Abstract

The total culturable virus assay (TCVA) and an integrated cell culture-PCR (ICC-PCR) were compared in parallel to evaluate their detection reliability. Source, finished, and tap water samples from three drinking water treatment plant systems were analyzed by TCVA, and every cell culture dish was subsequently examined by reverse transcription (RT) multiplex PCR using enterovirus- and adenovirus-specific primers. Twenty-seven of 180 (15%) inoculated dishes exhibited cytopathic effects (CPE). Virus concentrations for source water ranged from 3.3 to 21.0 most probable numbers of infectious units (MPN) per 100 liters. No finished or tap water samples were positive. On the other hand, 38 (21%) of the dishes were positive in multiplex ICC-PCR. Virus concentrations ranged from 4.5 to 10.2 MPN/100 liters for source water and 0 to 0.9 MPN/100 liters for finished and tap water. In spite of its superior sensitivity, the ICC-PCR assay resulted in lower virus concentration values than the TCVA for two of the source water sites. Retest of the CPE-positive dishes using reovirus-specific RT-PCR revealed that 24 of the 27 (89%) dishes were also positive for reoviruses. These observations suggested that the detection reliability of ICC-PCR is restricted by the primer sets that are integrated in the reaction mixture. The observation of an uneven distribution of PCR-positive culture dishes in a given sample raises an additional caution that simple extrapolation of the ICC-PCR result from the analysis of a limited fraction of collected samples should be avoided to minimize possible over- and underestimation of the amount of virus.

Enteric viruses that are important causative agents of human diseases (24) include the enteroviruses, rotaviruses, noroviruses (formerly called Norwalk-like viruses or small round structured virus), adenoviruses, reoviruses, and others. They are excreted in feces of infected individuals in high numbers and are transmitted via the fecal-oral route mainly through contaminated water, food, and soil. The presence of enteric viruses in water may cause a health risk. Because they are highly stable in water (19) and are not completely eliminated by the drinking water treatment process under certain conditions (12), periodic monitoring may be needed to show whether viruses contaminate treated drinking water. A number of previous studies have examined source and treated water for enteric viruses. Enteroviruses and adenoviruses have been frequently found (6, 12, 14, 17). Other enteric viruses were also found in environmental waters, such as hepatitis A virus (27), astroviruses (6), noroviruses (3, 16), and reoviruses (20, 28). Reoviruses have often been detected either alone or associated with enteroviruses and may interfere with the propagation of the enterovirus in cell culture (21).

Historically, the standard method for isolation of human enteric viruses from environmental water samples involves the ability of viruses to produce observable cytopathic effects (CPE) in animal cell cultures. A widely used example of one of these methods is the total culturable virus assay (TCVA) that was used for a national occurrence study of waterborne viruses in the United States (10). The TCVA is optimized for detection and quantification of enteric viruses that can replicate in cell culture, but the experimental procedure of the assay is labor intensive and time-consuming. Also, some enteric viruses, such as the noroviruses, cannot be cultured and others, such as rotaviruses and hepatitis A virus, are difficult to cultivate in cell culture systems. Compared to cell culture techniques, the application of reverse transcription (RT)-PCR assays that target virus genetic material can detect nonculturable viruses and viruses that are difficult to cultivate, reduce the assay time and cost, and increase detection sensitivity (1, 7, 9, 20, 23). However, various inhibitory factors from an environmental sample can interfere with the PCR assay. In addition, PCR is often unable to discriminate between infectious and inactivated virus (26). Indeed, viruses that have been inactivated by UV light, heat, or hypochlorite have often yielded positive PCR results in previous studies (4, 11, 22). Integrated cell culture-PCR (ICC-PCR) procedures and virus detection by cell culture followed by RT-PCR may exclude nucleic acid amplification from inactivated virus (8, 17, 25). ICC-PCR should increase the detection sensitivity as well via replication and amplification of a very limited number of infectious virions (6, 14). Second-round amplification by nested or seminested PCR has been suggested to contribute higher detection sensitivity and specificity to ICC-PCR (13). However, the usefulness of ICC-PCR for virus occurrence studies of environmental samples with respect to quantification has been in question.

