Abstract

AIM: To determine the difference in clinical outcome between ulcerative colitis (UC) patients with Mayo endoscopic subscore (MES) 0 and those with MES 1.

METHODS: UC patients with sustained clinical remission of 6 mo or more at the time of colonoscopy were examined for clinical outcomes and the hazard ratios of clinical relapse according to MES. Parameters, including blood tests, to identify predictive factors for MES 0 and slight endoscopic recurrence in clinically stable patients were assessed. Moreover, a receiver operating characteristic curve was generated, and the area under the curve was calculated to indicate the utility of the parameters for the division between complete and partial mucosal healing. All P values were two-sided and considered significant when less than 0.05.

RESULTS: A total of 183 patients with clinical remission were examined. Patients with MES 0 (complete mucosal healing: n = 80, 44%) were much less likely to relapse than those with MES 1 (partial mucosal healing: n = 89, 48%) (P < 0.0001, log-rank test), and the hazard ratio of risk of relapse in patients with MES 1 vs MES 0 was 8.17 (95%CI: 4.19-17.96, P < 0.0001). The platelet count (PLT) < 26 × 104/μL was an independent predictive factor for complete mucosal healing (OR = 4.1, 95%CI: 2.15-7.99). Among patients with MES 0 at the initial colonoscopy, patients of whom colonoscopy findings shifted to MES 1 showed significant increases in PLT compared to those who maintained MES 0 (3.8 × 104/μL vs -0.6 × 104/μL, P < 0.0001).

CONCLUSION: The relapse rate differed greatly between patients with complete and partial mucosal healing. A shift from complete to partial healing in clinically stable UC patients can be predicted by monitoring PLT.

Keywords: Ulcerative colitis, Mucosal healing, Platelet count, Mayo endoscopic subscore, Platelet count

Core tip: Mucosal healing has been recognized as the treatment goal of ulcerative colitis (UC). Although many previous reports defined mucosal healing as Mayo endoscopic subscore (MES) of 0 or 1, the difference in prognosis between patients with MES 0 and those with MES 1 has scarcely been evaluated. This paper indicated that the relapse rate differed greatly between patients with MES 0 and MES 1, and that the treatment goal of UC should be MES 0. We also demonstrated that a shift from MES 0 to MES 1 in clinically stable UC patients can be predicted by monitoring platelet count.

INTRODUCTION

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is an idiopathic chronic inflammatory disorder that affects the innermost lining or mucosa of the colon and rectum, manifesting as continuous areas of inflammation and ulceration with no segments of normal tissue[1]. UC patients have symptoms such as diarrhea and bloody stool, unless appropriate treatment is provided. Aminosalicylates are the usual first-line treatment for UC and 60%-70% of patients with mild to moderate UC respond to them. Corticosteroid treatment is considered for patients with more severe symptoms, when aminosalicylates are not effective. However, despite treatment with appropriate medications, including other immunosuppressive agents, a considerable proportion of patients suffer from uncomfortable symptoms that continue or recur. Ultimately, 20%-30% of patients are likely to require colectomy[2].

Current opinions increasingly cite the need to achieve not only a clinical response but also mucosal healing in the treatment of UC, as evaluated on colonoscopy. Mucosal healing is associated with sustained clinical remission and reduced rates of hospitalization and surgical resection[3]. In addition, a recent study indicated that early mucosal healing after administration of infliximab for UC was correlated with improved clinical outcomes, including avoidance of colectomy[4]. Another report showed that lack of mucosal healing after initial corticosteroid therapy was associated with late negative outcomes[5]. However, standard criteria for the evaluation of disease severity and definitions of mucosal healing are not available at present[6]. In particular, some reports defined mucosal healing as a Mayo endoscopic subscore (MES) of 0 or 1[4,7], while others defined this as an MES of 0 only[8]. Undetermined definitions of mucosal healing have complicated the interpretation of the significance of mucosal healing in the treatment of UC. In this context, the difference in long-term prognosis, including relapse of clinical symptoms and colectomy, between clinically asymptomatic patients with MES 0 (complete mucosal healing) and those with MES 1 (partial mucosal healing) has been reported rarely. Moreover, if the prognosis is better for patients with MES 0, surrogate markers differentiating patients with MES 0 from patients with MES 1 are required urgently because of the physical and economical burden of colonoscopy.

