Abstract

A new protein immobilization and purification system has been developed based on the use of polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs, or bioplastics), which are biodegradable polymers accumulated as reserve granules in the cytoplasm of certain bacteria. The N-terminal domain of the PhaF phasin (a PHA-granule-associated protein) from Pseudomonas putida GPo1 was used as a polypeptide tag (BioF) to anchor fusion proteins to PHAs. This tag provides a novel way to immobilize proteins in vivo by using bioplastics as supports. The granules carrying the BioF fusion proteins can be isolated by a simple centrifugation step and used directly for some applications. Moreover, when required, a practically pure preparation of the soluble BioF fusion protein can be obtained by a mild detergent treatment of the granule. The efficiency of this system has been demonstrated by constructing two BioF fusion products, including a functional BioF-β-galactosidase. This is the first example of an active bioplastic consisting of a biodegradable matrix carrying an active enzyme.

The field of bioprocessing is experiencing a strong impetus to improve and adapt modern biotechnology to classical fermentation technologies. This stimulus has been promoted by the development of different heterologous gene expression systems, particularly by the creation of alternative protein fusion methodologies to facilitate the downstream processing of proteins after fermentation (5, 13, 25, 30). In such cases, the desired protein is fused to a specific tag that can be easily purified by affinity, ion-exchange, hydrophobic, covalent, or metal-chelation chromatography. Nevertheless, several of the tag systems that are currently on the market involve expensive purification processes which are mainly applied to high-value products (13). Therefore, we have dedicated our efforts to finding and developing new tags that can offer new advantages, e.g., low-cost processing, in vivo immobilization, support biodegradability, etc., and that can be used for a large variety of proteins.

Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs), also commonly known as bioplastics, are biodegradable polymers produced by certain bacteria that are accumulated as reserve granules in the cytoplasm when the culture conditions are not optimal for growing (16, 27). The PHA granules contain phospholipid-coated polyesters and granule-associated proteins (GAPs) at their surfaces (28). To date, four classes of GAPs have been defined for bacteria: (i) PHA synthases, involved in the polymerization of PHAs; (ii) PHA depolymerases, responsible for bioplastic degradation; (iii) phasins, the main components of GAPs; and (iv) other proteins (28). Phasins have been identified in several microorganisms (14, 17, 21, 22, 26, 31) and are thought to fulfill a similar function to that of oleosins in pollen and seed plants, generating an interphase between the cytoplasm and the hydrophobic core of PHA granules (28). In the case of medium-chain-length PHA granules (mclPHA), formed by hydroxyalkanoic acid monomers consisting of 6 to 14 carbon atoms, it has been suggested that the surface of the granule is shaped by two distinct protein layers separated by a phospholipid layer (6, 29). Members of our laboratory recently demonstrated that the mclPHA granules of Pseudomonas putida GPo1 contain two phasins, of 15.4 kDa (PhaI) and 26.3 kDa (PhaF), and showed that PhaF behaves not only as a structural protein but also as a transcriptional regulator of the biosynthetic pha cluster (22). Remarkably, the C-terminal region of PhaF is similar to that of histone-like proteins, whereas the N-terminal region has a 57% similarity with the complete PhaI phasin (22). Since both phasins are attached to the granule, it was postulated that the N-terminal region of PhaF might be responsible for attachment to PHA granules (22).

In this work, we demonstrate that the N-terminal region of PhaF certainly behaves as a functional domain that is able to bind PHA granules. Furthermore, we describe the use of this N-terminal region of PhaF as a polypeptide tag (BioF) that is capable of binding to bioplastic granules and coprecipitates with them in a simple centrifugation process. The utility of this property is demonstrated by the construction of different fully functional chimeric proteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, plasmids, and DNA manipulations.

The strains and plasmids used for this study are listed in Table 1. A 465-bp DNA fragment containing the BioF tag (nucleotides 1465 to 1890 of phaF [accession number AJ01393]) was amplified by a PCR using plasmid pPF3 (22) as the DNA template and the primers NF1 (5′-GCTCTAGAGGGTATTAATAaTGGCTGGCAAGAAGAATTCCGAGAAAGAAGGC-3′) (the XbaI site is underlined, and the first nucleotide that forms part of the phaF gene is indicated in lowercase) and CF1 (5′-AAAAAAAAAGCTTAGATATCgCGCGACGAAATCGGGGTAAC-3′) (the HindIII and EcoRV sites are underlined, and the last nucleotide belonging to the phaF coding region is indicated in lowercase). The bioF DNA fragment was inserted, after digestion with the XbaI and HindIII endonucleases, into the pUC18 vector to yield the plasmid pNF1. The 3′-truncated lytA gene was cloned into pUC18 by HincII-HindIII digestion of pGL80 (7), creating pULA3. For each PCR amplification, we used 10 ng of template plasmid DNA. The conditions for amplification were chosen according to the G+C content of the corresponding oligonucleotides.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Revelant genotype or phenotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| P. putida | ||

