Abstract

The present review will give an update on temporomandibular joint (TMJ) imaging using CBCT. It will focus on diagnostic accuracy and the value of CBCT compared with other imaging modalities for the evaluation of TMJs in different categories of patients; osteoarthritis (OA), juvenile OA, rheumatoid arthritis and related joint diseases, juvenile idiopathic arthritis and other intra-articular conditions. Finally, sections on other aspects of CBCT research related to the TMJ, clinical decision-making and concluding remarks are added. CBCT has emerged as a cost- and dose-effective imaging modality for the diagnostic assessment of a variety of TMJ conditions. The imaging modality has been found to be superior to conventional radiographical examinations as well as MRI in assessment of the TMJ. However, it should be emphasized that the diagnostic information obtained is limited to the morphology of the osseous joint components, cortical bone integrity and subcortical bone destruction/production. For evaluation of soft-tissue abnormalities, MRI is mandatory. There is an obvious need for research on the impact of CBCT examinations on patient outcome.

Keywords: TMJ, CBCT, review, diagnostic imaging

Introduction

CBCT examination of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) was first reported only a couple of years after this dentomaxillofacial imaging modality was launched in the literature.1,2 The diagnostic potential of CBCT vs conventional radiographic examinations was suggested in three cases of different conditions; intra-articular fractures, osteoarthritis (OA) and fibro-osseous ankylosis.3 3 years later, another case report indicated its value in the assessment of early and late OA, as well as hypoplasia of the TMJ.4

Available literature on CBCT has become extensive since then, including reviews for application to the TMJ.5–8 The present overview will give an update on TMJ imaging using CBCT and its diagnostic value compared with other imaging modalities, with main sections on diagnostic accuracy and OA. The usefulness of CBCT in the diagnostic assessment of other TMJ conditions will be shortly reviewed. Finally, sections on clinical decision-making and concluding remarks are added.

Diagnostic accuracy

A number of studies investigating the diagnostic accuracy of CBCT dedicated to the TMJ are available. As far as we know, the first accuracy study was published in 2005, demonstrating that CBCT provided accurate and reliable linear measurements of TMJ dimensions of dry human skulls.9 The accuracy of CBCT in the assessment of TMJ dimensions was confirmed in a more recent study, concluding that the measurements of the joint spaces were very similar to the actual joint spaces.10

In 2006, it was shown that CBCT had a sensitivity of 0.80 for detecting erosions/osteophytes in an autopsy material with macroscopic observations as the gold standard.11 In the same study, CBCT was compared with multislice or multidetector CT, hereafter called CT, and although the latter had a slightly inferior sensitivity (0.70), no significant differences were found between the two modalities. In a larger series of dry human skulls comparing CBCT with conventional (spiral) tomography in 2007, a significantly lower sensitivity was found for depicting cortical defects and osteophytes, but no significant differences between the modalities were observed.12 Another dry skull study in the same year showed that CBCT provided superior reliability and greater accuracy than conventional (linear) tomography and panoramic radiography in depicting condylar cortical erosions.13

A more recent study of a dry human skull material substantiated the observation of Honda et al11 with no significant differences between CBCT and CT for detecting surface osseous changes.14 However, the sensitivities were found to be lower and thus in accordance with Hintze et al.12

The fact that CBCT has a diagnostic accuracy comparable with CT11,14 was confirmed when assessing condylar fractures in an experimental study on sheep.15

The sensitivity of CBCT for assessing bone defects is dependent on the size of the defects, as demonstrated by Marques et al16 and confirmed by Patel et al17 in their investigations of simulated condylar lesions. Extremely small defects, that is, <2 mm, proved to be difficult to detect,17 although the sensitivity for detecting condylar osseous defects overall was fairly high: 72.9–87.5%. These measurements corroborated those reported by Marques et al,16 but they substantially exceeded those reported by Hintze et al,12 who investigated morphological changes such as condylar flattening and osteophytes. It is thus suggested that erosion of the condylar surface may be easier to detect from CBCT images than other morphologic changes.17

The diagnostic accuracy of erosive changes in the TMJ has been shown to be influenced by the imaging protocol in some studies17,18 but not in others.19,20 Dry human skulls were scanned with large view and standard view protocols by Zhang et al,19 who found no significant difference between the examinations for the presence or absence of defects on the surface of the condyles. Both scanning protocols were reliable, with areas under the receiver operating characteristic curves being 0.739 and 0.720, respectively. Since the large view protocol had an effective radiation dose of only about one-sixth of the standard view protocol, the large view protocol was recommended for the assessment of TMJ conditions.19

In another study by the same authors using the same in vitro material, no significant differences were found, neither with normal nor high resolution.20 However, they also concluded that the accuracy of detecting condylar defects highly depends on the CBCT unit used for examination. Comparing different fields of view, 12, 9 and 6 inches with voxel sizes of 0.4, 0.3 and 0.2 mm, respectively, the highest diagnostic efficacy for depicting condylar erosions was found with the smallest field of view.18 In another study comparing CBCT scans with different voxel sizes (0.4 and 0.2 mm) for assessing simulated defects in fresh pig mandibular condyles, the sensitivity improved significantly for small (but not for large) defects with the increase of scanning resolution.17 Approximately one out of three small defects (both diameter and depth <2 mm) might be missed from diagnosis when using 0.4-mm voxel size CBCT scans. Using a higher scan resolution (0.2-mm voxel size), the defects, regardless of size, were detected with >80% sensitivity.17

Also in this study, it was emphasized, supporting the study by Zhang et al,20 that the data obtained with a particular CBCT scanner cannot automatically be applied to other CBCT scanners.

An interesting study compared conventional tomography, CT and CBCT with micro-CT and microscopic observations and concluded that CBCT most accurately depicted erosive changes of the bone cortex of the mandibular condyle. The high detectability of CBCT images on bone morphology of mandibular condyles was confirmed.21

In summary, CBCT in general has an acceptable accuracy for diagnosing osseous TMJ abnormalities with fairly high sensitivity, although small abnormalities might be missed. However, there are differences between different CBCT scanners and imaging protocols. In most studies, high specificity is reported. The diagnostic accuracy of CBCT seems to be comparable with CT for TMJ diagnostics.

