Abstract

Background

Two recent reports have identified the Endothelial Protein C Receptor (EPCR) as a key molecule implicated in severe malaria pathology. First, it was shown that EPCR in the human microvasculature mediates sequestration of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes. Second, microvascular thrombosis, one of the major processes causing cerebral malaria, was linked to a reduction in EPCR expression in cerebral endothelial layers. It was speculated that genetic variation affecting EPCR functionality could influence susceptibility to severe malaria phenotypes, rendering PROCR, the gene encoding EPCR, a promising candidate for an association study.

Methods

Here, we performed an association study including high-resolution variant discovery of rare and frequent genetic variants in the PROCR gene. The study group, which previously has proven to be a valuable tool for studying the genetics of malaria, comprised 1,905 severe malaria cases aged 1–156 months and 1,866 apparently healthy children aged 2–161 months from the Ashanti Region in Ghana, West Africa, where malaria is highly endemic. Association of genetic variation with severe malaria phenotypes was examined on the basis of single variants, reconstructed haplotypes, and rare variant analyses.

Results

A total of 41 genetic variants were detected in regulatory and coding regions of PROCR, 17 of which were previously unknown genetic variants. In association tests, none of the single variants, haplotypes or rare variants showed evidence for an association with severe malaria, cerebral malaria, or severe malaria anemia.

Conclusion

Here we present the first analysis of genetic variation in the PROCR gene in the context of severe malaria in African subjects and show that genetic variation in the PROCR gene in our study population does not influence susceptibility to major severe malaria phenotypes.

Introduction

Endothelial protein C receptor (EPCR) is found at the surface of the endothelial cells of diverse tissue origin [1]. It functions as the principal regulatory molecule for protein C that as activated protein C (APC) exerts anticoagulant and cytoprotective functions, thereby maintaining the integrity of endothelia.

Recently, two independent studies provided evidence for an implication of EPCR in severe malaria (SM) and cerebral malaria (CM) pathologies [2], [3]. With regard to SM, EPCR was identified as an endothelial receptor for certain binding cassettes of Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP1) [2]. Turner and colleagues pinpointed the binding site of PfEMP1, which appears to be located near or directly at the domain mediating EPCR binding to protein C. It was postulated that, by occupying the protein C binding site, EPCR-mediated parasite adhesion could impair the cytoprotective and anti-inflammatory pathways. In consequence, a disruption of the endothelial layer could evoke vascular leakage, and, when these processes occur in cerebral microvessels, may result in brain hemorrhages typically observed in CM pathology. Further, expression levels of the transcript encoding the EPCR binding domain of PfEMP1 were shown to be significantly higher in P. falciparum isolates from children with CM or severe malaria anemia (SMA) compared to children with uncomplicated malaria [4]. Hence, there is additional indirect evidence for a link between PfEMP1 binding to EPCR and CM and SMA pathologies.

The second more recent study reported on a malaria-induced reduction of EPCR expression at the surface of cerebral endothelial layers in autopsies from Malawian children affected by CM [3]. Additionally, a low constitutive expression of EPCR was observed particularly in the brain. These findings might serve as an explanation for the organ-specific pathology in CM, which is induced by cytoadherence of Plasmodium-infected red blood cells (iRBCs) in brain microvessels to a wide range of additional receptors [5]. It was suggested that a low capacity of EPCR to activate protein C caused by adherence of iRBCs and adjacent cleavage of EPCR could provoke a proinflammatory and procoagulant state in affected tissues.

PROCR, the gene encoding EPCR, is located on chromosome 20 and spans approximately 6 kb of genomic DNA [6]. The gene comprises four exons. Exon I encodes an untranslated 5′ region (5′-UTR) and a signal peptide, exons II and III the extracellular domain of EPCR, and exon IV the transmembrane domain, the cytoplasmic tail and the 3′ untranslated region (3′-UTR).

Until today human genetic variation in PROCR has primarily been assessed in the context of common thrombotic disorders, such as cardiovascular disease and venous thrombosis [7], [8]. For the most part these studies examined a functionally relevant single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in PROCR, variant rs867186 A>G, which is located in exon IV. This SNP causes a serine-glycine substitution (S219G), and the G allele was associated with increased plasma levels of soluble EPCR (sEPCR), Factor VII, and protein C [9]–[11]. The G allele of rs867186 distinctly tags the PROCR haplotype A3. This haplotype was also associated with elevated plasma levels of sEPCR [12] and high levels of protein C [13]. A second functional haplotype, PROCR H1, was associated with higher amounts of APC in plasma and was found to be protective against venous thromboembolism [14]. In contrast, the A3 haplotype has been identified as a genetic risk factor for venous thrombosis, and it was hypothesized that a balanced polymorphism in PROCR could confer protection against SM at the cost of a higher risk of thrombotic disease [2]. Moreover, in a recent paper Aird et al. speculated that the same functional haplotype could also have a specific protective effect against CM, because an increased level of sEPCR could impair cytoadhesion of infected red blood cells to cerebral endothelial cells and hence prevent severe pathology in the brain [15].