| GPo1 | OCT PHA, ATCC 29347 | 32 |

| GPG-Tc6 | GPo1 derivative, Tcr Kmr PcI::lacZ phaF::mini-Tn5Tc | 22 |

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | Host for E. coli plasmids | 24 |

| CC118(λ-pir) | Host for pVLT35-derived plasmids | 9 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pUC18 | Apr, cloning vector | 24 |

| pVLT35 | SmrlacIq, vector to express hybrid genes | 1 |

| pPF3 | Apr, pUCNot derivative, phaF and phaI from P. putida GPo1 | 22 |

| pUJ9 | Apr, promoterless lacZ vector | 2 |

| pGL80 | Apr Cmr, pBR325 derivative, lytA | 7 |

| pNF1 | Apr, pUC18 derivative, bioF | This study |

| pULA3 | pUC18 derivative, 3′-lytA | This study |

| pNFA1 | pNF1 derivative, flyt | This study |

| pNFA2 | pVLT35 derivative, flyt | This study |

| pNFL1 | pNF1 derivative, flac | This study |

| pNFL2 | pVLT35 derivative, flac | This study |

Growth conditions, granule isolation, and analysis of GAPs.

Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas strains were cultivated in Luria-Bertani medium (24) with aeration at 37 and 30°C, respectively. For PHA production, Pseudomonas strains were grown as described previously (32), using 0.1 N M63 medium, which is a nitrogen-limited minimal medium [13.6 g of KH2PO4/liter, 0.2 g of (NH4)2SO4/liter, 0.5 mg of FeSO4 · 7H2O/liter, adjusted to pH 7 with KOH], plus 15 mM octanoic acid. Growth was monitored with a Shimadzu UV-260 spectrophotometer at 600 nm. Cells were broken by a fourfold passage through a French press (1,000 lb/in2). Antibiotics were added to the growth medium to the following final concentrations: ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; tetracycline, 12.5 μg/ml; kanamycin, 50 μg/ml; streptomycin, 200 μg/ml; and chloramphenicol, 30 μg/ml. The transformation of E. coli cells was carried out by the RbCl method or by electroporation (Gene Pulser; Bio-Rad) (3). Plasmid transference to the target Pseudomonas strains was done by the filter-mating technique (9). Granule isolation was done either by ultracentrifugation through a sucrose gradient (110,000 × g for 3.5 h) (11), by centrifugation (12,000 × g for 30 min) onto 55% glycerol (18), or by simple centrifugation (4,000 × g for 30 min) of total crude extracts kept at 4°C during the entire process.

Analytical procedures.

Cell densities, expressed in milligrams of cell dry weight (CDW) per milliliter, were determined gravimetrically by using tared 0.2-μm-pore-size filters (Costar) (33). A densitometer (Molecular Dynamics) was used to quantify the protein content as described previously (11). β-Galactosidase activity was measured as previously described (19). One unit of β-galactosidase activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that hydrolyzes 1 nmol of o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside/min at 28°C. For PHA content determinations, lyophilized cells were analyzed according to a previously described method (12). A CP-Sil 5CB column (Chrompack) was used to identify methylated PHA monomers by gas chromatography.

Study of the stability of PHA granule-BioF proteins.

The stability of proteins was tested in 100 μl of a BioF-Lyt (FLyt) suspension containing 183 μg of PHA/ml at different temperatures, ionic strengths, and pHs. The following assay conditions were used: (i) incubation at −70, −20, 4, 37, 50, and 65°C in 15 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, for 2 h; (ii) incubation in 0, 5, 50, 100, 500, and 1,000 mM NaCl for 2 h at 4°C; and (iii) incubation at pHs 3, 4, 5, 6, 6.5 (15 mM sodium citrate buffer), 7, 7.5, 8, and 9 (15 mM Tris-HCl buffer) for 2 h at 4°C. After stability tests, granule samples were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C, and the proteins retained in the granules or released into the supernatant were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Every assay was performed in duplicate.

