Abstract

Objective

To assess the impact of gestational weight gain outside the Institute of Medicine (IOM) recommendations after the diagnosis of gestational diabetes (GDM) on perinatal outcomes.

Methods

Retrospective cohort study. Women were classified as GWG within, less than, or greater than IOM recommendations for body mass index (BMI) as calculated by gestational weight gain per week after a diagnosis of GDM. Outcomes assessed were preeclampsia, cesarean delivery, A2 GDM, birth weight, small for gestational age, large for gestational age, macrosomia, and preterm delivery. Groups were compared using analysis of variance and chi-squared test for trend, as appropriate. Backwards stepwise logistic regression was used to adjust for significant confounding factors.

Results

Of 635 subjects, 92 gained within, 175 gained less than, and 368 gained more than IOM recommendations. The risk of cesarean delivery and A2 GDM was increased in those gaining above the IOM recommendations compared to within. For every 1-lb/week increase in weight gain after diagnosis of GDM, there was a 36–83% increase in the risk of preeclampsia, cesarean, A2 GDM, macrosomia, and LGA, without decreases in SGA or preterm delivery.

Conclusions

Weight gain more than the IOM recommendations per week of gestation after a diagnosis of GDM is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Introduction

Guidelines developed by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) for gestational weight gain, published in 2009, suggest a range of weight gain for the pregnancy as a whole and per week by gestational age.1 These recommendations are based on the weight gain necessary to achieve an ideal birth weight, which is directly linked to gestational weight gain. Gestational weight gain may be associated with other outcomes, such as gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, and preterm delivery, but poor quality of evidence and conflicting results make these associations difficult to interpret.2 The IOM guidelines were developed for a healthy population, and tailored recommendations for special populations, such as women with gestational diabetes, were not created. As gestational diabetes complicates 4–7% of pregnancies in the United States,3 it is imperative to evaluate these guidelines in this population.

Gestational diabetes (GDM), a carbohydrate intolerance first recognized during pregnancy,3 has been associated with excess gestational weight gain in some studies.4,5 Because obesity, weight gain and insulin resistance are tightly linked,6–8 weight gain in insulin-resistant women may exaggerate insulin resistance and worsen GDM outcomes. On the other hand, inadequate gestational weight gain is also associated with adverse perinatal outcomes such as preterm delivery and fetal growth restriction.

The impact of gestational weight gain after the diagnosis of GDM has not been thoroughly evaluated, in part because the vast majority of studies on gestational weight gain utilize birth certificate registries that only record total weight gain.9–13 However, physicians cannot accurately predict which women will develop GDM in the third trimester; women who ultimately develop GDM typically receive standard gestational weight gain counseling at an early prenatal visit and then undergo additional dietary counseling after the diagnosis of GDM. Ideally, gestational weight gain counseling specific to GDM would be available at the time of diabetic dietary counseling. Given these competing interests of gestational weight gain and insulin resistance, as well as the lack of evidence evaluating IOM recommendations in GDM, information regarding the optimal gestational weight gain after a diagnosis of GDM is needed. Therefore, we aimed to evaluate the relationship of weight gain within and outside of the IOM guidelines after a diagnosis of GDM and pregnancy outcomes (preeclampsia, cesarean delivery, use of hypoglycemic medications, preterm birth, birth weight, and birth injury) using a retrospective cohort with detailed information on pre-pregnancy weight and gestational weight gain.

