Abstract

A Taqman amplicon targeting the nucleocapsid gene of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) is 5 log10 times more sensitive for SARS-CoV target RNA extracted from infected cells and 2.79 log10 times more sensitive for RNA extracted from patient material of the index case in Frankfurt than an amplicon targeting the polymerase gene.

The severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic, originating in Guangdong in southern China, caused 8,096 reported cases and 774 deaths in 30 countries in 2003 (World Health Organization, http://www.who.int/Csr/sars/country/table2004_04_21/en/, 2003). SARS is considered to be the first serious emergent disease of the 21st century. It was found to be caused by a previously unknown lineage of coronavirus (SARS-CoV) (1, 4), most likely of zoonotic origin. The SARS-CoV genome is about 30 kb long. Differential transcription of its genes generates a gradient of subgenomic RNAs (sgRNA) with a common 3′ end (2, 4-6). This implies that genes at the 3′ end should be transcribed at high levels and that sgRNA species produced by transcription of these genes might be the most abundant during cell infection. The genomic organization of the coronavirus, with the nonstructural genes placed at the 5′ end and structural genes placed at the 3′ end, may reflect this transcription strategy. For example, the products of nonstructural genes, such as the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (Pol), responsible for replication and transcription of the viral genome, are needed in smaller amounts than those from structural genes, such as the nucleocapsid protein (NC), involved in assembly of the virions. Hence there may be higher levels of sgRNA from structural genes than from nonstructural genes.

This feature of coronavirus biology may be relevant for improving its detection in diagnostics. Most RNA viruses can be detected only during the acute initial phase of the disease, on the first few days after disease onset. However, during the early symptomatic phase of SARS only low levels of SARS-CoV have been found. Viral detection in stools and respiratory material eventually peaks at around 10 days after the onset of clinical symptoms, well after virus could be transmitted to other susceptible hosts (1). Therefore, the early detection of SARS-CoV genetic material is crucial for improving SARS control, since patients are able to transmit the virus before it can be detected.

To optimize SARS-CoV detection, we designed a Taqman reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) amplicon targeting the NC gene of SARS-CoV. We used the consensus sequence of the NC gene obtained from an alignment of 17 available complete genome sequences of the SARS-CoV to search for an optimal amplicon with the Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems). We found an optimal Taqman RT amplicon (NC amplicon) amplified by primers NCCORFP (5′-TGCCTCTGCATTCTTTGGA-3′) and NCCORRP (5′-TAAGTCAGCCATGTTCCCG-3′) and the Taqman probe NCCORP (6-carboxyfluorescein-5′-CACGCATTGGCATGGAAGTCACA-3′-6-carboxy tetramethylrhodamine), hybridizing from nucleotides 29054 to 29122 of the total SARS-CoV sequence (GenBank accession no. AY278741). These NC primers and the Pol gene primers (TMSARS1, TNSARAs2, and TMSARSP1), published by Drosten et al. (1), were compared in end point titrations on a 10-fold dilution range of CoV-RNA extracted from Vero E6 cell culture lysate. They were also tested on fivefold dilution ranges of RNA extracted from stool and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) of the index patient from Frankfurt, Germany. Taqman RT-PCR for the Pol assay was performed as described previously (1); the NC assay was performed in 20 μl as follows: 61°C for 20 min, 95°C for 5 min, and 45 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 30 s using the LightCycler RNA Master Hybridization Probes kit (Roche). Cloning of amplicons and RNA transcription were performed as described in reference 7. Cell culture of the SARS-CoV was done as described in reference 1. RNA was extracted from infected Vero E6 cells after 24 h by Trizol extraction (Invitrogen) and from patient material with the Qiamp viral RNA kit (QIAGEN).

