Abstract

Application of a direct-current electrical field for very short times can serve as a practical nonthermal procedure to reduce or modify the microbial distribution in gel beads. The viability of Escherichia coli and Serratia marcescens entrapped in alginate and agarose beads decreases as the field intensity and duration of electrical field increase.

Gels consist of two components: a liquid and a network of long polymer molecules that hold the liquid in place and confer mechanical rigidity (1). Gels are used as foods, as water absorbents, and in specialized applications, such as soft contact lenses. Moreover, they can be used to create biomimetic systems if they are capable of both changing their size and shape and converting chemical energy into mechanical work (21). Gels can be used for drug delivery in the form of injectable microspheres or implant systems (12, 27). Gelling agents are used in the construction of artificial muscles (20) and in many biomedical applications of microencapsulation (15), for example, in building multilayer capsules for transplantation (23) or to treat diabetes (14).

Whether polymers are used to compose multicomponent gels serving as foods (25), planned for biomedical applications such as transplantation, or used to produce naturally based carriers for the encapsulation of microbial and fungal cells in the food, biotechnology, and agricultural industries (17, 18), special care should be applied to their microbial condition. These gels should be free of bacterial contamination or carry reduced bacterial populations.

Many methods, such as heat sterilization, UV irradiation, addition of chemicals, and electrical treatments (2, 3), are currently used to reduce bacterial contamination in gels and in other food products (10). The last method is used in the medical field (e.g., for reduction of bacteria in plastic intravascular cannulae, intravascular catheters, and intact skin) (4, 7, 16) and in the food-processing industry (as a nonthermal method for the sterilization of liquid foods) (3). Reports of bacterial count reduction by applications of electric fields in semisolid or solid foods are limited and do not describe the effects of low-direct-current (DC) electrical fields (3, 10). The objectives of this study are to demonstrate that at least in principle, application of a low-DC electrical field for very short times can serve as a practical, nonthermal method of reducing or modifying microbial distribution in agar and alginate gel beads, serving as model systems for the above-listed tasks.

Culture medium and bacterial growth.

For entrapment, the biocontrol agent Serratia marcescens (19; C. Zohar-Perez, I. Chet, and A. Nussinovitch, submitted for publication) and a fluorescent kanamycin-resistant mutant of Escherichia coli (kindly provided by Johan Leveau, KNAW, Heteren, The Netherlands) were used as model gram-negative microorganisms. The bacteria were grown in Luria broth (LB) or on Luria agar (LA) (2% [wt/vol] agar) at 30°C for S. marcescens or media amended with 25 μg of kanamycin/ml at 37°C for E. coli. After 24 h they reached a concentration of ∼109 cells/ml. Bacterial cells were separated by centrifugation at 4,100 × g in a refrigerated superspeed centrifuge (Universal 16R; Hettich) for 15 min at 20°C and suspended in sterile distilled water.

Preparation of the immobilization complex.

Alginate (60 to 70 kDa, M:G ratio, 61:39; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) was dissolved in distilled water. An agarose (gelling temperature of ∼25°C; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) solution was prepared by dissolving the respective gum powder in distilled water until the boiling temperature was reached and holding it at that temperature for at least 1 min. Glycerol (final concentration, 30% [wt/wt]) was added to the alginate and agarose (final concentration, 2% [wt/wt]) solutions at room temperature (20 ± 2°C) and 50°C, respectively. The mixtures were sterilized by autoclaving. S. marcescens or E. coli (∼1010 cells/ml) organisms were then added (at room temperature) at a 1:9 volumetric ratio to the alginate-glycerol solution. This final mixture was dripped into a 1% (wt/wt) sterile solution of CaCl2 (∼100 mM) and stirred for 30 min (at room temperature). A spontaneous cross-linking reaction produced spherical gel beads with an average diameter of 4.2 ± 0.1 mm, containing ∼108 cells/bead (28-30). The bacteria were also added at a 1:9 volumetric ratio to the agarose-glycerol solution (after cooling to 35°C). The beads were produced by dropping the final mixture into distilled water through an ∼5-mm mineral oil layer (Frutarom LTD., Haifa, Israel) and storing it for 2 h at 4°C, resulting in spherical beads with an average diameter of 4.3 ± 0.2 mm, containing ∼108 cells/bead (Zohar-Perez et al., submitted).

