Abstract

Background/Aims

This study evaluated the predictors of spontaneous viral clearance (SVC), as defined by two consecutive undetectable hepatitis C virus (HCV) RNA tests performed ≥12 weeks apart, and the outcomes of acute hepatitis C (AHC) demonstrating SVC or treatment-induced viral clearance.

Methods

Thirty-two patients with AHC were followed for 12-16 weeks without administering antiviral therapy.

Results

HCV RNA was undetectable at least once in 14 of the 32 patients. SVC occurred in 12 patients (37.5%), among whom relapse occurred in 4. SVC was exhibited in 8 of the 11 patients exhibiting undetectable HCV RNA within 12 weeks. HCV RNA reappeared in three patients (including two patients with SVC) exhibiting undetectable HCV RNA after 12 weeks. SVC was more frequent in patients with low viremia than in those with high viremia (55.6% vs. 14.3%; P=0.02), and in patients with HCV genotype non-1b than in those with HCV genotype 1b (57.1% vs. 22.2%; P=0.04). SVC was more common in patients with a ≥2 log reduction of HCV RNA at 4 weeks than in those with a smaller reduction (90% vs. 9.1%, P<0.001). A sustained viral response was achieved in all patients (n=18) receiving antiviral therapy.

Conclusions

Baseline levels of HCV RNA and genotype non-1b were independent predictors for SVC. A ≥2 log reduction of HCV RNA at 4 weeks was a follow-up predictor for SVC. Undetectable HCV RNA occurring after 12 weeks was not sustained. All patients receiving antiviral therapy achieved a sustained viral response. Antiviral therapy should be initiated in patients with detectable HCV RNA at 12 weeks after the diagnosis.

Keywords: Acute hepatitis C, Spontaneous viral clearance, Interferon, HCV RNA

INTRODUCTION

World Health Organization estimates that 130 to 170 million people are chronically infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV) and at risk of developing liver cirrhosis, liver cancer, or both.1 More than 350,000 people die from HCV-related liver diseases every year. HCV is transmitted by parenteral routes, mainly contaminated blood products and other percutaneous exposures such as injection drug use, contaminated medical equipment, tattoos, acupuncture, maternal transmission, sexual contact and occupational exposure to blood products.2

Since the 1990s, the incidence of acute hepatitis C (AHC) infection has decreased because of routine screening of blood donors. Nevertheless, newly diagnosed AHC infection cases were reported at 0.3 cases per 100,000 people in US.3,4,5 Considering underestimated asymptomatic infections, the incidence of AHC infection might be higher.2

During the natural course of ACH, about 50-80% of AHC patients progressed to chronic hepatitis and remaining 20-50% of AHC patients showed spontaneous viral clearance (SVC) without treatment.6,7,8,9,10,11 Interferon-based antiviral therapy of AHC showed high rates of sustained virological response (SVR), defined by undetectable HCV RNA for 6 months after cessation of antiviral therapy,12 ranging 75-94% independent of HCV genotypes.13,14,15,16

It is important to predict the individuals who will spontaneously clear the HCV infection in order to avoid unnecessary antiviral treatment, while promptly initiating antiviral therapy to achieve high SVR for those who have a high risk for chronic hepatitis C (CHC).17

The benefit of SVR after interferon-based antiviral therapy in CHC is well-documented.18,19,20 However, little data are available if spontaneous or treatment-induced viral clearance is sustained in patients with AHC.

Therefore, this study was to analyze the predictive factors for SVC and to evaluate the outcomes in patients with spontaneous or treatment-induced viral clearance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We retropectivly analyzed 32 patients with AHC between April 2004 and December 2011. AHC was defined as (1) seroconversion from anti-HCV-negative to anti-HCV-positive with a previously negative anti-HCV test result within a year; (2) presence of HCV RNA in serum of a previous anti-HCV-negative patient.

History of exposure to possible risk factors (transfusion, invasive procedures, surgery, needle stick injury, sexual contact, tattoos, acupuncture) within 6 months before the onset of AHC was investigated by the means of a structured questionnaire at the time of first visit to each clinic.

After diagnosis of AHC was confirmed, the patients were followed at 2-4 week intervals without antiviral treatment. If SVC, defined by two consecutive undetectable HCV RNA ≥12 weeks apart, occurred, the patients were followed at 3-6 month intervals thereafter. If SVC did not occur within 12-16 weeks, we requested interferon-based antiviral therapy. In a patient whose HCV RNA progressively decreased without SVC within 3-4 months (patient 23), antiviral therapy was delayed.

