Abstract

The current paper presents novel methods for collecting MISC data and accurately assessing reliability of behavior codes at the level of the utterance. The MISC 2.1 was used to rate MI interviews from five randomized trials targeting alcohol and drug use. Sessions were coded at the utterance-level. Utterance-based coding reliability was estimated using three methods and compared to traditional reliability estimates of session tallies. Session-level reliability was generally higher compared to reliability using utterance-based codes, suggesting that typical methods for MISC reliability may be biased. These novel methods in MI fidelity data collection and reliability assessment provided rich data for therapist feedback and further analyses. Beyond implications for fidelity coding, utterance-level coding schemes may elucidate important elements in the counselor-client interaction that could inform theories of change and the practice of MI.

Keywords: motivational interviewing, MISC, inter-rater reliability, fidelity assessment

1. Introduction

Motivational Interviewing (MI) is a client-centered, collaborative style of counseling that attends to the language of change and is designed to strengthen personal motivation for and commitment to a specific goal (Miller & Rollnick, 2013). MI was originally developed to help clients prepare for changing addictive behaviors like drug and alcohol abuse (Miller & Rollnick, 1991, 2002) but has been shown to be effective across many populations for harmful behaviors including tobacco, drugs, alcohol, gambling, treatment engagement, and for promoting health behaviors such as exercise, diet, and safe sex (Lundahl, Kunz, Brownell, Tollefson, & Burke, 2010). As the basic efficacy and effectiveness of MI has been established, research has increasingly focused on how MI works (Magill et al., 2014) and how to practically measure MI counselor fidelity in real-world settings. Such research has typically used behavioral coding of MI sessions with fidelity assessment systems like the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity (MITI) (Moyers, Martin, Manuel, Miller, & Ernst, 2010) and Motivational Interviewing Skills Code (MISC; Miller, Moyers, Ernst, & Amrhein, 2008). The MITI and MISC were designed to assess MI fidelity by independent raters (coders) identifying both relational and behavioral features of therapy sessions. Each utterance (i.e., complete thought) spoken by the counselor and client during the MI interview is assigned a behavioral code. Client behavioral codes include statements in favor of changing a problem behavior like expressing reasons for or commitment to change and are referred to as “change talk.” Counselor behavioral codes also include speech patterns like open and closed questions and counseling techniques like reframing.

Research using these coding systems has explored hypothesized relationships between counselor and client speech, and between client speech and behavior change. Some research has shown that when counselors demonstrate high MI fidelity, clients are more likely to increase change talk and reduce statements away from change, called sustain talk (Moyers et al., 2007). The frequencies of client change and sustain talk, the type of change talk (e.g., commitment language) (Amrhein, Miller, Yahne, Palmer, & Fulcher, 2003; Baer, Beadnell, Garrett, Hartzler, Wells, Peterson, 2008), and where the change talk occurs in the session (Amrhein et al., 2003; Bertholet, Faouszi, Smel, Gaume, Daeppen, 2010) have been shown to independently predict behavior outcomes (Moyers et al., 2007). For example, commitment language such as, “I am going to stop drinking,” at the end of a session predicts associated behavior change (Amrhein et al., 2003), even after accounting for severity of dependence, readiness and efficacy for change (Moyers, Martin, Houck, Christopher, & Tonigan, 2009). Other research has shown that the relationship between change talk and behavior change is highly dependent on context, such as the presence of therapist MI consistent behaviors (Catley et al., 2006; Gaume, Gmel, Faouzi & Daeppen, 2008). One study suggested that change talk was only predictive of behavior change when the MI session included a personalized feedback report (Vader et al., 2010). Other studies have found relationships between some but not all subtypes of client change talk and behavior change (e.g., Gaume, Gmel, Daeppen, 2008).

Although coding systems like the MISC and MITI have become the standard for assessing MI counselor fidelity, there are challenges in how this coding data is typically collected that have implications for establishing reliability. Critically, behavioral codes are assigned to individual utterances, but data are typically collected or reported as the number of times a code was assigned across the entire session (i.e., a summary score). When the reliability of counselor and client behavior codes is assessed using summary scores, the true reliability of utterance-based codes is unclear. It is possible that coders had a similar total count of codes per session, but may have assigned different codes to the individual utterances. This distortion of reliability has implications for the accurate assessment of MI counselors and for analyses about the relationship between counselor and client speech.

The current paper presents novel methods for collecting MISC data and assessing reliability of behavior codes. It represents initial work of an interdisciplinary team of researchers applying quantitative linguistic tools such as speech signal processing (Narayanan & Georgiou, 2013) and text mining to MI and the MISC and MITI (Can, Georgiou, Atkins, & Narayanan, 2012). Prior to presenting the current research, we review the process and challenges associated with implementing the MISC.

1.1 MISC Data Collection and its Mismatch with Reliability Assessments

The first step in assessing MI fidelity using the MISC is training a team of independent raters (coders) to utilize the coding system. The most commonly reported training method is a graded process wherein coders begin by parsing (i.e., deciding where an utterance begins and ends) and assigning behavioral codes to utterances in transcripts of MI sessions with an expert rater. The expert rater is someone who has had prior experience training MI coding teams and is a member of the Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers (MINT) (Campbell, Adamson, & Carter, 2010; Gaume, Gmel, Faouzi, & Daeppen, 2008; Miller et al., 2008; Moyers, Martin, Catley, Harris, & Ahluwalia, 2003; Moyers, Miller, & Hendrickson, 2005).

