Abstract

A new imaging technique for the analysis of fluorescent pigments from a single cell is reported. It is based on confocal scanning laser microscopy coupled with spectrofluorometric methods. The setup allows simultaneous establishment of the relationships among pigment analysis in vivo, morphology, and three-dimensional localization inside thick intact microbial assemblages.

Phototrophic organisms produce a number of photosynthetic pigments that act as photoactivated fluorescent markers that switch on in response to light at a particular wavelength. A fraction of the energy absorbed by pigments may be emitted immediately at a longer wavelength, which is known as fluorescence (7). Fluorescence allows the description of a complex community in terms of physiological state (17), discrimination among phylogenetic groups (8), quantification of biomass (2), energy transfer, and cell evolution (4). Approaches to improve the use of cellular fluorescence techniques with subsequent localization of the organisms in two dimensions (2D) or 3D (15, 10) have been reported.

Here we propose a new application of the confocal scanning laser microscope (CSLM) coupled with a spectrofluorometric detector. Confocal imaging spectrofluorometry provides simultaneous 3D information on photosynthetic microorganisms and their fluorescence signatures within thick assemblages (as in microbial mats, biofilms, etc.) because of their multiple excitation wavelengths (λexcs) and free detection of emitted wavelengths. We report our results on pigments, pure cultures, and biofilms from dim-light environments.

Pigments.

The pure pigments chlorophyll a (Chl a) and Chl b, xanthophyll (Xant), R-phycoerythrin, allophycocyanin-XL (APC-XL), and C-phycocyanin (C-PC), all obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, Mo.), were used as controls. Pigment solutions were set at a final concentration of 1 mg/ml, and scans were done as described below.

Culture and biofilm preparation.

Two cultures of Nostoc humifusum Carm. (Cyanobacteria) and Muriellopsis sp. (Chlorophyta) at distinct stages of growth (exponential phase, 1 week; stationary phase, 3 weeks) and three stratified aerophytic biofilms from dim habitats, BF1, BF2, and BF3, which are described and identified elsewhere (6), were tested. The biofilms contained several photosynthetic phylogenetic groups (Cyanobacteria, Chlorophyta, and Bacillariophyta).

CSLM.

CSLM was performed with a Leica TCS-SP2 (Leica Microsystems, Mannheim, Germany). The wavelengths of the excitation lasers were in the UV Ar (351 and 364 nm), blue Ar (458, 476, and 488 nm), green Ar (514 nm), green HeNe (543 nm), and red HeNe (633 nm) spectra. Each image sequence (wavelength scans or lambda scan function of the system) was obtained by scanning the same x-y optical section with a λ step size of 20 nm for emission wavelengths between 360 and 800 nm. The x, y, λ data set was acquired at the z position at which the fluorescence was maximal, and acquisition settings were not altered throughout the experiments. The variation in intensity of a particular spectral component, encoded with 8 bits, is represented on the screen with a pseudocolor lookup table. 3D maximum-intensity projections were made with Imaris software (version 2.7; Bitplane AG, Zürich, Switzerland).

Fluorescence analysis.

The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the x-y-λ data sets was measured with the Leica Confocal Software, version 2.0. The region-of-interest (ROI) function of the software was used to determine the spectral signature of a selected area of the scanned image. For pigment solutions, we analyzed ROIs of 1,000 μm2 (10 regions). For cell culture and biofilm analysis, ROIs of 1 μm2, taken from the fluorescent thylakoid region inside the cell, were set in each x-y-λ stack of images. A patent application related to this technology has been filed (no. 200302905, 27 November 2003, Spain).

Lambda scans of N. humifusum (21 ROIs), Muriellopsis sp. (50 ROIs), and biofilms (5 ROIs for each species in the biofilm) were obtained for each λexc in three independent experiments. 3D plots—MFI to longer-wavelength emission versus cell number—were obtained with Matlab 6.0 (Mathworks, Inc.). The mean and standard error for all of the regions or cells examined in each λexc were calculated. The maxima of the pigments corresponded to their dispersion range at the distinct λexc.

Lambda scans of the pure pigments (Fig. 1 and 2) correlated well with published spectra of extracted pigments (11, 13, 14). All species had a Chl a fluorescence maximum at 680 to 690 nm, while those belonging to the same phylogenetic group, Cyanobacteria, Chlorophyta, or Bacillariophyta, showed similar spectra (Fig. 1 to 3) because of the presence of characteristic pigments (8).

