Abstract

Avian hepatitis E virus (HEV), a novel virus identified from chickens with hepatitis-splenomegaly syndrome in the United States, is genetically and antigenically related to human HEV. In order to further characterize avian HEV, an infectious viral stock with a known infectious titer must be generated, as HEV cannot be propagated in vitro. Bile and feces collected from specific-pathogen-free (SPF) chickens experimentally infected with avian HEV were used to prepare an avian HEV infectious stock as a 10% suspension of positive fecal and bile samples in phosphate-buffered saline. The infectivity titer of this infectious stock was determined by inoculating 1-week-old SPF chickens intravenously with 200 μl of each of serial 10-fold dilutions (10−2 to 10−6) of the avian HEV stock (two chickens were inoculated with each dilution). All chickens inoculated with the 10−2 to 10−4 dilutions of the infectious stock and one of the two chickens inoculated with the 10−5 dilution, but neither of the chickens inoculated with the 10−6 dilution, became seropositive for anti-avian HEV antibody at 4 weeks postinoculation (wpi). Two serologically negative contact control chickens housed together with chickens inoculated with the 10−2 dilution also seroconverted at 8 wpi. Viremia and shedding of virus in feces were variable in chickens inoculated with the 10−2 to 10−5 dilutions but were not detectable in those inoculated with the 10−6 dilution. The infectivity titer of the infectious avian HEV stock was determined to be 5 × 105 50% chicken infectious doses (CID50) per ml. Eight 1-week-old turkeys were intravenously inoculated with 105 CID50 of avian HEV, and another group of nine turkeys were not inoculated and were used as controls. The inoculated turkeys seroconverted at 4 to 8 wpi. In the inoculated turkeys, viremia was detected at 2 to 6 wpi and shedding of virus in feces was detected at 4 to 7 wpi. A serologically negative contact control turkey housed together with the inoculated ones also became infected through direct contact. This is the first demonstration of cross-species infection by avian HEV.

Hepatitis E virus (HEV), the causative agent of hepatitis E, is an important human pathogen (1-2, 23-24, 26, 34-35). HEV is a positive-sense, single-stranded, nonenveloped RNA virus. The genome of HEV is about 7.2 kb and contains three open reading frames (ORFs) (23-24, 26). Hepatitis E is primarily transmitted through the fecal-oral route, with an incubation period of about 15 to 60 days. The mortality rate is generally low (about 1%); however, it can reach up to 15 to 25% among infected pregnant women (7, 23, 24). HEV is a public health concern in many developing countries; however, sporadic cases of acute hepatitis E have also been reported in many industrialized countries, including the United States (3, 13-14, 17, 20, 22, 26, 31, 33, 37).

Swine HEV, the first animal strain of HEV, was identified and characterized from a pig in the United States in 1997 (15). Many swine HEV isolates have since been identified worldwide and have been shown to be genetically closely related to genotypes 3 and 4 strains of human HEVs (5, 11, 19, 20, 29, 33, 36, 37). Recently, avian HEV, another animal strain of HEV, was identified from chickens with hepatitis-splenomegaly (HS) syndrome in the United States. Avian HEV was also demonstrated to be genetically and antigenically related to the known strains of human and swine HEVs (8-9). HS syndrome was first reported in 1991 in western Canada and then in the United States. The disease is characterized by increased rates of mortality among broiler breeder and laying chickens of 30 to 72 weeks of age as well as up to a 20% drop in egg production. Regressive ovaries, red fluid in the abdomen, and an enlarged liver and spleen were often seen in infected chickens with histological changes of hepatic necrosis and hemorrhage (25). Avian HEV has been genetically identified from chickens with HS syndrome as well as from healthy chickens (8, 10, 28). Avian HEV shares approximately 50 to 60% nucleotide sequence identities with known human and swine HEVs and approximately 80% sequence identity with the Australian chicken big liver and spleen disease virus (8-10, 21).

Cross-species infection by swine and human HEVs has been demonstrated, as a human HEV strain infected specific-pathogen-free (SPF) pigs and a swine HEV strain infected nonhuman primates (6, 16). Anti-HEV antibodies have also been detected in many animal species, and hepatitis E is considered a zoonosis (4, 12, 17, 18, 30). The objectives of this study were to generate an infectious stock of avian HEV, to determine the infectivity titer of this viral stock in young SPF chickens, and to attempt to experimentally infect SPF turkeys with avian HEV.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus.