Materials and Methods

We performed a retrospective cohort study of all singleton pregnancies delivered at the University of Alabama at Birmingham with a diagnosis of gestational diabetes from 2007–2012. Institutional review board approval was obtained from the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Subjects were identified by a diagnosis of gestational diabetes as listed on our obstetric database discharge forms. Standardized chart abstraction forms were used to abstract data from the medical charts by physicians in obstetrics and gynecology and a medical student trained in chart abstraction. Data collected included detailed information on maternal demographics, medical and obstetrical history, GDM screening and diagnosis results, prenatal blood sugar logs, medication use, labor and delivery events, and neonatal outcomes. At our institution, GDM screening is accomplished with a one-hour, 50-gram glucose challenge test. If the glucose challenge test is ≥135 mg/dL, women proceed to a three-hour, 100-gram glucose tolerance test. Women with a glucose challenge test ≥200 mg/dL are treated as GDM without further diagnostic testing. The Carpenter-Coustan criteria are used to diagnose GDM (at least two values must be abnormal, fasting glucose ≥95 mg/dL, 1-hour glucose ≥180 mg/dL, 2-hour glucose ≥155 mg/dL, and 3-hour glucose ≥140 mg/dL). Women with a fasting blood sugar ≥120 mg/dL were not administered a 100-g glucose load and were diagnosed with GDM. All women were managed by institutional protocol under the supervision of maternal-fetal medicine specialists. Each woman underwent individualized nutrition counseling and diabetic education upon her diagnosis of GDM. Per institution protocol, hypoglycemic medications are initiated after a trial of diet when ≥50% of blood sugars are elevated from target values of <95 mg/dL fasting and <120 mg/dL at 2 hours postprandial.

Gestational weight gain per week was calculated as: (last measured weight–weight at diagnosis) / (gestational age at delivery-gestational age at diagnosis). Women were classified as GWG within, less than or greater than IOM recommendations for pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI). Pre-preganncy body mass index was determined from self-reported height and prepregnancy weight. Per week of pregnancy in the second and third trimesters, the IOM recommendations specify that underweight women (BMI <18.5 kg/m2) should gain 1–1.3 lb/week, normal weight women (BMI 18.5–24.9 kg/m2) should gain 0.8–1 lb/week, overweight women (BMI 25.0–29.9) should gain 0.5–0.7 lb/week, and obese women (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) should gain 0.4–0.6 lb/week.

Women with a singleton gestation and confirmed diagnosis of GDM were included in the study. Women were excluded for incomplete height and weight data, last weight measured more than 2 weeks prior to delivery, diagnosis of GDM prior to 20 weeks or after 34 weeks, major maternal medical illness (systemic lupus erythematosus, renal disease, maternal cardiac disease, pregestational diabetes, sickle cell, or cystic fibrosis), first documented ultrasound >26 weeks, and fetal anomalies. Only the first pregnancy during the ascertainment period was considered.

Maternal outcomes considered were preeclampsia, cesarean delivery, and requiring hypoglycemic medications (A2 GDM). Cesarean delivery was considered as both all cesarean deliveries (primary and repeat) and as primary cesarean delivery. A2 GDM was subdivided into oral hypoglycemic medication (glyburide at our institution) and insulin use. Neonatal outcomes were birth weight, small for gestational age (SGA, <10th percentile on Alexander standard),14 large for gestational age (LGA, >90th percentile on Alexander standard), macrosomia (>4000 g), preterm delivery (<37 weeks) and birth injury. Birth injury included shoulder dystocia, as documented by the delivering physician, brachial plexus injury, and fractures.

A secondary analysis was performed analyzing the impact of gestational weight gain after GDM diagnosis as a continuous variable. The impact of each kilogram of weight gain per week after GDM diagnosis on maternal and neonatal outcomes was assessed.

The baseline characteristics of subjects gaining within, less than, or greater than the IOM recommendations were compared with descriptive and univariable statistics using analysis of covariance tests for continuous variables and χ2 tests for categorical variables as appropriate. Normal distribution of continuous variables was tested using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The incidence of outcomes across increasing gestational weight gain categories was compared using a χ2 test for trend. Backwards stepwise logistic regression was used to refine point estimates after adjusting for confounding factors. Confounding factors considered included parity, race, age, prior mode of delivery, hypertension, and tobacco use. All analyses were completed using Stata SE, version 11 (College Station, Texas).

Results

Of exactly 1,000 women identified with a potential diagnosis of gestational diabetes, 635 were included in the analysis (102 did not meet criteria for GDM diagnosis by laboratory testing, 37 had medical complications of pregnancy, 3 were delivered outside of our ascertainment dates, 31 for fetal congenital malformations, 94 had incomplete height/weight information, 18 did not have weight documented within 14 days of delivery, 43 had uncertain dating criteria, and 37 had a diagnosis of GDM prior to 20 weeks or after 34 weeks). Of these 635 women, 92 gained within the IOM recommendations, 175 less than the IOM recommendations, and 368 more than the IOM recommendations. Women gaining above the IOM recommendations were slightly younger, less likely to be married, and had higher BMI than women gaining less than or within the IOM recommendations (Table 1). Women who gained less than or within the IOM recommendations after their diagnosis of GDM were more likely to have gained less than or within the IOM recommendations before their diagnosis compared to those who gained more than the IOM recommendations after their diagnosis (Table 2).

