Abstract

The functions of specific microorganisms in a microbial community were investigated during the composting process. Cerasibacillus quisquiliarum strain BLxT and Bacillus thermoamylovorans strain BTa were isolated and characterized in our previous studies based on their dominance in the composting system. Strain BLxT degrades gelatin, while strain BTa degrades starch. We hypothesized that these strains play roles in gelatinase and amylase production, respectively. The relationship between changes in the abundance ratios of each strain and those of each enzyme activity during the composting process was examined to address this hypothesis. The increase in gelatinase activity in the compost followed a dramatic increase in the abundance ratio of strain BLxT. Zymograph analysis demonstrated that the pattern of active gelatinase bands from strain BLxT was similar to that from the compost. Gelatinases from both BLxT and compost were partially purified and compared. Homologous N-terminal amino acid sequences were found in one of the gelatinases from strain BLxT and that of compost. These results indicate strain BLxT produces gelatinases during the composting process. Meanwhile, the increase in the abundance ratio of strain BTa was not concurrent with that of amylase activity in the compost. Moreover, the amylase activity pattern of strain BTa on the zymogram was different from that of the compost sample. These results imply that strain BTa may not produce amylases during the composting process. To our knowledge, this is the first report demonstrating that the function of a specific microorganism is directly linked to a function in the community, as determined by culture-independent and enzyme-level approaches.

The structures of microbial communities in various environments have been analyzed ever since culture-independent approaches were introduced into microbial ecological studies. The culture-independent approach has enabled us to obtain abundant information about the structures of microbial communities that had been previously explored only by culture-dependent strategies (1). In microbial ecological studies, however, it is important to understand the relationship between the structures and functions of microbial communities (41, 42).

Numerous studies in various environments have reported links between community structure and function. Metcalfe et al., while discussing the diversity of chitinases in soil, reported that the genus Streptomyces played an important role in the degradation of a bait chitin bag (23). Manefield et al. pointed out, through RNA stable-isotope probing, that a potentially novel species belonging to the genus Thauera occurred actively and predominantly during phenol degradation in a phenol-degrading bioreactor (22). Pinhassi et al. reported the succession of a microbial community triggered by protein enrichment in the aquatic environment (33). They analyzed microbial succession by whole-genome hybridization between environmental DNA and DNA from pure cultures and transitions of enzyme activities by using fluorescence-labeled substrates. They proposed a link between the shifts in the structure and function of the community. However, they also recognized that it was difficult to prove the causal relationships until the proteolytic activity was directly related to the enzyme producer.

In the case of the composting process, many studies have been performed with both culture-dependent and culture-independent approaches to analyze the structure of the microbial community. The diversity of microorganisms during the composting process was examined by cultivation-isolation-based techniques (3, 4, 9, 10, 11, 35, 36, 37). The community structure was investigated with both PCR-based and cultivation-isolation-based techniques (8, 31, 32). The succession of the microbial community was observed with PCR-based techniques (12, 17, 30, 31, 32). Using other biomarkers, including phospholipid fatty acids and lipoquinones, succession of the microbial community was examined (13, 15). A polyphasic study with different kinds of approaches showed its importance to reveal the structure of the microbial community (16). However, compared to this large number of studies, few relating structure to the function of a community have been reported (11, 19, 40). Tiquia et al. showed a shift in the community structure and enzyme activity during composting. These results support the previous reports demonstrating that fungi and actinomycetes may degrade cellulose and hemicellulose, as determined from the high positive correlation between the number of those microorganisms and β-glucosidase activity. However, none of the studies elucidated the causal relationships directly linking extracellular enzymes decomposing solid substrates to the microbial community, despite the fact that these enzymes are of primary importance for composting (40). Microorganisms must decompose insoluble (solid) substrates of organic matter using hydrolytic extracellular enzymes (and/or membrane-bound enzymes) to the extent that the decomposed substances are able to pass across the cytoplasmic membranes (11).

Based on results of our previous studies, we have been focusing on two specific microorganisms by using a semicontinuous system for composting of kitchen refuse (12, 26). Cerasibacillus quisquiliarum strain BLxT was reproducibly detected by denaturant gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) analysis and accounted for 30% of the bacterial cells as determined by fluorescent in situ hybridization analysis. Moreover, 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) sequences homologous to that of strain BLxT were reported in other composting and wastewater treatment processes (17, 20). Based on this information, strain BLxT was assumed to be a common member of composting communities and to play some important role(s) during the organic (solid)-waste treatment process. Therefore, we are quite interested in elucidating the function(s) of strain BLxT in the composting process. However, the ability of strain BLxT to assimilate carbohydrates and degrade biopolymers is rather poor compared with species in the family Bacillaceae that were frequently found during composting, such as the well-characterized Bacillus subtilis, Bacillus licheniformis, and Geobacillus stearothermophilus (a synonym of Bacillus stearothermophilus) (36). Strain BLxT degrades gelatin and assimilates a few sugars and carboxylic acids.

The other microorganism, strain BTa, which is thought to belong to Bacillus thermoamylovorans based on 16S rDNA analysis, was also found reproducibly in the DGGE profile and accounted for 40% of the bacterial cells before strain BLxT appeared. Strain BTa degrades starch and assimilates certain kinds of sugars. We are interested in determining the functions of these dominant strains within the microbial community during the composting process.

In this study, we investigated the relationship between the dominant members of the microbial community and their roles in the decomposition of biopolymers. We hypothesized that these strains play significant roles as extracellular gelatinase and amylase producers, respectively, during the composting process. Therefore, our system provides a good model for investigating the relationships between the structure and function of the microbial community. To our knowledge, this is the first report demonstrating that the function of a specific microorganism is directly linked to their function in the community at the enzyme (protein) level during the decomposing process for solid waste. The results of this study provide considerable insight for discussions of the relationship between structure and function within microbial communities.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Running conditions for composting system for kitchen refuse and collection of samples.