Taken together, there is substantial evidence that human genetic variation affecting EPCR functionality could influence severe malaria phenotypes, rendering PROCR a promising candidate for an association study. Here, we assessed the influence of common, rare, and haplotypic genetic variation in the human PROCR gene on SM phenotypes in a large case-control study comprising more than 3,700 subjects [16] from the Ashanti Region in Ghana, West Africa.

Results

Variant discovery in the regulatory and coding regions of the PROCR gene was conducted in 3,771 unrelated individuals from the Ashanti Region in Ghana. The study group included 1,905 children with SM, 431 of whom were classified as CM cases, 1,226 as SMA cases, and 1,866 apparently healthy control individuals. As a result of a high resolution melting (HRM) screen, a total of 41 genetic variants were detected, of which 17 were novel. Fifteen variants were found to be singletons, 17 had a minor allele frequency (MAF) below 1% and nine variants were found to have a MAF of 1% or greater (Table 1). Six SNPs in exonic regions caused non-synonymous amino acid exchanges in the receptor protein. One of these, a substitution of an aspartic acid by a glycine residue at position 23 (D23G) was previously unknown.

Table 1. Genetic variants in the PROCR gene found in 3,771 Ghanaian children.

| SNP ID | Position Chr19 (build37) | Major/Minor Allele | Region | Relative positiona | AA exchange | Novel | MAF cases (N = 1,905) | MAF controls (N = 1,866) | |

| 1 | ss1457457875 | 33758811 | G/A | 5′-UTR | c.-1147 | YES | - | Singleton | |

| 2 | rs113601425 | 33758824 | C/T | c.-1134 | 0.007 | 0.007 | |||

| 3 | ss1457457916 | 33758834 | A/G | c.-1124 | YES | 0.001 | 0.001 | ||

| 4 | ss1457457937 | 33758983 | C/G | c.-975 | YES | 0.001 | 0.002 | ||

| 5 | rs112681065 | 33759055 | C/G | c.-903 | 0.006 | 0.008 | |||

| 6 | ss1457457959 | 33759070 | TA/- | c.-888 | YES | Singleton | - | ||

| 7 | ss1457457984 | 33759072 | CACA/- | c.-886 | YES | Singleton | - | ||

| 8 | ss1457458010 | 33759093 | C/A | c.-865 | YES | 0.002 | 0.001 | ||

| 9 | rs115088244 | 33759104 | G/T | c.-854 | 0.077 | 0.084 | |||

| 10 | rs146473859 | 33759128 | C/G | c.-830 | 0.001 | 0.001 | |||

| 11 | ss1457458032 | 33759145 | T/C | c.-813 | YES | - | Singleton | ||

| 12 | rs2069940 | 33759272 | C/G | c.-686 | 0.018 | 0.018 | |||

| 13 | rs2069941 | 33759386 | C/T | c.-572 | 0.013 | 0.012 | |||

| 14 | ss1457458053 | 33759599 | A/G | c.-359 | YES | Singleton | - | ||

| 15 | rs113347910 | 33759639 | C/A | c.-319 | 0.038 | 0.028 | |||

| 16 | rs372603647 | 33759656 | C/- | c.-301 | - | Singleton | |||

| 17 | rs139617753 | 33759867 | C/G | Ex1-UTR | c.-91 | - | Singleton | ||

| 18 | ss1457458073 | 33759903 | C/T | c.-55 | YES | 0.001 | 0.001 | ||

| 19 | ss1457458095 | 33759972 | G/A | Ex1 | c.15 | L5L | YES | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| 20 | rs145917629 | 33759978 | G/A | c.21 | P7P | 0.004 | 0.003 | ||

