Abstract

Reversible focal lesions on the splenium of the corpus callosum (SCC) have been reported in patients with mild encephalitis/encephalopathy caused by various infectious agents, such as influenza, mumps, adenovirus, Varicella zoster, Escherichia coli, Legionella pneumophila, and Staphylococcus aureus. We report a case of a reversible SCC lesion causing reversible encephalopathy in nonfulminant hepatitis A. A 30-year-old healthy male with dysarthria and fever was admitted to our hospital. After admission his mental status became confused, and so we performed electroencephalography (EEG) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain, which revealed an intensified signal on diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) at the SCC. His mental status improved 5 days after admission, and the SCC lesion had completely disappeared 15 days after admission.

Keywords: Acute hepatitis A, Encephalopathy, Magnetic resonance imaging, Corpus callosum

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis A virus (HAV) infection usually occurs through fecal-oral transmission by either direct contact with an infected person or the ingestion of food or water contaminated with HAV.1 HAV infection in early childhood is usually asymptomatic or only mildly symptomatic.2 The relative frequency of symptomatic and asymptomatic HAV infections has been reasonably well characterized and is age- dependent.2,3 Improved hygiene and sanitary conditions have significantly reduced childhood exposure to HAV. As a result, a gradual shift has developed in the age of infection from early childhood to adulthood. This change has led to an increase in symptomatic cases and severe clinical outcomes including hepatic failure.2 Atypical manifestations include relapsing hepatitis, prolonged cholestasis, and complicated cases with acute kidney injury.4 Extrahepatic manifestations, such as autoimmune hemolytic anemia, aplastic anemia, pure red cell aplasia, pleural or pericardial effusion, acute reactive arthritis, acute pancreatitis, acalculous cholecystitis, mononeuritis, and Guillain-Barre syndrome, have been reported.4 However, there is no report of a reversible splenial lesion detected by brain MRI presenting as encephalopathy in a patient with an HAV infection. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a non-fulminant hepatitis A patient presenting with encephalopathy associated with a reversible splenial lesion detected by brain MRI.

CASE REPORT

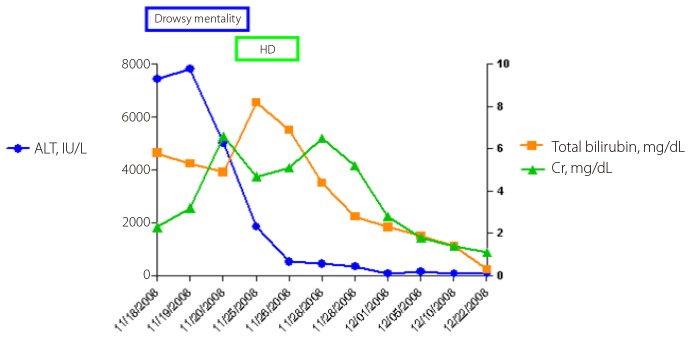

A 30-year-old healthy male was admitted with dysarthria after a 4-day prodromal illness consisting of fever. There was no history of alcoholism or drug abuse. Upon admission, the laboratory findings were as follows; white blood cell count of 3,480/µL, platelet count of 89,000/µL, prothrombin time internal normalized ratio (INR) of 1.44, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) level of 18,440 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level of 7,450 IU/L, total bilirubin of 5.8 mg/dL, albumin of 4.4 g/dL, creatinine of 2.3 mg/dL, ammonia of 50 µg/dL, sodium of 138 mmol/L, potassium of 3.8 mmol/L, chloride of 114 mmol/L, and calcium of 8.3 mg/dL. The patient tested negative for hepatitis B and C and positive for an IgM antibody against HAV (Fig.1). Abdominal sonography showed a mild fatty liver, gallbladder collapse, and wall edema. On day 3 after admission, we performed EEG and an MRI of the brain because of the patient's persistent confused mental status despite an improvement in liver function (Fig.2). The EEG showed abnormal II (deep drowsy), continuous low-amplitude electrical activity, a moderate amount of theta-to-delta slow activity, and no epileptiform discharge. Brain MRI revealed hyperintensity on DWI in the splenium of the corpus callosum (SCC). On day 3, the patient underwent hemodialysis because of aggravated azotemia, oliguria, and pulmonary edema. On day 4, his mental status, except for dysarthria, was improved. On day 5, his dysarthria resolved. On day 12 after admission, hemodialysis was stopped, and the lesion on the SCC completely disappeared 15 days after admission (Fig.2).

