microscopically a deep penetrating lesion was formed beneath the attachment site. Dense and mixed inflammatory cell infiltrations occurred in the dermis and subcutaneous tissues around the feeding lesion. Amorphous eosinophilic cement was abundant in the center of the lesion. The tick had Y-shaped anal groove, long mouthparts, ornate scutum, comma-shaped spiracular plate, distinct eyes, and fastoons. It was morphologically identified as a fully engorged female Amblyomma testudinarium. This is the third human case of Amblyomma tick infection in Korea.

Keywords: Amblyomma testudinarium, tick, human, histopathology

INTRODUCTION

The ticks that belong to the genus Amblyomma are large, ornate, longirostrate blood-feeding ectoparasites of a wide variety of vertebrates [1,2]. A lot of Amblyomma species have been recorded around the world [3]. Amblyomma testudinarium is one of the species that has been frequently reported to bite humans in Asian countries. A total of 108 patients were recorded in Japan between 1960 and 2005 [4]. Most of these cases occurred in southern areas of Japan. Usually, only a few ticks attached to and fed on a human, but 3 reported cases were infested with more than 100 larval ticks [5]. In Malaysia, a patient repeatedly infested with A. testudinarium was reported [6].

It is well known that A. testudinarium is distributed in Korea [7,8]. However, human infestation of A. testudinarium tick is rare, with 2 previously reported cases in elderly Korean persons [9,10]. We report here an additional case of perianal infestation with A. testudinarium and provide histopathologic observations of its attachment to the skin.

CASE RECORD

A 73-year-old Korean man with a round nodule in the left perianal area presented to our clinic in September 2010. The solitary nodule had been found about 2 weeks before admission and was not accompanied by hemorrhage and pain. Laboratory studies were normal or negative. The patient was a retired man and frequently went freshwater fishing. He recalled a trip to a water reservoir located at Yeonggwang-gun (between 35 to 36° North latitude), a rural county in Jeollanam-do Province, South Korea 1 month before the presentation. At that time, he defecated in the sitting posture on the grass near the water reservoir and felt the pain of sting around anus. He underwent appendectomy several years ago and was on hypertension medication.

On admission, the protruding mass was firmly attached to the perianal skin. Gross appearance of the tick bite site was characterized by a mild swelling and erythema. The patient agreed to surgical treatment of the skin lesion to remove the perianal tick. An excision biopsy was performed at the site where the tick was attached. The tick and the surrounding skin tissue were removed carefully (Fig. 1A), placed in 10% buffered formalin and submitted for evaluation. During histologic processing, the tick was accidentally separated from the biopsied skin tissue.

