Abstract

Background:

Exercise can be beneficial for cardiopulmonary, musculoskeletal or neurological systems, and other factors including mood, and may be beneficial in reducing fall risks, dementia and variables associated with quality of life (QOL). Parkinson's disease (PD) produces progressive motor and cognitive deterioration that may leave those inflicted unable to participate in standard exercise programs. Alternative forms of exercise such as yoga may be successful in improving physical function, QOL and physiological variables for overall well-being.

Aim:

This randomized controlled pilot study investigated the effectiveness of yoga intervention on physiological and health-related QOL measures in people with PD.

Methods and Materials:

Thirteen people with stage 1-2 PD were randomized to either a yoga (n = 8) or a control group (n = 5). The yoga group participated in twice-weekly yoga sessions for 12 weeks. Participants were tested at baseline, and at 6 and 12 weeks using the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS), clinical measures of health-related QOL and physiological measures.

Results:

Significant improvement in UPDRS scores (P = .006), diastolic blood pressure (P = 0.036) and average forced vital capacity (P = 0.03) was noted in the yoga group over time. Changes between groups were also noted in two SF-36 subscales. Positive trends of improvement were noted in depression scores (P = 0.056), body weight (P = 0.056) and forced expiratory volume (P = 0.059). Yoga participants reported more positive symptom changes including immediate tremor reduction.

Conclusions:

The results suggest that yoga may improve aspects of QOL and physiological functions in stages 1-2 PD. Future larger studies are needed to confirm and extend our findings of the effects of yoga in PD.

Keywords: Blood pressure, depression, Parkinson's disease, pulmonary function, quality of life, yoga

INTRODUCTION

Parkinson's disease (PD) affects neurological, physiological and psychological functions and quality of life (QOL). Physical contributors such as dyskinesias, decreased mobility, fatigue and motor complications worsen QOL.[1,2] Psychological variables like depression[3] correlate with reduced QOL. QOL remains important as PD symptoms, secondary complications and declining functional independence mount. Although treatments target motor symptoms, proper identification and subsequent treatment for psychological measures may be overlooked.[3] Compromised pulmonary function may also lead to impairment in activities of daily living (ADLs) and physical function[4] and affect exercise tolerance,[5] causing fatigue and thereby reducing QOL.

Exercise intervention has well-documented beneficial effects on PD symptoms and QOL. Several forms of exercise show improvement in ADLs, perceived health status, fall risk, QOL and motor performance.[6,7] Yoga improves depression, fatigue, wellbeing and QOL for people with chronic conditions.[8] Yoga also improves respiratory pressure,[9] while yogic breathing techniques have an immediate effect on lowering blood pressure in healthy people.[10] We reported the positive impact of yoga on motor function in people with PD.[11] The purpose of this study was to discern if physiological and QOL-related benefits of yoga exist in individuals with PD. Because overall function measured by the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) was investigated, we wanted to discern whether yoga affects the non-motor aspects of PD.

METHODS

The participants and procedures have been described previously.[11] This pilot study presents additional findings. Medical information and self-reported symptoms included time of PD diagnosis, current medications, PD-related symptoms, physical and social activity levels, and fall incidents. If there was a major medication change, participants were allowed to complete yoga training but data were not used after the medication change.

The UPDRS was the primary clinical measure of function. Health-related QOL measures included the modified falls efficacy scale (FES), the geriatric depression scale (GDS) and the SF-36. Physiological measures included weight, resting heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure and standard pulmonary function tests calculated by a Puritan - Bennett Renaissance II spirometer (Covidien - Puritan Bennett™, Boulder, CO, USA). All measures were gathered at baseline, 6 weeks and 12 weeks.

Data were analyzed using the Sigma Plot 11.0 (SyStat Software, San Jose, CA, USA). Frequencies of self-reported questionnaire items were analyzed. The primary analysis used independent t-tests to assess the baseline group differences and one-way repeated measures ANOVA to measure change over time, with P = 0.05 considered statistically significant. Non-parametric tests were used if assumptions were not met.