The avian HEV strain used in the study was originally recovered from a bile sample from a naturally infected chicken with HS syndrome (8). Due to the limited amount of original avian HEV material, the virus was first amplified in 1-week-old SPF chickens (SPAFAS Inc., Norwich, Conn.) by intravenous inoculation of 0.1 ml of a original bile sample containing avian HEV diluted 1:100. A positive fecal sample collected at 28 days postinoculation (dpi) from an infected young SPF chicken was used to prepare a 10% fecal suspension in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The titer of avian HEV in the 10% fecal suspension is 104 genomic equivalents (GE)/ml, and this fecal suspension of avian HEV was used to generate an infectious stock of avian HEV.

Primer design.

The PCR primers used for the detection of avian HEV from fecal, serum, and bile samples from the experimentally inoculated SPF chickens and turkeys were based on the ORF1 helicase gene region (8, 10, 27). Primers AHEV F-1/S (5′-GAGCTTGTGAAGGGCGTTGAGG-3′) and AHEV R-1/S (5′-ACCCAAGATCAACGGCGCTC-3′) were used as the external primer set, and primers AHEV F-2/S (5′-CGGCAAGTCGTCGTCTGTTGACCAT-3′) and AHEV R-2/S (5′-CCCCCAGCATAACAACATCGCGC-3′) were used as the internal primer set. The sizes of the expected PCR products for the first and second rounds were 359 and 221 bp, respectively.

RNA extraction and RT-PCR.

RNA was extracted from 100 μl of each of the fecal, serum, and bile samples from chickens and turkeys with the TriReagent (Molecular Research Center, Inc.). Total RNA was resuspended in 12.25 μl of DNase-free, RNase-free, and proteinase-free water (Invitrogen). Reverse transcription (RT) was performed at 42°C for 60 min in the presence of a master mixture consisting of 12.25 μl of total RNA, 0.25 μl of Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen), 1 μl of 10 μM antisense primer, 0.5 μl of RNase inhibitor, 1 μl of 0.1 M dithiothreitol, 4 μl of 5× RT buffer, and 1 μl of 10 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates. The resulting cDNA was amplified by a nested RT-PCR with AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase (Applied Biosystems). The PCR parameters were 95°C for 9 min, followed by 39 cycles of amplification at 94°C for 1 min for denaturation, 52°C for 1 min for annealing, and 72°C for 1.5 min for extension, with a final incubation period at 72°C for 7 min. The PCR products were examined on a 0.8% agarose gel. PCR products from selected chickens and turkeys were sequenced to confirm the identities of the viruses recovered from experimentally infected birds.

ELISA for detection of anti-HEV antibody in chickens and turkeys.

A truncated recombinant ORF2 capsid protein of avian HEV was expressed in Escherichia coli strain BL21Star (DE3)pLysS (Invitrogen) and purified with a BugBuster His-Bind Purification kit (Novagen) (9, 10, 28). The purified avian HEV ORF2 protein was used as the antigen to standardize an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for the detection of avian HEV antibodies in chickens and turkeys as described previously (10). Briefly, the purified antigen was coated onto 96-well flat-bottom microtiter plates (Thermo Labsystems). Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated rabbit anti-chicken immunoglobulin G (IgG; Sigma) or HRP-conjugated goat anti-turkey IgG (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Inc.) was used as the secondary antibody for chicken and turkey sera, respectively. The cutoff values for these assays were set conservatively at 0.30, as described previously (10, 28). Sera from serologically negative SPF chickens and SPF turkeys were used as negative controls, and convalescent-phase sera from SPF chickens experimentally infected with avian HEV were included as positive controls. All sera were tested at least twice.

Generation of an infectious stock of avian HEV.

Since HEV cannot be propagated in cell culture, an infectious stock of avian HEV must be generated by using live animals. Ten 60-week-old SPF chickens (SPAFAS Inc.) were each inoculated intravenously with approximately 103 GE of avian HEV (0.1 ml of the 10% fecal suspension) and were monitored for 56 days. Feces were collected from all the inoculated chickens every 4 days. Two birds were necropsied at each of three time points, i.e., 12, 18, and 22 dpi; and the remaining ones were necropsied at 56 dpi. During each necropsy, bile and feces were collected from each chicken. Fecal and bile samples were tested for the presence of avian HEV RNA by RT-PCR.

