Abstract

Background & objectives:

New Delhi metallo β-lactamase-1 (NDM-1) producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates are potential threat to human health. This study was conducted to detect the presence of blaNDM-1 in carbapenem resistant P. aeruginosa in a tertiary care center in southern India.

Methods:

Sixty one carbapenem resistant clinical isolates of a total of 212 P. aeruginosa isolates cultured during the study period were screened for the presence of NDM-1by PCR. Clinical characteristics of the NDM-1 positive isolates were studied and outcome of the patients was followed up.

Results:

Of the 61 isolates, NDM-1 was detected in four isolates only. These were isolated from patients in the intensive care units and chest medicine ward. The source specimens were pus, sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage and endotracheal aspirate. The NDM-1 producers were susceptible only to polymyxin B. Only one patient responded to polymyxin B therapy, while the others succumbed to the infection.

Conclusion:

These findings reveal that NDM-1 is not a major mechanism mediating carbapenem resistance in P. aeruginosa in this centre. However, continuous surveillance and screening are necessary to prevent their dissemination.

Keywords: India, NDM-1, Pseudomonas aeruginosa

New Delhi metallo beta lactamase-1 (NDM-1), the recently discovered transferable molecular class B β-lactamase is a growing threat worldwide. First reported in 2008 in Sweden from a patient previously hospitalized in India, NDM-1- producing Enterobacteriaceae are now the focus of attention globally1,2,3. NDM-1- producing strains exhibit multidrug resistant profile because they harbour other genes that encode for resistance to aminoglycosides and fluoroquinolones4. Till date, reports of NDM-1 in Pseudomonas aeruginosa are scarce. There are only two reports of its occurrence in patients from Serbia and none of them had a history of travel to the Indian subcontinent5,6. Though reports are scarce and sporadic, knowledge of its prevalence is essential because P. aeruginosa is an environmental pathogen with intense colonization capacity and ability to persist for indefinite periods in the hospital environment7,8. NDM-1 has not been reported in P. aeruginosa from any other part of the world. In the present study, we report the presence of NDM-1 in carbapenem resistant P. aeruginosa clinical isolates in a university teaching hospital in south India.

Material & Methods

The study was conducted in the department of Microbiology, Sri Ramachandra Medical College and Research Institute, a 1600 bedded university teaching hospital in Chennai, South India, from April to October 2010. During this period, a total of 212 clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa were collected, of which 61 were carbapenem resistant. All of these were from patients hospitalized for 48 h or more. These were cultured from clinical specimens such as blood (8), urine (21), exudative specimens (11) such as pus, wound swabs, body fluids including cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and lower respiratory secretions (21) which included bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), endotracheal aspirates (ETA) and sputum. The organisms were identified upto species level using Microscan Walk Away 96, Gram-negative panels (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Inc – Sacramento CA, USA). Commensals were differentiated from pathogens for isolates obtained from non-sterile sites (respiratory tract, urinary tract and wound swabs) by ascertaining their significance based on clinical history, presence of the organism in the Gram stain, presence of intracellular forms of the organism and pure growth in culture with significant colony count. The isolates from sputum and endotracheal aspirates were further verified for their clinical significance by correlation with other respiratory parameters and findings in the chest radiograph. The clinical characteristics of the study patients were noted from records and follow up was done till discharge /death.

The study protocol was approved by the institutional ethics committee.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing: Susceptibility to various classes of antimicrobial agents was determined by disc diffusion method in accordance with Clinical Laboratory Standard Institute (CLSI) guidelines9. The antibiotics tested were amikacin (30 μg), ciprofloxacin (5 μg), ceftazidime (30 μg), aztreonam (30 μg), piperacillin-tazobactam (100/10 μg), imipenem (10 μg), meropenem (10 μg), colistin (10 μg) and polymyxin B (300 units) (Hi-media Laboratories, Mumbai, India).

Determination of minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC): Minimum inhibitory concentrations of imipenem and meropenem were determined by agar dilution method using cation adjusted Mueller Hinton Agar (MHA) (Hi-media Laboratories, India). Pure forms of imipenem and meropenem (Sigma Aldrich, India) were used. The scheme for preparing dilutions of antimicrobial agents and the methodology was according to CLSI guidelines9.

Phenotypic tests: Carbapenemase production was screened by the Modified Hodge test (MHT) and MBL production by inhibitor potentiated disk diffusion test with ethylene diamine tetra acetic acid (EDTA)10. Though CLSI does not advocate the use of MHT for the detection of carbapenemases production in P. aeruginosa, several investigators have found this test using meropenem as a useful screening test10,11. For the isolates which were negative on initial testing by the above method, the test was repeated on Mueller-Hinton agar supplemented with zinc sulphate at a concentration of 70 mg/l11.

