The permeant ion nitrate modulates CFTR gating to increase its open probability through a mechanism similar to that of VX-770.

Abstract

Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) is unique among ion channels in that after its phosphorylation by protein kinase A (PKA), its ATP-dependent gating violates microscopic reversibility caused by the intimate involvement of ATP hydrolysis in controlling channel closure. Recent studies suggest a gating model featuring an energetic coupling between opening and closing of the gate in CFTR’s transmembrane domains and association and dissociation of its two nucleotide-binding domains (NBDs). We found that permeant ions such as nitrate can increase the open probability (Po) of wild-type (WT) CFTR by increasing the opening rate and decreasing the closing rate. Nearly identical effects were seen with a construct in which activity does not require phosphorylation of the regulatory domain, indicating that nitrate primarily affects ATP-dependent gating steps rather than PKA-dependent phosphorylation. Surprisingly, the effects of nitrate on CFTR gating are remarkably similar to those of VX-770 (N-(2,4-Di-tert-butyl-5-hydroxyphenyl)-4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxamide), a potent CFTR potentiator used in clinics. These include effects on single-channel kinetics of WT CFTR, deceleration of the nonhydrolytic closing rate, and potentiation of the Po of the disease-associated mutant G551D. In addition, both VX-770 and nitrate increased the activity of a CFTR construct lacking NBD2 (ΔNBD2), indicating that these gating effects are independent of NBD dimerization. Nonetheless, whereas VX-770 is equally effective when applied from either side of the membrane, nitrate potentiates gating mainly from the cytoplasmic side, implicating a common mechanism for gating modulation mediated through two separate sites of action.

INTRODUCTION

Ion channels are integral membrane proteins ubiquitously expressed in every cell. Serving as a major route for ion movement across the cell membrane, they are equipped with the capability to discriminate between different ion species. It is this unique property of ion selectivity, together with a fast throughput rate, that enables the channel proteins to enact a variety of physiological functions (Hille, 2001). Because of a fast ion conduction through the pore, an ion channel also needs to undergo conformational changes that confer a fine control of the patency of the channel (i.e., opening/closing of the gate or gating). Despite the traditional view of ion permeation and gating as two separate processes, a wealth of recent studies provides compelling evidence that the same structural components in a channel can execute both functions (Liu et al., 1997; Liu and Siegelbaum, 2000; Contreras et al., 2008). At one extreme, gating and permeation are in fact tightly coupled. Take the CLC-0 chloride channel as an example; it is fairly established that a negatively charged glutamate residue at the external entrance of the pore actually serves as the gate (Dutzler et al., 2003), and that the competition between the permeating Cl− and the carboxyl group of this glutamate for an anion-binding site in the pore constitutes the fundamental basis for permeation-gating coupling (Chen, 2003; Feng et al., 2010, 2012).

CFTR, a member of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) protein superfamily, is a phosphorylation-activated but ATP-gated anion channel (Sheppard and Welsh, 1999; Gadsby et al., 2006; Hwang and Sheppard, 2009). Loss-of-function mutations of the CFTR gene cause cystic fibrosis, a lethal genetic disease most commonly afflicting people of Caucasian origins (Riordan et al., 1989). Like other anion channels, CFTR’s pore is promiscuous and permeable to a host of anions such as chloride, bromide, nitrate, iodide, and bicarbonate, but the conductance, measured from the slope of an I-V relationship, and the permeability ratio, calculated from the shift of the reversal potential, differ among these anions. For example, previous studies (Linsdell and Hanrahan, 1998; Dawson et al., 1999; Smith et al., 1999; Linsdell et al., 2000; Linsdell, 2001) of the CFTR pore have shown a permeability sequence of SCN− > I− > NO3− > Br− > Cl− > F−, but a conductance sequence of Cl− > NO3− > Br− ≥ formate > F− > SCN− ≈ ClO4−. Based on the biophysical characteristics of anion permeation, Dawson et al. (1999) envision a CFTR pore composed of an outer- and an inner-electropositive vestibule directing the bulk anions to the narrow region of the pore, which acts as a dielectric tunnel without the need of a well-crafted selectivity filter.

