Abstract

Various mechanisms have been demonstrated to be operative in bacterial adhesion to surfaces, but whether bacterial adhesion to surfaces can ever be captured in one generally valid mechanism is open to question. Although many papers in the literature make an attempt to generalize their conclusions, the majority of studies of bacterial adhesion comprise only two or fewer strains. Here we demonstrate that three strains isolated from a medical environment have a decreasing affinity for substrata with increasing surface free energy, whereas three strains from a marine environment have an increasing affinity for substrata with increasing surface free energy. Furthermore, adhesion of the marine strains related positively with substratum elasticity, but such a relation was absent in the strains from the medical environment. This study makes it clear that strains isolated from a given niche, whether medical or marine, utilize different mechanisms in adherence, which hampers the development of a generalized theory for bacterial adhesion to surfaces.

Bacterial adhesion to surfaces, the first step in the formation of a biofilm, has been studied extensively over the past decades in many diverse areas, such as in biomaterials implanted in the human body and on ship hulls and in the food industry. Bacterial adhesion has been regarded either from a specific, biochemical point of view as an interaction between complementary surface components (5) or from a nonspecific, physicochemical point of view. Physicochemical mechanisms of bacterial adhesion involve either a thermodynamic model (1), based on measured contact angles with liquids on the interacting surfaces followed by calculation of interfacial free energies, or the DLVO (Derjaguin, Landau, Verwey, Overbeek) theory (13), in which adhesion is regarded as the total sum of Lifshitz-Van der Waals, acid-base, and electrostatic interactions. The so-called “fouling triangle” (8) defines a combination of roughness, hydrophobicity, and mechanical properties of a substratum surface that discourages bacterial adhesion.

All of the mechanisms mentioned above have been demonstrated to be operative, although most studies dealing with mechanisms of bacterial adhesion to surfaces have included only a few strains. The results of a literature search using WinSPIRS in the SilverPlatter MEDLINE database (search and retrieval software; Ovid Technologies Inc., Amsterdam, The Netherlands) for the years 2002 and 2003 to determine the number of strains involved in papers with the key word “bacterial adhesion” and those describing certain physicochemical properties are presented in Table 1. The conclusions of at least 45 papers were substantiated by the inclusion of a maximum of two strains. Often, papers involving three strains or more demonstrated mere trends, with small or no statistical significance, while studies comprising one or two strains frequently yielded opposite conclusions. Bos et al. (3) published a review of 266 papers and concluded that bacterial adhesion is unlikely ever to be captured in one generally valid mechanism. The relation between bacterial deposition rates and attractive or repulsive electrostatic interactions was suggested to be generally valid.

TABLE 1.

Number of papers involving one or more strains determined by a literature search for the years 2002 and 2003a

| Keyword(s) | No. of papers with no. of strains indicated

|

Total no. of papers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | >4 | ||

| “Bacterial adhesion” | ||||||

| And “hydrophobicity” or “surface energy” or “contact angle” | 24 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 9 | 50 |

| And “surface charge” or “zeta potential” | 6 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 14 |

| And “roughness” | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

Search was done using WinSPIRS in SilverPlatter MEDLINE database (Ovid Technologies).

The problems concerning generalization are partly related to the lack of a good and universally accepted methodology to study bacterial adhesion to surfaces (3). Many recent studies still use slight rinsing or dipping to remove loosely adhering bacteria, without the realization that all adhering organisms can be regarded as loosely adhering if the rinsing forces applied are sufficiently high (6, 10). The literature is therefore fouled with studies confusing the definitions of two terms: adhesion and retention (7). Generalization is also impeded by the complexity of bacterial cell surfaces at the nanometer level, which can today be assessed through the application of atomic-force microscopy (AFM) (4, 12).

