Abstract

Objective

Murine models have proven instrumental in studying various aspects of abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) ranging from identification of underlying pathophysiology to the development of novel therapeutic strategies. In the current study, we describe a new model in which an elastase-treated donor aorta is transplanted to a recipient mouse and allowed to progress to aneurysm. We hypothesized that by transplanting an elastase-treated abdominal aorta of one genotype to a recipient mouse of a different genotype, one can differentiate pathophysiological factors that are intrinsic to the aortic wall from those stemming from circulation and other organs.

Methods

Elastase-treated aorta was transplanted to the infrarenal abdominal aorta of recipient mice by end-to-side microsurgical anastomosis. Heat inactivated elastase-treated aorta was used as a control. Syngeneic transplants were performed using 12-week-old C57BL/6 littermates. Transplant grafts were harvested from recipient mice on day 7 or 14 post-surgery. The aneurysm outcome was measured by aortic expansion, elastin degradation, pro-inflammatory cytokine expression, and inflammatory cell infiltration and compared to that produced with the established, conventional elastase-infusion model.

Results

The surgical technique success rate was 75.6%, and the 14-day survival rate was 51.1%. By Day 14 post-surgery all of the elastase-treated transplanted abdominal aorta had dilated and progressed to AAAs defined as 100% or more increase in the maximal external diameter compared to that measured before elastase perfusion, while none of the transplanted aortas pre-treated with inactive elastase became aneurysmal (percentage increase in maximum aortic diameter: 159.36±23.27% (transplanted elastase) vs. 41.46±9.34% (transplanted inactive elastase). Aneurysm parameters, including elastin degradation, infiltration of macrophages and T lymphocytes were found to be identical to those observed in the conventional elastase model. Quantitative PCR analysis revealed similarly increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (relative changes of mRNA in the conventional elastase model versus transplant model: Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha, TNF-α 1.71±0.27 vs. 2.93±0.86; Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1, MCP-1 2.36±0.58 vs. 2.87±0.51; Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 5, CCL5 3.37±0.92 vs. 3.46±0.83; and Interferon gamma, IFN-γ 3.09±0.83 vs. 5.30±1.69). Utilizing Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) transgenic mice as either donors or recipients, we demonstrated a small quantity of mononuclear leukocytes in the transplant grafts bared the genotype of the donors.

Conclusions

Transplanted elastase-treated abdominal aorta could develop to aneurysm in recipient mice. This AAA transplant model can be used to examine if and how the microenvironment of a transplanted aneurysmal aorta can be altered by the contributions of the ‘global’ environment of the recipient.

INTRODUCTION

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is a common disease with a high prevalence of death.1, 2 While significant advances have been made in aneurysm imaging as well as in surgical intervention methods, effective pharmacological treatments have remained elusive. Aggressive management of hypertension and hyperlipidemia is recommended in patients with AAA, however, therapies for these conditions have no proven effects on aneurysm growth and rupture.3 Elective aneurysm repair is generally not recommended for AAAs with the diameter less than 5.5 cm, based on results of two large randomized clinical trials.4, 5 Although epidemiologic and pathological studies have yielded important clues regarding the pathogenesis of abdominal aortic aneurysms, the use of animal models, particularly mouse models, has been invaluable in revealing cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying AAA pathogenesis and also in identifying potential therapeutic targets.6, 7 Despite the anatomical and physiologic differences between mouse and human and the inherent technical challenges for small animal surgery, mouse model work serves as an important stepping stone from laboratory bench to bedside. The various murine AAA models could be roughly divided into two categories: genetic approaches and chemical approaches.6, 8–12

The chemical approaches include intraluminal infusion of elastase, periaortic incubation of calcium chloride, and subcutaneous infusion of Angiotensin II (Ang II), or modifications of these methods.6, 13 These models, to various degrees, recapitulate many important aspects of human aneurysm including medial degeneration, transmural inflammation, and matrix remodeling. By using these models in various knockout and transgenic mice, investigators can examine the role of specific genes in the pathogenesis of AAA. However, tissue-specific knockout or transgenic mice are not always available.

In order to determine in which cell types a particular gene exerts it pro- or anti-aneurysmal effect, bone marrow cell (BMC) transplantation is frequently employed. This approach has been used successfully to identify inflammatory cells as an important source of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP9).14 However, certain transgenic strains may suffer high mortality following irradiation and BMC transplantation. Johnston et al reported only 53% and 27% survival rates in mice deficient in interleukin-1 receptor (IL-1R) that were subjected to lethal irradiation and transplantation with BMCs from the wildtype and IL-1R knockout mice, respectively.15. In an effort to develop a reliable alternative approach, we adapted an orthopic allograft transplantation model in which an elastase treated artery is grafted to an untreated recipient mouse. We tested our hypothesis that by transplanting an elastase-treated abdominal aorta of one genotype to a recipient mouse of a different genotype, one can differentiate pathophysiological factors that are intrinsic to the aortic wall from those stemming from circulation and other organs. Using GFP transgenic mice, we showed that this is a feasible approach for studying how an aneurysm from one genotype will progress in a different recipient genotype.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

C57BL/6 and GFP+ C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories. Male mice, 12-week-old weighing 25–30g were used. Surgical procedures were carried out under an operative microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY), with 10× to 40× magnifications (Supplemental video). The microsurgical instruments used in this model are listed in Supplemental Table 1. All animal procedures in this study were conducted in accordance with experimental protocols that were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Wisconsin, Madison (Protocol M02284).