Gating of the CFTR chloride channel is of interest in its own right. Because of the evolutionary relationship between CFTR and exporter members of the ABC protein superfamily (Gadsby et al., 2006; Chen and Hwang, 2008), CFTR likely harnesses the free energy of ATP binding and hydrolysis in its conserved nucleotide-binding domains (NBDs) to power the conformational changes of the transmembrane domains (TMDs) that make up a gated pore. Although the exact conformational changes in CFTR gating remain unclear, abundant experimental evidence supports the idea that opening and closing of the gate in CFTR’s TMDs are coupled, respectively, to ATP binding–induced dimerization and hydrolysis-catalyzed partial separation of the NBDs (Tsai et al., 2009, 2010; Szollosi et al., 2011). Although earlier studies champion the hypothesis that each opening and closing cycle of the gate is strictly coupled to the ATP hydrolysis cycle (Baukrowitz et al., 1994; Hwang et al., 1994; Gunderson and Kopito, 1995; Zeltwanger et al., 1999; Csanády et al., 2010), our recent reports propose a gating model featuring energetic coupling between gating motions in the TMDs and association/dissociation of the NBDs (Jih and Hwang, 2012; Jih et al., 2012a,b). This relatively new idea not only loosens the coupling stoichiometry of CFTR gating by ATP but also implicates a more autonomous role of TMDs in gating conformational changes (Jih and Hwang, 2012). Indeed, cysteine-scanning studies of CFTR’s TMDs have revealed that mutations or/and chemical modifications of the pore-lining residues can drastically affect ATP-dependent and -independent gating (Bai et al., 2010, 2011; Gao et al., 2013). In light of the evolutionary relationship between CFTR and ABC transporters, which undergo large-scale conformational changes in their TMDs during each transport cycle (Rees et al., 2009), it is perhaps not surprising that CFTR’s pore architecture may differ markedly between the open and closed states (e.g., Bai et al., 2010, 2011).

In the current studies aimed originally at characterizing the permeation properties of CFTR’s pore, we accidentally found that permeant ions can affect CFTR gating. Specifically, both Br− and NO3−, when applied to the cytoplasmic side of the channel, increase the open probability (Po) of CFTR. Because the effect of NO3− is much larger, we performed a series of experiments to unveil the mechanism underpinning gating modulation by NO3−. Interestingly, despite very different physicochemical properties between NO3− and VX-770 (Ivacaftor or Kalydeco), a well-characterized CFTR potentiator (Jih and Hwang, 2013), they share remarkable similarities in gating modulation. These include single-channel kinetics; deferral of nonhydrolytic gate closure; and potentiation of a disease-associated mutation, G551D. However, when NO3− and VX-770 were applied together, a pure additive effect was seen, suggesting that these two reagents work independently to enhance CFTR activity. The possible action site for NO3− was narrowed down by showing positive gating modulation on the CFTR constructs with the R domain or NBD2 removed (i.e., ΔR- or ΔNBD2-CFTR).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and transfection

Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells were grown at 37°C in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Cells were subcultured into 35-mm tissue culture dishes 1 d before transfection. PolyFect transfection reagent (QIAGEN) was used to cotransfect CFTR cDNA and pEGFP-C3 (Takara Bio Inc.), which encodes green fluorescence proteins, into CHO cells. After transfection, cells were incubated at 27°C for at least 2 d before electrophysiological experiments were performed.

Mutagenesis

QuikChange XL kit (Agilent Technologies) was used for site-directed mutagenesis according to the manufacturer’s protocols to construct all the CFTR mutants used in this study. All of the DNA constructs were sequenced by the DNA Core Facility (University of Missouri) to confirm the mutation made.

Electrophysiological recordings

Glass chips carrying the transfected cells were transferred to a chamber located on the stage of an inverted microscope (IX51; Olympus). Borosilicate capillary glasses were used to make patch pipettes using a two-stage micropipette puller (PP-81; Narishige). The pipettes were polished with a homemade microforge to a resistance of 2–4 MΩ in the bath solution. Once the seal resistance reached >40 GΩ, membrane patches were excised into an inside-out mode. Subsequently, the pipette was moved to the outlet of a three-barrel perfusion system and perfused with 25 IU PKA and 2 mM ATP until the CFTR current reached a steady state. Because of the existence of membrane-associated phosphatases in excised inside-out patches, to maintain the phosphorylation level of the CFTR channels, all ATP-containing solutions were supplemented with ∼6 IU PKA. A patch-clamp amplifier (EPC10; HEKA) was used to record electrophysiological data at room temperature. The data were filtered online at 100 Hz with an eight-pole Bessel filter (LPF-8; Warner Instruments) and digitized to a computer at a sampling rate of 500 Hz. Solution changes were effected with a fast solution change system (SF-77B; Warner Instruments) that has a dead time of ∼30 ms (Tsai et al., 2009). For macroscopic current recordings, the membrane potential (Vm) was held at −30 mV. To obtain macroscopic I-V relationships, voltage ramps (−100 to 70 mV over a duration of 1 s) were applied. Vm = −50 mV for single-channel recordings unless noted otherwise.