To establish inter-rater reliability the coding team must reach agreement on what represents the beginning and ending of a complete thought or utterance (i.e., parsing reliability), and they must also reach agreement on what MI behavior code fits each utterance (i.e., behavior code reliability). Low parsing reliability can ultimately decrease the reliability of behavioral codes when the number of utterances, and thus number of codes, do not agree between raters. To reduce differences in coder parsing, studies have used expert raters or a separate coding team to pre-parse session transcripts (Barnett et al., 2012; Moyers & Martin, 2006; Moyers et al., 2003). Pre-parsing means that the boundaries of each thought unit or utterance are identified by one set of raters before a behavior code is assigned to the utterance by the coding team. This is the method of parsing employed in the MI-SCOPE (Martin, Moyers, Houck, Christopher & Miller, 2005). Recent software developments also facilitate parsing sessions prior to coding (Glynn, Hallgren, Houck, & Moyers, 2012).

While pre-parsing has been utilized in recent research to increase reliability by separating the task of parsing from coding through different coding teams (i.e., one team parses while another conducts behavior coding), the MISC manual does not mention or recommend pre-parsing (Miller et al., 2008). Ideally one coding team should be trained to parsing and behavioral coding reliability such that the same coders can consistently identify the boundaries of an utterance and label it with the appropriate code.

To assess coder reliability, the majority of studies use intraclass correlations (ICC) (Shrout & Fleiss, 1979) and Cicchetti’s (1994) standards of agreement (i.e., below .40 = poor, .40–.59 = fair, .60–.74 = good, and .75–1.00 = excellent). Behavior code agreement varies notably across trials that use recent versions of the MISC (2.0 – 2.5) and most studies do not report ICCs for individual code agreement (Boardman, Catley, Grobe, Little, & Ahluwalia, 2006; Campbell et al., 2010; Catley et al., 2006; de Jonge, Schippers, & Schaap, 2005; Martin, Christopher, Houck, & Moyers, 2011). When ICCs for individual behavior codes are reported, many important codes, such as client change talk (represented by codes ending with a +) or sustain talk (represented by codes ending with a -), may not be reliably distinguished at a good to excellent level (see Table 1). This is even the case for studies that utilize utterance-level coding schemes, like the MI-SCOPE (e.g., Moyers, Martin, Christopher, Houck, Tonigan and Amrhein, 2007).

Table 1.

Comparison of MISC coding studies’ counselor and client behavior code interrater reliability measured with intraclass correlations (ICCs)

| Counselor Codes

|

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MICO

|

MIIN

|

|||||||||||||

| Study |

n of double- coded sessions (% of total N) |

Composite (Session level) |

Open Questions |

Affirm | Total Reflections1 |

ADP | EC | Composite (Session level) |

Closed Questions |

ADW | CO | DI | RCW | Warn |

| Gaume et al., 2008a, 2008b2 | 97 (100) | .83 | .82 | .75 | .56–.60 | .66 | .75 | .31 | .65 | .48 | .22 | - | .75 | .37 |

| Cately et al., 2006 | 50 (58) | .81 | .55 | .38 | .24–.82 | −.04 | 1.00 | .51 | - | .03 | .00 | .57 | .21 | .37 |

| Boardman, Catley, Little, & Ahluwaila, 2006 | 46 (100) | - | .74 | .93 | .51–.76 | .43 | .21 | Low3 | Low | .67 | Low | .00 | .00 | Low |

| Martin, Christopher , Houck, &Moyers, 2011; Moyers 20094 | 40 (34) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| de Jonge, Schippers, & Schaap, 2005 | 39 (100) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Gaume, Bertholet, Faouszi, Gmel, Daeppen, 2012 | 31 (20) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Lord et al., 20145 | 31 (21) | - | .94 | .82 | - | .08 | .03 | - | .89 | .75 | .30 | 1 | .28 | .48 |

| Vader et al., 2010 | 16 (26.7 ) | .96 | .92 | - | .92 | - | - | .07 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Campbell et al., 2010 | 12 (11) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Client Codes

|

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reason

|

Other

|

Ability

|

Need

|

Desire

|

Taking steps |

Commit

|

||||||||||||

| Study | Session Level |

Sustain Talk |

Change Talk |

+ | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | FN |

| Gaume et al., 2008a, 2008b2 | - | - | - | .75* | .75* | - | - | .57* | .57* | .62* | .62* | .38* | .38* | .45* | .45* | .70* | .70* | .71 |

| Cately et al., 2006 | - | .53 | .78 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Boardman, Catley, Little, & Ahluwaila, 2006 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Martin, Christophe r, Houck, & Moyers, 2011; Moyers 20094 | - | - | - | - | - | - | .23 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | .62 | - | - |

| de Jonge, Schippers, & Schaap, 2005 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Gaume, Bertholet, Faouszi, Gmel, Daeppen, 2012 | .49 | .82 | .76 | .67 | .78 | .43 | .59 | .00 | -.03 | .00 | -.05 | - | .70 | .49 | -.05 | .30 | .70 | .73 |

| Lord et al., 20145 | - | - | - | .67 | .49 | .36 | .69 | .28 | .37 | .40 | .34 | .67 | .79 | .36 | .10 | .44 | .78 | .73 |

| Vader et al., 2010 | .70 | .84 | .87 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Campbell et al., 2010 | .84 | .75 | .80 | .78* | .78* | - | - | .50* | .50* | - | - | - | - | .60* | .60* | .63* | .63* | - |

Note. Studies are presented in order of sample size used to calculate interrater reliability. - Indicates not reported;

Indicates the average of sustain and change talk ICCs (e.g., Reasons to change and not to change; R+ and R-); ADP indicates Advice with Permission; EC indicates Emphasize Control; ADW indicates Advice without Permission; CO indicates Confront; DI indicates Direct; RCW indicates Raise Concern Without Permission.