The serial liver function tests, including serum albumin, bilirubin, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT), were performed using standard assays. Anti-HCV antibodies were determined at baseline and if the anti-HCV test was negative, the tests were repeated during the follow-up by using commercially available AxSYM kits (Abbott Diagnostic, Chicago, IL). Quantitative detection of HCV RNA was measured by COBAS Amplicor HCV test (Roche Molecular Systems, Pleasanton, CA; lower detection limit, 50 IU/mL) or COBAS TaqMan HCV test (Roche Molecular Diagnostics; lower detection limit, 15 IU/mL) since December 2009. HCV genotyping was performed using direct sequencing.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 12.0 (SPSS Corp, Chicago, IL, USA). The differences between the categorical variables were analyzed by a chi square test. A logistic regression analysis was used to identify independent predictive factors associated with SVC. P-values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

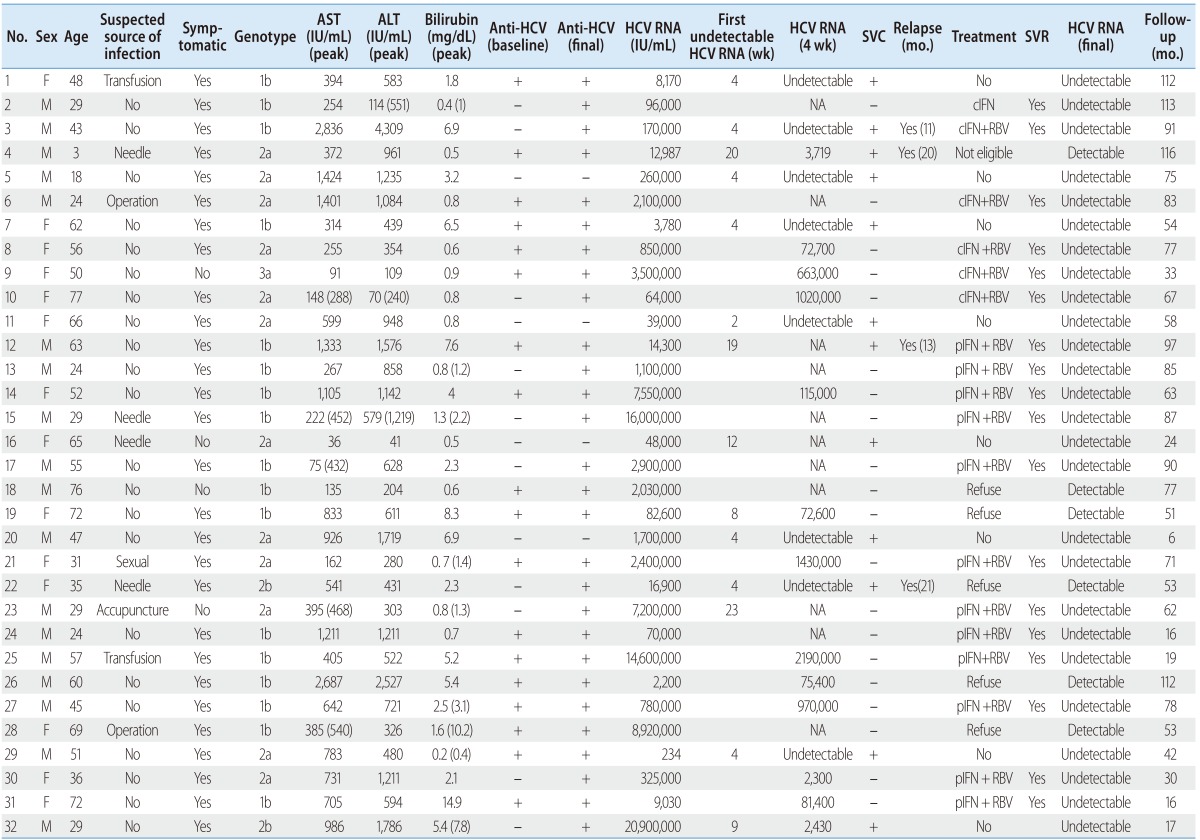

Baseline characteristics of the 32 patients are presented in Table 1 and 2. The mean age of the patients was 46.8 years (range, 3-77 years) and 18 patients (56.3%) were male. The suspected routes of AHC were as follows: occupational needle stick injury (n=4), transfusion (n=2), sexual (n=1), operation (n=2), acupuncture (n=1), and hemodialysis (n=1). However, no potential source of infection could be found in found in 21 patients (65.6%).

