Abstract

Considerable amount of money spent in health care is used for treatments of lifestyle related, chronic health conditions, which come from behaviors that contribute to morbidity and mortality of the population. Back and neck pain are two of the most common musculoskeletal problems in modern society that have significant cost in health care. Yoga, as a branch of complementary alternative medicine, has emerged and is showing to be an effective treatment against nonspecific spinal pain. Recent studies have shown positive outcome of yoga in general on reducing pain and functional disability of the spine. The objective of this study is to conduct a systematic review of the existing research within Iyengar yoga method and its effectiveness on relieving back and neck pain (defined as spinal pain). Database research form the following sources (Cochrane library, NCBI PubMed, the Clinical Trial Registry of the Indian Council of Medical Research, Google Scholar, EMBASE, CINAHL, and PsychINFO) demonstrated inclusion and exclusion criteria that selected only Iyengar yoga interventions, which in turn, identified six randomized control trials dedicated to compare the effectiveness of yoga for back and neck pain versus other care. The difference between the groups on the postintervention pain or functional disability intensity assessment was, in all six studies, favoring the yoga group, which projected a decrease in back and neck pain. Overall six studies with 570 patients showed, that Iyengar yoga is an effective means for both back and neck pain in comparison to control groups. This systematic review found strong evidence for short-term effectiveness, but little evidence for long-term effectiveness of yoga for chronic spine pain in the patient-centered outcomes.

Keywords: Back pain, complementary alternative medicine, effectiveness, Iyengar yoga, neck pain, randomized control trials, spine pain

INTRODUCTION

Significant amount of money spent in today's health care environment is used for treatments of chronic health conditions. These include back and neck pain, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, obesity, and cancer.[1] These lifestyle related conditions are usually the result of the stubborn behaviors, which immensely contribute to morbidity and mortality of the population, such as: Lack of physical activity[2,3,4] overeating and improper diet,[5,6] cigarette smoking,[7,8] excessive alcohol consumption,[9,10] socioeconomic stress and inability to cope, poor mental health,[11] low social support,[12,13] poor sleep,[14] etc.

Chronic pain in the spine (nonspecified) is a musculoskeletal disorder with public health and economic impact. Back and neck pain are two of the most common musculoskeletal problems in modern society[15] causing considerable costs in health care. Low back pain is common and poses a challenge for clinicians to devise effective, preventive treatment from becoming chronic. Research shows that spinal pain has become the largest category of medical claims, placing a major burden on individuals and health care system.[16]

What could bring positive changes into the health behaviors as a noninvasive, nonsurgical and nondrug method of treatment, which would reduce this ailment? Extensive research points to the subject of yoga that is proposed to be an effective solution. A carefully adapted set of yoga poses can help reduce pain and improve functional (the ability to walk and move).

Among different variations of yoga, we will review the beneficial effects on pain treatment through Iyengar yoga. Iyengar yoga is a form of Hatha yoga that puts the focus on detail, precision and alignment in the performance of posture (asana) and breath control (pranayama). The development of strength (stamina), mobility and stability is gained through the asanas. Iyengar yoga is considered to be therapeutic, quasi medical yoga and more effective for many treatments (pain syndromes, cardiovascular diseases, pulmonary and respiratory diseases, distress, depression, hormonal and endocrine disorders, gynecological, gastroenterological diseases, arthritis, etc.). The Iyengar method uses supportive props and strictly designed sequences of postures to address an individual's medical issues. The general concept regarding a sequence of yoga poses predetermines that poses should not irritate the nervous system; there should be strict order of practicing (given that some asanas produce heat, stimulate, energize, activate, others produce coolness, abate, relax, etc.), appropriate preparation for inversions and backward extension. Sequencing, timing and intricacy of poses in Iyengar method provide a framework to structure the progression and content of therapy.[17]

The etiology of back pain is not fully researched and understood; however, the psychological, psychosocial/occupational and physical factors are considered as strong causative factors.[18] In a small number of cases, back/neck pain is caused by a specific medical condition that is, whiplash, shoulder pain, frozen shoulder, ankylosing spondylitis, slipped disc, sciatica, etc.

Spinal pain (usually low back and neck pain) is the condition for which often complementary therapies are being used.[19] Despite the ubiquity of back pain, it is one of the conditions that modern medicine does not treat well, partly due to imprecision of diagnosis and relative ineffectiveness of most conventional treatments. Although yoga may have the potential to ameliorate both chronic and acute pain in general, the mechanisms by which this is effected remain hypothetical.[19] Nevertheless, today, yoga is quite commonly used as complementary treatment for spinal pain.[20] S. Duke, D.C., a sports chiropractor in New York city, points out that doctors today are looking for ways where patients can be more aware and be proactive participants in taking care of their own back pain, versus being treated.[21] Although there is not one-single treatment that is universal for every condition, many aspects and techniques of yoga make it an ultimate method for treating back and neck pain by gaining strength, flexibility and endurance, which is a basic goal of most rehabilitation programs for back or neck pain.

Much has been studied through randomized control trials (RCT) regarding yoga in general, but only few studies have been dedicated so far to the therapeutic benefits of Iyengar yoga in particular. The purpose of this systematic review is to present the evidence of the effectiveness of Iyengar yoga method as a therapy for treating back and neck pain based on findings of RCT.

METHODOLOGY

Protocol and method

This review protocol is based on the PRISMA guidelines and checklist consisting of 27 items for reporting a systematic review and meta-analyses[22] adopting terminology of Cochrane Collaboration.[23] The goal of the literature search is to be exhaustive enough to develop a comprehensive list of potentially relevant studies. All of the studies included in the systematic review come from this list.[24]

Information sources

The literature search was performed using the following electronic databases: Cochrane library, NCBI PubMed, the Clinical Trial Registry of the Indian Council of Medical Research, Google Scholar, EMBASE, CINAHL, and PsychINFO.

Search

The search terms used contained: Iyengar yoga OR yoga and back pain OR neck pain and RCT.

Study selection and data items

After identifying studies from electronic databases, the bibliographies of the review articles in the field were also searched and reviewed to identify additional relevant studies. Hard copies of included studies - RCT assessing effectiveness of Iyengar yoga intervention on back or neck pain in adult population with preexisiting back or neck pain compared with the control group - were read and analyzed in full.