RESULTS

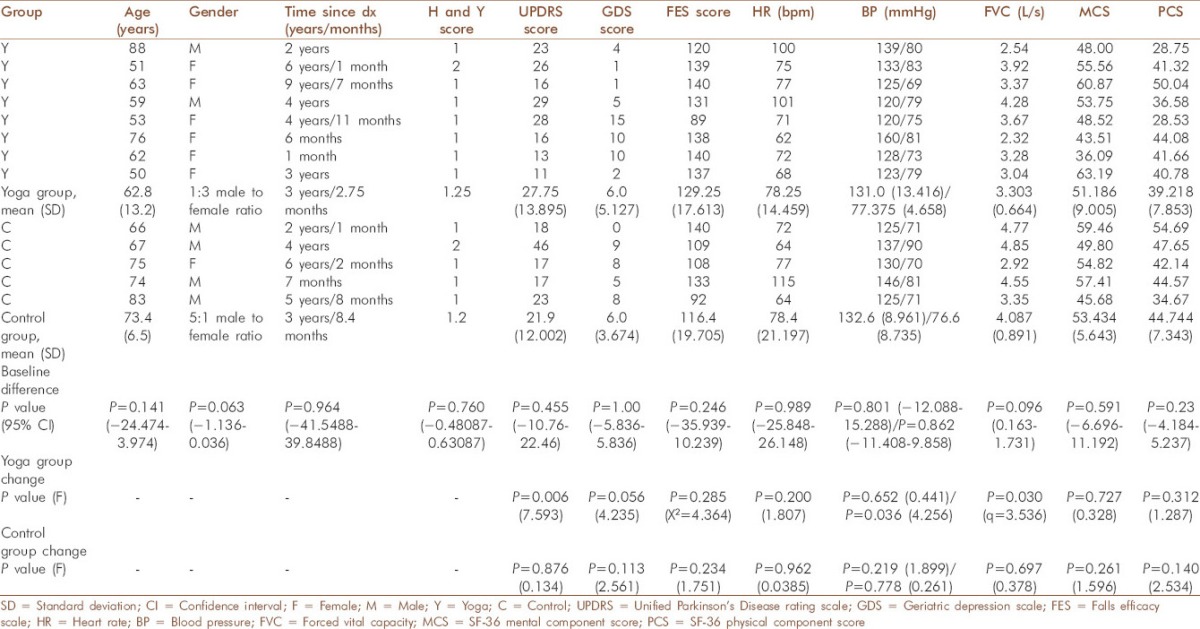

Table 1 reflects the participant characteristics at baseline and changes over time. The control group's mean age was older than that of the yoga group. Gender recruitment was fairly even, but random allocation into groups divided males predominantly into the control group and more females into the yoga group. The only baseline group differences existed in bodily pain (P = 0.006) and role limitations due to emotional problems (P = 0.038) sub-scales of the SF-36.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

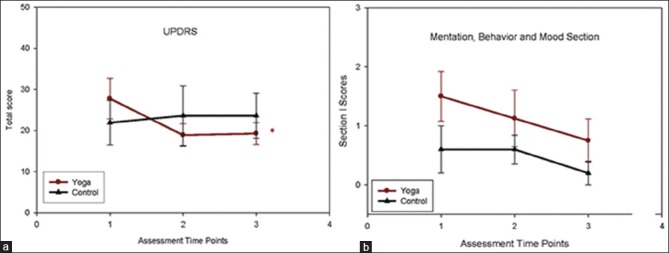

The UPDRS showed a significant improvement in the yoga group over time, with the largest gain in the first 6 weeks of intervention [Figure 1a]. Although UPDRS mentation, behavior and mood subsection scores improved with yoga, they were not significantly different in either group [Figure 1b].

Figure 1.