In this study, therefore, the colonoscopic findings of UC patients with sustained clinical remission were meticulously reevaluated and subdivided into MES 0 and MES 1 or more. Based on this classification, patient prognosis, including relapse of clinical symptoms and colectomy rate, was examined. Moreover, items of blood testing differentiating patients with MES 0 from those with MES 1 were evaluated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

All the colonoscopy records of UC patients who periodically visited Okayama University Hospital and underwent colonoscopy for evaluation of disease activity or surveillance between January 2006 and December 2012 were reviewed. In our institute, blood samples are taken on the day of colonoscopy for the measurement of biochemical values, including albumin and C-reactive protein (CRP), and a full blood count. All of the patients had an established diagnosis of UC, according to endoscopic and histologic assessments, and had received medical therapy.

Clinical disease activity was evaluated using the Mayo score, consisting of the following 4 subscores: stool frequency (0, normal number for this patient; 1, 1-2 stools more than normal; 2, 3-4 stools more than normal; and 3, ≥ 5 stools more than normal), rectal bleeding (0, no blood seen; 1, streaks of blood with stool less than half the time; 2, obvious blood with stool most of the time; and 3, blood alone passes), endoscopic findings (0, normal or inactive disease; 1, mild disease with erythema, decreased vascular pattern, mild friability; 2, moderate disease with marked erythema, absent vascular pattern, friability, erosions; and 3, severe disease with spontaneous bleeding, ulceration), and physician’s global assessment (0, normal; 1, mild disease; 2, moderate disease; and 3,severe disease)[9]. Clinical remission was defined as a Mayo stool frequency subscore of 0 or 1 and a Mayo rectal bleeding subscore of 0[4], and clinical relapse was defined as increasing or modification of concomitant medications due to worsening of symptoms.

This study is comprised of analyses of the colonoscopic findings, laboratory data, and clinical courses of UC patients with clinical remission. Patients with sustained clinical remission of 6 mo or more at the time of colonoscopy were considered eligible for this retrospective cohort study.

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of Okayama University Graduate School of Medicine, Dentistry, and Pharmaceutical Sciences. Informed consent was obtained from each patient.

Colonoscopy

On the day of the colonoscopy, patients received a polyethylene glycol-based or magnesium citrate-based electrolyte solution for bowel preparation, according to the instructions for use. After the colonic lavage, patients underwent colonoscopy. Patients were excluded if the colonoscopic examination was incomplete because of problems with the bowel preparation or if the colonoscope could not be inserted into the cecum.

The mucosal status of UC was assessed using the MES classification. Evaluation was performed at each portion of the colorectum (cecum, ascending, transverse, descending, and sigmoid colon, and rectum), and the maximum score in the colorectum of each patient was used for analysis. An MES of “0” throughout the colorectum was defined as complete mucosal healing, while a maximum MES of “1” in the colorectum was defined as partial mucosal healing.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using the JMP program (version 9, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, United States). A Kaplan-Meier curve of estimated duration of sustained clinical remission was generated for each patient group with MES 0-2, and comparisons between the groups were performed using a 2-side log-rank test. The Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for clinical relapse among each group. Comparative models such as the χ2 test and Mann-Whitney test were used for cross-sectional analysis of categorical data. In order to identify predictive factors for complete mucosal healing in the target patients, univariate and multivariate analyses were performed using a logistic regression model with corresponding calculations of odds ratios (ORs) and 95%CIs. Moreover, a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was generated, and the area under the curve was calculated to indicate the utility of the parameters for the division between complete and partial mucosal healing. All P values were two-sided and considered significant when less than 0.05.

RESULTS

Clinical characteristics of the patients

A total of 715 colonoscopies were performed in 295 UC patients between January 2006 and December 2012. Among these patients, 183 had maintained clinical remission for 6 mo or more at the time of colonoscopy. In the initial analysis, when patients had undergone two or more colonoscopies during clinical remission continuing more than 6 mo, only the data of the first colonoscopy were included. Accordingly, the initial analysis was of 183 patients/colonoscopies. Table 1 shows the clinical characteristics of the 183 patients (93 male and 90 female; median age at UC onset 32 years). Colonoscopy findings revealed that the maximum MES was 0 in 80 (44%) cases, 1 in 89 (48%) cases, and 2 in 14 (8%) cases. Based on our definitions, 80 and 89 patients had complete and partial mucosal healing, respectively.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of analyzed patients n (%)

| Patients | Value |

| Total | 183 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 93 (51) |

| Female | 90 (49) |

| Extent of disease | |

| Pancolitis | 112 (61) |

| Left-side colitis | 40 (22) |

| Proctitis | 31 (17) |

| Median (IQR) age at onset | 32 (22-45) |

| Median (range) duration of disease, mo | 108 (54-202) |

| Median (range) age of undergoing colonoscopy | 44 (33-59) |

| Concomitant medications | |

| Aminosalicylate | 163 (89) |

| Corticosteroids | 23 (13) |

| Mercaptopurine/azathioprine | 70 (38) |

| Tacrolimus | 5 (3) |

| Biologics | 7 (4) |

| Colonoscopy findings (maximum index in the colorectum) | |

| MES 0 | 80 (44) |

| MES 1 | 89 (48) |

| MES 2 | 14 (8) |

MES: Mayo endoscopic subscore; IQR: Interquartile range.