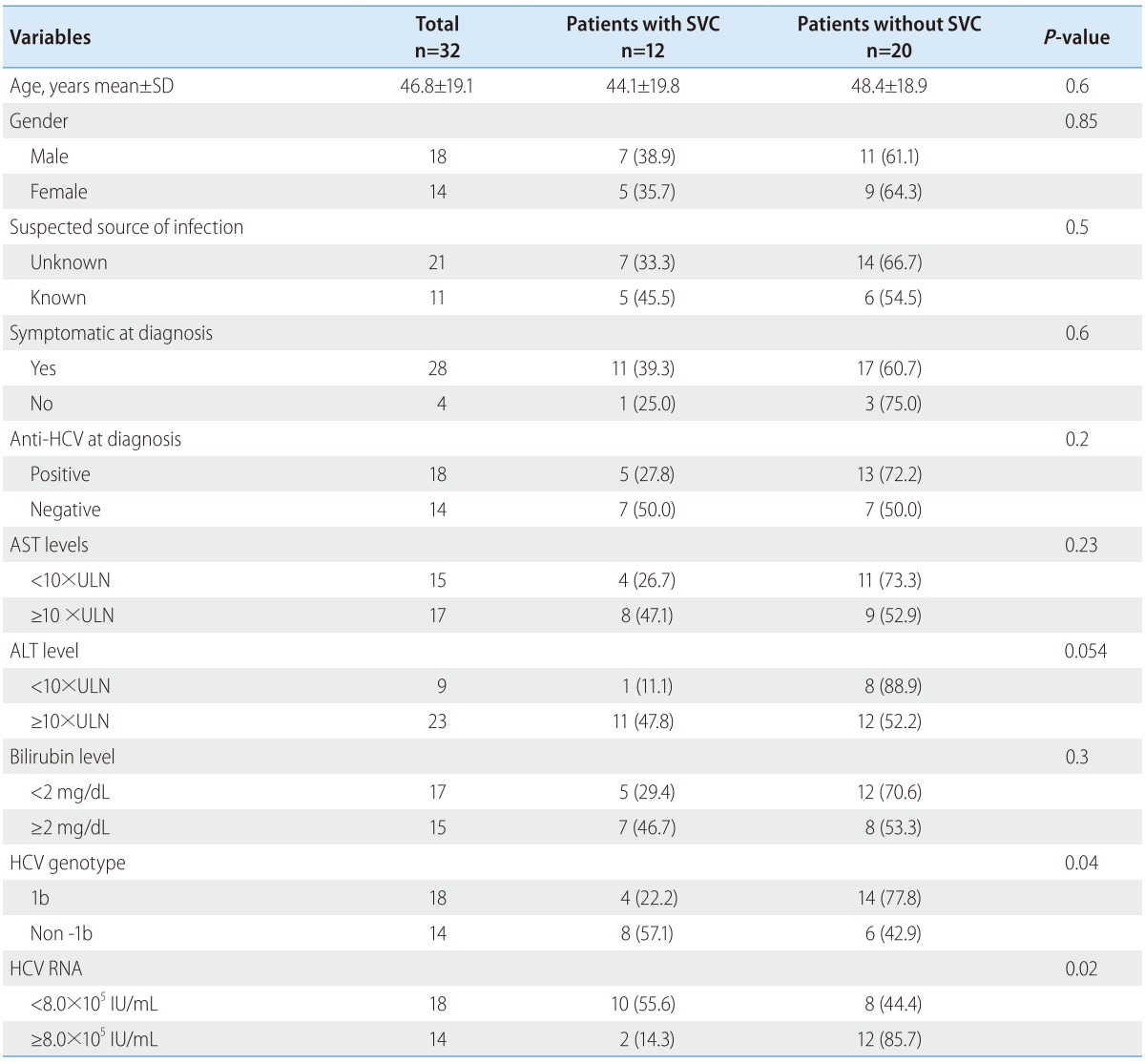

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of 32 patients with acute hepatitis C infection

SVC, spontaneous viral clearance; SD, standard deviation; AST, aspartate amionotransferase, ALT, alanine aminontransferase, ULN, upper limit normal.

Numbers in parenthesis indicate percentage.

Table 2.

Detailed clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with acute hepatitis C infection

SVC, spontaneous viral clearance; SVR, sustained virological response; cIFN, conventional interferon;RBV, ribavirin; pIFN, peginterferon; NA, not available; AST, aspartate amionotransferase, ALT, alanine aminontransferase, HCV, hepatitis C virus.

Most patients (28/32) had symptoms at the time of diagnosis. The usual symptoms of AHC were nausea, anorexia, fatigue, right upper abdominal discomfort, malaise, fever and jaundice. In 28 (88%) of the 32 patients, baseline level of ALT was elevated more than 5 times the upper limit normal (ULN). In 23 (72%) of 32 patients, ALT was elevated more than 10 times the upper limit normal (ULN) and an elevation of bilirubin (≥2 mg/dL) was observed in 15 patients at the time of diagnosis. During short-term follow-up, serum levels of ALT was elevated more than 5 times the upper limit normal in all patients except one.

Of the 32 patients with AHC, 17 (53.1%) patients were infected with genotype 1b, followed by 2a (n=12), 2b (n=2) and 3a (n=1). Fourteen patients (43.7%) were anti-HCV negative at initial clinical presentation. Among these patients, 10 patients showed anti-HCV seroconversion and the remaining 4 patients showed persistent anti-HCV negative without relapse at the end of follow-up.