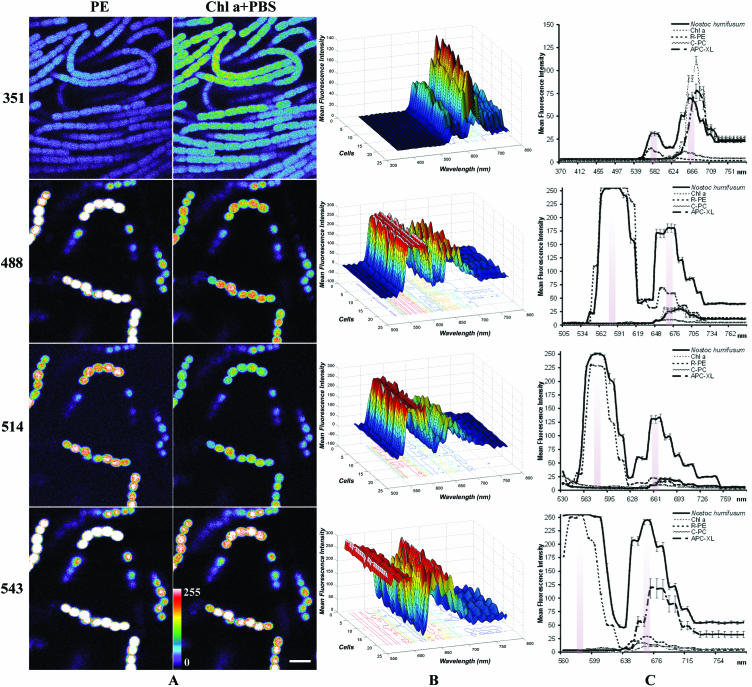

FIG. 1.

CSLM images and lambda scans of N. humifusum in vivo. These optical sections and spectral profiles were derived at λexcs of 351, 488, 514, and 543 nm. (A) Pseudocolor confocal x-y-λ single sections corresponding to the λmax autofluorescence of C-PE (first maximum) and Chl a plus phycobiliproteins (PBS) (second maximum) at each of the four λexcs. The pseudocolor scale is shown at the bottom left. Warm colors such as white and red represent maximum intensities, whereas cold colors like blue are representative of low intensities (the intensity of each pixel was set to 255 levels of grey). Such optical sections correspond to the maximum peaks when excited at the corresponding λexc, shown in C plots (shady areas). (B) 3D surface pseudocolor plots of fluorescence spectra: emission wavelength, x; MFI, y; number of cells, z. The λmax position of each cell showed practically no variability at each λexc, even if the cultures were in different states of growth. (C) 2D plots representing the MFI spectra of N. humifusum and pure pigments. Standard errors (n = 21cells) and R-phycoerythrin, C-PC, APC-XL, and Chl a (n = 10 regions) MFI spectra at these λexcs are represented. Ratios of C-PC and APC-XL fluorescence had to be multiplied by a factor of 2 owing to the weak fluorescence signal received by the CSLM. Each value shown is the average MFI from three independent experiments carried out under the same conditions. Scale bar = 10 μm.

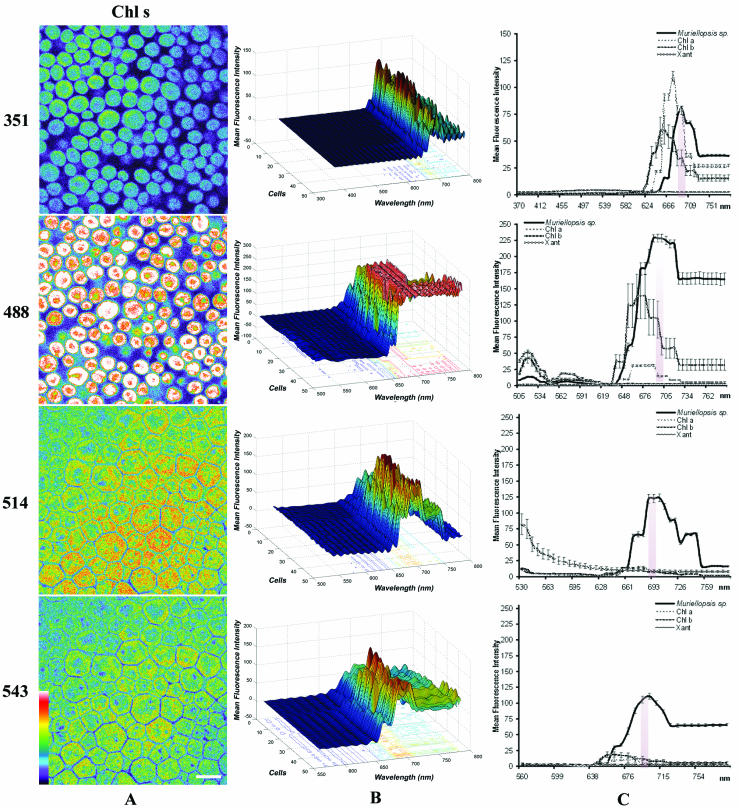

FIG. 2.