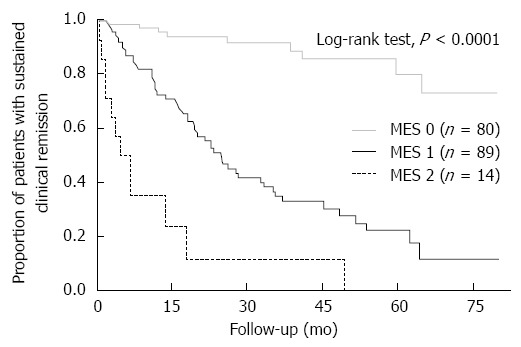

Difference in prognosis of UC patients according to the MES

Kaplan-Meier curves of maintenance of clinical remission are shown for the patients with MES 0, 1 or 2 in Figure 1. The cumulative remission maintenance rate showed statistically significant differences among patients with each MES (P < 0.0001, log-rank test). The Cox proportional hazards model indicated that patients with MES 1 and those with MES 2 had a significantly higher risk of clinical relapse than patients with complete mucosal healing (MES 1: HR = 8.17, 95%CI: 4.19-17.96, P < 0.0001; MES 2: HR = 31.16, 95%CI: 12.80-78.83, P < 0.0001). In addition, the risk of hospitalization and the need for rescue corticosteroids were also higher in patients with MES 1 than those with MES 0 (HR = 10.48, 95% CI, 1.90-195.22, P = 0.0044; and HR = 27.31, 5.69-490.06, P < 0.0001, respectively). These results suggest that patients who achieved complete mucosal healing (MES 0) were much less likely to suffer a relapse than those who achieved only partial mucosal healing (MES 1), as well as those with endoscopic active inflammation (MES 2). The risk of colectomy or occurrence of dysplasia/cancer did not differ significantly among patients with each MES (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves of maintenance of clinical remission for patients with Mayo endoscopic subscore 0, 1 or 2. The cumulative remission maintenance rate showed statistically significant differences among patients with each Mayo endoscopic subscore (MES).

Clinical characteristics of patients with complete mucosal healing (MES 0) vs those with mucosal inflammation (MES 1 or 2)

We have shown that achievement of complete mucosal healing (MES 0) is optimal for UC patients with regard to maintenance of clinical remission. Then, we compared the clinical characteristics of patients in clinical remission with complete mucosal healing to those of patients without complete mucosal healing. Of the 183 patients, 80 achieved complete mucosal healing (MES 0), while the remaining 103 showed only partial healing (MES 1) or more inflammation (MES 2) (Table 2). The former were significantly older at disease onset (49 years vs 40 years, P = 0.009) and at baseline colonoscopy (36 years vs 29 years, P = 0.009) than the latter. Hematological examination revealed that white blood cell count (WBC) and platelet count (PLT) were significantly lower in the patients with complete mucosal healing than in those without (5160/μL vs 5660/μL, P = 0.017, and 24.7 × 104/μL vs 29.1 × 104/μL, P < 0.0001, respectively).

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients with Mayo endoscopic subscore 0 vs 1 or 2 n (%)

| Characteristics | MES 0 (n = 80) | MES 1, 2 (n = 103) | P value |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 45 (56) | 48 (47) | 0.2 |

| Female | 35 (44) | 55 (53) | |

| Median age, yr (IQR) | 49 (37-62) | 40 (32-54) | 0.009 |

| Median duration of disease, mo (IQR) | 98 (52-213) | 122 (57-202) | 0.73 |

| Median age at onset, yr (IQR) | 36 (25-50) | 29 (19-40) | 0.009 |

| Extent of disease | |||

| Pancolitis | 42 (53) | 70 (68) | 0.1 |

| Left-side colitis | 21 (26) | 19 (18) | |

| Proctitis | 17 (21) | 14 (14) | |

| Concomitant medications | |||

| Aminosalicylate | 72 (90) | 91 (88) | 0.72 |

| Corticosteroids | 12 (15) | 11 (11) | 0.38 |

| Mercaptopurine/azathioprine | 28 (35) | 42 (41) | 0.43 |

| Tacrolimus | 3 (4) | 2 (2) | 0.46 |

| Biologics | 2 (3) | 5 (5) | 0.41 |

| Blood markers, median (IQR) | |||

| CRP (mg/L) | 0.4 (0.2-1.0) | 0.5 (0.2-1.2) | 0.3 |

| WBC (/μL) | 5160 (4130-5990) | 5660 (4830-6800) | 0.017 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 13.6 (12.4-15.0) | 13.5 (12.4-14.7) | 0.75 |