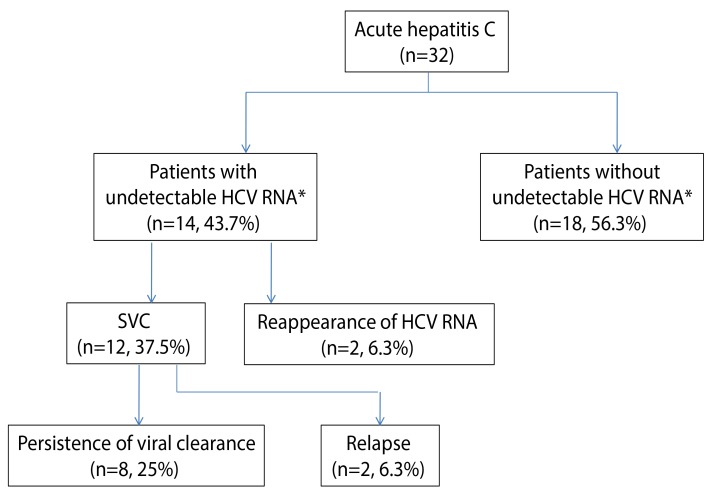

After diagnosis of AHC, the patients were followed for 6-116 months. The clinical outcomes of the patients who were followed without antiviral treatment are summarized in Figure 1 and Table 2. Undetectable HCV RNA was observed at least once in 14 patients (43.7%) during follow-up within a mean 8.8 weeks (range, 2-23 weeks). However, in 2 patients (patient 19 and 23), subsequent tests showed sustained viremia thereafter. Therefore, SVC occurred in 12 patients (37.5%). During follow-up of the patients with SVC, relapse occurred in 4 patients (patient 3, 4, 12 and 22) at 13, 20, 13 and 20 months after SVC. Among 11 patients achieving undetectable HCV RNA within 12 weeks, 8 patients showed sustained viral clearance through the follow up period. In contrast, in 3 patients (including 2 patients with SVC) who achieved undetectable HCV RNA after 12 weeks, HCV RNA reappeared or relapsed after SVC.

Figure 1.

Clinical outcomes of the patients with hepatitis C infection who were followed without antiviral treatment. *Undetectable HCV RNA at least once during follow-up. SVC, spontaneous viral clearance; HCV, hepatitis C virus.

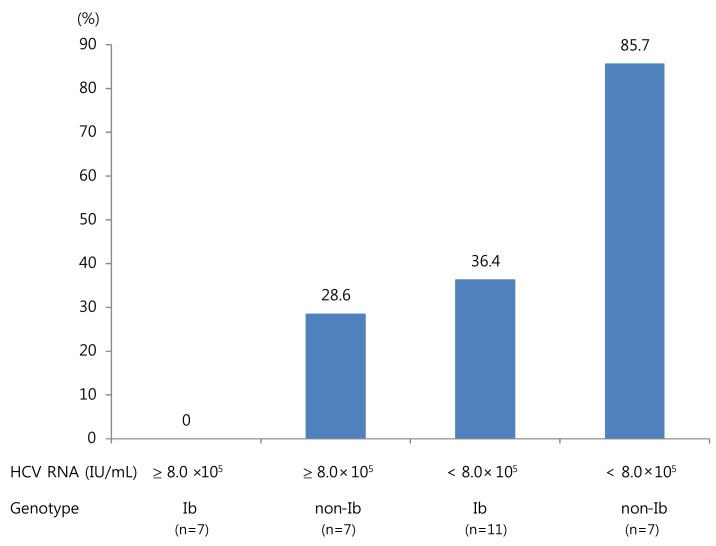

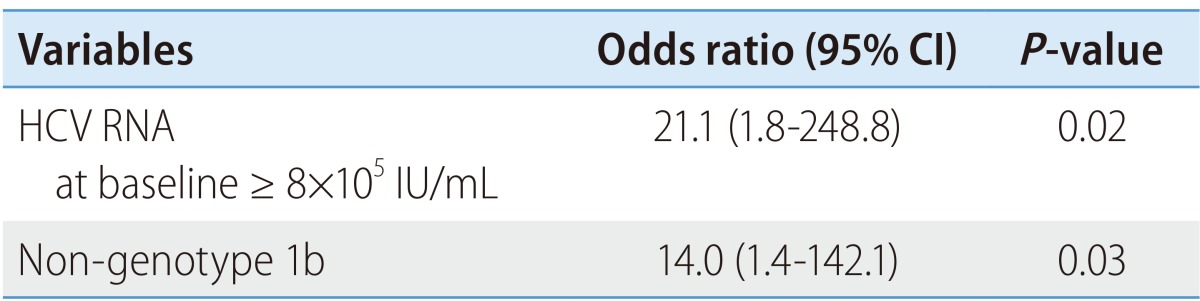

SVC was more frequent in patients with low viremia (< 8×105 IU/mL) than in those with high viremia (55.6% vs. 14.3%; P=0.02). The frequency of SVC was higher in patients with genotype non-1b compared to those with genotype 1b (57.1% vs. 22.2%; P=0.04) without any difference in the level of HCV RNA between the two groups (log10 IU/mL 5.5 vs. 5.3, P=0.9) and tended to be high in patients with high ALT (≥ 10×ULN) levels (P=0.054). However, there was no correlation between SVC and other factors, including age, gender, source of HCV infection, serum AST, status of anti-HCV, and the presence of clinical symptoms including jaundice (Table 1). In logistic regression analyses, low HCV RNA level (odds ratio 21.1; 95% confidence interval, 1.8-248.8; P=0.02) and genotype non-1b (odds ratio 14.0; 95% confidence interval, 1.4-142.1; P=0.03) were two independent predictive factors of SVC (Table 3). In AHC patients with genotype 1b and high viremia, no patients showed SVC. In contrast, in patients with genotype non-1 and low viremia, SVC occurred in 85.7% (P=0.01) (Fig. 2).

