Abstract

In microbial communities, bacterial populations are commonly controlled using indiscriminate, broad range antibiotics. There are few ways to target specific strains effectively without disrupting the entire microbiome and local environment. Here, we use conjugation, a natural DNA horizontal transfer process among bacterial species, to deliver an engineered CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) system for targeting specific genes in recipient Escherichia coli cells. We show that delivery of the CRISPRi system is successful and can specifically repress a reporter gene in recipient cells, thereby establishing a new tool for gene regulation across bacterial cells and potentially for bacterial population control.

Keywords: CRISPR/Cas9, synthetic biology, synthetic gene regulation, horizontal gene transfer, conjugation

The CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) system, a natural adaptive immunity system found in bacteria, has recently been repurposed as a novel method for sequence-specific gene regulation.1 A catalytically dead version of the Cas9 nuclease, dCas9, combined with a short chimeric single guide RNA (sgRNA), can bind and repress specific genes through sgRNA-mediated DNA binding. Guide RNAs are easily designed and expressed, allowing for simple yet specific gene targeting.

Natural horizontal gene transfer of CRISPR loci has been previously observed between bacterial species.2 However, it has not been repurposed for specific gene regulation using engineered target specificity. This project takes advantage of a natural horizontal gene transfer mechanism in bacteria–conjugation–to deliver an inducible CRISPRi system to repress a specific gene, mRFP, in a target Escherichia coli reporter strain. This work establishes a basic synthetic biology tool for gene regulation between bacterial species that could be elaborated for more complex manipulation of bacterial populations in future applications.

Methods and Results

Design of Conjugative CRISPRi System

For the conjugative donor, we used the E. coli strain S17-1 (ATCC). It contains chromosomal copies of genes from the natural conjugative plasmid RP4 that encode for enzymes (e.g., relaxase), structural proteins (e.g., pili formation), and other regulatory proteins necessary for conjugation.3 This allows for tighter control of conjugation as the plasmid can only be transferred by the chosen donor. We utilized a compatible 5.5 kilobase pair (kb) plasmid, pARO190 (ATCC), which contains an origin of transfer (oriT) required for conjugation from a donor to a recipient.4 All E. coli strains are competent to receive conjugative transfer, so we chose a reporter strain containing chromosomal insertions of mRFP and sfGFP to measure CRISPRi gene repression efficiency in our recipient strain.1

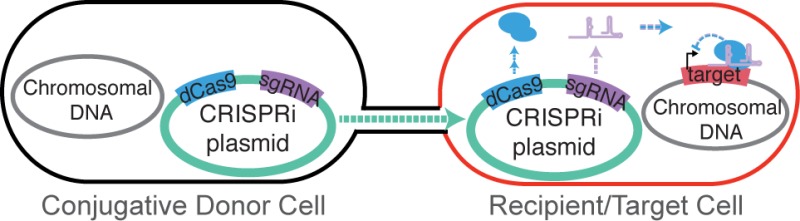

To transfer the CRISPRi system to the recipient strain, we cloned a previously described ∼100 bp chimeric sgRNA specific to mRFP and S. pyogenes dCas9 protein-coding gene into pARO190.1The sgRNA was placed under a constitutive promoter (iGEM Parts Registry BBa_J23119), while dCas9 was placed under an anhydrotetracycline (aTc)-inducible promoter (pLTetO-1)5(Figure 1B). Once conjugated into a recipient strain and induced to produce dCas9, sgRNA and dCas9 form a complex that blocks transcription of mRFP (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Design of CRISPRi Conjugative System. (A) Design of CRISPRi conjugation system. The conjugative donor strain S17–1 contains chromosomal copies of genes necessary for conjugation from natural conjugative plasmid RP4,3 and the recipient strain contains chromosomal insertions of mRFP and sfGFP.1 The conjugative plasmid encodes a CRISPRi system specifically targeting mRFP. Once the CRISPRi plasmid is conjugated from the donor into the recipient and induced to produce dCas9, sgRNA and dCas9 form a complex and block the transcription of mRFP. (B) Design of CRISPRi conjugative plasmid. The CRISPRi system was cloned into the pARO190 plasmid, which is competent for conjugative transfer by the presence of an origin of transfer (oriT).4S. pyogenes dCas9 was placed under an aTc-inducible promoter (PLtetO-1)1,5 while the sgRNA to mRFP was placed under a medium-level constitutive promoter (PON, iGEM Parts Registry BBa_J23119). Plasmid contains ampicillin/carbenicillin resistance and is approximately 10.5 kb.