| 21 | ss1457458118 | 33760025 | A/G | c.68 | D23G | YES | Singleton | - | |

| 22 | rs2069948 | 33762489 | T/C | In1 | c.71-16 | 0.125 | 0.126 | ||

| 23 | rs141487483 | 33762664 | A/G | Ex2 | c.230 | E77G | 0.002 | 0.003 | |

| 24 | rs2069952 | 33763951 | T/C | In2 | c.323-20 | 0.132 | 0.14 | ||

| 25 | COSM1222127 | 33764042 | G/A | Ex3 | c.395 | E132K | - | Singleton | |

| 26 | rs144485700 | 33764082 | C/T | c.434 | P145L | 0.003 | 0.001 | ||

| 27 | rs201040729 | 33764137 | C/T | c.489 | F163F | Singleton | - | ||

| 28 | rs116737636 | 33764292 | C/T | In3 | c.601+43 | Singleton | - | ||

| 29 | rs148966205 | 33764458 | T/A | c.602-43 | 0.001 | - | |||

| 30 | rs145801152 | 33764542 | G/A | Ex4 | c.643 | V215I | 0.001 | - | |

| 31 | rs867186 | 33764554 | A/G | c.655 | S219G | 0.057 | 0.059 | ||

| 32 | rs9574 | 33764632 | G/C | 3'-UTR | c.*16 | 0.132 | 0.139 | ||

| 33 | rs141265473 | 33764667 | G/C | c.*51 | 0.006 | 0.004 | |||

| 34 | ss1457458141 | 33764697 | C/G | c.*81 | YES | Singleton | - | ||

| 35 | ss1457458164 | 33764702 | A/G | c.*86 | YES | - | Singleton | ||

| 36 | ss1457458186 | 33764703 | C/A | c.*87 | YES | - | Singleton | ||

| 37 | rs146262354 | 33764758 | C/G | c.*142 | 0.006 | 0.004 | |||

| 38 | rs115542162 | 33764978 | C/T | c.*362 | 0.032 | 0.030 | |||

| 39 | ss1457458207 | 33765308 | A/G | c.*692 | YES | - | 0.002 | ||

| 40 | ss1457458230 | 33765332 | A/G | c.*710 | YES | - | Singleton | ||

| 41 | ss1457458251 | 33765355 | A/G | c.*739 | YES | 0.001 | 0.001 |

AA, amino acid; Ex, exon; In, intron; MAF, minor allele frequency.

Reference sequence NCBI NM_006404.4.

Association testing of the nine SNPs with MAFs ≥1% did not show any evidence for an association with SM, CM, or SMA (Table 2). A trend for an association with both, SM and SMA, was found for the A allele of promoter variant rs113347910 (SM: odds ratio [OR] 1.32, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.01–1.73, p = 0.04; SMA: OR 1.39, 95% CI 1.01–1.90, p = 0.04), however, the associations did not hold after adjusting for multiple testing (pcorrected = 0.28, factor 7).

Table 2. Association tests of PROCR SNPs (MAF ≥1%) with severe malaria, cerebral malaria, and severe malaria anemia.

| Severe Malaria | Cerebral Malaria | Severe Malaria Anemia | ||||||||

| Ncases = 1,905 | Ncases = 431 | Ncases = 1,226 | ||||||||

| Ncontrols = 1,866 | Ncontrols = 1,866 | Ncontrols = 1,866 | ||||||||

| No. | SNP ID | Major/Minor Allele | HWE | MAF (aff/unaff) | OR (95% CI)a | p-valuea | OR (95% CI)a | p-valuea | OR (95% CI)a | p-valuea |

| 1 | rs115088244 | G/T | 0.288 | 0.08/0.08 | 0.90 (0.75–1.07) | 0.228 | 1.08 (0.83–1.41) | 0.566 | 0.86 (0.69–1.05) | 0.140 |

| 2 | rs2069940 | C/G | 1 | 0.02/0.02 | 0.93 (0.65–1.35) | 0.717 | 0.99 (0.59–1.74) | 0.975 | 0.91 (0.60–1.40) | 0.673 |

| 3 | rs2069941 | C/T | 1 | 0.01/0.01 | 1.07 (0.73–1.61) | 0.772 | 0.58 (0.25–1.38) | 0.222 | 1.09 (0.37–1.80) | 0.222 |

| 4 | rs113347910 | C/A | 1 | 0.04/0.03 | 1.32 (1.01–1.73) | 0.044 | 1.41 (0.94–2.11) | 0.099 | 1.39 (1.01–1.90) | 0.042 |

| 5 | rs2069948 | T/C | 0.914 | 0.13/0.13 | 0.99 (0.86–1.15) | 0.943 | 1.11 (0.89–1.38) | 0.369 | 1.03 (0.87–1.22) | 0.766 |

| 6 | rs2069952 | T/C | 0.628 | 0.13/0.14 | 0.93 (0.81–1.07) | 0.335 | 1.02 (0.82–1.26) | 0.885 | 0.97 (0.83–1.15) | 0.760 |

| 7 | rs867186 | A/G | 0.831 | 0.06/0.06 | 0.87 (0.71–1.07) | 0.202 | 1.01 (0.74–1.39) | 0.942 | 0.81 (0.63–1.03) | 0.087 |

| 8 | rs9574 | G/C | 0.846 | 0.13/0.14 | 0.94 (0.82–1.08) | 0.372 | 1.03 (0.83–1.28) | 0.792 | 0.98 (0.83–1.15) | 0.772 |

| 9 | rs115542162 | C/T | 0.687 | 0.03/0.03 | 0.96 (0.73–1.25) | 0.748 | 1.15 (0.77–1.74) | 0.492 | 0.89 (0.65–1.22) | 0.461 |

Aff, affected individuals; CI, confidence interval; HWE, Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium; MAF, minor allele frequency; OR, odds ratio; unaff, unaffected individuals.