Computer analyses.

Protein sequence similarity searches were done by using the BLASTP and BLASTX programs available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST.

RESULTS

GAP-granule isolation by a simple centrifugation process.

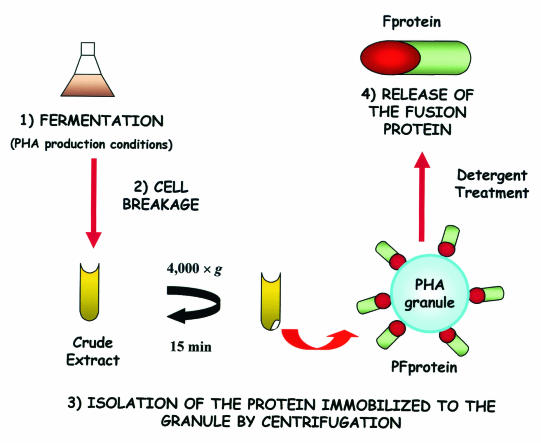

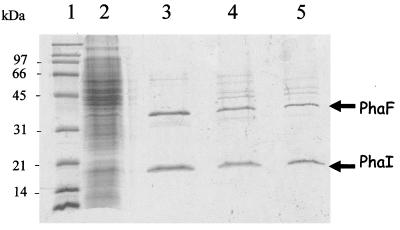

Taking into account the proposed modular structure of PhaF (22), we assumed that the N-terminal region of this protein could function as a polypeptide tag (BioF tag) to associate BioF fusion proteins (F proteins) with the mclPHA granules of P. putida GPo1, allowing us to develop an advantageous, inexpensive, and fast downstream process for isolating F proteins. With this in mind, we first accomplished a simplification of current protocols for purifying PHA granules (Fig. 1). In short, PHA biosynthesis was favored in Pseudomonas strains cultured in an octanoate-containing medium under nitrogen-limited conditions (10). Once the production of PHA granules was optimized, cells were processed, as indicated in Fig. 1, and the granules were isolated by alternative centrifugation methods which separated GAPs from the soluble and insoluble proteins (membrane and other cell structural proteins) of the crude extract. SDS-PAGE analysis of the granules isolated by such different centrifugation methods showed that the phasins, PhaF and PhaI, were in all cases the major proteins found in the granule fraction, and thus the simplest method tested, i.e., a single centrifugation step at 4,000 × g that concentrated the bioplastic as a white pellet, can be used for isolation purposes (Fig. 2).

FIG. 1.

Schematic final protocol for the immobilization (PFprotein) and purification (Fprotein) of BioF products.

FIG. 2.

Analysis of GAPs from P. putida GPo1. The image shows an SDS-PAGE (12.5%) analysis of GAPs isolated by different methods. Lane 3, ultracentrifugation through a sucrose gradient; lane 4, centrifugation (12,000 × g, 4°C) onto a discontinuous glycerol gradient; lane 5, simple centrifugation (4,000 × g, 30 min); lane 2, total crude extract of P. putida GPo1; lane 1, standard molecular size markers.

Immobilization of FLyt protein in PHA granules.

To demonstrate the feasibility of the BioF tag system, we first constructed an FLyt fusion protein. Taking advantage of extensive studies performed in our laboratory on the major pneumococcal autolysin, the amidase LytA (15), we fused the C-terminal domain of this protein, encoding a choline binding domain (ChBD), to the BioF tag, so the production of the protein could be monitored by using anti-ChBD antibodies (data not shown). A DNA fragment encoding the FLyt fusion protein was cloned into the shuttle plasmid pVLT35, generating a pNFA2 construction that is able to replicate in Pseudomonas strains (Fig. 3A). The strain P. putida GPG-Tc6, harboring an inactivated phaF gene, was used as a host for cloning and production purposes, since the inactivation of PhaF avoids the possible contamination of granules with the wild-type PhaF protein. It is worth noting that this strain still retains the ability to accumulate PhaF-free granules due to the presence of the second phasin, PhaI (22). To test the production of FLyt in P. putida GPG-Tc6(pNFA2), we used the experimental procedure described above for PHA granule production and isolation (Fig. 3B). The molecular mass (36 kDa) of FLyt associated with PHA granules was in agreement with its predicted theoretical mass (35,669 Da). Surprisingly, the FLyt protein was the major polypeptide present in the granules (Fig. 3C, lane 5), even displacing the PhaI phasin. This result not only confirmed our hypothesis that the N-terminal region of PhaF is responsible for granule binding, but also suggested that the F proteins can fulfill the physiological function ascribed to phasins for granule formation.