The laboratory scale composting system for kitchen refuse had agitation wings stirring the compost for 4 min at 30-min intervals. The total volume of the composting system was ∼30 liters. The airflow rate into the composting system was shifted to 15 to 40 liters per min to control the moisture content (at ∼40%) of the compost. Sawdust (10 liters; Biowogran; Morishita Kikai, Wakayama, Japan) was added as a starting material to provide an initial moisture content of 40%. Every day, we supplied standard kitchen refuse comprised of the following components: 36% vegetable components (18% cabbage and 18% carrot), 30% fruit (16% banana and 14% apple), and 34% other organic components (10% fried chicken, 10% dried fish, 10% boiled rice, and 4% used tea leaves). The refuse contained ∼75 to 78% moisture content and 44% carbon and 4% nitrogen as dry weight and had a pH value of 6 to 7. The temperature of the decomposed matter was measured every 30 min with an automatic recording thermometer. Compost samples (>100 g) were taken from at least four points in the system during stirring by the agitation wings on days 2.5, 3.5, 4.5, 5.5, 6.5, 8.5, 13.5, 16.5, 20.5, 23.5, 27.5, 30.5, 35.5, and 42.5. (Day X.5 means that sampling was done 12 h after the addition of refuse on day X.) The collected samples were spread onto a plastic wrap and mixed thoroughly with a spoon before the division for each measurement. On day 36 (just before the addition of refuse), ∼3 kg of compost was removed from the system, and then 5 liters of new sawdust was applied in order to recover the decomposing efficiency (see Results). The collected samples were divided for each measurement. For pH measurement, 4 g of sample was added to 40 ml of distilled water and then mixed with hand shaking at 180 rotations per minute for 5 min at room temperature. The supernatant was obtained after centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 5 min. The pH value of the supernatant was measured with a pH meter (HI 9811; HANNA Instruments). The supernatant was also used as a crude protein extract. The moisture contents of samples (10 g) were measured with an electronic moisture balance (MOC-30S; Shimadzu Co., Ltd., Kyoto, Japan). For DNA extraction of the microbial community, 10 g of sample was homogenized in 80 ml of DNA extraction buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl at pH 9.0 and 40 mM EDTA) (12) with a POLYTRON homogenizer (Kinematica, Littau/Lucerne, Switzerland) at 15,000 rpm for 5 min on ice. An aliquot of each homogenized sample was stored in a 1.5-ml centrifuge tube at −20°C.

The number of bacterial cells was determined by using fluorescence microscope counts and plate cultivation. Ten grams of each sample was homogenized in 80 ml of saline (0.85% NaCl) as described above. Homogenized samples were serially diluted with saline. Diluted samples were applied to microscope slides for cell counts or spread onto tryptic soy agar (TSA) plates (tryptic soy broth [TSB; Difco] containing 1.5% [wt/vol] agar). Four plates of each diluent from days 6.5, 13.5, 20.5, 27.5, and 42.5 were incubated at 37°C for 1 week. The number of CFU in the plates on which ∼100 colonies grew was evaluated. The number of bacterial cells was determined using the fluorescence microscope on days 3.5, 6.5, 8.5, 13.5, 20.5, 27.5, 35.5, and 42.5 as reported previously (15), except that a LIVE/DEAD BacLight Bacterial Viability kit (Molecular Probes) was used, following the manufacturer's instructions.

Bacterial strains, media, and growth conditions.

C. quisquiliarum strain BLxT was cultivated on TSA (pH 8.5) at 37°C for 4 days. One loopful of cells was suspended in 5 ml of TSB (pH 8.5) and incubated at 50°C with shaking at 120 rpm. An overnight culture was inoculated into 50 ml of TSB in a 500-ml shaking flask and incubated at 50°C with shaking at 120 rpm. Cultivation was stopped at early stationary phase, and the culture was centrifuged at 9,600 × g and 4°C for 15 min. Precipitated cells were washed twice with saline, suspended in DNA extraction buffer, and stored at −20°C for DNA preparation. The culture supernatant of strain BLxT was used for protein analysis. A strain whose closest relative was B. thermoamylovorans (L27478) (7) on the basis of 16S rDNA sequence (AB121094) was isolated and was regularly found on plates during the decomposing process. The strain, designated BTa, was cultured on TSA (pH 8.5) at 50°C overnight. One loopful of colony material was suspended in 5 ml of TSB (pH 8.5) and incubated at 50°C with shaking at 120 rpm overnight. Cells were recovered by centrifugation at 9,600 × g and 4°C for 15 min. After being washed twice with saline, the cells were suspended in DNA extraction buffer and stored at −20°C for DNA preparation. For protein analysis, strain BTa was cultured in TSB (pH 7.3) including 2.5% (wt/vol) soluble starch and 0.2% (wt/vol) CaCO3 at 37°C for 2 days with shaking at 120 rpm. The culture supernatant was obtained after centrifugation and used for enzyme assays.

Design of specific primers.

A specific primer for strain BLxT was BL4F (5′-AGTGATGAATGTCTTCGGATTGTAAAA-3′; Escherichia coli numbering, 414 to 440) constructed on the basis of 16S rDNA sequence. BL4F was complementary to the BLxT-specific probe PB_BX414 (12). A primer, 907R-BLx (5′-CCCCGTCAATTCTTTTGAGTTT-3′; E. coli numbering, 928 to 907), was a modification of the sequence of a conventional primer for DGGE analysis (926r; the underlined position was changed) (25). These two primers were used for quantitative real-time PCR.

Specific primers for strain BTa were designed on the basis of 16S rDNA sequence by using a probe-primer-designing program, PRIMROSE (2). The primers were constructed within an aligned database (updated on 28 August 2002) of prokaryotes' SSU rRNA downloaded from the Ribosomal Database Project II (http://rdp.cme.msu.edu/download/SSU_rRNA/alignments/). Two specific primers were successfully generated, BTA190F (5′-GGAGAGATAAGGAAAGATGG-3′; E. coli numbering, 183 to 202) and BTA482R (5′-CAAGGTACCGGCATTTCCTC-3′; E. coli numbering, 462 to 481).

Measurement of the abundance ratios of specific microorganisms by quantitative real-time PCR.

Microbial-community DNA and DNAs from isolated strains were extracted from frozen samples by the benzyl chloride method (44). The crude DNA preparations were extracted with Tris-HCl (pH 8.0)-saturated phenol and chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (24:1). Nucleic acids were precipitated with isopropanol, and the resulting pellets were incubated in 100 μl of TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0] and 1 mM EDTA) at 4°C overnight. After incubation, 5 μl of RNase A (2 mg/ml) was added, and the solution was incubated at 37°C for 30 min. The same amount of 2× polyethylene glycol-NaCl (20% polyethylene glycol and 0.6 M NaCl) was added, and the solution was mixed gently and let stand at 4°C overnight. DNA pellets were recovered after centrifugation at 17,000 × g and 4°C for 20 min. The DNA pellets were washed with cold 70% ethanol and dried in a vacuum. The dried pellets were suspended in 100 μl of TE buffer. The DNA concentration of each sample was determined with a Fluorescent DNA Quantification kit (Bio-Rad) and a VersaFluor fluorometer (Bio-Rad) by following the manufacturer's recommendations.