Assay for Conjugative Transfer of CRISPRi System

To test for successful conjugation between E. coli strains, donor and recipient strains were grown to saturation overnight in the appropriate selective media. The cultures were washed three times by pelleting and resuspending in LB without antibiotics. The donor and recipient strains were then each diluted to OD600 0.05 in a 10 mL coculture without antibiotic selection. The cocultures were incubated at 37 °C for 8 h to allow for conjugation and then plated and selected for trans-conjugant cells (recipient strain with the conjugated plasmid) by antibiotics specific for both the recipient strain and transferred plasmid. Conjugation efficiency was estimated at 0.44% after 8 h of coculture (Table S2, Supporting Information).

Conjugated CRISPRi System Can Specifically Repress the Target mRFP Gene

Fluorescence was measured by flow cytometry to determine whether the conjugated CRISPRi system specifically repressed mRFP while leaving sfGFP unaffected in the recipient strain. After conjugation in coculture and selection for transconjugants, liquid cultures were inoculated at OD600 0.05 and dCas9 production was induced by 10 ng/μL aTc (8 h, 37 °C). Cultures were washed and resuspended in PBS and run on a LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) equipped with a high-throughput sampler.

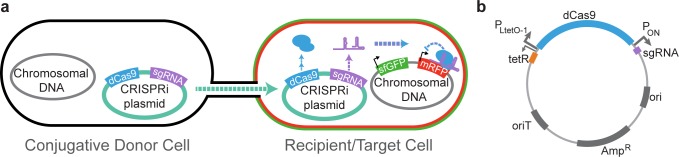

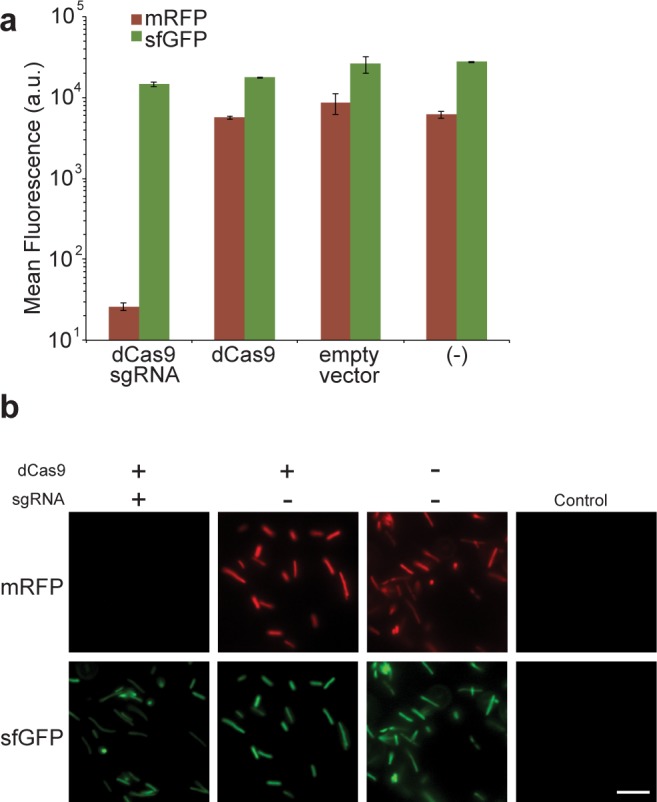

Significant repression of mRFP expression (330-fold reduction compared to that of control cells lacking the CRISPRi system) was observed when the dCas9 and a mRFP-specific sgRNA were expressed, but sfGFP expression remained high (1.2-fold reduction). Constructs expressing dCas9 alone (i.e., without the sgRNA) showed similar slight reductions in both mRFP and sfGFP expression (1.5-fold). This slight reduction correlated with dCas9 expression, potentially by contributing to metabolic burden or nonspecific targeting (Figure 2A).6 By microscopy, the cells containing the sgRNA against mRFP showed no red fluorescence, while the sfGFP signal remained high (Figure 2B). Interestingly, induction of dCas9 did not increase repression, suggesting leaky expression of the dCas9 protein that can be optimized for future applications (data not shown). Taken together, these data demonstrate the transfer of the CRISPRi system by conjugation, and that it can result in repression of a specific reporter gene in the recipient strain.

Figure 2.

Conjugated CRISPRi Causes Specific mRFP repression. (A) Specific repression of mRFP is seen only in the presence of the sgRNA complementary to mRFP, but sfGFP is not affected. Fluorescence results represent geometric mean ± s.t.d. of three biological replicates after induction by aTc. Control (−) is reporter strain without a conjugated plasmid. Flow cytometry data were analyzed by FlowJo 7.6.1. (B) Microscopic images of mRFP and sfGFP expression in target strains. Top panels are mRFP and lower panels are sfGFP. mRFP expression is selectively reduced with the presence of the sgRNA, as almost no fluorescence is observed. sfGFP expression remains high for all cells. Control shows cells with no fluorescent reporters. Scale bar, 10 μm.

Discussion