Table 3.

Baseline predictive factors for spontaneous viral clearance in patients with acute hepatitis C infection

CI; confidence interval; HCV, hepatitis C virus.

Figure 2.

Spontaneous viral clearance according to baseline levels of hepatitis C virus (HCV) RNA and HCV genotypes.

The level of serum HCV RNA at 4 weeks was available in 21 patients. The frequency of SVC was higher in patients with ≥2 log reduction of HCV RNA at 4 weeks than in those that (90% vs.9.1%, P<0001).

Interferon-based antiviral therapy commenced in 18 patients without SVC (n=16) and 2 patients with relapse after SVC (n=2, patients 3, 12) (Table 2). Five patients refused antiviral therapy (patient 18, 19, 22, 26, 28). One patient was not eligible for interferon therapy because of young age (patient 4). Patients received the antiviral regimen available at the time; interferon or peginterferon plus ribavirin combination except one (patient 2) for 24 weeks (Table 2). In most patients, antiviral therapy was initiated within 4 months of diagnosis. However, antiviral therapy was delayed over 6 months in 5 patients because of hesitance to antiviral therapy (patient 2), transient loss to follow-up (patients 6), progressively decreased HCV RNA without SVC within 3-4 months and intermittent viremia (patient 23) or relapse after SVC (patient 3, 12). All patients except one (patient 12 discontinued peginterferon plus ribavirin therapy after 2 weeks because of severe general ache) completed treatment without significant side effect. They, including patient 12, had SVR and no relapse during the follow-up period.

DISCUSSION

In this study, SVC occurred in 12 of 42 (37.5%), similar to the results of previous reports of 20-50% of AHC.6,7,8,9,10,11,21

In previous studies,6,8,21,22,23,24 undetectable HCV RNA took place within 12 weeks in most AHC patients with SVC. In this study, undetectable HCV RNA was observed at least once in 14 patients (43.7%) within a mean 8.8 weeks (range, 2-23 weeks). Nevertheless, subsequent tests showed sustained viremia in 2 patients and relapse occurred in 4 patients with SVC. Among 11 patients achieving undetectable HCV RNA within 12 weeks, 8 patients showed persistent undetectable HCV RNA at the end of follow up. In contrast, in 3 patients with undetectable HCV RNA after 12 weeks, HCV RNA reappeared or relapsed after SVC. In addition, HCV RNA persisted in 18 patients even after 12-16 weeks of follow-up. These findings indicate that a single test result showing undetectable HCV RNA may not decisively suggest spontaneous recovery from AHC and persistence of HCV RNA after 12 weeks of diagnosis might be an indicator of viral persistence. A study showed comparable SVR rate between the patients with immediate treatment and those with treatment after 12 weeks of followup (90% vs. 93%).25 Kamal et al. also reported that SVR rates were 95% and 92% who received peginterferon treatment at 8 or 12 weeks after diagnosis of AHC, respectively. In contrast, SVR rate decreased to 76% for those receiving peginterferon at 20 weeks after diagnosis.26 In addition, in the delayed interferon therapy group with observation periods of 1 year, SVR rate dropped from 100% to 53% compared with early treatment group within 8 weeks.27 In this study, SVR was achieved in all patients who received antiviral therapy if SVC did not occur within 12-16 weeks of follow-up. Therefore, if HCV RNA persists at 12 weeks of follow-up, anti-viral therapy should be initiated because there might be little chance of viral clearance without treatment and if treated at this point, SVR could be achieved in most patients.

It has been reported that Caucasian race,28 female gender,6,7,29,30 symptomatic patients including jaundice,6,23,28,31 IL28B CC genotype,7,11,32,33,34 decline in HCV-RNA9,31 and interferon γ inducible protein 10 (IP-10)11 are predictors of SVC in patients with AHC. However, the effect of HCV RNA levels and genotype on SVC is controversial.8,9,23,24,28,29,30,35,36,37,38,39 Some studies have found no association between HCV genotypes and SVC,8,9,23,28,29,30,35,36 while other studies have suggested that infection by genotype 1 or 1b might be less likely to clear spontaneously when compared with infection by other genotypes.37,38,39 In some studies, genotype I was associated with high rate of SVC7,31,40 Lewis-Ximenez et al. reported that baseline low HCV RNA levels were associated with a high chance of SVC.36 Villano et al. showed that low peak HCV RNA levels are associated with high rate of SVC.28 Two studies suggested that early HCV RNA reduction was one of the important predictors for SVC.9,31 However, other studies did not show the role of HCV RNA levels in predicting SVC.6,23,34,39

In this study, baseline HCV RNA levels and HCV genotype were two independent predictors for SVC. Dung the follow-up, reduction of HCV RNA ≥ 2 log at 4 weeks could predict SVC. High level of HCV RNA at clinical manifestation might reflect the large amount of viral inoculation (usually by blood transfusion) or inappropriate host immune clearance of HCV. The initially inoculated viral load cannot be measured practically. AHC associated with transfusion occurred in 2 patients (patient 1 with SVC, patient 25 without SVC), suggesting large amount of viral inoculation might not be likely. In addition, in all patients except one, serum ALT was eleveated over 2 times the upper limit of normal, a reflection of the immune response to HCV.41 Therefore, high HCV RNA level in spite of elevation serum ALT at clinical presentation, might reflect inappropriate immune response.