CSLM images and lambda scans of Muriellopsis sp. in vivo. These optical sections and spectral profiles were derived at λexcs of 351, 488, 514, and 543 nm. (A) Pseudocolor confocal x-y-λ single sections corresponding to the λmax autofluorescence of Chl a and Chl b for each of the four λexcs. The pseudocolor scale is shown at the bottom left. Such optical sections correspond to the maximum peaks when excited at the corresponding λexcs, shown in C plots (shady areas). (B) 3D surface pseudocolor plots of fluorescence spectra: emission wavelength, x; MFI, y; number of cells, z. The λmax position of each cell showed practically no variability in the λexc, even if the cultures were at different stages of growth. (C) 2D plots representing the MFI spectra for Muriellopsis sp. and pure pigments. Emission spectra are the mean ± standard error (n = 50 cells), and Xant, Chl a, and Chl b pigments (n = 10 regions) in each λexc are represented. The ratio of Xant fluorescence had to be multiplied by a factor of 2 owing to the weak fluorescence signal received by the CSLM. Scale bar = 10 μm.

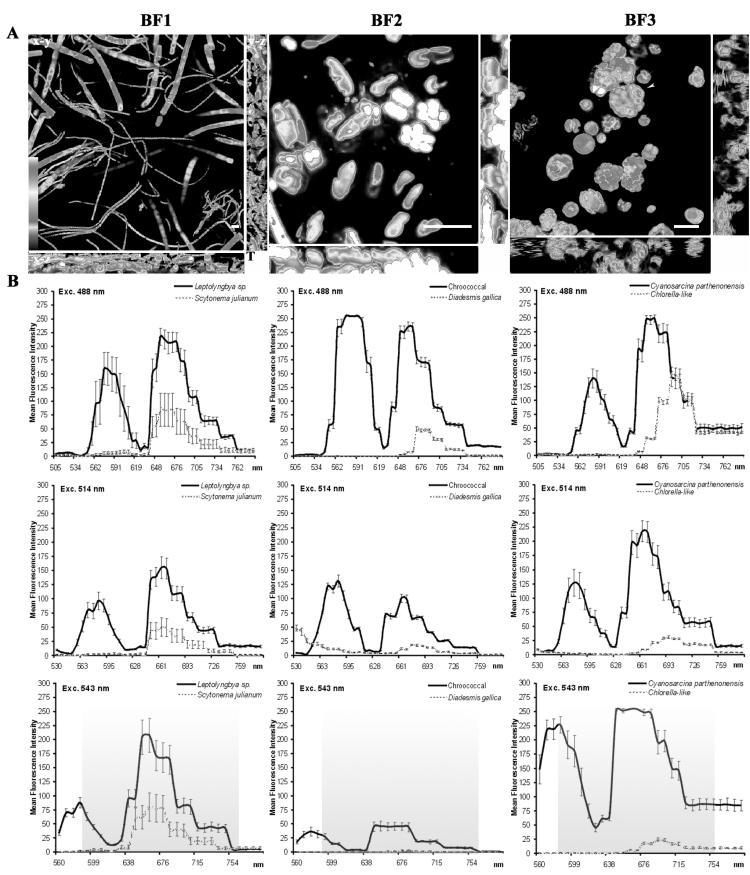

FIG. 3.

CSLM images and lambda scans of three in vivo aerophytic biofilms from the Roman catacombs (BF1 and BF2) and Zuheros (BF3). Optical sections and spectral profiles derived from λexcs of 351, 488, 514, and 543 nm. (A) 3D maximum-intensity projections in the x-y direction and orthogonal views in the z direction of the biofilm. Each image represents the maximum autofluorescence emitted in the range of 590 to 775 nm (shady area) when excited at 543 nm. The pseudocolor scale is shown at the bottom left. T = surface of the sample. Scale bar = 10 μm. BF1, 49 x-y optical sections of S. julianum and Leptolyngbya sp. The voxel size is 465.03 by 465.03 by 398.73 nm3. z step, 0.4 μm. Thickness, 19.54 μm. BF2, 66 x-y optical sections of a stratified biofilm consisting of two strata, an upper epilithic layer composed of colonies of D. gallica and an understorey layer formed by chroococcal colonies. The voxel size is 75.82 by 75.82 by 98.51 nm3. z step, 0.1 μm. Thickness, 6.6 μm. BF3, 98 x-y optical sections of a stratified biofilm with a continuous upper layer of Chlorella-like organisms and a discontinuous bottom layer of C. parthenonensis (arrow). The voxel size is 146.77 by 146.77 by 200 nm3. z step = 0.2 nm3. Thickness, 19.4 μm. (B) In vivo mean emission spectra of the different species present in the biofilms of panel A and the standard error (five cells). The emission difference profiles of the biofilms indicate the presence of different groups of algae and cyanobacteria.