Results of logistic regression analyses assuming an additive mode of inheritance adjusted for gender, age, and ethnicity

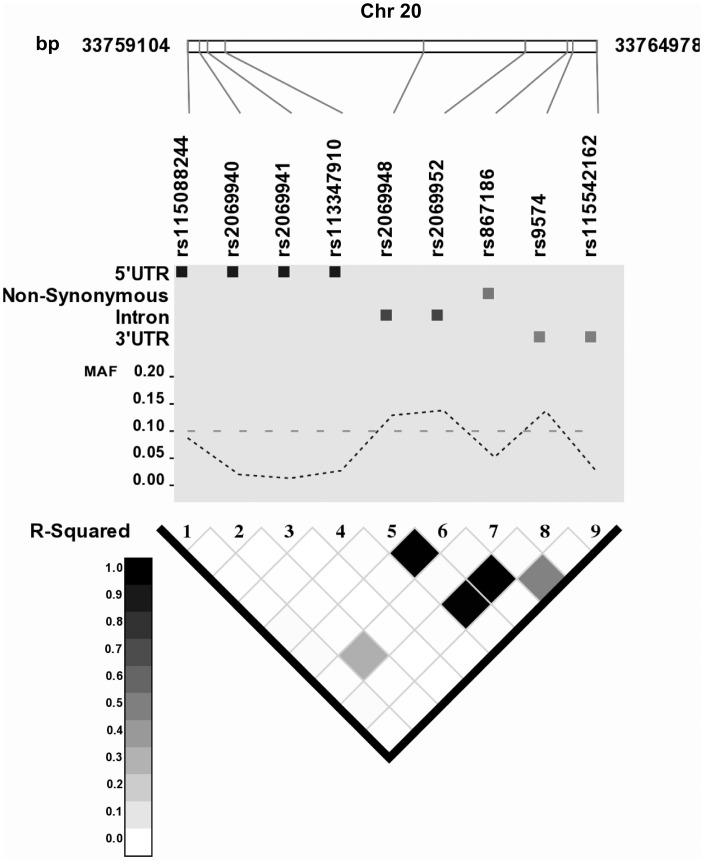

Linkage disequilibrium (LD) between SNPs with MAFs ≥1% was found to be generally low, except for three pairs of SNPs, which were highly correlated (r2>0.99). These were two intronic variants, rs2069948 and rs2069952, and variant rs9574, which is located in the 3′-UTR. Other pairwise r2 values did not exceed 0.48 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Linkage disequilibrium plot of the PROCR gene locus.

The plot was generated on the basis of SNPs (MAF ≥1%) in healthy control individuals. Grey-scale squares represent pairwise r2 values ranging from 0–1.

Power calculations resulted in a power of 100%, 96%, and 100% to detect a genotype-phenotype association in the SM, CM, and SMA study groups, respectively, when assuming a genotype relative risk of at least 2 and a MAF ≥5%. In the case of low frequency SNPs (MAF ≥1%) the power obtained was 82% in the SM group, 19% in the CM group, and 66% in the SMA group.

Reconstruction of haplotypes generated seven full-length haplotypes with a global MAF ≥1%. Of these, haplotype PROCR-1 was the most prominent one with estimated frequencies of 68 and 69% in the control and case groups, respectively (Table 3). Haplotype PROCR-4 was found more frequently in cases than in controls (AF 4% in cases and 3% in controls). Whereas the difference was statistically significant in the haplotypic-specific score test (p = 0.04, pempirical = 0.03), the global test-statistic produced a p-value of 0.20, indicating no association of full-length haplotypes with SM, CM, or SMA.

Table 3. Association tests of PROCR haplotypes with severe malaria, cerebral malaria, and severe malaria anemia.

| Severe malaria | Cerebral Malaria | Severe Malaria Anemia | ||||||

| Ncases = 1,905 | Ncases = 431 | Ncases = 1,226 | ||||||

| Ncontrols = 1,866 | Ncontrols = 1,866 | Ncontrols = 1,866 | ||||||

| Haplotype | 1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8-9a | Frequency (aff/unaff) | p-valueb | Simulatedc p-value | p-valueb | Simulatedc p-value | p-valueb | Simulatedcp-value |

| Ncases = 1,905 Ncontrols = 1,866 | ||||||||

| PROCR-1 | GCCCTTAGC | 0.69/0.68 | 0.296 | 0.294 | 0.407 | 0.405 | 0.326 | 0.291 |

| PROCR-2 | GCCCCCACC | 0.14/0.14 | 0.357 | 0.348 | 0.820 | 0.832 | 0.690 | 0.676 |

| PROCR-3 | TCCCTTAGC | 0.07/0.08 | 0.208 | 0.196 | 0.543 | 0.557 | 0.128 | 0.115 |

| PROCR-4 | GCCATTAGC | 0.04/0.03 | 0.040 | 0.030 | 0.108 | 0.112 | 0.038 | 0.041 |

| PROCR-5 | GCCCTTGGT | 0.03/0.03 | 0.925 | 0.929 | 0.504 | 0.502 | 0.589 | 0.608 |

| PROCR-6 | GGCCTTGGC | 0.02/0.02 | 0.663 | 0.660 | 0.909 | 0.912 | 0.433 | 0.433 |

| PROCR-7 | GCTCTTAGC | 0.01/0.01 | 0.697 | 0.710 | 0.265 | 0.293 | 0.784 | 0.808 |

Aff, affected individuals; unaff, unaffected individuals.