Older versions of the MISC included sub-categories of Reflections including Repeat, Rephrase, Paraphrase, and Summarize.

These studies used ICCs with absolute agreement.

Behavior occurred at too low a frequency to calculate.

This study only provided a range of .56–.87 of reliability and did not specify the coding categories.

Current study.

Challenges related to assessing the reliability of MI coding systems are not new; however, there has been limited discussion in the literature about the fundamental mismatch between the process of assigning of codes to individual utterances and the assessment and reporting of reliability using summary ratings for the entire session. It is not clear whether ICCs that are based on session totals accurately reflect the true reliability of the utterance-based codes. The problem with low reliability for important behavioral codes is that much about what we can learn about how MI works hinges on the accurate identification of potential key ingredients for behavior change, like change talk. Furthermore, feedback to MI clinicians hinges on accurate fidelity assessment; if coding reliability is distorted it is difficult to gauge the level of clinical skill and provide appropriate feedback.

1.2 The Current Study

The present paper examines the preceding questions about how to collect MISC data and accurately assess its reliability. The primary aim was to compare the utterance-based reliability of MISC behavioral codes to traditional reliability based on summaries of an entire session. A team of raters coded transcripts of counselor-client MI sessions using the MISC by deciding on where each complete thought begins and ends (i.e., parsing the transcript) while exhaustively assigning MISC behavior codes to every utterance. Several different approaches were used to calculate utterance-based reliability given variations in parsing across the coding team and the approaches were compared to session-level assessments of reliability.

2. Methods

2.1. Study sample and setting

The present study drew from a collection of 985 MI-based audio-recorded therapy sessions from five different trials aimed at reducing drug and alcohol abuse (Krupski et al., 2012; Lee, Kilmer, et al., 2013; Lee, Neighbors, et al., 2014; Neighbors et al., 2012; Tollison et al., 2008). All studies were based in Seattle, Washington and all original trial methods were approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board prior to initiation. Four studies targeted either alcohol or marijuana abuse in college-aged students. The fifth study recruited from community primary care clinics where many of the clients were polysubstance users, sometimes concurrently abusing up to 5 or more types of drugs (Krupski et al., 2012). Approximately 15% (n = 155) of sessions were randomly selected for coding, and 148 were selected for final analyses after some session recordings were excluded due to recording or transcription error. Approximately 20% of sessions (n = 31) were selected for assessment of inter-rater reliability, where 63% (n = 19) included patients that reported abusing more than one substance.

2.2 MISC Coding

Two trainers, who are part of the Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers (MINT) with prior experience training coding teams, trained three undergraduate and post-baccalaureate students in coding using MI consistent training methods. The student-coders were not counselors and had no prior training in MI or counseling. The MISC Version 2.1 (Miller et al., 2008) was used for behavioral coding and the MITI 3.1.1 was used for global ratings (Moyers et al., 2010). Several modifications were made to traditional MISC coding. First, the MISC 2.1 manual recommends coding volleys (i.e., an uninterrupted sequence of utterances by the same speaker) by collapsing the repeated codes across the volley rather than retaining repeated codes at the utterance-level (e.g., a series of utterances coded Follow/Neutral (FN)/FN/FN/FN/FN/Commitment+ would be traditionally given the volley code FN/C+). Because we were striving to accurately classify each utterance, we modified the traditional MISC volley coding, and rather each utterance was assigned a code, even when the codes were the same in a series of utterances.

We also modified the MISC by adding target behavior labels to each instance of change or sustain talk in a given transcript (e.g., Need+Alcohol or Ability-Marijuana). The team created a numbered list of common target behaviors, such as marijuana or alcohol abuse, and included an “Other Drug” write-in category. If a change or sustain statement applied to multiple target behaviors, we employed stacked coding. For example, if a client that was using marijuana, opiates and alcohol said, “I am quitting everything today,” the coders might assign the following stacked codes to the utterance: Commitment+ Alcohol, Commitment+ Marijuana and Commitment+ Opiates. In stacked target behavior coding, the direction of change could be different for each target behavior in a given statement (e.g., “I could cut down on oxycodone by using marijuana for pain instead” might be assigned the codes: Reason+ Ability, Opiate and Reason- Marijuana). Despite allowances for stacked and multiple coding of change and sustain talk, the criteria for these statements remained consistent with the MISC 2.1 manual; vague statements that might not meet criteria for change talk (e.g., “I just want to be a better all around person”) were not coded as such. The purpose of this modification was to evaluate the feasibility of coding multiple specific target behaviors in interviews with polysubstance abuse; however, we did not report outcomes for this secondary aim in the present paper due to challenges assessing reliability (see Supplementary Appendix for additional discussion and detailed methods).

