Abstract

In this study, we retrospectively examined the microstructural white matter integrity of children with early- and continuously-treated PKU (N = 36) in relation to multiple indices of phenylalanine (Phe) control over the lifetime. White matter integrity was assessed using mean diffusivity (MD) from diffusion tensor imaging (DTI). Eight lifetime indices of Phe control were computed to reflect average Phe (mean, index of dietary control), variability in Phe (standard deviation, standard error of estimate, % spikes), change in Phe with age (slope), and prolonged exposure to Phe (mean exposure, standard deviation exposure). Of these indices, mean Phe, mean exposure, and standard deviation exposure were the most powerful predictors of widespread microstructural white matter integrity compromise. Findings from the two previously unexamined exposure indices reflected the accumulative effects of elevations and variability in Phe. Given that prolonged exposure to elevated and variable Phe was particularly detrimental to white matter integrity, Phe should be carefully monitored and controlled throughout childhood, without liberalization of Phe control as children with PKU age.

Keywords: phenylketonuria, phenylalanine, exposure, brain, white matter, diffusion tensor imaging

1. Introduction

Phenylketonuria (PKU) is an autosomal recessive disorder characterized by disruption in the metabolism of the amino acid phenylalanine (Phe) due to a deficiency in or an absence of the phenylalanine hydroxylase (PAH) enzyme; as a result, Phe levels are elevated in individuals with PKU [1]. If untreated, PKU typically results in significant neurologic compromise and intellectual disability [2]. These severe sequelae are avoided through early detection and dietary restrictions to limit Phe intake. Nonetheless, individuals with early- and continuously-treated PKU are at risk for compromised functional outcomes such as neuropsychological impairments [3,4] psychosocial difficulties [5,6], and psychiatric disorders [7].

The brain mechanisms underlying diminution of functional outcomes are not fully understood. Previous research has largely focused on disruptions in dopamine synthesis [8,9]. However, there are also reports of increased oxidative stress [10], disrupted protein synethesis [11], and disrupted glucose metabolism [12] in individuals with PKU.

Of particular relevance to the current research, neuroimaging studies have revealed that PKU is associated with widespread compromise of the white matter of the brain. Most research has focused on white matter abnormalities that were detectable via visual inspection of structural brain images [9,13–20]. Categorical labels were then typically assigned to indicate the severity of the identified abnormalities. Although useful, this qualitative approach provides little information regarding subtle compromise in the white matter that is not obvious via visual inspection.

Recently, diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) has been used to examine the microstructural white matter integrity of individuals with PKU. This refined neuroimaging approach is sensitive to subtle white matter compromise and provides quantitative data that offer insight into the nature of white matter pathology. DTI studies have consistently shown that mean diffusivity (MD) is significantly lower across a range of brain regions in individuals with PKU in comparison with healthy controls [21–27], suggesting that the average diffusivity of water along all directions is restricted.

In terms of relationships with Phe, a number of studies have shown that greater white matter compromise (whether visible abnormalities or lower MD) is associated with higher Phe at the time of neuroimaging (i.e., concurrent Phe) or average Phe over a period of time preceding neuroimaging. It could be equally or more informative to investigate other indices of Phe control in relation to white matter compromise. However, in the only study to do so, the severity of visible white matter abnormalities was not associated with variability in Phe as measured by the standard error of estimate of Phe in relation to age (i.e., index of dietary control fluctuation) [18].

Although the studies described thus far are clearly of interest, many have been limited by the qualitative approach used to define white matter compromise. With few exceptions, white matter compromise was examined in relation to a single measurement of Phe or a single index of average Phe that was calculated over a brief period rather than over the lifetime. Some studies also suffered from small sample size or included a mixed group of individuals with PKU who were and were not on dietary Phe restriction. Finally, to our knowledge, no studies have been conducted using DTI to examine white matter integrity in relation to indices of Phe control other than concurrent Phe or average Phe over a period of time.