Table 1.

Maternal Baseline Characteristics

| Gained Less than the IOM Recommendations (n=175) |

Gain Within the IOM Recommendations (n=92) |

Gained More than IOM Recommendations (n=368) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 30.0 ± 6.1 | 29.3 ± 5.7 | 28.3 ± 5.8 | <0.01 |

| Nulliparous | 42 (24.0%) | 22 (24.2%) | 118 (32.1%) | 0.09 |

| Race | 0.27 | |||

| White | 26 (15.8%) | 10 (11.9%) | 44 (12.9%) | |

| Black | 74 (44.9%) | 34 (40.5%) | 184 (54.1%) | |

| Hispanic | 60 (36.4%) | 35 (41.7%) | 98 (28.8%) | |

| Public Insurance | 127 (78.9%) | 68 (81.0%) | 292 (86.4%) | 0.09 |

| Maternal Education | 0.46 | |||

| Less than 12th Grade | 53 (33.1%) | 20 (23.8%) | 89 (26.7%) | |

| 12th Grade | 40 (25.0%) | 19 (22.6%) | 98 (29.3%) | |

| Greater than 12th Grade | 17 (10.6%) | 11 (13.1%) | 38 (11.4%) | |

| Smoking | 29 (16.5%) | 10 (10.9%) | 66 (18.1%) | 0.50 |

| Chronic Hypertension | 17 (9.8%) | 9 (9.8%) | 45 (12.2%) | 0.64 |

| Prior Cesarean | 38 (21.7%) | 18 (19.6%) | 89 (24.2%) | 0.59 |

| Gestational Weight Gain after GDM Diagnosis (kg) | 0.52 ± 2.7 | 3.4 ± 1.2 | 6.9 ± 3.5 | <0.01 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30.8 ± 8.3 | 29.9 ± 7.8 | 33.4 ± 8.6 | <0.01 |

| BMI Category | <0.01 | |||

| Underweight | 5 (2.9%) | 1 (1.1%) | 1 (0.3%) | |

| Normal Weight | 41 (23.4%) | 28 (30.4%) | 38 (10.3%) | |

| Over Weight | 40 (22.9%) | 17 (18.5%) | 78 (21.2%) | |

| Obese | 89 (50.9%) | 46 (50.0%) | 251 (68.2%) |

Data presented as mean ± standard deviation or n (%)

IOM = Institute of Medicine

Table 2.

Weight Gain Before and After Diagnosis of GDM

| Weight Gain Before Diagnosis | Weight Gain After Diagnosis | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gained Less than the IOM Recommendations (n=175) |

Gain Within the IOM Recommendations (n=92) |

Gained More than IOM Recommendations (n=368) |

|

| Gained Less than IOM Recommendations (n=262) | 79 (45.1%) | 49 (53.3%) | 134 (36.4%) |

| Gained Within IOM Recommendations (n=85) | 29 (16.6%) | 16 (17.4%) | 40 (10.9%) |

| Gained More than IOM Recommendations (n=288) | 67 (38.3%) | 27 (29.3%) | 194 (52.7%) |

p<0.01

Data presented as n (%)

IOM = Institute of Medicine

In unadjusted analyses, as gestational weight gain category increased, so did the incidence of preeclampsia (p<0.01, Table 3). However, after adjusting for significant confounding variables, the odds of preeclampsia for women gaining outside the IOM recommendations compared to within the IOM recommendations was not statistically significant (adjusted odds ratio (AOR) for less than 0.40, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.13–1.16, AOR for more than 1.39, 95% CI 0.62–3.13). A similar pattern was seen for primary cesarean deliveries (p=0.03). When all cesarean deliveries were considered, weight gain above the IOM recommendations was associated with a significantly increased odds of requiring cesarean compared to weight gain within the recommendations (AOR 1.78, 95% CI 1.02–2.84). Women gaining more than the IOM recommendations had increased odds of A2 GDM compared to women gaining within the recommendations (AOR 2.55, 95% CI 1.42–4.56). The risk of requiring insulin increased as gestational weight gain increased (p=0.04). The time to achieve blood sugar control (defined as more than half of fasting blood sugar values <95 mg/dL and more than half of 2-hour post-prandial blood sugar values <120 mg/dL) was similar between groups.