| PLT (× 104/μL) | 24.7 (21.7-27.6) | 29.1 (25.6-33.4) | < 0.0001 |

| Alb (g/dL) | 4.5 (4.2-4.8) | 4.4 (4.1-4.7) | 0.17 |

MES: Mayo endoscopic subscore; IQR: Interquartile range; CRP: C-reactive protein; WBC: White blood cell; Hb: Hemoglobin; PLT: Platelet count; Alb: Albumin.

Predictive factors of complete mucosal healing in patients with sustained clinical remission

Univariate and multivariate analyses of factors that predict complete mucosal healing in patients with sustained clinical remission were performed using parameters including patient age (at baseline colonoscopy and at onset) and hematological variables, including WBC, hemoglobin, PLT, albumin and CRP (Table 3). The cutoff value of each parameter was determined by ROC curve analysis to discriminate patients with complete mucosal healing (MES 0) from those without. Factors associated with complete mucosal healing in the univariate analysis were age at baseline colonoscopy > 48 years, age at onset > 32 years, WBC < 5900/μL, and PLT < 26 × 104/μL. Furthermore, multivariate analysis revealed that WBC < 5900/μL and PLT < 26×104/μL were independent predictive factors for MES 0 in patients with sustained clinical remission (WBC < 5900/μL, OR = 2.37, 95%CI: 1.19-4.81, PLT < 26 × 104/μL; OR = 4.1, 95%CI: 2.15-7.99, respectively).

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analysis for factors predictive of Mayo endoscopic subscore 0

| OR | Univariate analysis95%CI | P value | OR | Multivariate analysis95%CI | P value | |

| Age > 48 yr | 2.59 | 1.42-4.78 | 0.002 | 1.88 | 0.79-4.52 | 0.15 |

| Age at onset > 32 yr | 2.39 | 1.32-4.38 | 0.004 | 1.46 | 0.61-3.46 | 0.39 |

| WBC < 5900/μL | 2.65 | 1.43-5.05 | 0.002 | 2.37 | 1.19-4.81 | 0.014 |

| PLT < 26 × 104/μL | 4.74 | 2.55-9.01 | < 0.0001 | 4.10 | 2.15-7.99 | < 0.0001 |

WBC: White blood cell; PLT: Platelet count.

The sensitivity and specificity of each and combinations of these two criteria for MES 0 are shown in Table 4. The predictive values for MES 0 of WBC only and PLT only were not satisfactory. However, fulfillment of either criterion predicted MES 0 with 0.91 (95%CI: 0.85-0.95) sensitivity, and the specificity for MES 0 of fulfillment of both criteria was 0.82 (95%CI: 0.76-0.87). These results suggest that combinations of WBC and PLT are useful for predicting complete mucosal healing among patients with sustained clinical remission.

Table 4.

Predictive values of white blood cell and platelet count for Mayo endoscopic subscore 0 in patients with sustained clinical remission

| WBC < 5900/μLonly | PLT < 26 × 104/μLonly | Either WBC < 5900/μL or PLT < 26 × 104/μL | Both WBC < 5900/μL and PLT < 26 × 104/μL | |

| Sensitivity (95%CI) | 0.74 (0.66-0.81) | 0.65 (0.57-0.72) | 0.91 (0.85-0.95) | 0.48 (0.40-0.54) |

| Specificity (95%CI) | 0.49 (0.42-0.54) | 0.72 (0.66-0.77) | 0.39 (0.34-0.42) | 0.82 (0.76-0.87) |

WBC: White blood cell; PLT: Platelet count; MES: Mayo endoscopic subscore.

Parameters predicting change of mucosal status from complete mucosal healing to partial mucosal healing

Thus, maintenance of complete mucosal healing is an ultimate goal for UC patients and WBC and PLT could be useful predictors of complete mucosal healing. However, there is the problem that WBC and PLT vary among patients, even though their mucosal status is similar. In clinical settings, it is more important to recognize the shift of mucosal status from complete mucosal healing to partial healing in the individual patient with continuous clinical remission, because patients in continuous clinical remission usually would prefer not to receive colonoscopy after confirmation of MES 0 by previous colonoscopy.