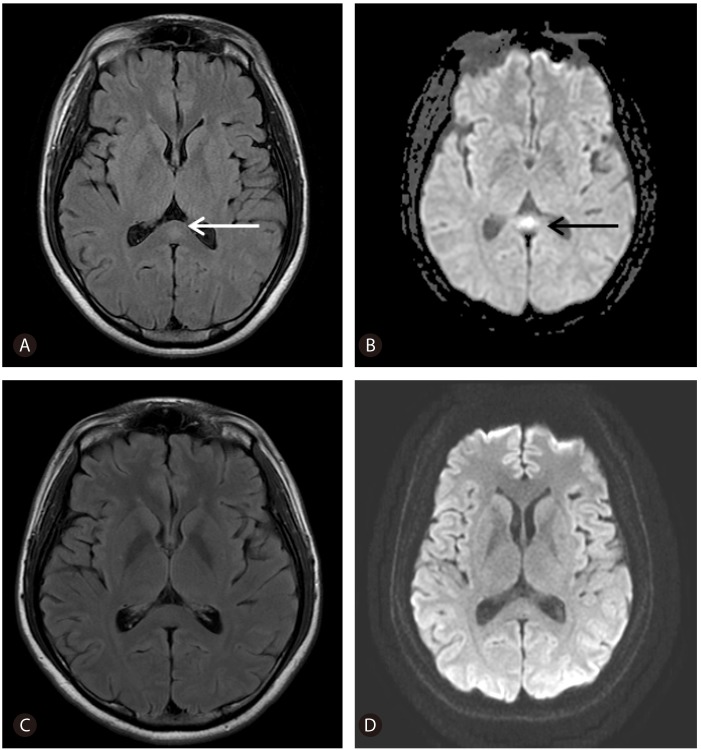

Figure 1.

Clinical course in a 30-year-old male patient with non-fulminant hepatitis A. HD, hemodialysis; Cr, creatinine; ALT, alanine aminotransferase.

Figure 2.

Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) (A) and axial magnetic diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) on day 3 of hospitalization, and FLAIR (C) and DWI (D) 15 days after admission. The arrows indicate a small, round lesion on the splenium of the corpus callosum.

DISCUSSION

Acute hepatitis A shows more severe clinical manifestations in adults than in children. The management of acute hepatitis A includes general supportive care and critical decisions regarding liver transplantation.4 A reversible lesion on the SCC was first reported in patients receiving antiepileptic drugs and, more recently, in children with clinically mild encephalitis/encephalopathy caused by various infectious agents, such as influenza, mumps, adenovirus, Varicella zoster, Escherichia coli, Legionella pneumophila, and Staphylococcus aureus.5,6,7,8,9 By brain MRI, the lesions are hyperintense on T2-weighted imaging and iso-hypointense on T1-weighted imaging with no contrast enhancement.10 On diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), the lesions are hyperintense, with low apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values, reflecting restricted diffusion due to cytotoxic edema.10 The common feature is the disappearance of imaging abnormalities over time, with clinical improvement. All of the reported cases of encephalitis/encephalopathy present with neurologic signs, many of which involve seizures or mildly altered states of consciousness, such as drowsiness.5,7 Although the pathophysiology of these lesions is unknown, reversible excitotoxic edema and inflammatory infiltrates were implicated in patients with encephalitis/encephalopathy.5,7 An association between hyponatremia and reversible splenial lesions was reported by Takanashi et al. in patients with clinically mild encephalitis/encephalopathy.9