The development of engineered CRISPR/Cas systems has allowed for specific genome-editing capability by introducing DNA double-strand breaks at target sequences;7 mutants without nuclease function provide further functionality both by causing gene repression or when used as targeting domains for delivery of other transcriptional regulators.1,8 Because the CRISPR system only requires a short sequence of RNA to target nuclease binding, it provides advantages over established genome-editing systems like TALENs and zinc-finger nucleases (ZFNs) which require unique protein domains to achieve binding to the desired sequences.9 CRISPR sgRNAs are easily produced and can be multiplexed to seek out many targets with a single Cas9 adaptor,10 resulting in a gene-regulation platform of a compact size that could be transferred between cells.

Here, we demonstrate the ability to deliver a targeted gene silencing system through conjugation between E. coli strains. CRISPR systems have been shown to have highly specific recognition of particular DNA sequences and can distinguish individual strains from mixed populations of bacteria, even between highly similar strains.11 However, to our knowledge no methods of delivery of the CRISPR system to a natural mixed population of bacteria have been developed.11

The technique we describe is the first instance of cell-mediated transfer of the CRISPRi system in bacteria. Our novel design relies upon the engineering of a cell distinct from the target cell for gene knockdown, allowing for downstream manipulation of a target population of cells without direct intervention. Owing to the universality of conjugation among Gram-negative bacteria, the potential scope of targets is vast. While we have not yet demonstrated conjugative transfer in a natural microbiome, as a naturally occurring process we believe it could be optimized for therapeutic application. Alternatively, we see high potential for using bacteriophage as a delivery mechanism.12

In addition to gene regulation by CRISPRi (either by repression or activation),8 we imagine future elaborations on this system such as targeted cell killing by DNA cleavage with catalytically active Cas9,11 or even transmission of CRISPRi circuits that allow for more nuanced cellular responses.13 Combining multiple guideRNAs to multiple target sites could also provide robustness to the design not currently available with other strategies.10 This broad range of downstream effects that can be mediated by the CRISPR machinery provides a variety of powerful tools to fine tune the control of bacterial populations.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ian Ergui, Felicity Jika, Greg Fedewa, Matt Rubashkin, John Hawkins, and Suzi LeBaron, as well as the entire UCSF Center for Systems and Synthetic Biology, for helpful discussions and input. The UCSF iGEM program is the result of a unique partnership between Abraham Lincoln High School in San Francisco and the UCSF Center for Systems and Synthetic Biology, and we are grateful for their joint contributions, especially the work of key advisors Connie Lee, Hana El-Samad, George Cachianes, and Julie Reis. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health P50 GM081879, Howard Hughes Medical Institute (T.S. and W.A.L.), California Institutes for Quantitative Biosciences at UCSF, and NSF SynBERC EEC-0540879. L.S.Q. acknowledges support from the NIH Office of the Director (OD), and National Institute of Dental & Craniofacial Research (NIDCR). L.S.Q. is partly supported by NIH DP5 OD017887.