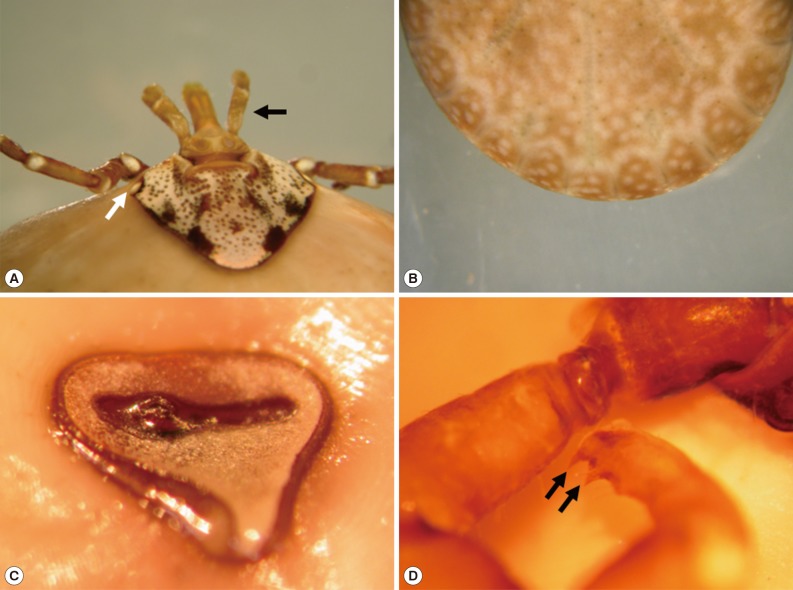

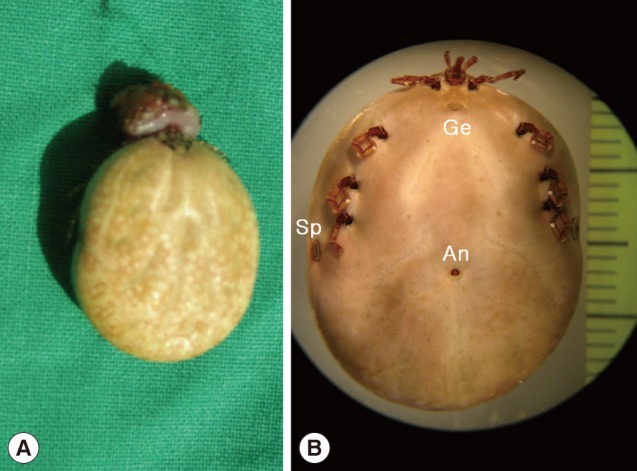

Fig. 1.

The engorged female tick, Amblyomma testudinarium, removed from a Korean man. (A) Gross photograph of the tick and skin tissue biopsied from the attachment site. (B) Stereoscopic photograph of the formalin-fixed tick. The body is 25×18 mm in size and widest in the region of the spiracular plate. It has 4 pairs of legs. The spiracular plates (Sp) are located on the ventrolateral surface posterolaterally to the coxa IV. The genital aperture (Ge) is located at the level between the coxa I and coxa II. The anus (An) is located at the level posterior to the spiracular plates and embraced by Y-shaped anal groove posteriorly.

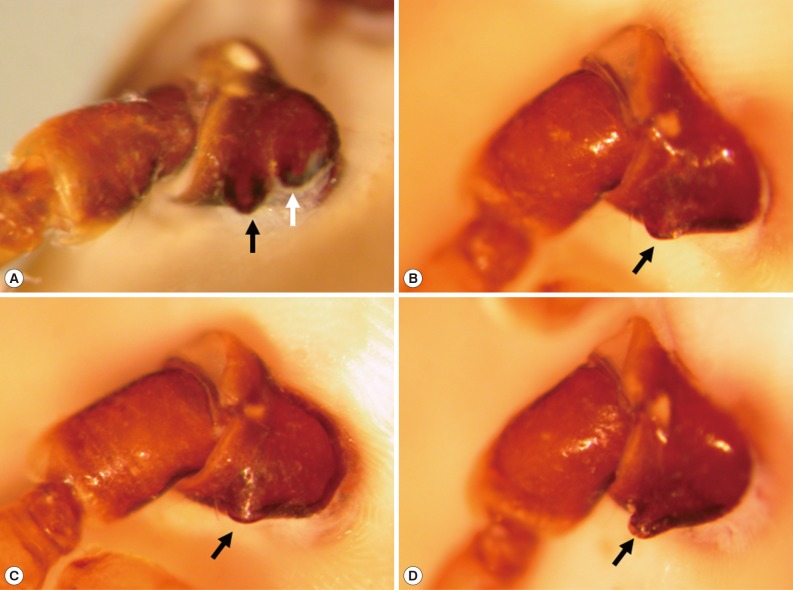

The fixed tick was examined stereoscopically. It was 25 mm in length and 18 mm in width and engorged with blood meal (Fig. 1B). The mouthparts were preserved well (Fig. 2A). The basis capituli was dorsally subrectangular, and its maximum width was 1.8 mm. The pedipalps had a long article II with approximately 2.5 times as long as the article III. The hypostome was 1.8 mm in length and had 4/4 dentition. The denticles of the inner file were much smaller than those of the other files. The ornamented scutum was relatively small, and its punctuations were dark brown or brownish-black spots on a pale yellow background (Fig. 2A). The eyes were located on the lateral edges of the scutum but not projecting (Fig. 2A). Eleven rectangular divisions called festoons were present on the rear body edge (Fig. 2B). The spiracular plate was comma-shaped (Fig. 2C) and located on the ventrolateral surface posterolaterally to the coxa IV (Fig. 1B). The genital aperture was located at the level between the coxa I and coxa II (Fig. 1B). The anus was located at the level posterior to the spiracular plates and embraced by Y-shaped anal groove posteriorly (Fig. 1B). The tick had 4 pairs of legs. The coxa I had 2 subequal spurs, and the external spur was slightly longer than the internal spur (Fig. 3A). The coxae II and III had a single salient ridge-like spur (Fig. 3B, C). The coxa IV had a single spur which was longer than those of the coxae II and III (Fig. 3D). The tarsi III and IV had 2 subapical ventral spurs (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