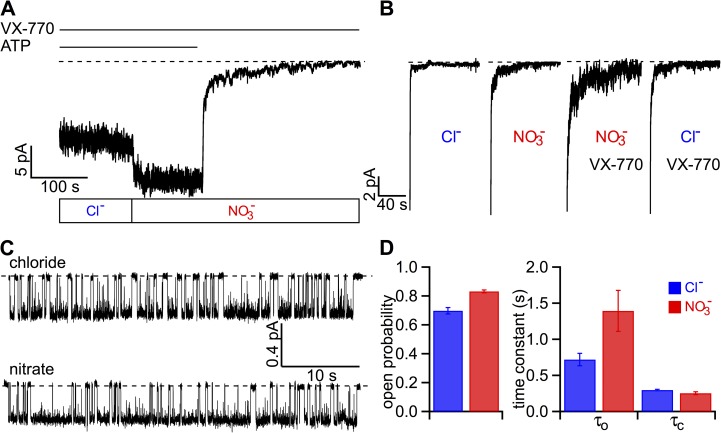

Notably, the effect of VX-770 cannot be washed out by continuously perfusing a VX-770–free solution within the experimentally permissible time. We therefore could not carry out “bracketed” experiments with this reagent. As a result, most of the experiments with VX-770 were done after first obtaining a control in the same patch (e.g., Fig. 8). Furthermore, to minimize contamination by any residual VX-770, all devices that had been in contact with VX-770 were repeatedly washed with 50% DMSO before carrying out the next experiment.

Figure 8.

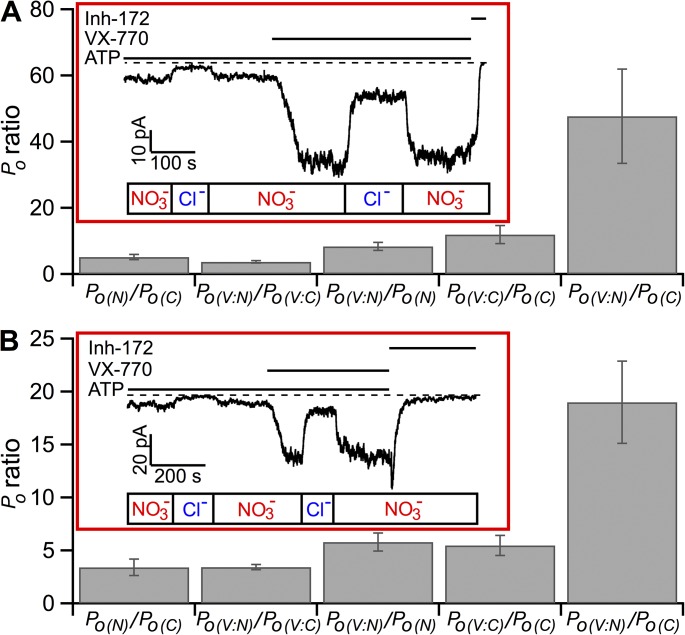

NO3− and VX-770 potentiate ΔNBD2- and G551D-CFTR in an independent manner. (A) Quantitative assessments of the effect of NO3− and VX-770 on ΔNBD2-CFTR’s activity. The current trace shown in the inset represents the standard protocol that allows us to calculate the ratios of mean current amplitudes for each treatment as labeled. A specific CFTR inhibitor, Inh-172, was applied at the end of each experiment to attain the baseline. These ratios were converted to ratios of Po by correcting differences in single-channel amplitudes (see Materials and methods for detail). The bar chart summarizes these results. Po(N), Po in NO3− bath; Po(C), Po in Cl− bath; Po(V:N), Po in NO3− bath with VX-770; Po(V:C), Po in Cl− bath with VX-770. (B) Independent potentiation of G551D-CFTR by NO3− and VX-770. The current trace in the inset illustrates the results of G551D-CFTR channels under the same experimental protocol shown in A. Summary of the Po ratios obtained as described above. The error bars represent the SEM of the mean.

Chemicals and solution compositions

For recordings in excised inside-out patches, we used the pipette solution containing (mM): 140 methyl-d-glucamine chloride (NMDG-Cl), 5 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, and 10 HEPES, pH 7.4 with NMDG. Before patch excision, cells were perfused with a bath solution containing (mM): 145 NaCl, 2 MgCl2, 5 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 5 glucose, 5 HEPES, and 20 sucrose, pH 7.4 with NaOH. After patch excision, the pipette was bathed in a perfusion solution containing (mM): 150 NMDG-Cl, 2 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 10 EGTA, and 8 Tris, pH 7.4 with NMDG. For anion substitution experiments, NMDG-Cl in the inside-out perfusion solution was replaced with NMDG-NO3 or NMDG-Br. For experiments using nitrate as the major anions in the pipette solution, 4 mM chloride was added to ensure proper function of the recording Ag/AgCl electrode, and the rest of the solution remained the same as the chloride pipette solution, except NMDG-Cl was substituted by NMDG-NO3.

Pyrophosphate (PPi), MgATP, and PKA were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. PPi and MgATP were stored in 200- and 250-mM stock solutions, respectively, at −20°C. VX-770, provided by R. Bridges (Rosalind Franklin University, North Chicago, IL), was dissolved in DMSO and stored as a 100-µM stock at −70°C. All chemicals were diluted to the concentration indicated in each figure using the perfusion solution, and the pH was adjusted to 7.4 with NMDG.