Table 3.

Maternal Outcomes by Gestational Weight Gain after Diagnosis

| Gain Less than IOM Recommendations (n=175) |

AOR (95% CI) |

Within IOM Recommendations* (n=92) |

Gain More than IOM Recommendations (n=368) |

AOR (95% CI) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preeclampsia | 8 (4.6%) | 0.40 (0.13–1.16)† | 9 (9.8%) | 64 (17.4%) | 1.39 (0.62–3.13)† | <0.01 |

| All Cesarean (Primary & Repeat) | 64 (36.6%) | 1.19 (0.65–2.19)§ | 29 (31.5%) | 167 (45.4%) | 1.78 (1.02–2.84)§ | 0.03 |

| Primary Cesarean | 29 (20.7%) | 1.35 (0.63–2.93)‖ | 12 (16.0%) | 84 (29.5%) | 1.91 (0.94–3.88)‖ | 0.03 |

| A2 GDM | 56 (32.0%) | 1.58 (0.82–3.01)‖ | 23 (25.0%) | 170 (46.2%) | 2.55 (1.42–4.56)‖ | <0.01 |

| Gestational Diabetes, Required Glyburide | 55 (31.4%) | 1.65 (0.86–3.19)‖ | 22 (23.9%) | 162 (44.0%) | 2.52 (1.39–4.56)‖ | <0.01 |

| Gestational Diabetes, Required Insulin | 3 (1.7%) | - | 2 (2.2%) | 19 (5.2%) | - | 0.04 |

| Time to Blood Sugar Control (days) | 14 (7–28) | - | 7 (7–25) | 14 (7–22) | - | 0.89 |

Data presented as n (%) or median (interquartile range)

IOM = Institute of Medicine, A2 GDM = gestational diabetes requiring any pharmacologic agent

p-value is for χ2 test for trend

Weight gain within IOM recommendations is reference

Adjusted for black race, prepregnancy BMI, and chronic hypertension

Adjusted for advanced maternal age, black race, and prior cesarean

Adjusted for prepregnancy body mass index

Adjusted analysis not performed due to continuous variable or too few outcomes

Birth weight increased as gestational weight gain after GDM diagnosis increased, although the difference was not statistically significant (Table 4). The risk of SGA was not statistically significantly different between weight gain categories. Compared to women gaining within the IOM recommendations, women gaining more than the IOM recommendations had a 2.5-fold increased odds of macrosomia or LGA, although this difference did not reach statistical significance (lower limit of the 95% CI 0.98). The risk of preterm delivery was similar between groups, as was the risk of birth injury.

Table 4.

Neonatal Outcomes by Gestational Weight Gain after Diagnosis

| Gain Less than IOM Recommendations (n=175) |

AOR (95% CI) |

Within IOM Recommendations* (n=92) |

Gain More than IOM Recommendations (n=368) |

AOR (95% CI) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birth Weight | 3268 ± 670 | - | 3308 ± 565 | 3391 ± 670 | - | 0.11 |

| Macrosomia | 18 (10.3%) | 1.46† (0.50–4.19) | 10 (10.9%) | 56 (15.2%) | 2.59† (0.98–6.84) | 0.10 |

| LGA | 20 (11.4%) | 1.28† (0.48–3.45) | 11 (12.0%) | 63 (17.1%) | 2.43† (0.99–5.97) | 0.07 |

| SGA | 16 (9.1%) | 0.94§ (0.38–2.33) | 8 (8.7%) | 27 (7.3%) | 0.70§ (0.30–1.65) | 0.45 |

| Preterm Birth | 31 (17.7%) | 0.80 (0.37–1.71)‡ | 11 (12.0%) | 61 (16.6%) | 0.53 (0.23–1.17)‡ | 0.87 |

| Birth Injury | 5 (2.9%) | - | 2 (2.2%) | 14 (3.9%) | - | 0.19 |

Data presented as n (%) or median (interquartile range)