Donor Operation

Donor mice were subjected to the elastase-infusion procedure as previously described.16, 17 Mice were anesthetized with inhaled isoflurane 1.5–2.0 L/min. The abdomen was shaved and scrubbed with betadine. The mouse was placed supine on the operative field. After a long midline abdominal incision was made, the abdominal aorta was isolated from the level of the left renal vein to the bifurcation, and the diameter of the largest portion was measured and recorded. All aortic branches between the renal arteries and bifurcation were ligated with 9-0 suture. Temporary 6-0 silk ligatures were placed around the proximal and distal portions of the aorta. An aortostomy was created with a 30G needle. Heat-tapered polyethylene tubing (IN-10, ROBOZ) was introduced through the aortostomy and secured with a silk ligature. Using a saline bag hung at the height of 136 cm to calibrate 100 mmHg, the infrarenal aorta was temporarily perfused with a saline solution containing the 0.45 U/mL type I porcine pancreatic elastase saline solution for 5 min (E-1250, Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Control mice were similarly infused with the elastase solution that had been heated at 100°C for 15 min (heat-inactivated elastase). Measurements of external aortic diameters indicated similar initial expansion in both groups (inactive elastase treated 31±3.5% vs. elastase treated 36±2.8%), which is consistent with what was reported in the literature18. Following the removal of perfusion catheter, the segment of elastase-treated aorta was transected between the upper ligation and aortostomy, and stored in saline containing heparin 100U/mL at 4°C until transplantation.

Recipient Operation

After anesthesia and midline abdominal incision, the intestines were retracted to right side to expose the retro-peritoneum. The infrarenal aorta was dissected from the vena cava between the renal arteries and the iliac bifurcation. The branches of the abdominal aorta were exposed and ligated with 9-0 sutures. The donor aorta was end-to-side anastomosed to the recipient aorta with interrupted suture (11-0) (Figure 1). After the distal anastomosis was completed, the distal ligature was removed, followed by the removal of the proximal ligature is removed. The abdominal incision was closed in two layers with 6-0 nylon sutures. 1% Lidocaime drops were placed on the wound. The mouse was kept on a warming pad until fully recovered from anesthesia. Warm saline (0.5 ml) was subcutaneously injected to maintain fluid homeostasis. Following operation, mice were monitored each hour for the first 4 hours and then once daily. No antibiotics or immunosuppression were used. Technical success was defined as survival without paralysis after recovery from the anesthesia. Overall survival was defined as survival without paralysis until the mice were sacrificed after 7 or 14 days.

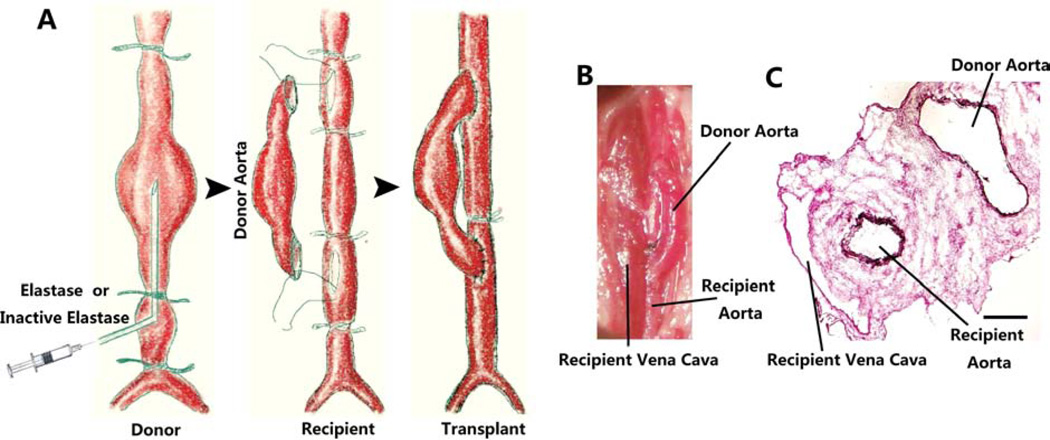

Figure 1.

A. Schematic representation of aorta transplant model of murine AAA induced by elastase. Prior to transplantation, donor’s abdominal aorta was perfused with porcine elastase (0.45U/mL, 10 min) under a pressure of 100mmHg. Donor’s aorta was then harvested and anastomosed to the recipient abdominal aorta in an end-to-side fashion. B. Representative photo of elastase-treated allograft immediately following the transplant procedure. C. Van Giesson stain shows the aneurysm formation of the transplanted abdominal aorta and the medial elastin degradation of aorta from the donor 14 days after surgery. Scale bar =200µm.

Histology

Mice were euthanized and tissues were perfused with PBS at physiologic perfusion pressure. The maximum external diameter of the infrarenal aorta was measured using a digital caliper (VWR Scientific, Radnor, Pa) before treatment and at the time of tissue harvest. The presence of AAA was defined as an increase in aortic diameter that was 100% greater than the size of vessel before perfusion18. Harvested tissue was imbedded in optimal cutting temperature compound (Sakura Tissue Tek). Cross sections were cut at 6-µm thick using a Microtome (Leica CM3050S Cryostat). Samples were stained with H&E and van Gieson (Richard-Allan Scientific, Kalamazoo, Mich) according to protocols provided by manufacturer. For immunohistochemistry, arterial sections were permeabilized with 0.1% TritonX for 10 minutes at room temperature. Nonspecific sites were blocked using 5% bovine serum albumin and 3% normal goat serum in Tris-buffered saline and Tween 20 for 1hr at room temperature. Antibodies were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA; CD3, 1:300, smooth muscle actin 1:1000; Caspase-3, 1:200; GFP 1:500), AbD serotec (CD68, 1:300). Quantification of stains was performed using Image J Software as provided by the National Institutes of Health as previously described.16, 17 Data quantification was performed using at least 8 sections per artery.

RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from abdominal aortic aneurysm tissue by using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, CA) according to manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA was synthesized using High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, CA) on a Veriti 96-well Thermal Cycler (Applied Biosystems, CA). Primers were purchased from QIAGEN (MCP-1: QT00167832, CCL5: QT01747165, TNF-α: QT00104006, IFN-γ: QT01038821, GAPDH: QT01658692) and amplification was detected using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, CA). Real-time PCR was carried out using a 7500 Fast Real-time PCR System Machine (Applied Biosystems, CA). RQ value, where RQ= (EtargetΔCPtarget (control-sample))/(EreferenceΔCPref (control-sample)), the reference gene was GAPDH, and CP is defined as a ‘crossing point’, was used to compare expression of target cytokines.

Statistical analysis

Values were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Experiments were repeated at least three times unless stated otherwise. Differences between 2 groups were analyzed by Student’s t test after the demonstration of homogeneity of variance with an F test. One-way ANOVA analysis was followed by Bonferroni’s test to adjust for multiple comparisons. Values of P<.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Procedure summary

The donor aorta, treated with elastase or heat-inactivated elastase, was anastomosed to recipient infrarenal abdominal aorta in an end-to-side fashion (Figure 1). Anastomoses were completed in about 40 minutes (range, 28 to 60 minutes) by interrupted suture. The first 45 elastase-treated orthotopic abdominal aortic transplants were divided into three groups in sequence: 1–15, 16–30, 31–45. Kaplan-Meier survival curve shows the survival rate of each group (Suppl. Fig. 1A). Table 1 summarizes the perioperative mortality and causes of death for the procedure. The technique success rate was 75.6%, and the overall survival rate was 51.1%. The intraoperative mortality was 24.4% mainly due to exsanguination. Postoperative complications of this procedure included thrombosis of the aorta (5 cases out of 45), bleeding (2 cases out of 45), aneurysm rupture (1 cases out of 45), and hypovolemic shock (1 cases out of 45). (Suppl. Fig. 1B).

Table 1.

14-day Outcomes of the elastase-treated abdominal aorta transplanted murine in the early 45 mice

| Procedure number |

Technique Success rate (%) |

Survival rate (%) |

AAA Incidence (%) |

Mortality and Morbidity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intraoperative Death |

Thrombosis | Bleeding | Rupture | Hypovolemic Shock |

Unknown Death |

||||

| 1–15 | 66.7 (10/15) | 26.6 (4/15) | 75 (3/4) | 5 | 2 | 2a | - | 1 | 1 |

| 16–30 | 73.3 (11/15) | 53.3 (8/15) | 100(8/8) | 4 | 2 | - | 1b | - | - |

| 30–45 | 86.7 (13/15) | 73.3 (11/15) | 100(11/11) | 2 | 1 | - | 1 | ||

| overall | 75.6 (34/45) | 51.1.(23/45) | 95.7 (22/23) | 11 | 5 | 2- | 1 | 1- | 2 |

Died postoperatively after heparin subcutaneous injection 10U/g

Abdominal aortic aneurysm rupture

Macroscopic characterization

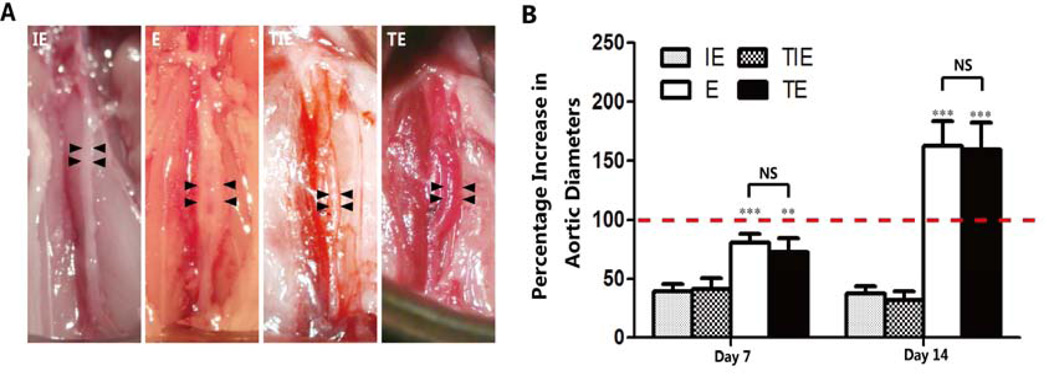

All except one of the elastase-treated transplanted abdominal aorta (22/23, 95.7%) dilated and progressed to aneurysm by day 14 post transplantation. The percentage increase in maximum diameter measured 14 days after transplantation was significantly higher in transplanted elastase treated aortas (159.36±23.27%) than transplanted inactive elastase treated aortas (41.46±9.34%). Similarly, measurements taken 7 days after surgery displayed significantly greater expansion in transplanted elastase treated aortas (72.41±11.88%) as compared to transplanted inactive elastase treated aortas (32.22±7.43%). The aortic expansion noted in our transplant model is similar to that of the conventional elastase model (72.41±11.88% vs.80.75±7.79% in transplanted and conventional elastase treated arteries at day 7, P>.05; and 159.36±23.27% vs. 162.55±21.44% at day 14, P>.05) (Figure 2). These results suggest the transplant procedure itself has little impact on aneurysm development.