FIG. 3.

Outline of shuttle plasmid pNFA2 and immobilization and purification of FLyt product. (A) Construction of a shuttle plasmid expressing the flyt gene. Hatched arrows represent the DNA region coding for the ChBD. Black boxes represent the DNA region coding for the BioF tag. Abbreviations: Ev, EcoRV; H, HindIII; HII, HindII; Xb, XbaI; Plac, lac promoter of pUC18; Ptac, tac promoter of pVLT35. (B and C) SDS-PAGE (12.5%) analysis of FLyt production, immobilization, and purification process. Lane 1, soluble fraction of crude extract of P. putida GPG-Tc6; lane 2, complete (soluble and insoluble) crude extract of P. putida GPG-Tc6; lane 3, soluble fraction of crude extract of P. putida GPG-Tc6(pNFA2); lane 4, complete (soluble and insoluble) crude extract of P. putida GPG-Tc6(pNFA2); lane 5, GAPs of P. putida GPG-Tc6(pNFA2), with the FLyt protein immobilized; lanes 6 to 9, soluble granule fractions after treatment with detergents (lane 6, 0.15% Tween 20; lane 7, 0.15% sodium deoxycholate; lane 8, 0.15% Sarkosyl; lane 9, 0.15% Triton X-100). The molecular masses of the standard marker proteins are indicated. The position of the FLyt protein is indicated with arrows.

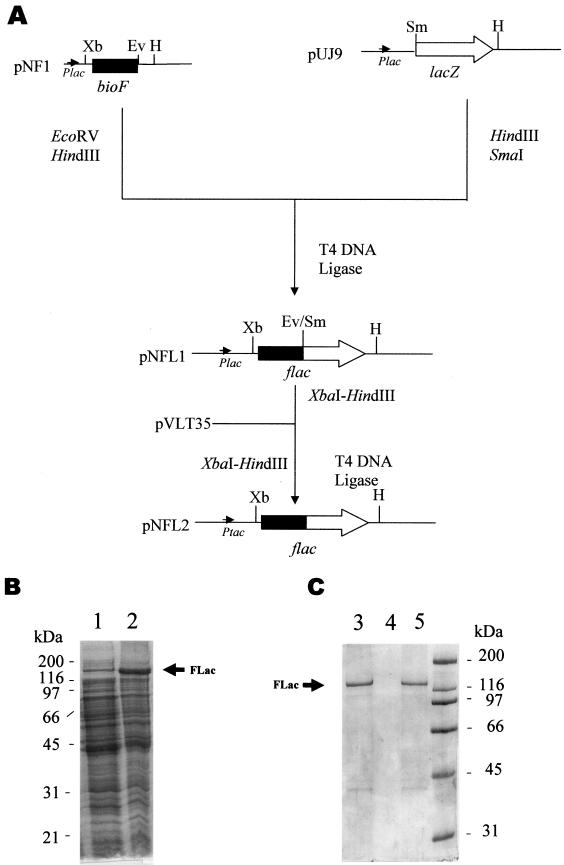

Immobilization of functional FLac enzyme in PHA granules.

Once the efficacy of the BioF tag was demonstrated, we tested the suitability of the method to immobilize F proteins with enzymatic activities. We cloned a DNA fragment encoding a BioF-LacZ protein (FLac) into the shuttle vector pVLT35, and the new recombinant plasmid, pNFL2, was introduced into P. putida GPG-Tc6 (Fig. 4A). SDS-PAGE analysis of the cell extract of P. putida GPG-Tc6(pNFL2) and of the isolated PHA granules showed a major protein of 130 kDa, which agrees with the predicted molecular mass of FLac (131,392 Da) (Fig. 4B and C). The β-galactosidase activity of the crude extract was 2.5 × 107 U/g of CDW, whereas that associated with the granules was 2.0 × 107 U/g of PHA, indicating that most of the enzymatic activity produced by the recombinant strain was immobilized in the granules. This result demonstrates that the BioF tag system also allows the immobilization and isolation of fully active enzymes.

FIG. 4.