IOM=Institute of Medicine, LGA=large for gestational age, SGA=small for gestational age

Adjusted for prior macrosomic infant, prepregnancy BMI

Adjusted for prepregnancy BMI, smoking status

Adjusted for prior preterm delivery, black race, and advanced maternal age

Adjusted analysis not performed due to continuous variable or too few outcomes

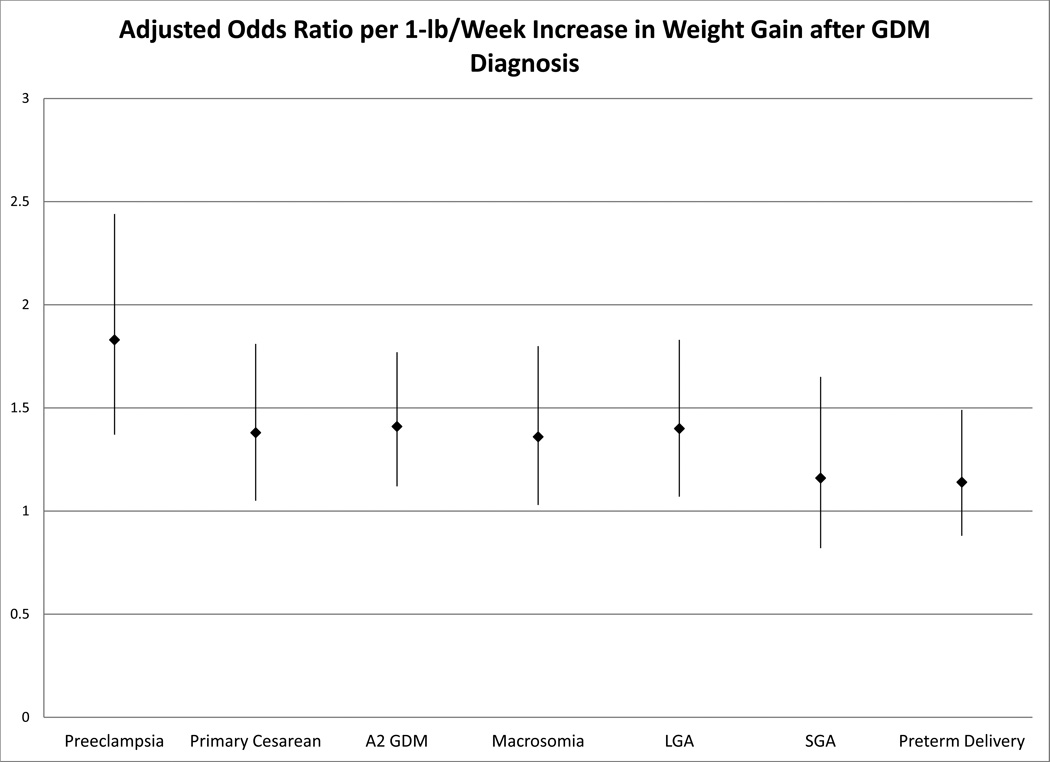

Because gestational weight gain is a continuum, and the IOM recommendations may not be applicable to GDM, the odds of several adverse outcomes (preeclampsia, primary cesarean, A2 GDM, macrosomia, LGA, SGA, and preterm delivery) were evaluated in logistic regression model with gestational weight gain per week after the diagnosis of GDM as a continuous variable (Figure 1). For every 1-lb increase in weight gain/week after a diagnosis of GDM, there was a 36–83% increase in the odds of preeclampsia, primary cesarean, A2 GDM, macrosomia, and LGA after adjusting for pre-pregnancy BMI, maternal age, and gestational weight gain per week until the diagnosis of GDM. The odds of SGA and preterm delivery were unchanged by increasing weight gain. Increasing pre-pregnancy BMI was also associated with increasing odds of preeclampsia, primary cesarean, A2 GDM, macrosomia, LGA, and preterm delivery without decreasing odds of SGA. Increasing pre-pregnancy BMI was also associated with increasing risks of preterm delivery.

Figure 1.

Adjusted odds ratio and 95% confidence interval for maternal and neonatal outcomes per kilogram of weight gain after a diagnosis of gestational diabetes. Adjusted for weight gain until the diagnosis of GDM, pre-pregnancy body mass index, and maternal age.