Infectivity titration of the avian HEV stock in young SPF chickens.

The infectivity titer of the virus stock was determined in young SPF chickens. Briefly, 1-week-old SPF chickens (n = 30; SPAFAS Inc.) were randomly assigned to 10 isolators, each of which contained three chickens. The avian HEV stock was serially diluted 10-fold from 10−2 to 10−6 in PBS buffer. Each of the five dilutions was inoculated intravenously into two young SPF chickens (200 μl per chicken). Each inoculated chicken was housed in a separate isolator together with two serologically negative contact control chickens to assess the nature of avian HEV spread by direct contact. Serum samples were collected from each chicken every 2 weeks and were tested by ELISA for anti-avian HEV antibody seroconversion. Serum samples collected from each chicken were also tested for viremia, and fecal samples collected from each chicken once a week were tested for shedding of virus in feces by RT-PCR. The chickens were monitored for evidence of avian HEV infection for a total of 12 weeks. The infectivity titer of the avian HEV stock was calculated as the 50% chicken infectious dose (CID50) per milliliter of the virus inoculum.

Attempt to experimentally infect young SPF turkeys with avian HEV from a chicken.

To determine if avian HEV can infect across species, 18 SPF turkeys (age, 1 week; British United Turkeys of America, Lewisburg, W.Va.) were randomly assigned to two groups of nine turkeys each. A total of 200 μl of the avian HEV infectious stock (105 CID50) was inoculated intravenously into each of eight turkeys in one group; the remaining turkey in the group was not inoculated and was used as a contact control. The nine turkeys in the second group were uninoculated controls. Serum samples were collected from each turkey every 2 weeks and were tested by ELISA for anti-avian HEV antibody seroconversion. Serum samples collected from each turkey were also tested for viremia, and fecal samples collected from each turkey once a week were tested for shedding of virus in feces by RT-PCR.

RESULTS

Generation of an infectious stock of avian HEV.

Due to the limited amount of original bile sample containing avian HEV, we first amplified the virus in a 1-week-old SPF chicken. A 10% suspension of positive fecal material collected from an infected young SPF chicken was prepared. This 10% fecal suspension of avian HEV, which contained only approximately 104 GE/ml of avian HEV, was then used to intravenously inoculate 60-week-old SPF chickens (n = 10) to generate an infectious stock of avian HEV. Bile and feces collected during necropsies at 12, 18, and 22 dpi were positive for avian HEV RNA. Positive feces and bile samples from the four SPF chickens necropsied at 18 and 22 dpi were pooled to make a 10% suspension in PBS as an infectious stock of avian HEV. The viral stock was then aliquoted and stored at −80°C for further study.

Determination of the infectivity titer of an avian HEV stock in vivo.

Seroconversion in the inoculated chickens was used as the end point for the calculation of the infectivity titer of the virus stock (Table 1). Both chickens inoculated with the largest amount of virus, which was contained in the 10−2 dilution, became positive for anti-avian HEV antibody at 4 wpi. Two of the serologically negative contact control chickens housed in the same isolator as one of the two chickens inoculated with the 10−2 dilution also became positive for anti-avian HEV antibody 4 weeks after the inoculated one had seroconverted. The chickens inoculated with the 10−3 or 10−4 dilution also seroconverted. However, none of the contact control chickens in these two groups seroconverted. Only one of the two chickens inoculated with the 10−5 dilution seroconverted at 4 wpi. The chickens inoculated with the smallest amount of virus, which was contained in the 10−6 dilution, remained negative for avian HEV antibodies, viremia, or shedding of virus in feces (Table 1). Because each chicken received 200 μl of the virus stock, the infectious titer of the virus stock was calculated to be 5 × 105 CID50 per ml.

TABLE 1.

Anti-avian HEV antibody seroconversion by infectivity titration of an avian HEV stock in young SPF chickens

| Avian HEV stock dilution | Group | No. of chickens seropositive/ no. tested at the following wpi:

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 12 | ||

| 10−2 | Inoculated | 0/2 | 0/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 |

| Contact | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 2/4 | 2/4 | 2/4 | |

| 10−3 | Inoculated | 0/2 | 0/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 |

| Contact | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | |

| 10−4 | Inoculated | 0/2 | 0/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 |

| Contact | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | |

| 10−5 | Inoculated | 0/2 | 0/2 | 1/2 | 1/2 | 1/2 | 1/2 | 1/2 |

| Contact | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | |

| 10−6 | Inoculated | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 |

| Contact | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | |

Subclinical infection of young chickens by avian HEV in a dose-dependent manner.