To resolve this issue, we examined, in a second analysis, the patients who underwent colonoscopy twice or more during maintenance of clinical remission after the finding of MES 0 at the first colonoscopy. The change of colonoscopic findings was compared with the changes of the laboratory data of those patients. Of 80 patients in clinical remission with the finding of MES 0 at the first colonoscopy, 47 underwent a further colonoscopy during the maintenance of clinical remission. The second colonoscopy revealed that 26 (55%) patients maintained the MES of 0, while the findings of the remaining 21 (45%) changed from MES 0 to MES 1. Table 5 shows the differences in characteristics at the first colonoscopy and hematological variables between the first and the second colonoscopies of each patient group. Among the variables examined, PLT alone had increased significantly in patients in whom the MES changed from 0 to 1, compared to patients who maintained MES 0 (+3.8 × 104/μL vs -0.6 × 104/μL, P < 0.0001). The ROC curve of change in PLT for identifying the shift from MES 0 to MES 1 had an area under curve of 0.86 (Figure 2). These results suggest that an increase in PLT during the follow-up of UC patients with complete clinical and endoscopic remission indicates slight endoscopic recurrence, which subsequently leads to a condition susceptible to clinical recurrence.

Table 5.

Change in blood marker values in patients with or without maintenance of complete mucosal healing n (%)

| Variables | Maintenance of MES 0 (n = 26) | Shift to MES 1 (n = 21) | P value |

| Extent of disease | |||

| Pancolitis | 13 (50) | 13 (62) | |

| Left-side colitis | 10 (38) | 3 (14) | |

| Proctitis | 3 (12) | 5 (24) | 0.15 |

| Median (IQR) age at onset | 36 (27-49) | 28 (23-43) | 0.2 |

| Median (range) duration of disease, mo | 132 (55-220) | 152 (64-244) | 0.65 |

| Change in values of parameters | |||

| median (IQR) | |||

| ΔCRP (mg/L) | 0.1 (-0.1-0.4) | 0 (0.2-0.4) | 0.95 |

| ΔWBC (/μL) | -200 (-1680-780) | 280 (-330-1030) | 0.16 |

| ΔHb (g/dL) | 0.1 (-0.3-0.8) | 0.4 (-0.1-0.8) | 0.25 |

| ΔPLT (× 104/μL) | -0.6 (-2.4-1.5) | 3.8 (1.5-8.0) | < 0.0001 |

| ΔAlb (g/dL) | 0.1 (-0.2-0.3) | 0 (-0.1-0.2) | 0.82 |

MES: Mayo endoscopic subscore; IQR: Interquartile range, CRP: C-reactive protein; WBC: White blood cell; Hb: Hemoglobin; PLT: Platelet count; Alb: Albumin.

Figure 2.

Receiver operating characteristic curve of change in platelet count for identifying the shift from Mayo endoscopic subscore 0 to 1 in patients with clinical remission. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of change in platelet count for identifying the shift from Mayo endoscopic subscore (MES) 0 to MES 1 had an area under curve of 0.86. When cut-off value of change in platelet count was determined as 1.3 × 104/μL, the sensitivity and specificity were 0.81 and 0.73, respectively.

DISCUSSION

With the accumulation of evidence for the value of mucosal healing in Crohn’s disease[10,11], mucosal healing has been regarded as an important clinical goal in UC. The follow-up study of the Active UC Trials (ACT-1, 2) showed that mucosal healing after 8 wk of starting infliximab was correlated with improved clinical outcomes, including avoidance of colectomy[4]. Moreover, several additional studies indicated that mucosal healing in UC can alter the course of the disease with reductions in hospitalization rates and surgical resections[12], and by lowering the risk of dysplasia and adenocarcinoma of the colon[12-14].