A quantitative real-time PCR strategy was applied to measure the abundance ratios of the specific microorganisms, strains BLxT and BTa, in the microbial community using the LightCycler (Roche) and LightCycler-FastStart DNA Master SYBR Green I (Roche). Amplification was performed in a 10-μl final volume containing 3 mM MgCl2, 1 μl of 10× LightCycler-FastStart DNA Master SYBR Green I, 1 μl of DNA template, and 0.5 μM specific primers for each strain. The amplification program for strain BLxT included the following: one cycle of denaturation, which was accomplished by heating at 20°C/s to 95°C with a 10-min hold, and 35 cycles of the PCR program, which was comprised of three steps of heating at 20°C/s to 95°C with a 15-s hold, cooling at 20°C/s to 68°C with a 6-s hold, and heating at 2°C/s to 72°C with a 20-s hold. The amplification program for strain BTa included the following: one cycle of denaturation by heating at 20°C/s to 95°C with a 10-min hold and 35 cycles of the PCR program, which was comprised of four steps of heating at 20°C/s to 95°C with a 15-s hold, cooling at 20°C/s to 58°C with a 6-s hold, heating at 2°C/s to 72°C with a 15-s hold, and heating at 20°C/s to 86°C with a 1-s hold. Fluorescent products were detected in the last step of each cycle. After amplification, melting curves were obtained by heating at 1°C/s to 95°C, cooling at 20°C/s to 70°C, and slowly heating at 0.1°C/s to 95°C with fluorescent collection at 0.1°C intervals. Melting curves were used to determine the specificity of the PCR (34). The specificity of the PCR for each strain was also confirmed by sequencing the amplified product from the compost sample.

DNA mass-based standard curves for each strain were generated with genomic DNA from each strain (164 fg, 1.65 pg, 165 pg, and 16.5 ng of genomic DNA from strain BLxT and 18.7 fg, 1.87 pg, 187 pg, and 18.7 ng of DNA from strain BTa). Using these standard curves, the DNA mass for each strain present in the samples was calculated. The abundance ratios of the strains were represented as percentages from the DNA masses of samples (ranging from 123 pg to 1.53 ng). At least triplicate trials were performed to generate each standard curve or to obtain each abundance ratio.

Sample preparation for protein analysis.

Culture supernatants of strain BLxT and strain BTa, or crude protein extracts from compost samples, were filtered with 0.45-μm-pore-size membrane filters and concentrated 10-fold with a centrifugal concentrator (Vivaspin 10k MWCO; Sartorius). Protein concentrations were determined by the Bio-Rad protein assay following the manufacturer's instructions.

Assay of gelatinase activity and activity staining of gelatinases.

Gelatinase activity was determined by two methods. The Azocoll method was applied to measure the total activity (6, 27), and zymography was introduced to profile the molecular species of gelatinase (24). Azocoll (<50 mesh; Calbiochem), 0.25 g, was suspended in 50 ml of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.8) buffer containing 1 mM CaCl2 and incubated at 50°C for 90 min. The Azocoll suspension was then filtered with glass fiber filter paper (GA140; Toyo Roshi K., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The Azocoll remaining on the filter was collected and resuspended in 50 ml of the same buffer. Sample (30 μl) was added to the Azocoll suspension (300 μl) in 2-ml round-bottom plastic tubes and incubated at 50°C and 1,250 rpm for 1 h using a mixing incubator (BioShaker M · BR-022; TAITEC, Tokyo, Japan). The supernatant was obtained after centrifugation at 17,000 × g and 4°C for 10 min. The absorbance of the supernatant at 540 nm was measured with a spectrophotometer (DU 7400; Beckman Coulter). One unit of gelatinase activity was represented as 1 A540 unit increase in 1 h.

In order to compare the gelatinase profiles, the same amount of each sample based on the gelatinase activity obtained by the Azocoll method was incubated with sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer at room temperature for 30 min. Samples in SDS sample buffer were applied to SDS-polyacrylamide gels (13.5% [wt/vol] acrylamide) and electrophoresed at room temperature and at a constant voltage of 100 V for 165 min. After electrophoresis, the gel was washed in 2.5% Triton X-100-10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0) for 1 h to remove the SDS. The gel was soaked in 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0) for a few minutes and put onto a filter paper that had been soaked in the same buffer. A gel (12% polyacrylamide; 1 mm thick) containing 0.5% gelatin was then wrapped over the soaked gel, and absorbent filter paper was put onto the gelatin-gel. The filter paper-gel sandwich was wrapped with cling wrap, pressed under a glass plate, and incubated at 50°C for 15 h. The gelatin-gel was then stained with 0.1% amide black in 30% methanol, 10% acetic acid, and 60% water. The profile of gelatinases was visualized on the gel as clear zones resulting from the hydrolysis of the gelatin after destaining with 10% acetic acid.

Purification of gelatinases.

Gelatinases from the culture supernatant of strain BLxT or those from crude protein extracts on day 13.5 were partially purified by the following three steps. The gelatinase activity was assayed by the Azocoll method. Precipitation of proteins by the addition of ammonium sulfate (final concentration, 3.2 M) was performed. The precipitants were dissolved in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) buffer (buffer T). Secondly, the dissolved fractions were applied to a DEAE-Sepharose Fast Flow column (1.0 by 5.0 cm) equilibrated with buffer T, and adsorbed proteins were eluted with a linear gradient of NaCl (0 to 0.5 M) in buffer T. Finally, after all active fractions were combined, followed by dialysis against buffer T, samples were mixed with the same amount of 2 M ammonium sulfate and applied to a Phenyl-Sepharose Fast Flow column (1.0 by 5.0 cm) equilibrated with buffer T containing 1 M ammonium sulfate. The adsorbed proteins were eluted with a descending linear gradient of ammonium sulfate (1 to 0 M) in buffer T, and active fractions were combined and dialyzed against buffer T. The gelatinase profiles of crude and partially purified gelatinases were compared by the activity-staining method. The N-terminal amino acid sequences of gelatinases with the smallest molecular weights from each partially purified sample were determined by using an Applied Biosystems 491 cLC protein sequencer.

Assay of amylase activity and activity staining of amylases.

Amylase activity was determined by two methods. Amylase activity was assayed on the basis of the starch-iodometric method (5), and zymography was introduced to profile the molecular species of amylase (29). The culture supernatant of strain BTa or crude protein extracts of compost samples were diluted appropriately, and an aliquot (10 μl) of each dilution was incubated with stably buffered starch substrate (pH 7.0; 100 μl) in a 96-well microplate at 50°C for 1 h. Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride was added to the reaction mixture (final concentration, 2.5 mM) to inhibit protease activity in the compost samples. The reaction was stopped with 100 μl of 0.01 N iodine solution. The activity was estimated by measuring the dark-blue color at 650 nm. The absorbance of samples at 650 nm (sample absorbance) was measured with a microplate reader (Emax precision microplate reader; Molecular Device). The absorbance of sample without substrate (background absorbance) was measured after the addition of water (100 μl) and iodine solution (100 μl) for correction of background. The difference between the sample absorbance and the background absorbance was calculated. Residual amounts of starch in the reaction mixtures were obtained from a standard curve of different concentrations of starch solution (0 to 0.4 mg/ml). One unit of activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that catalyzed the hydrolysis of 1 mg of starch in 1 h.