Polymerase chain reaction PCR): All study isolates were subjected to PCR using primers targeting blaNDM-11,12,13. Co-existence of other MBL encoding genes namely bla VIM and blaIMP were looked for using consensus primer14. The primers used in the study are listed in Table I. For optimization of PCR, strains previously confirmed by PCR and gene sequencing were used as positive control and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 was used as negative control. All isolates were subjected to multiplex PCR for the detection of MBL genes: VIM, IMP, GIM, SIM and SPM15.

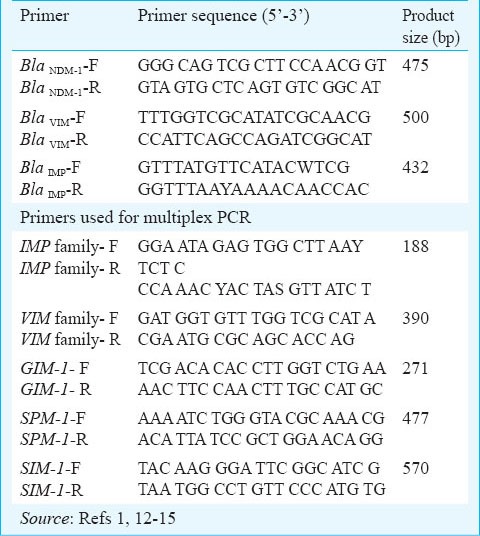

Table I.

Primers used in PCR and multiplex PCR for various genes in the study

DNA sequencing: PCR products of the isolates that carried the blaNDM-1 gene were purified using the PCR DNA purification kit (QIA quick Gel Extraction Kit, Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) and subjected to automated DNA sequencing (ABI 3100, Genetic Analyser, Applied Biosystems, USA). The aligned sequences were analyzed with the Bioedit sequence program and similarity searches for the nucleotide sequences were performed with the BLAST program (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