However, standard criteria for the evaluation of disease severity and definitions of mucosal healing of UC are not available at present[6]. Although many previous clinical studies defined mucosal healing as an MES of 0 or 1[4,7], long-term studies examining whether an MES of 0 or MES of 1 actually contributes to maintenance of clinical remission in UC patients are scarce. Detailed analysis of the ACT-1, 2 studies showed that the clinical remission rate after 54 wk was 73% in patients with an MES of 0 on colonoscopy performed after induction of remission (week 8) but 47% in those with an MES of 1, indicating that more than half of the latter patients had relapse[4]. However, the same study also showed that the rate of corticosteroid-free clinical remission after 54 wk was lower in patients with an MES of 0 at week 8 than in those with an MES of 1 (46% vs 63%)[4]. Meucci et al[8] reported in a study evaluating the effectiveness of mesalazine for maintenance of remission that a significant difference was not observed in the rate of relapse at 1 year between patients with an MES of 0 and those with an MES of 1. These two reports had similar drawbacks in that the results were obtained in very specific situations (infliximab users only or users of mesalazine alone) and in a short-term (1 year for both studies), although these are just two of the very few studies referring to the difference in clinical course between patients with MES 0 and MES 1. Hence, the data of the difference in clinical significance between MES 0 and MES 1 have absolutely been lacking.

In this study, therefore, we assessed the difference in long-term clinical outcomes between patients in clinical remission with MES 0 and MES 1 and showed that patients with MES 0 were much less likely to relapse. The result was consistent with that of a recent small-scale study from Japan[15]. Although these are retrospective studies, analysis of a general UC cohort and long-term follow-up are a strength. Our relatively large cohort analysis strongly suggests that complete mucosal healing should be the treatment goal of UC.

In addition, we identified surrogate makers that could differentiate complete from partial mucosal healing in patients with clinical remission. Previously, several noninvasive surrogate markers have been suggested for the endoscopic activity of UC. In particular, blood or fecal markers would be ideal if sufficiently predictive. However, most such studies calculated predictive values for endoscopically active status[16,17], suggesting that prediction of mucosal healing by surrogate markers is more difficult. In this regard, our previous report was unique, indicating the performance of a fecal immunochemical test, which is widely used as a screening modality for colorectal cancer, on evaluation of mucosal healing of UC patients[18]. In that study, we indicated that a fecal hemoglobin concentration < 60 ng/mL predicted MES 0 with 94% sensitivity and 74% specificity.

On this background, one of the highlights of this study is the identification of blood markers (combinations of WBC < 5900/μL and PLT < 26 × 104/μL) that discriminated complete mucosal healing (MES 0) from partial healing (MES 1) with sufficient sensitivity and specificity, because patients with clinical remission in these two categories differ significantly as to relapse rate. Surrogate markers for mucosal healing have been reported rarely, even when both MES 0 and 1 are included, although predicting mucosal healing is more clinically relevant than predicting endoscopic inflammation. Hence, our finding of markers of discrimination of MES 0 from MES 1 in patients with clinical remission should have a great impact on the clinical practice of UC treatment.

Moreover, we found that PLT increased significantly in patients of whom the MES changed from 0 to 1, compared to patients who maintained MES 0. This indicates that the worsening of endoscopic findings of patients in clinical remission, without any change of symptoms, can be recognized by an increase in PLT. Undergoing repeated colonoscopies to evaluate complete or partial mucosal healing is difficult for patients in clinical remission, because colonoscopy is burdensome. In addition to the colonoscopy procedure itself, bowel preparations, possible worsening of disease after colonoscopy, and high cost are matters of concern to patients. Therefore, validation of complete mucosal healing by monitoring PLT instead of performing colonoscopy is helpful for both patients and physicians.

Many clinicians who treat inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) have been aware of platelet elevation in IBD patients with clinical activity. In fact, previous reports carried out hematological examinations on UC patients with and without activity and healthy controls and showed that the mean platelet count was higher in patients with active disease than in inactive UC or healthy controls[19,20]. Thus, to some extent, PLT have been regarded as a biomarker reflecting mucosal inflammation in IBD, although the correlation with mucosal status, particularly mucosal healing, has been reported rarely. Although the mechanism for predicting activity in IBD is largely unknown, platelets are broadly activated in inflammatory responses and tissue injury[21,22], and activated platelets express CD40 ligand through which they can specifically interact with a large number of CD40-bearing immune and non-immune cells[23]. This causal correlation may be attributed to the fact that CD40 ligand-positive platelets are present in the circulation of patients with several inflammatory conditions[24-26], including IBD[27].

Our finding that lower levels of WBC and PLT are correlated with complete mucosal remission may be partly attributed to the use of thiopurines. Thiopurines are widely used for maintenance of clinical remission of IBD patients. In IBD patients who take thiopurines, lower WBC have been regarded as a good predictor of achievement and maintenance of remission[28,29]. This well known fact suggests that the degree of myelosuppression parallels the efficacy of thiopurines. In this regard, both WBC and PLT reflected the degree of myelosuppression and may be correlated with complete mucosal healing, that is, deeper clinical remission in thiopurine users. However, because the rate of use of thiopurine did not differ significantly between patients with MES 0 and those with MES 1 or 2 in our cohort, there is still room for investigation of the correlation between the efficacy of thiopurine and mucosal healing.