Refers to SNP number as designated in Table 2.

Results of haplotypic-specific score tests adjusted for gender, age, and ethnicity assuming an additive mode of inheritance.

Simulation p-values are computed based on a permuted re-ordering of the trait and covariates in Haplo Stats [29].

The previously described functional PROCR haplotype A3, tagged by the G-allele of variant rs867186, was present in two haplotypes in the Ghanaian study group, PROCR-5 and PROCR-6, with frequencies of 3% and 2%, respectively. Neither the risk for SM nor for CM or SMA appeared to be influenced by any of the two haplotypes (Table 3). Haplotype PROCR-2, tagged by the C-allele of rs9574, which had previously been found to influence APC levels, had an estimated frequency of 14% in both, cases and controls. In our study group there was no sign for an association with risk of or protection from SM, CM, or SMA. This also applied to sub-haplotypes in the sliding-window analyses.

Four different algorithms were applied in order to test for an accumulation of rare variants in either the case or control groups. None of the approaches, including univariate and multivariate collapsing tests with varying thresholds, provided evidence for a joint effect of rare variants on the phenotypes tested (Table 4).

Table 4. PROCR rare variant analyses including SNPs with MAF ≤1%.

| Severe malaria | Cerebral malaria | Severe malaria anemia | |

| 32 variants | 27 variants | 28 variants | |

| p-value | p-value | p-value | |

| Univariate tests | |||

| CMC | 0.370 | 0.410 | 0.780 |

| WSS | 0.343 | 0.334 | 0.721 |

| VT test | 0.267 | 0.122 | 0.579 |

| C-alpha | 0.270 | 0.405 | 0.229 |

| Multivariate tests a | |||

| CMC | 0.445 | 0.387 | 0.883 |

| WSS | 0.248 | 0.253 | 0.700 |

| VT test | 0.835 | 0.224 | 0.838 |

CMC, combined and multivariate collapsing; WSS, weighted sum statistic; VT, variable thresholds methods.

Adjusted for age, gender, and ethnic group.

In conclusion, the discovered genetic variants in regulatory and coding regions of the PROCR gene were not found to influence susceptibility to SM, CM, or SMA in our study group.

Discussion

After two recent reports on EPCR and its role in SM pathology, PROCR, the gene encoding EPCR, was considered a promising candidate to substantiate the in-vitro and ex-vivo data presented by a genetic association study. Here, we studied variation of PROCR in a large case-control group of SM from the Ashanti Region in Ghana, West Africa. None of the three approaches, including association testing of single SNPs, haplotypes, and rare variants, provided evidence for an association between variants in PROCR and the susceptibility to SM, CM, or SMA.

The lack of association may have several different explanations. First of all, it is conceivable, that, although against the current hypothesis, genetic variation in the gene does not alter susceptibility to SM phenotypes.

Second, not finding associations could be due to limitations of the study. For instance, additional genetic variation with functional relevance for PROCR gene expression, which may be located in cis or trans of the gene locus, could have remained undiscovered. As previous studies have shown PROCR gene transcription can be initiated at various sites. Sequences located −83 and −79 basepairs (bp) upstream of the translation initiation site have been described as alternative transcription start sites [6], [17]. Besides the common functional elements at the proximal promoter of PROCR, an additional regulatory element 5.5 kb upstream of the translation start was reported [18]. It was shown to exert enhancer activity in a cell-type specific manner. The possibility that genetic variation in this segment has an effect on PROCR gene expression and in turn on SM susceptibility appeared to be small because its sequence was found to be little diverse [18]. In this 500 bp enhancer region only one SNP (rs8119351) was found with a MAF>5% in genomic sequences of 669 individuals with African ancestry as part of the 1000 Genomes Project (http://www.1000genomes.org; assessed on 01st August 2014). Nevertheless, when we tested this additional SNP in this study group no association was found (OR 0.80, 95% CI 0.61–1.04, pcorrected = 0.63).

Until now, there is one study that investigated variant rs867186 in the context of SM [19]. In that study, the authors reported evidence for an association of the GG genotype with protection from severe malaria in 707 Thai patients. However, results from that study are not totally convincing due to the fact that a statistically significant association was solely found when assuming a recessive mode of inheritance (MOI) (p = 0.026) and correction for multiple testing was disregarded. In our SM study group, when assuming the recessive MOI, the association test resulted in an OR of 1.32 (95% CI 0.39–4.47, p-value = 0.658), clearly failing to show any genotype-phenotype association.