External organs of the removed tick, Amblyomma testudinarium. (A) The scutum shows splendid ornamentations with irregular dark brown or brownish-black spots on a pale yellow background. The eyes (white arrow) are located on the lateral edges of the scutum but not projecting beyond the scutal contour. The pedipalps (black arrow) are slender and not salient laterally. Their article II is approximately 2.5 times longer than the article III. (B) The festoons are present on the rear body edge and composed of 11 rectangular divisions. (C) The spiracular plate is comma-shaped. (D) The tarsus III has 2 subapical ventral spurs (arrow).

Fig. 3.

The coxae of the removed tick, Amblyomma testudinarium. (A) The coxa I has 2 medium-sized subequal spurs. The external spur (black arrow) is slightly longer than the internal one (white arrow). (B) The coxa II has a single salient ridge-like spur (arrow) which is broader than long. (C) The coxa III shows a single spur (arrow) which is very similar to that of coxa II. (D) The coxa IV has a single spur (arrow) that is longer than those of coxae II and III.

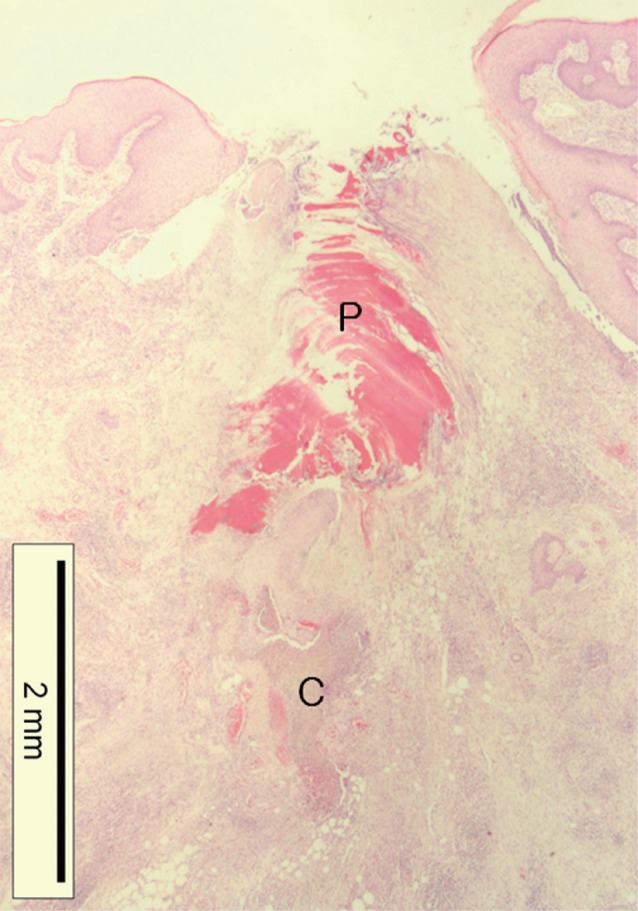

The skin sections were made and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Microscopical examinations revealed an intense skin reaction at the site where the tick had attached. Due to deep penetration, the pathological changes were observed through all skin layers from the epidermis to the subcutaneous fat layer. In a low power field, the lesion comprised of central amorphous eosinophilic material and surrounding inflammatory cell infiltrations (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Histopathological changes of the tick-feeding lesion; epidermal laceration and invagination, dermal cavitary (C) and perirostral (P) lesion containing abundant amorphous eosinophilic material, and dense inflammatory cell infiltrations around the penetrating site in the dermis and subcutaneous fat tissue (H&E stain, ×12.5).