To address the aforementioned issues, the current study examined eight indices of Phe control over the lifetime to determine which best predicted microstructural white matter integrity in a relatively large sample of school-age children with early- and continuously-treated PKU. Two indices reflected average Phe, three indices reflected variability in Phe, and one index reflected change in Phe with age. In addition, two previously unstudied indices reflected accumulative exposure to Phe over the lifetime.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Participants

Children with PKU (n = 36; 17 male, 19 female) were recruited through metabolic clinics at Washington University in St. Louis (n = 11), Oregon Health & Science University (n = 19), the University of Missouri (n = 3), New York Medical College (n = 1), the University of Florida (n = 1), and the University of Nebraska (n = 1). All children were diagnosed with PKU soon after birth and received early treatment through dietary management to limit Phe intake. Lifetime Phe levels, with gaps of no more than 2 years prior to neuroimaging, were retrospectively available for all children. At the time of neuroimaging, age ranged from 6 to 18 years (M = 12.2, SD = 3.8), education ranged from 0 to 13 years (M = 6.4, SD = 3.8), and IQ ranged from 75 to 122 (M = 102.1, SD = 10.9). No child had a reported history of major medical, psychiatric, or learning disorder unrelated to PKU, and no child was treated with sapropterin dihydrochloride at the time of study.

2.2. Procedures

We obtained approval to conduct this study from institutional review boards for the protection of human subjects at Washington University in St. Louis, Oregon Health & Science University, and the University of Missouri, which were the sites at which DTI data were collected. All participants and/or their guardians provided written informed consent prior to engagement in study procedures. Neuroimaging data were collected as components of larger studies that included measures of cognition. Administration of all cognitive and neuroimaging procedures occurred during a single session lasting approximately 4 hours. The metabolic clinics from which children were referred provided blood Phe levels over the lifetime based on available medical records. Some of the Phe and neuroimaging data reported here have been published previously [21,28], but not in terms of relationships between various indices of Phe control and DTI findings.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Indices of Phe Control

With the exception of mean exposure and SD exposure, the indices of blood Phe control are described in detail elsewhere [28]. Briefly, we computed 8 indices over the lifetime. Average Phe was represented by mean Phe and the IDC; mean Phe was the mean of all available Phe levels, whereas the IDC was the mean of all yearly median Phe levels. Variability in Phe was reflected by the SD Phe, SEE Phe, and % spikes; SD Phe was the degree of variation in Phe around the mean; SEE Phe was the degree of variation in Phe around a regression function; % spikes was the proportion of Phe levels that were at least 600 μmol/L greater than either the preceding or succeeding Phe level in relation to the total number of Phe levels available. Change in Phe with age was represented by the slope of a regression function in which Phe was plotted in relation to age.

Finally, two previously unexamined indices of Phe control, mean exposure and SD exposure, were computed to take into account the duration (i.e., years) and accumulative effects of exposure to elevations and variability in Phe. The rationale for examining these two indices was that older children with PKU have experienced more prolonged exposure to elevations and variability in Phe than younger children. The approach used to compute the exposure indices was comparable to that used by Perantie et al. 2007 [29] to examine exposure to hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia in children with diabetes. As the first step in calculating mean exposure, we obtained the mean and standard deviation for both mean Phe and age across the entire sample of children with PKU. Z scores for mean Phe and age were then computed for each child based on the means and standard deviations of the sample. Mean exposure for each child was then calculated by summing the z scores [30] for mean Phe and age. SD exposure was similarly computed based on the mean and standard deviation for SD Phe and age across the entire sample of children with PKU. This method of calculation results in scores that approximate a normal distribution, with higher scores indicating greater exposure to Phe or variability in Phe.

2.3.2. Diffusion Tensor Imaging

Neuroimaging procedures are described in detail elsewhere [21]. Briefly, DTI data were acquired using a diffusion weighted echo planar imaging sequence along 6 (24 children) and 25 (12 children) non-collinear diffusion gradients (maximal b value of 1000 s/mm2 and voxel size 2.0 mm3) on a Siemens Tim Trio 3.0 T imaging system (Erlangen, Germany). Diffusion weighted images were registered to an in-house atlas at Washington University, and parametric maps were generated for MD. Fractional anisotropy was not examined, because previous studies have consistently found few differences between individuals with PKU and healthy controls on this DTI variable [21,22,24–27].