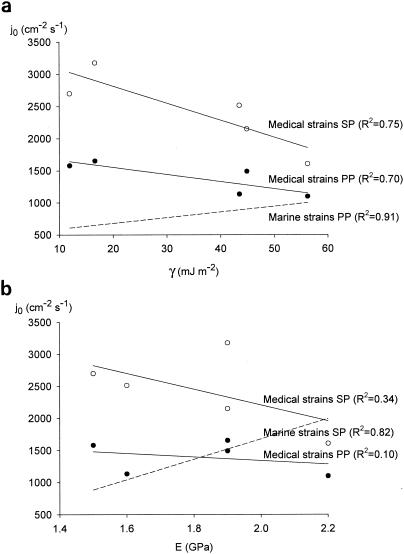

Recently, we evaluated the effects of surface free energy and elasticity, as parts of the fouling triangle, on adhesion of three marine strains with low, intermediate, and high cell surface hydrophobicities (Marinobacter hydrocarbonoclasticus ATCC 27132, Halomonas pacifica ATCC 27122, Psychrobacter sp. strain SW5H, respectively) to polyurethanes with different elasticities and hydrophobicities. To eliminate the effect of bacterial cell surface hydrophobicity, the initial deposition rates of the three strains were averaged. Figure 1 summarizes the significant relationships obtained in two different flow chambers, namely, a parallel plate flow chamber and a stagnation point flow chamber (2). Since these polyurethane coatings are potentially also of use in the biomedical field, we studied the adhesion to these coatings of three bacterial strains that were isolated from infected implants and that also possessed different cell surface hydrophobicities (i.e., Staphylococcus epidermidis GB 9/6, Acinetobacter baumannii 2, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa 3). The aim of this paper is to demonstrate how experiments within the same laboratory, using identical adhesion methodologies and substrata, done with two collections of strains isolated from different niches can lead to different conclusions.

FIG. 1.

Average initial deposition rates (j0) of three marine and three medical strains to different polyurethane coatings and glass in the parallel plate flow chamber (PP) (closed symbols) and stagnation point flow chamber (SP) (open symbols) as a function of surface free energy γ (a) and elasticity modulus (b). Solid lines indicate the results with the best fit, whereas dashed lines indicate the results obtained from similar experiments with marine strains (2).

Experiments were carried out at a flow rates of 0.050 ml s−1 for the parallel plate flow chamber and 0.0088 ml s−1 for the stagnation point flow chamber, values corresponding with a common shear rate of 22.5 s−1 and a common Péclet number of 1.05 × 10−3 (2). The Reynolds numbers for the parallel plate and stagnation point flow chambers were 1.3 and 2.6, respectively, well within the limits for laminar flow. Marine bacteria were suspended in artificial seawater, and medical implant strains were suspended in adhesion buffer, both to a density of 3 × 108 per ml (2). The rate of initial deposition, a measure of the affinity of a bacterium for the substratum, was determined from the initial increase of the number of adhering bacteria per unit area and time.

Figure 1a shows that adhesion of the medical implant strains decreased with increasing surface free energy of the substrata in both flow chambers. This decrease is statistically less significant than the increase with increasing substratum surface free energy observed for the marine strains in the parallel plate flow chamber. Figure 1b shows that the decrease in bacterial adhesion in both flow chambers with increasing substratum elasticity can at best be called a trend, opposite to the behavior of the marine bacteria in the stagnation point flow chamber.

The opposite responses of the two different collections of strains raise the question of whether it will ever be possible to generalize the influence of the physicochemical properties on bacterial adhesion to substrata. Obviously, although valid conclusions can be drawn for three strains from the same habitat, extrapolation from one habitat to another appears to be impossible. Biomaterials implant-related strains have a sensitivity (i.e., the slope of the line) to changes in substratum surface free energy similar to that of the marine strains in the parallel plate flow chamber, whereas the sensitivity of the implant-related strains is higher in the stagnation point flow chamber due to the different modes of mass transport. The sensitivities toward substratum elasticity are roughly similar for both collections of strains in the stagnation point flow chamber, despite the fact that the slopes have opposite directions. As noted previously (3), we found that the adhesion properties of a collection of oral streptococci followed surface thermodynamics quite well, whereas the adhesion properties of a collection of staphylococci seemed at odds with surface thermodynamics. The introduction of the AFM will probably enable researchers to reveal adhesion mechanisms at a nanometer level (4, 12); however, the AFM measures interaction forces that subsequently translate into adhesion patterns that are yet poorly understood because adhesion is the result of interplay between interaction forces and prevailing environmental detachment forces.

