Abstract

Objective:

To identify CT findings of massive venous invasion (MVI) in colorectal cancer, compare them to pathological findings and evaluate its clinical implications.

Methods:

Among 423 patients who received surgical resection of colorectal cancer, pre-operative CT of 26 patients (15 males, 11 females; mean age, 63.0 ± 12.1 years) with histopathologially proven MVI and 26 patients (14 males, 12 females; mean age, 71.1 ± 9.6 years) with histopathologically proven lymph node (LN) metastases were reviewed and compared with histopathological findings. We evaluated CT detectability of MVI and the morphologic differences between MVI and LN metastasis. All cases were followed up for at least 6 months after surgery.

Results:

Pre-operative CT correctly diagnosed only one case as tumour thrombus. 9 lesions were not detected on CT, and others were misdiagnosed pre-operatively as regional LN metastasis (14 cases) and juxtatumoural abscess (2 cases). After reviewing these cases, MVIs were identifiable in 20 of 26 cases. MVI was depicted on CT as nodules (oval, lobulated), abscess-like or intravenous tumour thrombus. MVI was significantly larger than LN metastasis (p < 0.05), while contrast enhancement was significantly lower (p < 0.05), and MVI often had an enhanced rim. Ten patients had synchronous metastases, and six patients had metachronous distant metastases within 5 years.

Conclusion:

Many cases of MVI were distinguishable from LN metastases on pre-operative CT of colorectal cancer, but their appearances were varied, reflecting their histopathological behaviours. The distant metastatic rate was much higher in cases with MVI.

Advances in knowledge:

Radiologists should be aware of CT findings of MVI in colorectal cancer as a sentinel sign of distant metastasis.

Radiological staging is indispensable for the management of colorectal cancer. The TNM classification is a worldwide method for the staging.1,2 Surgical resection is the primary treatment modality for colorectal cancer, and post-operative patient management is based on the pathological assessment [pathological TNM stage (pTNM)] of the post-operative specimen. Venous invasion by tumour has been demonstrated pathologically to have significant adverse impact on outcome.3–15 Special techniques such as immunohistochemical staining of endothelium or elastic fibre stains of venous walls may increase the accuracy of venous invasion grade. Currently, no widely accepted standards or guidelines for the pathological evaluation of vessel invasion exist, so pathology sampling practices may vary widely at both individual and institutional levels.3 The College of American Pathologists, Northfield, IL, recommend that at least three blocks (optimally, five blocks) of tumour at its point of deepest extent should be submitted for microscopic examination,3,4 and that in reports, the following method should be used: VX, not assessed; V0, negative for tumour; V1, positive for tumour; V1a, inside venous wall; V1b, outside venous wall; V1a,b, both inside and outside venous wall.5 In Japan, according to the general rules for clinical and pathological studies on cancer of the colon and rectum, venous invasion is classified into four groups [v0 (none), v1 (minimal), v2 (intermediate) and v3 (massive)].16,17 Massive venous invasion (MVI) is an indication for post-operative adjuvant chemotherapy after curative operation for Stage II colorectal cancer. High-risk factors in Stage II colorectal cancer are: T4, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma/undifferentiated carcinoma, vascular invasion, lymphatic vessel invasion, perineural invasion, obstruction or tumour perforation at initial presentation, ≤12 regional lymph nodes (LNs) examined and high carcinoembryonic antigen level.18,19

CT is the main radiological examination for local and distant extension (i.e. clinical TNM stage) of colorectal cancer. Several reports have described CT appearances of tumour invasion in large veins such as the vena cava and the portal vein and their tributaries.20,21 However, only one report described CT-pathological correlation of venous invasion in small- or medium-sized veins.22 In that report, the interobserver agreement for CT detection of venous invasion was poor, and the architecture of the vessel wall did not seem to be confirmed pathologically by additional special staining such as Elastica van Gieson stain (EVG). We thought that the agreement between radiologists was limited by poor understanding of the histology of MVI in colorectal cancer. Studies on venous invasion with MRI have also been reported,23,24 but the field of view was restricted to the rectum and sigmoid colon because endorectal coils were used. The venous invasions detected by MRI in these studies were continuous to the primary lesion that was regarded as extramural lesions. CT findings of tumour invasion as discrete mass lesions have not previously been well documented to the best of our knowledge.

The objectives of this study were to investigate CT detectability of MVI in small- or medium-sized veins by comparing CT findings with the histology of resected surgical specimens and to assess the clinical significance of pre-operative detection of MVI on CT.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Patients

This retrospective study was approved by the institutional review board of Gunma Central Hospital, Maebashi, Japan, and informed consent was waived. Among 423 patients who received surgical resection of colorectal cancer from August 2009 to November 2013 in our hospital, 26 patients [15 males and 11 females, ages ranging from 42 to 84 years (mean ± standard deviation, 63.0 ± 12.1 years)] were histopathologically proven to have MVI were selected as a MVI group. During the same period in our hospital, an additional 26 patients [14 males and 12 females, ages ranging from 55 to 86 years (mean ± standard deviation, 71.1 ± 9.6 years)] with LN metastases and no or minimal venous invasion were also selected as a confirmed LN metastasis group (LN group). Minimal venous invasion meant that tumours were restricted to small microscopic veins. This should mean that in the LN group, any nodular lesions detectable on CT should be genuine LN and not MVI. Owing to the small population size, we were not able to perform matching of sex, age or clinical disease stage between the MVI group and LN group. CT was obtained within 2 weeks prior to surgery. Adjuvant chemotherapy was applied to Stage III and high-risk Stage II within 2 months after surgery, considering patients' activity of daily living, age, liver and renal function, and wish to undergo adjuvant chemotherapy. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy was not applied to patients in this study. All cases were also prospectively followed up for at least 6 months by CT examination from August 2009 to April 2014.

CT protocol

A 64-detector row CT scanner (LightSpeed VCT®; GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI) was used for this study. All patients were placed in the supine position on the CT table. Non-enhanced images from the upper abdomen to the pelvis were obtained. Intravenous injection of 2 ml kg−1 of non-ionic contrast agent (Iopamiron 300; Bayer-Schering, Berlin, Germany) was performed as follows: half of the contrast agent was injected at a rate of 0.5 ml s−1, after the end of the first half of the injection, there was a pause of 1 min and 30 s, and then, the remaining half of the contrast agent was injected at a rate of 1.5 ml s−1. Enhanced images from the chest to the pelvis were subsequently obtained without interval. This CT protocol was unusual but routine in our hospital. The first half of the injection enables evaluation of the entire urinary tract, and the second half of the injection enables evaluation of the vessels and abdominal viscera, especially the liver. This protocol has a smaller radiation dose than that of dynamic contrast-enhanced CT. CT acquisition was performed with a section width of 5 mm and reconstruction increment of 1 mm. CT images consisted transverse images and multiplanar reformations (MPRs). Three cases had only transverse images owing to the lack of electronic records.

Image analysis

Two radiologists retrospectively individually evaluated the appearance of MVI and LN on CT, referring to pathological reports and pre-operative CT reports. In examining CT images, they were blinded to histopathological images and morphological patterns and precise locations on CT of MVIs and LN metastases, but they were not blinded to pathological reports and pre-operative CT reports.