Eleven session recordings were used to train coders. The initial training time included hour-long meetings and coding homework spread over 5 weeks; however, after completion of training, due to lack of transcribed primary study data to begin coding, the practice and training period was artificially extended to 9 weeks. The 5 to 9 week training time range was comparable to other reported studies in the literature (e.g., de Jonge, Schippers & Schapp, 2005; Moyers & Martin, 2006). After training was completed, the team established initial inter-rater reliability by triple-coding 12 MI sessions (average session length was 28 minutes) from the 5 studies. Initial reliability was calculated using intraclass correlations (ICCs). Coders obtained at or above 0.50 agreement on most individual codes (72%) and 34% of codes were at or above 0.75. Though few studies report initial reliability for individual codes, this is consistent or better than previous reported studies initial agreement for omnibus and global ratings (e.g., Cambell, Adamson & Carter, 2010; de Jonge, Schippers and Schaap, 2005; Moyers, Martin, Catley, Harris and Aluwahlia, 2003) and was better than most studies final inter-rater reliability for individual codes (see Table 1).

After initial reliability was attained, the coding team was given a randomized list of recordings that was stratified by study in blocks of 5 to 7 sessions; the coders were assigned to code one block per week (approximately 1 to 2 recordings per day). The average length of session material coded per week was 300 minutes. Stratifying the blocks by study ensured that any drift in coding reliability would evenly affect the sample across studies.

As noted earlier most research studies using the MISC collect data in summary totals for each session; however, this method prevents reliability and other analysis based on utterances. To collect MISC data on a per-utterance basis, we modified an open-source software package called Transcriber that was originally designed for segmenting, labeling and transcribing speech (Barras, Geoffrois, Wu, & Liberman, 2001; Boudahmane, Manta, Antoine, Galliano, Barras, 1998). We aligned session transcripts with the corresponding audio recording in Transcriber. Our primary modification to this software was utilizing it for coding by adding a panel to easily parse and insert behavior codes. MI session recordings were transcribed based on guidelines developed by the engineering members of the research team, which can be provided upon request to the authors (Marin, Can, & Georgiou, 2013). We did not want the transcriptionists to contribute to pre-parsing or coding (e.g., a question mark would cue a coder that an utterance was a question); therefore, all punctuation except for hyphens and apostrophes was removed from the transcript prior to coding.

2.3 Statistical analyses

In our study the transcripts were not pre-parsed. Instead we trained coders to parsing and coding reliability following the recommendations in the MISC 2.1 manual. One goal of the overarching project is to produce data that accurately reflects the human coding process. In a real-world setting (e.g., coding a session in real time) pre-parsing a session would not be possible. Thus, it was additionally important not to pre-parse in order to preserve individual coder parsing and the decision making process as to what the bounds of a complete utterance were given the context of the interview. Though we trained the coders to agreement on parsing they did not reach 100% agreement, as is the case for all studies that do not modify the MISC protocol by pre-parsing transcripts. Because parsing varied somewhat by coder, we explored three methods for accurately calculating reliability without pre-parsing the transcript. Each method varied in its treatment of unit of analysis (words versus utterances) when the boundaries of units did not match between coders.

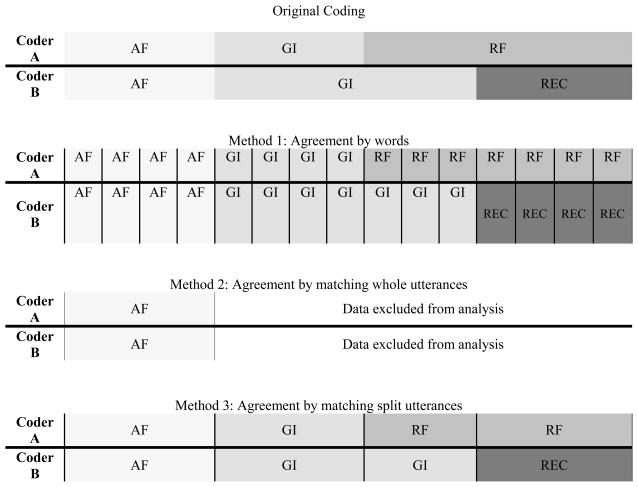

Method 1: Agreement by words

Parsing utterances can lead to disagreements about where an utterance begins and ends; however, there is no ambiguity at the level of individual words. In this method, each word within an utterance was assigned the code of the utterance in which it was contained. Reliability was assessed based on words as the unit of interest, which allowed reliability comparisons to be based on all available data (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Three different methods for assessing inter-rater reliability of utterance-level coding with varied parsing.

Note. AF = Affirmation; GI = Giving information; RF = Reframe; REC = Complex Reflection.

Method 2: Agreement by matching whole utterances

An alternative method is to consider reliability of coding based only on utterances in which coders agree on the parsing. In Method 2, all utterances where coders have boundary disagreements were excluded prior to estimating reliability. By excluding some data, this approach may be overly optimistic in calculating agreement.

Method 3: Agreement by matching split utterances

As shown in Figure 1, a compromise between the previous two methods is to retain as much utterance-based coded material as possible by splitting coded utterances into matching pairs (i.e., aligning the units of speech for each coder). Where two coders disagree on utterance boundaries, a new utterance is generated that allows the resulting utterances to be aligned. More data is included than in the previous method, though there is some inflation of agreement in terms of number of items to be compared.

Method 4: Session-level ICC reliability

The previous three methods of calculating utterance-level reliability were compared to the fourth, traditional method of calculating ICCs based on code totals for an entire session. Comparing ICCs based on code totals to Kappa statistics based on utterances should provide an estimate of the potential error in estimating reliability of coded utterances based on session totals.