HCV genotype 1b was another important risk factor of progression to CHC in this study. The baseline levels of HCV RNA were not different between genotype 1b and non-1b. This finding suggests that some viral factors of HCV genotype 1b may contribute to progression to CHC. This hypothesis might explain in part that genotype 1 infection is the majority of CHC worldwide and commonly resist to interferon based antiviral therapy.12 HCV has the ability to disrupt and escape the host immune response during an early phase of acute infection by genetic evolution and early selection of CD8+ cytotoxic T cell escape variants.42,43,44,45 But, little data is available on HCV genotype-specific differences in immune system. Supplementary studies about immunologic response according to HCV genotype should be investigated.

We initiated antiviral therapy within 4 months in 13 patients and after 4 months in 5 patients. All patients except one were treated with a combination of interferon or peginterferon plus ribavirin. SVR was achieved in all patients. This SVR rate was very high compared with previous pooled data of 70.5% (25-97.7%).2,46 In previous studies, most patients were treated with interferon or peginterferon alone.2 The role of ribavirin combination to interferon or peginterferon are well established in CHC47,48 but not in AHC.2 In a study from Germany,6 1 of 14 patients with treated with interferon or peginterferon plus ribavirin combination showed nonresponse. In contrast, 4 of 12 patients with treated with interferon or peginterferon alone showed nonresponse or a relapse of hepatitis C after cessation of therapy. Finding of the study from Germany and our own suggested that the combination of interferon or peginterferon plus ribavirin combination might have some role in treating the patients with AHC like those with CHC.

The major limitation of this study is not to show the correlation between SVC and the IL28B genotype, which is a major host factor to predict SVC.7,11,32,33,34

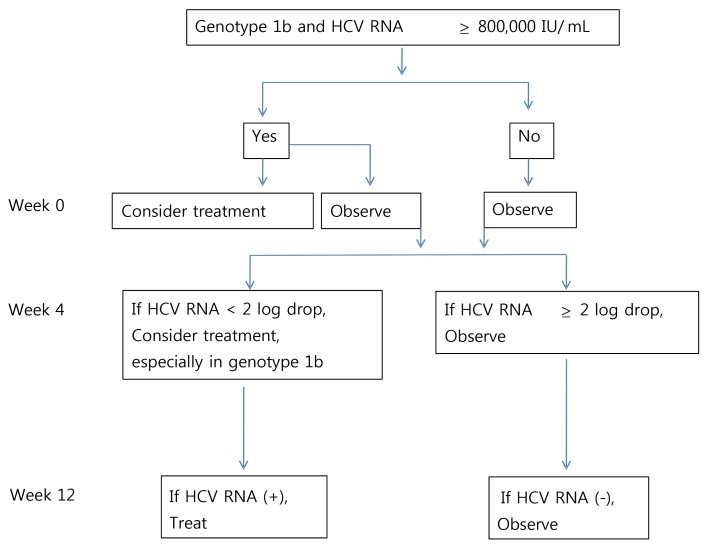

In conclusion, these data indicate that AHC with low viral load at the diagnosis and HCV genotype non-1b infection has a high chance of SVC. Reduction of HCV RNA≥2 log at 4 weeks could predict SVC. Follow-up test of HCV RNA is necessary up to 2 years because relapse may occur even after 20 months of diagnosis of AHC. In patients with detectable HCV RNA at or after 12 weeks of follow-up without treatment, antiviral therapy should be initiated because there might be little chance to have sustained viral clearance without treatment; if treated at this point, SVR could be achieved in most patients. On the basis of our data, we suggest the treatment algorithm in patients with AHC (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Suggested algorithm for the treatment of patients with acute hepatitis C infection.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the 2014 scientific promotion funded by Jeju National University.