Observer variation has been studied by several authors and in general seems to be acceptable. The observer agreement may be higher with smaller fields of view, and observers are also influenced by the size of bone defects. The smaller the defect, the more difficult its identification will be, with a lower percentage of observer agreement.

Osteoarthritis

The most common joint disease that may occur in any joint, including the TMJ, is OA. Earlier it was primarily considered a non-inflammatory disease,22 but newer research on OA in general has demonstrated that this is an inflammatory condition involving all components of the joint.23–25 Therefore, in the present review, we use the term OA in accordance with its use in medical literature, in a comprehensive, interdisciplinary textbook on temporomandibular disorders (TMDs)26 and in a comprehensive article on image analysis related to research diagnostic criteria/TMD.27 It should be mentioned that degenerative joint disease, osteoarthrosis and OA all are terms applied in the newly revised diagnostic criteria/TMD.28,29

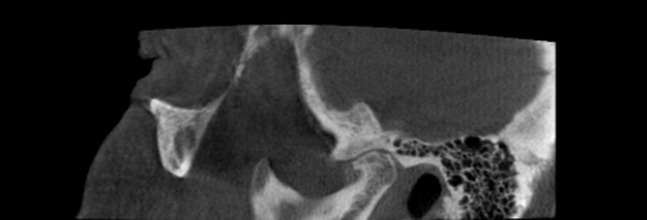

Other imaging modalities have long been used for osseous evaluation of the TMJ, as reviewed by Larheim.30 CT was found to be superior to hypocycloidal tomography for evaluating bone details in patients with rheumatic TMJ disease.31 A systematic review, however, concluded that CT did not add any significant information to what was obtained with conventional tomography regarding erosions and osteophytes.32 CT has also been compared with MRI for the assessment of cortical bone abnormalities in an autopsy study, concluding that CT was the superior modality.33 This was substantiated in a clinical study comparing CBCT and MRI.34 From these comparison studies and the accuracy studies in the previous section, it is clear that CBCT and CT are highly comparable regarding evaluation of the cortical bone. Thus, CBCT or CT is the method of choice, depending on the availability, for the assessment of cortical bone details of the TMJ because of the multiplanar reformation capabilities and high spatial resolution. This was also the conclusion made by Ahmad et al27 in their comprehensive investigation of image criteria for TMJ OA, comparing CT, MRI and panoramic radiography. Moreover, they found that interobserver agreement of calibrated observers was close to excellent for CT and only fair for MRI using kappa statistics. With comparable accuracy and observer agreement the dose- and cost-effective modality, i.e. CBCT, should be preferred. However, CBCT is more sensitive to patient motion than CT, making the diagnostic assessment of small cortical abnormalities uncertain (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

CBCT of normal temporomandibular joint with motion artefact simulating osteophyte and remodeling (double contour) (female, 75 years).

CT signs of TMJ OA were reported early in the 1980s,35 and CT criteria for the diagnosis were suggested by Koyama et al.36 Comprehensive and well-defined image criteria for OA were given by Ahmad et al27; osteophyte: marginal hypertrophy with sclerotic borders and exophytic angular formation of osseous tissue arising from the surface; subcortical sclerosis: any increased thickness of cortical plate in load-bearing areas relative to adjacent non load-bearing areas; subcortical cyst: a cavity below the articular surface that deviates from normal marrow pattern; surface erosion: loss of continuity of articular cortex; articular surface flattening: a loss of the rounded contour of the surface; and generalized sclerosis: no clear trabecular orientation with no delineation between the cortical layer and the trabecular bone that extends throughout the condylar head. Although these definitions are made for CT images, they are equally valuable for CBCT images.

No attempts were made to grade the extent of OA by Ahmad et al.27 Another challenge is the differentiation between morphological variations of normalcy and small pathological changes such as between subtle “beaking” of the anterior aspect of the condyle and small osteophyte (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

CBCT of beaking of anterior aspect of condyle—remodeling or small osteophyte? (female, 61 years).

For other joints in the body, the image appearance of OA is characterized by joint space narrowing and bone proliferation, that is, osteophyte formation and bone sclerosis, as well as subchondral cysts. Erosions are not typical37 but may be found, such as in knee OA.38,39

OA in the TMJ is also characterized by bone proliferation, but erosion is a feature as well,36,40–42 as illustrated in Figure 3. If bone destruction is prominent with little or no bone proliferation, the diagnosis will be erosive OA.43 Such a condition can hardly be distinguished from rheumatoid arthritis (RA) or another inflammatory arthritis.

Figure 3.

CBCT of osteoarthritis: osteophyte, sclerosis, flat articular surfaces, erosion and possible subchondral cyst (female, 68 years).

Joints with articular surfaces that were smooth in outline and with some flattening and/or sclerosis were interpreted as indeterminate for OA by Ahmad et al.27 The present authors have experience with CT of healthy volunteers demonstrating areas of idiopathic sclerosis that actually can be quite obvious.43 Thus, sclerosis should be interpreted with caution if it is not occurring on articulating surfaces or together with other signs indicating pathology. Joints with a condylar shape that clearly deviate from the rounded “normal” appearance but with a smooth cortical outline without evidence of osteophyte, sclerosis, subchondral cyst or erosion and with a rather even thickness of the cortical plate, may present a diagnostic challenge. Preferably, they should be interpreted as remodelled or deformed, particularly in young patients. Such a deformed joint may be the result of previous trauma or, as reported by Arvidsson et al,44 juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

CBCT of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (female, 13 years): deformed (remodelled) right joint: rather flat fossa/eminence and condyle, without cortical erosion (upper) and normal left joint for comparison (lower).