Data collection process

For each study, the data were extracted: Trial design, randomization, blinding, drop-out rate, and inclusion and exclusion criteria, details of treatment method and comparison group, main outcome measures, main findings.

Summary measures analyses

As far as summary measure, this review was limited to the studies looking at the mean change of pain after intervention and follow-up for each outcome compared with baseline, which was defined as the primary outcome measure and was used to assess the differences between the yoga and control groups.

Risk of bias within studies

The assessment of bias risks has been performed based on the Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias. The summary template of criteria for judging risk of bias, including selection bias (random allocation and allocation concealment), performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, reporting, and other possible bias was used. Trial co-writers were contacted for two studies (Tilbrook et al. 2011 and Cox et al. 2010 where further clarifications were necessary. Discrepancies of the review were resolved through a second independent reviewer. Trials that met at least 50% (four out of eight) criteria and had no serious flaw were rated as high quality studies with low risk of bias. Trials that met less than half of the criteria or had serious flaws were marked as having high-risk of bias.[23]

RESULTS

Selection of studies

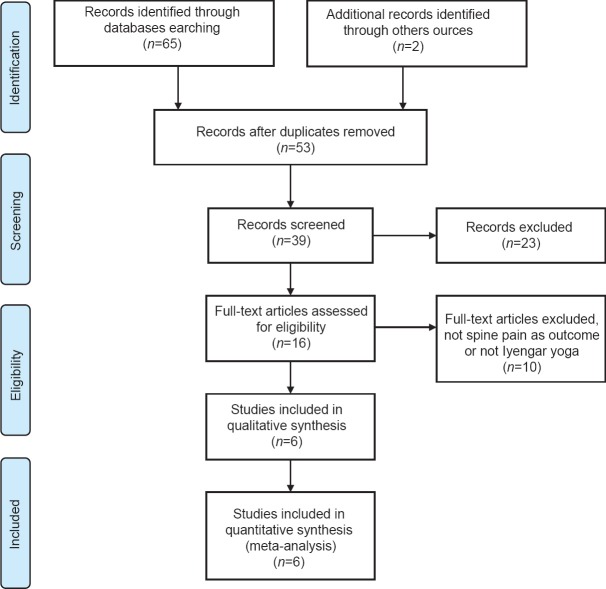

The search strategy generated a total of 65 articles through electronic database and bibliography articles, which, after removing duplicates, resulted in 53 retrieved studies that focused on treating back or neck pain being managed by yoga practice. Along with RCT and pilot trials, these papers also included case studies, observational studies, and uncontrolled trials. However, for the sake of validity of this review, only RCT studying the effects of Iyengar yoga (six studies) were taken into consideration for further analyses. The population under research is the adult population with preexisting condition of neck or back pain for minimum 3 months preceding intervention, comparing yoga group with other treatment group.

Study inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies meeting the following criteria were considered for review (inclusion criteria):

Study participants were adults from 18 to 67 years of age

Study participants having preexisting diagnosis of back or neck pain preliminary screened and reported by the physicians (with average duration of symptoms over 3 months before the start of the study or a minimum score of pain of >30 mm on 100 mm visual analog scale [VAS])

Study measuring pain intensity of back or neck, respectively used pain outcome (VAS) or functional disability outcome measures (Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire [RMDQ]) in pre- and post-intervention and evaluated the outcome based on the reduction on back/neck pain

Presence of the two groups in the study with symptoms of back or neck pain: Randomly assigned persons who were not ardent practitioners of Iyengar yoga either to the yoga practicing group or to the control group

Studies representing RCTs or RCT pilot study and related to Iyengar yoga method exclusively

English language publications between 2000 and 2013.

Studies were excluded if the pain of spine (back or neck) was not the primary outcome, that is,[24] or the study was related to research of other health condition than back or neck pathology, that is,[25,26] if the study was not related to Iyengar yoga method that is,[27,28,29,30] or were not pertaining to the RCT study design that is,[31,32,33,34] Nevertheless, one study[37] with little sample size and pertaining to RCT pilot design was not excluded in the analyses since it was the first phase of the best presented RCT of the current review.[38]

Figure 1 presents the details of selection of studies. Consequently, only six studies were selected for review that presented results of well-designed, RCT and a pilot RCT. The six studies originated from US,[35,36] UK,[37,38] and Germany.[39,40] The rest 47 studies were excluded from the systematic review due to its nonrelationship to Iyengar method specifically or due to treating other medical health problems than spinal pain or not measuring pain outcome.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of inclusion and exclusion assessment