Results & Discussion

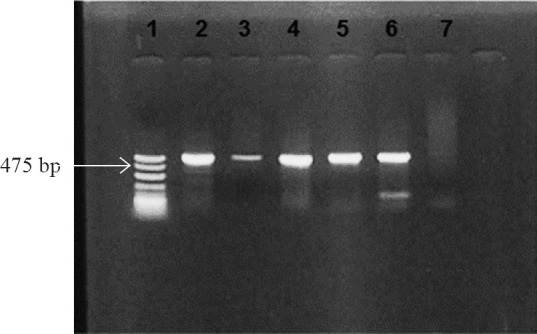

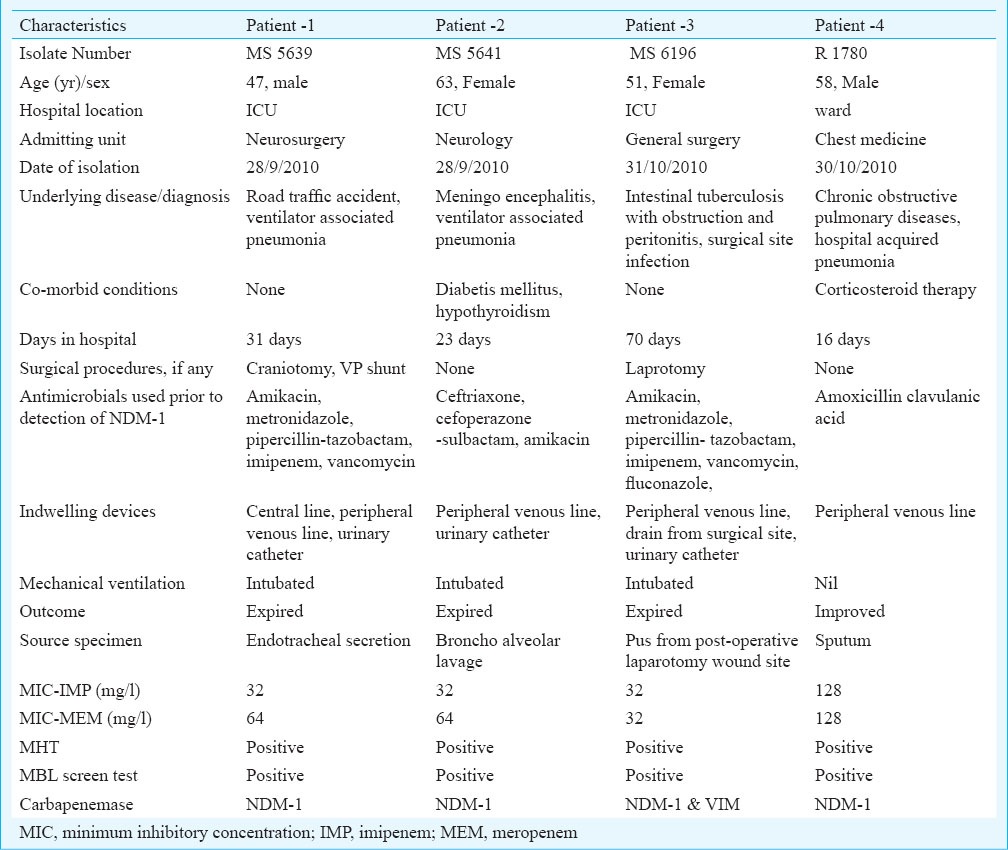

Of the 61 isolates tested, blaNDM-1 was found in four isolates only (MS 5639, MS 5641, MS 6196 and R 1780). The PCR screening results were validated by sequencing and the sequence of the blaNDM-1 genes showed 100 per cent identity with previously reported genes (Figure). These four NDM-1 positive P. aeruginosa were isolated from patients in multidisciplinary intensive care unit (2), neurosurgical intensive care unit (1) and chest medical ward (1). Both the phenotypic tests employed were positive in the NDM-1 producers. The source specimens were BAL, ETA, sputum and pus from post-operative laparotomy wound site. The isolate from pus also carried the blaVIM. blaNDM-1 was the only gene detected in the other three isolates. The NDM-1 producers were susceptible only to colistin and polymyxin B and resistant to amikacin, ciprofloxacin, aztreonam, piperacillin-tazobactam and ceftazidime. The clinical characteristics of the four patients are depicted in Table II.

Fig.

PCR for detection of blaNDM-1. Lane 1: molecular mass marker (100bp DNAladder); Lane 2: positive control; Lanes 3-6: blaNDM-1 positive isolates (amplicon size- 475bp); Lane 7: negative control.

Table II.

Clinical characteristics of the patients infected with NDM-1 producing P. aeruginosa

Overall, among the study isolates, blaNDM-1 alone was detected in three, blaNDM-1 coexisted with blaVIM in one isolate, blaVIM alone was detected in 33 isolates and two isolates carried the blaIMP gene alone. Further, blaSIM, blaSPM and blaGIM were not detected in any of the study isolates. In 22 isolates none of the genes looked for, were detected.

NDM-1 was first identified in Enterobacteriaceae and recently reported in Acinetobacter baumannii also. Variants of NDM-1 namely NDM-2 to NDM-7 differing in single aminoacid sequences have also been described7,14. Identification of blaNDM-1 in many genera and species of Gram-negative bacteria indicate that this gene can spread at a high rate2,17. The genes encoding NDM are heterogeneous on the basis of molecular size and location. In Enterobacteriaceae, it is plasmid-borne, while in A. baumannii both chromosomal and plasmid locations have been confirmed7,17. At the Military Medical Academy in Serbia, routine analysis of carbapenemase producing bacterial isolates revealed NDM-1 in seven clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa. The source patients were hospitalized in Serbia and had no history of travel to any other country5. Subsequently, in 2012 recurrent pyelonephritis due to NDM-1 producing P. aeruginosa was reported from France. This patient had history of prior hospitalization in Serbia and hence it was hypothesised that the Balkan States may be endemic for NDM-16.

This study was conducted to detect for the presence of blaNDM-1 in carbapenem resistant P. aeruginosa. Considering that of the 61 carbapenem resistant P. aeruginosa isolates tested, only four were found to harbour NDM-1, it can be reasonably assumed that NDM-1 is not a major mechanism mediating carbapenem resistance in P. aeruginosa in this hospital. This being a single centre report, further studies are required at national or regional levels to understand the magnitude and prevalence of NDM-1 in P. aeruginosa. Additionally, co-existence with other carbapenemase encoding genes was evident in a single isolate. On receipt of the microbiology culture report, all patients were initiated on polymyxin B therapy. While one patient responded, the others succumbed to the infection. The lone survivor was followed up till discharge after recovery. Of the previously reported Serbian patients infected with NDM-1 P. aeruginosa, two expired and the one with pyelonephritis recovered on treatment with colistin5,6.