Several investigations on CBCT-assessed OA in the TMJ are available. The first large series of patients (mean age, 48 years) appeared in 2009 and demonstrated that both the frequency and severity of OA was related to age.45 This is well-accepted knowledge from OA research. The most common radiographic findings were flattening, erosion and osteophyte, followed by sclerosis. In another study, sclerosis and erosion were most frequently observed, followed by flattening.46 In that study of 220 patients aged 11–78 years (mean, 29 years), only 1 kind of condylar change was observed in 27% (119 of 440 joints), 2 kinds in 15% and 3 kinds in 12%. Only a few joints had more than three kinds of condylar change. The most frequently observed change (68% of the joints) was posterior position of the condyle in fossa. The author concluded that with more widespread use of CBCT, more specific or detailed guidelines for OA are needed.46

In a series of 319 patients aged 10–89 years, 227 (71%) had bone changes consistent with OA.47 The prevalence increased with age (except in the oldest age group with few patients) and females had a greater pre-disposition, in accordance with the general view on OA.

One study investigated the relationship between pain and other clinical signs and symptoms, and CBCT assessed OA and found poor correlation.48 This is also in accordance with the generally accepted view. On the other hand, the clinical dysfunction index proposed by Helkimo49 was highly correlated with CBCT-assessed TMJ OA but not with joint space changes.50

A case report of osteonecrosis of the mandibular condyle demonstrated in a follow-up that a primary subchondral osseous breakdown of the condyle developed into secondary articular surface collapse and OA.51 This supports the view that osteonecrosis in the bone marrow can be a precursor of TMJ OA, similar to other joints.52

TMJ OA has also been investigated in asymptomatic patients with different dentofacial deformities showing that those with skeletal jaw discrepancies (in particular Class II patients) more frequently demonstrated OA than those without jaw discrepancies.53

In patients with OA, investigations using three-dimensional (3D) shape analysis have been performed. Quantification of 3D surface models of mandibular condyles in patients with TMJ OA and in asymptomatic subjects revealed significant differences.54 It was even suggested that the extent of resorptive changes paralleled pain severity and duration. In another study of the same group, it was found that 3D shape analysis measurements of data simulated 3- and 6-mm defects on the surface of 3D models of condyles had an acceptable accuracy. Thus, 3D shape analysis could be applied in a longitudinal clinical study of TMJ OA in patients undergoing jaw surgery.55

Two studies have investigated the thickness of the roof of the glenoid fossa by CBCT in symptomatic patients with TMD, one with and the other without TMJ OA. The study without OA showed that the thickness did not correlate with condylar morphology, gender and age of the patients.56 In the other study, the thickness did correlate with the presence of OA.57

Juvenile osteoarthritis

Although OA traditionally affects adults and elderly people, the TMJ may be also affected in adolescents and children (Figure 5). As mentioned by Nickerson and Boering58, the condition was referred to as arthrosis deformans juvenilis by Boering in 1966. He found condylar abnormalities and mandibular growth disturbances in patients below 20 years of age without any suspicion of sequel from trauma. Various terminology has been applied to the paediatric age group similar to in adults; degenerative arthritis, degenerative joint disease, osteoarthrosis and OA.59–61 In our opinion, juvenile OA (JOA) would be an appropriate term today, and this term is consistently used in the present text. The condition might potentially have an effect on mandibular growth and lead to facial deformity.60,62,63

Figure 5.

CBCT of juvenile osteoarthritis: deformed (remodelled) joint: osteophyte, sclerosis and cortical erosions (female, 13 years).

Although radiographic studies are sparse, different imaging modalities have been applied to assess JOA: plain films,59 conventional tomography60 and MRI.62,63 However, CT studies have rarely been carried out,64 and only a few CBCT studies on JOA are available. After an early case report,65 two larger studies have been published.61,66 Cho and Jung61 studied JOA in 282 children and adolescents aged 10–18 years and found that the prevalence was higher in the 181 symptomatic (26.8%) than in the 101 asymptomatic (9.9%) patients. In the other study of 386 patients with TMD aged 10–19 years and 339 asymptomatic pre-orthodontic patients with malocclusions as controls, Wang et al66 confirmed the high occurrence of JOA, which was significantly higher in the TMD group (40.7%) than in the control group (12.1%). In both studies, the occurrence of juvenile TMJ OA was higher in females than in males in the patient groups, but there were no differences between the genders in the control groups.

In another CBCT study of young asymptomatic post-orthodontic subjects aged 12–20 years, Ikeda and Kawamura67 investigated the position of the condyle in the fossa and found a correlation to the position of the disc on MRI.

The condylar position and its clinical significance have been and still are a controversial subject that has attracted much attention. Many variables will influence the condylar position when CBCT is used for the TMJ examination and one should be careful to use the joint space as a diagnostic criterion, at least as the only criterion. Even in healthy children, the TMJ space is frequently asymmetric.68

In young individuals, the evaluation of the cortical bone is a greater challenge than in adults because the cortical bone will not necessarily be continuous and compact. In a CBCT study, it was concluded that the cortical bone begins to form around the periphery of the condyle during adolescence: 12–14 years.69 A continuous, homogeneous and compact cortical bone layer of the articular surface is established in young adults by the age of 21–22 years, indicating full development of the mandibular condyle.

When examining young patients, keeping a low dose is preferable. CBCT can be applied with very low exposure, and images obtained with only 2 mA can be acceptable for certain diagnostic tasks (Figure 4). However, more noisy images combined with the lack of a continuous and compact cortical layer can make the assessment of articular surfaces uncertain (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

CBCT of normal temporomandibular joint (?): non-compact, non-homogeneous cortical surface of condyle (upper), making diagnostic assessment uncertain (female, 13 years). Normal compact and homogeneous cortical outline of condyle (lower) for comparison (female, 69 years).

Bone changes in the TMJ can indicate disease (OA) and/or a remodelling process. The boundary between these conditions can be difficult to determine, especially in growing individuals where the TMJ is undergoing morphological changes. Subtle JOA may be neglected, missed or even over diagnosed.