Electrical treatment.

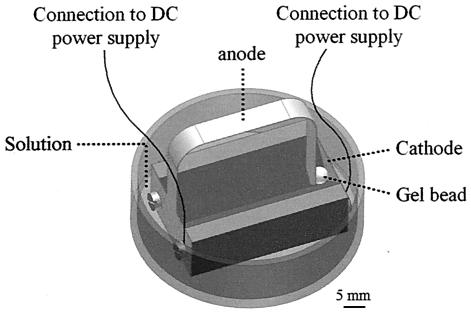

A special apparatus was designed for the application of a DC electrical field to the gel beads (Fig. 1). Alginate and agarose beads entrapping E. coli or S. marcescens were interposed between a pair of platinum (Pt) electrodes (Holland Moran LTD., Yehud, Israel) and immersed in distilled water (at room temperature). The Pt electrodes applied a constant voltage ranging from 2 to 30 V (5 to 80 V/cm, 0 to 0.1 A) across the beads by means of a DC power supply (Advice Electronics Ltd., Rosh Ha-ayen, Israel). The volumetric ratio between the solution and the bead was ∼10 (in preliminary experiments, the volumetric ratio between the solution and the bead varied from ∼2.5 to ∼500 times the volume of the bead; no changes in the rate or mode of shrinkage were detected at any of these ratios).

FIG. 1.

Custom-made apparatus for application of DC electrical field to gel beads. The electrodes were connected to a DC power supply (not in picture).

Temperature measurements.

Temperatures at the bead surface and in the immersion liquid (at different spots) were determined by a data-logging K/J thermometer and appropriate thermocouples (TES Electrical Electronic Corp., Taipei, Taiwan).

Bacterial cell counts.

Viable cell counts inside the beads, before and immediately after electrification, were determined after dissolving the alginate beads in a 2% (wt/wt) sterile sodium citrate solution and vigorous shaking (400 rpm) to total dissolution (∼10 min) or by grinding the agarose beads in an Ultra-turrax (Janke & Kunkel, Breisgau, Germany). The cells released from the beads were incubated as already described for plate counts.

Statistical analysis.

Results represent the averages of three independent experiments. In every test, two beads were evaluated. Statistical analyses were conducted with JMP software (22), including analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the Tukey-Kramer Honestly Significant Difference Method for comparisons of means. A P value of ≤0.05 was considered significant.

We report here, for the first time, the effects of a direct application of a low-DC electrical field on entrapped bacteria in individual agarose or alginate beads. This is of practical interest, since gels can resemble many foods and are used for drug release, for transplantation, as artificial organs, and to mimic thick biofilms (1, 8, 9, 11, 24, 25). Furthermore, gels have many other potential uses and as such may require less conventional methods to reduce, change, or even sterilize their inherent or embedded entrapped bacterial population. The potential scaling-up of such processes (i.e., electrification of many beads at one time) has resulted in the generation of even greater interest (A. Nussinovitch and R. Zvitov, Extraction of pigments, minerals and other contents of plant material by DC electrical fields; provisional U.S. patent application no. 60/451,271, March 2004). The viability of the gram-negative bacteria entrapped in alginate and agarose beads decreased as the field intensity and the duration of the electrical field increased. To ensure viable cell growth, we used a rich culture medium (containing all bacterium-specific nutrient demands). In addition, the incubation time was prolonged to 1 week. This plate count method is widely used and was previously mentioned for evaluating the survival of bacteria after UV radiation, freeze-drying, and long storage time (5, 6, 8, 29). Only negligible temperature changes were detected (up to 4.5°C) during the electrical application in both the beads and the surrounding fluid, and the lethal effect was therefore not thermal. In addition, it was previously demonstrated by inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry (31; R. Zvitov and A. Nussinovitch, Abstr. 6th Int. Hydrocolloids Conf., abstr. p-51, 2002) that no metal is released into the gel while applying the current, thus eliminating this as a possible killing factor.