The objective of this study was to evaluate the detection reliability of TCVA and ICC-PCR with environmental water samples. The standard TCVA procedure was employed to detect and quantify infectious viruses in the environmental samples. We primarily employed enterovirus- and adenovirus-specific multiplex RT-PCR for this study since these two virus groups have been major targets for PCR-based assays. All cell culture dishes used in the TCVA were subjected to the ICC-PCR, and the most probable numbers (MPN) of virus in the samples for both assays were calculated by the same computational flow to compare their quantitative aspects directly.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viruses and cells.

Sabin poliovirus type 3 and adenovirus type 5 were provided by the Korean National Institute of Health, and reovirus type 1 was obtained from the College of Veterinary Medicine, Kunkook University, Seoul, South Korea. The viruses were propagated in Buffalo green monkey kidney (BGM) cells and were used as positive controls for cell culture and PCR. BGM cells were grown in blended growth medium of Eagle minimum essential medium with Hanks salts (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) and Leibovitz's L-15 medium (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Gibco BRL), penicillin-streptomycin (100 U/ml and 100 μg/ml, respectively), and 9 mM NaHCO3 at 37°C and 5% CO2. The maintenance medium contained 12.5 μg of tetracycline hydrochloride/ml and 1 mg of amphotericin B/ml in addition to the growth medium formula and was supplemented with 3% fetal bovine serum.

Collection and concentration of environmental water samples.

Three areas were chosen randomly, and source water (rivers or lakes), finished water after the complete treatment process of sedimentation, filtration, and chlorination, and household tap water samples were collected from each area. Approximately 200-liter (for source water) or 1,500-liter (for finished and tap water) water samples were filtered through 1MDS filters (Cuno, Meriden, Conn.), and viruses were eluted and concentrated according to TCVA procedures (10). Briefly, viruses were eluted from the filters with 1.5% beef extract (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, Md.) (pH 9.4) containing 0.05 M glycine and concentrated by organic flocculation. Concentrated samples were suspended in 0.15 M sodium phosphate (pH 9.4). After centrifugation, the pH of supernatants was adjusted to 7.0 to 7.4. Each final concentrated sample was divided into two subsamples and used for inoculation or stored at −70°C for later use.

Cell culture assay.

BGM cells between passages 130 and 150 were grown in 21-cm2 tissue culture dishes until they produced confluent monolayers on growth medium. An appropriate portion of the final concentrate (<40 μl/cm2) was inoculated into each of 20 culture dishes divided as two sets of subsamples. After 90 min of adsorption, the culture dishes were overlaid with maintenance medium and incubated at 37°C for 14 days. The cultures were refed with fresh maintenance medium at day 7 postinoculation. All of the samples underwent secondary passages on fresh monolayers of BGM cells. Cultures showing CPE on more than 75% of the cell monolayers in the second passage were harvested and lysed for nucleic acid extraction. All other samples were lysed on day 14 of the second passage, including uninfected controls. When CPE developed only in the second passage, cultures were subjected to a third passage along with uninfected controls. Cultures that developed CPE in both the first and second passages or in both the second and third passages were scored as positive. The total number of confirmed positive cultures was entered into an MPN computation program (the MPNV program can be downloaded at www.epa.gov/microbes) to calculate the MPN/100-liter values and confidence limits.

Nucleic acid extraction.

For ICC-PCR, nucleic acid extracts were prepared from samples with and without CPE. Cell monolayers were washed in cold phosphate-buffered saline and then lysed with lysis buffer (50 mM sodium acetate [pH 5.2], 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 1 mM EDTA, 50 μg of proteinase K/ml). Lysates were incubated at 56°C for 10 min, and then nucleic acid was purified by phenol-chloroform extraction and precipitated with ethanol. The nucleic acid was suspended in 20 μl of RNase-free distilled H2O and subjected to RT immediately.

RT

The RT reaction was carried out by using random hexamers (Promega, Madison, Wis.). Prior to the reaction, 20 μl of nucleic acid was heated at 95°C for 2 min with 0.5 μg of random hexamers and then chilled on ice immediately. Heat-denatured nucleic acid was mixed with a 0.5 mM concentration of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, reaction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3], 75 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 10 mM dithiothreitol), and 200 U of Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Promega). Finally, 30 μl of reaction mixture was incubated at 37°C for 30 min and 42°C for 1 h. The reverse transcriptase was inactivated at 95°C for 5 min after the reaction.