One of two radiologists had 5 years' experience in abdominal CT and the other had more than 30 years. They evaluated CT images for lesions consistent in location and size with MVI lesions and LN on the en bloc surgical specimens. Differences in assessment were resolved by consensus. After evaluating CT detectability of the MVI and LN lesions, they evaluated the location, image pattern, size and contrast enhancement of the lesions. Image patterns were defined as follows: “Oval pattern” was a round- or oval-shaped nodule with a smooth margin. “Lobulated pattern” was a nodule with irregular margins and microprojections. “Abscess-like pattern” was an ill-defined mass with a hypodense centre and peripheral enhancement. “Intravenous tumour thrombus” pattern was a long and narrow solid lesion in a venous lumen, with a long axis following the vessel axis. Enhanced rim was a lesion's contrast-enhanced margin. For the evaluation of contrast enhancement, a round or oval region of interest that was as large as possible, but not including the margin, was placed in the lesion. The CT number of the enhanced image was subtracted from that of the unenhanced CT. The image pattern and contrast enhancement of MVI lesions and LN metastases were then compared.

CT-pathological correlation

One pathologist with 24 years' experience in surgical pathology of gastrointestinal cancers evaluated the detailed histopathological structure of the lesions, using EVG stain25,26 to confirm the relationship between the tumour and the venous wall, in addition to the usual haematoxylin and eosin stain. After identifying the location of MVI and LN metastasis on CT, the radiologists informed the pathologist of their locations and appearances on CT images. The pathologist selected appropriate blocks and reviewed the specimens again to analyse the histopathological bases reflected by the CT findings, processing new sections of the area of interest when necessary.

Statistical analysis

We used the Shapiro–Wilk test to verify sampled data of size and contrast enhancement on both MVI and LN metastasis. We then statistically evaluated the differences between MVI and LN metastasis for size and contrast enhancement, using Wilcoxon rank sum test or Welch two-sample t-test according to their normality. We classified the morphological patterns of MVI and LN metastases and then evaluated the spectrum of morphological patterns of MVI and the LN metastasis by Fisher's exact test. In the follow-up study, we searched for synchronous and metachronous metastatic sites and counted their frequencies on patients with MVI and the LN group, and then evaluated the distributions of the metastatic sites and their frequency by Fisher's exact test.

RESULTS

Final histopathological staging (pTNM) of the patients with MVI are listed in Table 1. All MVIs were confirmed by EVG stain. The radiologists retrospectively blindly reviewed the CTs and detected MVI on pre-operative CT in 20 of 26 patients. Among these 20 cases, pre-operative CT diagnosis was correct in only one case, when tumour thrombus pattern in the inferior mesenteric vein (IMV) was correctly identified as such. Other cases were misdiagnosed as LN metastasis (14 cases) and juxtatumoural abscess (2 cases). In post-operative reviewing, a total of 31 MVIs were detected on CT from 26 patients, and 45 LNs were detected from 26 patients of the LN group. From the LN group, two nodules were detected that were not classifiable into LN metastasis or MVI.

Table 1.

Population and their clinical and histopathological diagnosis

| Case | Age (years) | Sex | Location | cTNM and venous invasion | pTNM and venous invasion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 70 | F | Rectum | cT4aN0M0, v3 | pT4aN0, v3 |

| 2 | 82 | M | Ascending colon | cT3N0M0 | pT3N0, v3 |

| 3 | 66 | M | Caecum | cT4aN1M1 | pT4aN0, v3 |

| 4 | 53 | F | Rectum | cT4aN1M1 | pT3N0, v3 |

| 5 | 45 | M | Rectum | cT3N2M0 | pT3N0, v3 |

| 6 | 63 | M | Rectum | cT4aN1M1 | pT4bN0, v3 |

| 7 | 66 | M | Rectum | cT4aN1M0 | pT3N1, v3 |

| 8 | 42 | M | Sigmoid colon | cT4aN2M1 | pT4aN1, v3 |

| 9 | 65 | M | Sigmoid colon | cT4aN2M1 | pT4bN1, v3 |

| 10 | 60 | M | Transverse colon | cT3N0M0 | pT4aN2, v3 |

| 11 | 74 | F | Rectum | cT4aN2M0 | pT4aN2, v3 |

| 12 | 79 | F | Caecum | cT4aN1M0 | pT4aN1, v3 |

| 13 | 43 | F | Rectum | cT3N1M0 | pT3N1, v3 |

| 14 | 59 | M | Rectum | cT4aN2M1 | pT4bN1, v3 |

| 15 | 56 | M | Rectum | cT3N2M1 | pT3N1, v3 |

| 16 | 72 | M | Rectum | cT4aN2M0 | pT4aN1, v3 |

| 17 | 61 | F | Descending colon | Abscess | pT3N1, v3 |

| 18 | 49 | M | Rectum | cT4aN1M0 + abscess | pT3N1, v3 |

| 19 | 68 | F | Rectum | cT3N1M0 | pT3N1, v3 |

| 20 | 82 | M | Sigmoid colon | cT3N0M0 | pT3N0, v3 |

| 21 | 65 | M | Rectum | cT3N1M0 | pT3N1, v3 |

| 22 | 63 | M | Rectum | cT3N3M0 | pT3N2, v3 |

| 23 | 43 | F | Sigmoid colon | cT4aN1M1 | pT4bN0, v3 |

| 24 | 64 | F | Rectum | cT4bN0M1 | pT3N1, v3 |

| 25 | 63 | F | Sigmoid colon | cT3N0M0 | pT3N0, v3 |

| 26 | 84 | F | Rectum | cT3N1M0 | pT3N0, v3 |

cTNM, clinical TNM stage; F, female; M, male; pTNM, pathological TNM stage; v3, massive venous invasion.

CT findings

MVIs were located adjacent to the colon/rectum or along the IMV. MVI on CT was oval, lobulated, abscess-like or showed intravenous tumour thrombus pattern (Figures 1–4). Coronal or sagittal images of MPRs were helpful to evaluate these CT findings. Some MVIs looked like poorly enhanced solid nodules with well-enhanced rims (Figure 5). All of the LN metastases were oval and had homogeneous contrast enhancement (Figure 6).