Organisms isolated from any given niche, whether medical, environmental, water, or industrial, will have different mechanisms of adhesion and retention, not only because the substrata, nutrients, ionic strength, pH values, and temperatures differ, but also because the structural components, such as fibrils, fimbriae, elasticities, and adhesive surface proteins, have adapted differently over time through selective pressures, including environmental detachment forces (9, 11). Such adaptation may also occur by overly subculturing strains in the laboratory. Leach et al. (9) demonstrated clearly that approximately half of the streptococci obtained from human saliva manifested fimbriae as an aid in adhesion and, thus, survival in the oral cavity that were lost upon subculture in broth.

In summary, we conclude that it is difficult to generalize findings regarding the mechanisms of bacterial adhesion, especially when applying findings beyond the habitat of the strains under consideration. In addition to the complexity of bacterial cell surfaces, there are a number of other issues contributing to this difficulty. (i) Many bacterial adhesion studies are not carried out under controlled hydrodynamic conditions and involve the mislabeled “slight rinsing” to remove “loosely” bound bacteria. Such studies deal not with bacterial adhesion but, rather, with bacterial retention (7). (ii) In a reductionistic approach to bacterial adhesion, it is important to gather detailed information on the adhesion mechanism of one particular bacterial strain before studying another strain. A reductionistic approach is scientifically sound and often preferred but provides only a slow pathway to the development of generalized mechanisms and often also yields a poor reflection of real life. (iii) A teleological approach, in which the total cultivable microflora in urine, saliva, or seawater is examined in adhesion studies, yields much more relevant results that can be more quickly generalized but does not yield a detailed understanding of the process of bacterial adhesion as such.

REFERENCES

- 1.Absolom, D. R., F. V. Lamberti, Z. Policova, W. Zingg, C. J. van Oss, and W. Neumann. 1983. Surface thermodynamics of bacterial adhesion. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 46:90-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bakker, D. P., F. M. Huijs, J. de Vries, J. W. Klijnstra, H. J. Busscher, and H. C. van der Mei. 2003. Bacterial deposition to fluoridated and non-fluoridated polyurethane coatings with different elasticity and surface free energy in a parallel plate and a stagnation point flow chamber. Colloids Surf. B 32:179-190. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bos, R., H. C. van der Mei, and H. J. Busscher. 1999. Physico-chemistry of initial microbial adhesive interactions—its mechanisms and methods for study. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 23:179-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Camesano, T. A., and B. E. Logan. 2000. Probing bacterial electrosteric interactions using atomic force microscopy. Environ. Sci. Technol. 34:3354-3362. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dalton, H. M., and P. E. March. 1998. Molecular genetics of bacterial attachment and biofouling. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 9:252-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dang, Y. N., A. Rao, P. R. Kastl, R. C. Blake, M. J. Schurr, and D. A. Blake. 2003. Quantifying Pseudomonas aeruginosa adhesion to contact lenses. Eye Contact Lens 29:65-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gómez-Suárez, C., H. J. Busscher, and H. C. van der Mei. 2001. Analysis of bacterial detachment from substratum surfaces by the passage of air-liquid interfaces. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:2531-2537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krupers, M. 2000. Cleanability of surfaces. Eur. Coat. J. 10:36-40. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leach, S. A., K. J. Swindin, and K. C. Shaw. 1985. The restoration of fimbriae to laboratory-grown streptococci by the oral environment, p. 63-74. In P. O. Glantz, S. A. Leach, and T. Ericson (ed.), Oral interfacial reactions of bone, soft tissue and saliva. IRL Press Ltd., Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 10.Tanner, J., A. Carlen, E. Soderling, and P. K. Vallittu. 2003. Adsorption of parotid saliva proteins and adhesion of Streptococcus mutans ATCC 21752 to dental fiber-reinforced composites. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 66B:391-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomas, W. E., E. Trintchina, M. Forero, V. Vogel, and E. V. Sokurenko. 2002. Bacterial adhesion to target cells enhanced by shear force. Cell 109:913-923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vadillo-Rodriguez, V., H. J. Busscher, W. Norde, J. de Vries, and H. C. van der Mei. 2004. Relations between macroscopic and microscopic adhesion of Streptococcus mitis strains to surfaces. Microbiology 150:1015-1022. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Van Oss, C. J., R. J. Good, and M. K. Chaudhury. 1986. The role of Van der Waals forces and hydrogen bonds in hydrophobic interactions between biopolymers and low energy surfaces. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 111:378-390. [Google Scholar]