Study characteristics

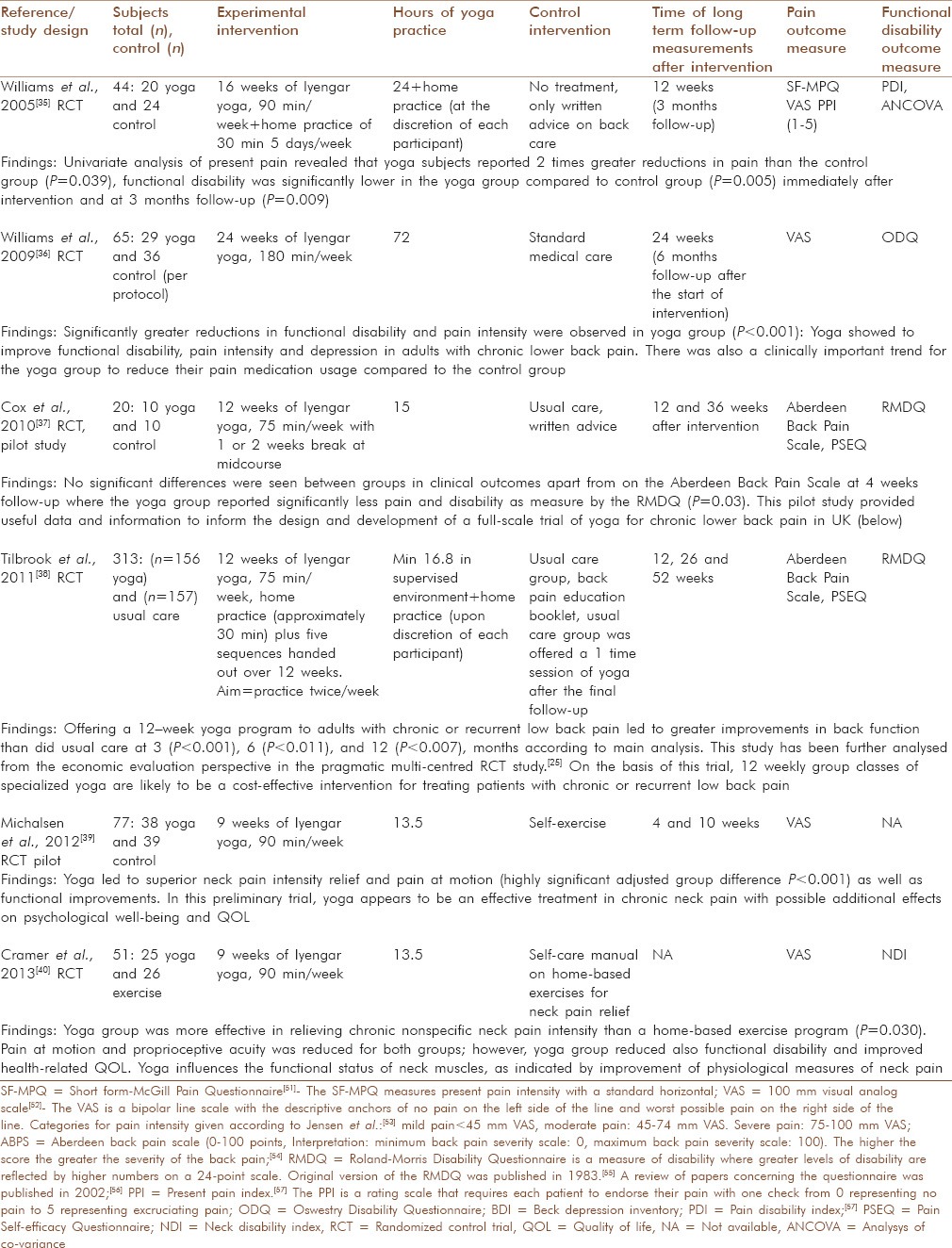

At this point, the above six RCTs were carefully reviewed in full text to be included in systematic literature review [Table 1]. Further on the quality appraisal, data analysis and results of the RCT studies have been undertaken.

Table 1.

Overview of identified studies

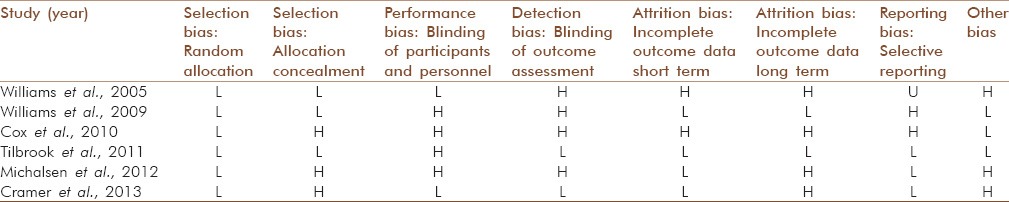

Quality appraisal – risk of bias within studies

The assessment of bias risks has been performed on the basis of the risk of bias summary template proposed by Cochrane Collaboration's reviews. The overview of the studies’ risk bias is presented in Table 2. Below focusing on selection, performance, detection, attrition, and reporting bias. The “L” symbol signifies the low-risk or meeting the criteria, the “H” symbolizes the high-risk of bias and “U” key refers to unclear risk of bias.

Table 2.

Risk of bias assessment for selected studies

In the study of Williams et al. 2005, the data collectors were blinded to the subjects’ treatment status and the subjects were randomly allocated to either yoga or control group using a random number generating program from JMP 4.0 statistical software (JMP is a registered trademark of the SAS Institute, Cary, NC). We have evaluated the selection and performance bias being at low-risk. Subjects in the yoga group were asked each week to report the frequency and duration of their yoga therapy practice at home. Upon completion of intervention, subjects were asked to complete and return social validation questionnaires and returned them in stamped, self-addressed envelopes. This procedure could have biased the blinding of outcome assessment; therefore, detection bias is at high-risk. The outcome measures were based on the functional disability as primary outcome, further on clinical pain, fear of movement, pain attitudes, coping strategies, self-efficacy, and range of motion, pain medication usage and adherence to yoga practice. To increase the power of the study authors recommend narrowing outcome variables to better inspect the studied question. “The attrition in this study was as high as 30% due to drop-outs; nevertheless, it reduced to 18.3% when subjects who discontinued in the study because they did not show up after the baseline assessment or turned out to be medically ineligible were eliminated”. Among other bias, we can classify the therapist bias since the principal investigator of the study (an Iyengar student for 14 years) who served as one of the yoga instructors, was not involved in data collection or data analysis of the results, which was conducted by other members of the research team, nevertheless was involved in the delivery of the yoga therapy intervention.

In the study of Williams et al. 2009 eligible participants were given randomly generated group assignments and enrolled in one of four cohorts. Participants were asked to complete consecutively numbered VAS and return through stamped, self-addressed envelopes at 12 (midway), 24 (immediately after) and 48 weeks (6 months follow-up) after the start of intervention. A research assistant was blinded to the participants’ group assignment; hence, the selection bias shows low-risk despite of single blinding. However, the yoga subjects reported clinically significant improvements in all outcomes (functional disability, pain intensity, depression, and use of pain medication) – most probably due to prompting of the monthly follow-up calls by research staff. The outcome assessors, thus, were not blinded at data collection. The authors provided detailed data on intervention effectiveness broken down into intention-to-treat and per-protocol. “The proportion of yoga subjects with clinically important improvements increased by 10-12% in the Oswestry Disability Index[57] (functional disability) and 8-14% in the VAS from the intention-to-treat to per-protocol at 12 and 24 weeks of follow-up, respectively.” Despite of strong evidence of positive changes in functional disability scale in comparison to intention-to-treat analyses, the strong reliance on self-report instrumentation has introduced reporting bias. The missing data in intention-to-treat and per-protocol analyses were replaced using the last observation carried forward and adjusted accordingly to eliminate attrition bias. The study suggests that a 24-week period of yoga practice and doing selective poses with range of props for lower back pain added to the success of the study.