A limitation of this study is the retrospective design in a single hospital. However, because this is an observational study of clinical practices without any intervention, the study design would not have caused great bias.

In conclusion, our study revealed that the clinical prognosis of UC patients in clinical remission differs between those with complete endoscopic remission (MES 0) and those without. Complete mucosal healing should be a treatment goal of UC to improve long-term outcomes. We also demonstrated that blood markers can predict complete mucosal healing and a shift from complete to partial mucosal healing in clinically stable UC patients. Our findings could greatly improve clinical practice of UC patients, particularly those in clinical remission.

COMMENTS

Background

Mucosal healing in ulcerative colitis (UC) is associated with sustained clinical remission and reduced rates of hospitalization and surgical resection.

Research frontiers

Standard criteria for the evaluation of disease severity and definitions of mucosal healing are not available at present. The difference in clinical outcome between patients with Mayo endoscopic subscore (MES) 0 (complete mucosal healing) and those with MES 1 (partial mucosal healing) is not completely understood. Moreover, appropriate surrogate markers of mucosal healing have not yet been established.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Patients with complete mucosal healing (MES 0) were much less likely to relapse than those with partial mucosal healing (MES 1) and, therefore, MES 0 should be a treatment goal of UC. Additionally, this is the first study to demonstrate that platelet count (PLT) is one of the predictors of MES 0 and that monitoring PLT is helpful for recognizing slight endoscopic recurrence without colonoscopy.

Applications

The endoscopic features of the appropriate treatment goal of UC were indicated. The surrogate markers of the treatment goal (i.e., complete mucosal healing) such as PLT were shown. The additional results were that monitoring PLT would be helpful to find out slight endoscopic recurrence without performing colonoscopy. All of these findings would be useful in economical and patient- and physician-friendly follow-up of UC patients.

Peer review

This is a carefully done study and the findings are of considerable interest. This article reveals that the recurrence rate of UC is higher in patients with partial mucosal healing than complete mucosal healing. A shift from complete to partial healing in clinically stable UC patients can be predicted by monitoring PLT.

Footnotes

P- Reviewer: Akarsu M, Deepak P, Luo HS S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