All chickens inoculated with the 10−2 or the 10−3 dilution had transit viremia that lasted for approximately 1 week (Table 2). The viremia in one of the two chickens that received the 10−2 dilution (chicken 5357) lasted for 11 weeks. Avian HEV RNA was also detected from the bile sample from this chicken collected during necropsy at 12 wpi. Two of the contact control chickens in the group receiving the 10−2 dilution were also viremic, but the viremia occurred at 6 to 8 wpi. Chickens inoculated with the 10−4, 10−5, or 10−6 dilution did not develop viremia (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Viremia and shedding of avian HEV in feces in young chickens experimentally inoculated with different doses of an avian HEV stock

| Avian HEV stock dilution | Group | No. of chickens positive for viremia (shedding of virus in feces)/no. tested at the following wpi:

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 12 | ||

| 10−2 | Inoculated | 0 (0)/2 | NAa (1)/2 | 2 (2)/2 | NA (1)/2 | 1 (1)/2 | 1 (1)/2 | 1 (1)/2 | 1 (1)/2 | 1 (1)/2 |

| Contact | 0 (0)/4 | NA (0)/4 | 0 (0)/4 | NA (0)/4 | 0 (0)/4 | 1 (2)/4 | 2 (1)/4 | 1 (0)/4 | 0 (0)/4 | |

| 10−3 | Inoculated | 0 (0)/2 | NA (2)/2 | 2 (2)/2 | NA (0)/2 | 0 (0)/2 | 0 (0)/2 | 0 (0)/2 | 0 (0)/2 | 0 (0)/2 |

| Contact | 0 (0)/4 | NA (0)/4 | 0 (0)/4 | NA (0)/4 | 0 (0)/4 | 0 (0)/4 | 0 (0)/4 | 0 (0)/4 | 0 (0)/4 | |

| 10−4 | Inoculated | 0 (0)/2 | NA (0)/2 | 0 (2)/2 | NA (1)/2 | 0 (0)/2 | 0 (0)/2 | 0 (0)/2 | 0 (0)/2 | 0 (0)/2 |

| Contact | 0 (0)/4 | NA (0)/4 | 0 (0)/4 | NA (0)/4 | 0 (0)/4 | 0 (0)/4 | 0 (0)/4 | 0 (0)/4 | 0 (0)/4 | |

| 10−5 | Inoculated | 0 (0)/2 | NA (0)/2 | 0 (0)/2 | NA (1)/2 | 0 (0)/2 | 0 (0)/2 | 0 (0)/2 | 0 (0)/2 | 0 (0)/2 |

| Contact | 0 (0)/4 | NA (0)/4 | 0 (0)/4 | NA (0)/4 | 0 (0)/4 | 0 (0)/4 | 0 (0)/4 | 0 (0)/4 | 0 (0)/4 | |

| 10−6 | Inoculated | 0 (0)/2 | NA (0)/2 | 0 (0)/2 | NA (0)/2 | 0 (0)/2 | 0 (0)/2 | 0 (0)/2 | 0 (0)/2 | 0 (0)/2 |

| Contact | 0 (0)/4 | NA (0)/4 | 0 (0)/4 | NA (0)/4 | 0 (0)/4 | 0 (0)/4 | 0 (0)/4 | 0 (0)/4 | 0 (0)/4 | |

NA, serum samples were not available at this time point.

All chickens inoculated with the 10−2, 10−3, or 10−4 dilution shed avian HEV in their feces for 1 to 2 weeks (Table 2). Like viremia, one of the two chickens inoculated with the 10−2 dilution (chicken 5357) shed virus in its feces for 12 weeks. Two of the contact control chickens in the group receiving the 10−2 dilution also shed virus in their feces for 1 or 3 weeks at 6 to 8 weeks postinoculation. One of the two chickens inoculated with the 10−5 dilution also had a transit shedding of virus in its feces. None of the chickens in the 10−6 dilution group had detectable virus RNA in their feces (Table 2).

Cross-species infection of SPF turkeys with avian HEV from a chicken.