PCR.

Enterovirus- and adenovirus-specific primers were prepared based on sequences reported previously (2, 18). First-round PCR was carried out by the multiplex strategy (7). Ten microliters of RT reaction product was mixed with 90 μl of the PCR mixture, containing reaction buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3], 1.5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl), a 0.5 mM concentration of each dinucleoside triphosphate, 25 pmol of each enterovirus primer (5′-CAA GCA CTT CTG TTT CCC CGG-3′, positions 164 to 184; and 5′-ATT GTC ACC ATA AGC AGC CA-3′, positions 599 to 578), 10 pmol of the adenovirus primer (5′-GCC GCA GTG GTC TTA CAT GCA CAT C-3′, positions 18858 to 18883; and 5′-CAG CAC GCC GCG GAT GTC AAA GT-3′, positions 19136 to 19158), and 1 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Roche, Indianapolis, Ind.). The amplification was carried out for 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min after initial denaturation at 94°C for 4 min. A final extension step was performed at 72°C for 7 min. For higher sensitivity and specificity, a second-round PCR was performed. One microliter of first-round PCR product was added to 49 μl of reaction mixture, which contained 10 pmol of seminested enterovirus primer (5′-CAA GCA CTT CTG TTT CCC CGG-3′, positions 164 to 184; and 5′-CTT GCG CGT TAC GAC-3′, positions 526 to 511) or nested adenovirus primer (5′-GCC ACC GAG ACG TAC TTC AGC CTG-3′, positions 18937 to 18960; and 5′-TTG TAC GAG TAC GCG GTA TCC TCG CGG TC-3′, positions 19051 to 19079). Cycle conditions were identical to those of the first-round amplification. Final products were analyzed by electrophoresis on 1.8% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide and UV transillumination. Positive PCR results were determined by visualization of specific band products (362 bp for enterovirus and 142 bp for adenovirus), and the MPN values were calculated the same way as for the TCVA.

RT-PCR for reovirus.

Fresh BGM cell monolayers were inoculated with supernatants of CPE-positive cultures, and intracellular RNA was extracted 2 days postinoculation as described above. The RT reaction was performed as described above except that the denaturation step was carried out at 95°C for 10 min. The PCR primers and reaction conditions for reovirus detection were identical to those described previously (28). Amplified products were separated electrophoretically on a 1.8% agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

Quality control.

To reduce the number of false positives resulting from carryover contamination of amplified virus particles or viral nucleic acid, separate areas and equipment were used for each stage of the process. In order to qualify the sample processing and cell culture assay, quality control and performance evaluation samples were tested under the supervision of the Korean National Institute of Environmental Research according to a virus monitoring protocol (10). Negative controls (cultures inoculated with only 0.15 M sodium phosphate [pH 7.4]) and positive controls (cultures inoculated with poliovirus type 3 that was diluted in 0.15 M sodium phosphate) were included with each set of test samples. These controls were taken through nucleic acid extraction and the RT-PCR assay. Additional blank controls for PCR (containing the same reaction mixture except for the nucleic acid template) were incorporated with all PCR assays.

RESULTS

Cell culture analysis.

A total of nine samples were analyzed by the TCVA. CPE-positive cultures were isolated from the source water from all three areas. Overall, 27 of the 180 culture dishes (15%) exhibited CPE (Table 1). None of the cell culture dishes which were inoculated with the finished or tap water samples developed observable CPE (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Detection of enteric viruses by TCVA in source, finished, and tap water samples

| Site and sample | Detection of enteric viruses ina:

|

Total | MPN/100 litersb | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subsample 1

|

Subsample 2

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |||

| Area I | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | 11 | 16.0 (7.5-26.8)c |

| Finished | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | 0 | 0.0 |

| Tap | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | 0 | 0.0 |

| Area II | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | 13 | 21.0 (10.7-34.6) |

| Finished | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | 0 | 0.0 |

| Tap | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | 0 | 0.0 |

| Area III | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | 3 | 3.3 (1.8-7.4) |

| Finished | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | 0 | 0.0 |

| Tap | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | 0 | 0.0 |

Both subsamples 1 and 2 were derived from the same final concentrated sample. Equal portions of each subsample were inoculated into 10 culture dishes.