In addition to the association analysis described here we screened results from a genome-wide association study on SM which included 2,153 individuals from the same case-control study [20]. In that study approximately 800,000 SNPs per individual were genotyped throughout the genome. None of the genome-wide significant hits found was located in genes of molecules which have been described as part of the protein C anticoagulant and cytoprotective pathways [21]. Among others, these are protein C, Factor Va, Factor VIIIa, Thrombin, Thrombomodulin, and PAR-1.

The analyses of the potentially functional haplotypes, PROCR-2, -5, and -6, which were found to have frequencies of 14%, 3%, and 2%, respectively, did not show any evidence for association either. It is possible that these haplotypes do not exhibit the same function as described for Caucasians due to differing underlying regulatory mechanisms for PROCR gene expression in Africans. When comparing LD data and the haplotype substructure of the PROCR genomic region in Europeans with the Yoruba population from Nigeria, LD is considerably lower in the African subjects (1000 Genomes Project; www.ensembl.org), indicating inter-population genetic heterogeneity at this locus.

Further, a genotype-phenotype association in malaria may involve co-evolutionary effects between P. falciparum and its human host. Today there are numerous examples for highly specific host-pathogen interactions revealing the footprints of co-evolution at a molecular level [22], [23]. These include the invasion mechanisms of P. falciparum into the erythrocyte, which involves the RBC surface protein glycophorin C (GYPC). In the process of invasion, the P. falciparum erythrocyte-binding antigen 140 binds to GYPC on the surface of erythrocytes. A deletion in the gene of GYPC results in an RBC phenotype that cannot be invaded via this principal pathway [24]. This allele has reached a frequency of 46% in coastal areas of Papua New Guinea, where malaria is hyperendemic. Similarly, it is possible, that a specific structural variant of EPCR may be effective only against a certain type of PfEMP1 variants. In the case of a parasite strain expressing PfEMP1 conferring particularly strong binding to EPCR, a specific genetic host variant may be protective, and this variant would not necessarily be advantageous in infections with other parasites expressing other PfEMP1 variants. These highly specific protective mechanisms can only be detected when accounting for genetic and/or phenotypic substructure of the parasite population.

Another reason why existing genotype-phenotype associations may remain obscure is a lack of power. The power of a study depends on the number of study participants and MAFs and effect sizes of the alleles tested. Whereas the power was sufficient for SNPs in the SM study group, it was reduced to 19% when analysing alleles with frequencies <5% in the CM study group. Hence, the detection of associated low frequency variants (MAF <5%) with CM was underpowered, but for alleles with frequencies ≥5% the power was still appropriate with 96%.

The results presented here, although not providing evidence for associations between PROCR genetic variants and SM, CM, or SMA, do not preclude a role of PROCR genetic variation in malaria susceptibility in other settings. Moreover, the lack of association between genetic variation in PROCR and the phenotypes tested does not disagree with previous studies that support an important role of EPCR in SM and CM pathologies. Further studies, including gene expression studies of EPCR in African individuals would be helpful to determine expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs) for EPCR and to find key regulatory mechanisms of its expression in individuals exposed to P. falciparum infection.

Materials and Methods

Severe malaria case-control group

The SM case-control group comprised 1,905 severe malaria patients and 1,866 healthy control individuals. The median age of cases and control individuals was 18 and 30 months, respectively, (ranges 1–156 months in the case group and 2–161 months in the control group). Of the severe cases, 431 (22.6%) presented with CM, 1,226 (64.4%) had SMA, 28.0% presented with hyperparasitemia, and 50.0% with prostration, with partly overlapping manifestations. Recruitment of study subjects, phenotyping, and DNA extraction has been described in detail elsewhere [16], [25].

Variant discovery and genotyping

In order to screen the PROCR locus on chromosome 20 (chr20: 33,758,824–33,765,355) for genetic variants, DNA from 3,771 unrelated Ghanaian individuals (1,905 SM cases and 1,866 healthy controls) was used for HRM. Prior to the screen, genomic DNA had been whole-genome amplified by Genomiphi V2 DNA amplification kit (GE Healthcare). DNA samples were then amplified by PCR using primers that captured 1,100 bp upstream of the transcription start site, exons and their flanking regions, and 750 bp of the 3′-UTR. Oligonucleotides were designed using LightCycler Probe Design Software 2.0 (Roche Applied Science) against reference transcript NCBI NM_006404. Sequences of oligonucleotides and PCR conditions for HRM assays are listed in S1 Table. Previously unknown SNPs and singletons were confirmed by re-sequencing genomic DNA. In addition, 13 variants detected by HRM were genotyped by allele-specific hybridization in a Roche LightCycler device (S2 Table).