Figure 2.

Aortic expansion in the transplant model of elastase-induced AAA was similar to that of the conventional elastase model. A, Representative pictures show the aortic expansion 14 days post-surgery from the (moving from left to right) inactive elastase-treated group (IE), elastase-treated group(E), inactive elastase-treated transplant group, and elastase-treated transplant group. Scale bars = 2 mm. B. The percent increase of maximum AAA diameters of each group, n=5 in each 7-day group, n=6 in each 14-day group. **P<.01; ***P<.001 (E vs. IE, Transplanted elastase treated aortas vs. Transplanted inactive elastase treated aortas). NS, Not Significant.

Histopathological characterization

Allografts harvested 7 or 14 days after surgery were used for histological examination. Measurement of aortic cross sections confirmed luminal dilation regardless of transplantation in elastase-treated tissues. The aortic walls of transplanted elastase treated and conventional elastase (E) groups consistently displayed thinner medial layers, but expanded adventitia as compared to aortas treated with inactivated elastase (the transplanted inactive elastase treated and conventional inactivated elastase (IE) groups) (Suppl. Fig. 2). The elastase-induced degeneration and disruption of elastic lamina, as well as the paucity of medial SMCs, was similar between the transplanted elastase treated and E groups (Suppl. Fig. 2). And there was no obvious intimal proliferation in either abdominal aortic allograft group (Suppl. Fig. 2).

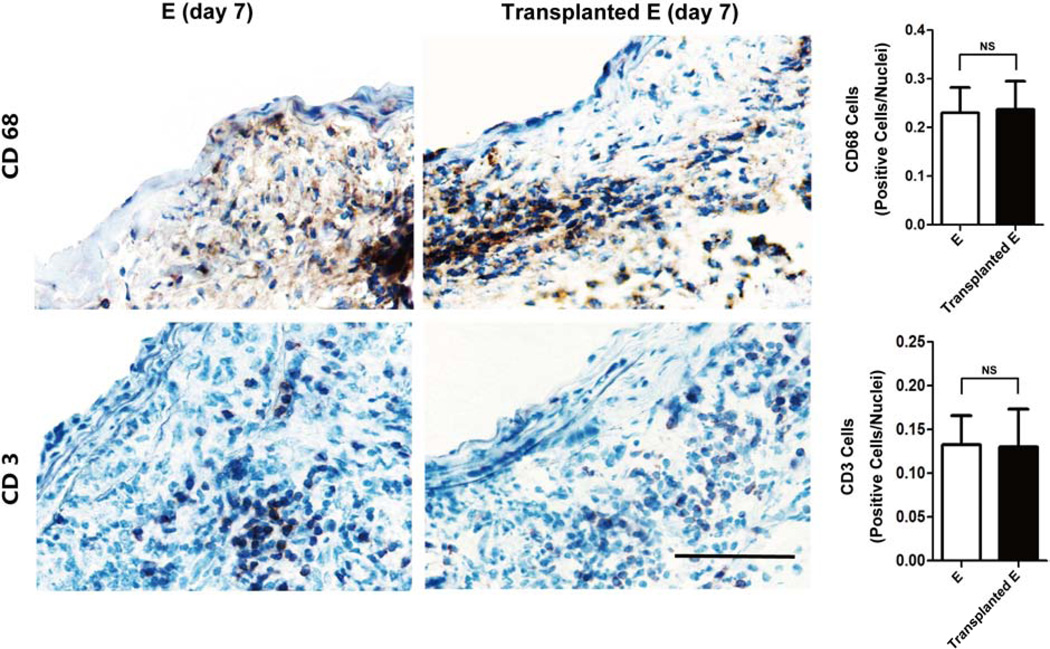

We examined vascular inflammation by immunohistochemical analysis using antibodies against CD3 (T lymphocyte marker) and CD68 (macrophage marker). Similar to what has been reported in the conventional elastase model, abundant T lymphocytes and macrophage populations were detected in adventitia and media of elastase-treated transplant grafts (Figure 3). Collectively, our data indicated that the orthotopic abdominal aortic transplant model produced similar aneurysmal dilatation and histological characteristics as have been observed in the conventional elastase model.

Figure 3. Macrophage (CD68 positive cells) and lymphocyte (CD3 positive cells) infiltration in elastase-treated abdominal aortas (E) and transplanted elastase-treated abdominal aortas (Transplanted E) 7 days post-surgery.

Scale bar=50µm. Quantification of macrophage and lymphocyte infiltration in aneurysm tissues as identified by CD68 and CD3 stains, respectively, expressed as CD68 or CD3 positive cells/nuclei. NS, Not Significant, n=5.