Supporting Information Available

Detailed descriptions of the materials and methods used in this study and supplementary tables. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Contributions

□ W.J., D.L., and E.W. contributed equally to this work. S.L.Q., W.A.L., and V.Z. conceived the project and assisted in design. W.J. designed and constructed the CRISPRi plasmid. W.J., D.L., E.W., P.D., D.D., V.H., K.K., and S.T. performed the experiments and conducted data analysis and interpretation. S.C., J.H., B.H., G.H., A.R., T.S., V.Z., K.J.H., and S.L.Q. assisted in project and experimental design, data analysis, and interpretation. W.J., D.L., E.W., and K.J.H. cowrote the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Qi L. S.; Larson M. H.; Gilbert L. A.; Doudna J. A.; Weissman J. S.; Arkin A. P.; Lim W. A. (2013) Repurposing CRISPR as an RNA-guided platform for sequence-specific control of gene expression. Cell 152, 1173–1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godde J. S.; Bickerton A. (2006) The repetitive DNA elements called CRISPRs and their associated genes: Evidence of horizontal transfer among prokaryotes. J. Mol. Evol. 62, 718–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon R.; Priefer U.; Pühler A. (1983) A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic-engineering—Transposon mutagenesis in Gram-negative bacteria. Bio-Technology 1, 784–791. [Google Scholar]

- Parke D. (1990) Construction of mobilizable vectors derived from plasmids Rp4, Puc18, and Puc19. Gene 93, 135–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz R.; Bujard H. (1997) Independent and tight regulation of transcriptional units in Escherichia coli via the LacR/O, the TetR/O and AraC/I1-I2 regulatory elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 1203–1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg S. H.; Redding S.; Jinek M.; Greene E. C.; Doudna J. A. (2014) DNA interrogation by the CRISPR RNA-guided endonuclease Cas9. Nature 507, 62–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sashital D. G.; Wiedenheft B.; Doudna J. A. (2012) Mechanism of foreign DNA selection in a bacterial adaptive immune system. Mol. Cell 46, 606–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert L. A.; Larson M. H.; Morsut L.; Liu Z.; Brar G. A.; Torres S. E.; Stern-Ginossar N.; Brandman O.; Whitehead E. H.; Doudna J. A.; Lim W. A.; Weissman J. S.; Qi L. S. (2013) CRISPR-mediated modular RNA-guided regulation of transcription in eukaryotes. Cell 154, 442–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaj T.; Gersbach C. A.; Barbas C. F. (2013) ZFN, TALEN, and CRISPR/Cas-based methods for genome engineering. Trends Biotechnol. 31, 397–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakuma T.; Nishikawa A.; Kume S.; Chayama K.; Yamamoto T. (2014) Multiplex genome engineering in human cells using all-in-one CRISPR/Cas9 vector system. Sci. Rep 4, 5400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomaa A. A.; Klumpe H. E.; Luo M. L.; Selle K.; Barrangou R.; Beisel C. L. (2013) Programmable removal of bacterial strains by use of genome-targeting CRISPR-Cas systems. MBio 5, e00928–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westwater C.; Schofield D. A.; Schmidt M. G.; Norris J. S.; Dolan J. W. (2002) Development of a P1 phagemid system for the delivery of DNA into Gram-negative bacteria. Microbiology (Reading, Engl.) 148, 943–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brophy J. A. N.; Voigt C. A. (2014) Principles of genetic circuit design. Nat. Methods 11, 508–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.