Reversible lesions on the SCC have been found under the several different conditions, such as seizures, antiepileptic drug toxicity, antiepileptic drug treatment, viral encephalitis, hypoglycaemia, Wernicke encephalopathy, hemolytic uremic syndrome, altitude brain injury, and acute axonal injury.10 Edema and diffusion restriction in a reversible lesion on the SCC has been attributed to excitotoxic mechanisms without brain ischemia.10 It is not clear why this reversible excitotoxic edema selectively involves the SCC.10 The only explanation for the reversible focal lesion on the SCC, detected by brain MRI, would be a selective vulnerability of the SCC to various causes of excitotoxic injury.10

Common causes of metabolic encephalopathy are drugs and toxins, such as, alcohol, sedatives, antidepressants, and antiepileptic drugs; infection including CNS infection; electrolyte disturbances; hypoglycemia; and thyrotoxicosis.11 Frequent causes of reversible focal lesions on the SCC are viral encephalitis, antiepileptic drug toxicity or withdrawal and hypoglycemic encephalopathy.10 Therefore, it may be useful to consider these conditions in the patients with changes in their consciousness and in their SCC, as detected by brain MRI.

Brain MRI may be useful to exclude organic CNS diseases, such as stoke, tumor, or abscess. Brain MRI is superior to CT for the diagnosis of brain edema in patients with hepatic encephalopathy but is not an established modality for the diagnosis of hepatic encephalopathy. EEG is useful in patients with altered consciousness to exclude seizure disorders. Triphasic waves are associated with hepatic encephalopathy and severe metabolic disturbances including uremic and septic encephalopathy. The diagnosis of hepatic encephalopathy could be performed after the exclusion of unrelated neurologic and/or metabolic causes of encephalopathy.11 Imaging modalities including CT, MRI, and EEG may be necessary to exclude other causes of encephalopathy.

There is no previous report of a reversible splenial lesion detected by brain MRI presenting with encephalopathy in non-fulminant hepatitis A patients.

In conclusion, we describe a non-fulminant hepatitis A patient presenting with encephalopathy, which may have been related to a reversible focal lesion on the SCC. DWI may offer the best image of a splenial abnormality in a hepatitis A-infected patient with changes in consciousness.

Abbreviations

- EEG

electroencephalography

- DWI

diffusion-weighted imaging

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

References

- 1.Fiore AE. Hepatitis A transmitted by food. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:705–715. doi: 10.1086/381671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim YJ, Lee HS. Increasing incidence of hepatitis A in Korean adults. Intervirology. 2010;53:10–14. doi: 10.1159/000252778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hadler SC, Webster HM, Erben JJ, Swanson JE, Maynard JE. Hepatitis A in day-care centers. A community-wide assessment. N Engl J Med. 1980;2:1222–1227. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198005293022203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jeong SH, Lee HS. Hepatitis A: clinical manifestations and management. Intervirology. 2010;53:15–19. doi: 10.1159/000252779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsuji M, Yoshida T, Miyakoshi C, Haruta T. Is a reversible splenial lesion a sign of encephalopathy? Pediatr Neurol. 2009;41:143–145. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2009.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim SS, Chang KH, Kim ST, Suh DC, Cheon JE, Jeong SW, et al. Focal lesion in the splenium of the corpus callosum in epileptic patients: antiepileptic drug toxicity? Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20:125–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tada H, Takanashi J, Barkovich AJ, Oba H, Maeda M, Tsukahaha H, et al. Clinically mild encephalitis/encephalopathy with a reversible splenial lesion. Neurology. 2004;63:1854–1858. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000144274.12174.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takanashi J, Barkovich AJ, Yamaguchi K, Kohno Y. Influenza-associated encephalitis/ encephalopathy with a reversible lesion in the splenium of the corpus callosum: a case report and literature review. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25:798–802. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takanashi J, Tada H, Maeda M, Suzuki M, Terada H, Barkovich AJ. Encephalopathy with a reversible splenial lesion is associated with hyponatremia. Brain Dev. 2009;31:217–220. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gallucci M, Limbucci N, Paonessa A, Caranci F. Reversible focal splenial lesions. Neuroradiology. 2007;49:541–544. doi: 10.1007/s00234-007-0235-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bleibel W, Al-Osaimi AM. Hepatic encephalopathy. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:301–309. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.101123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]