MD was examined using two approaches: region of interest (ROI) analyses and tract based spatial statistics (TBSS) analyses. ROI analyses focused on 10 brain regions: prefrontal cortex, centrum semiovale, posterior parietal–occipital cortex, optic radiation, hippocampus, corpus callosum (genu, body, splenium), thalamus, and putamen; data for left and right homologous brain regions were averaged. TBSS analyses were used to examine microstructural white matter integrity without regard for strict anatomical boundaries.

2.3.3. Data Analyses

For ROI analyses, z scores for MD in the 10 noted brain regions were generated for each child with PKU based on ROI data (i.e., mean and SD) previously collected in our laboratory from 62 typically–developing healthy children with an age range comparable to that of our PKU sample (details regarding the healthy sample are reported elsewhere [26]). For 5 ROIs (i.e., centrum semiovale, posterior parietal–occipital cortex, body of the corpus callosum, thalamus, putamen), there was a significant relationship between MD and age in healthy children; as such, age was statically controlled when computing MD z scores for these ROIs in children with PKU. All ROI analyses were conducted using the computed MD z scores. Because preliminary inspection of the data indicated that MD values acquired using 6 diffusion gradients were higher than MD values acquired using 25 diffusion gradients, diffusion gradient was statistically controlled in all analyses of MD z scores.

Associations between MD z scores and indices of Phe control were examined using partial Pearson correlations, with diffusion gradient entered as a control variable. Given that a number of statistical analyses were performed, statistical rigor was increased by considering findings significant only if p < .05 and effect sizes were either medium or large. Following Cohen’s convention for Pearson correlations, r = .1, r = .3, and r = .5 represented small, medium, and large effect sizes, respectively [31]. We determined whether the strength of correlations across ROIs was significantly different using a method developed by Zou [32] and modified by Baguley [33]. 95% confidence intervals (CI) were used to test for significance. If zero was not within the 95% CI, we concluded that correlations were significantly different at p < .05.

For TBSS data, regression analyses were performed to examine relationships between raw MD values and indices of Phe control. These analyses were conducted using Threshold-Free Cluster Enhancement and permutation analyses implemented in FSL (“randomize”) [34]. Because TBSS is sensitive to combining DTI images collected using different non-collinear diffusion gradients, we limited our TBSS analyses to data from the 24 children for whom 6 diffusion gradients were used. All statistically significant results were reported if p < .05 and were individually corrected using family-wise error.

3. Results

3.1. Indices of Phe Control

The total number of lifetime blood Phe levels available prior to neuroimaging evaluation across all children who participated in our study was 7,740 and ranged from 86 – 466 (M = 215.0, SD = 98.0). The range of blood Phe over the lifetime was 0 – 2,742 μmol/L. Indices of Phe control are reported in Table 1. Inspection of these data indicated that indices representing average Phe (mean Phe, IDC) exceeded the recommended range of 120 – 360 μmol/L [35–37].

Table 1.

Indices of phenylalanine (Phe) control.

| Index

|

M

|

SD

|

Range

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Average (μmol/L) | |||

| Mean Phe | 373.2 | 155.0 | 156.3 – 826.7 |

| IDC | 385.0 | 202.2 | 160.4 – 1116.3 |

| Variability (μmol/L) | |||

| SD Phe | 218.5 | 96.5 | 75.2 – 452.0 |

| SEE Phe | 204.2 | 88.2 | 75.1 – 385.2 |

| % Spikes | 2.8 | 3.1 | 0.3 – 9.4 |

| Exposure (z score) | |||

| Mean Exp | 0 | 1.8 | −2.5 – 4.5 |

| SD Exp | 0 | 1.5 | −2.1 – 4.0 |

| Change with Age (μmol/L) | |||

| Slope | 12.0 | 21.7 | −23.6 – 60.0 |

Notes: Exp = exposure; Exposure score means are zero because they are composite z scores.