Primary outcome measure: Unified Parkinson's disease rating scale (UPDRS). (a) UPDRS score improved significantly with the yoga group (*) over time (P = 0.006, F = 7.593, df = 2) but not the control group (P = 0.876). (b) Mentation, behavior and mood subsection of the UPDRS. Both groups showed minimal symptoms in this subsection, with 0 being no symptoms and 12 being severe symptoms

At baseline, one control and two yoga participants had reached the ceiling on the modified FES. At the final assessment, one control and five yoga participants reached complete confidence in performing activities. At baseline, no control participants displayed depression measured by the GDS. Only three yoga participants displayed mild depression. At the final evaluation, only one yoga participant remained mildly depressed (P = 0.056). The baseline group differences in the two domains of the SF-36 were no longer significant at the final assessment (P = 0.435 and P = 0.724). There was a significant reduction in diastolic blood pressure in the yoga group only (P = 0.036). All participants had mild pulmonary obstruction as interpreted from flow volume graphs and volume time graphs. The only pulmonary function test, average forced vital capacity (FVC), showed significant improvement in the yoga group (P = 0.03). There was also a trend of improved forced expiratory volume in 1 s over time in the yoga group (P = 0.059) but not in the control group (P = 0.962).

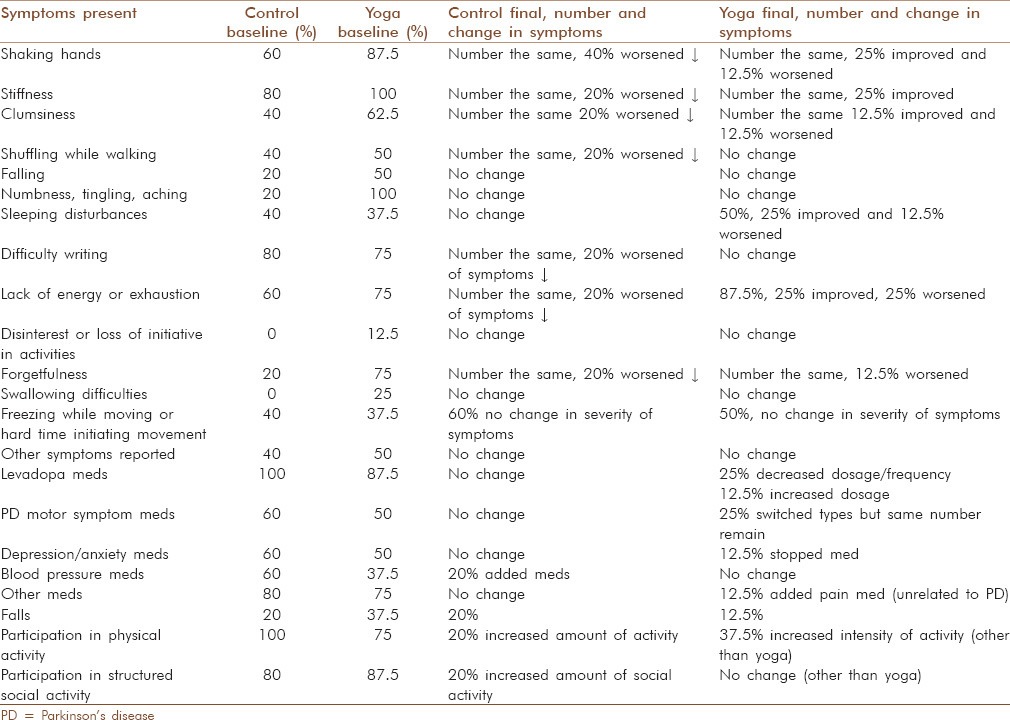

Medical information and self-reported symptoms are summarized in Table 2. At baseline, the yoga group reported swallowing difficulties and disinterest or loss of initiative in activities, while the control group reported none. The yoga group more commonly reported hand shaking, stiffness, clumsiness, falling, sensory disturbances or pain, lack of energy or exhaustion and forgetfulness than the control group. Between 20 and 40% of the control group reported worsening of seven symptoms over time (↓). Sleep disturbances, lack of energy, shaking hands, stiffness and clumsiness showed mixed results in improvement in the yoga group. Falling episodes had declined by 25% in the yoga group.

Table 2.