Association analyses of SNPs with MAFs ≥1%

Logistic regression was used to test for association of nine variants in the case-control study assuming an additive MOI in PLINK v1.07 [26]. Ethnic group, age, and gender were used as covariates in the regression model. Logistic regression analyses did not account for HbS or HbC allele carrier status of individuals. In order to account for multiple testing we used a correction factor of 7, hence, a p-value <0.007 (0.05/7) was considered significant. A factor of seven was applied because three of the nine SNPs tested were highly correlated to each other (pairwise r2>0.99; see results section), thereby reducing the number of independent statistical comparisons to seven. Variants were tested for fulfilling the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) in PLINK. Power for detecting genetic effects of variants in the case-control study was estimated with CATS [27]. For power estimations, a disease prevalence of 2% for severe malaria and p-value <0.007 were assumed.

Calculation of LD

LD-Plus was used to generate the LD plot of the PROCR genomic region [28]. The LD calculation was based on the control individuals and included PROCR variants with MAF ≥1%.

Haplotype-based association testing

Full-length haplotype analyses were done for the case-control group with the Haplo Stats package v1.4.4 [29] in R (version 3.1.0; http://www.r-project.org), including reconstructed haplotypes with estimated global frequencies ≥1%. In addition, sub-haplotypes were evaluated in sliding-window analyses capturing a minimum of two and a maximum of eight alleles. SM, CM, and SMA were used as phenotypes, and the three covariates ethnic group, age, and gender were included in the model. Empirical p-values were computed using default values.

Association analyses of rare variants (MAF <1%)

We tested for association between rare variant carrier status at PROCR and SM, CM, or SMA in the study group. Four methods were used to assess the overall genetic burden due to rare variants, namely (i) the combined and multivariate collapsing (CMC) method described by Li and Leal [30], (ii) the weighted sum statistic (WSS) described by Madsen and Browning [31], (iii) the variable-threshold (VT) model described by Price et al. [32], and (iv) the C(α) test described by Neale et al. [33], all integrated in variant tools [34]. For these analyses variants were pooled on the basis of their MAF and their cumulative effect was tested in both univariate and multivariate analyses, in which age, gender, and ethnic group were included as covariates.

Ethics statement

Ethical clearance was granted by the Committee for Research, Publications and Ethics of the School of Medical Sciences, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana. All procedures were explained to parents or guardians of the participating children in the local language, and written or thumb-printed informed consent was obtained.

Supporting Information

Oligonucleotides and PCR conditions for high resolution melting assays.

(DOC)

Oligonucleotides and PCR conditions for SNP genotyping.

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participating children and their parents and guardians. Tsiri Agbenyega represents the Kumasi team of the Severe Malaria in African Children (SMAC) network, which includes Daniel Ansong, MD, Sampson Antwi, MD, Emanuel Asafo-Adjei, MD, Samuel Blay Nguah, MD, Kingsley Osei Kwakye, MD, Alex Osei Yaw Akoto, MD, and Justice Sylverken, MD, all Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital, Kumasi.