Data analysis and statistics

For analysis of macroscopic currents, the Igor Pro program (WaveMetrics) was used to compute the steady-state mean current amplitude as well as to execute curve fitting of the current decay upon removal of ATP to obtain the relaxation time constants. The permeability ratio between two different charge carriers under bi-ionic condition is calculated from the shift of the reversal potential using the Goldman–Hodgkin–Katz equation,

where x− represents substituting anions for Cl−, and R, T, and F have their usual thermodynamic meanings.

Single-channel kinetic analysis for traces that contains fewer than three opening steps was done with a program developed by Csanády (2000). Single-channel amplitudes were measured from all-point histograms generated with Igor Pro. All results were presented as means ± SEM; n represents the number of experiments. Student’s paired or two-tailed t test was performed with Excel (Microsoft). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

To test the hypothesis that NO3− and VX-770 may interact, we examined quantitatively the effects of these two reagents in the same patch (hence the same number of channels) containing ΔNBD2- or G551D-CFTR (Fig. 8). As these two mutant channels likely no longer hydrolyze ATP, their gating mechanism, contrary to that of WT-CFTR, can be described—in a simplistic manner—as two-state transitions in equilibrium (Fig. 10). Because the Po of these two mutants is exceedingly low, the formula of Po can also be simplified to ko/kc; ko and kc: opening rate and closing rate, respectively. We measured, in the same patch, the macroscopic current amplitudes in the presence of NO3−, VX-770, or NO3− plus VX-770 to calculate fold increase by each maneuver based on the ratio of the current amplitudes estimated in each of the experimental conditions (Fig. 8). The ratios of these macroscopic current amplitudes can be converted to the ratios of Po once the difference in single-channel amplitudes between Cl− and NO3− as charged carriers is corrected based on the single-channel I-V curves shown in Fig. 2.

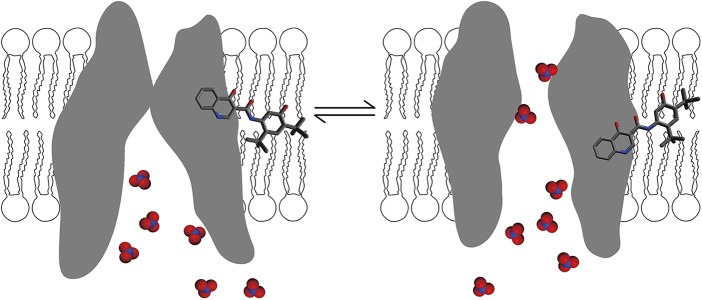

Figure 10.

A cartoon depicting possible mechanisms for the independent gating modulation by NO3− and VX-770. Because our intention is to elaborate the experimental results shown in Fig. 8 with ΔNBD2- and G551D-CFTR, in this simplified scheme, a closed state (left) and an open state (right) are portrayed as in equilibrium. The hydrophobic VX-770, by partitioning into the lipid bilayer, acts on CFTR’s TMDs at the interface between the channel protein and membrane lipids. In contrast, nitrate ions interact with the channel at the water–protein interface. By acting through different interfaces, NO3− and VX-770 can perturb the free energy levels of both open and closed states independently. As a result, the free energy changes by NO3− plus VX-770 on gating will be the sum of the free energy alterations by individual molecules.

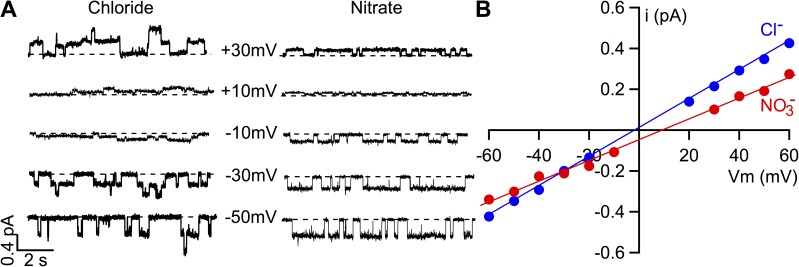

Figure 2.

Comparisons of permeability and conductance of microscopic CFTR currents between Cl− and NO3−. (A) Representative single-channel CFTR current traces at different membrane potentials in the presence of bath Cl− or NO3− containing 2 mM ATP. These single-channel data were obtained from two different patches, and hence the number of channels is not the same. The apparent inconsistent activity in Cl− bath at different voltages is probably caused by partial dephosphorylation of the channel during prolonged recording. (B) Single-channel I-V relationships with bath Cl− or NO3−. The reversal potential in this microscopic I-V curve is shifted to a positive voltage when bath Cl− is replaced by NO3−. In contrast to the difference in macroscopic CFTR conductance shown in Fig. 1 B, single-channel conductance in bath NO3− is lower than that in Cl−.