Rheumatoid arthritis and related joint diseases

For joints in general, the hallmark of inflammation in bone as assessed from plain images and CT, is the cortical erosion (destruction).70 Thus, erosions without bone proliferation indicate inflammatory arthritis, that is, RA, which is the most frequent rheumatic disease. Multiple erosions with bone proliferation may indicate ankylosing spondylitis or psoriatic arthritis, or other seronegative spondylarthropathies.70 In the TMJ, it is not possible to differentiate between rheumatic diseases based on imaging, although the bone production seems to be more pronounced in ankylosing spondylitis; most of our TMJ ankylosis cases are in this disease group.

Typical findings in rheumatic patients with active TMJ arthritis are punched-out bone destructions (erosions), which may become quite severe (Figure 7). Both the condyle and the fossa/eminence can be involved. Osteoarthritic signs may accompany the destruction. In long-standing disease, flattening and bone-productive changes (sclerosis, osteophyte) may be more evident and the cortical erosions less pronounced. In such cases, the differentiation between OA and inflammatory arthritis with secondary OA may be impossible with CBCT used as the only imaging modality. It is the experience of the present authors that the destruction/deformation may be more pronounced in patients with a rheumatic disease.

Figure 7.

CBCT of rheumatoid arthritis: punched-out destruction with sclerosis (female, 59 years).

Little research on CBCT and RA is available. Hajati et al71 found that a majority of patients with early RA showed radiographic signs of bone destructions in the TMJ, and that plasma levels of glutamate were associated with the extent of these changes.

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis

Rheumatic disease may also occur in childhood, and JIA is the most frequent inflammatory musculoskeletal disease in patients younger than 16 years of age. TMJ affection may lead to typical facial growth deformities.72,73 Most large studies of children with JIA indicate that nearly half of the children will have radiographical TMJ abnormalities, although MRI studies with fewer patients have shown much higher frequencies.74 The joints are characterized by deformation and may show a highly variable morphology.44 Flattening of the condyle and fossa/eminence and widening of the fossa as well as the condyle anteroposteriorly are typical findings (Figure 8). Without bone erosions, the deformations may be considered growth disturbances of the joint (Figure 4) or a result of previous erosions with subsequent remodelling/“healing”.44 Erosions may be present in active periods of the disease but should not be confused with non-homogeneous and non-compact cortex of the condyle seen in healthy growing children.69 It is well known that symptoms and clinical signs of TMJ involvement may be subtle, making imaging an important diagnostic tool.75–77

Figure 8.

CBCT of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: deformed (remodelled) joint with surface erosions: flattened condyle with enlarged anteroposterior dimension and double contour. Articular eminence also flattened (female, 16 years).

Some CBCT studies of patients with JIA are available. A clinical evaluation according to the research diagnostic/TMD criteria78 revealed only a few of the patients with JIA with TMJ bone abnormalities on CBCT.79 CBCT was used to measure condylar volume or 3D asymmetry in patients with JIA.80,81 It was also applied to patients with unilateral TMJ involvement undergoing splint therapy to reduce the mandibular asymmetry.82 A grading system for TMJ JIA has recently been suggested, using a combination of CBCT and MRI findings.83

Other intra-articular disorders

CBCT was applied in a series of 34 cases of osteochondroma of the mandibular condyle,84 and in a case report,85 both studies emphasized the value of 3D reconstructions when viewing expansive lesions. The imaging modality has also been applied to a series of 27 cases with facial asymmetry and condylar hyperplasia.86 In addition, reports of cases have been published, such as synovial chondromatosis,87,88 fibrous ankylosis in RA89 and metastasis of a bronchial carcinoma.90 Similar rare conditions have been illustrated in previously mentioned review articles,5,6 which also showed trauma and developmental cases. Condylar fractures can be nicely demonstrated with CBCT (Figure 9) and so can developmental anomalies (Figure 10). In patients with facial deformities, both the TMJ and the facial skeleton abnormalities can be visualized with CBCT scanning, depending on the field of view.

Figure 9.

CBCT of intra-articular fractures. Reproduced from Larheim and Westesson91 with permission from Springer.

Figure 10.

CBCT of developmental anomaly, probably hemifacial microsomia (male, 8 years). Abnormal condyle morphology and condyle location, lack of fossa/eminence development and enlarged coronoid process (upper, middle). For comparison, normal contralateral joint (lower).

Miscellaneous

Several investigations using 3D analysis of the mandibular condyle are available. The volume and surface of condyles from young adult subjects without pain or TMD have been reported as values of normal TMJs for future 3D comparative studies.92 The reliability of regional 3D registration and superimposition methods for the assessment of mandibular condyle morphology, across subjects and longitudinally, has been found to be acceptable.93 The authors claim that subtle bony differences in 3D condylar morphology can be quantified. The method was applied to assess changes in condylar 3D morphology in patients who underwent maxillomandibular advancement with and without simultaneous disc repositioning. Those with disc repositioning showed evident condylar bone apposition, in contrast to those with maxillomandibular advancement without disc repositioning.94

The normal standards for position of the mandibular condyle in the fossa has also been investigated. The condylar position was assessed in asymptomatic subjects both in oblique sagittal images95 and in oblique coronal and axial images,96 providing norms for 3D assessment in healthy individuals.

Pneumatization of the temporal bone may be a diagnostic challenge for the assessment of cortical erosions in the articular eminence if they reach the articular surface, and CBCT is the superior method to depict such anatomic variations.97

CBCT has been applied in the evaluation of bifid mandibular condyles,98,99 coronoid hyperplasia100 and articular eminence morphology101–103 and to assess condylar remodelling accompanying splint therapy.104

The superior semi-circular canal of the vestibulum system was investigated in patients with TMJ symptoms suggesting a possible relationship between a specific morphological pattern; the dehiscence of its roof and symptoms.105 The maxillofacial radiologist should be aware of this anatomic structure.

A method based on the registration of single-plane fluoroscopy images and 3D low-radiation CBCT data has also been proposed to quantify 3D mandibular motion (TMJ and chewing function).106

CBCT has also been found useful as an image-guided technique for safe puncturing of the superior TMJ space.107 This procedure proved effective for pain mitigation and improved mouth opening during the early post-operative period after pumping manipulation treatment.108

Clinical decision-making

Although the literature on TMJ diagnostics using CBCT has become rather extensive, the current available data seem to be limited to the first two levels in the six-stage framework to assess the efficacy of imaging methods as defined by Fryback and Thornbury:109 technical efficacy and diagnostic accuracy efficacy. Little attention has been paid to the next two levels, diagnostic thinking efficacy and therapeutic efficacy. This is particularly important in the evaluation of patients with TMD, being the largest group of patients undergoing TMJ imaging procedures.