Construction of shuttle plasmid pNFL2 and immobilization and purification of the enzyme FLac. (A) Construction of a shuttle plasmid that codes for the flac gene. White arrows represent the DNA region coding for the reporter lacZ. Black boxes represent the DNA region coding for the BioF tag. Abbreviations: Ev, EcoRV; H, HindIII; Sm, SmaI; Xb, XbaI; Plac, lac promoter of pUC18; Ptac, tac promoter of pVLT35. (B and C) SDS-PAGE (10%) analysis of FLac production, immobilization, and purification process. Lane 1, soluble fraction of crude extract of P. putida GPG-Tc6(pNFL2); lane 2, complete (soluble and insoluble) crude extract of P. putida GPG-Tc6(pNFL2); lane 3, GAPs of P. putida GPG-Tc6(pNFL2), with the FLac protein immobilized; lane 4, insoluble granule fraction after treatment with 0.15% Sarkosyl; lane 5, soluble granule fraction after treatment with 0.15% Sarkosyl. The position of the FLac protein is indicated with arrows. The molecular masses of the standard marker proteins are indicated.

Release of F proteins from PHA granules.

To facilitate the purification of soluble BioF proteins, we studied the possibility of releasing the F proteins from the granules under different physicochemical conditions (temperature, ionic strength, and pH). We observed that the FLyt protein remained attached to the granules under all ionic (up to 1 M NaCl) and pH (3 to 9) conditions tested, but about one-third of the FLyt protein could be released by freezing the granules at −20°C. We also analyzed the use of detergents as a method to release the F proteins from PHA granules (Table 2), and in this case, the most efficient detergents were Sarkosyl and Triton X-100 at 0.15% (wt/vol), which released 98 and 92% of the total immobilized protein, respectively (Table 2; Fig. 3C, lanes 8 and 9). Similar results were obtained when the granules carrying FLac were treated with 0.15% Sarkosyl (Fig. 4C, lane 5), yielding a 98% FLac recovery rate, with a specific activity of 220,000 U/mg of protein, similar to that of wild-type β-galactosidase (Table 3) (19). It is also worth noting that the FLyt protein released from the granules by Sarkosyl treatment was perfectly functional, since it could be further purified by affinity chromatography with choline-containing matrices, confirming that the ChBD of LytA had been appropriately folded (data not shown). Table 3 shows the detailed purification yields for FLyt and FLac proteins for the BioF protocol described in Fig. 1.

TABLE 2.

Release of FLyt protein from PHA granules by detergent treatment

| % Detergenta | % of FLyt releasedb

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tween 20 | Tween 80 | Brij 58 | Sodium deoxycholate | SDS | Sarkosyl | Triton X-100 | CHAPS | CTAB | |

| 15 × 10−4 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 9 | 9 | ND | ND |

| 15 × 10−3 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 19 | 84 | ND | ND |

| 15 × 10−2 | 13 | 34 | 29 | 13 | 69 | 98 | 92 | ND | ND |

| 15 × 10−1 | 13 | 41 | 32 | 16 | 88 | 98 | 100 | 71 | 88 |

| 15 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 82 | 100 |

The percent detergent (wt/vol) used in a FLyt-granule suspension in 15 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.

FLyt release is expressed as the percentage of the concentration of FLyt protein in the initial FLyt-granule suspension. ND, not determined. Each value is the average of values from three different experiments with a deviation of <3%.

TABLE 3.

FLyt and FLac purification yielda

| Protein | CDW (g · liter−1) | PHA (mg · liter−1) | Amt of protein immobilized (mg · mg of PHA−1) | U · mg of immobilized protein−1 | Amt of purified protein (mg · mg of PHA−1) | U · mg of pure protein−1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flyt | 0.1224 | 36.72 | 61.7 × 10−3 | 60.3 × 10−3 | ||

| Flac | 0.1848 | 48.60 | 70.0 × 10−3 | 2.8 × 105 | 68.6 × 10−3 | 2.2 × 105 |

Each value is the average of values from three different experiments with a deviation of <3%.

DISCUSSION

This work presents the first method for selectively immobilizing recombinant proteins on mclPHAs simultaneously with their biosynthesis in the bacterial cell. The immobilized protein can be isolated by a simple procedure, and a highly purified soluble protein can be released from the support by a mild detergent treatment (Fig. 1). The method is based on the construction of fusion proteins with the BioF tag, a polypeptide consisting of the N-terminal domain of the PhaF phasin, which is one of the major GAPs of the PHA granules of P. putida GPo1 (22).