The transition-state theory of reaction rates allows the following mathematical derivations to obtain free energy (G) perturbations of gating modulation for NO3−, VX-770, or NO3− plus VX-770:

where

Then,

Similarly,

Thus,

From the deduction above, we can conclude that NO3− and VX-770 should work in an energetically additive manner without any interaction when the Po ratio under the effects of both compounds is the product of the Po ratios from effects of individual reagents. That is,

RESULTS

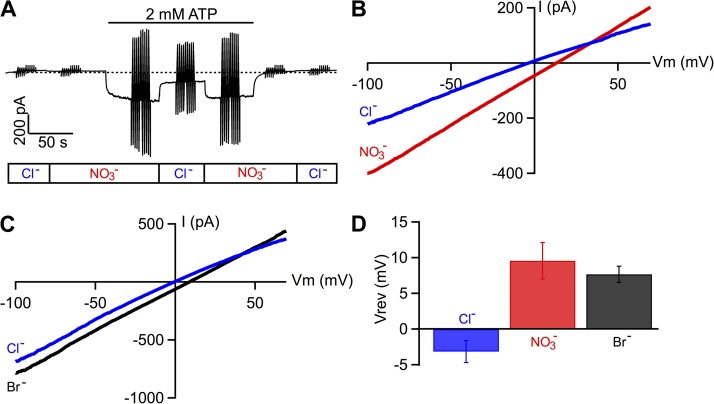

Previous studies on anion permeation of CFTR at the single-channel level have demonstrated a selectivity sequence of > > , but > > (Linsdell and Hanrahan, 1998; Dawson et al., 1999; Smith et al., 1999; Linsdell et al., 2000; Linsdell, 2001). As a first step to characterize the anion permeation properties for CFTR’s pore, we performed similar experiments with macroscopic WT CFTR currents in an attempt to duplicate these results. We confirmed the permeability sequence of > > , but to our surprise, the conductance measured from macroscopic I-V relationships shows the same selectivity sequence among these three anions.

Fig. 1 A shows a representative experiment that compares Cl− and NO3− as charge carriers for WT-CFTR channels prephosphorylated by PKA and ATP. In the absence of ATP, replacing bath Cl− with NO3− caused little change of the baseline current amplitude. At a holding potential of −30 mV, subsequent application of ATP in NO3− induced an inward current that was significantly decreased once the bath NO3− was replaced with Cl−. This current reduction could be completely recovered by changing the charge carrier to NO3− again. The I-V relationships obtained from voltage ramp protocols (vertical lines in Fig. 1 A) reveal two pertinent biophysical properties. First, the reversal potential in NO3− is shifted to the right compared with that in Cl− (Fig. 1 B), resulting in a permeability ratio / of 1.85 ± 0.03 (n = 3). Second, macroscopic conductance, calculated from the slope of the I-V curves, shows clearly > (/ = 1.59 ± 0.01). When anion substitution experiments were performed with Cl− and Br−, a similar rightward shift of the reversal potential and an increase of macroscopic conductance were observed (Fig. 1 C; / = 1.43 ± 0.02 and / = 1.22 ± 0.05; n = 3). Fig. 1 D summarizes the results of reversal potential measurements: Vrev of NO3−, Br−, and Cl− were 9.58 ± 2.55 mV (n = 3), 7.68 ± 1.14 mV (n = 3), and −3.15 ± 1.55 mV (n = 6), respectively, indicating a selectivity sequence of > > .

Figure 1.

Comparisons of permeability and conductance ratios of macroscopic WT-CFTR currents among Cl−, Br−, and NO3−. (A) A real-time recording of macroscopic CFTR current showing the effect of cytoplasmic substitutions of anionic charge carriers. CFTR channels were preactivated by PKA-dependent phosphorylation. At a holding potential of −30 mV, the application of ATP in NO3− bath elicits an inward current, which is significantly reduced upon replacement of NO3− with Cl−, as marked in the rectangular box below the current trace. The vertical lines in A are current fluctuations that resulted from the voltage ramps. (B) Macroscopic I-V relationships for net CFTR conductance in the presence of bath Cl− or NO3−. Net CFTR currents were obtained by subtracting the current in the absence of ATP from ATP-induced current. (C) Macroscopic I-V relationships for CFTR conductance in the presence of bath Cl− or Br−. These I-V curves were obtained from an experiment similar to the one depicted in A. (D) Summary of the reversal potential values in different baths as indicated. The error bars represent the SEM of the mean.