Abbreviations

- AHC

acute hepatitis C

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- CHC

chronic hepatitis C

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- SVC

spontaneous viral clearance

- SVR

sustained viral response

- ULN

upper limit normal

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

References

- 1.WHO. Hepatitis C. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2011;86:445–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maheshwari A, Ray S, Thuluvath PJ. Acute hepatitis C. Lancet. 2008;372:321–332. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61116-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daniels D, Grytdal S, Wasley A. Surveillance for acute viral hepatitis - United States, 2007. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2009;58:1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armstrong GL, Wasley A, Simard EP, McQuillan GM, Kuhnert WL, Alter MJ. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 1999 through 2002. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:705–714. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-10-200605160-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim WR. The burden of hepatitis C in the United States. Hepatology. 2002;36:S30–S34. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.36791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerlach JT, Diepolder HM, Zachoval R, Gruener NH, Jung MC, Ulsenheimer A, et al. Acute hepatitis C: high rate of both spontaneous and treatment-induced viral clearance. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:80–88. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00668-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grebely J, Page K, Sacks-Davis R, van der Loeff MS, Rice TM, Bruneau J, et al. The effects of female sex, viral genotype, and IL28B genotype on spontaneous clearance of acute hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology. 2014;59:109–120. doi: 10.1002/hep.26639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Santantonio T, Medda E, Ferrari C, Fabris P, Cariti G, Massari M, et al. Risk factors and outcome among a large patient cohort with community-acquired acute hepatitis C in Italy. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1154–1159. doi: 10.1086/507640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beinhardt S, Payer BA, Datz C, Strasser M, Maieron A, Dorn L, et al. A diagnostic score for the prediction of spontaneous resolution of acute hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol. 2013;59:972–977. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alter MJ, Margolis HS, Krawczynski K, Judson FN, Mares A, Alexander WJ, et al. The natural history of community-acquired hepatitis C in the United States. The Sentinel Counties Chronic non-A, non-B Hepatitis Study Team. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1899–1905. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199212313272702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beinhardt S, Aberle JH, Strasser M, Dulic-Lakovic E, Maieron A, Kreil A, et al. Serum level of IP-10 increases predictive value of IL28B polymorphisms for spontaneous clearance of acute HCV infection. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:78–85. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghany MG, Strader DB, Thomas DL, Seeff LB. Diagnosis, management, and treatment of hepatitis C: an update. Hepatology. 2009;49:1335–1374. doi: 10.1002/hep.22759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wiegand J, Buggisch P, Boecher W, Zeuzem S, Gelbmann CM, Berg T, et al. Early monotherapy with pegylated interferon alpha-2b for acute hepatitis C infection: the HEP-NET acute-HCV-II study. Hepatology. 2006;43:250–256. doi: 10.1002/hep.21043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Rosa FG, Bargiacchi O, Audagnotto S, Garazzino S, Cariti G, Veronese L, et al. The early HCV RNA dynamics in patients with acute hepatitis C treated with pegylated interferon-alpha2b. Antivir Ther. 2006;11:165–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calleri G, Cariti G, Gaiottino F, De Rosa FG, Bargiacchi O, Audagnotto S, et al. A short course of pegylated interferon-alpha in acute HCV hepatitis. J Viral Hepat. 2007;14:116–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2006.00802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santantonio T, Fasano M, Sinisi E, Guastadisegni A, Casalino C, Mazzola M, et al. Efficacy of a 24-week course of PEG-interferon alpha-2b monotherapy in patients with acute hepatitis C after failure of spontaneous clearance. J Hepatol. 2005;42:329–333. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alberti A, Boccato S, Vario A, Benvegnu L. Therapy of acute hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2002;36(5 Suppl 1):S195–S200. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.36808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.George SL, Bacon BR, Brunt EM, Mihindukulasuriya KL, Hoffmann J, Di Bisceglie AM. Clinical, virologic, histologic, and biochemical outcomes after successful HCV therapy: a 5-year follow-up of 150 patients. Hepatology. 2009;49:729–738. doi: 10.1002/hep.22694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Papatheodoridis GV, Papadimitropoulos VC, Hadziyannis SJ. Effect of interferon therapy on the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with hepatitis C virus-related cirrhosis: a meta-analysis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:689–698. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.00979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shiratori Y, Imazeki F, Moriyama M, Yano M, Arakawa Y, Yokosuka O, et al. Histologic improvement of fibrosis in patients with hepatitis C who have sustained response to interferon therapy. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:517–524. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-7-200004040-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharaf Eldin N, Ismail S, Mansour H, Rekacewicz C, El-Houssinie M, El-Kafrawy S, et al. Symptomatic acute hepatitis C in Egypt: diagnosis, spontaneous viral clearance, and delayed treatment with 12 weeks of pegylated interferon alfa-2a. PLoS One. 2008;3:e4085. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giuberti T, Marin MG, Ferrari C, Marchelli S, Schianchi C, Degli Antoni AM, et al. Hepatitis C virus viremia following clinical resolution of acute hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 1994;20:666–671. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(05)80358-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Santantonio T, Sinisi E, Guastadisegni A, Casalino C, Mazzola M, Gentile A, et al. Natural course of acute hepatitis C: a long-term prospective study. Dig Liver Dis. 2003;35:104–113. doi: 10.1016/s1590-8658(03)00007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hofer H, Watkins-Riedel T, Janata O, Penner E, Holzmann H, Steindl-Munda P, et al. Spontaneous viral clearance in patients with acute hepatitis C can be predicted by repeated measurements of serum viral load. Hepatology. 