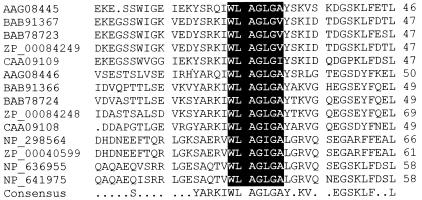

It has been postulated that phasins consist of a hydrophobic domain which associates with the surface of the PHA granules and a hydrophilic domain which is exposed to the cytoplasm of the cell (28). These GAPs are widespread among bacteria, sharing similar functions but differing in their primary structures. The phasin's amphiphilic layer stabilizes the PHA granules and prevents them from coalescing (21, 28). In the case of the phasin from Rhodococcus ruber, two short hydrophobic stretches close to the C terminus seem to be essential for granule binding (21). Our results demonstrate for the first time that the PhaF phasin of P. putida GPo1 contains a PHA binding domain that is located at the N-terminal region of the protein (BioF tag). The hydropathic plot of the BioF tag shows a clear hydrophobic region of seven residues (WLAGLGI) located at amino acid positions 26 to 32. Remarkably, this region is conserved in all of the PhaF-like annotated proteins (14 polypeptides) (Fig. 5), suggesting that this conserved motif plays a fundamental role in the association with and binding of the protein to the PHA granule. Although further research is needed to confirm this hypothesis, our results pave the way to understanding the function and evolution of PhaF phasins, which clearly appear to be modular bifunctional proteins. Moreover, they open the possibility of analyzing the complex PHA-phasin interactions in a more rational manner.

FIG. 5.

Multiple sequence alignment of PhaF-like proteins. A comparison of the amino acid sequences of the N-terminal domain of the PhaF protein of P. putida GPo1 (CAA09109) and those of other proteins in the databases that presented significant similarity, including the homologous proteins to PhaI, is shown. The numbers at the right indicate the positions of the residues in the complete amino acid sequence of the protein. A consensus sequence was deduced for positions at which the residues were identical in at least 7 of the 14 compared sequences. Black shading indicates the hydrophobic region that is conserved in all PhaF-like proteins. The accession numbers correspond to PhaF-like proteins from the following microorganisms: AAG08445, Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA01; BAB91367, Pseudomonas sp. strain 61-3; BAB78723, Pseudomonas chlororaphis; ZP_00084249, Pseudomonas fluorescens; CAA09109, P. putida GPo1; AAG08446, P. aeruginosa PA01; BAB91366, Pseudomonas sp. strain 61-3; BAB78724, P. chlororaphis; ZP_00084248, P. fluorescens; CAA09108, P. putida GPo1; NP_298564, Xylella fastidiosa 9A5C; ZP_00040599, X. fastidiosa ANN-1; NP_636955, Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris ATCC 33913; NP_641975, X. campestris pv. citri 306.

One of the main requirements for a useful tag is that its fusion does not alter the properties of the attached protein. In this respect, we have demonstrated that the BioF tag does not affect the folding of binding domains, such as the ChBD, or the activities of enzymes with a complex quaternary structure, like the FLac galactosidase. Therefore, BioF appears to be very useful for isolating different kinds of proteins independent of their tertiary or quaternary structures. Our results suggest that the hydrophobic domain of BioF is located far enough from the linker region that the attached proteins are placed far away from the lipid layer of the granule, avoiding hydrophobic interactions that could be deleterious for some proteins. In addition to the great advantage of recovering active proteins by a simple centrifugation step, the BioF system offers the possibility of releasing the proteins by a mild detergent treatment of the isolated PHA granules (Table 2), increasing its versatility by facilitating the utilization of soluble proteins. Remarkably, the BioF tag does not alter the solubility of the fused proteins, since we observed that the FLyt protein purified by affinity chromatography with choline supports remained perfectly soluble.

We had previously observed that the lack of PhaF protein in the P. putida GPG-Tc6 strain, the host of choice for F-protein production, did not alter the number and size of granules produced when the culture was grown under nitrogen-limited conditions. In this case, a granule extract analysis showed PhaI to be the major protein component of such granules (22). However, in the recombinant strains described in this work, the FLac and FLyt proteins encoded by the pVLT35-derived plasmids were the most prominent bands that could be seen in the corresponding purified granule fractions (Fig. 3 and 4). These results suggest that the main factor which determines the preferred granule-covering protein is the amount of the specific phasin inside the cell, following a classical competitive binding mechanism. Thus, since the level of the recombinant BioF-like-phasin is much higher than that of the PhaI protein, it is preferred to cover the whole surface of the granule, displacing the PhaI protein. This hypothesis is in agreement with the calculated amounts of FLyt and FLac when they are associated with the granule (6.1 and 7.0% of the total PHA mass, respectively) (Table 3). These percentages are considerably higher than that described for other PHA granules, such as those of Bacillus megaterium, in which GAPs represent close to 2% of the total mass of a standard granule (8).