In order to compare the amylase profiles, the same amount of each sample based on the activity determined by the starch-iodometric method was mixed with sample buffer. Samples in sample buffer were loaded on native polyacrylamide gels (10.5% [wt/vol]) and electrophoresed at room temperature and at a constant voltage of 100 V for 120 min. After electrophoresis, the gel was soaked in 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.1) buffer containing 5 mM CaCl2 (buffer H) and incubated at room temperature for 30 min with shaking. Then, the gel was immersed in buffer H containing 1.5% soluble starch and incubated at 50°C for 1 h with shaking. The gel was rinsed with buffer H, soaked in 0.01 N iodine solution, and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. The amylase profiles were visualized on the gel as clear zones resulting from the hydrolysis of the starch after the gel was rinsed with buffer H.

RESULTS

Properties of the compost during operation.

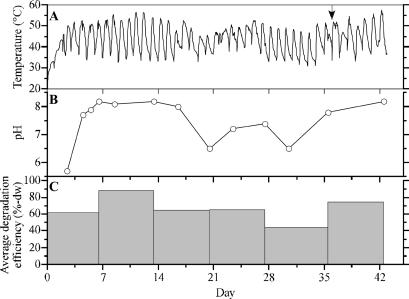

The temperature of the compost changed during the course of each day throughout the operation, because we added standard kitchen refuse every day (Fig. 1A). The temperature increased from ∼35 to 50°C (up to ∼55°C) within 10 h of the addition of refuse and then decreased to ∼35°C. It was thought that the microorganisms in the compost exhausted their available substrates within several hours. The changes in the pH of the compost are shown in Fig. 1B. At the start of the operation, the pH was acidic, and it subsequently changed to alkaline. Alkaline conditions lasted for ∼10 days (from days 6.5 to 16.5). Afterward, it became approximately neutral, and this condition lasted for 10 days (from days 20.5 to 30.5). The average degradation efficiency was expressed as a percentage on the basis of the dry-weight loss of applied refuse (Fig. 1C). The efficiency reached ∼90% during the second week of operation but gradually decreased afterward. It declined to ∼44% in the fifth week. This decline could have resulted from the deterioration of the sawdust. Wear of the sawdust by continuous stirring could cause the destruction of the spongy structure, and this could inhibit aeration within the system. On day 36, just before the addition of refuse (Fig. 1A), a portion of the compost was removed and new sawdust was added. After this time, the pH of the compost became alkaline, and the degradation efficiency recovered to ∼75%.

FIG. 1.

Physical parameters of compost and degradation efficiency of kitchen refuse during the composting process. (A) Transition of temperature within compost. The arrow indicates day 36, when a portion of the compost was removed and new sawdust was added. (B) Transition of pH within the compost. (C) Degradation efficiency during the composting process. The average degradation efficiency for ∼7 days was calculated based on the dry weight (dw).

Cell count analysis.

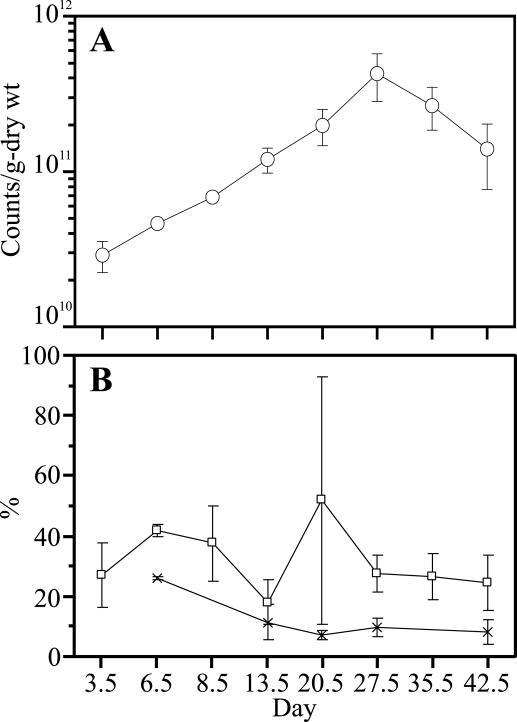

Cell count analysis was performed by microscopic and cultivation-based methods to reveal the changes in the number of bacteria during the composting process. Figure 2 shows the results of cell count analysis. Total cell counts gradually increased until day 27.5 and ranged from 2.89 × 1010 to 4.28 × 1011 per g (dry weight) during the composting process. The decrease in the total cell count on day 35.5 may have caused the deterioration of the degradation efficiency in the fifth week. Because the compost was diluted by the introduction of new sawdust on day 36, the total cell count on day 42.5 decreased. The viable cell count accounted for 18 to 52% of the total cell count during the operation. CFU accounted for 7.1 to 26% of the total count.

FIG. 2.

Microbial counts during the composting process. (A) Total counts were obtained from epifluorescence microscopic counts with BacLight (the sum of live cells and dead cells). The average of counts on three individual membranes was calculated. The error bars indicate standard errors. (B) Viability and culturability during the composting process. Viability (□) was expressed as a percentage of viable cell counts per total count obtained from microscopic counts. Culturability (×) was expressed as a percentage of CFU on TSA plates at 37°C per total count. The error bars indicate standard errors (n = 3 [viability] and n = 4 [culturability] CFU per total count).

Abundance ratio of strain BLxT and gelatinase activity in compost.

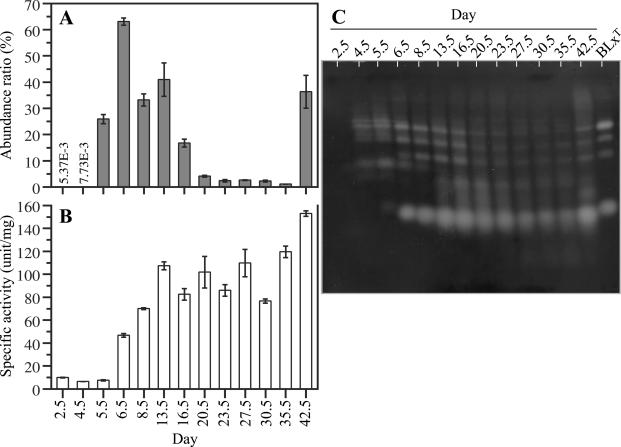

The change in the abundance ratio of strain BLxT was obtained by quantitative real-time PCR analysis, as shown in Fig. 3A. The abundance ratio increased dramatically on day 5.5, although it was <0.01% before that time. Strain BLxT was dominant until day 16.5, ranging from 17 to 63% of the total community DNA. Then the abundance ratio decreased to <5% from day 20.5 to day 35.5. After the addition of sawdust, strain BLxT increased again to 40%. When strain BLxT was detected at a high abundance ratio, the pH of the compost was alkaline (Fig. 1B and 3A). Moreover, the pH of the compost on day 20.5 was 6.5 when the abundance ratio dropped to 4.2%. This phenomenon was reasonable because strain BLxT is alkaliphilic (26). Moreover, the degradation efficiency was relatively high when the abundance ratio of strain BLxT was high (Fig. 1C and 3A). The degradation efficiency was 88% during the second week, when the abundance ratio of strain BLxT ranged from 33 to 63%, and then it declined to 44% in the fifth week, when the abundance ratio of strain BLxT ranged from 1.1 to 2.6%. On day 42.5, the abundance ratio of strain BLxT increased to 36% and the degradation efficiency recovered to 75%. This result supports the hypothesis that strain BLxT contributes to decomposition in the compost.