The unexpected results of > > prompted us to test the idea that these permeant anions may affect CFTR gating. If there were any gating effect by replacing bath Cl−, the action of NO3− would be much larger than that of Br−; therefore, we decided to focus our efforts on NO3−. We first examined single-channel I-V relationships to confirm previous reports on differences of single-channel conductance (g) between Cl− and NO3− (i.e., > ). Fig. 2 A shows single-channel traces of WT-CFTR in excised inside-out patches at different holding potentials in the presence of bath Cl− or NO3−. The resulting I-V relationships (Fig. 2 B) disclose a conductance ratio / of 0.69 ± 0.02 (n = 4), which is consistent with previous reports (Linsdell, 2001) but very different from the results based on macroscopic measurements (Fig. 1 B).

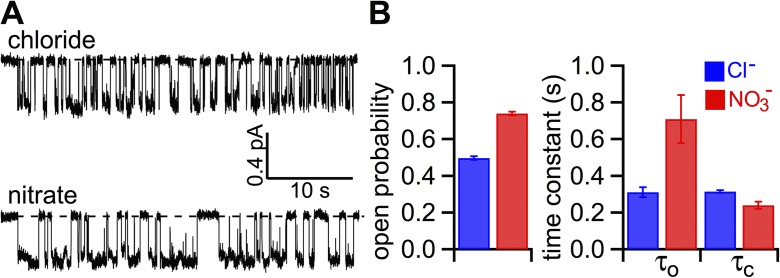

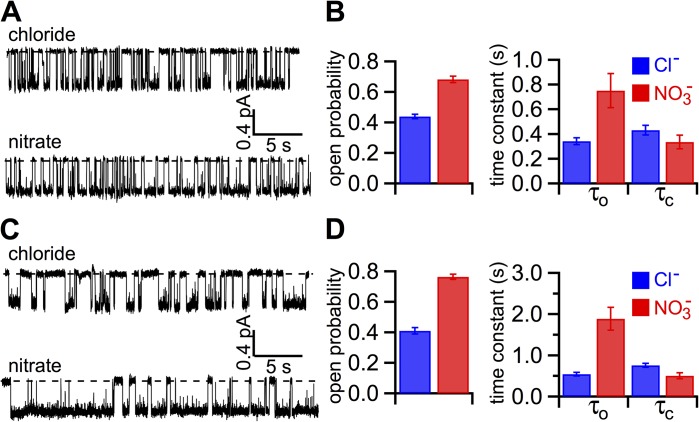

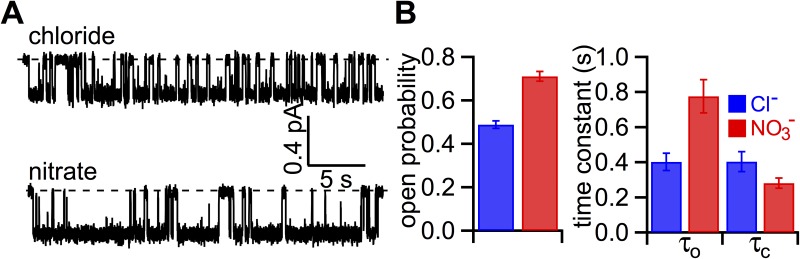

Because the macroscopic I-V curves shown in Fig. 1 B were obtained from the same patch, the number of active channels should be constant regardless of the charge carrier. Thus, the difference between macroscopic and microscopic conductance ratios must be caused by a positive effect of NO3− on the Po. In support of this idea, Fig. 3 A shows representative single-channel traces with Cl− or NO3− as the charge carrier. It appears that the open time is longer and the closed time is slightly shorter with NO3− in the bath. Single-channel kinetic analysis indeed confirms an increase of the Po by NO3− (0.74 ± 0.02 and 0.50 ± 0.01 in NO3− and Cl−; n = 4; P < 0.005). Fig. 3 B summarizes the single-channel parameters. Although the opening rate in the presence of NO3− is slightly increased, NO3− considerably prolongs the open time from 311 ± 27 ms to 709 ± 132 ms (n = 4; P < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Effect of cytoplasmic replacement of Cl− with NO3− on WT-CFTR gating. (A) Single-channel current traces of WT-CFTR in the presence of bath Cl− or NO3−. CFTR in an inside-out patch was activated by PKA and ATP before the bath solution was switched to one with 2 mM ATP in Cl− or NO3−. Holding potential, −50 mV. (B) Single-channel kinetic parameters of WT-CFTR in the presence of bath Cl− or NO3−. Po, open time constant (τo), and closed time constant (τc): 0.50 ± 0.01, 311 ± 27 ms, and 315 ± 7 ms for Cl−; and 0.74 ± 0.02, 709 ± 132 ms, and 240 ± 19 ms for NO3− (n = 4). The error bars represent the SEM of the mean.