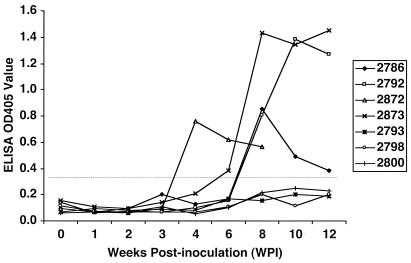

Since swine HEV was shown to infect across species (16, 17, 19), we conducted this study to determine if the virus from a chicken can cross species barriers and infect young SPF turkeys. All 18 turkeys were seronegative at the beginning of this study. The first inoculated turkey (turkey 2872) seroconverted to antibody positivity at 4 wpi (Table 3). By 8 wpi, all four remaining inoculated turkeys as well as the contact control turkey (which was housed together with the inoculated group) had become positive for anti-avian HEV antibody (Table 3). No seroconversion or viral RNA was detected in the uninoculated control turkeys. The course of anti-avian HEV antibody seroconversion in seven representative turkeys from this cross-species infection study is presented in Fig. 1. Two turkeys (turkeys 2788 and 2875) in the inoculated group died of anaphylaxis within 48 h postinoculation, and another two turkeys (turkeys 2776 and 2790) died prior to seroconversion during the routine blood collection process at 2 wpi. No gross pathological lessons attributable to avian HEV infection were found during necropsies of the dead birds. The remaining turkeys in this group were necropsied at 12 wpi, and no gross lesions in the livers or spleens were found.

TABLE 3.

Anti-avian HEV antibody seroconversion in turkeys experimentally inoculated with avian HEV from a chicken

| Group | Inoculum | Turkey no. | Seroconversion at the following wpia:

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 12 | |||

| I | Avian HEV | 2776 | − | − | −b | ||||||

| 2788 | −c | ||||||||||

| 2790 | − | − | −b | ||||||||

| 2791 | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | d | ||

| 2792 | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | ||

| 2872 | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | e | |||

| 2873 | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | ||

| 2875 | −c | ||||||||||

| Contact control | 2786 | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | |

| II | None | 2787, 2789, 2793, 2795 to 2800 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

−, negative; +, positive.

Two turkeys died during the routine blood collection process at 2 wpi.

Two turkeys died of anaphylaxis within 48 h postinoculation.

One turkey was necropsied at 11 wpi.

One turkey was necropsied at 9 wpi.

FIG. 1.

Cross-species infection of 1-week-old turkeys with avian HEV from a chicken: anti-avian HEV antibody seroconversion in seven representative turkeys. All turkeys were seronegative at the beginning of the study. Three inoculated turkeys (turkeys 2792, 2872, and 2873) and one serologically negative contact control turkey (turkey 2786) housed together with the inoculated ones became positive for anti-avian HEV antibody at 4 to 8 weeks wpi. Three uninoculated control turkeys (turkeys 2793, 2798, and 2800) housed separately from the inoculated ones remained seronegative. Prior to the end of the study, one inoculated turkey (turkey 2872) was necropsied at 9 wpi and blood samples were collected from this turkey only for the first 8 weeks.

Viremia was first detected from an inoculated turkey (turkey 2872) at 2 wpi (Table 4) and was then detected in two other inoculated turkeys at 4 and 6 wpi, respectively. Shedding of virus in feces also varied in the inoculated turkeys (Table 4). A 221-bp fragment within the helicase gene region of avian HEV from the experimentally infected turkeys was amplified by RT-PCR. After exclusion of the PCR primer sequences, only 173 bp of the resulting 221-bp partial helicase gene sequence was used for comparison. Sequence analyses revealed that the virus recovered from the experimentally infected turkeys was the same virus used in the inoculum.

TABLE 4.

Detection of avian HEV RNA in serum and fecal samples from turkeys experimentally inoculated with avian HEV from a chicken

| Group | Inoculum | Turkey no. | Detection of viral RNA in serum/feces at the following wpia:

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 10 | 12 | |||

| I | Avian HEV | 2776 | −/− | −/− | −/−b | ||||||||

| 2788 | −/−c | ||||||||||||

| 2790 | −/− | −/− | −/−b | ||||||||||

| 2791 | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | +/− | NAd/− | +/− | NA/+ | −/− | −/− | e | ||

| 2792 | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | NA/− | −/+ | NA/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | ||

| 2872 | −/− | −/− | +/− | +/− | −/+ | NA/− | −/− | NA/− | −/− | f | |||

| 2873 | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | NA/+ | +/+ | NA/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | ||

| 2875 | −/−c | ||||||||||||

| Contact control | 2786 | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | NA/− | −/− | NA/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | |

| II | None | 2787, 2789, 2793, 2795 to 2800 | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | −/− | NA/− | −/− | NA/− | −/− | −/− | −/− |

−, negative; +, positive.