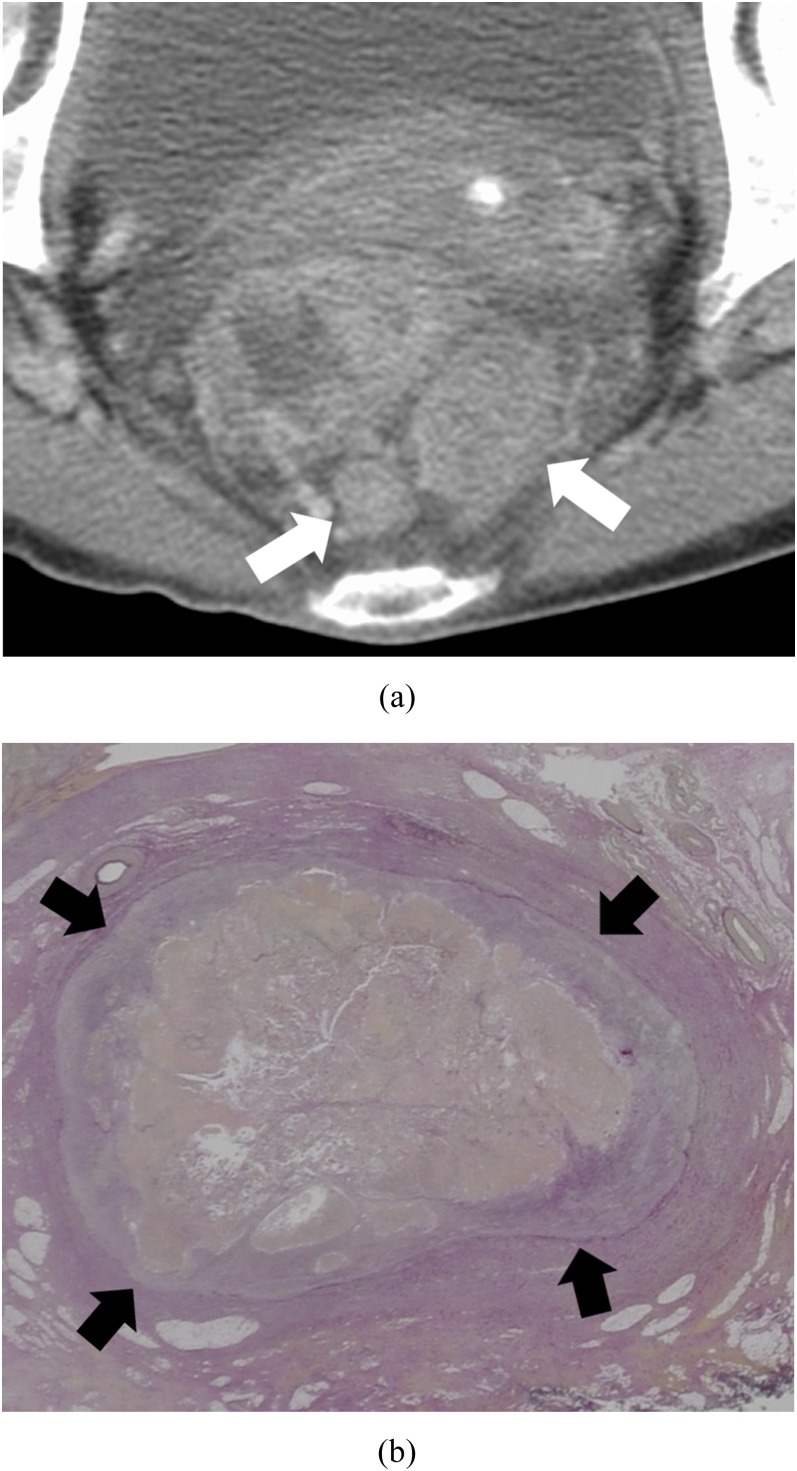

Figure 1.

Oval pattern: a 68-year-old female with massive venous invasion of rectal cancer. (a) Axial contrast-enhanced CT image of the pelvis. Two oval nodules (white arrows) can be found posterior to the rectum. (b) Histopathological image with Elastica van Gieson-stained section of one of the nodules. The tumour is surrounded by a continuous elastic membrane (black arrows) in the venous wall.

