Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) is a syndrome that manifests with behavioral disturbance and cognitive decline in patients with repetitive head trauma.1 The syndrome was first described in boxers in the 1920s,2 but there are concerns that other athletes may be susceptible to this disease.3 A main driving force is the finding of unique pathologic changes, including characteristic aggregates of hyperphosphorylated tau and TDP-43, in the brains of patients with CTE.4 These pathologic changes have been reported in sports including boxing, American football, rugby, and ice hockey.3–5 Mild CTE pathologic changes have also been reported in 2 young soccer players,3,6 but there are no published reports in the scientific literature demonstrating late-stage CTE pathologic changes in a patient with significant soccer history and dementia. We describe such a case that supports the premise that CTE pathologic changes can occur in soccer players.

Case report.

Although he had always been detail-oriented, the patient became abnormally obsessed with business affairs and demonstrated poor judgment at age 70 years. He was also more irritable and anxious than previously. Neurologic examination, head CT, and EEG had normal results, and sertraline improved his mood. Symptoms progressed over 3 years with additional word-finding issues, memory loss, and disorientation. Examination demonstrated apathy, irritability, and dysnomia with mild rigidity on the right and stooped posture. Neuropsychological testing demonstrated mild deficits in language and verbal learning with intact recognition and Mini-Mental State Examination score of 27/30. Head CT remained normal, but EEG showed frontal intermittent rhythmic delta activity. Brain PET also showed subtle left frontal and temporal hypometabolism suggesting a frontotemporal dementia variant.

Medical history included prostate cancer, atrial fibrillation, gout, sleep apnea, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and depression. There was a family history of Parkinson disease. The patient's work history was significant for at least 16 years of professional soccer in the United Kingdom as forward/striker with over 300 games. It is unknown how many subconcussive head injuries or concussions he experienced from heading the ball or colliding with other players or the ground.

After 6 years of symptoms, the patient's clinical diagnosis was changed to Alzheimer disease (AD) due to continued cognitive decline and repeat brain PET with subtle temporal/parietal hypometabolism. The mild parkinsonism did not progress. He died from complications due to prostate cancer approximately 10 years after cognitive symptom onset.

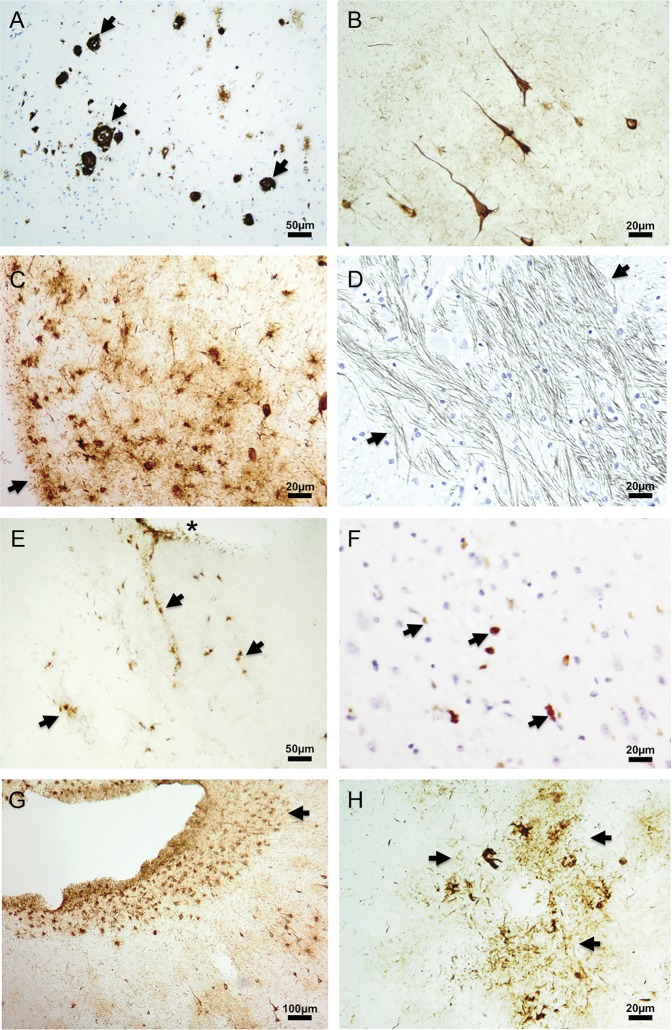

At autopsy, the brain weighed 1,320 g with mild generalized atrophy and prominent atrophy of the entorhinal cortex and hippocampus. There was marked atrophy of the mammillary bodies and pallor of the locus ceruleus and substantia nigra. CA1 of the hippocampus demonstrated gliosis. A single focus of moderate neuritic plaques was found in the temporal lobe (figure, A), but plaques were otherwise diffuse. Frequent tau-positive neurofibrillary tangles were found throughout the neocortex (figure, B) and subcortical structures. Tau-immunoreactive astrocytes were also noted throughout the neural axis (figure, C and D). Brainstem neuronal processes also demonstrated abnormal tau immunoreactivity (figure, E). TDP-43 cytoplasmic inclusions were distributed throughout the brain (figure, F).