FIG. 3.

Changes in the abundance ratio of strain BLxT and gelatinase activity during the composting process. (A) The abundance ratio of strain BLxT is represented as the DNA mass ratio (the DNA mass of strain BLxT per DNA mass of the compost sample). The DNA mass of strain BLxT was obtained from the quantitative real-time PCR-targeted 16S rDNA of strain BLxT with a LightCycler system and genomic DNA from strain BLxT. The error bars indicate standard errors (n ≥ 3). (B) Gelatinase activity was assayed with Azocoll as the substrate. The error bars indicate standard errors (n = 3). (C) Zymogram of gelatinase activities of compost samples and strain BLxT culture supernatant with gelatin as the substrate. Each sample applied to the zymograph had the same number of gelatinase units based on the Azocoll assay.

Changes in gelatinase activity over time are shown in Fig. 3B. An increase in gelatinase activity in the compost was observed on day 6.5. Gelatinase activity increased gradually until day 13.5 and did not vary significantly after that. Zymographic analysis was carried out in order to follow the succession of molecular species of gelatinase (Fig. 3C). Equal amounts of gelatinase activity units based on the specific activity in Fig. 3B were applied to zymographs. Clear bands on a black background demonstrate gelatinase activity. Several molecular species of gelatinase were detected, and the patterns of gelatinase activity bands varied from day 4.5 to day 13.5. The patterns were quite similar after that, but the intensities of the bands were different. The culture supernatant of strain BLxT was also applied to this zymograph (Fig. 3C, rightmost lane), and the gelatinase pattern was similar to those of the compost after day 6.5. These results imply that strain BLxT produced gelatinases during the composting process, although there was a time lag between the increase in the abundance ratio of strain BLxT and increased gelatinase activity. This time lag could be explained by the relationship between the growth phase of strain BLxT and its gelatinase production. Gelatinase production in strain BLxT was higher during late exponential phase than in early exponential phase, when it was tested in a tube (data not shown). Both the increase in gelatinase activity following the increase in the abundance ratio of strain BLxT and similar gelatinase patterns in compost samples on days when the abundance ratio of strain BLxT dominated and the culture supernatant of strain BLxT were also observed in another operation. In order to identify the protein(s) responsible for these activities, gelatinases from the crude protein extract on day 13.5 and from strain BLxT were purified.

Purification and comparison of gelatinases from strain BLxT and the compost sample.

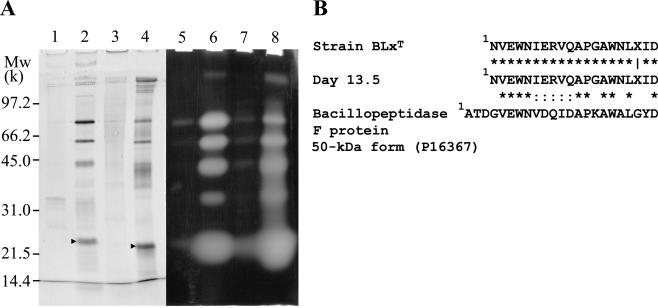

After several purification steps, gelatinases were partially purified and compared by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis-Coomassie brilliant blue (CBB) staining and zymography (Fig. 4A). The same amount of protein from each sample (10 μg) was applied. After purification, the patterns of gelatinase activity in protein bands from strain BLxT and crude protein extract from compost on day 13.5 were almost identical (Fig. 4A, compare lanes 6 and 8), and some bands corresponding to activity bands were detected by CBB staining (Fig. 4A, compare lanes 2 and 6 and lanes 4 and 8). The N-terminal amino acid sequences of the bands (∼23.5 kDa) were determined (Fig. 4A, lanes 2 and 4). These bands had identical sequences up to 19 amino acid residues from the N termini, except for the 19th residue, X (Fig. 4B). These results indicate that strain BLxT excreted a gelatinase during composting. The bacillopeptidase F protein (50-kDa form) was the most similar protein in the public databases (SwissProt no. P16397) (43). This protein is an alkaline serine protease from B. subtilis. Gelatinase activities from each sample were recovered from almost the same fractions during the purification steps. Moreover, no gelatinase activities were found in other fractions (data not shown). These results imply that most of the gelatinases present in the compost sample were produced by strain BLxT at least on day 13.5. Therefore, strain BLxT was shown to play a major role as a gelatinase producer.

FIG. 4.

Comparison of gelatinases present in strain BLxT and the compost sample. (A) CBB-stained gel and zymograph gel. Samples were applied in equal amounts (10 μg of protein). Crude enzyme in culture supernatant from strain BLxT (lanes 1 and 5) and crude protein extract on day 13.5 (lanes 2 and 7) were applied. After the phenyl-Sepharose purification step, partially purified samples were applied (strain BLxT, lanes 2 and 6; compost sample, lanes 4 and 8). N-terminal amino acid sequences were determined for the bands indicated by arrowheads. (B) Comparisons of the N-terminal amino acid sequences in gelatinases from strain BLxT and the compost sample on day 13.5 and between these gelatinases and bacillopeptidase F protein. Symbols: *, identical amino acid residues; :, positive residues defined by BLAST homology search analysis through the DNA Data Bank of Japan website (BLOSUM62 was selected as a scoring matrix for probability calculation of amino acid substitution); , unidentified residue.

Abundance ratio of strain BTa and amylase activity in compost.

In addition to strain BLxT, the relationship between strain BTa and amylase activity was examined. Amylase production was thought to be a key function for this microorganism, because strain BTa does not produce other hydrolytic enzymes (protease, gelatinase, cellulase, or lipase) (data not shown). As observed in a previous study (12), several colonies whose morphologies were similar to that of strain BTa were found on TSA plates from day 6.5 (data not shown). Conditions for specific PCR for strain BTa were developed, and the specificity was examined. When melting-curve analysis was applied to the amplified sample, an unfavorable by-product (primer dimer) was observed. Therefore, a higher detection temperature (86°C) than that used for strain BLxT (72°C) was introduced in order to eliminate the detection of the by-product (18).