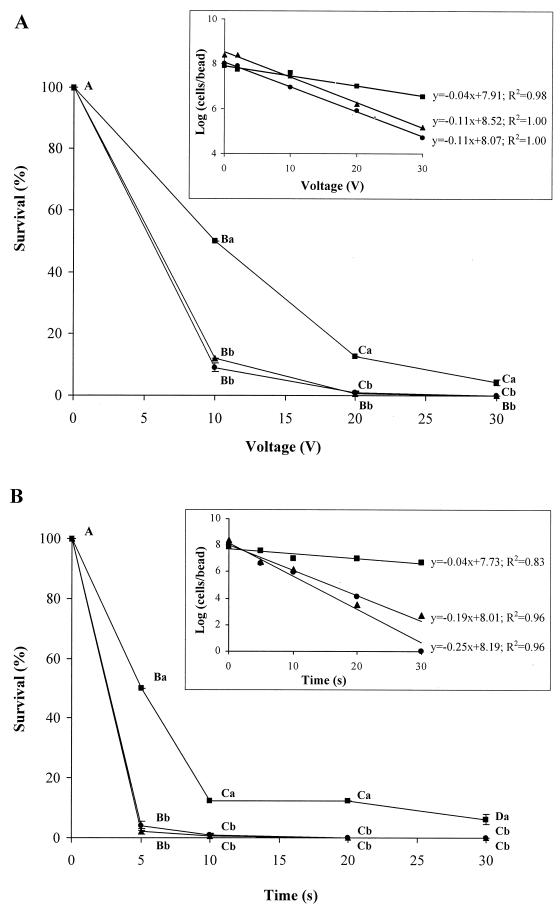

Figure 2 presents the effects of constant voltage (20 V) for different times of application (Fig. 2A) and the effects of constant application time (10 s) at different voltages on the viabilities of the different entrapped populations (Fig. 2B). At constant voltage, 10 s was enough to reduce the bacterial population by 90 to 99%. At constant time, voltages of 20 V (50 V/cm) and up were sufficient to reduce the entrapped population by the same rates (Fig. 2B). Presented as log (cells/bead) versus time or voltage (insets in Fig. 2), these data reveal that bacteria entrapped within agarose and alginate beads do not respond similarly, as might have been expected a priori for such systems. For both electrification applications, whether they consisted of constant voltage and changing time or constant time and changing voltage, similar reduction rates (slopes) of −0.040 ± 0.005 were observed for the bacteria entrapped within the agarose beads. For the bacteria entrapped within the alginate beads, the reduction rates fluctuated more, between −0.11 and −0.25. In other words, considerably higher reductions in bacterial counts were observed when they were entrapped in an agarose matrix than when they were in alginate beads. These results could be the consequence of many combined factors. First, the agarose matrix is physically less influenced (shrinkable) than alginate (although both had the same gum concentration in the gel) by the low-DC electrical field because of its noncharged polysaccharide. This interesting fact has been previously explained in detail (31, 33). Of course, the effect of the electrical field on the matrix influences the viability of the entrapped bacteria within that matrix, but this complex relationship is not fully understood and was beyond the scope of this study. In addition, it should be mentioned that a longer study is still required in order to eliminate the possibility that some cells are merely temporarily de-energized and not dead.

FIG. 2.

Survival of E. coli and S. marcescens entrapped in alginate and agarose gel beads during electrical field application of various voltages for a constant duration of 10 s (A) or various durations at a constant voltage of 20 V (B). •, E. coli in alginate beads; ▪, E. coli in agarose beads; ▴, S. marcescens in alginate beads. The values represent averages ± standard deviations. Values followed by the same letter are not significantly different (P ≤ 0.05); statistical differences in survival at the same voltage or time application are represented by lowercase letters a, b, and c; statistical differences in survival of each combination of beads and bacteria (i.e., E. coli in alginate beads, E. coli in agarose beads, and S. marcescens in alginate beads) with ascending voltage or time are represented by uppercase letters A, B, and C.