Fluorescence properties of single x-y-λ sections of N. humifusum, corresponding to the emission peak (λmax), were obtained for each pigment at each λexc (Fig. 1). From these sections, the ROIs used to plot 3D and 2D spectral data (Fig. 1B and C) were obtained. The emission maximum of Chl a was observed at a 351-nm λexc and showed a weak shoulder when close to the phycobiliprotein fluorescence maximum at 663 ± 1.5 nm (Fig. 1C) (4). The 488-, 514-, and 543-nm λexc, absorbed essentially by C-phycoerythrin (C-PE), resulted in strong orange fluorescence emission at 579 ± 1.6 nm in vivo. These results are consistent with those previously reported (12, 16, 15).

Muriellopsis sp. (Fig. 2) showed a prominent Chl a fluorescence peak at 696.5 ± 2.4 nm when excited at any λexc (Fig. 2C). This Chl a peak shifted (∼10 nm) to a longer wavelength than generally reported for λexc. This shift may be a result of the interaction of the Xant lutein (5) with Chl a (1, 18). Furthermore, the presence of Chl b affected the state of the longer-wavelength-absorbing forms of Chl a (3, 9).

3D maximum-intensity projections of three biofilms showed the differential distribution in depth of the forming microorganisms (Fig. 3A) and emission spectra (Fig. 3B). In biofilm BF1, thin filaments of Leptolyngya sp. were horizontally oriented on top of wide Scytonema julianum (Fig. 3A). Both cyanobacteria had a wide 658.4 ± 3-nm λmax emission peak from the overlap of Chl a and phycobiliproteins (Fig. 3B). In addition, the emission peak (579.7 ± 3.8 nm) of Leptolyngybya sp., but not that of S. julianum, was attributable to the presence of C-PE (Fig. 3B). In biofilm BF2, Diadesmis gallica (Bacillariophyta) was mainly on the top of the biofilm while chroococcal cyanobacteria formed a discontinuous bottom layer (Fig. 3A). The λmax of D. gallica, at 676.2 ± 5 nm (Fig. 3B), did not coincide with the λmax of the other groups because of the presence of Chl c. The chroococci showed spectra similar to those of Leptolyngybya sp. and N. humifusum (Fig. 1 and 3). Biofilm BF3 was also stratified, with a continuous upper layer of Chlorella-like organisms and isolated colonies of Cyanosarcina parthenonensis in deeper parts (Fig. 3A). Their λmax matched those of the related groups Chlorophyta and Cyanobacteria, respectively (Fig. 1 to 3).

Statistical test.

A parallel experiment to compare the MFIs of species in culture at distinct λexcs was carried out. The emission ranges used were 640 to 700 nm (351-nm λexc), 555 to 605 nm (488-nm λexc), and 580 to 620 nm (543-nm λexc). Twenty-five replicates of each taxon, each composed of 20 optical sections at a z step of 0.45 μm, were obtained. These sections were processed by Metamorph image analysis software to obtain a composite image in which the total fluorescence was quantified. Differences between the MFIs of species in culture at different λexcs were evaluated by two-way analysis of variance (fixed factors) with statistical significance set to 0.05. When significant differences were observed, means were compared by the least significant differences of Fisher's multirange test. The MFI was significantly different between species (F1, 137 = 413.49, P < 0.0001) and between λexcs (F2, 137 = 14.57, P < 0.0001). The interaction term was also significant (F2, 137 = 99.65, P < 0.0001) owing to the different set of pigments of each species. For MFI at a 351-nm λexc, which corresponds mainly to chlorophyll fluorescence, the results were similar for N. humifusum and Muriellopsis sp. In contrast, for MFI at 488- and 543-nm λexcs, the outcome for N. humifusum was higher than that for Muriellopsis sp. The λexcs used here are reported to be the most suitable for detecting phycobiliproteins (8). The Cyanobacteria in field samples presented a higher MFI for the range of 640 to 740 nm at any of the λexcs compared to Chlorophyta and Bacillariophyta (Fig. 3B). The Cyanobacteria also showed a high MFI at λmaxs of 577 to 580 nm (Fig. 3B) because of the C-PE. We did not observe changes in the λmax of particular taxa—N. humifusum, S. julianum, or C. parthenonensis—when they were covered by thick sheaths, exopolymeric substances, or calcareous investments.