None of the MBL encoding genes looked for were detected in 22 isolates. The possible operative mechanisms in these isolates may be hyperproduction of Amp C or other beta lactamases, porin defect and /or upregulation of efflux pumps8. In this study, however, the presence of these mechanisms was not evaluated.

The ability of NDM-1 producing P. aeruginosa to survive under a wide range of environmental conditions and potential to spread in hospital settings make them unique. Though not as prevalent as other MBLs such as IMP and VIM, strict vigilance and continuous surveillance of NDM-1 is essential considering the difficulties in therapeutic management and control. In the present study, though NDM-1 was detected in only four of 61 clinical isolates of P.aeruginosa tested, these were associated with a high degree of mortality. Therefore, their identification is crucial for appropriate and early initiation of treatment and also to implement infection prevention measures directed to curtail their dissemination.

References

- 1.Yong D, Toleman MA, Giske CG, Cho HS, Sundman K, Lee K, et al. Characterization of a New Metallo-β-lactamase gene blaNDM-1 and a novel erythromycin esterase gene carried on a unique genetic structure in Klebsiella pneumoniae sequence type 14 from India. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:5046–54. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00774-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nordmann P, Poirel L, Walsh TR, Livermore DM. The emerging NDM carbapenemases. Trends Microbiol. 2011;19:588–95. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nordmann P, Dortet L, Poirel L. Carbapenem resistance in Enterobacteriaceae: here is the storm! Trends Mol Med. 2012;18:263–72. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nordmann P, Poirel L, Carrer A, Toleman MA, Walsh TR. How to detect NDM-1 producers. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:718–21. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01773-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jovcic B, Lepsanovic Z, Suljagic V, Rackov G, Begovic J, Topisirovic L, et al. Emergence of NDM-1 metallo-beta lactamase in Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates from Serbia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:3929–31. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00226-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flateau C, Janvier F, Delacour H, Males S, Ficko C, Andriamanantena D, et al. Recurrent pyelonephritis due to NDM-1 metallo-betalactamase producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a patient returning from Serbia, France, 2012. Euro Surveill. 2012;17 pii=20311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson AP, Woodford N. Global spread of antibiotic resistance: the example of New Delhi metallo- β- lactamase (NDM-1) –mediated carbapenem resistance. J Med Microbiol. 2013;62:499–513. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.052555-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lister PD, Wolter DJ, Hanson ND. Antibacterial-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Clinical impact and complex regulation of chromosomally encoded resistance mechanisms. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22:583–610. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00040-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wayne, PA: CLSI; 2011. Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, 21st Informational Supplement. CLSI document M100-S21. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee K, Lim YS, Yong D, Yum H, Chong Y. Evaluation of the Hodge test and the imipenem- EDTA double disk synergy test for differentiating metallo-β-lactamase producing isolates of Pseudomonas spp. and Acinetobacter spp. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:4623–9. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.10.4623-4629.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miriagou V, Cornaglia G, Edelstein M, Galani I, Giske CG, Gniadkowski M, et al. Acquired carbapenemases in Gram-negative bacterial pathogens: detection and surveillance issues. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16:112–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.03116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deshpande P, Rodrigues C, Shetty A. New Delhi Metallo beta lactamase (NDM-1) in Enterobacteriaceae: treatment options with carbapenems compromised. J Assoc Physicians India. 2010;58:147–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manchanda V, Rai S, Gupta S, Rautela RS, Chopra R, Rawat DS, et al. Development of TaqMan real-time polymerase chain reaction for the detection of the newly emerging form of carbapenem resistance gene in clinical isolates of Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Acinetobacter baumannii. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2011;29:249–53. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.83907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hujer KM, Hujer AM, Hulten EA, Bajaksouzian S, Adams JM, Donskey CJ, et al. Analysis of antibiotic resistance genes in multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter sp. isolates from military and civilian patients treated at the Walter Reed Army medical center. Antimicrob agents Chemother. 2006;50:4114–23. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00778-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ellington MJ, Kistler J, Livermore DM, Woodford N. Multiplex PCR for rapid detection of genes encoding acquired metallo-beta-lactamases. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;59:321–2. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaase M, Nordmann P, Wichelhaus TA, Gatermann SG, Bonnin RA, Poirel L. NDM-2 carbapenemase in Acinetobacter baumannii from Egypt. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:1260–2. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen Y, Zhou Z, Jiang Y, Yu Y. Emergence of NDM-1-producing Acinetobacter baumannii in China. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:1255–9. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]