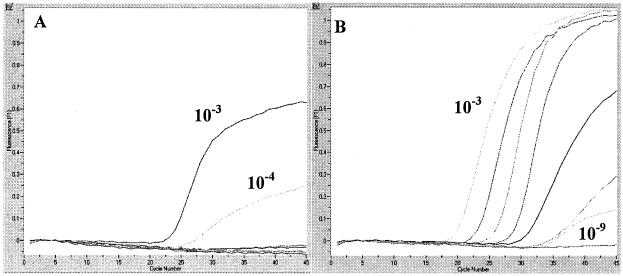

To compare the sensitivities of both assays, we cloned each target amplicon into a plasmid and transcribed RNA, which was quantified and diluted into an RNA standard range (109 to 101 RNA molecules). When used to test the respective RNA standards, both the Pol and NC assays had a sensitivity of 104 copies detected (standard correlations [r] = 0.97 and 1, respectively; efficiencies = 0.58 and 1.18, respectively). We determined the limit of detection (LOD) in RNA extracted from cell culture. The Pol assay detected viral RNA down to a dilution of 1:105, whereas the NC assay was sensitive down to a dilution of 1:109 (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Both assays were negative on RNA extracted from uninfected cells. In the RNA extracted from stool, the Pol and NC assays detected viral RNA down to dilutions of 1:5 and 1:3,125, respectively. In the RNA extracted from BALF the Pol and NC assays detected viral RNA down to dilutions of 1:25 and 1:15,625, respectively. In comparison to the Pol assay, the NC assay detected viral RNA at a sensitivity 625 times higher in both patient materials. Both assays were fivefold more sensitive to the RNA extracted from BALF than to the RNA extracted from stool, which may be due to stool inhibitors. The numbers of copies detected at the LOD by the Pol assay were 1.28 × 104 in the cell culture sample, 6.2 × 108/ml of stool, and 4.9 × 108/ml of BALF. The numbers of copies detected at the LOD by the NC assay were 1.28 ×104 in the cell culture sample, 3.46 × 108/ml of stool, and 2.89 × 105/ml of BALF.

FIG. 1.

Real-time RT-PCR fluorescence plots. Both the Pol assay (left) and the NC assay (right) used a range of 10-fold dilutions, from 10−3 to 10−9, of RNA extracted from Vero E6 cells. The Pol assay detected RNA in the 10−3 and 10−4 dilutions, whereas the NC assay detected RNA in 10−3 to 10−9 dilutions, possibly because sgRNA molecules produced by transcription of the NC gene are more abundant in infected cells than those produced by transcription of the Pol gene.

TABLE 1.

End point titrations of SARS-CoV RNA for the Pol and NC assays

| Sample | Assay | Mean CPa at a dilution factor of:

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 103 | 104 | 105 | 106 | 107 | 108 | 109 | 5 | 25 | 125 | 625 | 3,125 | 15,625 | ||

| Vero E6 cell culture | Pol | 25.32 ± 0.46 | 28.25 ± 0.68 | —b | — | — | — | — | ||||||

| NC | 19.94 ± 0.55 | 23.57 ± 0.9 | 26.73 ± 0.7 | 29.88 ± 0.8 | 32.17 ± 0.31 | 36.41 ± 1.34 | 39.41 ± 1.59 | |||||||

| Stool | Pol | 26.22 | — | — | — | — | — | |||||||

| NC | 28.77 | 29.96 | 32.58 | 34.06 | 35.17 | — | ||||||||

| BALF | Pol | 26.97 | 32.44 | — | — | — | — | |||||||

| NC | 26.80 | 29.91 | 31.48 | 33.35 | 34.80 | 36.34 | ||||||||

CP, the point at which the fluorescence signal crosses a threshold of 0.1 fluorescence intensity unit (LightCycler software). The mean CP was calculated from data sets of three independent LightCycler runs.

—, no RNA detected.

Since both assays have about the same sensitivity, comparing the LOD end points of both assays suggests a Pol sgRNA/NC sgRNA ratio of 1:104 in cell culture RNA and a ratio of 1:6.25 × 102 in patient sample RNA. These ratios are most likely due to the differential abundances of their respective target sgRNA molecules and therefore indeed reflect the transcriptional gradient of sgRNA molecules from the 3′ end to the 5′ end produced at the highest level in a fully infected cell culture and at lower levels in cells from infected patients. The difference in these sgRNA ratios may be due to less-efficient and even abortive virus replication in human tissue compared to full-blown replication in an infected monolayer of a Vero E6 cell culture.