As shown in Table 2, significant correlations were found among almost all indices of Phe control. Particularly robust correlations with large effect sizes were found between indices of average Phe (i.e., mean Phe, IDC, r = .95), variability in Phe (i.e., SD Phe, SEE Phe, r = .98; SD Phe, % spikes, r = .83; SEE Phe, % spikes, r = .88), and exposure to Phe (i.e., mean exposure, SD exposure, r = .92). With regard to exceptions, there were no significant correlations between change in Phe with age (i.e., slope) and either the SEE Phe or % spikes; there was also no significant correlation between % spikes and mean exposure.

Table 2.

Correlations between indices of phenylalanine (Phe) control.

| Index

|

Mean Phe

|

IDC

|

SD Phe

|

SEE Phe

|

% Spikes

|

Mean Exp

|

SD Exp

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Phe | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| IDC | .95* | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| SD Phe | .77* | .69* | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| SEE Phe | .65* | .56* | .98* | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| % Spikes | .55* | .44* | .83* | .88* | -- | -- | -- |

| Mean Exp | .87* | .87* | .49* | .37† | .27 | -- | -- |

| SD Exp | .87* | .85* | .74* | .65* | .55* | .92* | -- |

| Slope | .63* | .74* | .37† | .20 | .11 | .59* | .51* |

Notes: Exp = exposure;

p < .01,

p < .05 with medium or large effect size.

3.2. Diffusion Tensor Imaging

Raw MD values (M, SD) and MD z scores for children with PKU are reported in Table 3. In all instances, negative MD z scores indicated lower MD for children with PKU relative to the healthy control sample. In some regions (i.e., centrum semiovale, genu of the corpus callosum), MD was more than 1 standard deviation lower than that of the control sample.

Table 3.

Mean diffusivity (MD) region of interest (ROI) findings.

| ROI

|

M

|

SD

|

z

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Prefrontal | .77 | .05 | −.09 |

| Centrum Semiovale | .73 | .05 | −1.12 |

| Parietal Occipital | .78 | .06 | −.70 |

| Optic Radiation | .84 | .06 | −.24 |

| Hippocampus | .91 | .07 | −.05 |

| Genu of CC | .80 | .10 | −1.03 |

| Splenium of CC | .77 | .08 | −.46 |

| Body of CC | .89 | .15 | −.80 |

| Thalamus | .79 | .06 | −.48 |

| Putamen | .74 | .05 | −.84 |

Note: CC = corpus callosum.

3.3. Diffusion Tensor Imaging in Relation to Indices of Phe Control

Correlations between MD z scores and indices of Phe control are reported in Table 4. Mean Phe, the IDC, mean exposure, and SD exposure were significantly associated with MD z scores across the same 7 ROIs. The slope was significantly associated with MD z scores in 6 ROIs, and SD Phe was significantly related to the MD z score in 1 ROI. The IDC is not included in the table because the pattern of results was identical to that for mean Phe, both of which reflect average Phe; neither SEE Phe nor % spikes are reported because no significant correlations were found.

Table 4.

Correlations between mean diffusivity (MD) region of interest (ROI) z scores and indices of phenylalanine (Phe) control.

| ROI

|

Mean Phe

|

SD Phe

|

Mean Exp

|

SD Exp

|

Slope

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prefrontal | −.42† | −.27 | −.49* | −.49* | −.22 |

| Centrum Semiovale | −.38† | −.21 | −.41† | −.37† | −.55* |

| Parietal Occipital | −.59* | −.38† | −.64* | −.63* | −.49* |

| Optic Radiation | −.54* | −.20 | −.64* | −.54* | −.66* |

| Hippocampus | −.48* | −.10 | −.58* | −.45* | −.48* |

| Genu of CC | −.42† | −.19 | −.46* | −.40† | −.18 |

| Splenium of CC | −.42† | −.22 | −.44* | −.39† | −.46* |

| Body of CC | −.18 | −.18 | −.19 | −.22 | −.20 |

| Thalamus | −.11 | −.11 | −.11 | −.02 | −.27 |

| Putamen | −.32 | −.20 | −.23 | −.19 | −.43† |

Note: Exp = Exposure; CC = corpus callosum;

p < .01,

p < .05 with medium or large effect size.