To the best of our knowledge only one study has focused on the value of CBCT examinations in clinical decision-making; primary diagnosis and management of patients with TMD. The clinical decision changed in more than half of the patients when it was based on physical, panoramic and CBCT examinations compared with a decision based on physical and panoramic examinations only.110 Thus, the usefulness of CBCT in patient management was clearly demonstrated.

Concluding remarks

In a relatively short period of time, CBCT has emerged as a cost- and dose-effective alternative to CT for examination of the TMJs, although it may be more sensitive to motion artefacts. The imaging modality is superior to conventional radiographic methods, as well as MRI, in the assessment of osseous TMJ abnormalities. However, it should be emphasized that the diagnostic information obtained is limited to the morphology of the osseous joint components, cortical bone integrity and subcortical osseous abnormalities. For the assessment of inflammatory activity and soft-tissue abnormalities such as internal derangement in patients with TMD, MRI is the method of choice. There is a lack of knowledge about the impact of CBCT examinations on patient outcome and thus an obvious need for research in this area.

References

- 1.Mozzo P, Procacci C, Tacconi A, Martini PT, Andreis IA. A new volumetric CT machine for dental imaging based on the cone-beam technique: preliminary results. Eur Radiol 1998; 8: 1558–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arai Y, Tammisalo E, Iwai K, Hashimoto K, Shinoda K. Development of a compact computed tomographic apparatus for dental use. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 1999; 28: 245–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Honda K, Larheim TA, Johannessen S, Arai Y, Shinoda K, Westesson PL. Ortho cubic super-high resolution computed tomography: a new radiographic technique with application to the temporomandibular joint. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2001; 91: 239–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsiklakis K, Syriopoulos K, Stamatakis HC. Radiographic examination of the temporomandibular joint using cone beam computed tomography. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2004; 33: 196–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsiklakis K. Cone beam computed tomographic findings in temporomandibular joint disorders. Alpha Omegan 2010; 103: 68–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barghan S, Tetradis S, Mallya S. Application of cone beam computed tomography for assessment of the temporomandibular joints. Aust Dent J 2012; 57: 109–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2011.01663.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hunter A, Kalathingal S. Diagnostic imaging for temporomandibular disorders and orofacial pain. Dent Clin North Am 2013; 57: 405–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2013.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krishnamoorthy B, Mamatha N, Kumar VA. TMJ imaging by CBCT: current scenario. Ann Maxillofac Surg 2013; 3: 80–3. doi: 10.4103/2231-0746.110069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hilgers ML, Scarfe WC, Scheetz JP, Farman AG. Accuracy of linear temporomandibular joint measurements with cone beam computed tomography and digital cephalometric radiography. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2005; 128: 803–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang ZL, Cheng JG, Li G, Zhang JZ, Zhang ZY, Ma XC. Measurement accuracy of temporomandibular joint space in Promax 3-dimensional cone-beam computerized tomography images. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2012; 114: 112–17. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2011.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Honda K, Larheim TA, Maruhashi K, Matsumoto K, Iwai K. Osseous abnormalities of the mandibular condyle: diagnostic reliability of cone beam computed tomography compared with helical computed tomography based on an autopsy material. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2006; 35: 152–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hintze H, Wiese M, Wenzel A. Cone beam CT and conventional tomography for the detection of morphological temporomandibular joint changes. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2007; 36: 192–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Honey OB, Scarfe WC, Hilgers MJ, Klueber K, Silveira AM, Haskell BS, et al. Accuracy of cone-beam computed tomography imaging of the temporomandibular joint: comparisons with panoramic radiology and linear tomography. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2007; 132: 429–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zain-Alabdeen EH, Alsadhan RI. A comparative study of accuracy of detection of surface osseous changes in the temporomandibular joint using multidetector CT and cone beam CT. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2012; 41: 185–91. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/24985981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sirin Y, Guven K, Horasan S, Sencan S. Diagnostic accuracy of cone beam computed tomography and conventional multislice spiral tomography in sheep mandibular condyle fractures. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2010; 39: 336–42. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/29930707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marques AP, Perrella A, Arita ES, Pereira MF, Cavalcanti Mde G. Assessment of simulated mandibular condyle bone lesions by cone beam computed tomography. Braz Oral Res 2010; 24: 467–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel A, Tee BC, Fields H, Jones E, Chaudhry J, Sun Z. Evaluation of cone-beam computed tomography in the diagnosis of simulated small osseous defects in the mandibular condyle. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2014; 145: 143–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2013.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Librizzi ZT, Tadinada AS, Valiyaparambil JV, Lurie AG, Mallya SM. Cone-beam computed tomography to detect erosions of the temporomandibular joint: effect of field of view and voxel size on diagnostic efficacy and effective dose. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2011; 140: e25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2011.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang ZL, Cheng JG, Li G, Shi XQ, Zhang JZ, Zhang ZY, et al. Detection accuracy of condylar bony defects in promax 3D cone beam CT images scanned with different protocols. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2013; 42: 20120241. doi: 10.1259/dmfr.20120241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang ZL, Shi XQ, Ma XC, Li G. Detection accuracy of condylar defects in cone beam CT images scanned with different resolutions and units. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2014; 43: 20130414. doi: 10.1259/dmfr.20130414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katakami K, Shimoda S, Kobayashi K, Kawasaki K. Histological investigation of osseous changes of mandibular condyles with backscattered electron images. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2008; 37: 330–9. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/93169617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Resnick D. Common disorders of synovium-lined joints: pathogenesis, imaging abnormalities, and complications. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1988; 151: 1079–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berenbaum F. Osteoarthritis as an inflammatory disease (osteoarthritis is not osteoarthrosis!). Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2013; 21: 16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wenham CY, Conaghan PG. New horizons in osteoarthritis. Age Ageing 2013; 42: 272–8. doi: 10.1093/ageing/aft043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Felson DT. Osteoarthritis: priorities for osteoarthritis research: much to be done. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2014; 10: 447–8. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2014.76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laskin DM, Greene CS, Hylander WL, eds. Temporomandibular disorders: an evidence-based approach to diagnosis and treatment. Chicago, IL: Quintessence Publishing Co Inc.; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahmad M, Hollender L, Anderson Q, Kartha K, Ohrbach R, Truelove EL, et al. Research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders (RDC/TMD): development of image analysis criteria and examiner reliability for image analysis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2009; 107: 844–60. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.02.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schiffman E, Ohrbach R, Truelove E, Look J, Anderson G, Goulet JP, et al. ; International RDC/TMD Consortium Network, International association for Dental Research Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group, International Association for the Study of Pain. Diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders (DC/TMD) for clinical and research applications: recommendations of the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network* and Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group†. J Oral Facial Pain Headache 2014; 28: 6–27. doi: 10.11607/jop.1151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peck CC, Goulet JP, Lobbezoo F, Schiffman EL, Alstergren P, Anderson GC, et al. Expanding the taxonomy of the diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders. J Oral Rehabil 2014; 41: 2–23. doi: 10.1111/joor.12132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Larheim TA. Current trends in temporomandibular joint imaging. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1995; 80: 555–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Larheim TA, Kolbenstvedt A. Osseous temporomandibular joint abnormalities in rheumatic disease. Computed tomography versus hypocycloidal tomography. Acta Radiol 1990; 31: 383–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hussain AM, Packota G, Major PW, Flores-Mir C. Role of different imaging modalities in assessment of temporomandibular joint erosions and osteophytes: a systematic review. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2008; 37: 63–71. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/16932758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Westesson PL, Katzberg RW, Tallents RH, Sanchez-Woodworth RE, Svensson SA. CT and MR of the temporomandibular joint: comparison with autopsy specimens. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1987; 148: 1165–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alkhader M, Kuribayashi A, Ohbayashi N, Nakamura S, Kurabayashi T. Usefulness of cone beam computed tomography in temporomandibular joints with soft tissue pathology. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2010; 39: 343–8. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/76385066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Larheim TA, Kolbenstvedt A. High-resolution computed tomography of the osseous temporomandibular joint. Some normal and abnormal appearances. Acta Radiol Diagn (Stockh) 1984; 25: 465–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koyama J, Nishiyama H, Hayashi T. Follow-up study of condylar bony changes using helical computed tomography in patients with temporomandibular disorder. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2007; 36: 472–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jacobson JA, Girish G, Jiang Y, Sabb BJ. Radiographic evaluation of arthritis: degenerative joint disease and variations. Radiology 2008; 248: 737–47. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2483062112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pattrick M, Hamilton E, Wilson R, Austin S, Doherty M. Association of radiographic changes of osteoarthritis, symptoms, and synovial fluid particles in 300 knees. Ann Rheum Dis 1993; 52: 97–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Derek T, Cooke V, Kelly BP, Harrison L, Mohamed G, Khan B. Radiographic grading for knee osteoarthritis. A revised scheme that relates to alignment and deformity. J Rheumatol 1999; 26: 641–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Akerman S, Kopp S, Rohlin M. Macroscopic and microscopic appearance of radiologic findings in temporomandibular joints from elderly individuals. An autopsy study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1988; 17: 58–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsuruta A, Yamada K, Hanada K, Hosogai A, Tanaka R, Koyama J, et al. Thickness of the roof of the glenoid fossa and condylar bone change: a CT study. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2003; 32: 217–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rudisch A, Emshoff R, Maurer H, Kovacs P, Bodner G. Pathologic-sonographic correlation in temporomandibular joint pathology. Eur Radiol 2006; 16: 1750–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Larheim TA. Diagnostic imaging of the TMJ. In: Oral and maxillofacial surgery knowledge update 2014, volume V (OMSKU V) (Busaidy KF, ed.). Available from: http://aaoms2.centrax.com/?page_id=821 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arvidsson LZ, Smith HJ, Flato B, Larheim TA. Temporomandibular joint findings in adults with long-standing juvenile idiopathic arthritis: CT and MR imaging assessment. Radiology 2010; 256: 191–200. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10091810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alexiou K, Stamatakis H, Tsiklakis K. Evaluation of the severity of temporomandibular joint osteoarthritic changes related to age using cone beam computed tomography. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2009; 38: 141–7. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/59263880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nah KS. Condylar bony changes in patients with temporomandibular disorders: a CBCT study. Imaging Sci Dent 2012; 42: 249–53. doi: 10.5624/isd.2012.42.4.249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.dos Anjos Pontual ML, Freire JS, Barbosa JM, Frazao MA, dos Anjos Pontual A. Evaluation of bone changes in the temporomandibular joint using cone beam CT. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2012; 41: 24–9. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/17815139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Palconet G, Ludlow JB, Tyndall DA, Lim PF. Correlating cone beam CT results with temporomandibular joint pain of osteoarthritic origin. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2012; 41: 126–30. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/60489374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Helkimo M. Studies on function and dysfunction of the masticatory system. II. Index for anamnestic and clinical dysfunction and occlusal state. Sven Tandlak Tidskr 1974; 67: 101–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Su N, Liu Y, Yang X, Luo Z, Shi Z. Correlation between bony changes measured with cone beam computed tomography and clinical dysfunction index in patients with temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2014; 42: 1402–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2014.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fu KY, Li YW, Zhang ZK, Ma XC. Osteonecrosis of the mandibular condyle as a precursor to osteoarthrosis: a case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2009; 107: e34–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Larheim TA, Westesson PL, Hicks DG, Eriksson L, Brown DA. Osteonecrosis of the temporomandibular joint: correlation of magnetic resonance imaging and histology. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1999; 57: 888–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Krisjane Z, Urtane I, Krumina G, Neimane L, Ragovska I. The prevalence of TMJ osteoarthritis in asymptomatic patients with dentofacial deformities: a cone-beam CT study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2012; 41: 690–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2012.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cevidanes LH, Hajati AK, Paniagua B, Lim PF, Walker DG, Palconet G, et al. Quantification of condylar resorption in temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2010; 110: 110–17. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2010.01.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Paniagua B, Cevidanes L, Walker D, Zhu H, Guo R, Styner M. Clinical application of SPHARM-PDM to quantify temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis. Comput Med Imaging Graph 2011; 35: 345–52. doi: 10.1016/j.compmedimag.2010.11.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kijima N, Honda K, Kuroki Y, Sakabe J, Ejima K, Nakajima I. Relationship between patient characteristics, mandibular head morphology and thickness of the roof of the glenoid fossa in symptomatic temporomandibular joints. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2007; 36: 277–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ejima K, Schulze D, Stippig A, Matsumoto K, Rottke D, Honda K. Relationship between the thickness of the roof of glenoid fossa, condyle morphology and remaining teeth in asymptomatic European patients based on cone beam CT data sets. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2013; 42: 90929410. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/90929410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nickerson JW, Boering G. Natural course of osteoarthrosis as it relates to internal derangement of the temporomandibular joint. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am 1989; 1: 27–45. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ogus H. Degenerative disease of the temporomandibular joint in young persons. Br J Oral Surg 1979; 17: 17–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Katzberg RW, Tallents RH, Hayakawa K, Miller TL, Goske MJ, Wood BP. Internal derangements of the temporomandibular joint: findings in the pediatric age group. Radiology 1985; 154: 125–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cho BH, Jung YH. Osteoarthritic changes and condylar positioning of the temporomandibular joint in Korean children and adolescents. Imaging Sci Dent 2012; 42: 169–74. doi: 10.5624/isd.2012.42.3.169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schellhas KP, Piper MA, Omlie MR. Facial skeleton remodeling due to temporomandibular joint degeneration: an imaging study of 100 patients. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1990; 11: 541–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Westesson PL, Tallents RH, Katzberg RW, Guay JA. Radiographic assessment of asymmetry of the mandible. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1994; 15: 991–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yamada K, Saito I, Hanada K, Hayashi T. Observation of three cases of temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis and mandibular morphology during adolescence using helical CT. J Oral Rehabil 2004; 31: 298–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sakabe R, Sakabe J, Kuroki Y, Nakajima I, Kijima N, Honda K. Evaluation of temporomandibular disorders in children using limited cone-beam computed tomography: a case report. J Clin Pediatr Dent 2006; 31: 14–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang ZH, Jiang L, Zhao YP, Ma XC. Investigation on radiographic signs of osteoarthrosis in temporomandibular joint with cone beam computed tomography in adolescents. [In Chinese.] J Peking Univ Health Sci 2013; 45: 280–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ikeda K, Kawamura A. Disc displacement and changes in condylar position. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2013; 42: 84227642. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/84227642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Larheim TA. Temporomandibular joint space in children without joint disease. Acta Radiol Diagn (Stockh) 1981; 22: 85–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lei J, Liu MQ, Yap AU, Fu KY. Condylar subchondral formation of cortical bone in adolescents and young adults. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2013; 51: 63–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2012.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jacobson JA, Girish G, Jiang Y, Resnick D. Radiographic evaluation of arthritis: inflammatory conditions. Radiology 2008; 248: 378–89. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2482062110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hajati AK, Alstergren P, Nasstrom K, Bratt J, Kopp S. Endogenous glutamate in association with inflammatory and hormonal factors modulates bone tissue resorption of the temporomandibular joint in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2009; 67: 1895–903. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.04.056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Arvidsson LZ, Fjeld MG, Smith HJ, Flatø B, Ogaard B, Larheim TA. Craniofacial growth disturbance is related to temporomandibular joint abnormality in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis, but normal facial profile was also found at the 27-year follow-up. Scand J Rheumatol 2010; 39: 373–9. doi: 10.3109/03009741003685624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fjeld M, Arvidsson L, Smith HJ, Flatø B, Ogaard B, Larheim T. Relationship between disease course in the temporomandibular joints and mandibular growth rotation in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis followed from childhood to adulthood. Pediatr Rheumatology Online J 2010; 8: 13. doi: 10.1186/1546-0096-8-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Larheim TA, Doria AS, Kirkhus E, Parra DA, Kellenberger CJ, Arvidsson LZ. TMJ imaging in JIA patients—an overview. Semin Orthod 2015; in press.