The implication for diagnostic testing is that the current RT-PCR assays targeting the Pol gene detect SARS-CoV less efficiently and less sensitively than is possible when targeting the NC gene. The larger amount of NC sgRNA in cells observed here may mean that a stronger signal could be picked up from patient samples containing cells sooner than is currently feasible with the Pol assay, which is in widespread use due to its early introduction soon after the first SARS cases hit Europe and the Americas. As a consequence of our data we suggest that PCR assays targeting the NC gene should be considered a valuable alternative for SARS-CorV diagnostics, especially as only 40 to 50% of patients tested in days 1 to 6 after onset of disease are positive by RT-PCR (J. S. Peiris, http://www.who.int/csr/sars/conference/june_2003/materials/presentations/en/aetiology.pdf, 2003).

Acknowledgments

We thank the Hoffmann La-Roche Foundation for supporting this work.

We thank Otto Haller for critically reading the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Drosten, C., S. Gunther, W. Preiser, S. van der Werf, H. R. Brodt, S. Becker, H. Rabenau, M. Panning, L. Kolesnikova, R. A. Fouchier, A. Berger, A. M. Burguiere, J. Cinatl, M. Eickmann, N. Escriou, K. Grywna, S. Kramme, J. C. Manuguerra, S. Muller, V. Rickerts, M. Sturmer, S. Vieth, H. D. Klenk, A. D. Osterhaus, H. Schmitz, and H. W. Doerr. 2003. Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 348:1967-1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mizutani, T., J. F. Repass, and S. Makino. 2000. Nascent synthesis of leader sequence-containing subgenomic mRNAs in coronavirus genome-length replicative intermediate RNA. Virology 275:238-243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peiris, J. S., C. M. Chu, V. C. Cheng, K. S. Chan, I. F. Hung, L. L. Poon, K. I. Law, B. S. Tang, T. Y. Hon, C. S. Chan, K. H. Chan, J. S. Ng, B. J. Zheng, W. L. Ng, R. W. Lai, Y. Guan, and K. Y. Yuen. 2003. Clinical progression and viral load in a community outbreak of coronavirus-associated SARS pneumonia: a prospective study. Lancet 361:1767-1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rota, P. A., M. S. Oberste, S. S. Monroe, W. A. Nix, R. Campagnoli, J. P. Icenogle, S. Penaranda, B. Bankamp, K. Maher, M. H. Chen, S. Tong, A. Tamin, L. Lowe, M. Frace, J. L. DeRisi, Q. Chen, D. Wang, D. D. Erdman, T. C. Peret, C. Burns, T. G. Ksiazek, P. E. Rollin, A. Sanchez, S. Liffick, B. Holloway, J. Limor, K. McCaustland, M. Olsen-Rasmussen, R. Fouchier, S. Gunther, A. D. Osterhaus, C. Drosten, M. A. Pallansch, L. J. Anderson, and W. J. Bellini. 2003. Characterization of a novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Science 300:1394-1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sawicki, S. G., and D. L. Sawicki. 1998. A new model for coronavirus transcription. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 440:215-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Snijder, E. J., P. J. Bredenbeek, J. C. Dobbe, V. Thiel, J. Ziebuhr, L. L. Poon, Y. Guan, M. Rozanov, W. J. Spaan, and A. E. Gorbalenya. 2003. Unique and conserved features of genome and proteome of SARS-coronavirus, an early split-off from the coronavirus group 2 lineage. J. Mol. Biol. 331:991-1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weidmann, M., V. Rudaz, M. R. Nunes, P. F. Vasconcelos, and F. T. Hufert. 2003. Rapid detection of human pathogenic orthobunyaviruses. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:3299-3305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]