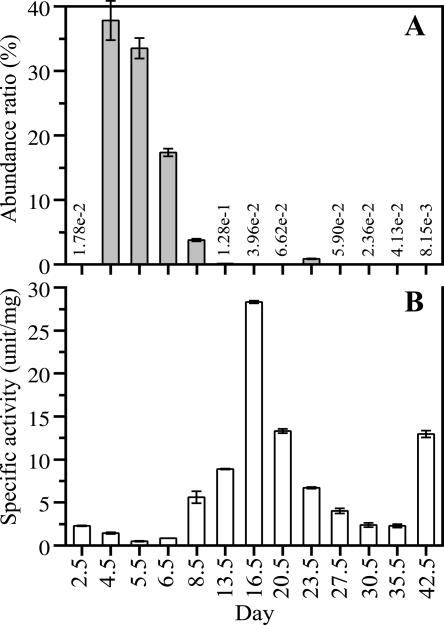

The abundance ratio of strain BTa increased drastically on day 4.5, subsequently decreased, and finally became <1% after day 13.5 (Fig. 5A). Meanwhile, there was no dramatic increase in amylase activity from day 4.5 to day 6.5, when a high abundance ratio of strain BTa was observed (Fig. 5B). Instead, an increase in amylase activity was observed on day 8.5, and it was significantly higher on day 16.5, when the abundance ratio of strain BTa declined to <1%. Amylase activity decreased gradually until day 35.5. After the replacement of the sawdust, activity recovered on day 42.5.

FIG. 5.

Changes in the abundance ratio of strain BTa and amylase activity during the composting process. (A) The abundance ratio of strain BTa is represented as the DNA mass ratio (the DNA mass of strain BTa per DNA mass of the compost sample). The DNA mass of strain BTa was obtained from quantitative real-time PCR-targeted 16S rDNA from strain BTa with a LightCycler system and genomic DNA from strain BTa. The error bars indicate standard errors (n ≥ 3). (B) Amylase activity was measured by the starch-iodometric method. The error bars indicate standard errors (n = 3).

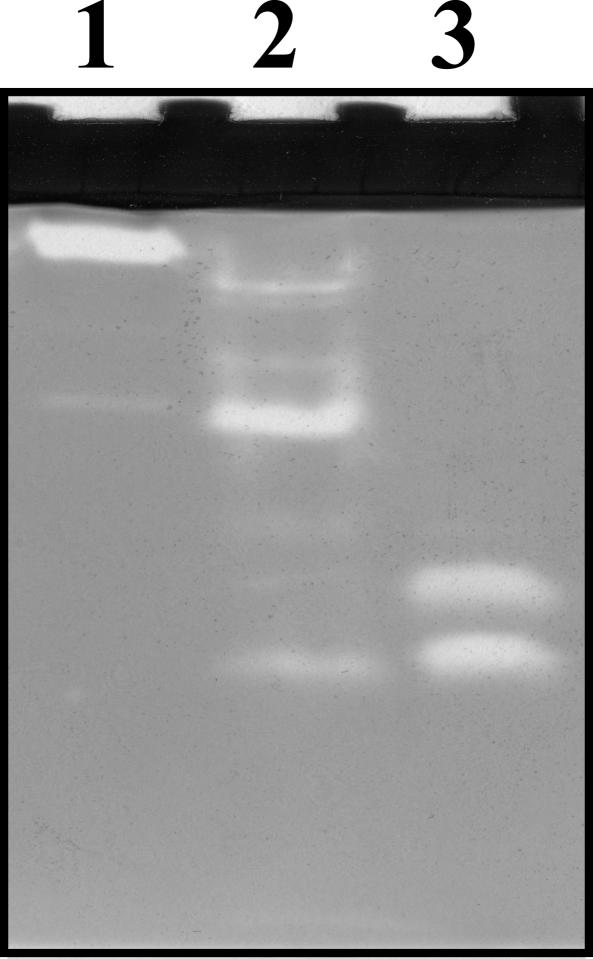

The drastic increase in the abundance ratio of strain BTa was not concurrent with the increase in amylase activity. Moreover, zymograph analysis showed different amylase activity patterns in the culture supernatant of strain BTa and in compost samples (days 4.5 and 16.5) (Fig. 6). These phenomena were also observed at another operation (data not shown). These results indicate that strain BTa might not produce amylase on days 4.5 and 16.5 and that other microorganisms producing amylase proliferated during the composting process.

FIG. 6.

Zymogram of amylase activities of the compost samples and strain BTa culture supernatant with soluble starch as a substrate. All samples applied to the zymograph contained equal amounts of amylase activity units as determined by the starch-iodometric assay. Lane 1, culture supernatant from strain BTa; lane 2, compost sample on day 4.5; lane 3, compost sample on day 16.5.

DISCUSSION

Changes in the abundance ratio of strain BLxT and culturability during composting.

Strain BLxT has been found relatively infrequently on plates (12, 26). Cell viability could be one of the reasons for this phenomenon (Fig. 2 and 3A). Quantitative real-time PCR analysis revealed that the abundance ratios of strain BLxT were 63 and 41% on day 6.5 and day 13.5, respectively. Viable counts were 42 and 18% on day 6.5 and day 13.5, respectively. A few colonies with morphologies similar to that of strain BLxT were found on plates on day 6.5 out of a total of 52 colonies, but on day 13.5, none of the 65 colonies resembled strain BLxT. One of the similar colonies from day 6.5 was confirmed to be phylogenetically identical to strain BLxT (data not shown). Alternatively, the viability of cells may have changed within a day in our system, as indicated by Kurisu et al., who analyzed the microbial community in a model wastewater treatment system with daily feeding of substrate (20). These authors reported daily temperature transitions that were similar to those observed in our system, and large numbers of metabolically active cells were observed at times before the temperature reached a peak, and then the cells became inactive. They indicated that some species in the community might become active immediately after feeding and become inactive after depletion of substrate or under other conditions. Based on this information, strain BLxT might be active early in the day (before the peak in temperature), although the cells became inactive at sampling time (a few hours after the peak in temperature). However, other reasons accounting for the low abundance of strain BLxT on the agar plates may remain to be discovered.

Culturability (numbers of CFU per total counts) in this study was significantly lower than that reported by other researchers who used a similar semicontinuous composting system. Narihiro et al. and Hiraishi et al. reported high culturability (54 and 60%, respectively) at the steady state of composting (32 and 56 days after waste loading, respectively) using several kinds of personal electronic fed-batch composting systems and a flowerpot-using solid-biowaste composting system, respectively (16, 28). The difference may result from different community structures, cultivation conditions, and/or physicochemical conditions during composting processes.

Strain BLxT produces gelatinases during composting.

The combination of results from quantitative real-time PCR analysis and protein analysis revealed that strain BLxT produced gelatinase(s) during composting. Gelatinase activity did not decrease on day 20.5, however, when the abundance ratio of strain BLxT declined to 6.2% (Fig. 3A and B). On the other hand, zymograms showed that the intensities of activity bands decreased after day 20.5 until day 35.5, although the same number of gelatinase units that was obtained from Azocoll degradation was applied to zymograph analysis (Fig. 3C). This may result from proteases present in other microorganisms whose substrate specificities are different from those of strain BLxT, because several kinds of proteolytic bacteria were isolated from the composting process (data not shown). It is also uncertain whether gelatinases (proteases) detected in the zymogram after day 16.5 were derived from strain BLxT. Proteases of other bacteria may have lower affinity for gelatin than the gelatinases from strain BLxT. The activity was almost undetectable on day 2.5, and this may have been for the same reasons. Bacteria producing proteases with higher specificity for Azocoll might have been present on day 2.5.