In the study of Cox et al. 2010 the patients with preexisting lower back pain within the previous 18 months and were interested in participation in the study, underwent prerandomization screening for their eligibility. “The total percentage of randomized patients from originally identified list (7040) was 0.28%. Patients were randomized using computer generates random numbers by an independent data manager and allocated to either 12 weekly classes of yoga or usual care.” However, the prescreening and baseline questionnaires were timed separately, latter being introduced after randomization, which involved allocation bias. There is an evidence of imbalance between control (20% did not return follow-up data) and intervention groups (50% did not attend the classes), resulting in attrition bias. In view of the low attendance and differential response rate, it is difficult to interpret the clinical outcome date for a small sample, despite of the fact that yoga intervention group reported a greater decrease in pain (P = 0.003). This study is evaluated at high-risk based on bias assessment. Nevertheless, this pilot RCT study served a solid foundation for preparation of the much larger trial performed by the same team of authors.

In the study of Tilbrook et al. 2011, there have been two waves of recruitment during which the participants were mailed the invitation pack. Eligibility was determined during responses assessment by trial coordinators and confirmed through the participants’ general practitioner. “The randomization sequence was computer generated by an independent data manager.” A variable allocation ratio was used for each class and adjusted accordingly ensuring that there was equal number of participants in each group. Thus, the study shows low-risk in selection and allocation bias. Even though, yoga teachers performing intervention, were all trained the same treatment plan over 2 weekends, 50% of them were not coming from Iyengar yoga background that takes years of practice and guidance to tame. This has biased participants’ ultimate performance. “Analyses of the outcome data were conducted according to the original randomized treatment assignment regardless of adherence to protocol; the statistician was blinded to randomized group using SAS software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). The Fisher exact test was also used to explore the association between adherence and intervention preference.” There were missing data for the primary outcome and differential missing data (more in yoga group) for secondary outcomes that has biased the results. Overall, this is a high quality RCT that have showed low-risk of bias and delivered data consistent with findings.

In the study of Michalsen et al. 2012 the randomization process was well-designed: Patients were randomly allocated by a nonstratified block randomization offered by number generator of SAS software with varying block lengths and preparing sealed, sequentially numbered opaque envelopes containing treatment assignments by study biostatistician. The study information emphasized that both treatments (9 weeks Iyengar yoga group and self-care exercise program) might be useful for treatment of chronic neck pain. Since control group had self-applied physical intervention, the study participants were not blinded to treatment group. “Data collection was performed by nonblinded research assistants that might have influenced the overestimation of effects.” Thus, performance and detection bias is of high risk in this study. The design of study was following intention-to-treat analysis, the drop-out rate was higher than anticipated (24 subjects withdrew and were lost to follow-up). However, the researchers used the sensitivity analysis to investigate the influence of participants’ drop-out in the result which was comparable to intention-to-treat analysis on short-term outcome, thus eliminating attrition bias. Nevertheless, there is no information on the long-term follow-up beyond 10 weeks. Other bias of the study was formal difference between the two treatment types (time, attention, social interaction) favoring yoga intervention.

Finally, in the study of Cramer et al. 2013 patients were randomly allocated to the treatments by a nonstratified block randomization with randomly varying block lengths with the help of SAS software. On this basis, the biostatistician has prepared sealed, sequentially numbered envelopes containing the treatment assignments. Upon baseline assessment, the study physician revealed the patient's assignment. The outcome assessor was kept blind to allocated treatment throughout the study. “All analyses were performed on intention-to-treat basis including all patients being randomized, regardless of whether or not they gave a full set of data or adhered to the study protocol and missing data adjusted.” Thus, from perspective of selection, performance and detection bias the study presents low risk. The study is lacking a long-term follow-up and impossibility of blinding patients to treatment allocation due to self-care control group's designation. We have evaluated allocation concealment and long-term attrition bias being at high risk. Other bias that study represents is the effectiveness of intervention due to the fact the yoga instructor was also a physiotherapist.

Results of individual studies

The above six articles were included in the systematic literature review to observe the effectiveness of the Iyengar yoga therapy on spinal pain conditions. The articles were published in peer-reviewed specialized journals and were based on RCT study design. Spinal pain reviewed in this article comprises chronic cervical (neck) and lumbar (lower back) pain. Patients who experience back and neck pain are limited in their daily activities and may experience inappropriate neuromuscular adaptations to maintain and/or preserve primary functions such as walking, running, sitting, etc.[18] The intervention groups were undergoing yoga practice assisted and supervised by the certified and experienced Iyengar yoga teachers. Teachers used necessary props to specifically target a group of muscles with variations of postures that gradually released muscle tension, opened up joint spaces designed to increase circulation and decrease inflammation.[35] The control groups were given either written advice (two studies), underwent self-exercise (two studies), or standard medical care (nonspecified, two studies). Four studies have used VAS and two have used the Aberdeen Back Pain Scale (ABPS) to report the pain outcome measure to compare the results of pre- and post-intervention, and only four studies have used the functional disability outcome measure as primary and secondary outcome measures. The measures were reported at the baseline, immediately postintervention treatment and at the follow-up after intervention (4, 10, 12, 24, 36, and 48 weeks).

Altogether 570 subjects were taken into the studies with mean age between 18 and 67. Population was relatively homogenous in terms of clinical conditions for back pain or neck pain. The duration of intervention varied among the studies, from 9 to 24 weeks. The mean duration of intervention (yoga practice) was 90 min/week except the study of Williams et al. 2009,[36] which was based on 180 min/week (twice 90 min class/week). The total yoga hours (hours per week multiplied by number of weeks of intervention) ranged from 13.5 and 72, with mean 25 h.

In the Tilbrook et al.[38] trial, multiple experienced yoga teachers (n = 12) taught the “Yoga for Healthy Lower Backs” program to the 156 yoga group participants. Half (n = 6) of these teachers were initially non-Iyengar trained. The lead yoga consultant (Alison Trewhela), who designed the program and trained the 12 yoga teachers (50% Iyengar yoga teachers; 50% teachers from various schools and methods under the British Wheel of Yoga umbrella) for the original RCT, is an Iyengar yoga teacher. This multi-centered trial thereby proffers generalizability.

According to the pain outcome measures relevant to each study, the six studies have showed the considerable decrease in the pain for the yoga intervention groups, including the study,[39] where the pain outcome was measured at motion and at rest (static state). For the four studies, the VAS pain outcome measure was taken as a base of analyses, except the[37] and Tilbrook et al.[38] where the RMDQ scores were resulted to be more accurate measurements versus ABPS. More data were collated for the RMDQ as it was the primary outcome measure with less loss to follow-up; plus it is worth noting that these two trials excluded those with sciatic pain below the knee, according to Alison Trewhela, one of the contributors to the study. For unification purposes of consistent measurement comparison, the preintervention stage is corresponding to the baseline, the postintervention - to the immediate results after intervention and follow-up - to the last measured follow-up. Two studies[39,40] do not represent longer-term follow-up, only the postintervention follow-up.