Data Availability

The authors confirm that all data underlying the findings are fully available without restriction. All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The study was funded by the Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine (BNITM). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Gleeson EM, O'Donnell JS, Preston RJS (2012) The endothelial cell protein C receptor: cell surface conductor of cytoprotective coagulation factor signaling. Cell Mol Life Sci 69:717–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Turner L, Lavstsen T, Berger SS, Wang CW, Petersen JEV, et al. (2013) Severe malaria is associated with parasite binding to endothelial protein C receptor. Nature 498:502–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Moxon CA, Wassmer SC, Milner DA, Chisala NV, Taylor TE, et al. (2013) Loss of endothelial protein C receptors links coagulation and inflammation to parasite sequestration in cerebral malaria in African children. Blood 122:842–851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lavstsen T, Turner L, Saguti F, Magistrado P, Rask TS, et al. (2012) Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 domain cassettes 8 and 13 are associated with severe malaria in children. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:E1791–E1800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Esser C, Bachmann A, Kuhn D, Schuldt K, Förster B, et al. (2014) Evidence of promiscuous endothelial binding by Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes. Cell Microbiol 16:701–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Simmonds RE, Lane DA (1999) Structural and functional implications of the intron/exon organization of the human endothelial cell protein C/activated protein C receptor (EPCR) gene: comparison with the structure of CD1/major histocompatibility complex alpha1 and alpha2 domains. Blood 94:632–641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Reiner AP, Carty CL, Jenny NS, Nievergelt C, Cushman M, et al. (2008) PROC, PROCR and PROS1 polymorphisms, plasma anticoagulant phenotypes, and risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality in older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study. J Thromb Haemost 6:1625–1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dennis J, Johnson CY, Adediran AS, de Andrade M, Heit JA, et al. (2012) The endothelial protein C receptor (PROCR) Ser219Gly variant and risk of common thrombotic disorders: a HuGE review and meta-analysis of evidence from observational studies. Blood 119:2392–2400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Smith NL, Chen M-H, Dehghan A, Strachan DP, Basu S, et al. (2010) Novel associations of multiple genetic loci with plasma levels of factor VII, factor VIII, and von Willebrand factor: The CHARGE (Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genome Epidemiology) Consortium. Circulation 121:1382–1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tang W, Basu S, Kong X, Pankow JS, Aleksic N, et al. (2010) Genome-wide association study identifies novel loci for plasma levels of protein C: the ARIC study. Blood 116:5032–5036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kallel C, Cohen W, Saut N, Blankenberg S, Schnabel R, et al. (2012) Association of soluble endothelial protein C receptor plasma levels and PROCR rs867186 with cardiovascular risk factors and cardiovascular events in coronary artery disease patients: the Athero Gene study. BMC Med Genet 13:103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Saposnik B, Reny J-L, Gaussem P, Emmerich J, Aiach M, et al. (2004) A haplotype of the EPCR gene is associated with increased plasma levels of sEPCR and is a candidate risk factor for thrombosis. Blood 103:1311–1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pintao MC, Roshani S, de Visser MCH, Tieken C, Tanck MWT, et al. (2011) High levels of protein C are determined by PROCR haplotype 3. J Thromb Haemost 9:969–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Medina P, Navarro S, Estellés A, Vayá A, Woodhams B, et al. (2004) Contribution of polymorphisms in the endothelial protein C receptor gene to soluble endothelial protein C receptor and circulating activated protein C levels, and thrombotic risk. Thromb Haemost 91:905–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Aird WC, Mosnier LO, Fairhurst RM (2014) Plasmodium falciparum picks (on) EPCR. Blood 123:163–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. May J, Evans JA, Timmann C, Ehmen C, Busch W, et al. (2007) Hemoglobin variants and disease manifestations in severe falciparum malaria. Jama 297:2220–2226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hayashi T, Nakamura H, Okada A, Takebayashi S, Wakita T, et al. (1999) Organization and chromosomal localization of the human endothelial protein C receptor gene. Gene 238:367–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mollica LR, Crawley JTB, Liu K, Rance JB, Cockerill PN, et al. (2006) Role of a 5′-enhancer in the transcriptional regulation of the human endothelial cell protein C receptor gene. Blood 108:1251–1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Naka I, Patarapotikul J, Hananantachai H, Imai H, Ohashi J (2014) Association of the endothelial protein C receptor (PROCR) rs867186-G allele with protection from severe malaria. Malar J 13:105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Timmann C, Thye T, Vens M, Evans J, May J, et al. (2012) Genome-wide association study indicates two novel resistance loci for severe malaria. Nature 489:443–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mosnier LO, Zlokovic BV, Griffin JH (2007) The cytoprotective protein C pathway. Blood 109:3161–3172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bongfen SE, Laroque A, Berghout J, Gros P (2009) Genetic and genomic analyses of host-pathogen interactions in malaria. Trends Parasitol 25:417–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kwiatkowski DP (2005) How malaria has affected the human genome and what human genetics can teach us about malaria. Am J Hum Genet 77:171–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Maier AG, Duraisingh MT, Reeder JC, Patel SS, Kazura JW, et al. (2003) Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte invasion through glycophorin C and selection for Gerbich negativity in human populations. Nat Med 9:87–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schuldt K, Kretz CC, Timmann C, Sievertsen J, Ehmen C, et al. (2011) A -436C>A polymorphism in the human FAS gene promoter associated with severe childhood malaria. PLoS Genet 7:e1002066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MAR, et al. (2007) PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet 81:559–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Skol AD, Scott LJ, Abecasis GR, Boehnke M (2006) Joint analysis is more efficient than replication-based analysis for two-stage genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet 38:209–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bush WS, Dudek SM, Ritchie MD (2010) Visualizing SNP statistics in the context of linkage disequilibrium using LD-Plus. Bioinformatics 26:578–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schaid DJ, Rowland CM, Tines DE, Jacobson RM, Poland GA (2002) Score tests for association between traits and haplotypes when linkage phase is ambiguous. Am J Hum Genet 70:425–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Li B, Leal SM (2008) Methods for detecting associations with rare variants for common diseases: application to analysis of sequence data. Am J Hum Genet 83:311–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Madsen BE, Browning SR (2009) A groupwise association test for rare mutations using a weighted sum statistic. PLoS Genet 5:e1000384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Price AL, Kryukov GV, de Bakker PIW, Purcell SM, Staples J, et al. (2010) Pooled association tests for rare variants in exon-resequencing studies. Am J Hum Genet 86:832–838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Neale BM, Rivas MA, Voight BF, Altshuler D, Devlin B, et al. (2011) Testing for an unusual distribution of rare variants. PLoS Genet 7:e1001322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. San Lucas FA, Wang G, Scheet P, Peng B (2012) Integrated annotation and analysis of genetic variants from next-generation sequencing studies with variant tools. Bioinformatics 28:421–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Oligonucleotides and PCR conditions for high resolution melting assays.

(DOC)

Oligonucleotides and PCR conditions for SNP genotyping.

(DOC)

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that all data underlying the findings are fully available without restriction. All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.