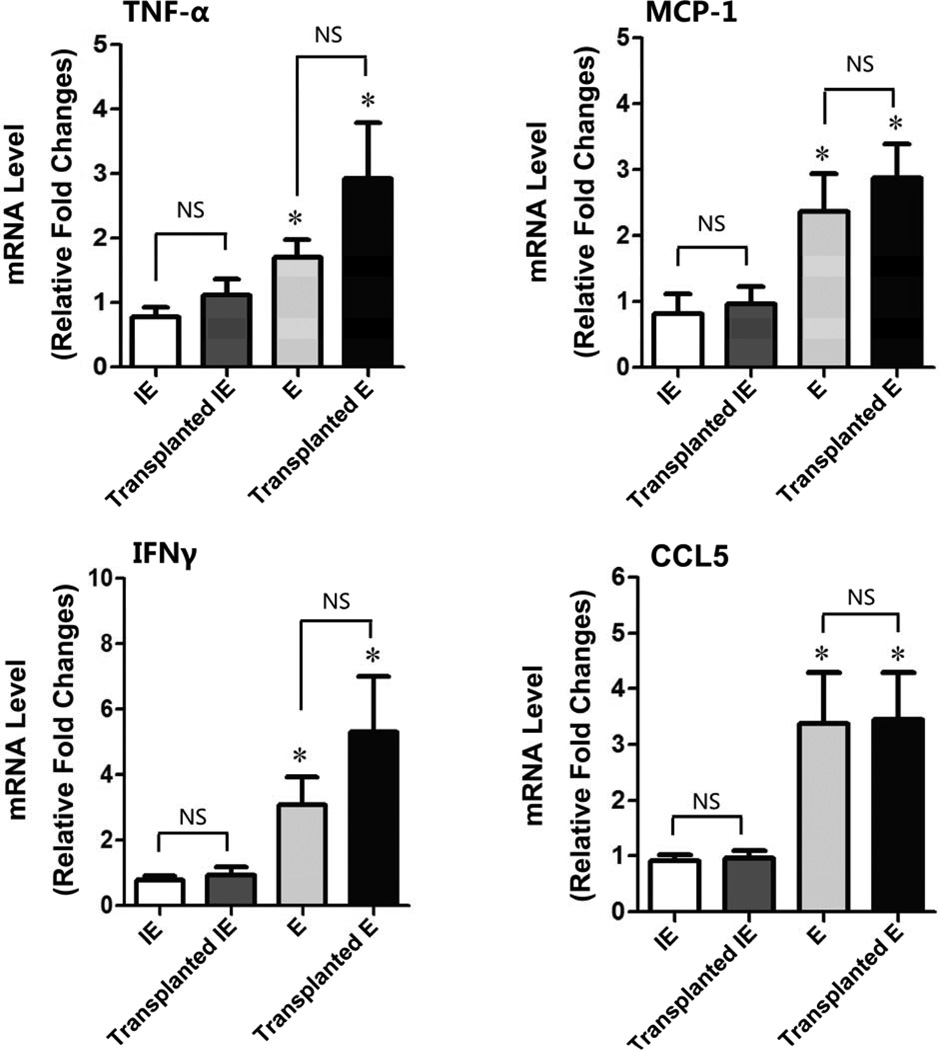

Cytokine expression

We further compared the inflammatory response in the elastase-treated aorta grafts with that measured in the conventional elastase model by measuring local production of proinflammatory cytokines. Two weeks after transplantation, mRNA expression of TNF-α, MCP-1, CCL5, and IFN-γ was significantly upregulated in the elastase-treated transplanted aorta compared with inactive elastase-treated transplanted aorta (P<.05) (Figure 4). The upregulation of those proinflammatory cytokines was similar to that observed in the conventional elastase model.

Figure 4. Transplanted elastase-induced abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) had a similar inflammatory phenotype as the conventional elastase-treated AAA.

14 days post-surgery, the AAA tissues were harvested from different experimental groups: inactive elastase-treated (IE, n=8), transplanted inactive elastase-treated (Transplanted IE, n=6), elastase-treated (E, n=6), and transplanted elastase-treated (Transplanted E, n=7). Relative fold changes of mRNA levels were determined by real-time PCR. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. *P<.05 (E vs. IE, Transplanted E vs. Transplanted IE); NS, Not Significant.

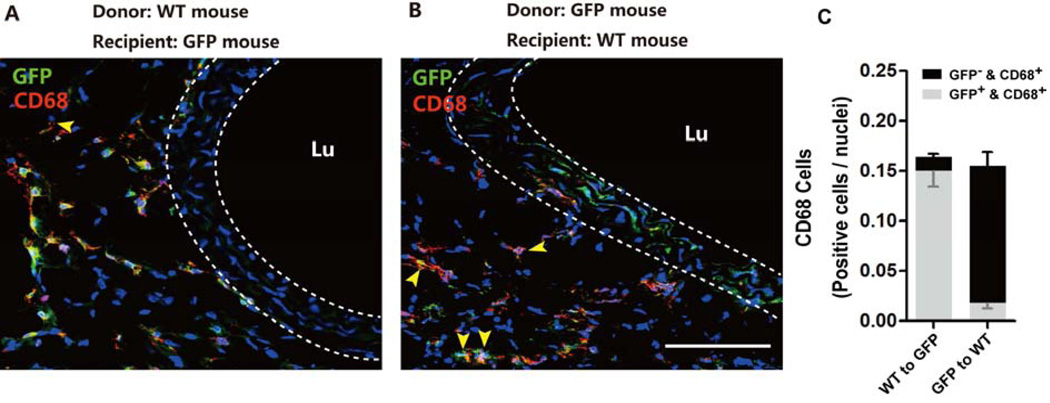

Origins of the inflammatory cells

In order to demonstrate that our newly developed transplant model can be carried out between mice of different genotypes, we transplanted elastase-treated abdominal arteries from wide type mice to GFP mice, and vice versa. Both sets of transplant cohorts survived and aortic grafts developed aneurysm. As shown in Figure 5A, when wildtype aortas were transplanted to GFP recipients, the majority of medial cells in the grafts were negative of GFP. The converse was observed in the GFP-to-wild type transplant cohort (Figure 5B). As expected, the majority of CD68+ macrophages carried the genotype of the recipients. However, in both transplant cohorts, we did identify a small quantity of CD68+ cells that bared the genotype of the donor, demonstrating that some macrophages arose from a residential population rather than from circulation (Figure 5C)