- 75.Larheim TA, Hoyeraal HM, Stabrun AE, Haanaes HR. The temporomandibular joint in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Radiographic changes related to clinical and laboratory parameters in 100 children. Scand J Rheumatol 1982; 11: 5–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Arabshahi B, Cron RQ. Temporomandibular joint arthritis in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: the forgotten joint. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2006; 18: 490–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Twilt M, Schulten AJ, Verschure F, Wisse L, Prahl-Andersen B, van Suijlekom-Smit LW. Long-term followup of temporomandibular joint involvement in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2008; 59: 546–52. doi: 10.1002/art.23532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dworkin SF, LeResche L. Research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders: review, criteria, examinations and specifications, critique. J Craniomandib Disord 1992; 6: 301–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ferraz AM, Jr, Devito KL, Guimarães JP. Temporomandibular disorder in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: clinical evaluation and correlation with the findings of cone beam computed tomography. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2012; 114: e51–7. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2012.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Huntjens E, Kiss G, Wouters C, Carels C. Condylar asymmetry in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis assessed by cone-beam computed tomography. Eur J Orthod 2008; 30: 545–51. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjn056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Farronato G, Garagiola U, Carletti V, Cressoni P, Mercatali L, Farronato D. Change in condylar and mandibular morphology in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: cone beam volumetric imaging. [In Italian.] Minerva Stomatol 2010; 59: 519–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Stoustrup P, Kuseler A, Kristensen KD, Herlin T, Pedersen TK. Orthopaedic splint treatment can reduce mandibular asymmetry caused by unilateral temporomandibular involvement in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Eur J Orthod 2013; 35: 191–8. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjr116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Koos B, Tzaribachev N, Bott S, Ciesielski R, Godt A. Classification of temporomandibular joint erosion, arthritis, and inflammation in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Orofac Orthop 2013; 74: 506–19. doi: 10.1007/s00056-013-0166-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Meng Q, Chen S, Long X, Cheng Y, Deng M, Cai H. The clinical and radiographic characteristics of condylar osteochondroma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2012; 114: e66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2012.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Venturin JS, Shintaku WH, Shigeta Y, Ogawa T, Le B, Clark GT. Temporomandibular joint condylar abnormality: evaluation, treatment planning, and surgical approach. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2010; 68: 1189–96. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Olate S, Almeida A, Alister JP, Navarro P, Netto HD, de Moraes M. Facial asymmetry and condylar hyperplasia: considerations for diagnosis in 27 consecutives patients. Int J Clin Exp Med 2013; 6: 937–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Balasundaram A, Geist JR, Gordon SC, Klasser GD. Radiographic diagnosis of synovial chondromatosis of the temporomandibular joint: a case report. J Can Dent Assoc 2009; 75: 711–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Matsumoto K, Sato T, Iwanari S, Kameoka S, Oki H, Komiyama K, et al. The use of arthrography in the diagnosis of temporomandibular joint synovial chondromatosis. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2013; 42: 15388284. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/15388284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cunha CO, Pinto LM, de Mendonca LM, Saldanha AD, Conti AC, Conti PC. Bilateral asymptomatic fibrous-ankylosis of the temporomandibular joint associated with rheumatoid arthritis: a case report. Braz Dent J 2012; 23: 779–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Schulze D. Metastasis of a bronchial carcinoma in the left condylar process. Quintessence Int 2008; 39: 616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Larheim TA, Westesson P-LA. Maxillofacial imaging. 1st edn. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tecco S, Saccucci M, Nucera R, Polimeni A, Pagnoni M, Cordasco G, et al. Condylar volume and surface in Caucasian young adult subjects. BMC Med Imaging 2010; 10: 28. doi: 10.1186/1471-2342-10-28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Schilling J, Gomes LC, Benavides E, Nguyen T, Paniagua B, Styner M, et al. Regional 3D superimposition to assess temporomandibular joint condylar morphology. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2014; 43: 20130273. doi: 10.1259/dmfr.20130273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Goncalves JR, Wolford LM, Cassano DS, da Porciuncula G, Paniagua B, Cevidanes LH. Temporomandibular joint condylar changes following maxillomandibular advancement and articular disc repositioning. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2013; 71: 1759.e1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2013.06.209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ikeda K, Kawamura A. Assessment of optimal condylar position with limited cone-beam computed tomography. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2009; 135: 495–501. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ikeda K, Kawamura A, Ikeda R. Assessment of optimal condylar position in the coronal and axial planes with limited cone-beam computed tomography. J Prosthodont 2011; 20: 432–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-849X.2011.00730.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Miloglu O, Yilmaz AB, Yildirim E, Akgul HM. Pneumatization of the articular eminence on cone beam computed tomography: prevalence, characteristics and a review of the literature. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2011; 40: 110–4. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/75842018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Cho BH, Jung YH. Nontraumatic bifid mandibular condyles in asymptomatic and symptomatic temporomandibular joint subjects. Imaging Sci Dent 2013; 43: 25–30. doi: 10.5624/isd.2013.43.1.25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Almasan OC, Hedesiu M, Baciut G, Baciut M, Bran S, Jacobs R. Nontraumatic bilateral bifid condyle and intermittent joint lock: a case report and literature review. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2011; 69: e297–303. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.03.072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Utsman RA, Klasser GD, Padilla M. Coronoid hyperplasia in a pediatric patient: case report and review of the literature. J Calif Dent Assoc 2013; 41: 766–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sumbullu MA, Cağlayan F, Akgül HM, Yilmaz AB. Radiological examination of the articular eminence morphology using cone beam CT. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2012; 41: 234–40. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/24780643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Shahidi S, Vojdani M, Paknahad M. Correlation between articular eminence steepness measured with cone-beam computed tomography and clinical dysfunction index in patients with temporomandibular joint dysfunction. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2013; 116: 91–7. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2013.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ilguy D, Ilguy M, Fisekcioglu E, Dolekoglu S, Ersan N. Articular eminence inclination, height, and condyle morphology on cone beam computed tomography. Scientific World Journal 2014; 2014: 761714. doi: 10.1155/2014/761714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Liu MQ, Chen HM, Yap AU, Fu KY. Condylar remodeling accompanying splint therapy: a cone-beam computerized tomography study of patients with temporomandibular joint disk displacement. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2012; 114: 259–65. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2012.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kurt H, Orhan K, Aksoy S, Kursun S, Akbulut N, Bilecenoglu B. Evaluation of the superior semicircular canal morphology using cone beam computed tomography: a possible correlation for temporomandibular joint symptoms. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2014; 117: e280–8. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2014.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Chen CC, Lin CC, Chen YJ, Hong SW, Lu TW. A method for measuring three-dimensional mandibular kinematics in vivo using single-plane fluoroscopy. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2013; 42: 95958184. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/95958184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Honda K, Bjørnland T. Image-guided puncture technique for the superior temporomandibular joint space: value of cone beam computed tomography (CBCT). Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2006; 102: 281–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Matsumoto K, Bjornland T, Kai Y, Honda M, Yonehara Y, Honda K. An image-guided technique for puncture of the superior temporomandibular joint cavity: clinical comparison with the conventional puncture technique. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2011; 111: 641–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2011.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Fryback DG, Thornbury JR. The efficacy of diagnostic imaging. Med Decis Making 1991; 11: 88–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.de Boer EW, Dijkstra PU, Stegenga B, de Bont LG, Spijkervet FK. Value of cone-beam computed tomography in the process of diagnosis and management of disorders of the temporomandibular joint. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2014; 52: 241–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2013.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]