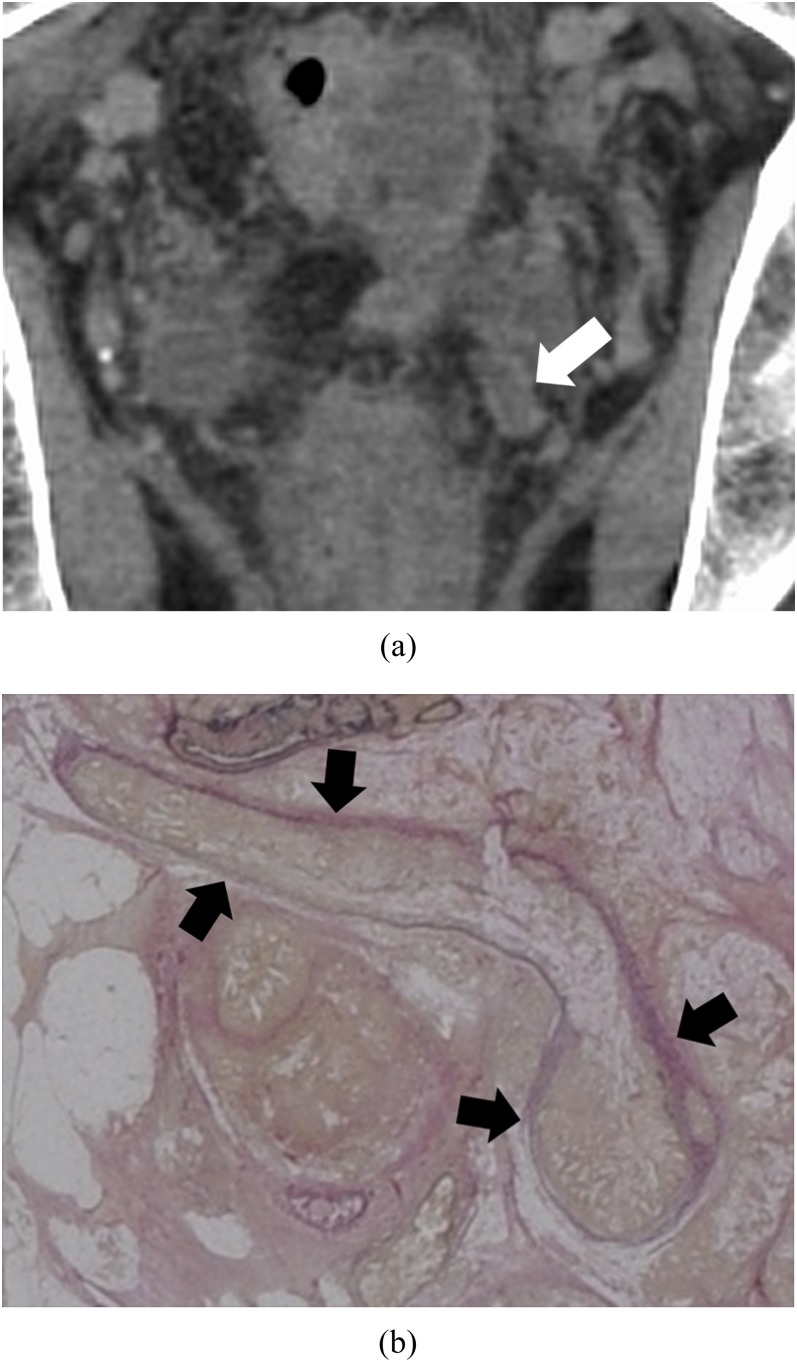

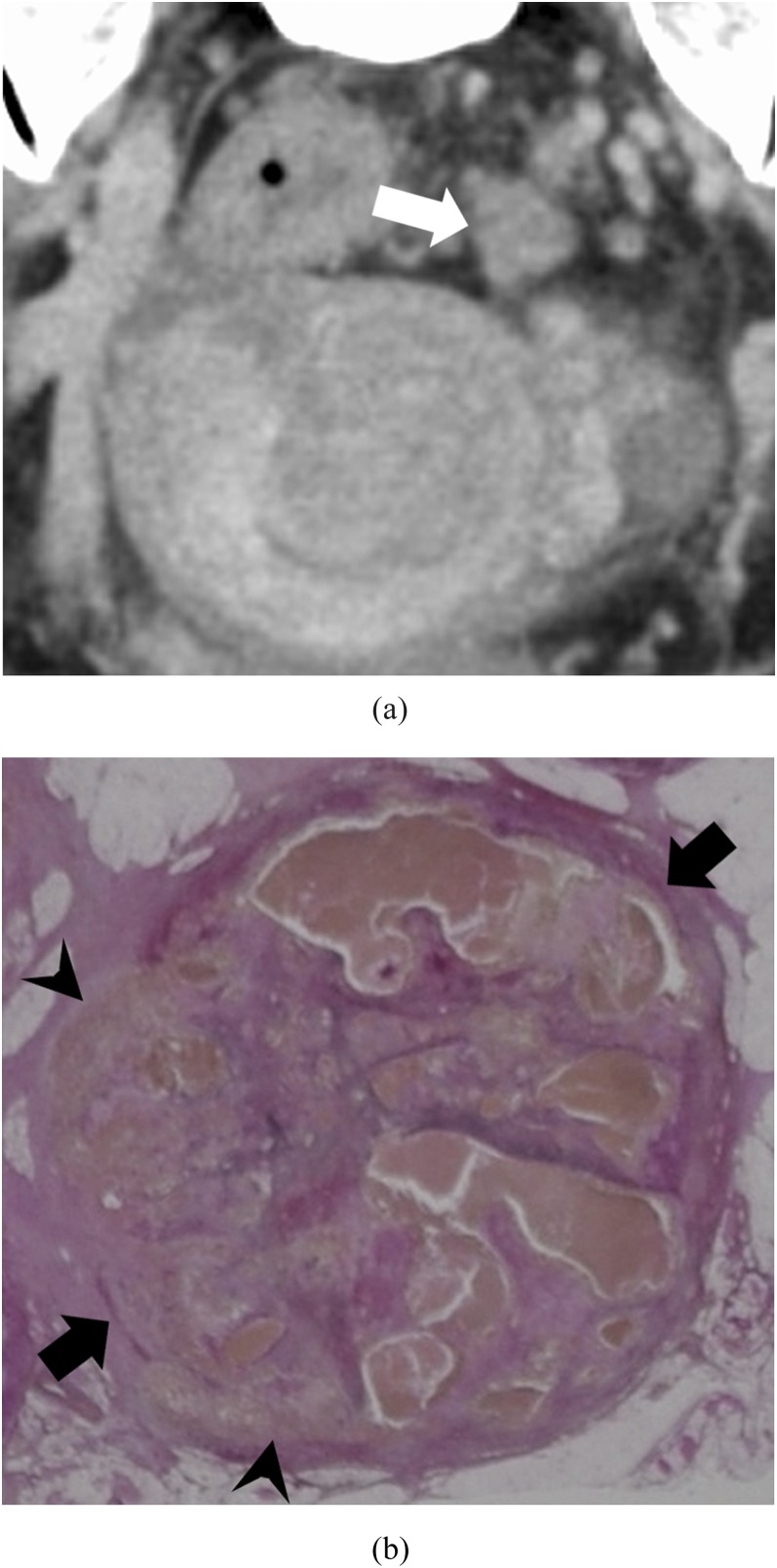

Figure 4.

Intravenous tumour thrombus pattern: a 63-year-old male with massive venous invasion of rectal cancer. (a) Coronal contrast-enhanced CT image of the pelvis. A rectangle nodule between parallel high-density lines can be found to the left of the rectum (white arrow). (b) Histopathological image with Elastica van Gieson-stained section of the nodule. There is a tumour in a vein whose elastic membrane is conserved (black arrows). The venous wall is thickened by stromal reaction.

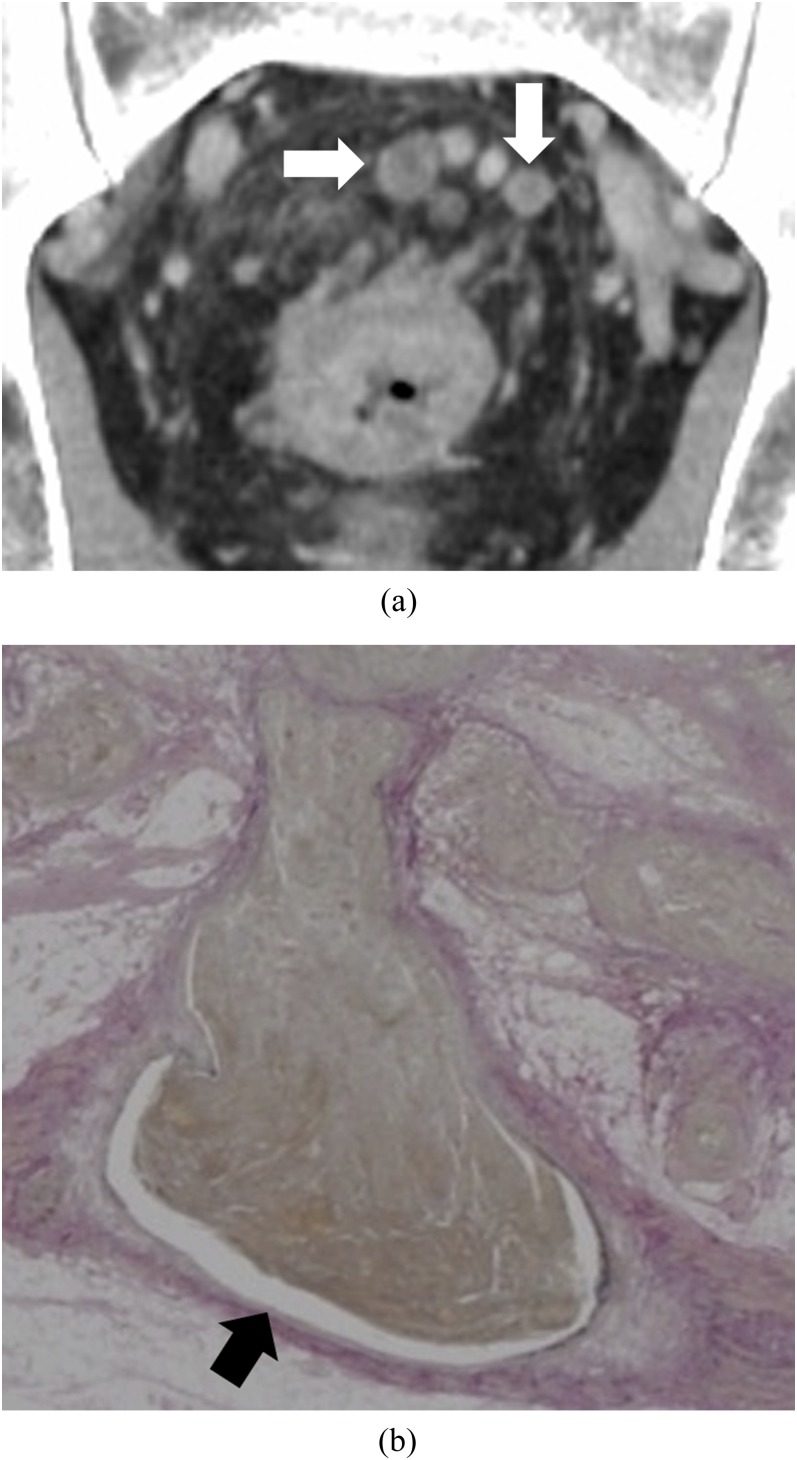

Figure 5.

Enhanced rim: a 59-year-old male with massive venous invasion of rectal cancer. (a) Coronal contrast-enhanced CT image of the pelvis. Two oval nodules with contrast-enhanced rim can be found superior to the rectum (white arrows). (b) Histopathological image with Elastica van Gieson-stained section of one of the nodules. There is a cavity between venous wall and tumour (black arrow).