The mean exposure and SD exposure findings were particularly intriguing because these indices of Phe control had not been examined previously. As such, we next determined whether mean exposure and SD exposure were more strongly correlated with MD z scores than mean Phe and SD Phe, respectively. In absolute terms, correlations were almost always higher for mean exposure than mean Phe and for SD exposure than SD Phe across all of the 10 ROIs examined. Formal statistical analyses, however, revealed no significant differences in the strength of correlations between MD z scores and mean Phe versus mean exposure. In contrast, correlations between MD z scores and SD exposure were significantly stronger than between MD z scores and SD Phe in 4 ROIs (prefrontal cortex [CI = .0006 – .40], posterior parietal-occipital cortex [CI = .04 – .48], optic radiation [CI = .12 – .58], hippocampus [CI = .12 – .58]); these findings indicated that the accumulative effect of prolonged exposure to variability in Phe over the lifetime was more detrimental to white matter integrity than variability in Phe on average.

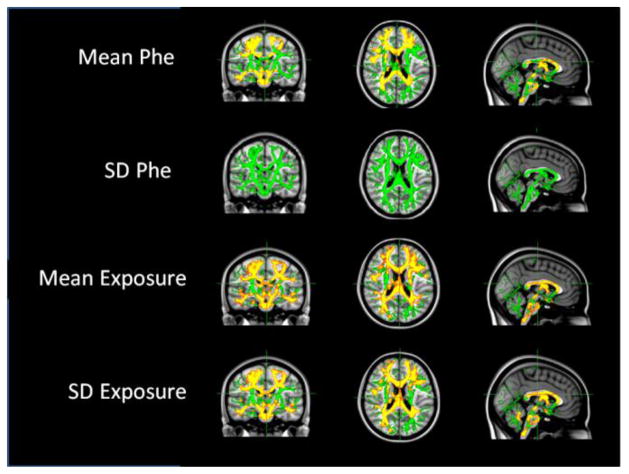

Verifying our ROI findings, as shown in Figure 1, TBSS analyses revealed significant correlations between raw MD values across a broad range of brain regions and mean Phe (as well as the IDC, not shown), mean exposure, and SD exposure. Although MD was strongly and broadly associated with SD exposure, there was no significant correlation between MD and SD Phe. There were also no significant correlations between MD and SEE Phe, % spikes, or the slope (i.e., change in Phe with age) in TBSS analyses.

Figure 1.

Relationships between mean diffusivity (MD) TBSS findings and indices of phenylalanine (Phe) control.

Notes: Green = TBSS skeleton; red = p < .01; yellow = p < .05.

4. Discussion

Our study was the first to investigate microstructural white matter integrity in relation to multiple indices of Phe control over the lifetime in children with early- and continuously-treated PKU. We assessed microstructural white matter integrity by examining MD from DTI using both ROI (over 10 brain regions) and TBSS approaches. Eight lifetime indices of Phe control were computed to reflect average Phe (mean Phe, IDC), variability in Phe (SD Phe, SEE Phe, % spikes), change in Phe with age (slope), and exposure to Phe (mean exposure, SD exposure).

With regard to our DTI findings, MD was significantly lowered across a broad range of brain regions in our sample of children with PKU. Lowered MD has also been identified in other metabolic disorders such as maple syrup urine disease and glutaric aciduria type 1 [38]. Although there has been speculation as to why MD is lowered in individuals with PKU [9], there is little evidence in support of such speculation and the precise neurobiological mechanisms are not yet fully understood.