Synthesis of results

In the study of Williams et al. 2005[35] after the 16-week intervention, the mean VAS score fell to 1.0 for the yoga group (56.5%) and to 2.1 for the control group (31%) as compared with the baseline (P = 0.146). At the 3-month follow-up, the mean VAS score was 0.6 for the yoga group (69.6% of decrease in present pain) compared to 2.0 for the control group (37.5% reduction of present pain); the difference between the two groups thus became statistically significant (P = 0.039).

In the study of Williams et al. 2009[36] statistically significant treatment group × time interactions were observed for VAS (P = 0.001). At postintervention, at 24 weeks, the yoga group allowed a 56.0% reduction in VAS in per protocol group (P = 0.001); the proportion of yoga subjects with clinically important improvements increased by 8-14% for VAS; at 6 months follow-up linear contrasts indicated that the yoga group had significantly greater (58%) reductions in VAS (P = 0.002).

In the pilot RCT study of Cox et al.[37] change as measured by the RMDQ was the primary clinical outcome (changes in the ABPS, short-form-12 [SF-12], EQ-5D and pain self-efficacy were secondary clinical outcomes). The United Kingdom back pain exercise and manipulation trial found that a change in the RMDQ score of 1.57 points was a cost-effective difference. Although there is no consensus, a change of 1.1-2.5 on the RMDQ has been recommended as clinically important.[45,46] This scale has been found to be sensitive to change, reliable, and valid. At 4 weeks follow-up 80% of the yoga group had improved by at least two points compared to 37.5% of the control group, mean difference 1.88 (95% CI = -3.18 to 6.94), P = 0.43 for RMDQ and mean difference 8.39 (95%CI=1.18-15.6), P = 0.03 for VAS. At 12 weeks follow-up 66.6% of the yoga group had improved by at least two points on the RMDQ compared to 55.6% of the usual care group, P = 0.72).[37]

In the study of Tilbrook et al.[38] The yoga group had better back function at 3 (primary outcome),,6 and 12 (secondary outcome) months than the usual care group. The adjusted mean RMDQ score was 2.17 points (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.03-3.31 points), P < 0.001, lower in the yoga group at 3 months (postintervention), -1.48 points (CI: 0.33-2.62 points), P < 0.011, lower at 6 months, and -1.57 points (CI:-2.71 to -0.42 points), P < 0.007 lower at 12 months (follow-up). In the trial it was found out, that individuals offered yoga benefited, on an average, 2.17 fewer limited activities at 3 months and by 1.57 fewer limited activities at 12 months. The activities measured by RMDQ include, for example, walking more slowly than usual, standing for only short periods and not doing any of the usual jobs around the house. Additional postintervention follow-up yoga classes might have shown even greater improvements at the long-term follow-up points (6 and 12 months). The yoga and usual care groups had similar back pain and general health scores at 3,6 and 12 months, and the yoga group had higher pain self-efficacy scores at 3 (P = 0.062) and 6 months (P = 0.186), but not at 12 months (P = 0.58).

In the study of Michalsen et al.,[39] as a primary outcome, mean neck pain score at week 10 (postintervention) was reduced from 44.3 to 13.0 in the yoga group and from 41.9 to 34.4 in the exercise group. This resulted in a highly significant adjusted group difference (-20.1, 95% CI: -30.0, -10.1; P < 0.001). Pain at motion was reduced from 53.4 ± 18.5 to 22.4 ± 18.7 at week 10 by yoga and from 49.4 ± 22.8 to 39.9 ± 21.5 by self-care/exercise (group difference: −18.7, 95% confidence interval: -29.3, -8.1; P < 0.001). Significant treatment effects of yoga were also found for pain-related apprehension, disability, QOL, and psychological outcomes or the yoga group compared with the control group, there was a significant and clinically important adjusted reduction of pain intensity of $20-mm VAS. Within the yoga group, the pre- to post-treatment reduction of 30-mm VAS also represent a significant and clinically important pain reduction, which corresponds to a mild-to-moderate effect size. The beneficial outcomes of the yoga intervention are particularly of interest given participants’ long history of neck pain.

Study of Cramer et al.,[40] at week 9 (postintervention) the yoga group experienced a significantly greater reduction in pain intensity compared with the exercise group (between group difference - 13.9 mm according to VAS; 95% CI:-26.4 to -1.4; P = 0.030). Pain at motion was reduced for both groups. The yoga group reported less disability and better mental QOL. Range of motion and proprioceptive acuity were improved and the pressure pain threshold was elevated in the yoga group.

The follow-up measure data included in three studies[35,36,38] have shown that this treatment carries long-term effect due to further decrease in pain measure outcomes. This systematic review found strong evidence for short-term effectiveness and moderate evidence for long-term effectiveness of yoga for chronic spine pain in the most important patient-centered outcomes.[51]

DISCUSSION

Summary of evidence

One of the primary causes of back pain is muscle tension.[42] Many people are tight in places that affect the spine, such as the hips and shoulders. As you work through yoga poses, your muscles will stretch and loosen up in areas where they were previously tense.[27] These are muscles you may not often stretch, and yoga provides an atmosphere to do so. Yoga stretches may be enough for people whose back pain is directly related to stress or poor posture.[21] The findings showed there was a significant and clinically important reduction in pain intensity in the yoga group. The authors reasoned that yoga might enhance both the toning of muscles and releasing of muscle tension. Relaxation responses, therefore, could reduce stress related muscle tension and modify neurobiological pain perception. They concluded, based on the study data, that Iyengar yoga can be a safe and effective treatment option for chronic spinal pain. The study results are consistent with the demonstrated benefits of yoga for treating spinal pain.[26] The authors also suggested that as yoga practitioners develop increasing awareness of muscle use and joint position, they could better change habitual posture patterns in daily life.[43]

Yoga is often recommended as an evidence-based additional therapy intervention for back and neck pain. Being more than exercise, yoga seems to be able to improve body awareness, pain acceptance, and coping.[44]