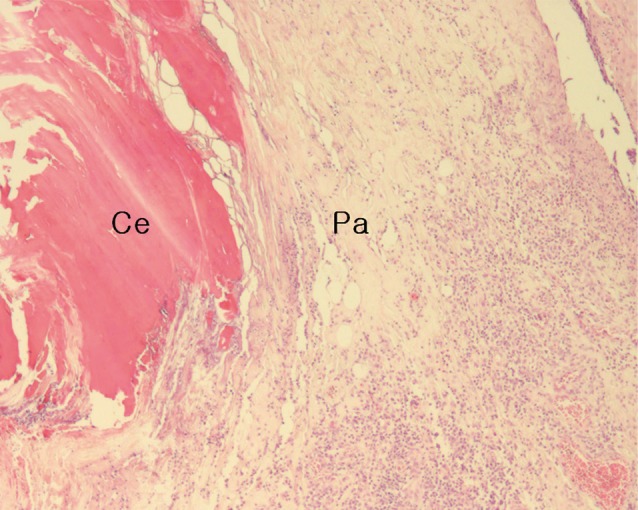

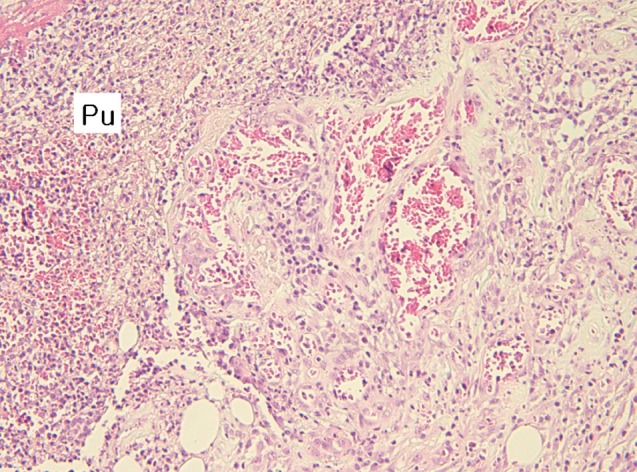

At the site of the tick bite, a small epidermal defect and invaginated squamous epithelium were seen. The epidermal defect was about 1.8 mm in width and adjacent epidermis revealed parakeratosis, hyperkeratosis, and mild spongiosis. Scattered inflammatory cells, mainly neutrophils, were seen in the epidermis. In the dermis, a characteristic feeding lesion was formed immediately beneath the attachment site. It was composed of 2 different portions; superficial perirostral portion and deep cavitary portion (Fig. 4). The perirostral portion was 2.1 mm in depth and much wider at the distal part than at its entrance. It was abundantly filled with homogeneous eosinophilic material called cement. The cement, however, was found slightly at the dermal entrance of the tick mouthparts but not on the surface of the epidermis. It was lamellate and had projections into the adjacent tissue in some areas (Fig. 5). The cavitary portion was located under the perirostral lesion and surrounded by granulation tissues. It was relatively small and filled with purulent exudates containing inflammatory cells and erythrocytes (Fig. 6). A dense and mixed cellular infiltrate was also noted around the feeding lesion and extended into neighboring dermis and subcutaneous tissues. The cellular components were lymphocytes, neutrophils, histiocytes, and eosinophils. However, there were very few inflammatory cells immediately adjacent to the site which abutted the eosinophilic cement (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

The perirostral portion of the dermal tick-feeding lesion; a paucicellular (Pa) zone having relatively few inflammatory cells around the penetrating site abutting amorphous eosinophilic cement (Ce) (H&E stain, ×40).

Fig. 6.

The cavitary portion of the dermal tick-feeding lesion; suppurative inflammation characterized by large amounts of pus (Pu), granulation tissue showing vascular proliferation, and inflammatory cell infiltrations (H&E stain, ×100).

After excision, the use of systemic antimicrobials was recommended to prevent complication. There was no evidence of infection or residual disease up to 1 month after surgical removal of the tick.

DISCUSSION

Among the hard ticks, only 3 genera, Ixodes, Haemaphysalis, and Amblyomma have been recorded from humans in the Republic of Korea [9,10,11]. Gross morphological characteristics are very important in their identification. The present tick is large and has an anal groove contouring the anus posteriorly. This means that it does not belong to the genus Ixodes which is the most common cause of human tick-bites in Korea [11]. The pedipalps of the present specimen are slender and longer than the basis capituli, and their second segment is not salient laterally. The eyes and fastoons are present, the small scutum is ornate, and the spiracular plate is comma-shaped. Therefore, it belongs to the genus Amblyomma [2,7]. In the hypostome, the denticles of the inner file are much smaller than those of the other files. The external spur of the coxa I is slightly longer than the internal one. The spur of the coxa IV is longer than those of coxae II and III. The tarsi III and IV have 2 distinct subapical ventral spurs. From the above observations, this tick is easily distinguished from Amblyomma nitidum and Amblyomma geoemydae which are distributed in the Far East Asia [2]. Therefore, our tick has been identified as a female adult of A. testudinarium based on morphological characteristics.