Figure 5. Both recipient- and donor-derived macrophages are present in elastase-treated transplant grafts.

Elastase-treated abdominal aorta segments were allografted from C57B6 mice into GFP+ C57B6 mice (A), and vice versa (B). Representative confocal immunofluorescence images for macrophage marker CD68 (red) and GFP (green) in allografts 7 days after transplantation. Nuclei stained with DAPI (blue). The yellow arrowheads indicate CD68 and GFP double positive cells. Lumen denoted as Lu. Scale bar=100µm. (C) Quantification of GFP+/CD68+ or GFP−/CD68+ cells in transplanted elastase-treated aneurysms, n=5.

DISCUSSION

Orthotopic transplantation of abdominal aorta, thoracic aortic arch, and carotid artery has been established decades ago,19–26 but these procedures were designed to study chronic rejection, allograft vasculopathy, or atherosclerosis. Orthotropic abdominal aorta transplant has not been reported in studies of aneurysm. Thus, we developed a murine abdominal aortic aneurysm model by orthotopic allograft transplantation of elastase-treated abdominal aorta. Data from our macroscopic and microscopic analyses indicate that this transplant AAA model displayed pathological characteristics analogous to that of the established mouse elastase-perfusion AAA model. The principal advantages of this transplant AAA model include 1) it generates a rapid forming aneurysm through a well-established chemical induction; 2) it permits exploitation of the rich genetic resources of murine species; 3) it allows transplantation between donors and recipients of different genotypes; and 4) it enables identification of cell origin without subjecting recipient mice to irradiation. Different from the thoracic aortic arch transplantation,19, 27 anastomosis of the orthotopic abdominal aorta transplantation is more challenging due to the smaller diameter of the mouse abdominal aorta. Even under adequate magnification, the surgery requires highly skilled maneuvers. However, with a skilled operator, high experimental success rate could be achieved. In our current study, the overall survival rate was higher than 70%. Two major causes of death were bleeding during the operation and post-operative aortic thrombosis, which could result in hind limb paralysis and followed by rapid deterioration to death within 72 hours.

In our study, all elastase-treated transplanted abdominal aorta (6 out of 6) became dilated and progressed to aneurysm on day 14 post-surgery. We attribute the cause of aneurysm of aorta grafts to the elastase infusion because none of the aorta grafts that were pretreated with heat-inactivated elastase developed aneurysm. Macroscopically and microscopically, the transplanted grafts exhibited morphological features including progressive aortic dilatation, disruption of elastic fibers, and vascular inflammation that resembled those of murine elastase-perfusion AAA model. In fact, we did not observe a statistically significant difference between our transplant model and the conventional elastase model in any of the parameters measured, suggesting the transplant procedure alone has no significant impact on aneurysm development.

We observed an abundant and diffuse infiltration of lymphocytes and mononuclear cells in the intima, media, and adventitial layers. In the media, elastic fibers were disrupted and smooth muscle cells presented focal degeneration. A considerable amount of monocyte and lymphocyte infiltration was observed in the adventitia. The absence of intimal proliferation and thickening in these abdominal aortic allografts is different from carotid allograft transplantation and the murine thoracic aortic transplant model of chronic rejection22, but similar to those of isograft transplantation28–30. We speculate the pro-inflammatory micro-environment elicited by the elastase treatment favors cell death over proliferation.

Allograft vasculopathy is caused by chronic immune-mediated injury to the transplanted vasculature, leading to intimal smooth muscle cell accumulation, luminal narrowing, and eventual ischemic graft failure.31 However, in our transplant AAA model, we observed inflammatory cell infiltration without intimal hyperplasia, smooth muscle cell accumulation, or stenosis. This may be attributed to syngeneic transplantation and/or the short follow-up time period in this model. Many rodent studies have shown that recipient cells repopulate allografts.19, 32–34 Hagensen et al35 proved that the recipient source of endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells in allograft were from the flanking segments of the recipient vasculature. Although we found the majority of the mononuclear leukocytes were recruited from the recipient, a small but notable quantity of mononuclear leukocytes carried donor markers. These results suggest that, in addition to circulating cells, a certain population of vascular wall resident cells such as monocyte progenitors may also differentiate to leukocytes and then proliferate or undergo self-renewal, thus contributing to vascular inflammation in AAA disease.36 The origin of macrophages or macrophage-like cells in atherosclerotic lesion is an actively pursued topic. Additional to bone marrow-derived myeloid cells, other cell types including SMCs are suggested to give rise to a least a portion of macrophage-like cells.37 Phenotypic switching of SMCs to a synthetic or pro-inflammatory state has recently been noted in mouse models of cerebral aneurysm as well as AAA,38–40 which may offer an alternative explanation for these donor-derived CD68+ positive cells. Finally, the GFP+ macrophages in the GFP-to-WT transplant group might have acquired their green fluorescent signals by engulfing apoptotic SMCs within the donor aorta. However, this is unlikely because we did not find evidence of phagocytosis, for example, multiple nuclei in a single cell.