In terms of our indices of Phe control, we found robust inter-correlations, indicating that children with higher Phe on average also had greater variability in Phe, a greater increase in Phe with age, and greater exposure to elevated and variable Phe over the lifetime. Across these indices, measures of average Phe (mean, IDC) and exposure to Phe (mean exposure, SD exposure) were most strongly related to DTI findings. Because the pattern of results for mean Phe and the IDC was identical, the remainder of this discussion will focus on mean Phe, mean exposure, and SD exposure. SD Phe will also be discussed due to contrasting findings for this variable versus SD exposure.

Correlations between DTI findings and mean Phe and mean exposure over the lifetime were not significantly different, thus providing similar information. Correlations between DTI findings and SD exposure, however, provided unique information that was not provided by SD Phe. SD exposure accounted for the prolonged and accumulative effect of exposure to variability in Phe as children with PKU aged. Considering the combined impact of variability in Phe and longer exposure to variability in Phe was crucial because SD Phe alone was largely unrelated to our DTI findings.

That is not to say that SD Phe is an unimportant index to consider. In a previous study examining cognition in relation to various indices of Phe control, we found that SD Phe was a more robust predictor of cognition (i.e., IQ and executive abilities) than mean Phe in children with PKU [28]. Although not reported in the previous study, neither mean exposure nor SD exposure were related to cognitive performance. The reasons for the incongruity between our cognitive and DTI findings in relation to indices of Phe control remain unclear, and further research is needed to elucidate possible associations between cognition and white matter compromise.

Finally, there were a number of limitations to our study. Although our sample included a relatively large number of children with PKU compared with previous studies, it is possible that additional relationships between indices of Phe control and white matter integrity would be identified in a larger sample. It is also possible that the rigorous level of statistical significance required in our study prevented us from identifying additional relationships. Nonetheless, we believe it is unlikely that our general pattern of findings would change with a larger sample or less statistical rigor. Finally, the generalizability of our findings depends upon the degree to which other cohorts of individuals with PKU are similar to the cohort included in our study.

5. Conclusion

Of the lifetime indices of Phe control examined, mean Phe, the IDC, mean exposure, and SD exposure were the most powerful predictors of widespread microstructural white matter integrity compromise in school-age children with early- and continuously-treated PKU. Given that prolonged exposure to elevated and variable Phe was particularly detrimental to white matter integrity, Phe should be carefully monitored and controlled, without liberalization of Phe control as children with PKU age.

Highlights.

Eight Phe control indices used to predict white matter integrity in children with PKU.

Prolonged exposure to elevated and variable Phe predicted poorer white matter integrity.

Low and stable Phe levels need to be maintained in children with PKU.