Limitations of studies

There is limited number of well-designed evidence-based studies exploring beneficial effects of Iyengar yoga on various health conditions including acute and chronic spinal pain and its impact on behavioral change with the purpose of improvement of QOL. The studies included in this systematic review showed to have varied methodological quality: Three RCTs[35,36,38](50%) were of high quality (showing up to maximum three bias out of eight), two RCTs[39,40] have showed above three bias, hence considered to be of high-risk. One study[37] being a small sample sized pilot RCT in view of preparation for the larger trial[38] is considered of high-risk and low quality, but has been used as a preparatory stage for the well-designed RCT of Tilbrook et al. 2011. Among other sources of bias, we have seen therapist bias of the research instructors directly involved in conducting of the trial[35,40] and formal differences between two treatment groups.[39] Overall, except for one study (Tilbrook et al. 2011) the trials related to the small sample size; therefore, the effect size might have been overestimated. Further limitations include bias in analyzing multivariate pain outcome measures, in selecting criteria for measuring primary and secondary outcome, in pain medication analyses (where applicable), intervention and control groups might not be fully comparable given that they not always started with the same number of pain outcome measure, lack of long-term follow-up (<3 months postintervention) in two studies studies.[39,40] Further studies should focus on the long-term effectiveness of Iyengar yoga for spine (back and neck) pain and further exploration of physiological and psychological mechanisms of yoga.

Safety of yoga

The safety of yoga is being widely discussed with its increasing popularity. Can yoga be also harmful for patients with spinal pain? Like other exercise activity, the risks of injury from improperly performing yoga postures vary depending on where and with whom the yoga is being practiced.[42] Iyengar teachers are trained to work even with students with serious limitations and injuries, to recognize when students are ready for certain asanas, and not to ask them to go beyond their readiness. Alison Trewhela underlines that teachers should help students understand that they should go to the “optimum” position in a yoga pose, which is very often not the same as the “maximum” position.

Data from research studies with experienced yoga instructors have shown occasional adverse events. Data from Williams et al. study in 2005[35] show one serious adverse event among 20 patients randomized to yoga. This patient had symptomatic osteoarthritis and herniated a disc during the study. However, the event was reviewed by a medical panel and it was determined that the event was not caused by practicing yoga in this study. In the study with the largest number of participants,[38] one adverse event was classified as serious possibly related to yoga, but this person had a history of severe pain after any physical activity. In accordance with rigorous trial protocol, adverse events were reported to nonyoga teaching administrative staff. The remaining 11 were classified as nonserious and mostly related to increased pain. In the usual care group, two serious adverse events occurred. More general review of nonpharmacological treatments for chronic back pain concluded that these interventions seldom cause harm, but better studies and better reporting is needed.[41] The study of Cramer et al. showed no serious adverse events. Nine patients in the yoga group and eight patients in the exercise group reported a transient worsening of neck pain or muscle soreness after practice. Other minor adverse events were reported by three patients in the yoga and two patients in the exercise group and included transient limb pain, migraine, and vertigo after practice.[40]

Specific asanas for spine pain

Even exercise-based yoga interventions differ from purely gymnastic exercises in that yoga practitioner focuses his/her's mind on the postures with inner awareness.[29] All postures must be performed in a consciously aware manner that is fully appreciative of the intricacy of each movement. These movements are “intricate” and highlight the body - mind nature of yoga that emphasizes awareness, concentration, and bidirectional communication between the mental, nervous, skeletal, and muscular systems.[45] Yoga is regarded as a safe method and a therapy that provides a wide range of benefits. Among the innumerable yoga asanas, there are some, which work specially on spine. These asanas help in relaxing the tight muscles, reducing the tension and strengthening them.[46] Yoga practices these asanas along with pranayama, correcting the vertebral curvatures, with respective angles, strengthening thoracic and abdominal cavities along with respiratory muscles supporting the maintenance of proper posture.[47]

Analyzing papers reviewed in this article, the below listed yoga postures have been identified as common specific asanas designated to reduce spinal pain (back and neck) consistently mentioned in the studies which revealed the details of intervention program:

Tadasana – Mountain pose and various arm/shoulder positions

Ardha Uttanasana – Half forward bend to wall or ledge

Chair Bharadvajasana – Seated chair twist

Adho Mukho Virasana – Downward-facing hero pose

Adho Mukha Svanasana – Downward-facing dog pose

Utthita Trikonasana – Extended triangle pose

Virabhadasana II – Warrior pose II

Utthita Parsvakonasana – Extended side angle pose

Prasarita Padottanasana – Intense leg stretch

Supta Padangustasana – Reclining big toe (and variations)

Prone Savasana – Lying prone corpse pose (with weights)

Supta Pavanamuktasana – Lying both knees to chest pose

Supta Savasana – Lying supine corpse pose.

All the trials had somewhat different sequences, postures, variations of certain postures and the corresponding props. The postures as such are not the most important aspect of a good yoga program; more important is the way in which they are to be performed according to individualized modifications and using appropriate props. An experienced yoga teacher can instruct how beginners should perform this specialized yoga for safety and efficacy. The yoga practice usually progresses over time, rather than solely through repetition. The order of sequencing is adjusted due to the full program/intervention.

Other impacts of Iyengar yoga

It is important to mention, that there exist a number of randomized control studies of Iyengar yoga's healing effects for the cases of mobility in older community, postural stability and gait in elderly women, Parkinson's disease, multiple sclerosis, breast cancer survivors’ cases, blood pressure in prehypertension and hypertension stages, bronchial asthma, osteoarthritis of the knee, rheumatoid arthritis, carpal tunnel syndrome, distress in women, positive affects on brain wave vibration and mindfulness, decreasing depression and stress.[33] People who practice yoga regularly do so to maintain their health and well-being, improve physical fitness, relieve stress, and enhance QOL.[47]

Besides pain and functional disability assessment, selective studies in this systematic review have explored other impacts of yoga intervention linked to change in QOL. Williams et al., 2009[36] have reported on the impact of Iyengar yoga on the psychological well-being, specifically in reducing depression among individuals with chronic low back pain. Using the beck depression inventory, individuals randomized to the yoga group showed greater improvements in depression than those randomized to the control group. Similar conclusions reached the RCT study of Cramer et al. 2013[40] with the help of SF-36 survey tool showing significant improvement for yoga group for mental QOL, social functioning, emotional role functioning, mental health, and bodily pain improvement.