For the first three methods, we assessed the reliability between a pair of coders using Cohen’s Kappa, which adjusts simple agreement for chance agreement: κ = (Po − Pe) / (1 − Pe) where Po is the observed proportion of items on which the coders agree and Pe is the proportion of items on which the coders are expected to agree under random code assignment. We obtained a summary measure for a group of three or more coders using a multi-κ measure, which took the average of Po and Pe over all coder pairs and then computed κ as normal. ICCs are an alternative form of reliability index that is appropriate for ratings on (approximately) continuous scalings. There are several versions of ICCs, depending on the nature of items and raters and the intended purpose of the ratings (Shrout & Fleiss, 1979). Present analyses used the single measure, ICC (2,1) method in which all raters rate all codes and raters are assumed to be a random sample.

After initial reliability was established 148 sessions were coded from the 5 studies. The total amount of recorded material coded was just over 58 hours (average session length was 41 minutes with a range of 6 to 82 minutes). To assess inter-rater reliability and coding drift, all 3 coders rated 21% (n = 31) of these sessions. To assess intra-rater reliability and coding drift, 17% (n = 26) of the sessions were coded by the same coder twice at different time points with a range of 2 to 6 months between re-coding; at the end of the trial we also assessed intra-rater drift over the course of one week.

3. Results

Across the 148 sessions and 3 raters, over 175,000 utterances were coded. Because we utilized utterance level coding and did not use volley coding, we were able to attain an accurate ratio of Change and Sustain Talk utterances (n = 7,157 and 6,761 respectively) to Follow/Neutral utterances n = 65,332) in client speech.

3.1 Counselor and Client Code Reliability

Total utterance-level behavioral code reliability (i.e., not distinguishing between codes) was high across the three different methods (Table 2). With all three methods, coders were observed to have “good” reliability according to Cicchetti’s (1994) guidelines, and there was a relatively small amount of variation between pairs in terms of reliability scores. The agreement “by words” method provided the smallest Kappa values and the “matching whole utterances” the largest Kappa values; the “matching split utterances” resulted in values in between the two other approaches. The multi-κ value was close to the average of the three pairwise values in all three cases. Intra-rater reliability (within rater agreement) was higher on average than inter-rater reliability (across coder agreement), but not markedly so (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Inter- and intra-rater reliability calculated with Cohen’s Kappa.

| Coder comparison | Agreement by words | Agreement by matching whole utterances | Agreement by matching split utterances | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| κ | N words | κ | N utterances | κ | N utterances | |

| A vs. B | .699 | 222539 | .770 | 16249 | .714 | 16837 |

| A vs. C | .715 | 222035 | .783 | 16770 | .722 | 17181 |

| B vs. C | .687 | 221395 | .760 | 16404 | .705 | 16842 |

| Multi-κ | .700 | .771 | .714 | |||

|

| ||||||

| A Intra- | .829 | 67866 | .865 | 5402 | .820 | 5304 |

| B Intra- | .731 | 33084 | .801 | 2651 | .762 | 2557 |

| C Intra- | .761 | 69850 | .826 | 5475 | .777 | 5389 |

| Multi-κ | .774 | .831 | .786 | |||

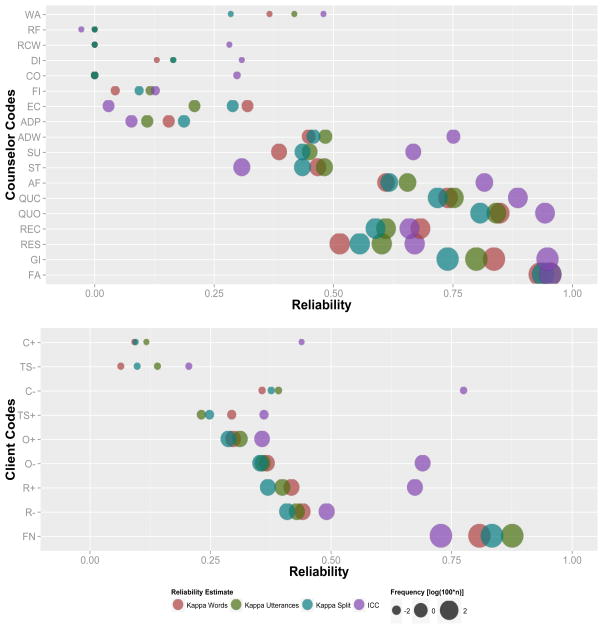

We assessed reliability for all individual MISC codes. A more detailed view of reliability for individual MISC codes as calculated by the four methods is presented in Figure 2. (Note: Figure 2 is in color.) The size of the points is scaled to reflect frequency of the codes where larger points indicate greater instances of a given code. When comparing ICCs to Cicchetti’s (1994) standards of agreement, 45% of codes (n = 15) attained “good” to “excellent” agreement (Range .66 to .95), 12% (n = 4) were “fair” (Range .40 to .50) and the remaining 43% (n = 14) had “poor” agreement (Range -.03 to .36). When examining reported ICCs in comparison to other MISC studies, our study reports similar or better agreement for many individual codes (Giving Information (GI) = .95; Open and Closed Questions (QUO, QUC) = .94; Affirmations (AF) = .79; Reason-Desire (R–D) = .78; Commitment- (C-) = .78; Simple Reflection (RES) = .67, etc.). Figure 2 reveals that ICC reliability based on session totals is larger on average relative to any of the three utterance-based Kappa measures. In Figure 2, codes are ordered by their frequency and a strong relationship between reliability and code frequency is observed. Infrequent codes contain very little information, as confidence intervals for infrequent codes (not shown) are very wide; thus, small differences in agreement can lead to poor reliability. Because this is fundamentally an issue of little information, true reliability could be anywhere across a wide range of values.