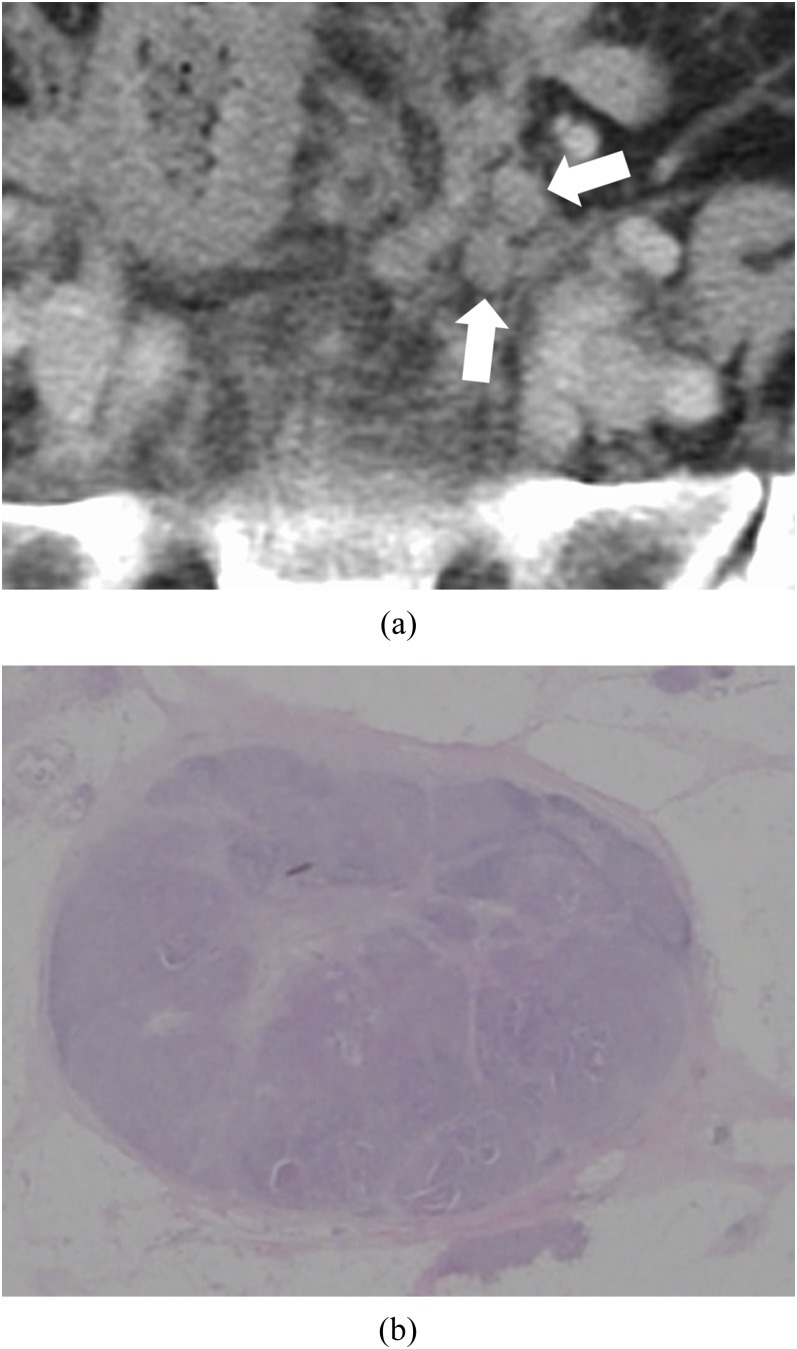

Figure 6.

Lymph node (LN) metastasis: a 74-year-old female with LN metastases of rectal–sigmoid colon cancer. (a) Axial contrast-enhanced CT image of the pelvis. Two oval nodules with homogeneous contrast enhancement can be found to the left side of the pelvis (white arrows). (b) Histopathological image with haematoxylin and eosin-stained section of one of the nodules. LN capsule is conserved. Lymph sinuses, lymphocytes and lymph follicles remain among tumours.

The Shapiro–Wilk test verified that the contrast enhancement of LN metastasis had normal distribution (p > 0.05). It did not verify the size of MVI and LN metastasis and the contrast enhancement of MVI as having normal distribution (p < 0.05). We used the Wilcoxon rank sum test to compare size and contrast enhancement.