Discussion

After a diagnosis of GDM, gestational weight gain above the IOM recommendations was associated with increased risks of cesarean and A2 GDM compared to weight gain within the recommendations. Every 1-lb/week increase in gestational weight gain after a diagnosis of GDM is associated with increases in the odds of preeclampsia, requiring hypoglycemic medications, primary cesarean delivery, macrosomia, and LGA without decreasing the odds of SGA or preterm delivery.

Using a large California program designed for the management of diabetes in pregnancy, Cheng et al examined the impact of weight gain on outcomes in gestational diabetes.15 As they utilized a clinical program, they were able to examine the impact of weight gain before and after a diagnosis of GDM. Their results were similar to those presented here: higher weight gains after GDM diagnosis were associated with higher odds of cesarean delivery and LGA but lower odds of preterm delivery. Whereas their analysis was performed using tertiles of gestational weight gain for the cohort, we evaluated the IOM recommendations as well as gestational weight gain as a continuous variable.

Ouzounian et al performed a retrospective cohort study of diet-controlled gestational diabetes demonstrating that excess weight gain during pregnancy increased the odds of macrosomia.13 This study used total weight gain for pregnancy rather than examining the weight gain after a diagnosis of GDM. As a clinician is unable to predict whether or not a woman will develop GDM at the beginning of pregnancy, studying the impact of gestational weight gain after a GDM diagnosis is essential to developing patient guidelines for counseling once the diagnosis has been made.

The impact of gestational weight gain on pregnancy outcomes is difficult to study for many reasons. Since women cannot be randomized to a certain amount of weight gain, data must come from observational studies or studies randomizing to nutritional and exercise counseling, limiting researchers to drawing conclusions about associations rather than causation. The amount of weight gained is inherently linked to the length of the pregnancy; thus all studies must consider the length of gestation when analyzing gestational weight gain. The majority of data regarding weight gain in pregnancy comes from large, retrospective cohort studies.2 Large cohorts are typically obtained from birth certificate databases, which typically only record the total amount of weight gained for the pregnancy. Additionally, these cohorts are typically plagued by misclassification bias, biasing them towards the null.

The main strength of our study is the detailed clinical information we obtained through direct chart abstraction. All diagnoses of gestational diabetes were confirmed with a review of diagnostic testing; subjects that did not meet our institution’s diagnostic criteria were excluded from the study. Additionally, chart review confirmed detailed information such gestational age as documented by a first or second trimester ultrasound, diagnosis of preeclampsia, medications used, maternal weight and glycemic control at each prenatal visit, and neonatal outcomes. Consequently, we minimized as much as possible the typical misclassification biases present in large, vital statistics database studies. In our analysis, we considered weight gain per week rather than weight gain as a whole. This is an advantage as it inherently adjusts for the length of gestation, an important confounding factor when analyzing gestational weight gain for an entire pregnancy. Additionally, this information is more useful to clinical providers, who counsel their patients week to week regarding their weight and glycemic control. Weight gain for the entire pregnancy is less useful information for clinicians, as clinicians cannot predict weight gain for the entire pregnancy at a single visit.

The main weakness of the study is the small number of women gaining within the IOM recommendations. Although we were able to detect a trend in many outcomes across the three weight gain groups, the small number of women gaining within the IOM recommendations may have limited our power to detect a difference between this group of women and women gaining less or more than the IOM recommendations. Additionally, pre-pregnancy body mass index is an important confounding factor for many of these outcomes. While we adjusted for pre-pregnancy BMI in our analyses, ideally we would stratify all analyses by pre-pregnancy BMI. Again, we were unable to do this in our analysis due to the number of subjects in the study, particularly in the within IOM recommendations group. Finally, the time span of our study is from 2007–2012. The IOM published new guidelines for gestational weight gain in 2009. Our study time span was chosen based on changes in institutional practices in GDM management; however, the diabetic counseling patients received regarding caloric intake and carbohydrates has been unchanged since 2007. Therefore, although the IOM recommendations on gestational weight gain changed during the study period, actual patient counseling on diet did not change. Although the change in IOM recommendations could have led to a temporal change in prevalence of gestational weight gain categories, this would have had little impact on our main findings relating actual weight gain to outcomes.