The N-terminal amino acid sequence of the gelatinase from strain BLxT was similar (52.6% identity) to that of the 50-kDa form of the bacillopeptidase F protein (43). The bacillopeptidase F protein is originally produced as a 92-kDa preproform. After processing at both termini, the mature forms of the protease, ranging from 50 to 80 kDa, are excreted. Active bands (35.6 to 68.9 kDa) above 23.5 kDa from the compost sample might derive from strain BLxT if this type of processing occurred on the gelatinase from strain BLxT (Fig. 4A). It is not clear whether the largest active band (above 97.2 kDa) from the compost sample was derived from strain BLxT. After phenyl-Sepharose column chromatography, the activities of partially purified gelatinases from strain BLxT with Azocoll were inhibited by phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride but not by EDTA (data not shown). Generally speaking, gelatinases require metal ions for activity (21). These results indicate that gelatinases from strain BLxT may be serine proteases rather than gelatinases (metalloproteases). However, further studies are necessary, because none of them has been purified to homogeneity.

Strain BTa seems not to be an active amylase producer.

The drastic increase in the abundance ratio of strain BTa did not accompany the increase in the amylase activity (Fig. 5). When strain BTa was present as a dominant organism, the amylase activity was much lower than expected. Furthermore, the amylase activity patterns in strain BTa and the compost samples were different. Strain BTa seems not to produce amylases during the composting process. This phenomenon may result from differences in growth environments. Sugars in the compost might be one of the factors. Synthesis of α-amylase by B. subtilis is strongly repressed if a rapidly metabolizable carbon source, such as glucose, is present in the growth medium (14). Furthermore, strain BTa is able to utilize certain kinds of sugars, e.g., d-glucose, d-fructose, and maltose (data not shown). These sugars are likely to be present in kitchen refuse (apple or banana) and may repress amylase production in strain BTa. Based on these results, strain BTa may not excrete amylases during the composting process.

Conclusion.

Traditional studies of microbial communities during the composting process have been conducted mainly with culture-dependent strategies (3, 4, 9, 10, 11, 35, 36, 37, 39). It was thought that the properties of the isolated microorganisms were functioning during the composting process (4, 11, 38, 39). Meanwhile, the properties of the microorganisms that were related to the genetic sequences obtained by the culture-independent approach were often thought to link to their functions during the process (17, 31). With only the culture-dependent approach, the existence and the functions of the rare microorganisms identified on plates (e.g., strain BLxT), which were reproducibly detected with culture-independent strategies, would not have been determined. Moreover, strain BTa, which was detected by both culture-dependent and culture-independent approaches, had amylase activity and therefore was thought to produce amylase during the composting process. However, our results indicate that the contribution of strain BTa to the initial step in the decomposition of starch was insignificant. Based on these results, we conclude that the deduced functions of microorganisms cannot be directly linked to their functions in the community, regardless of their apparent importance as determined from culture-dependent and/or culture-independent approaches. Hence, we should consider whether the deduced functions of microorganisms are really functioning on site when linking microbial community structure and function.

In this report, we focused on microorganisms that are present as major species in the community. However, the existence of minor species is not negligible. We have isolated microorganisms that had specific functions relating to the decomposition of kitchen refuse (data not shown). These microorganisms were thought to exist as minor species on the basis of culture-independent analysis. Further studies are necessary to elucidate their contributions to the composting process.

In order to link the structure of microbial communities to function, many studies have been performed with culture-independent approaches in recent years. Many of them dealt with an analysis of the diversity of functional genes and/or the detection of specific gene expression (mRNAs). However, these results may not always directly reflect those functions on site, especially in the case of mRNA expression analysis, because of the possibility of posttranscriptional modification of proteins. Nevertheless, these types of studies provide good indicators for the linkage between structure and function of microbial communities (42). In this report, we attempted to reveal a structure-function linkage of the microbial community during a composting process in relation to activity at the enzyme (protein) level. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report demonstrating that the functions of specific microorganisms are directly linked to their functions in the community during the process of decomposing solid waste.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amann, R. I., W. Ludwig, and K. H. Schleifer. 1995. Phylogenetic identification and in situ detection of individual microbial cells without cultivation. Microbiol. Rev. 59:143-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashelford, K. E., A. J. Weightman, and J. C. Fry. 2002. PRIMROSE: a computer program for generating and estimating the phylogenetic range of 16S rRNA oligonucleotide probes and primers in conjunction with the RDP-II database. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:3481-3489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beffa, T., M. Blanc, P. F. Lyon, G. Vogt, M. Marchiani, J. L. Fischer, and M. Aragno. 1996. Isolation of Thermus strains from hot composts (60 to 80°C). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:1723-1727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beffa, T., M. Blanc, L. Marilley, J. L. Fischer, P. F. Lyon, and M. Aragno. 1996. Taxonomic and metabolic microbial diversity during composting, p. 149-161. In M. de Bertoldi, P. Sequi, B. Lemmes, and T. Papi (ed.), The science of composting, part I. Chapman and Hall, London, United Kingdom.