In addition, the use of the BioF tag provides some advantages over other known methods of immobilization and purification of proteins. In this competitive field, there are several parameters which may be considered to compare the usefulness of the methods published so far. In this sense, a critical point for selecting a specific tag could be the possibility to scale the process to an industrial level and to purify the fused protein of interest at a low cost. The use of BioF as an affinity tag to bind to the surfaces of granules, the purification of such granules through a simple centrifugation step, and the final release of the fusion protein by a detergent treatment may constitute a substantial improvement over the methods that are available in the market. It is worth mentioning that the procedures for producing PHA by large-scale fermentation are very well established (4). Moreover, several methods for producing mclPHA in recombinant E. coli have recently been described (20, 23). These approaches are currently in progress in our lab in order to expand the benefits of this tool in the field of biotechnology. Another noticeable advantage of the BioF system is the possibility of immobilizing any fused protein in a biodegradable support, which might be especially useful for spreading fused peptides or proteins on fields for agricultural and environmental purposes.

In summary, the BioF tag system described here not only provides a novel tool for investigating the evolution and function of phasins and the formation of PHA granules, but also offers an innovative alternative method for purifying, immobilizing, and spreading fusion proteins.

Acknowledgments

We thank E. García, E. Díaz, and R. López for helpful comments. We also acknowledge A. Cebolla (BioMedal) for his continuous encouragement. We are indebted to N. Sierro for his support with the PHA assay.

C. Moldes was a recipient of a fellowship from the Fundación Ramón Areces. This work was supported by a grant from the Fundación Ramón Areces and by a grant from the European Union (QLK3-CT-2002-01969).

REFERENCES

- 1.de Lorenzo, V., L. Eltis, B. Kessler, and K. Timmis. 1993. Analysis of Pseudomonas gene products using lacIq/Ptrp-lac plasmids and transposons that confer conditional phenotypes. Gene 123:17-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Lorenzo, V., M. Herrero, U. Jakubzik, and K. N. Timmis. 1990. Mini-Tn5 transposon derivatives for insertion mutagenesis, promoter probing, and chromosomal insertion of cloned DNA in gram-negative eubacteria. J. Bacteriol. 172:6568-6572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dower, W. J., J. F. Miller, and C. W. Ragsdale. 1988. High efficiency transformation of Escherichia coli by high voltage electroporation. Nucleic Acids Res. 16:6127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Durner, R., M. Zinn, B. Witholt, and T. Egli. 2001. Accumulation of poly[(R)-3-hydroxyalkanoates] in Pseudomonas oleovorans during growth in batch and chemostat culture with different carbon sources. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 72:278-288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Einhauer, A., and A. Jungbauer. 2001. The FLAG peptide, a versatile fusion tag for the purification of recombinant proteins. J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods 49:455-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuller, R. C., J. P. O'Donnel, J. Saulnier, T. E. Redlinger, J. Foster, and J. W. Lenz. 1992. The supramolecular architecture of the polyhydroxyalkanoate inclusions in Pseudomonas oleovorans. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 103:279-288. [Google Scholar]