Self-report of symptoms and activity in the medical questionnaire

Yoga participants reported more energy and visible tremor reduction lasting several hours immediately following yoga plus more relaxation with less fatigue, positive social relationship building, improved overall mood and paying more attention to body signals. Two yoga group participants reported taking medications less frequently as symptoms were reduced.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to determine the potential effects of yoga on non-motor symptoms, specifically depression, QOL and physiological measures. Certain QOL and physiological measures resulted in improvement or maintenance in activity and exercise tolerance, suggesting that positive effects of yoga may be possible. Because of the progressive nature of PD, lack of deterioration of yoga participants' self-reported symptoms and improvement in clinical outcome measures suggest that yoga is potentially an effective intervention to maintain the current activity level. These results are consistent with studies of exercise-related benefits in PD.[7]

UPDRS scores were significantly improved, especially during the initial 6 weeks of yoga training. The 95% confidence intervals indicate that clinical benefit is likely to result from the intervention. Improvement in UPDRS scores could be explained by improved motor symptoms,[11] but it is possible that non-motor symptoms could cumulatively contribute to the score. Select improvements in QOL and physiology support a theory that yoga impacts multiple factors. Decreased falling episodes may link to the improved balance previously noted.[11] It is possible that with more participants, improvements would have been noted in other SF-36 domains or the group gender discrepancy could alter these perceptions. Our results resemble aerobic and strengthening exercise interventions where emotional reactions, social interactions, physical activity and QOL scores improve in PD participants.[6,7]

Depression has a major impact on the symptoms of PD[3] and is often overlooked and undertreated. Yoga practice shows improvements in memory, stress, depression and anxiety in a healthy population,[12] possibly due to improved cortisol levels.[13] People with chronic pain who participated in yoga demonstrate improvements in depression, anxiety, fatigue and pain,[14] while yoga in those with multiple sclerosis has a significant impact on QOL, fatigue and cognition.[8] Our results support the continued investigation of yoga for improving QOL in PD.

Our results of improved FVC after 6 weeks is consistent with another study showing that as little as 8 weeks of yoga in inactive older adults improves respiratory function, blood pressure and aspects of mental wellbeing.[15] Improvement in cardiorespiratory fitness, specifically pulmonary function parameters, rate of perceived exertion and exercise tolerance after aerobic exercise training has been reported in PD.[5]

The intensity of our yoga intervention seemed to have some effect on cardiopulmonary function. It is known that different types of yoga breathing techniques have different effects on blood pressure. Healthy participants increase absolute and relative maximal oxygen uptake in addition to improved strength and flexibility, showing health-related improvement in physical fitness.[16] Healthy elderly have improved maximum expiratory function and inspiratory pressures after yoga.[17] Our results support these findings and those that found improvements in blood pressure,[10] but changes in blood pressure may be confounded by the existence of multiple comorbidities and medications.

Yoga may contribute to efficacy via improvement in physiological and psychological variables associated with PD. A proposed mechanism of mental and physical health benefits has been postulated through the down-regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.[18] Differences in stress responses between novice and expert yoga practitioners allude to this pathway as having health benefits.[19] Psychological effects have been related to increased γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) activity. Improved mood with decreased anxiety was correlated with acute changes in thalamic GABA levels in a healthy yoga group, which was different than a metabolically matched walking group.[20] Studies are needed to confirm the psycho - neuro immunological hypotheses in neurological disease.

Given the pilot nature of this study, there are a number of limitations: Small sample size, coin toss randomization method, no control for social interaction, confounding variables like comorbidities, no correction for multiple comparisons between outcome measures and the measures selected may not have captured important changes in other relevant non-motor symptoms that might be positively impacted by yoga.

Yoga appears to improve physiological and non-motor factors that can affect QOL over a relatively short period of time for PD participants. It is important to determine conservative intervention to treat physiological functions and clinical outcomes contributing to QOL in PD for which yoga appears to be a viable intervention.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Suzette Scholtes for her expert yoga instruction, the staff at The Yoga Studio for their assistance during yoga intervention, statistician Wendy Hu for her consultation and review of SF36 statistical analysis and Jill Stanhope and Jessica Vandehoef for taking the UPDRS motor measures.