MPN was calculated by using the MPNV software program supplied by the Environmental Protection Agency.

The ranges in parentheses are 95% confidence limits.

ICC-PCR analysis.

All cell culture dishes analyzed by the TCVA were also subjected to the ICC-PCR analysis for enterovirus and adenovirus. Overall, 38 of 180 dishes (21%) were PCR positive. Twenty-two of 38 dishes were positive for enterovirus, and 24 dishes were positive for adenovirus. Eight of 38 dishes were positive for both enterovirus and adenovirus (Table 2). While CPE-positive cultures were isolated only from source water samples from areas I through III, the ICC-PCR detected viral RNA in finished and tap water samples from areas I and II. Both finished and tap water samples from area III were PCR negative.

TABLE 2.

Detection of enteroviruses and adenoviruses by multiplex ICC-PCR

| Site | Detection of enteroviruses and adenoviruses ina:

|

Total | MPN/100 liters | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subsample 1

|

Subsample 2

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |||

| Area I | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source | A | E | A | − | − | − | A | A | − | − | − | − | − | − | E | − | − | A | E | − | 8 | 10.2 (4.0-18.2) |

| Finished | A | − | A | − | A | − | − | − | − | − | E | − | − | − | − | − | E | − | B | B | 7 | 0.9 (0.3-1.6) |

| Tap | E | − | A | − | − | A | − | A | − | − | A | − | − | A | − | − | − | − | A | − | 7 | 0.9 (0.3-1.6) |

| Area II | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source | − | B | B | − | B | − | − | B | − | − | − | − | − | E | − | A | E | E | − | − | 8 | 10.2 (4.0-18.2) |

| Finished | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | E | − | − | − | − | − | − | B | − | E | 3 | 0.3 (0.0-0.7) |

| Tap | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | E | − | − | − | − | − | − | 1 | 0.1 (0.0-0.3) |

| Area III | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | E | − | B | E | − | − | − | − | A | − | − | − | 4 | 4.5 (0.8-9.4) |

| Finished | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | 0 | 0.0 |

| Tap | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | 0 | 0.0 |

−, negative; A, sole detection of adenovirus; E, sole detection of enterovirus; B, dual detection of both enterovirus and adenovirus in a given dish.

The results of the TCVA and ICC-PCR assay did not correspond well. The MPN/100-liter values obtained in the ICC-PCR assay for source water samples from areas I and II were lower than those of the TCVA. Significant numbers of culture dishes inoculated with finished and tap water samples from areas I and II were PCR positive, while the dishes were scored CPE negative in TCVA (Tables 1 and 2).

RT-PCR for reovirus.

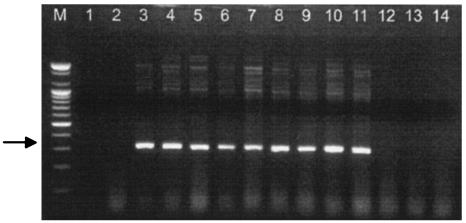

One type of discrepancy in the quantitative results for source water samples from areas I and II between the TCVA and ICC-PCR assay was culture dishes showing PCR-negative results when they were CPE positive in the TCVA. To test whether this discrepancy was due to detection of reoviruses, all 27 CPE-positive culture dishes were subjected to the reovirus-specific RT-PCR. Twenty-four of the 27 culture dishes (89%) produced reovirus-specific 320-bp amplified PCR products (Table 3). All reovirus-positive culture dishes in this PCR were from areas I and II, and there was no amplified product in samples from area III (Fig. 1). The PCR products were confirmed to be reovirus specific by direct sequencing (data not shown).

TABLE 3.

Detection of reoviruses in CPE-positive cultures by ICC-PCR

| Sitea | Detection of reoviruses inb:

|

Total | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subsample 1

|

Subsample 2

|

||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||

| Area I | +/R | +/R | − | − | − | − | +/R | − | − | − | +/R | +/R | +/R | +/R | +/R | +/R | − | − | +/R | +/R | 11/11 |

| Area II | +/R | +/R | +/R | +/R | +/R | − | − | +/R | − | +/R | +/R | − | +/R | − | +/R | +/R | +/R | − | − | +/R | 13/13 |

| Area III | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | +/N | − | +/N | +/N | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | 3/0 |

CPE positive cultures identified only in source water samples of each area.