The reported elastase-induced transplantation AAA model has several limitations. Similar to the established elastase-infusion AAA model, our transplant model lacks several prominent features of the human lesion such as atherosclerosis and intraluminal thrombosis. It would be interesting to determine whether these atherosclerosis-like features could be depicted if apoE gene deficient mice are used as donors or recipients. Another limitation is that this model does not enable the identification of precise origin of recipient-derived cells.

In conclusion, we have developed a murine AAA model by orthotopic transplantation of elastase-treated abdominal aorta. This new model is a rapid and feasible tool to study pathophysiology of abdominal aortic aneurysm. As an alternative approach to BMC transplant, the aorta transplant AAA model avoids irradiation and thus may have a higher survival rate. This is important in particular considering high lethality in many transgenic mouse lines after irradiation.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Dr. Greenspan for providing microscope video recording system for this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: ZL, QW, SM, BL

Analysis and interpretation: ZL, QW, JR, CA, BL

Data collection: ZL, QW, JR, CA, JG, QH

Writing the article: ZL, QW, BL

Critical revision of the article: ZL, QW, JR, CA, SM, BL

Final approval of the article: ZL, QW, BL

Statistical analysis: ZL, QW

Obtained funding: BL

Overall responsibility: BL

REFERENCES

- 1.Baxter BT, Terrin MC, Dalman RL. Medical management of small abdominal aortic aneurysms. Circulation. 2008;117(14):1883–1889. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.735274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Powell JT, Brady AR. Detection, management, and prospects for the medical treatment of small abdominal aortic aneurysms. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2004;24(2):241–245. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000106016.13624.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weintraub NL. Understanding abdominal aortic aneurysm. The New England journal of medicine. 2009;361(11):1114–1116. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr0905244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mortality results for randomised controlled trial of early elective surgery or ultrasonographic surveillance for small abdominal aortic aneurysms. The UK Small Aneurysm Trial Participants. Lancet. 1998;352(9141):1649–1655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lederle FA, Wilson SE, Johnson GR, Reinke DB, Littooy FN, Acher CW, et al. Immediate repair compared with surveillance of small abdominal aortic aneurysms. The New England journal of medicine. 2002;346(19):1437–1444. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daugherty A, Cassis LA. Mouse models of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24(3):429–434. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000118013.72016.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thompson M, Cockerill G. Matrix metalloproteinase-2: the forgotten enzyme in aneurysm pathogenesis. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2006;1085:170–174. doi: 10.1196/annals.1383.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thompson RW. Basic science of abdominal aortic aneurysms: emerging therapeutic strategies for an unresolved clinical problem. Current opinion in cardiology. 1996;11(5):504–518. doi: 10.1097/00001573-199609000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ishibashi S, Goldstein JL, Brown MS, Herz J, Burns DK. Massive xanthomatosis and atherosclerosis in cholesterol-fed low density lipoprotein receptor-negative mice. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1994;93(5):1885–1893. doi: 10.1172/JCI117179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prescott MF, Sawyer WK, Von Linden-Reed J, Jeune M, Chou M, Caplan SL, et al. Effect of matrix metalloproteinase inhibition on progression of atherosclerosis and aneurysm in LDL receptor-deficient mice overexpressing MMP-3, MMP-12, and MMP-13 and on restenosis in rats after balloon injury. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1999;878:179–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gertz SD, Kurgan A, Eisenberg D. Aneurysm of the rabbit common carotid artery induced by periarterial application of calcium chloride in vivo. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1988;81(3):649–656. doi: 10.1172/JCI113368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daugherty A, Manning MW, Cassis LA. Antagonism of AT2 receptors augments angiotensin II-induced abdominal aortic aneurysms and atherosclerosis. British journal of pharmacology. 2001;134(4):865–870. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trollope A, Moxon JV, Moran CS, Golledge J. Animal models of abdominal aortic aneurysm and their role in furthering management of human disease. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2011;20(2):114–123. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pyo R, Lee JK, Shipley JM, Curci JA, Mao D, Ziporin SJ, et al. Targeted gene disruption of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (gelatinase B) suppresses development of experimental abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Clin Invest. 2000;105(11):1641–1649. doi: 10.1172/JCI8931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnston WF, Salmon M, Su G, Lu G, Stone ML, Zhao Y, et al. Genetic and pharmacologic disruption of interleukin-1beta signaling inhibits experimental aortic aneurysm formation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33(2):294–304. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morgan S, Yamanouchi D, Harberg C, Wang Q, Keller M, Si Y, et al. Elevated protein kinase C-delta contributes to aneurysm pathogenesis through stimulation of apoptosis and inflammatory signaling. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32(10):2493–2502. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.255661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Q, Ren J, Morgan S, Liu Z, Dou C, Liu B. Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 (MCP-1) Regulates Macrophage Cytotoxicity in Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e92053. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson RW, Curci JA, Ennis TL, Mao D, Pagano MB, Pham CT. Pathophysiology of abdominal aortic aneurysms: insights from the elastase-induced model in mice with different genetic backgrounds. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1085:59–73. doi: 10.1196/annals.1383.