- 5.Caraway, W. T. 1959. A stable starch substrate for the determination of amylase in serum and other body fluids. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 32:97-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chavira, R., Jr., T. J. Burnett, and J. H. Hageman. 1984. Assaying proteinases with Azocoll. Anal. Biochem. 136:446-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Combet-Blanc, Y., B. Ollivier, C. Streicher, B. K. Patel, P. P. Dwivedi, B. Pot, G. Prensier, and J. L. Garcia. 1995. Bacillus thermoamylovorans sp. nov., a moderately thermophilic and amylolytic bacterium. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 45:9-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dees, P. M., and W. C. Ghiorse. 2001. Microbial diversity in hot synthetic compost as revealed by PCR-amplified rRNA sequences from cultivated isolates and extracted DNA. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 35:207-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finstein, M. S., and M. L. Morris. 1975. Microbiology of municipal solid waste composting. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 19:113-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujio, Y., and S. Kume. 1991. Isolation and identification of thermophilic bacteria from sewage sludge compost. J. Ferment. Bioeng. 72:334-337. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hankin, L. H., R. P. Poincelot, and S. L. Anagnostakis. 1976. Microorganisms from composting leaves: ability to produce extracellular enzymes. Microb. Ecol. 2:296-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haruta, S., M. Kondo, K. Nakamura, H. Aiba, S. Ueno, M. Ishii, and Y. Igarashi. 2002. Microbial community changes during organic solid waste treatment analyzed by double gradient-denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis and fluorescence in situ hybridization. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 60:224-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hellmann, B., L. Zelles, A. Palojarvi, and Q. Bai. 1997. Emission of climate-relevant trace gases and succession of microbial communities during open-windrow composting. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:1011-1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henkin, T. M., F. J. Grundy, W. L. Nicholson, and G. H. Chambliss. 1991. Catabolite repression of alpha-amylase gene expression in Bacillus subtilis involves a trans-acting gene product homologous to the Escherichia coli lacl and galR repressors. Mol. Microbiol. 5:575-584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hiraishi, A., Y. Yamanaka, and T. Narihiro. 2000. Seasonal microbial community dynamics in a flowerpot-using personal composting system for disposal of household biowaste. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 46:133-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hiraishi, A., T. Narihiro, and Y. Yamanaka. 2003. Microbial community dynamics during start-up operation of flowerpot-using fed-batch reactors for composting of household biowaste. Environ. Microbiol. 5:765-776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ishii, K., M. Fukui, and S. Takii. 2000. Microbial succession during a composting process as evaluated by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis analysis. J. Appl. Microbiol. 89:768-777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kageyama, A., M. Sakamoto, and Y. Benno. 2000. Rapid identification and quantification of Collinsella aerofaciens using PCR. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 183:43-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kowalchuk, G. A., Z. S. Naoumenko, P. J. L. Derikx, A. Felske, J. R. Stephen, and I. A. Arkhipchenko. 1999. Molecular analysis of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria of the subdivision of the class Proteobacteria in compost and composted materials. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:396-403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kurisu, F., H. Satoh, T. Mino, and T. Matsuo. 2002. Microbial community analysis of thermophilic contact oxidation process by using ribosomal RNA approaches and the quinone profile method. Water Res. 36:429-438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Makinen, P. L., D. B. Clewell, F. An, and K. K. Makinen. 1989. Purification and substrate specificity of a strongly hydrophobic extracellular metalloendopeptidase (“gelatinase”) from Streptococcus faecalis (strain 0G1-10). J. Biol. Chem. 264:3325-3334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manefield, M., A. S. Whiteley, R. I. Griffiths, and M. J. Bailey. 2002. RNA stable isotope probing, a novel means of linking microbial community function to phylogeny. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:5367-5373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Metcalfe, A. C., M. Krsek, G. W. Gooday, J. I. Prosser, and E. M. Wellington. 2002. Molecular analysis of a bacterial chitinolytic community in an upland pasture. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:5042-5050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morikawa, M., Y. Izawa, N. Rashid, T. Hoaki, and T. Imanaka. 1994. Purification and characterization of a thermostable thiol protease from a newly isolated hyperthermophilic Pyrococcus sp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:4559-4566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muyzer, G., S. Hottentraeger, A. Teske, and C. Wawer. 1996. Denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis of PCR-amplified 16S rDNA—a new molecular approach to analyze the genetic diversity of mixed microbial communities, p. 3.4.4.1-3.4.4.23. In A. D. L. Akkermans, J. D. van Elsas, and F. J. DeBruijn (ed.), Molecular microbial ecology manual. Kluwer, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- 26.Nakamura, K., S. Haruta, S. Ueno, M. Ishii, A. Yokota, and Y. Igarashi. 2003. Cerasibacillus quisquiliarum gen. nov., sp. nov., isolated from a semi-continuous decomposing system of kitchen refuse. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Nakayama, J., Y. Cao, T. Horii, S. Sakuda, A. D. Akkermans, W. M. de Vos, and H. Nagasawa. 2001. Gelatinase biosynthesis-activating pheromone: a peptide lactone that mediates a quorum sensing in Enterococcus faecalis. Mol. Microbiol. 41:145-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Narihiro, T., Y. Yamanaka, and A. Hiraishi. 2003. High culturability of bacteria in commercially available personal composters for fed-batch treatment of household biowaste. Microbes Environ. 18:94-99. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olesena, L. D., K. M. Kragh, and M. Zimmermann. 2000. Purification and characterization of a malto-oligosaccharide-forming amylase active at high pH from Bacillus clausii BT-21. Carbohydr. Res. 329:97-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pedro, M. S., S. Haruta, M. Hazaka, R. Shimada, C. Yoshida, K. Hiura, M. Ishii, and Y. Igarashi. 2001. Denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis analyses of microbial community from field-scale composter. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 91:159-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pedro, M. S., S. Haruta, K. Nakamura, M. Hazaka, M. Ishii, and Y. Igarashi. 2003. Isolation and characterization of predominant microorganisms during decomposition of waste materials in a field-scale composter. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 95:368-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peters, S., S. Koschinsky, F. Schwieger, and C. C. Tebbe. 2000. Succession of microbial communities during hot composting as detected by PCR-single-strand-conformation polymorphism-based genetic profiles of small-subunit rRNA genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:930-936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pinhassi, J., F. Azam, J. Hemphala, R. A. Long, J. Martinez, U. L. Zweifel, and A. Hagstrom. 1999. Coupling between bacterioplankton species composition, population dynamics, and organic matter degradation. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 17:13-26. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ririe, K. M., R. P. Rasmussen, and C. T. Witter. 1997. Product differentiation by analysis of DNA melting curves during the polymerase chain reaction. Anal. Biochem. 245:154-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ryckeboer, J., J. Mergaert, J. Coosemans, K. Deprins, and J. Swings. 2003. Microbiological aspects of biowaste during composting in a monitored compost bin. J. Appl. Microbiol. 94:127-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Strom, P. F. 1985. Effect of temperature on bacterial species diversity in thermophilic solid-waste composting. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 50:899-905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strom, P. F. 1985. Identification of thermophilic bacteria in solid-waste composting. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 50:906-913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stutzenberger, F. J., A. J. Kaufman, and R. D. Lossin. 1970. Cellulolytic activity in municipal solid waste composting. Can. J. Microbiol. 16:553-560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stutzenberger, F. J. 1971. Cellulase production by Thermononospora curvata isolated from municipal solid waste compost. Appl. Microbiol. 22:147-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tiquia, S. M., J. H. C. Wan, and N. F. Y. Tam. 2002. Microbial population dynamics and enzyme activities during composting. Compost Sci. Util. 10:150-161. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Torsvik, V., and L. Ovreas. 2002. Microbial diversity and function in soil: from genes to ecosystems. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 5:240-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wellington, E. M. H., A. Berry, and M. Krsek. 2003. Resolving functional diversity in relation to microbial community structure in soil: exploiting genomics and stable isotope probing. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 6:295-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu, X. C., S. Nathoo, A. S. Pang, T. Carne, and S. L. Wong. 1990. Cloning, genetic organization, and characterization of a structural gene encoding bacillopeptidase F from Bacillus subtilis. J. Biol. Chem. 265:6845-6850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhu, H., F. Qu, and L. H. Zhu. 1993. Isolation of genomic DNAs from plants, fungi and bacteria using benzyl chloride. Nucleic Acids Res. 21:5279-5280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]