The warm temperature and subtropical vegetation fauna are known to be a proper environmental condition for A. testudinarium. Thus, this tick is more common in the tropic areas, including South East Asia and Indian Peninsula [2]. In Japan, the closest geographical neighbor to Korea, A. testudinarium is one of the most common ticks infesting humans and especially important in southwestern areas [4,12]. In Korea, it is also distributed in Jeju Island and the southern coastal area of the mainland [7,8]. The first human case was reported in Suncheon City (35° north latitude), a southern coastal area of Jeollanam-do [9]. The second case occurred in Tongyeong City (below 35° north latitude), southern coastal area of Gyeongsangnam-do [10]. In the present case, the patient was infested in Yeonggwang-gun, a western coastal area of Jeollanam-do. Therefore, A. testudinarium extends the geographic range of distribution from the southern coastal area more northwards to the southwestern costal area (below 36° north latitude) of the Korean Peninsula.

Hard ticks remain attached for days to weeks and engorged with blood. The great pathological responses by host occur as the result of feeding by ticks. Feeding is a complex process for hard ticks [13,14]. After a site for feeding has been chosen, ticks embed their anterior part calling capitulum into the skin. The capitulum is composed of 4 different components; the palps, chelicerae, hypostome, and basis capituli. Ticks attached on the skin lacerate the epidermal layers using the chelicerae which are paired appendages for cutting, ripping, and tearing skin. After epidermal laceration, ticks insert midline mouthparts (the chelicerae and hypostome) into the opening at a depth that varies by species. In the present case, the depth of penetration is similar to the length of the hypostome which has been deeply inserted into the dermis. However, the width of epidermal laceration is not similar to that of mouthparts but similar to that of the basis capituli. This means that the basis capituli is embedded shallowly in the host epidermis during the feeding period.

The histopathology of skin responses to infection with the present female A. testudinarium shows that the dermis is infiltrated with various inflammatory cells associated with both acute and chronic reactions, i.e., lymphocytes, neutrophils, histiocytes, and eosinophils. The intense and mixed infiltrates extend into the subcutaneous fat. These inflammatory findings are similar to those reported by other researchers on Amblyomma species experimentally and naturally infested in various vertebrate hosts [15,16,17]. Around the lesion abutting the cement, we observed an interesting area having relatively few inflammatory cells. This cell-free area is called the paucicellular zone. The biologic factors causing a zone of minimal cellular inflammation are not exactly known but are likely due to the anti-inflammatory effects of the tick saliva [18]. According to the study on the effects of tick saliva and salivary gland extracts [19], this paucicellular zone might reflect tick-induced suppression of cellular migration into the injury site as a result of saliva constituents suppressing the movement of cells into the feeding lesion.

The salivary glands of hard ticks secret eosinophilic cement material that help attachment of the tick to the host for the feeding period. It is well known that there is considerable difference in the distribution of the cement within the host tissue. Generally, ixodids with long mouthparts (longirostrate ticks) penetrate the skin deeply to the dermis and have a perirostal secretion of the cement. Ixodids with short mouthparts (brevirostrate ticks) have a copious superficial secretion of the cement which spreads over the skin [13,20]. Dermacentor, Haemaphysalis, Boophilus, and Rhipicephalus are classified as brevirostrate ticks. Amblyomma and Hyalomma are longirostrate ticks with relative long mouthparts [1]. In the present Amblyomma case, eosinophlic cement was found mostly in the perirostral portion but little on the skin surface.

Footnotes

We have no conflict of interest related to this work.