Footnotes

Source of Support: An internal grant from the KUMC School of Allied Health Research Committee to Yvonne (Searls) Colgrove supported the study. Physiological measure data collection was made possible by Grant Number M01 RR023940 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH)

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Péchevis M, Clarke CE, Vieregge P, Khoshnood B, Deschaseaux-Voinet C, Berdeaux G, et al. Trial Study Group. Effects of dyskinesias in Parkinson's disease on quality of life and health-related costs: A prospective European study. Eur J Neurol. 2005;12:956–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2005.01096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chapuis S, Ouchchane L, Metz O, Gerbaud L, Durif F. Impact of the motor complications of Parkinson's disease on the quality of life. Mov Disord. 2005;20:224–30. doi: 10.1002/mds.20279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schrag A. Quality of life and depression in Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Sci. 2006;248:151–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2006.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garber CE, Friedman JH. Effects of fatigue on physical activity and function in patients with Parkinson's disease. Neurology. 2003;60:1119–24. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000055868.06222.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Köseoðlu F, Inan L, Ozel S, Deviren SD, Karabiyikoðlu G, Yorgancioðlu R, et al. The effects of a pulmonary rehabilitation program on pulmonary function tests and exercise tolerance in patients with Parkinson's disease. Funct Neurol. 1997;12:319–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herman T, Giladi N, Gruendlinger L, Hausdorff JM. Six weeks of intensive treadmill training improves gait and quality of life in patients with Parkinson's disease: A pilot study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88:1154–8. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodrigues de Paula F, Teixeira-Salmela LF, Coelho de Morais Faria CD, Rocha de Brito P, Cardoso F. Impact of an exercise program on physical, emotional, and social aspects of quality of life of individuals with Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2006;21:1073–7. doi: 10.1002/mds.20763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oken BS, Kishiyama S, Zajdel D, Bourdette D, Carlsen J, Haas M, et al. Randomized controlled trial of yoga and exercise in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2004;62:2058–64. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000129534.88602.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Madanmohan, Mahadevan SK, Balakrishnan S, Gopalakrishnan M, Prakash ES. Effect of six weeks yoga training on weight loss following step test, respiratory pressures, handgrip strength and handgrip endurance in young healthy subjects. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2008;52:164–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pramanik T, Sharma HO, Mishra S, Mishra A, Prajapati R, Singh S. Immediate effect of slow pace bhastrika pranayama on blood pressure and heart rate. J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15:293–5. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colgrove Y, Sharma N, Kluding P, Potter D, Imming K, VandeHoef J, et al. Effect of Yoga on motor function in people with Parkinson's disease: A randomized, controlled pilot study. J Yoga Phys Ther. 2012;2:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rocha KK, Ribeiro AM, Rocha KC, Sousa MB, Albuquerque FS, Ribeiro S, et al. Improvement in physiological and psychological parameters after 6 months of yoga practice. Conscious Cogn. 2012;21:843–50. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2012.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vera FM, Manzaneque JM, Maldonado EF, Carranque GA, Rodriguez FM, Blanca MJ, et al. Subjective sleep quality and hormonal modulation in long-term yoga practitioners. Biol Psychol. 2009;81:164–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hennard J. A protocol and pilot study for managing fibromyalgia with yoga and meditation. Int J Yoga Therap. 2011;21:109–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vogler J, O’Hara L, Gregg J, Burnell F. The impact of a short-term iyengar yoga program on the health and well-being of physically inactive older adults. Int J Yoga Therap. 2011;21:61–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tran MD, Holly RG, Lashbrook J, Amsterdam EA. Effects of hatha yoga practice on the health-related aspects of physical fitness. Prev Cardiol. 2001;4:165–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1520-037x.2001.00542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Santaella DF, Devesa CR, Rojo MR, Amato MB, Drager LF, Casali KR, et al. Yoga respiratory training improves respiratory function and cardiac sympathovagal balance in elderly subjects: A randomised controlled trial. BMJ open. 2011;1:e000085. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kulkarni DD, Bera TK. Yogic exercises and health-a psycho-neuro immunological approach. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2009;53:3–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Christian L, Preston H, Houts CR, Malarkey WB, Emery CF, et al. Stress, inflammation, and yoga practice. Psychosom Med. 2010;72:113–21. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181cb9377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Streeter CC, Whitfield TH, Owen L, Rein T, Karri SK, Yakhkind A, et al. Effects of yoga versus walking on mood, anxiety, and brain GABA levels: A randomized controlled MRS study. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16:1145–52. doi: 10.1089/acm.2010.0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]