Figure 2.

Inter-rater reliability by method and MISC code (n = 31).

Note. Counselor Codes: WA = Warn; RF = Reframe; RCW = Raise Concern with Permission; DI = Direct; CO = Confront; FI = Filler; EC = Emphasize Control; ADP = Advice with Permission; ADW = Advice without Permission; SU = Support; ST = Structure; AF = Affirmation; QUC = Closed Question; QUO = Open Question; REC = Complex Reflection; RES = Simple Reflection; GI = Giving Information; FA = Facilitate. Client Codes: C+ = Commitment Change Talk; TS- = Taking Steps Sustain Talk; C- = Commitment Sustain Talk; TS+ = Taking Steps Change Talk; O+ = Other Change Talk; O- = Other Sustain Talk; R+ = Reason Change Talk; R- = Reason Sustain Talk; FN = Follow/Neutral.

4. Discussion

Why does MI work and what is high-quality MI? The gold-standard method of studying these questions involves the use of behavioral coding systems such as the MISC. The current research demonstrates that collecting MISC data on a per-utterance basis is feasible and allows for more accurate estimates of code frequencies, reliability, and more refined analyses of disagreements. We demonstrated that it is possible to reliably code behavior codes on the utterance-level without pre-parsing transcripts or assessing reliability on the session-level. Because we did not collapse codes across volleys and coded every utterance, we also obtained an accurate estimate of the ratio between Follow/Neutral and change and sustain talk utterances (82% of client speech was Follow/Neutral; 9% was change talk) that has not been previously reported.

Based on the current analyses, summing MISC codes across a session and estimating reliability using these tallies can lead to biased estimates of reliability. Although not universally true, for a number of codes, the ICCs were notably higher than the utterance-based Kappas. Several codes appeared to have moderate agreement when using ICC and approximately zero agreement when evaluated on the utterance-level (e.g., commitment language, C+ = .01 using “split utterance” method versus .44 using a session level ICC); this means that the coders are identifying roughly a similar amount of a given code in the interview, but may not identify the same utterances as meeting criteria for that code. It should be further noted that the discrepancy between ICCs and the utterance-level methods of assessing reliability were more severe for theoretically important codes (such as subtypes of change talk) and less severe for codes that appeared with more frequency, but are less important to understanding how MI works (e.g., Follow/Neutral). More generally, given that the codes are assigned to specific utterances, there is a clear preference for utterance-based reliability (i.e., Kappa) in the face of any disagreement, whether higher or lower. The Kappa reliabilities also include parsing reliability in their estimates, which also provides a better estimate of coding, broadly understood.

The current paper presented three alternative methods of estimating Kappa given parsing differences among coders. There is not a “ground truth” against which to compare these three, but the matching split utterances method provided a moderate approach that did not over- or under-estimate reliability. Matching split utterances allowed for comparison of coder data with varied parsing and did not exclude any data.

Though many behavior codes reached high agreement, the primary reason for low agreement was low frequency of occurrence. The association between frequency and reliability has been noted previously (Bakeman, McArthur, Quera, & Robinson, 1997; Moyers et al., 2009). Like other reliability analyses using the MISC, in our study some of the most theoretically interesting codes occurred less often and had relatively low reliability (e.g., selected change-talk codes, counselor emphasize control and support, and counselor MI inconsistent codes such as warn, confront). This is particularly concerning given that so much of MI practice theory relies on the hypothetical relationship between change talk and behavior change. Inconsistent or unreliable identification of change talk may be one reason some studies have reported a strong relationship between change talk and behavior change (Moyers et al., 2007; Moyers, Martin, Houck, Christopher, & Tonigan, 2009), whereas others have found mixed support (Gaume, Gmel, Daeppen, 2008) or no support (Vader et al., 2010). In our study, poor behavior code agreement would likely have improved if our sample had a greater frequency of rare codes.

An alternative proposal to increase behavior code agreement would be to identify which codes are more reliably confused than others for a particular coding team and train the team to distinguish these codes consistently (see Supplementary Appendix for further discussion). Additional psychometric work with utterance-based codes may help to better delineate the hierarchical structure of the MISC. Finally, to the extent that MISC codes are encoding semantic meaning, text-mining approaches such as topic models (Atkins et al., 2012) may offer alternative methods for validating or updating MISC codes and their hierarchy.

A final observation is that coders appeared almost as likely to drift from agreeing with their own coding as they were to drift from agreeing with the other coders. One hypothesis for the small difference in inter- and intra- reliability could be that coders drifted away from personal definitions of the codes and closer to the group coding criteria (and thus sacrificed intra-rater for inter-rater agreement) over time. This hypothesis could be explored in future studies. Another hypothesis for the small difference in between and within coder reliability is that the MISC coding system is too complicated to consistently apply in a real-world sample to the extent that behavior codes, as they are currently defined, cannot be reliably distinguished by one person coding the same session twice. Given the structure of the MISC with a high number of potential behavior codes, it is possible that it is ultimately impossible to achieve good to excellent agreement on all codes. The difficulties attaining statistical power for sequential or utterance-level analyses given the high number of possible codes have been previously noted by the creators of the MI-SCOPE (Martin et al., 2005, p. 16). Thus, we should consider whether the Cicchetti (1994) standard of agreement can be reliably attained in the context of coding an MI therapy session using the MISC and human coders.