−, CPE negative cultures; +/R, reovirus positive in CPE-positive cultures; +/N, reovirus negative in CPE-positive cultures.

FIG. 1.

Reovirus-specific RT-PCR results for culture dishes CPE positive in TCVA. Culture supernatants from dishes CPE positive in TCVA were inoculated onto fresh BGM cells, and intracellular nucleic acid was extracted at the 2 days postinoculation. Following RT-PCR, products were separated electrophoretically on a 1.8% agarose gel. The expected size of the PCR product is 320 bp (arrow). Lanes: M, 100-bp DNA ladder size marker; 1, PCR-negative control; 2, mock-infected cell; 3, positive control (reovirus type 1); 4 to 7 and 8 to11, representative culture dishes for samples from areas I and II, respectively; 12 to14, three culture dishes CPE positive for area III source water samples.

DISCUSSION

When conducting a virus occurrence study of environmental samples, it is important to know the advantages and disadvantages of the detection method. The TCVA is a standardized and validated method for the detection and quantification of various culturable viruses (10). Meanwhile, the ICC-PCR method has been introduced in an attempt to compensate for several disadvantages in the TCVA, such as the time-consuming cell culture process and the limited detection sensitivity (25). That ICC-PCR has superior sensitivity in the detection of a given virus through nucleic acid amplification has been well recognized, but its applicability to practical monitoring with environmental samples is yet to be evaluated. In this study, for the first time, the detection sensitivities of the TCVA and ICC-PCR were compared in parallel and the overall reliability of the detection results was analyzed. To avoid any unintended carryover contamination, a strict control strategy for each procedure was applied to both the TCVA and ICC-PCR assay.

In the analysis by TCVA three of nine water samples (33%) yielded positive results. These were all source water samples that were collected from either rivers (areas I and III) or a lake (area II). On the other hand, seven of nine samples (78%), including finished and tap water samples that were negative by TCVA, were positive by nested (or seminested) ICC-PCR. This inconsistency seemed to be caused by the difference in the detection sensitivities of the two methods. Positive scoring in TCVA depends on visual determination of CPE, which was identified as cell disintegration or as changes in cell morphology (10). Therefore, it might be difficult to detect CPE when the samples contained very low numbers of culturable viruses or viruses that replicate poorly in the BGM cell cultures used. For example, a number of coxsackievirus A serotypes do not produce CPE in BGM cells (24).

Thirty-five of 38 ICC-PCR positive culture dishes (92%) produced visible specific bands only after second-round nested or seminested PCR. After first-round PCR only three culture dishes were identified as PCR positive. This suggests that the nested or seminested amplification step increases the detection sensitivity of ICC-PCR. In previous studies, nested PCR assays have also resulted in a much higher detection efficiency for viruses than the single-round PCR assay with environmental water samples (6, 13).

Despite the superior detection sensitivity of ICC-PCR, a number of CPE-positive culture dishes from source water samples from areas I and II were negative for both enterovirus and adenovirus. Thus, it seemed that the cell culture method could be more sensitive than the ICC-PCR assay based on the higher MPN/100-liter values in the TCVA for certain water samples. This problem was solved by the demonstration of the presence of reovirus in the culture dishes. When the reovirus-specific detection results in the ICC-PCR analysis was combined with the enterovirus and adenovirus results, the MPN/100-liter values for the source water samples from areas I and II increased from 10.2 and 10.2 to 24.1 and 27.7, respectively. This result suggests that, before the ICC-PCR can be applied to practical, widespread monitoring studies, a multiplex PCR strategy needs to be developed that can detect various virus groups simultaneously in the given samples.

Previous studies have shown that reoviruses are very common in environmental water (21, 28). Some studies have suggested that reovirus can interfere with enterovirus replication when the concentration of reovirus is much higher than that of enterovirus (21), but enteroviruses and reoviruses have been found often in the same samples (Table 4; 20).

TABLE 4.