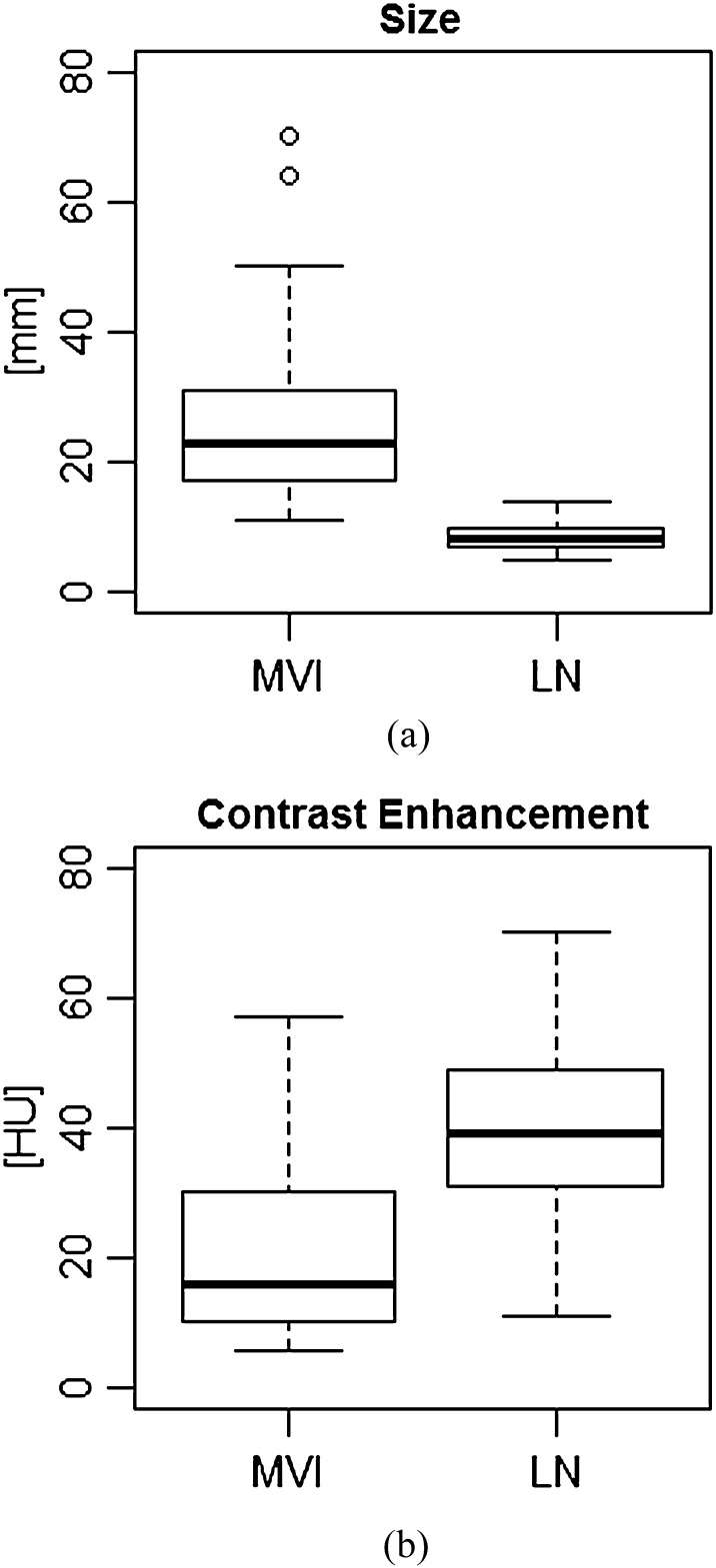

MVI (median, 23.0 mm; quartile deviation, 14.0 mm; n = 31) was significantly larger (p < 0.05) than LN metastasis (median, 8.0 mm; quartile deviation, 3.0 mm; n = 45), as shown in Figure 7. Contrast enhancement of MVI (median, 16.0 HU; quartile deviation, 20.0 HU; n = 31) was significantly lower (p < 0.05) than that of LN metastasis (median, 39.0 HU; quartile deviation, 18.0 HU; n = 45), as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Comparison of massive venous invasion (MVI) and lymph node (LN) metastasis in size (a) and contrast enhancement (b). Open circles are outliers of box plots. The numbers of samples are MVI, n = 31 and LN, n = 45. HU, Hounsfield units.

The spectrum of morphological patterns of MVI and LN are shown in Table 2. The morphological patterns of MVI were varied (nodule, abscess-like or intravenous tumour thrombus with enhanced rim), while all of the LN metastases were oval without enhanced rim. The spectrum of morphological pattern of MVI and LN were significantly different (p < 0.05) by Fisher's exact test.

Table 2.

The spectrum of morphological pattern of massive venous invasion (MVI) and lymph node (LN)

| Pattern | Enhanced rim | MVI case number | LN case number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oval | + | 4 | 0 |

| − | 3 | 45 | |

| Lobulated | + | 5 | 0 |

| − | 7 | 0 | |

| Abscess-like | + | 2 | 0 |

| − | 0 | 0 | |

| Intravenous tumour thrombus | + | 10 | 0 |

| − | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 31 | 45 |

+, present; −, absent.

CT-pathological findings

We investigated the histopathological background of the four typical CT appearances and the enhanced rim of MVI described above. We also investigated LN metastasis for comparison. Histopathological images contrasted with each CT appearances and LN metastases are shown in Figures 1–6, and the details are as follows:

• Oval MVI (Figure 1): macroscopically, the tumour contour was oval. Microscopically, the vascular lumen was filled with tumour cells. Although the smooth muscle layer of the tunica media was completely missing, the elastic membrane in the vessel wall was preserved throughout the whole circumference. Thick reactive fibrous tissue surrounded the vessel wall. The centre of the tumour underwent homogeneous necrosis, and nutrient arteries were not identifiable inside the tumour masses.

• Lobulated MVI (Figure 2): macroscopically, the tumour contour was ill-defined. Microscopically, the elastic membrane in the vessel wall was irregularly fractured. Tumour infiltrated the vein in several directions but was surrounded by intensive stromal reaction. The tumour underwent severe necrosis, and nutrient arterioles were identifiable inside the mass.

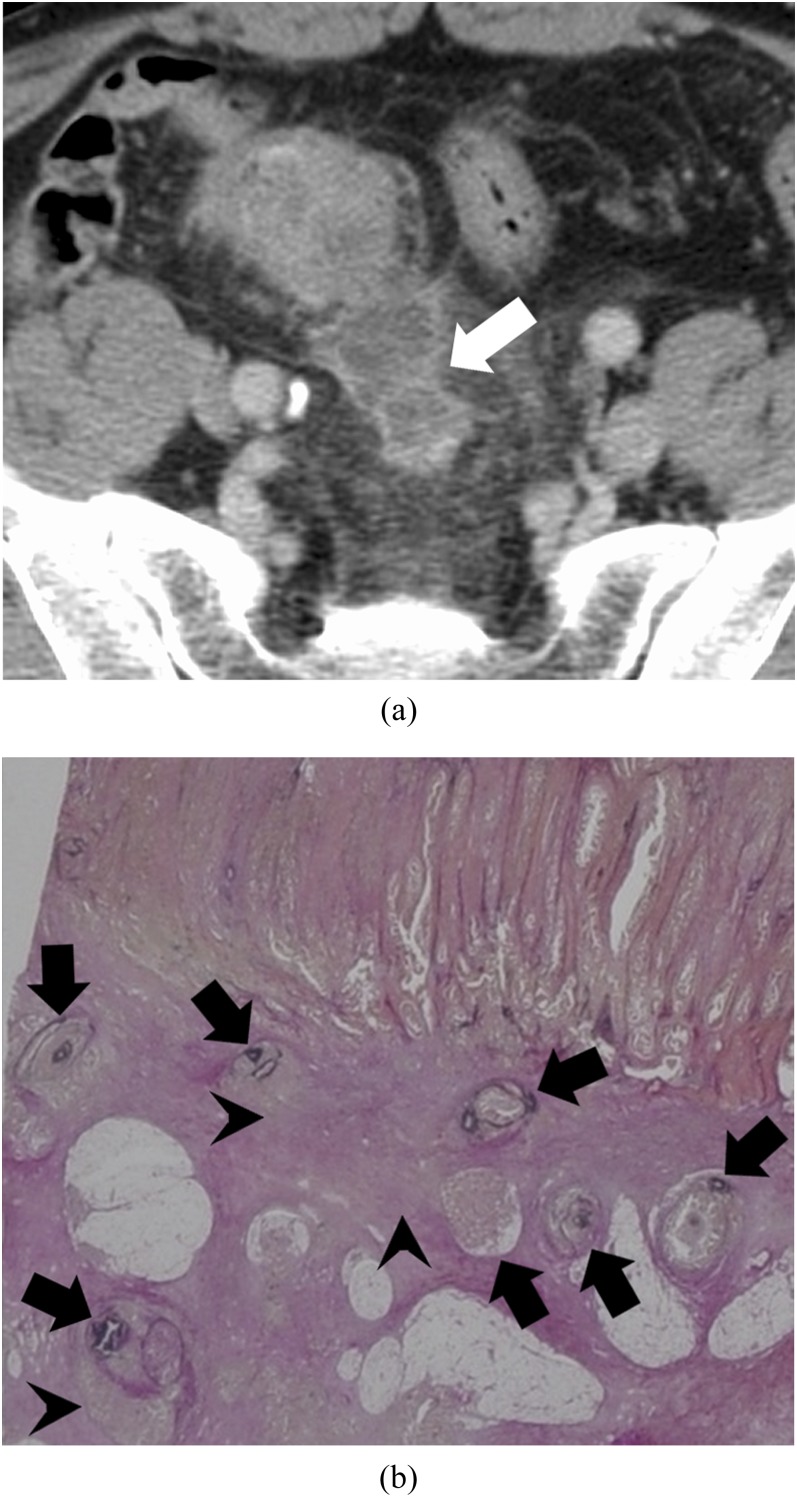

• Abscess-like MVI (Figure 3): microscopically, the tumour filled a cluster of small (perforating vein level) veins. Tumour invasion outside the vessel was also noted, and necrosis and stromal reaction were severe.

• Intravenous tumour thrombus (Figure 4): microscopically, the tumour occupied the lumen of a large vein (a main tributary of the IMV or the internal iliac vein). The elastic membrane in the vessel wall was preserved throughout the whole circumference. The vessel wall was reactively thickened.