The electrodes that sandwiched the gel bead while the voltage was being applied have a more considerable physical “imprint” influence on its surface (31, 32; Zvitov and Nussinovitch, 6th Int. Hydrocolloids Conf.). It was observed that for alginate beads, because of their nonhomogeneous shrinkage during formation (Zohar-Perez et al., submitted), the count distribution on their surface was higher than inside them, in contrast to the more homogeneous bacterial distribution observed with agarose beads. Thus, the considerable physical effect of the electrodes on the bead surface may be contributing to the higher bacterial reduction rates observed with alginate beads, independent of the types of bacteria involved.

From Fig. 2 it is also clear that this controllable electrical treatment of bacteria entrapped in gels can completely kill the bacteria or only reduce the outer surface population. The latter could be applicable in cases where bacteria are entrapped in gels for slow-release purposes, such as biocontrol in agriculture (26, 28) or for cheese fermentation in the food industry (5, 6, 13); for example, when a delayed action of the entrapped bacteria on plant-pathogenic fungi is desired (when controlling plant diseases that develop at later stages of plant growth, as opposed to sprout diseases), then beads containing viable bacteria only on their interior surfaces could be useful.

The low-DC electrical treatment reduced the numbers of two types of gram-negative bacteria in gel beads, which could serve as models for various systems. Using different microorganisms is definitely an issue to be further examined. The reduction of the bacteria by a few orders of magnitude, without elevating the temperature of the specimen, is in itself unique.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Department of Instrumental Design at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, especially B. Pasmantirer, J. Ankaoua, and A. Einhorn, who helped us design and construct the electrical apparatus.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aguilera, J. M. 1992. Generation of engineered structures in gels, p. 387-421. In H. G. Schwartzberg and R. W. Hartel (ed.), Physical chemistry of foods. Marcel Dekker, New York, N.Y.

- 2.Barbosa-Canovas, G. V., M. M. Gongora-Nieto, U. R. Pothakamury, and B. G. Swanson. 1999. Preservation of foods with pulsed electric fields. Academic Press, Washington, D.C.

- 3.Barbosa-Canovas, G. V., and Q. H. Zhang. 2001. Pulsed electric fields in food processing: fundamental aspects and applications. Technomic Publishing Co., Washington, D.C.

- 4.Bolton, L., B. Foleno, B. Means, and S. Petruchelli. 1980. Direct-current bactericidal effect on intact skin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 18:137-141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Champagne, C. P., N. Gardner, E. Brochu, and Y. Beaulieu. 1991. The freeze-drying of lactic acid bacteria. A review. Can. Inst. Sci. Technol. J. 24:118-128. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Champagne, C. P., N. J. Gardner, L. Soulignac, and J. P. Innocent. 2000. The production of freeze-dried immobilized cultures of Streptococcus thermophilus and their acidification properties in milk. J. Appl. Microbiol. 88:124-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crocker, I. C., W. K. Liu, S. E. Tebbs, P. O. Byrne, and S. J. Elliott. 1992. A novel electrical method of the preservation of microbial colonization of intravascular cannulae. J. Hosp. Infect. 22:7-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elasri, M. O., and R. V. Miller. 1999. Study of the response of a biofilm bacterial community to UV radiation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:2025-2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eskin, N. A. M., H. M. Henderson, and R. J. Townsend. 1971. Biochemistry of foods. Academic Press, New York, N.Y.