CONCLUSION

The main finding of this review suggests that the practice of yoga can decrease pain and increase functional ability in patients with spinal pain. This review, however, has several limitations: The total number of trials existing up to date on Iyengar yoga method treating spine pain is rather limited, as well as the overall sample sizes are relatively small; the trials used various reporting data which makes it more difficult to compare results homogeneously; lack of long-term follow-up assessment in some studies; finally the presented bias of each study may influenced the validity of results to be able to draw rigorous conclusions. Despite these limitations, this systematic review has found evidence of Iyengar yoga interventions being useful in treating spinal pain and having other therapeutic effects. Chronic spinal pain can have a significant impact on an individual's ability to remain an active and productive member of the work force due to increased absenteeism, duty restrictions, or physical limitations from pain.[48] An alternative treatment that could reduce nonspecific chronic spinal pain[49] would benefit both employees and employers, and society in general. Exercising and remaining active are part of most guidelines and routine care recommendations but are not well-defined or systematically applied.[50] Yoga shows promise as a therapeutic intervention, but relationships between yoga practice and health are yet underexplored. Future studies exploring therapeutic effects of Iyengar yoga and its effectiveness in treating chronic conditions (especially musculoskeletal disorders and pain) have to be performed within the accepted standards of trial design and reporting.

In conclusion, more evidence-based larger scale researches with longer-term follow-up need to be done to increase the therapeutic weight and value of Iyengar yoga as a part of complementary alternative medicine being preventive and rehabilitation method among general population. This might also encourage the population to practice; thus, subsequently leading to lifestyle modifications.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This systematic review was performed as a part of curriculum of Master of Advanced Studies in Public Health under the umbrella of Institute of Global Health, Faculty of Medicine, University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland. The author thanks Alison Trewhela, a mentor and senior Iyengar yoga teacher and practitioner since 1979, for her support and sharing of her expertise and insight knowledge for this systematic review. Alison was the lead yoga consultant for The University of York and Yoga for low back pain research team (funded by the Charity Arthritis Research UK). She designed, trained teachers for, and compiled educational resources for the trial's “Yoga for Healthy Lower Backs” intervention and is a co-author of five associated published research papers, two of which (a pilot study and a RCT) are included in this review. Since 2004, as a visiting specialist and tutor for Exeter University, Alison has taught groups of UK medical students about the benefits of yoga. Among her many achievements, she won ICNM's 2013 “Most Outstanding Contribution to Complementary Medicine” award, which defines well her immense participation in the process of integrating therapeutic and specialized yoga within complementary and mainstream medicine.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wu SJ, Green A. A Projection of Chronic Illness Prevalence and Cost Inflation, 2000. Santa Monica, California, USA: RAND Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davey Smith G, Shipley MJ, Batty GD, Morris JN, Marmot M. Physical activity and cause-specific mortality in the Whitehall study. Public Health. 2000;114:308–15. doi: 10.1038/sj.ph.1900675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teixeira-Lemos E, Nunes S, Teixeira F, Reis F. Regular physical exercise training assists in preventing type 2 diabetes development: Focus on its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2011;10:12. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-10-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedenreich CM. Physical activity and breast cancer: Review of the epidemiologic evidence and biologic mechanisms. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2011;188:125–39. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-10858-7_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cox BD, Whichelow MJ, Prevost AT. Seasonal consumption of salad vegetables and fresh fruit in relation to the development of cardiovascular disease and cancer. Public Health Nutr. 2000;3:19–29. doi: 10.1017/s1368980000000045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heidemann C, Schulze MB, Franco OH, van Dam RM, Mantzoros CS, Hu FB. Dietary patterns and risk of mortality from cardiovascular disease, cancer, and all causes in a prospective cohort of women. Circulation. 2008;118:230–7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.771881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Batty GD, Kivimaki M, Gray L, Smith GD, Marmot MG, Shipley MJ. Cigarette smoking and site-specific cancer mortality: Testing uncertain associations using extended follow-up of the original Whitehall study. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:996–1002. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teo KK, Ounpuu S, Hawken S, Pandey MR, Valentin V, Hunt D, et al. Tobacco use and risk of myocardial infarction in 52 countries in the INTERHEART study: A case-control study. Lancet. 2006;368:647–58. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69249-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laatikainen T, Manninen L, Poikolainen K, Vartiainen E. Increased mortality related to heavy alcohol intake pattern. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57:379–84. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.5.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mukamal KJ, Chen CM, Rao SR, Breslow RA. Alcohol consumption and cardiovascular mortality among U.S. adults, 1987 to 2002. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:1328–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.10.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barth J, Schumacher M, Herrmann-Lingen C. Depression as a risk factor for mortality in patients with coronary heart disease: A meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:802–13. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000146332.53619.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mookadam F, Arthur HM. Social support and its relationship to morbidity and mortality after acute myocardial infarction: Systematic overview. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1514–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.14.1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seeman TE. Health promoting effects of friends and family on health outcomes in older adults. Am J Health Promot. 2000;14:362–70. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-14.6.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wallander MA, Johansson S, Ruigómez A, García Rodríguez LA, Jones R. Morbidity associated with sleep disorders in primary care: A longitudinal cohort study. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;9:338–45. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v09n0502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andersson GB. Epidemiological features of chronic low back pain. Lancet. 1999;354:581–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01312-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haslett C, Chilvers ER, Hunter JA, Boon NA. Davidson's Principles and Practice of Medicine. 18th ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1999. p. 815. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iyengar PS. Yoga and the new millennium. Yoga Rahasya. 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carter C, Stratton C, Mallory D. Yoga to treat nonspecific low back pain. AAOHN J. 2011;59:355–61. doi: 10.3928/08910162-20110718-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Posadzki P, Ernst E. Yoga for low back pain: A systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30:1257–62. doi: 10.1007/s10067-011-1764-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, Appel S, Wilkey S, Van Rompay M, et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990-1997: Results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA. 1998;280:1569–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.18.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. [Last accessed on 2014 May 20]. Available from: http://www.life.gaiam.com/article/how-does-yoga-relieveback-pain .