2003;37:60–64. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deterding K, Grüner N, Buggisch P, Wiegand J, Galle PR, Spengler U, et al. Delayed versus immediate treatment for patients with acute hepatitis C: a randomised controlled non-inferiority trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kamal SM, Fouly AE, Kamel RR, Hockenjos B, Al Tawil A, Khalifa KE, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b therapy in acute hepatitis C: impact of onset of therapy on sustained virologic response. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:632–638. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nomura H, Sou S, Tanimoto H, Nagahama T, Kimura Y, Hayashi J, et al. Short-term interferon-alfa therapy for acute hepatitis C: a randomized controlled trial. Hepatology. 2004;39:1213–1219. doi: 10.1002/hep.20196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Villano SA, Vlahov D, Nelson KE, Cohn S, Thomas DL. Persistence of viremia and the importance of long-term follow-up after acute hepatitis C infection. Hepatology. 1999;29:908–914. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alric L, Fort M, Izopet J, Vinel JP, Bureau C, Sandre K, et al. Study of host- and virus-related factors associated with spontaneous hepatitis C virus clearance. Tissue Antigens. 2000;56:154–158. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0039.2000.560207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang CC, Krantz E, Klarquist J, Krows M, McBride L, Scott EP, et al. Acute hepatitis C in a contemporary US cohort: modes of acquisition and factors influencing viral clearance. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:1474–1482. doi: 10.1086/522608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomson EC, Fleming VM, Main J, Klenerman P, Weber J, Eliahoo J, et al. Predicting spontaneous clearance of acute hepatitis C virus in a large cohort of HIV-1-infected men. Gut. 2011;60:837–845. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.217166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu L, Fisher BE, Thomas DL, Cox AL, Ray SC. Spontaneous clearance of primary acute hepatitis C virus infection correlated with high initial viral RNA level and rapid HVR1 evolution. Hepatology. 2012;55:1684–1691. doi: 10.1002/hep.25575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tillmann HL, Thompson AJ, Patel K, Wiese M, Tenckhoff H, Nischalke HD, et al. A polymorphism near IL28B is associated with spontaneous clearance of acute hepatitis C virus and jaundice. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1586–1592. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van den Berg CH, Grady BP, Schinkel J, van de Laar T, Molenkamp R, van Houdt R, et al. Female sex and IL28B, a synergism for spontaneous viral clearance in hepatitis C virus (HCV) seroconverters from a community-based cohort. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27555. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cox AL, Netski DM, Mosbruger T, Sherman SG, Strathdee S, Ompad D, et al. Prospective evaluation of community-acquired acute-phase hepatitis C virus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:951–958. doi: 10.1086/428578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lewis-Ximenez LL, Lauer GM, Schulze Zur Wiesch J, de Sousa PS, Ginuino CF, Paranhos-Baccalá G, et al. Prospective follow-up of patients with acute hepatitis C virus infection in Brazil. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:1222–1230. doi: 10.1086/651599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lehmann M, Meyer MF, Monazahian M, Tillmann HL, Manns MP, Wedemeyer H. High rate of spontaneous clearance of acute hepatitis C virus genotype 3 infection. J Med Virol. 2004;73:387–391. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Amoroso P, Rapicetta M, Tosti ME, Mele A, Spada E, Buonocore S, et al. Correlation between virus genotype and chronicity rate in acute hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 1998;28:939–944. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(98)80340-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hwang SJ, Lee SD, Lu RH, Chu CW, Wu JC, Lai ST, et al. Hepatitis C viral genotype influences the clinical outcome of patients with acute posttransfusion hepatitis C. J Med Virol. 2001;65:505–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harris HE, Eldridge KP, Harbour S, Alexander G, Teo CG, Ramsay ME, et al. Does the clinical outcome of hepatitis C infection vary with the infecting hepatitis C virus type? J Viral Hepat. 2007;14:213–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2006.00795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rehermann B, Nascimbeni M. Immunology of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infection. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:215–229. doi: 10.1038/nri1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Farci P, Shimoda A, Coiana A, Diaz G, Peddis G, Melpolder JC, et al. The outcome of acute hepatitis C predicted by the evolution of the viral quasispecies. Science. 2000;288:339–344. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5464.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gale M, Jr, Foy EM. Evasion of intracellular host defence by hepatitis C virus. Nature. 2005;436:939–945. doi: 10.1038/nature04078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsai SL, Chen YM, Chen MH, Huang CY, Sheen IS, Yeh CT, et al. Hepatitis C virus variants circumventing cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity as a mechanism of chronicity. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:954–965. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70268-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bowen DG, Walker CM. Adaptive immune responses in acute and chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Nature. 2005;436:946–952. doi: 10.1038/nature04079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Licata A, Di Bona D, Schepis F, Shahied L, Craxi A, Camma C. When and how to treat acute hepatitis C? J Hepatol. 2003;39:1056–1062. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(03)00461-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fried MW, Shiffman ML, Reddy KR, Smith C, Marinos G, Gonçales FL, Jr, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:975–982. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hadziyannis SJ, Sette H, Jr, Morgan TR, Balan V, Diago M, Marcellin P, et al. Peginterferon-alpha2a and ribavirin combination therapy in chronic hepatitis C: a randomized study of treatment duration and ribavirin dose. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:346–355. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-5-200403020-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]