Enterovirus, adenovirus, and reovirus detection results by ICC-PCR for CPE-positive culture dishes in TCVA

| Virus(es) | No. of positive dishes (%) |

|---|---|

| Reovirus | 13 (48.2) |

| Enterovirus | 2 (7.4) |

| Enterovirus + adenovirus | 1 (3.7) |

| Reovirus + enterovirus | 4 (14.8) |

| Reovirus + adenovirus | 3 (11.1) |

| Reovirus + enterovirus + adenovirus | 4 (14.8) |

Adenovirus was detected alone or with the two other virus groups in many samples in ICC-PCR analysis (Tables 2 and 4). It is very difficult to cultivate adenovirus in BGM cells (5), as adenovirus grows in cells much more slowly than enterovirus and reovirus (15, 29). Nevertheless, there have been several reports of detection of adenoviruses in water by the ICC-PCR technique (6, 17). In fact, BGM cells infected with approximately 1,000 PFU of adenovirus type 5 failed to develop observable CPE but yielded positive results by ICC-PCR (data not shown). These results suggest that adenovirus might not be detected by cell culture assay even though there is a high number of the virus in a water sample.

Taken together, ICC-PCR demonstrated its superior detection sensitivity for given viruses in comparison to TCVA, so that ICC-PCR would be an excellent option to study virus occurrence in water samples. The usefulness of a given method for environmental monitoring, however, depends on two factors: higher detection sensitivity and appropriateness of quantification. Even though ICC-PCR could be an excellent strategy to determine the presence or absence of virus, simple extrapolation of the detection results using a limited fraction of collected sample may over- or underestimate the amount of virus. Uneven distribution of PCR-positive culture dishes in ICC-PCR analysis supports this concern (Table 2). In addition, the higher detection sensitivity of the ICC-PCR strategy often depends on the availability of specific primers for targeted viruses. TCVA and ICC-PCR, the two methods for the study of virus occurrence being examined, harbor inherent advantages and disadvantages. Therefore, selective application of these methods for an intended study should maximize the usefulness of the given method. A prerequisite for developing the ICC-PCR method beyond current limitations in environmental sample monitoring is to develop tools for the reliable quantification of ICC-PCR results, including the development of diverse multiplex PCR primer sets that function well with samples demonstrating various water qualities and characteristics.

Acknowledgments

We thank G. S. Fout of the Environmental Protection Agency for critical review. We are also indebted to K. T. Rhie at Kyung Hee University for excellent technical assistance in sample collection.

This work was supported by the Korean National Institute of Environmental Research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbaszadegan, M., P. Stewart, and M. LeChevallier. 1999. A strategy for detection of viruses in groundwater by PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:444-449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allard, A., B. Albinson, and G. Wadell. 1992. Detection of adenoviruses in stools from healthy persons and patients with diarrhea by two-step polymerase chain reaction. J. Med. Virol. 37:149-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson, A. D., A. G. Heryford, J. P. Sarisky, C. Higgins, S. S. Monroe, R. S. Beard, C. M. Newport, J. L. Cashdollar, G. S. Fout, D. E. Robbins, S. A. Seys, K. L. Musgrave, C. Medus, J. Vinje, J. S. Bresee, H. M. Mainzer, and R. I. Glass. 2003. A waterborne outbreak of Norwalk-like virus among snowmobilers—Wyoming, 2001. J. Infect. Dis. 187:303-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blackmer, F., K. A. Reynolds, C. P. Gerba, and I. L. Pepper. 2000. Use of integrated cell culture-PCR to evaluate the effectiveness of poliovirus inactivation by chlorine. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:2267-2268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown, M., H. L. Wilson-Friesen, and F. Doane. 1992. A block in release of progeny virus and a high particle-to-infectious unit ratio contribute to poor growth of enteric adenovirus types 40 and 41 in cell culture. J. Virol. 66:3198-3205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chapron, C. D., N. A. Ballester, J. H. Fontaine, C. N. Frades, and A. B. Margolin. 2000. Detection of astroviruses, enteroviruses, and adenovirus types 40 and 41 in surface water collected and evaluated by the information collection rule and an integrated cell culture-nested PCR procedure. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:2520-2525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cho, H. B., S. H. Lee, J. C. Cho, and S. J. Kim. 2000. Detection of adenoviruses and enteroviruses in tap water and river water by reverse transcription multiplex PCR. Can. J. Microbiol. 46:417-424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cho, Y. H., and C. H. Lee. 2002. Detection of poliovirus in water by cell culture and PCR methods. Kor. J. Microbiol. 38:198-204. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fout, G. S., B. C. Martinson, M. W. Moyer, and D. R. Dahling. 2003. A multiplex reverse transcription-PCR method for detection of human enteric viruses in groundwater. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:3158-3164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fout, G. S., F. W. Schaefer III, J. W. Messer, D. R. Dahling, and R. E. Stetler. 1996. ICR microbial laboratory manual. Publication no. EPA/600/R-95/178. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, D.C.