- 10.Guillou, S., and N. E. Murr. 2002. Inactivation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae in solution by low-amperage electric treatment. J. Appl. Microbiol. 92:860-865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hunik, J. H., M. P. van den Hoogen, W. de Boer, M. Smit, and J. Tramper. 1993. Quantitative determination of the spatial distribution of Nitrosomonas europaea and Nitrosomonas agilis cells immobilized in κ-carrageenan gel beads by specific fluorescent-antibody labeling technique. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:1951-1954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeong, B., Y. H. Bae, D. S. Lee, and S. W. Kim. 1997. Biodegradable block copolymers as injectable drug-delivery systems. Nature 388:860-862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim, K. I., Y. J. Baek, and Y. H. Yoon. 1996. Effects of rehydration media and immobilization in Ca-alginate on the survival of Lactobacillus casei and Bifidobacterium bifidum. Korean J. Dairy Sci. 18:193-198. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lacy, P. E. 1995. Treating diabetes with transplanted cells. Sci. Am. 273:54-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lim, F. 1984. Biomedical applications of microencapsulation. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Fla.

- 16.Liu, W. K., S. E. Tebbs, P. O. Byrne, and S. J. Elliott. 1993. The effect of electric current on bacteria colonising intravenous catheters. J. Infect. 27:261-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nussinovitch, A. 1997. Hydrocolloid applications: gum technology in the food and other industries. Blackie Academic & Professional, London, United Kingdom.

- 18.Nussinovitch, A. 2003. Water-soluble polymer applications in foods. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 19.Ordentlich, A., Y. Elad, and I. Chet. 1987. Rhizosphere colonization by Serratia marcescens for the control of Sclerotium rolfsii. Soil Biol. Biochem. 19:747-751. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Osada, Y., J. P. Gong, and K. Sawahata. 1991. Synthesis, mechanism, and application of an electro-driven chemomechanical system using polymer gels. J. Macromol. Sci. Chem. Part A 28:1189-1205. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Osada, Y., and S. B. Ross-Murphy. 1993. Intelligent gels. Sci. Am. 268:42-47. [Google Scholar]

- 22.SAS Institute. 1995. JMP statistics and graphics guide, version 3.1. SAS Institute Inc., Cary, N.C.

- 23.Schneider, S., P. J. Feilen, V. Slotty, D. Kampfner, S. Preuss, S. Berger, J. Beyer, and R. Pommersheim. 2001. Multilayer capsules: a promising microencapsulation system for transplantation of pancreatic islets. Biomaterials 22:1961-1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strathmann, M., T. Griebe, and H. C. Flemming. 2000. Artificial biofilm model—a useful tool for biofilm research. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 54:231-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tolstoguzov, V. B., and E. E. Braudo. 1983. Fabricated foodstuffs as multicomponent gels. J. Texture Stud. 14:183-212. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trevors, J. T., J. D. van Elsas, H. Lee, and L. S. van Overbeek. 1992. Use of alginate and other carriers for encapsulation of microbial cells for use in soil. Microb. Releases 1:61-69. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Youxin, Y., and K. Thomas. 1993. Synthesis and properties of biodegradable ABA triblock copolymers consisting of poly(l-lactic acid) or poly(l-lactic-co-glycolic acid) A-blocks attached to central poly(oxyethylene) B-blocks. J. Control. Release 27:247-257. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zohar-Perez, C., E. Ritte, L. Chernin, I. Chet, and A. Nussinovitch. 2002. Entrapment of chitinolytic Pantoae agglomerans by cellular dried alginate-based carriers. Biotechnol. Prog. 18:1133-1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zohar-Perez, C., L. Chernin, I. Chet, and A. Nussinovitch. 2003. Structure of dried cellular alginate matrix containing fillers provides extra protection for microorganisms against UVC radiation. Radiat. Res. 160:198-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zohar-Perez, C., I. Chet, and A. Nussinovitch. 2004. Irregular surface-textural features of dried alginate-filler beads. Food Hydrocoll. 18:249-258.

- 31.Zvitov, R., and A. Nussinovitch. 2001. Weight, mechanical and structural changes induced in alginate gel beads by DC electrical field. Food Hydrocolloids 15:33-42. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zvitov, R., and A. Nussinovitch. 2001. Physico-chemical properties and structural changes in vegetative tissues as affected by direct current (DC) electrical field. Biotechnol. Prog. 17:1099-1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zvitov, R., and A. Nussinovitch. Changes induced by DC electrical field in agar, agarose, alginate and gellan gel beads. Food Hydrocoll. 17:255-263.