• Enhanced rim of MVI (Figure 5): the tumour was limited to the lumen of a large vein (a main tributary of the IMV). There was a cavity between the tumour and venous wall, which contained scattered red blood cells. The tumour did not have feeding arteries, but it did not undergo necrosis.

• LN metastasis (Figure 6): the oval LN capsule was conserved, and the tumour was confined to the lumen of LN.

Figure 2.

Lobulated pattern: a 53-year-old female with massive venous invasion of rectal cancer. (a) Coronal contrast-enhanced CT image of the pelvis. A lobulated nodule (white arrow) can be found superior to the rectum. (b) Histopathological image with Elastica van Gieson-stained section of the nodule. There is fragmentation of the elastic membrane (black arrows). The tumour invades outward to the extra lumen, i.e. stroma (black arrowheads).

Figure 3.

Abscess-like pattern: a 49-year-old male with massive venous invasion of rectal cancer. (a) Axial contrast-enhanced CT image of the pelvis. An irregular-patterned lesion with its margin predominantly contrast-enhanced can be found in the middle of the pelvis (white arrow). (b) Histopathological image with Elastica van Gieson-stained section of the lesion. There are many small veins filled with tumours (black arrows). Some of tumours invade outward to the extra lumen, i.e. stroma (black arrowheads).

Follow-up

All 26 cases with MVI underwent follow-up CT examination after surgery. At the time of presentation, 10 cases (38.5%) had synchronous distant metastases and 16 cases (61.5%) had no distant metastasis. 6 of 16 cases (37.5%) without synchronous distant metastasis had metachronous distant metastasis during follow-up period (1–17 months, average 6.5 months) and another one had local LN metastases (4 months). The remaining 9 cases had not metastasized during follow-up (6–56 months, average, 29.3 months). Eight cases among the whole MVI group died, and three of them were cases without synchronous distant metastasis. The mortality of the whole MVI group was 30.8% (survival time, 1–17 months; average, 11.3 months), and the mortality of cases without synchronous distant metastasis was 18.8% (survival time, 9–11 months; average, 10.0 months). All 26 patients of the LN group also underwent follow-up CT examination. At the time of presentation, one case (3.8%) had synchronous distant metastases in the liver. 1 of 25 cases (4.0%) without synchronous distant metastasis had metachronous distant metastasis during the follow-up period (11 months) and another had local LN metastases during follow-up period (3 months). The remaining 23 cases had not metastasized during follow-up (6–47 months, average, 23.7 months). Three cases among the whole LN group died, and one of them was a case without synchronous distant metastasis. The mortality of the whole LN group was 11.5% (survival time, 9–20 months; average, 14.5 months), and the mortality of cases without synchronous distant metastasis was 4.0% (survival time, 20 months). The sites and frequencies of metastases are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Sites and number of cases of metastasis

| Site | Number of cases with massive venous invasion (n = 26) |

Number of cases of confirmed lymph node metastasis (n = 26) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Synchronous metastasis (%) | Metachronous metastasis (%) | Synchronous metastasis (%) | Metachronous metastasis (%) | |

| Liver |

9 (34.6) |

10 (38.5) |

1 (3.8) |

2 (7.7) |

| Lung | 2 (7.7) | 6 (23.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.8) |

| Bone | 0 (0) | 2 (7.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Pancreas | 0 (0) | 1 (3.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Adrenal gland | 0 (0) | 1 (3.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Ovary | 1 (3.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Peritoneum | 1 (3.8) | 2 (7.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.8) |

| Lymph node | 17 (65.4) | 9 (34.6) | 26 (100) | 2 (7.7) |

| None | 6 (23.1) | 12 (46.2) | 0 (0) | 23 (88.5) |

The distributions of the synchronous and metachronous metastatic sites and frequency were significantly different (p < 0.05) between patients with MVI and the LN group by Fisher's exact test.

DISCUSSION

There are no widely accepted standards or guidelines for the pathological evaluation of venous invasion by tumours. TNM staging is not influenced by venous invasion, so radiologists do not pay much attention to differentiating LN metastases and venous invasion on CT. Although many studies on T and N staging of colorectal cancer by CT have been reported, most of them did not describe the pathological findings of LN metastasis in detail. However, if tumour cells completely replace LN structures and lymph sinuses, lymphocytes or lymph follicles disappear, and pathologists do not use EVG stain to accurately identify venous structure, distinction between LN metastasis and venous invasion appeared to be difficult. In this study, we used EVG stain to distinguish MVI from LN metastasis and found MVI had various features on CT. From our review in this study, CT was able to detect considerable cases of MVIs (20 of 26 cases), but they were misdiagnosed pre-operatively as LN metastasis or juxtatumoural abscess. This appeared to be partly due to the location of MVI (i.e. adjacent to the primary tumours). The patterns of MVI on CT findings were not uniform, and we found that they were related to the size of vein, integrity of the venous wall and number of veins involved. Compared with the walls of arteries, walls of veins are thinner with less smooth muscle and elastic tissue. When the elastic membrane in the vessel wall is preserved (as it tends to be in large veins such as the main tributary of the IMV or the internal iliac vein), the margins of tumours stay within the venous lumen (oval, tumour thrombus or enhanced rim pattern). When the elastic membrane in the vessel wall is not preserved (as it tends not to be in small- or medium-sized veins), the tumours can grow in every direction, and the margins of the tumours become irregular (lobulated and abscess-like patterns).

We noted a difference in contrast enhancement between MVI and LN metastasis in this study, likely caused by the differences in blood flow. An intravenous tumour may not have an arterial blood supply, while a LN has a couple of hilar arteries and veins.27 Our histopathological examinations proved that tumours in MVI often lacked nutrient arteries and underwent necrosis. The highly enhanced rim of the venous invasion of cancer is probably vascular space (with contrast material) around the tumour and/or the enhanced reactive stroma surrounding the vessel wall. Made of dense connective tissue mentioned above, the LN capsule is not as well enhanced as vascular space or vessel wall.

As previous studies demonstrated,3–15 MVI is considered as a risk factor of metachronous distant metastasis. In our study, the rate of synchronous distant metastasis was much higher in the cases with MVI (38.5%) than those in the LN group (3.8%). Among the patients who did not have synchronous distant metastasis, the rate of developing metachronous distant metastasis was much higher in the cases with MVI (37.5%) than in cases in the LN group (4.0%) and the period until metachronous distant metastasis presented after surgery was shorter in cases with MVI (average 6.5 months) than in the LN group (11 months). Mortality was higher in cases with MVI (30.8%) than in those of the LN group (11.5%), and the survival time was shorter in cases with MVI (average, 11.3 months) than in those of the LN group (average, 14.5 months).

In previous reports3–15 and from the clinical courses of our cases, we think MVI is an important predictor for distant metastasis, and its identification on a pre-operative CT may indicate a need for additional search for distant metastasis, such as MRI and/or fluorine-18 fludeoxyglucose–positron emission tomography, and a need for neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The finding of MVI may propose the need for adjuvant chemotherapy and closer follow-up after surgery. Previous reports3–15 also indicated the importance of MVI for prediction of prognosis being the same as the staging system. We hope that this study will draw attention to the importance of MVI in planning treatment of colorectal cancer.