References

- 1.Kettle DS. Ixodida-Ixodidae (hard ticks) In: Kettle DS, editor. Medical and Veterinary Entomology. Slough, UK: CAB International; 1995. pp. 458–485. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yamaguti N, Tipton VJ, Keegan HL, Toshioka S. Ticks of Japan, Korea, and the Ryukyu Islands. Brigham Young Univ Sci Bull. 1971;15:1–226. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horak IG, Camicas JL, Keirans JE. The Argasidae, Ixodidae and Nuttalliellidae (Acari: Ixodida): a world list of valid tick names. Exp Appl Acarol. 2002;28:27–54. doi: 10.1023/a:1025381712339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Okino T, Ushirogawa H, Matoba K, Hatsushika R. Bibliographical studies on human cases of hard tick (Acarina: Ixodidae) bites in Japan (1) Cases of Amblyomma testudinarium infection. Kawasaki Med J. 2007;33:321–331. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Isohisa T, Nakai N, Okuzawa Y, Yamada M, Arizono N, Katoh N. Case of tick bite with infestation of an extraordinary number of larval Amblyomma testudinarium ticks. J Dermatol. 2011;38:1110–1112. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.01180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamauchi T, Takano A, Maruyama M, Kawabata H. Human Infestation by Amblyomma testudinarium (Acari: Ixodidae) in Malay Peninsula, Malaysia. J Acarol Soc Jpn. 2012;21:143–148. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kang YB, Suh MD, Kim YH, Byun SY, Lim HU. Amblyomma testudinarium Koch, 1844: discovery and record in Korea, and identification and redescription of male tick. Korean J Vet Res. 1981;21:65–72. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sames WJ, Kim HC, Chong ST, Lee IY, Apanaskevich DA, Robbins RG, Bast J, Moore R, Klein TA. Haemaphysalis (Ornithophysalis) phasiana (Acari: Ixodidae) in the Republic of Korea: two province records and habitat descriptions. Syst Appl Acarol. 2008;13:43–50. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim J, Joo HS, Moon HJ, Lee YJ. A case of Amblyomma testudinarium tick bite in a Korean woman. Korean J Parasitol. 2010;48:313–317. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2010.48.4.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suh KS, Park JB, Han SH, Lee IY, Cho BK, Kim ST, Jang MS. Tick bite on glans penis: the role of dermoscopy. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25:528–530. doi: 10.5021/ad.2013.25.4.528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang SH, Park JH, Kwak JE, Joo M, Kim H, Chi JG, Hong ST, Chai JY. A case of histologically diagnosed tick infestation on the scalp of a Korean child. Korean J Parasitol. 2006;44:157–161. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2006.44.2.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fournier PE, Fujita H, Takada N, Raoult D. Genetic identification of rickettsiae isolated from ticks in Japan. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:2176–2181. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.6.2176-2181.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arthur DR. Tick feeding and its implications. Adv Parasitol. 1970;8:275–292. doi: 10.1016/s0065-308x(08)60258-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGinley-Smith DE, Tsao SS. Dermatoses from ticks. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:363–392. doi: 10.1067/s0190-9622(03)01868-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown SJ, Knapp FW. Amblyomma americanum: sequential histological analysis of adult feeding sites on guinea pigs. Exp Parasitol. 1980;49:303–318. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(80)90067-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lima e Silva MF, Szabó MP, Bechara GH. Microscopic features of tick-bite lesions in anteaters and armadillos: Emas National Park and the Pantanal region of Brazil. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1026:235–241. doi: 10.1196/annals.1307.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van der Heijden KM, Szabó MP, Egami MI, Pereira MC, Matushima ER. Histopathology of tick-bite lesions in naturally infested capybaras (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris) in Brazil. Exp Appl Acarol. 2005;37:245–255. doi: 10.1007/s10493-005-4155-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krause PJ, Grant-Kels JM, Tahan SR, Dardick KR, Alarcon-Chaidez F, Bouchard K, Visini C, Deriso C, Foppa IM, Wikel S. Dermatologic changes induced by repeated Ixodes scapularis bites and implications for prevention of tick-borne infection. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2009;9:603–610. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2008.0091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kramer C, Nahmias Z, Norman DD, Mulvihill TA, Coons LB, Cole JA. Dermacentor variabilis: regulation of fibroblast migration by tick salivary gland extract and saliva. Exp Parasitol. 2008;119:391–397. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Binnington KC, Kemp DH. Role of tick salivary glands in feeding and disease transmission. Adv Parasitol. 1980;18:315–339. doi: 10.1016/s0065-308x(08)60403-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]