- 11.Gerba, C. P., D. M. Gramos, and N. Nwachuku. 2002. Comparative inactivation of enteroviruses and adenovirus 2 by UV light. J. Appl. Microbiol. 68:5167-5169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilgen, M., B. Wegmüller, P. Burkhalter, H. P. Bühler, U. Müller, J. Lüthy, and U. Candrian. 1995. Reverse transcription PCR to detect enteroviruses in surface water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:1226-1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Green, J., K. Henshilwood, C. I. Gallimore, D. W. G. Brown, and D. N. Lees. 1998. A nested reverse transcriptase PCR assay for detection of small round-structured viruses in environmentally contaminated molluscan shellfish. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:858-863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greening, G. E., J. Hewitt, and G. D. Lewis. 2002. Evaluation of integrated cell culture-PCR (C-PCR) for virological analysis of environmental samples. J. Appl. Microbiol. 93:745-750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Irving, L. G., and F. A. Smith. 1981. One-year survey of enteroviruses, adenoviruses, and reoviruses isolated from effluent at an activated-sludge purification plant. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 41:51-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kukkula, M., L. Maunula, E. Silvennoinen, and C. H. von Bonsdorff. 1999. Outbreak of viral gastroenteritis due to drinking water contaminated by Norwalk-like viruses. J. Infect. Dis. 180:1771-1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee, S. H., and S. J. Kim. 2002. Detection of infectious enteroviruses and adenoviruses in tap water in urban areas in Korea. Water Res. 36:248-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leparc, I., M. Aymard, and F. Fuchs. 1994. Acute, chronic and persistent enterovirus and poliovirus infection: detection of viral genome by semi-nested PCR amplification in culture-negative samples. Mol. Cell. Probe 8:487-495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moore, B. E. 1993. Survival of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), HIV-infected lymphocytes, and poliovirus in water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:1437-1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muscillo, M., A. Carducci, G. La Rosa, L. Cantiani, and C. Marianelli. 1997. Enteric virus detection in Adriatic seawater by cell culture, polymerase chain reaction and polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Water Res. 31:1980-1984. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muscillo, M., G. La Rosa, C. Marianelli, S. Zaniratti, M. R. Capobianchi, L. Cantiani, and A. Carducci. 2001. A new RT-PCR method for the identification of reoviruses in seawater samples. Water Res. 35:548-556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nuanualsuwan, S., and D. O. Cliver. 2002. Pretreatment to avoid positive RT-PCR results with inactivated viruses. J. Virol. Methods 104:217-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oberste, M. S., K. Maher, M. R. Flemister, G. Marchetti, D. R. Kilpatrick, and M. A. Pallansch. 2000. Comparison of classic and molecular approaches for the identification of untypeable enteroviruses. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1170-1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pallansch, M. A., and R. P. Roos. 2001. Enteroviruses: polioviruses, coxsackieviruses, echoviruses, and newer enteroviruses, p. 723-775. In B. N. Fields (ed.), Virology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 25.Reynolds, K. A., C. P. Gerba, and I. L. Pepper. 1996. Detection of infectious enteroviruses by an integrated cell culture-PCR procedure. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:1424-1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richards, G. P. 1999. Limitation of molecular biological techniques for assessing the virological safety of foods. J. Food Prot. 62:691-697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwab, K. J., R. De Leon, and M. D. Sobsey. 1995. Concentration and purification of beef extract mock eluates from water samples for the detection of enteroviruses, hepatitis A virus, and Norwalk virus by reverse transcription-PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:531-537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spinner, M. L., and G. D. Di Giovanni. 2001. Detection and identification of mammalian reoviruses in surface water by combined cell culture and reverse transcription-PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:3016-3020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tani, N., Y. Dohi, N. Kurumatani, and K. Yonemasu. 1995. Seasonal distribution of adenoviruses, enteroviruses and reoviruses in urban river water. Microbiol. Immunol. 39:577-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]