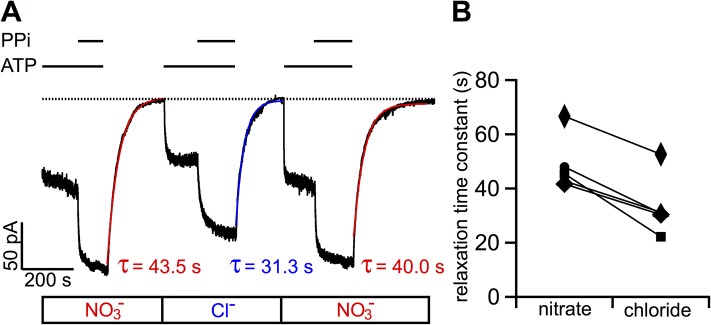

So far, our results have demonstrated that NO3−, as a permeant ion, can significantly affect WT-CFTR gating mainly by lengthening the open time. It is generally accepted that the opening of WT-CFTR’s gate is associated with ATP-induced dimerization of its NBDs (NBD1 and NBD2), whereas gate closure is triggered by ATP hydrolysis that facilitates a partial separation of the NBD dimer (Jih and Hwang, 2012). Thus, a simple mechanism for NO3− to prolong CFTR’s open time is to inhibit ATP hydrolysis, a hypothesis we should contemplate more seriously because, unlike conventional organic CFTR potentiators (Hwang and Sheppard, 1999), NO3− is relatively small such that it could potentially be accommodated at the NBD dimer interface where ATP hydrolysis occurs. We therefore asked if NO3− can also prolong the open time when ATP hydrolysis is abolished. To test this idea, we compared the relaxation time constant upon removal of ATP once the WT-CFTR channels were locked in an open state by ATP and PPi (Gunderson and Kopito, 1994; Tsai et al., 2009). Fig. 4 A shows an example of such experiments: once WT-CFTR channels were activated by PKA and ATP in NO3− bath, the current could be further increased by the addition of 4 mM PPi. The current decay upon the removal of ATP and PPi follows a very slow time course, which can be well fitted with a single-exponential function with a relaxation time constant of 49.2 ± 4.9 s (n = 5). In the same patch, the same experimental procedure performed in Cl− bath resulted in a significantly shorter relaxation time constant of 32.0 ± 4.0 s (P < 0.005). The lengthening of the relaxation time constant by NO3− was also seen with a hydrolysis-deficient mutant, E1371S-CFTR (n = 5). The relaxation time constant in NO3− is 164.7 ± 27.3 s, but the time constant was significantly shorter in Cl− bath (100.7 ± 49.4 s; P < 0.05). We thus conclude that the effect of NO3− on WT-CFTR gating is not likely caused by a disruption of ATP hydrolysis (also see Fig. 5, C and D, below).

Figure 4.

NO3− prolongs the relaxation time constant of WT-CFTR channels locked in an open state by ATP plus PPi. (A) A continuous current recording of WT-CFTR channels demonstrating lengthening of the relaxation time by NO3−. Macroscopic CFTR currents were activated by PKA and 1 mM ATP to a steady state (not depicted), and then the application of 4 mM PPi in the continued presence of ATP resulted in further current rise as the channels were locked open by PPi. The resulting current decreased slowly after subsequent removal of ATP and PPi in NO3− bath, yielding a relaxation time constant (τrel) of 43.5 s. A similar protocol with bath Cl− performed in the same patch shows a much faster current decay upon washout of ATP and PPi (τrel = 31.3 s). Red line and blue line represent fits of the current decay with a single-exponential function. (B) Summary of the relaxation time constants for PPi locked-open CFTR channels. Because each pair of the time constants was obtained from experiments depicted in A, the shortening of τrel by Cl− in each patch is demonstrated by a straight line linking individual paired time constants.

Figure 5.

Effects of NO3− on single-channel kinetics of ΔR-CFTR and D1370N/ΔR-CFTR. (A) Modulation of ΔR-CFTR gating by NO3−. Because the activity of ΔR-CFTR is independent of phosphorylation, only ATP is included in the bath. (B) Summary of the effect of NO3− on the single-channel kinetics of ΔR-CFTR. Po, τo, and τc: 0.44 ± 0.02, 342 ± 28 ms, and 432 ± 39 ms for Cl−; and 0.68 ± 0.02, 751 ± 138 ms, and 336 ± 55 ms for NO3− (n = 15). (C) NO3− increases the Po of a hydrolysis-deficient mutant CFTR (D1370N). (D) Microscopic kinetic parameters for D1370N/ΔR-CFTR in the presence of bath Cl− or NO3−. Po, τo, and τc: 0.41 ± 0.02, 544 ± 45 ms, and 759 ± 48 ms for Cl−; and 0.77 ± 0.02, 1,889 ± 278 ms, and 508 ± 71 ms for NO3− (n = 10). The error bars represent the SEM of the mean.