4.1 Limitations and Areas of Future Inquiry

Limitations of the present study should be noted. It is possible that these methods for assessing reliability could be used in conjunction with other utterance-level coding schemes like the MI-SCOPE (Martin et al., 2005) that currently utilize pre-parsing. Applications to the MI-SCOPE and other coding schemes could be important for future practical applications of coding. A copy of detailed procedural information regarding coding and transcription guidelines used in the present study can be provided upon request to the authors (Marin et al., 2013).

The impact of the MI style coder training also could not be fully assessed because the trainers were rated on MI adherence using a fidelity measure and there was no comparison group of coders that were trained in a more directive method. Future studies could explore the impact of adherence to MI style while training and giving feedback to coding teams using a rating system like the MITI.

4.2. Conclusion

Psychotherapy is fundamentally a conversation between two people. When therapy is successful, something in that conversation prompted behavior change; yet, this simple characterization belies the challenge of studying psychotherapy. MI researchers are at the forefront of understanding therapy mechanisms, and behavioral coding like the MISC represent some of the leading methods in that exploration. The current research explores the precision of MI research tools and their common use. In the present work, technology was applied in a novel way to assist in data collection and to estimate the precision of the MISC. In the future, our hope is that continued creative utilization of technological developments will assist the broader goal of understanding what in the MI conversation leads to behavior change. Our team has continued to apply these novel methods in efforts to assist in the development in technology-based assessments of MI fidelity that could ultimately scale-up MI dissemination efforts (Atkins, Steyvers, Imel & Smyth, 2014; Imel et al., 2014).

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

We used the MISC 2.1 to rate motivational interviewing from 5 alcohol and drug use trials

We compared 3 methods of utterance-based coding reliability to traditional reliability estimates

Session-level ICCs were higher than reliability using utterance-based codes

Typical methods for assessing MISC reliability may be biased

Acknowledgments

The present research was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01AA018673. The original randomized trials were supported by grants from NIAAA (R01/AA016979, R01/AA014741) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01/DA025833, R01/DA026014). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The authors acknowledge the contribution of Theresa Kim for assistance in coordinating the research study and Taylor Gillian, James Darin and Keven Huang for coding the audiotaped sessions. In addition, we thank the original principal investigators who allowed access to and provided consultation on their data: Drs. Peter Roy-Byrne, Mary Larimer, Christine Lee, and Clayton Neighbors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could a3ect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Atkins DC, Rubin TN, Steyvers M, Doeden MA, Baucom BR, Christensen A. Topic models: A novel method for modeling couple and family text data. Journal of Family Psychology. 2012;26(5):816–827. doi: 10.1037/a0029607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins DC, Steyvers M, Imel ZE, Smyth P. Scaling up the evaluation of psychotherapy: evaluating motivational interviewing fidelity via statistical text classification. Implementation Science. 2014;9(1):49. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-9-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Beadnell B, Garrett SB, Hartzler B, Wells EA, Peterson PL. Adolescent change language within a brief motivational intervention and substance use outcomes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22(4):570–575. doi: 10.1037/a0013022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakeman R, McArthur D, Quera V, Robinson BF. Detecting sequential patterns and determining their reliability with fallible observers. Psychological Methods. 1997;2(4):357–370. doi: 10.1037//1082-989X.2.4.357. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett E, Spruijt-Metz D, Unger JB, Sun P, Rohrbach LA, Sussman S. Boosting a teen substance use prevention program with motivational interviewing. Substance Use & Misuse. 2012;47(4):418–428. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.641057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barras C, Geoffrois E, Wu Z, Liberman M. Transcriber: Development and use of a tool for assisting speech corpora production. Speech Communication. 2001;33(1):5–22. [Google Scholar]

- Boardman T, Catley D, Grobe JE, Little TD, Ahluwalia JS. Using motivational interviewing with smokers: Do therapist behaviors relate to engagement and therapeutic alliance? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2006;31(4):329–339. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudahmane K, Manta M, Antoine F, Galliano S, Barras C. Transcriber software. 1998 http://trans.sourceforge.net/en/presentation.php.

- Campbell SD, Adamson SJ, Carter JD. Client language during motivational enhancement therapy and alcohol use outcome. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2010;38(4):399–415. doi: 10.1017/S1352465810000263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Can D, Georgiou PG, Atkins DC, Narayanan SS. A case study: Detecting counselor reflections in psychotherapy for addictions using linguistic features. Paper presented at the Proceedings of InterSpeech; Portland, OR. 2012. Sep, [Google Scholar]

- Catley D, Harris KJ, Mayo MS, Hall S, Okuyemi KS, Boardman T, Ahluwalia JS. Adherence to principles of motivational interviewing and client within-session behavior. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2006;34(1):43–56. doi: 10.1017/S1352465805002432. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Jonge JM, Schippers GM, Schaap CPDR. The motivational interviewing skill code: Reliability and a critical appraisal. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2005;33(3):285–298. doi: 10.1017/S1352465804001948. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn C. Personal communication. 2013. Apr 1,