Phe control should not be liberalized as children with PKU age.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01HD044901), an Investigator Sponsored Trial grant from BioMarin Pharmaceutical Inc., the Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center at Washington University with funding from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (P30HD062171) and the James S. McDonnell Foundation. Drs. White, Grange, and Christ have served as consultants to and/or received research funding from BioMarin Pharmaceutical Inc. Dr. White has served as a consultant to Merck Serono S.A. The content of this article has not been influenced by these relationships. The authors wish to thank those who participated in our research for their contributions. We also thank Suzin Blankenship and Laurie Sprietsma for their contributions to study management, as well as the physicians, faculty, and staff of Washington University, Oregon Health & Science University, University of Missouri, New York Medical College, University of Florida, and University of Nebraska who generously contributed to the study through recruitment and phenylalanine monitoring.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Scriver CR. The PAH gene, phenylketonuria, and a paradigm shift. Hum Mutat. 2007;28:831–845. doi: 10.1002/humu.20526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paine RS. The variability in manifestations of untreated patients with phenylketonuria (phenylpyruvic aciduria) Pediatrics. 1957;20:290–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brumm VL, Grant ML. The role of intelligence in phenylketonuria: a review of research and management. Mol Genet Metab. 2010;99:S18–S21. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christ SE, Huijbregts SCJ, de Sonneville LMJ, White DA. Executive function in early-treated phenylketonuria: Profile and underlying mechanisms. Mol Genet Metab. 2010;99(Supple):S22–S32. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gentile JK, Ten Hoedt AE, Bosch AM. Psychosocial aspects of PKU: hidden disabilities–a review. Mol Genet Metab. 2010;99:S64–S67. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2009.10.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weglage J, Grenzebach M, Pietsch M, Feldmann R, Linnenbank R, Denecke J, et al. Behavioural and emotional problems in early-treated adolescents with phenylketonuria in comparison with diabetic patients and healthy controls. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2000;23:487–496. doi: 10.1023/a:1005664231017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brumm VL, Bilder D, Waisbren SE. Psychiatric symptoms and disorders in phenylketonuria. Mol Genet Metab. 2010;99:S59–S63. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2009.10.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leuzzi V, Bianchi MC, Tosetti M, Carducci CL, Carducci CA, Antonozzi I. Clinical significance of brain phenylalanine concentration assessed by in vivo proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy in phenylketonuria. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2000;23:563–570. doi: 10.1023/a:1005621727560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leuzzi V, Tosetti M, Montanaro D, Carducci C, Artiola C, Antonozzi I, et al. The pathogenesis of the white matter abnormalities in phenylketonuria. A multimodal 3.0 tesla MRI and magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H MRS) study. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2007;30:209–216. doi: 10.1007/s10545-006-0399-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ribas GS, Sitta A, Wajner M, Vargas CR. Oxidative stress in phenylketonuria: what is the evidence? Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2011;31:653–662. doi: 10.1007/s10571-011-9693-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoeksma M, Reijngoud DJ, Pruim J, de Valk HW, Paans AMJ, van Spronsen FJ. Phenylketonuria: high plasma phenylalanine decreases cerebral protein synthesis. Mol Genet Metab. 2009;96:177–182. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2008.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wasserstein MP, Snyderman SE, Sansaricq C, Buchsbaum MS. Cerebral glucose metabolism in adults with early treated classic phenylketonuria. Mol Genet Metab. 2006;87:272–277. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson PJ, Wood SJ, Francis DE, Coleman L, Anderson V, Boneh A. Are neuropsychological impairments in children with early-treated phenylketonuria (PKU) related to white matter abnormalities or elevated phenylalanine levels? Dev Neuropsychol. 2007;32:645–668. doi: 10.1080/87565640701375963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cleary MA, Walter JH, Wraith JE, White F, Tyler K, Jenkins JPR. Magnetic resonance imaging in phenylketonuria: reversal of cerebral white matter change. J Pediatr. 1995;127:251–255. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(95)70303-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Das AM, Goedecke K, Meyer U, Kanzelmeyer N, Koch S, Illsinger S, et al. Dietary Habits and Metabolic Control in Adolescents and Young Adults with Phenylketonuria: Self-Imposed Protein Restriction May Be Harmful. JIMD Rep. 2014:149–158. doi: 10.1007/8904_2013_273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leuzzi V, Gualdi GF, Fabbrizi F, Trasimeni G, Di Biasi C, Antonozzi I. Neuroradiological (MRI) abnormalities in phenylketonuric subjects: clinical and biochemical correlations. Neuropediatrics. 1993;24:302–306. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1071561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manara R, Burlina AP, Citton V, Ermani M, Vespignani F, Carollo C, et al. Brain MRI diffusion-weighted imaging in patients with classical phenylketonuria. Neuroradiology. 