- 22. [Last accessed on 2014 May 20]. Available from: http://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/prisma/

- 23.Green S, Higgins JP, Alderson P, Clarke M, Mulrow CD, Oxman AD. Introduction. In: Higgins JP, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Ch. 1. Chichester, UK: John Wiley and Sons; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Torgerson C. Systematic Reviews. London: Continuum; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chuang LH, Soares MO, Tilbrook H, Cox H, Hewitt CE, Aplin J, et al. A pragmatic multicentered randomized controlled trial of yoga for chronic low back pain: Economic evaluation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2012;37:1593–01. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182545937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tekur P, Chametcha S, Hongasandra RN, Raghuram N. Effect of yoga on quality of life of CLBP patients: A randomized control study. Int J Yoga. 2010;3:10–7. doi: 10.4103/0973-6131.66773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tekur P, Nagarathna R, Chametcha S, Hankey A, Nagendra HR. A comprehensive yoga programs improves pain, anxiety and depression in chronic low back pain patients more than exercise: An RCT. Complement Ther Med. 2012;20:107–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Galantino ML, Bzdewka TM, Eissler-Russo JL, Holbrook ML, Mogck EP, Geigle P, et al. The impact of modified Hatha yoga on chronic low back pain: A pilot study. Altern Ther Health Med. 2004;10:56–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Little P, Lewith G, Webley F, Evans M, Beattie A, Middleton K, et al. Randomised controlled trial of Alexander technique lessons, exercise, and massage (ATEAM) for chronic and recurrent back pain. BMJ. 2008;337:a884. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lamb SE, Hansen Z, Lall R, Castelnuovo E, Withers EJ, Nichols V, et al. Group cognitive behavioural treatment for low-back pain in primary care: A randomised controlled trial and cost-effectiveness analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:916–23. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62164-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams K, Steinberg L, Petris J. Therapeutic application of Iyengar yoga for healing chronic low back pain. Int J Yoga Ther. 2003;13:55–67. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sawyer AM, Sarah KM, Warren GL. Impact of yoga on low back pain and function: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Yoga Phys Ther. 2012;2:4. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iyengar Yoga, Research 1996-2012, Compiled by Ross A. 2012. [Last accessed on 2014 Jun 2]. Available on: http://www.iyengaryoganorthcounty.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/Iyengar-Yoga-Research.pdf .

- 34.Cramer H, Lauche R, Haller H, Langhorst J, Dobos G, Berger B. “I’m more in balance”: A qualitative study of yoga for patients with chronic neck pain. J Altern Complement Med. 2013;19:536–42. doi: 10.1089/acm.2011.0885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williams KA, Petronis J, Smith D, Goodrich D, Wu J, Ravi N, et al. Effect of Iyengar yoga therapy for chronic low back pain. Pain. 2005;115:107–17. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williams K, Abildso C, Steinberg L, Doyle E, Epstein B, Smith D, et al. Evaluation of the effectiveness and efficacy of Iyengar yoga therapy on chronic low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;34:2066–76. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b315cc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cox H, Tilbrook H, Aplin J, Semlyen A, Torgerson D, Trewhela A, et al. A randomised controlled trial of yoga for the treatment of chronic low back pain: Results of a pilot study. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2010;16:187–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tilbrook HE, Cox H, Hewitt CE, Kang’ombe AR, Chuang LH, Jayakody S, et al. Yoga for chronic low back pain: A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:569–78. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-9-201111010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Michalsen A, Traitteur H, Lüdtke R, Brunnhuber S, Meier L, Jeitler M, et al. Yoga for chronic neck pain: A pilot randomized controlled clinical trial. J Pain. 2012;13:1122–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cramer H, Lauche R, Hohmann C, Lüdtke R, Haller H, Michalsen A, et al. Randomized-controlled trial comparing yoga and home-based exercise for chronic neck pain. Clin J Pain. 2013;29:216–23. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e318251026c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cramer H. Yoga for chronic low back and neck pain. Gen Med. 2013;1:107. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chou R, Huffman LH. American Pain Society, American College of Physicians. Nonpharmacologic therapies for acute and chronic low back pain: A review of the evidence for an American Pain Society/American College of Physicians clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:492–504. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-7-200710020-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. [Last accessed on 2014 May 20]. Available from: http://www.health.india.com/news/iyengar-yoga-effectivein-treating-chronic-neck-pain .

- 44. [Last accessed on 2014 May 20]. Available from: http://www.yogauonline.com/yogatherapy/yoga-for-backpain/yoga-for-shoulder-and-neck-pain/1191051013-study-iyengar-yogapractic .

- 45.Erik JG, Marisa S, Douglas C. VA San Diego Healthcare System. USA: University of California San Diego, SDSU/UCSD Joint Doctoral Program in Clinical Psychology; 2013. Yoga as a treatment for low back pain: A review of the literature; pp. 332–52. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wolsko PM, Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Kessler R, Phillips RS. Patterns and perceptions of care for treatment of back and neck pain: Results of a national survey. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2003;28:292–7. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000042225.88095.7C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ross A, Friedmann E, Bevans M, Thomas S. Frequency of yoga practice predicts health: Results of a national survey of yoga practitioners. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:9832. doi: 10.1155/2012/983258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shelerud R. Epidemiology of occupational low back pain. Occup Med. 1998;13:1–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Selfridge N. Yay yoga! More evidence for helping low back pain. Altern Med Alert. 2012;15:33–4. [Google Scholar]

- 50. [Last accessed on 2014 May 20]. Available from: http://www.edition.cnn.com/2011/10/24/health/yoga-easesback-pain .

- 51.Melzack R. The short-form McGill pain questionnaire. Pain. 1987;30:191–7. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(87)91074-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huskisson EC, Sturrock RD, Tugwell P. Measurement of patient outcome. Br J Rheumatol. 1983;22:86–9. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/xxii.suppl_1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jensen MP, Chen C, Brugger AM. Interpretation of visual analog scale ratings and change scores: A reanalysis of two clinical trials of postoperative pain. J Pain. 2003;4:407–14. doi: 10.1016/s1526-5900(03)00716-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ruta DA, Garratt AM, Wardlaw D, Russell IT. Developing a valid and reliable measure of health outcome for patients with low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1994;19:1887–96. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199409000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roland M, Morris R. A study of the natural history of back pain. Part I: Development of a reliable and sensitive measure of disability in low-back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1983;8:141–4. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198303000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Roland M, Fairbank J. The Roland-Morris disability questionnaire and the oswestry disability questionnaire. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:3115–24. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tait RC, Chibnall JT, Krause S. The Pain Disability Index: Psychometric properties. Pain. 1990;40:171–82. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(90)90068-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]