Figure. Immunohistochemistry staining of brain sections from chronic traumatic encephalopathy case.

A 9-µm paraffin section from (A) temporal cortex with focus of β-amyloid-positive neuritic plaques (black arrows), (D) medulla with tau immunoreactivity in neuronal processes (black arrows), and (F) hippocampus with TDP-43 aggregates (black arrows). Fifty-micrometer fixed free-floating sections from (B) frontal cortex with cortical layer I–II tau-positive neurofibrillary tangles, (C) pons with tau-immunoreactive glia (black arrow pointing to pial surface), (E) spinal cord with tau immunoreactivity glia (black arrows; *central canal), (G) temporal cortex with subpial tau immunoreactivity in depth of sulcus (black arrow), and (H) frontal cortex with tau immunoreactivity surrounding a blood vessel (black arrows). Antibodies: (A) monoclonal β-amyloid 4G8, (B–C, E, G–H) monoclonal p-tau AT8, (D) monoclonal p-tau PHF1, (F) polyclonal p-TDP43. Representative sections are shown. Section sampling for the entire case (exceeding National Institute on Aging–Alzheimer's Association guidelines) included 28 sections from 8 different regions of neocortex, hippocampus, amygdala, entorhinal cortex, 2 levels of basal ganglia, hypothalamus, thalamus, midbrain, pons, medulla, cerebellum, all levels of spinal cord, and dorsal root ganglia.

Discussion.

Many characteristics support a CTE diagnosis in this case. Tau pathology distributed throughout the brain, brainstem, and spinal cord was likely the major feature contributing to the patient's syndrome, a mixture of the 2 CTE clinical variants with behavioral and cognitive symptoms.1 Amyloid pathology was present but far more limited than expected for AD dementia. Also consistent with CTE was the pattern of atrophy, pallor in the substantia nigra and locus ceruleus, and marked atrophy of the mammillary bodies.4 Other CTE characteristics included frequent tau-positive astrocytes, large superficial neurofibrillary tangles, and TDP43 aggregates. More importantly, we also observed highly characteristic sulcal (figure, G) and vascular (figure, H) deposition of tau pathology, possibly resulting from physical and shear stresses the patient's brain encountered with head injuries. Brain structural and cognitive changes have been reported in soccer players.7

Given the patient's extended tenure in the prestigious and often highly physical UK soccer leagues, we postulate that chronic head injuries sustained during play may have been a major inciting or contributing event for his clinical dementia and underlying neurodegenerative process. A recent story in the lay press reported another UK soccer player from the same era with cognitive changes and pathologic findings concerning for CTE,8 but details surrounding the pathology in this case are not yet published. These associations are further bolstered by reports of mild CTE pathologic changes in 2 young soccer players.3,6 Therefore, this case report suggests that more studies are warranted to determine the connection among soccer, CTE, neurodegeneration, and dementia.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment: The authors thank the patient and his family for donating neural tissues and the Boston University CTE Center for review of this case.

Footnotes

Author contributions: Dr. Hales: writing of manuscript, neuropathologic evaluation of the case, immunostaining and acquisition of images. Dr. Neill, Dr. Gearing, and Dr. Glass: neuropathologic evaluation of the case and critical revision of the manuscript. D. Cooper: paraffin immunostaining. Dr. Lah: clinical and neuropathologic evaluation of the case and critical revision of the manuscript.

Study funding: Supported by Emory Alzheimer's Disease Research Center-NIA-AG025688 and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke K08-NS087121.

Disclosure: The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Stern RA, Daneshvar DH, Baugh CM, et al. Clinical presentation of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Neurology 2013;81:1122–1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martland H. Punch drunk. JAMA 1928;91:1103–1107. [Google Scholar]

- 3.McKee AC, Daneshvar DH, Alvarez VE, Stein TD. The neuropathology of sport. Acta Neuropathol 2014;127:29–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKee AC, Stein TD, Nowinski CJ, et al. The spectrum of disease in chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Brain 2013;136:43–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Omalu B, Bailes J, Hamilton RL, et al. Emerging histomorphologic phenotypes of chronic traumatic encephalopathy in American athletes. Neurosurgery 2011;69:173–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geddes JF, Vowles GH, Nicoll JA, Revesz T. Neuronal cytoskeletal changes are an early consequence of repetitive head injury. Acta Neuropathol 1999;98:171–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maher ME, Hutchison M, Cusimano M, Comper P, Schweizer TA. Concussions and heading in soccer: a review of the evidence of incidence, mechanisms, biomarkers and neurocognitive outcomes. Brain Inj 2014;28:271–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.BBC News. Jeff Astle: West Brom Legend “killed by boxing brain condition.” 2014. Available at: http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-birmingham-27654892. Accessed June 4, 2014.