Two turkeys died during the routine blood collection process at 2 wpi.

Two turkeys died of anaphylaxis within 48 h postinoculation.

NA, serum samples were not available at this time point.

One turkey was necropsied at 11 wpi.

One turkey was necropsied at 9 wpi.

DISCUSSION

In this study, an infectious stock of avian HEV was generated and its infectivity titer in SPF chickens was determined. In the absence of a cell culture system, this standardized infectious stock of avian HEV will be very useful for future characterization of the pathogenesis and replication of avian HEV. The infectivity titration experiment also showed that young SPF chickens can be easily infected by avian HEV by the intravenous route of inoculation. Viremia and shedding of virus in feces were transient in all except one inoculated chicken, in which viremia and shedding lasted for more than 10 weeks. The coexistence of anti-avian HEV antibody and viremia in this particular bird suggested that persistent infection with avian HEV might exist under some unknown conditions. The appearance of viremia and shedding of virus in feces is apparently dose dependent, as virus shedding in blood and feces appeared earlier in chickens inoculated with a higher dose than in those inoculated with a lower dose. This observation is consistent with those from the infectivity titration results in experiments with monkeys inoculated with human HEV (32).

It has previously been shown that swine HEV infects nonhuman primates and that human HEV infects pigs (6, 16). Therefore, after obtaining a standard infectious stock of avian HEV, we attempted to experimentally infect another avian species, turkeys, with avian HEV from a chicken. The inoculated turkeys became positive for anti-avian HEV antibody at 4 to 8 wpi, although not all infected turkeys had viremia or shed virus in their feces. This suggests that the avian HEV from chickens may replicate at a lower level in turkeys. The contact control turkey housed together with the inoculated ones became positive for anti-avian HEV antibody, but viremia and shedding of virus in feces were not detected in this contact bird. A 173-bp region within the helicase gene of the virus recovered from the experimentally infected turkeys was sequenced and was confirmed to originate from the inoculum. The demonstrated ability of cross-species infection by avian HEV suggests that avian HEV may infect species other than chickens under field conditions. Further studies are warranted to assess the range of host susceptibility of avian HEV and its potential zoonotic risk.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (grants AI01653, AI46505, and AI50611) and the U.S. Department of Agriculture National Research Initiative Competitive Grant Program (grant NRI 35204-12531).