- Gaume J, Bertholet N, Faouzi M, Gmel G, Daeppen J-B. Does change talk during brief motivational interventions with young men predict change in alcohol use? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2012;44(2):177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaume J, Gmel G, Faouzi M, Daeppen JB. Counsellor behaviours and patient language during brief motivational interventions: A sequential analysis of speech. Addiction. 2008;103(11):1793–1800. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaume J, Gmel G, Daeppen JB. Brief alcohol interventions: Do counsellors' and patients' communication characteristics predict change? Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2008;43(1):62–69. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agm141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glynn LH, Hallgren KA, Houck JM, Moyers TB. CACTI: Free, open-source software for the sequential coding of behavioral interactions. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(7):e39740. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houck JM, Moyers TB, Miller WR, Glynn LH, Hallgren KA. Elicit Coding Manual: Motivational Interviewing Skill Code (MISC) 2.5. Albuquerque, NM: Center on Alcoholism, Substance Abuse, and Addictions, The University of New Mexico; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Imel ZE, Barco J, Brown H, Baucom BR, Baer J, Kircher J, Atkins DC. The association of therapist empathy and synchrony in vocally encoded arousal. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2014;61:146–153. doi: 10.1037/a0034943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohavi R, Provost F. Glossary of terms. Machine Learning. 1998;30:271–274. [Google Scholar]

- Krupski A, Josech J, Dunn C, Donovan D, Bumgardner K, Lord SP, Roy-Byrne P. Testing the effects of brief intervention in primary care for problem drug use in a randomized controlled trial: Rationale, design, and methods. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice. 2012;7(1):27. doi: 10.1186/1940-0640-7-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CM, Kilmer JR, Neighbors C, Atkins DC, Zheng C, Walker DD, Larimer ME. Indicated prevention for college student marijuana use: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2013;81(4):702–709. doi: 10.1037/a0033285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CM, Neighbors C, Lewis MA, Kaysen D, Mittmann A, Geisner IM, Larimer ME. Randomized controlled trial of a Spring Break intervention to reduce high-risk drinking. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2014;82(2):189–201. doi: 10.1037/a0035743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundahl B, Kunz C, Brownell C, Tollefson D, Burke B. A meta-analysis of motivational interviewing: Twenty-five years of empirical studies. Research on Social Work Practice. 2010;20(2):137–160. doi: 10.1177/1049731509347850. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Magill M, Gaume J, Apodaca TR, Walthers J, Mastroleo NR, Borsari B, Longabaugh R. The technical hypothesis of motivational interviewing: A meta-analysis of MI's key causal model. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2014 doi: 10.1037/a0036833. E-publication ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin R, Can D, Georgiou P. Addiction research study transcription manual (Version 1.3; 3-25-2013) University of Washington; University of Southern California; Seattle, WA; Los Angeles, CA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Martin T, Moyers TB, Houck JM, Christopher PJ, Miller WR. Motivational interviewing sequential code for observing process exchanges (MI-SCOPE) coder’s manual. 2005 doi: 10.1037/a0033041. Retrieved from http://casaa.unm.edu/download/scope.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Martin T, Christopher PJ, Houck JM, Moyers TB. The structure of client language and drinking outcomes in project match. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2011;25(3):439–445. doi: 10.1037/a0023129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Moyers TB, Ernst DB, Amrhein PC. Manual for the Motivational Interviewing Skill Code (MISC), Version 2.1. New Mexico: Center on Alcoholism, Substance Abuse, and Addictions, The University of New Mexico; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people to change addictive behavior. New York, NY US: Guilford Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2. New York, NY US: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Helping people change. 3. New York, NY US: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB. Personal communication. 2011. Jan 20,

- Moyers TB, Martin T. Therapist influence on client language during motivational interviewing sessions. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2006;30(3):245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Martin T, Manuel JK, Miller WR, Ernst DB. Revised Global Scales: Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity 3.1.1 (MITI 3.1.1) 2010 Retrieved from http://casaa.unm.edu/download/MITI3_1.pdf.

- Moyers TB, Martin T, Catley D, Harris K, Ahluwalia JS. Assessing the integrity of motivational interviewing interventions: Reliability of the motivational interviewing skills code. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2003;31(2):177–184. doi: 10.1017/S1352465803002054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Martin T, Christopher PJ, Houck JM, Tonigan JS, Amrhein PC. Client language as a mediator of motivational interviewing efficacy: Where is the evidence? Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31(Suppl 3):40S–47S. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Martin T, Houck JM, Christopher PJ, Tonigan JS. From in-session behaviors to drinking outcomes: A causal chain for motivational interviewing. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(6):1113–1124. doi: 10.1037/a0017189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Miller WR, Hendrickson SML. How does motivational interviewing work? Therapist interpersonal skill predicts client involvement within motivational interviewing sessions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73(4):590–598. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan S, Georgiou PG. Behavioral signal processing: Deriving human behavioral informatics from speech and language. Proceedings of the IEEE. 2013;101(5):1203–1233. doi: 10.1109/JPROC.2012.2236291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Lee CM, Atkins DC, Lewis MA, Kaysen D, Mittmann A, Larimer ME. A randomized controlled trial of event-specific prevention strategies for reducing problematic drinking associated with 21st birthday celebrations. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80(5):850–862. doi: 10.1037/a0014386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norcross John C, Wampold Bruce E. Evidence-Based Therapy Relationships. Psychotherapy. 2011;48(1):98–102. doi: 10.1037/a0022161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychological Bulletin. 1979;86(2):420–428. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.86.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tappin DM, Lumsden M, McIntyre D, McKay C, Gilmour WH, Webber R, Currie F. A pilot study to establish a randomized trial methodology to test the efficacy of a behavioural intervention. Health Education Research. 2000;15(4):491–502. doi: 10.1093/her/15.4.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tollison SJ, Lee CM, Neighbors C, Neil TA, Olson ND, Larimer ME. Questions and reflections: The use of motivational interviewing microskills in a peer-led brief alcohol intervention for college students. Behavior Therapy. 2008;39(2):183–194. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2007.07.0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.