2009;51:803–812. doi: 10.1007/s00234-009-0574-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rupp A, Kreis R, Zschocke J, Slotboom J, Boesch C. Variability of blood–brain ratios of phenylalanine in typical patients with phenylketonuria. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:276–284. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200103000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scarabino T, Popolizio T, Tosetti M, Montanaro D, Giannatempo GM, Terlizzi R, et al. Phenylketonuria: white-matter changes assessed by 3.0-T magnetic resonance (MR) imaging, MR spectroscopy and MR diffusion. Radiol Med. 2009;114:461–474. doi: 10.1007/s11547-009-0365-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thompson AJ, Tillotson S, Smith I, Kendall B, Moore SG, Brenton DP. Brain MRI changes in phenylketonuria: associations with dietary status. Brain. 1993;116:811–821. doi: 10.1093/brain/116.4.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Antenor-Dorsey JAV, Hershey T, Rutlin J, Shimony JS, McKinstry RC, Grange DK, et al. White matter integrity and executive abilities in individuals with phenylketonuria. Mol Genet Metab. 2013;109:125–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2013.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ding X, Fiehler J, Kohlschütter B, Wittkugel O, Grzyska U, Zeumer H, et al. MRI abnormalities in normal-appearing brain tissue of treated adult PKU patients. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;27:998–1004. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kono K, Okano Y, Nakayama K, Hase Y, Minamikawa S, Ozawa N, et al. Diffusion-weighted MR Imaging in Patients with Phenylketonuria: Relationship between Serum Phenylalanine Levels and ADC Values in Cerebral White Matter1. Radiology. 2005;236:630–636. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2362040611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peng H, Peck D, White DA, Christ SE. Tract-based evaluation of white matter damage in individuals with early-treated phenylketonuria. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2014;37:237–243. doi: 10.1007/s10545-013-9650-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vermathen P, Robert-Tissot L, Pietz J, Lutz T, Boesch C, Kreis R. Characterization of white matter alterations in phenylketonuria by magnetic resonance relaxometry and diffusion tensor imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2007;58:1145–1156. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.White DA, Connor LT, Nardos B, Shimony JS, Archer R, Snyder AZ, et al. Age-related decline in the microstructural integrity of white matter in children with early- and continuously-treated PKU: A DTI study of the corpus callosum. Mol Genet Metab. 2010;99(Supple):S41–S46. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2009.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.White DA, Antenor-Dorsey JAV, Grange DK, Hershey T, Rutlin J, Shimony JS, et al. White matter integrity and executive abilities following treatment with tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) in individuals with phenylketonuria. Mol Genet Metab. 2013;110:213–217. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2013.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hood A, Grange DK, Christ SE, Steiner R, White DA. Variability in Phenylalanine Control Predicts IQ and Executive Abilities in Children with Phenylketonuria. Mol Genet Metab. 2014;111:445–451. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2014.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perantie DC, Wu J, Koller JM, Lim A, Warren SL, Black KJ, et al. Regional brain volume differences associated with hyperglycemia and severe hypoglycemia in youth with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:2331–2337. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reilly LC, Ciesla JA, Felton JW, Weitlauf AS, Anderson NL. Cognitive vulnerability to depression: A comparison of the weakest link, keystone and additive models. Cogn Emot. 2012;26:521–533. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2011.595776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zou GY. Toward using confidence intervals to compare correlations. Psychol Methods. 2007;12:399. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.4.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baguley T. Serious stats: A guide to advanced statistics for the behavioral sciences. Palgrave Macmillan; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nichols TE, Holmes AP. Nonparametric permutation tests for functional neuroimaging: a primer with examples. Hum Brain Mapp. 2002;15:1–25. doi: 10.1002/hbm.1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.National Institute of Health. Consensus Development Panel. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement: phenylketonuria screening and management, October 16–18, 2000. Pediatrics. 2001;108:972–982. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.4.972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Camp KM, Parisi MA, Acosta PB, Berry GT, Bilder DA, Blau N, et al. Phenylketonuria Scientific Review Conference: State of the science and future research needs. Mol Genet Metab. 2014;112:87–122. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2014.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vockley J, Andersson HC, Antshel KM, Braverman NE, Burton BK, Frazier DM, et al. Phenylalanine hydroxylase deficiency: diagnosis and management guideline. Genet Med. 2013;16:188–200. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Citton V, Burlina A, Baracchini C, Gallucci M, Catalucci A, Dal Pos S, et al. Apparent diffusion coefficient restriction in the white matter: going beyond acute brain territorial ischemia. Insights Imaging. 2012;3:155–164. doi: 10.1007/s13244-011-0114-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]