Our findings suggest that weight gain after a diagnosis of GDM should be limited to the IOM recommendations, and future interventional studies should investigate whether less weight gain is appropriate in this patient population. Determining an ideal weight gain after GDM is an important component of healthy pregnancy outcomes in this patient population. A diagnosis of GDM has been demonstrated to alter gestational weight gain,16 and as these women are undergoing dietary counseling, this represents an opportunity for intervention in this high risk population.

Table 5.

Adjusted Odds of Adverse Perinatal Outcomes for Every 1-lb/week increase in Weight Gain

| Outcome | AOR (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Preeclampsia | 1.83 (1.37–2.44) |

| Primary Cesarean | 1.38 (1.05–1.81) |

| A2 GDM | 1.41 (1.12–1.77) |

| Macrosomia | 1.36 (1.03–1.80) |

| LGA | 1.40 (1.07–1.83) |

| SGA | 1.16 (0.82–1.65) |

| Preterm Delivery | 1.14 (0.88–1.49) |

Adjusted for pre-pregnancy BMI, weight gain/week until GDM diagnosis, and maternal age

Acknowledgments

Dr. Harper is supported by K12HD001258-13, PI WW Andrews, which partially supports this work.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflict of interest.

To be presented as a poster at The Pregnancy Meeting, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, February 2014.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Weight Gain During Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guidelines. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Viswanathan M, Siega-Riz AM, Moos MK, et al. Outcomes of maternal weight gain. Evidence report/technology assessment. 2008;(168):1–223. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American College of O, Gynecologists Women's Health Care P. Practice Bulletin No. 137: Gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2013;122(2 Pt 1):406–416. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000433006.09219.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carreno CA, Clifton RG, Hauth JC, et al. Excessive early gestational weight gain and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus in nulliparous women. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2012;119(6):1227–1233. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318256cf1a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hedderson MM, Gunderson EP, Ferrara A. Gestational weight gain and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2010;115(3):597–604. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181cfce4f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colditz GA, Willett WC, Rotnitzky A, Manson JE. Weight gain as a risk factor for clinical diabetes mellitus in women. Annals of internal medicine. 1995;122(7):481–486. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-7-199504010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ford ES, Williamson DF, Liu S. Weight change and diabetes incidence: findings from a national cohort of US adults. American journal of epidemiology. 1997;146(3):214–222. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu FB, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, et al. Diet, lifestyle, and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in women. The New England journal of medicine. 2001;345(11):790–797. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Egan AM, Dennedy MC, Al-Ramli W, et al. ATLANTIC-DIP: Excessive Gestational Weight Gain and Pregnancy Outcomes in Women With Gestational or Pregestational Diabetes Mellitus. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2014;99(1):212–219. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-2684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cedergren M. Effects of gestational weight gain and body mass index on obstetric outcome in Sweden. International Journal of Gynaecology & Obstetrics. 2006;93(3):269–274. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harper LM, Chang JJ, Macones GA. Adolescent Pregnancy and Weight Gain: Do the Institute of Medicine Recommendations Apply? St. Louis, MO: Washington University in St. Louis; 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kiel DW, Dodson EA, Artal R, Boehmer TK, Leet TL. Gestational weight gain and pregnancy outcomes in obese women: how much is enough? [see comment] Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2007;110(4):752–758. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000278819.17190.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ouzounian JG, Hernandez GD, Korst LM, et al. Pre-pregnancy weight and excess weight gain are risk factors for macrosomia in women with gestational diabetes. Journal of perinatology : official journal of the California Perinatal Association. 2011;31(11):717–721. doi: 10.1038/jp.2011.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alexander GR, Himes JH, Kaufman RB, Mor J, Kogan M. A United States national reference for fetal growth. Obstetrics and gynecology. 1996;87(2):163–168. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00386-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng YW, Chung JH, Kurbisch-Block I, et al. Gestational weight gain and gestational diabetes mellitus: perinatal outcomes. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2008;112(5):1015–1022. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31818b5dd9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stewart ZA, Wallace EM, Allan CA. Patterns of weight gain in pregnant women with and without gestational diabetes mellitus: an observational study. The Australian & New Zealand journal of obstetrics & gynaecology. 2012;52(5):433–439. doi: 10.1111/ajo.12001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]