We thank Mohamed Seleem for expert assistance with protein purification and Denis Guenette for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aggarwal, R., and K. Krawczynski. 2000. Hepatitis E: an overview and recent advances in clinical and laboratory research. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 15:9-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arankalle, V. A., M. S. Chadha, S. A. Tsarev, S. U. Emerson, A. R. Risbud, K. Banerjee, and R. H. Purcell. 1994. Seroepidemiology of water-borne hepatitis in India and evidence for a third enterically-transmitted hepatitis agent. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:3428-3432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Erker, J. C., S. M. Desai, G. G. Schlauder, G. J. Dawson, and I. K. Mushahwar. 1999. A hepatitis E virus variant from the United States: molecular characterization and transmission in cynomolgus macaques. J. Gen. Virol. 80:681-690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Favorov, M. O., M. Y. Kosoy, S. A. Tsarev, J. E. Childs, and H. S. Margolis. 2000. Prevalence of antibody to hepatitis E virus among rodents in the United States. J. Infect. Dis. 184:449-455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garkavenko, O., A. Obriadina, J. Meng, D. A. Anderson, H. J. Benard, B. A. Schroeder, Y. E. Khudaakov, H. A. Fields, and M. C. Croxson. 2001. Detection and characterization of swine hepatitis E virus in New Zealand. J. Med. Virol. 65:525-529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halbur, P. G., C. Kasorndorkbua, C. Gilbert, D. K. Guenette, M. B. Potters, R. H. Purcell, S. U. Emerson, T. E. Toth, and X. J. Meng. 2001. Comparative pathogenesis of infection of pigs with hepatitis E viruses recovered from a pig and a human. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:918-923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamid, S. S., S. M. Jafri, H. Khan, H. Shah, Z. Abbas, and H. Fields. 1996. Fulminant hepatic failure in pregnant women: acute fatty liver or acute viral hepatitis? J. Hepatol. 25:20-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haqshenas, G., H. L. Shivaprasad, P. R. Woolcock, D. H. Read, and X. J. Meng. 2001. Genetic identification and characterization of a novel virus related to human hepatitis E virus from chickens with hepatitis-splenomegaly syndrome in the United States. J. Gen. Virol. 82:2449-2462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haqshenas, G., F. F. Huang, M. Fenaux, D. K. Guenette, F. W. Pierson, C. T. Larsen, H. L. Shivaprasad, T. E. Toth, and X. J. Meng. 2002. The putative capsid protein of the newly identified avian hepatitis E virus shares antigenic epitopes with that of swine and human hepatitis E viruses and chicken big liver and spleen disease virus. J. Gen. Virol. 83:2201-2209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang, F. F., G. Haqshenas, H. L. Shivaprasad, D. K. Guenette, P. R. Woolcock, C. T. Larsen, F. W. Pierson, F. Elvinger, T. E. Toth, and X. J. Meng. 2002. Heterogeneity and seroprevalence of the newly identified avian hepatitis E virus from chickens in the United States. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:4197-4202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang, F. F., G. Haqshenas, D. K. Guenette, P. G. Halbur, S. Schommer, F. W. Pierson, T. E. Toth, and X. J. Meng. 2002. Detection by RT-PCR and genetic characterization of field isoltes of swine hepatitis E virus from pigs in different geographic regions of the United States. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:1326-1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kabrane-Lazizi, Y., J. B. Fine, J. Elm, G. E. Glass, H. Higa, A. Diwan, C. J. Gibbs, Jr., X. J. Meng, S. U. Emerson, and R. H. Purcell. 1999. Evidence for wide-spread infection of wild rats with hepatitis E virus in the United States. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 61:331-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mast, E. E., I. K. Kuramoto, M. O. Favorov, V. R. Schoening, B. T. Burkholder, C. N. Shapiro, and P. V. Holland. 1997. Prevalence of and risk factors for antibody to hepatitis E virus seroreactivity among blood donors in northern California. J. Infect. Dis. 176:34-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCrudden, R., S. O'Connell, T. Farrant, S. Beaton, J. P. Iredale, and D. Fine. 2000. Sporadic acute hepatitis E in the United Kingdom: an underdiagnosed phenomenon? Gut 46:732-733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meng, X. J., R. H. Purcell, P. G. Halbur, J. R. Lehman, D. M. Webb, T. S. Tsareva, J. S. Haynes, B. J. Thacker, and S. U. Emerson. 1997. A novel virus in swine is closely related to the human hepatitis E virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:9860-9865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meng, X. J., P. G. Halbur, M. S. Shapiro, S. Govindarajan, J. D. Bruna, I. K. Mushahwar, R. H. Purcell, and S. U. Emerson. 1998. Genetic and experimental evidence for cross-species infection by the swine hepatitis E virus. J. Virol. 72:9714-9721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meng, X. J. 2000. Novel strains of hepatitis E virus identified from humans and other animal species: is hepatitis E a zoonosis? J. Hepatol. 33:842-845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meng, X. J., B. Wiseman, F. Elvinger, D. K. Guenette, T. E. Toth, R. E. Engle, S. U. Emerson, and R. H. Purcell. 2002. Prevalence of antibodies to the hepatitis E virus in veterinarians working with swine and in normal blood donors in the United States and other countries. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:117-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meng, X. J. 2003. Swine hepatitis E virus: cross-species infection and risk in xenotransplantation. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 278:185-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nishizawa, T., M. Takahashi, H. Mizuo, H. Miyajima, Y. Gotanda, and H. Okamoto. 2003. Characterization of Japanese swine and human hepatitis E virus isolates of genotype IV with 99% identity over the entire genome. J. Gen. Virol. 84:1245-1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Payne, C. J., T. M. Ellis, S. L. Plant, A. R. Gregory, and G. E. Wilcox. 1999. Sequence data suggests big liver and spleen disease virus (BLSV) is genetically related to hepatitis E virus. Vet. Microbiol. 68:119-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pina, S., M. Buti, M. Cotrina, J. Piella, and R. Girones. 2000. HEV identified in serum from humans with acute hepatitis and in sewage of animal origin in Spain. J. Hepatol. 33:826-833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Purcell, R. H. 1996. Hepatitis E virus, p. 2831-2843. In B. N. Fields, D. M. Knipe, P. M. Howley, et al. (ed.), Fields virology, vol. 2, 3rd ed. Lippincott-Raven Publishers, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 24.Reyes, G. R. 1997. Overview of the epidemiology and biology of the hepatitis E virus, p. 239-258. In R. A. Willson (ed.), Viral hepatitis. Marcel Dekker, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 25.Riddell, C. 1997. Hepatitis-splenomegaly syndrome, p. 1041. In B. W. Calnek, H. J. Barnes, C. W. Beard, et al. (ed.), Diseases of poultry. Iowa State University Press, Ames.