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shimizu K, Sugiyama S, Aikawa M, Fukumoto Y, Rabkin E, Libby P, et al. Host bone-marrow cells are a source of donor intimal smooth-muscle-like cells in murine aortic transplant arteriopathy. Nature medicine. 2001;7(6):738–741. doi: 10.1038/89121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dambrin C, Calise D, Pieraggi MT, Thiers JC, Thomsen M. Orthotopic aortic transplantation in mice: a new model of allograft arteriosclerosis. The Journal of heart and lung transplantation : the official publication of the International Society for Heart Transplantation. 1999;18(10):946–951. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(99)00051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shi C, Russell ME, Bianchi C, Newell JB, Haber E. Murine model of accelerated transplant arteriosclerosis. Circulation research. 1994;75(2):199–207. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koulack J, McAlister VC, Giacomantonio CA, Bitter-Suermann H, MacDonald AS, Lee TD. Development of a mouse aortic transplant model of chronic rejection. Microsurgery. 1995;16(2):110–113. doi: 10.1002/micr.1920160213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun H, Valdivia LA, Subbotin V, Aitouche A, Fung JJ, Starzl TE, et al. Improved surgical technique for the establishment of a murine model of aortic transplantation. Microsurgery. 1998;18(6):368–371. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2752(1998)18:6<368::aid-micr5>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chereshnev I, Trogan E, Omerhodzic S, Itskovich V, Aguinaldo JG, Fayad ZA, et al. Mouse model of heterotopic aortic arch transplantation. The Journal of surgical research. 2003;111(2):171–176. doi: 10.1016/s0022-4804(03)00039-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Calise D, Dambrin C, Labat A, Pieraggi MT, Pons F, Benoist H, et al. Orthotopic aortic transplantation in rodents by the sleeve technique: a model system for the study of graft vascular disease. Transplantation proceedings. 2001;33(3):2369–2370. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(01)02024-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ailawadi G, Eliason JL, Roelofs KJ, Sinha I, Hannawa KK, Kaldjian EP, et al. Gender differences in experimental aortic aneurysm formation. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2004;24(11):2116–2122. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000143386.26399.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ye P, Chen W, Wu J, Huang X, Li J, Wang S, et al. GM-CSF contributes to aortic aneurysms resulting from SMAD3 deficiency. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2013;123(5):2317–2331. doi: 10.1172/JCI67356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pucci AM, Forbes RD, Billingham ME. Pathologic features in long-term cardiac allografts. The Journal of heart transplantation. 1990;9(4):339–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adams DH, Russell ME, Hancock WW, Sayegh MH, Wyner LR, Karnovsky MJ. Chronic rejection in experimental cardiac transplantation: studies in the Lewis-F344 model. Immunological reviews. 1993;134:5–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1993.tb00637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mennander A, Raisanen A, Paavonen T, Hayry P. Chronic rejection in the rat aortic allograft. V. Mechanism of the angiopeptin (BIM23014C) effect on the generation of allograft arteriosclerosis. Transplantation. 1993;55(1):124–128. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199301000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mitchell RN, Libby P. Vascular remodeling in transplant vasculopathy. Circulation research. 2007;100(7):967–978. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000261982.76892.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu Y, Davison F, Ludewig B, Erdel M, Mayr M, Url M, et al. Smooth muscle cells in transplant atherosclerotic lesions are originated from recipients, but not bone marrow progenitor cells. Circulation. 2002;106(14):1834–1839. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000031333.86845.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu Y, Davison F, Zhang Z, Xu Q. Endothelial replacement and angiogenesis in arteriosclerotic lesions of allografts are contributed by circulating progenitor cells. Circulation. 2003;108(25):3122–3127. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000105722.96112.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hillebrands JL, Klatter FA, van den Hurk BM, Popa ER, Nieuwenhuis P, Rozing J. Origin of neointimal endothelium and alpha-actin-positive smooth muscle cells in transplant arteriosclerosis. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2001;107(11):1411–1422. doi: 10.1172/JCI10233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hagensen MK, Shim J, Falk E, Bentzon JF. Flanking recipient vasculature, not circulating progenitor cells, contributes to endothelium and smooth muscle in murine allograft vasculopathy. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2011;31(4):808–813. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.221184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Psaltis PJ, Harbuzariu A, Delacroix S, Witt TA, Holroyd EW, Spoon DB, et al. Identification of a monocyte-predisposed hierarchy of hematopoietic progenitor cells in the adventitia of postnatal murine aorta. Circulation. 2012;125(4):592–603. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.059360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gomez D, Owens GK. Smooth muscle cell phenotypic switching in atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc Res. 2012;95(2):156–164. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Starke RM, Chalouhi N, Ding D, Raper DM, McKisic MS, Owens GK, et al. Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells in Cerebral Aneurysm Pathogenesis. Transl Stroke Res. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s12975-013-0290-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Airhart N, Brownstein BH, Cobb JP, Schierding W, Arif B, Ennis TL, et al. Smooth muscle cells from abdominal aortic aneurysms are unique and can independently and synergistically degrade insoluble elastin. J Vasc Surg. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.07.097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Branchetti E, Poggio P, Sainger R, Shang E, Grau JB, Jackson BM, et al. Oxidative stress modulates vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype via CTGF in thoracic aortic aneurysm. Cardiovascular research. 2013;100(2):316–324. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.