- 7.García, P., J. L. García, E. García, and R. López. 1986. Nucleotide sequence and expression of the pneumococcal autolysin gene from its own promoter in Escherichia coli. Gene 43:265-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Griebel, R., Z. Smith, and J. M. Merrick. 1968. Metabolism of poly-beta-hydroxybutyrate. I. Purification, composition, and properties of native poly-beta-hydroxybutyrate granules from Bacillus megaterium. Biochemistry 7:3676-3681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herrero, M., V. de Lorenzo, and K. N. Timmis. 1990. Transposon vector containing non-antibiotic selection markers for cloning and stable chromosomal insertion of foreign DNA in gram-negative bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 172:6557-6567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huisman, G. W., E. Wonink, G. J. M. de Koning, H. Preusting, and B. Witholt. 1992. Synthesis of poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates) by mutant and recombinant Pseudomonas strains. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 38:1-5. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kraak, M. N., T. H. M. Smits, B. Kessler, and B. Witholt. 1997. Polymerase C1 levels and poly(R-3-hydroxyalkanoate) synthesis in wild-type and recombinant Pseudomonas strains. J. Bacteriol. 179:4985-4991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lageveen, R. G., G. W. Huisman, H. Preusting, P. Ketelaar, G. Eggink, and B. Witholt. 1988. Formation of polyesters by Pseudomonas oleovorans: effect of substrates on formation and composition of poly-(R)-3-hydroxyalkanoates and poly-(R)-3-hydroxyalkenoates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 54:2924-2932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.La Vallie, E. R., and J. M. McCoy. 1995. Gene fusion expression systems in Escherichia coli. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 6:501-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liebergesell, M., B. Schmidt, and A. Steinbüchel. 1992. Isolation and identification of granule-associated proteins relevant for poly(3-hydroxyalkanoic acid) biosynthesis in Chromatium vinosum D. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 99:227-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.López, R., E. García, P. García, and J. L. García. 1997. The pneumococcal cell wall degrading enzymes: a modular design to create new lysins? Microb. Drug Resist. 3:199-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Madison, L. L., and G. W. Huisman. 1999. Metabolic engineering of poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates): from DNA to plastic. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63:21-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCool, G. J., and M. C. Cannon. 1999. Polyhydroxyalkanoate inclusion body-associated proteins and coding region in Bacillus megaterium. J. Bacteriol. 181:585-592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merrick, J. M., and M. Doudoroff. 1964. Depolymerization of poly-β-hydroxybutyrate by an intracellular enzyme system. J. Bacteriol. 88:60-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 20.Park, S. J., and S. Y. Lee 2003. Identification and characterization of a new enoyl coenzyme A hydratase involved in biosynthesis of medium-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoates in recombinant Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 185:5391-5397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pieper-Fürst, U., M. H. Madkour, F. Mayer, and A. Steinbüchel. 1995. Identification of the region of a 14-kilodalton protein of Rhodococcus ruber that is responsible for the binding of this phasin to the polyhydroxyalkanoic acid granules. J. Bacteriol. 177:2513-2523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prieto, M. A., B. Buehler, K. Jung, B. Witholt, and B. Kessler. 1999. PhaF, a polyhydroxyalkanoate granule-associated protein of Pseudomonas oleovorans GPo1 involved in the regulatory expression system for pha genes. J. Bacteriol. 181:858-868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prieto, M. A., M. B. Kellerhals, G. B. Bozzato, D. Radnovic, B. Witholt, and B. Kessler. 1999. Engineering of stable recombinant bacteria for production of chiral medium-chain-length poly-3-hydroxyalkanoates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:3265-3271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 25.Sassenfeld, H. M. 1990. Engineering proteins for purification. Trends Biotechnol. 8:88-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schembri, M. A., A. A. Woods, R. C. Bayly, and J. K. Davies. 1995. Identification of a 13-kDa protein associated with the polyhydroxyalkanoic acid granules from Acinetobacter spp. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 133:277-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steinbüchel, A., and S. Hein. 2001. Biochemical and molecular basis of microbial synthesis of polyhydroxyalkanoates in microorganisms. Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol. 71:81-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steinbüchel, A., K. Aerts, W. Babel, C. Föllner, M. Liebergesell, M. H. Madkour, F. Mayer, U. Pieper-Fürst, A. Pries, H. E. Valentin, and R. Wieczorek. 1995. Considerations of the structure and biochemistry of bacterial polyhydroxyalkanoic acid inclusions. Can. J. Microbiol. 41:94-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stuart, E. S., A. Tehrani, H. E. Valentin, D. Dennis, R. W. Lenz, and R. C. Fuller. 1998. Protein organization on the PHA inclusion cytoplasmic boundary. J. Biotechnol. 64:137-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uhlén, M., G. Forsberg, T. Moks, M. Hartmanis, and B. Nilsson. 1992. Fusion proteins in biotechnology. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 3:363-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wieczorek, R., A. Steinbüchel, and B. Schmidt. 1996. Occurrence of polyhydroxyalkanoic acid granule-associated proteins related to the Alcaligenes eutrophus H16 GA24 protein in other bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 135:23-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Witholt, B., G. Eggink, and G. W. Huisman. September 1994. U.S. patent 5,344,769.

- 33.Wubbolts, M. G., O. Favre-Bulle, and B. Witholt. 1996. Biosynthesis of synthons in two-liquid-phase media. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 52:301-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]