- 26.Schlauder, G. G., and I. K. Mushahwar. 2001. Genetic heterogeneity of hepatitis E virus. J. Med. Virol. 65:282-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun, Z. F., F. F. Huang, P. G. Halbur, S. K. Schommer, F. W. Pierson, T. E. Toth, and X. J. Meng. 2003. Use of heteroduplex mobility assays (HMA) for pre sequencing screening and identification of variant strains of avian and swine hepatitis E viruses. Vet. Microbiol. 96:165-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun, Z. F., C. T. Larsen, A. Dunlop, F. F. Huang, F. W. Pierson, T. E. Toth, and X. J. Meng. 2004. Genetic identification of an avian hepatitis E virus (HEV) from healthy chicken flocks and characterization of the capsid gene of 14 avian HEV isolates from chickens with hepatitis-splenomegaly syndrome in different geographic regions of the United States. J. Gen. Virol. 85:693-700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takahashi, M., T. Nishizawa, H. Miyajima, Y. Gotanda, T. Iita, F. Tsuda, and H. Okamoto. 2003. Swine hepatitis E virus strains in Japan form four phylogenetic clusters comparable with those of Japanese isolates of human hepatitis E virus. J. Gen. Virol. 84:851-862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tei, S., N. Kitajima, K. Takahashi, and S. Mishiro. 2003. Zoonotic transmission of hepatitis E virus from deer to human beings. Lancet 362:371-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomas, D. L., P. O. Yarbough, D. Vlahov, S. A. Tsarev, K. E. Nelson, A. J. Saah, and R. H. Purcell. 1997. Seroreactivity to hepatitis E virus in areas where the disease is not endemic. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:1244-1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsarev, S. A., T. S. Tsareva, S. U. Emerson, P. O. Yarbough, L. J. Legters, T. Moskal, and R. H. Purcell. 1994. Infectivity titration of a prototype strain of hepatitis E virus in cynomolgus monkeys. J. Med. Virol. 43:135-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van der Poel, W. H., F. Verschoor, R. van der Heide, M. I. Herrera, A. Vivo, M. Kooreman, and A. M. de Roda Husman. 2001. Hepatitis E virus sequences in swine related to sequences in humans, The Netherlands. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7:970-976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang, Y., H. Zhang, R. Ling, H. Li, and T. J. Harrison. 2000. The complete sequence of hepatitis E virus genotype 4 reveals an alternative strategy for translation of open reading frames 2 and 3. J. Gen. Virol. 81:1675-1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang, Y. C., H. Y. Zhang, N. S. Xia, G. Peng, H. Y. Lan, H. Zhuang, Y. H. Zhu, S. W. Li, K. G. Tian, W. J. Gu, J. X. Lin, X. Wu, H. M. Li, and T. J. Harrison. 2002. Prevalence, isolation, and partial sequence analysis of hepatitis E virus from domestic animals in China. J. Med. Virol. 67:516-521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williams, T. P. E., C. Kasorndorkbua, P. G. Halbur, G. Haqshenas, D. K. Guenette, T. E. Toth, and X. J. Meng. 2001. Evidence of extrahepatic sites of replication of the hepatitis E virus in a swine model. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3040-3046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu, J. C., C. M. Chen, T. Y. Chiang, W. H. Tsai, W. J. Jeng, I. J. Sheen, C. C. Lin, and X. J. Meng. 2002. Spread of hepatitis E virus among different-aged pigs: two-year survey in Taiwan. J. Med. Virol. 66:488-492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]