Conclusions.

The combination of CSLM with spectrofluorometry techniques provides a powerful tool that extends the application fields of these two methodologies. This setup allows (i) direct analysis for global and single fluorescent pixels and their 3D localization in vivo, thus minimizing the artifacts associated with a small sample size, and (ii) discrimination of cells with particular fluorescence signatures within a colony and correlation with morphology and individual cell states.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the EU Program Energy, Environment, and Sustainable Development in the frame of CATS Project contract EVK4-CT-2000-00028.

We thank Herminia Rodríguez for supplying species in culture and the Scientific and Technical Services of the University of Barcelona for helpful assistance with the CSLM. We thank Elisabet Yuste for her contribution to the experimental work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersson, P. O., T. Gillbro, A. E. Asato, and R. S. H. Liu. 1992. Dual singlet state emission in a series of mini-carotenes. J. Lumin. 51:11-20. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Becker, G., H. Holfeld, A. T. Hasselrot, D. M. Fiebig, and D. A. Menzler. 1997. Use of a microscope photometer to analyze in vivo fluorescence intensity of epilithic microalgae grown on artificial substrata. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:1318-1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bialek-Bylka, G. E., and J. S. Brown. 1986. Spectroscopy of native chlorophyll-protein complexes embedded in polyvinyl alcohol films. Photobiochem. Photobiophys. 13:63-71. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell, D., V. Hurry, A. K. Clarke, P. Gustafsson, and G. Öquist. 1998. Chlorophyll fluorescence analysis of cyanobacterial photosynthesis and acclimation. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:667-683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Del Campo, J. A., J. Moreno, H. Rodriguez, M. A. Vargas, J. Rivas, and M. G. Guerrero. 2000. Carotenoid content of chlorophycean microalgae: factors determining lutein accumulation in Muriellopsis sp. (Chlorophyta). J. Biotechnol. 76:51-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hernández-Mariné, M., E. Clavero, and M. Roldán. 2003. Why there is such luxurious growth in the hypogean environments. Arch. Hydrobiol. Algol. Stud. 148:229-240. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keränen, M., E.-M. Aro, and E. Tyystjärvi. 1999. Excitation-emission map as a tool in studies of photosynthetic pigment-protein complexes. Photosynthetica 37:225-237. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Millie, D. F., O. M. E. Schofield, G. J. Kirkpatrick, G. Johnsen, and T. J. Evens. 2002. Using absorbance and fluorescence spectra to discriminate microalgae. Eur. J. Phycol. 37:313-322. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mullet, J. E., J. J. Burke, and C. J. Arntzen. 1980. A developmental study of photosystem I peripheral chlorophyll proteins. Plant Physiol. 65:823-827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neu, T. R., U. Kuhlicke, and J. R. Lawrence. 2002. Assessment of fluorochromes for two-photon laser scanning microscopy of biofilms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:901-909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ong, L. J., and A. N. Glazer. 1987. R-phycocyanin II, a new phycocyanin occurring in marine Synechococcus species. Identification of the terminal energy acceptor bilin in phycocyanins. J. Biol. Chem. 262:6323-6327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodríguez, H., J. Rivas, M. G. Guerrero, and M. Losada. 1989. Nitrogen-fixing cyanobacterium with a high phycoerythrin content. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 55:758-760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Talarico, L., and G. Maranzana. 2000. Light and adaptive responses in red macroalgae: an overview. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 56:1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tjioe, I., T. Legerton, J. Wegstein, L. A. Herzenberg, and M. Roederer. 2001. Phycoerythrin-allophycocyanin: a resonance energy transfer fluorochrome for immunofluorescence. Cytometry 44:24-29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wiggli, M., A. Smallcombe, and R. Bachofen. 1999. Reflectance spectroscopy and laser confocal microscopy as tools in an ecophysiological study of microbial mats in an alpine bog pond. J. Microbiol. Methods 34:173-182. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wyman, M. 1992. An in vivo method for the estimation of phycoerythrin concentrations in marine cyanobacteria (Synechococcus spp.). Limnol. Oceanogr. 37:1300-1306. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ying, L., X. Huang, B. Huang, J. Xie, J. Zhao, and X. S. Zhao. 2002. Fluorescence emission and absorption spectra of single Anabaena sp. strain PCC7120 cells. Photochem. Photobiol. 76:310-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Young, A. J., and H. A. Frank. 1996. Energy transfer reactions involving carotenoids: quenching of chlorophyll fluorescence. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 36:3-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]