This study has several limitations. First, the biggest limitation of our study is the obviously small population size. Second, a retrospective study may cause overinterpretation of CT images of MVIs and LNs. The pathologist informed the two radiologists of the existence of MVIs and LNs, and the two radiologists referred to pre-operative CT reports, which could bias their findings even though the radiologists were blinded to the histopathological images, morphological patterns and precise locations of the lesions when they evaluated the CT images. Seeking MVIs and LNs on CT images without pathological information is a prospective and beyond the scope of this study. Third, matching of sex, age or clinical disease stage between the MVI group and LN group was insufficient. The primary aim of this study was to identify MVIs and differentiate MVIs from LNs on CT. We selected the patient population with genuine LN metastases as the top priority to compare with MVIs on CT. We, thus, could not but lower the priority of coordinating patient characteristics between the MVI and LN groups. What should be noted, however, is that MVI was an independent risk factor as demonstrated by previous studies.6–15 This limitation was also related to the small population size. Fourth, there was a limitation on the method in evaluating lesions on CT and processing histopathological section. As described above, two nodules from the LN group were not classifiable into LN metastasis or MVI. These nodules were oval with enhanced rim on CT, but histopathologically had lost any characteristic structures of LN or vein. The two nodules were filled with necrotic tumour and surrounded by connective tissue, stromal reaction and slightly elastic fibres. It is impossible to classify such a nodule into MVI or LN metastasis completely. We excluded these two nodules from the data in this study. Finally, our follow-up period was short (56 months at the most and 6 months at the least), and this fact appeared to limit the detected rate of metachronous metastasis.

CONCLUSIONS

The majority of MVI were identifiable in retrospect on pre-operative CT of colorectal cancer, and their appearances were varied, reflecting the histopathological behaviour of the lesions. Node-like MVIs (oval and lobulated pattern) mimicked LN metastases and their percentage among MVIs in this study was 61.3% (19 of 31 MVIs). The size and enhancement of MVI were significantly different from those of the LN metastasis. The detection of MVI on CT findings may be a sentinel sign of distant metastasis and would help the treatment planning of colorectal cancer.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sobin L, Gospodarowicz M, Wittekind C, eds. International union against cancer (UICC) TNM classification of malignant tumours. 7th edn. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009. pp. 100–5. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A, eds. AJCC cancer staging manual. 7th edn. New York, NY: Springer; 2010. pp. 145–75. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Compton CC. Colorectal carcinoma: diagnostic, prognostic, and molecular features. Mod Pathol 2003; 16: 376–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Compton CC, Fielding LP, Burgart LJ, Conley B, Cooper HS, Hamilton SR, et al. Prognostic factors in colorectal cancer. College of American Pathologists consensus statement 1999. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2000; 124: 979–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Compton CC, Fenoglio-Preiser CM, Pettigrew N, Fielding LP. American Joint Committee on cancer prognostic factors consensus conference: colorectal working group. Cancer 2000; 88: 1739–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chapuis PH, Dent OF, Fisher R, Newland RC, Pheils MT, Smyth E, et al. A multivariate analysis of clinical and pathological variables in prognosis after resection of large bowel cancer. Br J Surg 1985; 72: 698–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Newland RC, Dent OF, Lyttle MN, Chapuis PH, Bokey EL. Pathologic determinants of survival associated with colorectal cancer with lymph node metastases. A multivariate analysis of 579 patients. Cancer 1994; 73: 2076–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wiggers T, Arends JW, Volovics A. Regression analysis of prognostic factors in colorectal cancer after curative resections. Dis Colon Rectum 1988; 31: 33–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freedman LS, Macaskill P, Smith AN. Multivariate analysis of prognostic factors for operable rectal cancer. Lancet 1984; 2: 733–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harrison JC, Dean PJ, el-Zeky F, Vander Zwaag R. From Dukes through Jass: pathological prognostic indicators in rectal cancer. Hum Pathol 1994; 25: 498–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knusen JB, Nilsson T, Sprechler M, Johansen A, Christensen N. Venous and nerve invasion as prognostic factors in postoperative survival of patients with resectable cancer of the rectum. Dis Colon Rectum 1983; 26: 613–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heys SD, Sherif A, Bagley JS, Brittenden J, Smart C, Eremino O. Prognostic factors and survival of patients aged less than 45 years with colorectal cancer. Br J Surg 1994; 81: 685–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maruoka Y, Maetani S, Tobe T. Statistical analysis of pathological factors influencing prognosis of colorectal carcinoma. [In Japanese.] Nihon Geka Gakkai Zasshi 1988; 89: 181–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Talbot IC, Ritchie S, Leighton MH, Hughes AO, Bussey HJ, Morson BC. The clinical significance of invasion of veins by rectal cancer. Br J Surg 1980; 67: 439–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamazoe Y, Maetani S, Onodera H, Nishikawa T, Tobe T. Histopathological prediction of liver metastasis after curative resection of colorectal cancer. Surg Oncol 1992; 1: 237–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Japanese Society for Cancer of Colon and Rectum. General rules for clinical and pathological studies on cancer of the colon, rectum and anus. 7th edn. Tokyo, Japan: Kanehara; 2009. pp. 30. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sato T, Ueno H, Mochizuki H, Shinto E, Hashiguchi Y, Kajiwara Y, et al. Objective criteria for the grading of venous invasion in colorectal cancer. Am J Surg Pathol 2010; 34: 454–62. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181d296ef [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Cutsem EJ, Oliveira J; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Advanced colorectal cancer: ESMO clinical recommendations for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2008; 19(Suppl. 2): ii33–4. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum. JSCCR guidelines 2010 for the treatment of colorectal cancer. Tokyo, Japan: Kanehara; 2010. pp. 50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsumoto J, Kojima T, Hiraguchi E, Abe M. Portal vein tumor thrombus from colorectal cancer with no definite metastatic nodules in liver parenchyma. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2009; 16: 688–91. doi: 10.1007/s00534-009-0061-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tanoue Y, Tanaka N, Suzuki Y, Hata S, Yokota A. A case report of endocrine cell carcinoma in the sigmoid colon with inferior mesenteric vein tumor embolism. World J Gastroenterol. 2009; 15: 248–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dighe S, Blake H, Koh MD, Swift I, Arnaout A, Temple L, et al. Accuracy of multidetector computed tomography in identifying poor prognostic factors in colonic cancer. Br J Surg 2010; 97: 1407–15. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown G, Radcliffe AG, Newcombe RG, Dallimore NS, Bourne MW, Williams GT. Preoperative assessment of prognostic factors in rectal cancer using high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging. Br J Surg 2003; 90: 355–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith NJ, Barbachano Y, Norman AR, Swift RI, Abulafi AM, Brown G. Prognostic significance of magnetic resonance imaging-detected extramural vascular invasion in rectal cancer. Br J Surg 2008; 95: 229–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vass DG, Ainsworth R, Anderson JH, Murray D, Foulis AK. The value of an elastic tissue stain in detecting venous invasion in colorectal cancer. J Clin Pathol 2004; 57: 769–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suzuki A, Togashi K, Nokubi M, Koinuma K, Miyakura Y, Horie H, et al. Evaluation of venous invasion by Elastica van Gieson stain and tumor budding predicts local and distant metastases in patients with T1 stage colorectal cancer. Am J Surg Pathol 2009; 33: 1601–7. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181ae29d6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Willard-Mack CL. Normal structure, function, and histology of lymph nodes. Toxicol Pathol 2006; 34: 409–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]