References

- 1.Head KA, Jurenka JS. Inflammatory bowel disease Part 1: ulcerative colitis--pathophysiology and conventional and alternative treatment options. Altern Med Rev. 2003;8:247–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turner D, Walsh CM, Steinhart AH, Griffiths AM. Response to corticosteroids in severe ulcerative colitis: a systematic review of the literature and a meta-regression. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:103–110. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pineton de Chambrun G, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Lémann M, Colombel JF. Clinical implications of mucosal healing for the management of IBD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7:15–29. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2009.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colombel JF, Rutgeerts P, Reinisch W, Esser D, Wang Y, Lang Y, Marano CW, Strauss R, Oddens BJ, Feagan BG, et al. Early mucosal healing with infliximab is associated with improved long-term clinical outcomes in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1194–1201. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ardizzone S, Cassinotti A, Duca P, Mazzali C, Penati C, Manes G, Marmo R, Massari A, Molteni P, Maconi G, et al. Mucosal healing predicts late outcomes after the first course of corticosteroids for newly diagnosed ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:483–489.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neurath MF, Travis SP. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel diseases: a systematic review. Gut. 2012;61:1619–1635. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reinisch W, Sandborn WJ, Hommes DW, D’Haens G, Hanauer S, Schreiber S, Panaccione R, Fedorak RN, Tighe MB, Huang B, et al. Adalimumab for induction of clinical remission in moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis: results of a randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2011;60:780–787. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.221127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meucci G, Fasoli R, Saibeni S, Valpiani D, Gullotta R, Colombo E, D’Incà R, Terpin M, Lombardi G. Prognostic significance of endoscopic remission in patients with active ulcerative colitis treated with oral and topical mesalazine: a prospective, multicenter study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:1006–1010. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schroeder KW, Tremaine WJ, Ilstrup DM. Coated oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis. A randomized study. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1625–1629. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198712243172603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schnitzler F, Fidder H, Ferrante M, Noman M, Arijs I, Van Assche G, Hoffman I, Van Steen K, Vermeire S, Rutgeerts P. Mucosal healing predicts long-term outcome of maintenance therapy with infliximab in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1295–1301. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baert F, Moortgat L, Van Assche G, Caenepeel P, Vergauwe P, De Vos M, Stokkers P, Hommes D, Rutgeerts P, Vermeire S, et al. Mucosal healing predicts sustained clinical remission in patients with early-stage Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:463–468; quiz 463-468. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.09.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frøslie KF, Jahnsen J, Moum BA, Vatn MH. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease: results from a Norwegian population-based cohort. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:412–422. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rutter MD, Saunders BP, Wilkinson KH, Rumbles S, Schofield G, Kamm MA, Williams CB, Price AB, Talbot IC, Forbes A. Cancer surveillance in longstanding ulcerative colitis: endoscopic appearances help predict cancer risk. Gut. 2004;53:1813–1816. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.038505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta RB, Harpaz N, Itzkowitz S, Hossain S, Matula S, Kornbluth A, Bodian C, Ullman T. Histologic inflammation is a risk factor for progression to colorectal neoplasia in ulcerative colitis: a cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1099–105; quiz 1340-1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yokoyama K, Kobayashi K, Mukae M, Sada M, Koizumi W. Clinical Study of the Relation between Mucosal Healing and Long-Term Outcomes in Ulcerative Colitis. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013;2013:192794. doi: 10.1155/2013/192794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenberg L, Lawlor GO, Zenlea T, Goldsmith JD, Gifford A, Falchuk KR, Wolf JL, Cheifetz AS, Robson SC, Moss AC. Predictors of endoscopic inflammation in patients with ulcerative colitis in clinical remission. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:779–784. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e3182802b0e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D’Haens G, Ferrante M, Vermeire S, Baert F, Noman M, Moortgat L, Geens P, Iwens D, Aerden I, Van Assche G, et al. Fecal calprotectin is a surrogate marker for endoscopic lesions in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:2218–2224. doi: 10.1002/ibd.22917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakarai A, Kato J, Hiraoka S, Kuriyama M, Akita M, Hirakawa T, Okada H, Yamamoto K. Evaluation of mucosal healing of ulcerative colitis by a quantitative fecal immunochemical test. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:83–89. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kapsoritakis AN, Koukourakis MI, Sfiridaki A, Potamianos SP, Kosmadaki MG, Koutroubakis IE, Kouroumalis EA. Mean platelet volume: a useful marker of inflammatory bowel disease activity. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:776–781. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kayahan H, Akarsu M, Ozcan MA, Demir S, Ates H, Unsal B, Akpinar H. Reticulated platelet levels in patients with ulcerative colitis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22:1429–1435. doi: 10.1007/s00384-007-0330-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lefer AM. Platelets: unindicted coconspirators in inflammatory tissue injury. Circ Res. 2000;87:1077–1078. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.12.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rizvi M, Pathak D, Freedman JE, Chakrabarti S. CD40-CD40 ligand interactions in oxidative stress, inflammation and vascular disease. Trends Mol Med. 2008;14:530–538. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Henn V, Slupsky JR, Gräfe M, Anagnostopoulos I, Förster R, Müller-Berghaus G, Kroczek RA. CD40 ligand on activated platelets triggers an inflammatory reaction of endothelial cells. Nature. 1998;391:591–594. doi: 10.1038/35393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garlichs CD, Eskafi S, Raaz D, Schmidt A, Ludwig J, Herrmann M, Klinghammer L, Daniel WG, Schmeisser A. Patients with acute coronary syndromes express enhanced CD40 ligand/CD154 on platelets. Heart. 2001;86:649–655. doi: 10.1136/heart.86.6.649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khan SY, Kelher MR, Heal JM, Blumberg N, Boshkov LK, Phipps R, Gettings KF, McLaughlin NJ, Silliman CC. Soluble CD40 ligand accumulates in stored blood components, primes neutrophils through CD40, and is a potential cofactor in the development of transfusion-related acute lung injury. Blood. 2006;108:2455–2462. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-017251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Phipps RP, Kaufman J, Blumberg N. Platelet derived CD154 (CD40 ligand) and febrile responses to transfusion. Lancet. 2001;357:2023–2024. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)05108-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Danese S, Katz JA, Saibeni S, Papa A, Gasbarrini A, Vecchi M, Fiocchi C. Activated platelets are the source of elevated levels of soluble CD40 ligand in the circulation of inflammatory bowel disease patients. Gut. 2003;52:1435–1441. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.10.1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Colonna T, Korelitz BI. The role of leukopenia in the 6-mercaptopurine-induced remission of refractory Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:362–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fraser AG, Orchard TR, Jewell DP. The efficacy of azathioprine for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: a 30 year review. Gut. 2002;50:485–489. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.4.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]