Besides being a permeant ion, as a water-soluble molecule, NO3− may interact with different parts of the CFTR channel that are exposed in the hydrophilic environment (i.e., cytosolic domains of CFTR). We first consider the R domain as a potential target for two reasons. First, it is known that different levels of phosphorylation in the R domain affect CFTR gating. For reasons described previously (Lin et al., 2014; also see Materials and methods), we added PKA in all of our ATP-containing solutions. It is thus possible that the gating effect is secondary to an enhanced phosphorylation in the R domain by NO3−. Second, it has been shown (Cotten and Welsh, 1997) that covalent modification of cysteine 832 in the R domain increases the Po by shortening the closed time and prolonging the open time, similar to the kinetic effects observed with NO3−. We thus examined the effect of NO3− on a CFTR construct whose R domain was deleted (i.e., ΔR-CFTR; Csanády et al., 2000; Bompadre et al., 2005). Representative single-channel recordings of ΔR-CFTR in NO3− or Cl− bath are shown in Fig. 5 A. Fig. 5 B summarizes resulting microscopic kinetic data, which are remarkably similar to those obtained with WT-CFTR (Fig. 3 B). This result is important not only because it allows us to conclude that NO3− does not work on the R domain to exert its gating effect on CFTR; the fact that ΔR-CFTR, perhaps because of an inefficient assembly, affords a much easier collection of microscopic recordings for single-channel kinetic analysis also suggests to us that this construct can be a convenient tool to further our studies of the underlying mechanism for the gating effect of NO3−. To this end, we introduced the D1370N mutation into the ΔR background and characterized gating kinetics in the presence of NO3− or Cl− (Fig. 5 C). This conserved aspartate plays a critical role in coordinating Mg2+, an essential cofactor for ATP hydrolysis. Indeed, previous studies by Csanády et al. (2010) elegantly demonstrated that neutralizing this crucial aspartate residue abrogates the characteristic nonequilibrium gating of CFTR presumably caused by an abolition of ATP hydrolysis. Comparing the single-channel kinetic parameters of D1370N-CFTR further confirms that the effect of NO3− on both the opening rate and the closing rate is independent of ATP hydrolysis.

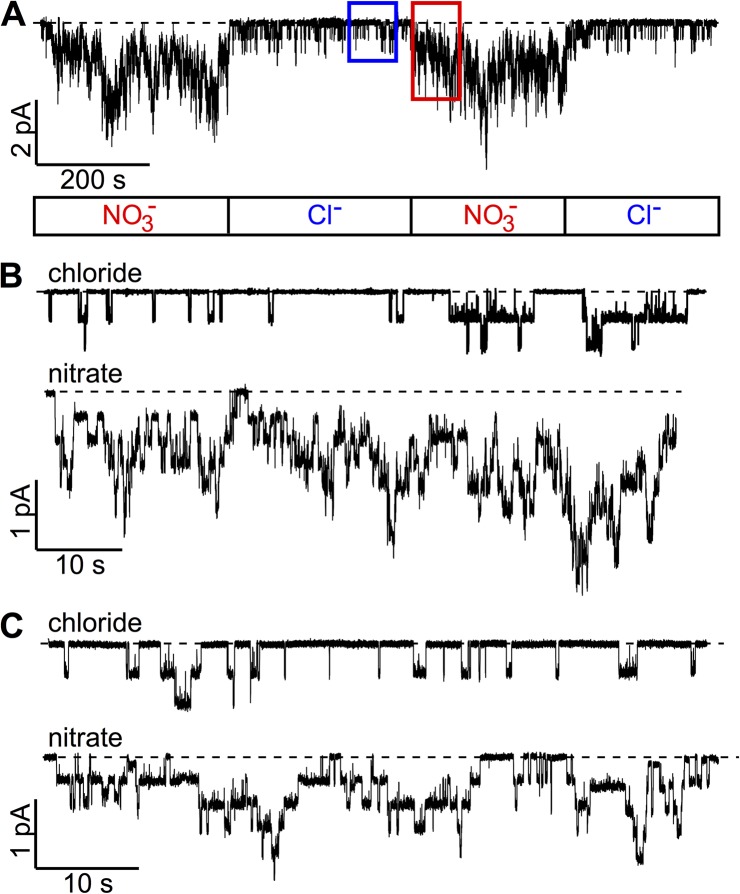

Once the involvement of ATP hydrolysis for the gating effect of NO3− is excluded, we next considered the possibility that NO3− prolongs the open time by stabilizing the open channel conformation. Our current understanding of the structural mechanism of CFTR gating (Jih and Hwang, 2012) portends that in addition to the effect of ATP hydrolysis described above, CFTR’s open time can also be increased by stabilization of the NBD dimer or/and the open pore configuration of the TMDs. To test if NBD dimerization is involved in the gating effect of NO3−, we applied NO3− to the cytoplasmic side of the ΔNBD2-CFTR channel, a construct with the NBD2 deleted and hence unresponsive to ATP (Cui et al., 2007; unpublished data). Fig. 6 A shows a real-time recording of ΔNBD2-CFTR channel currents in the presence of Cl− or NO3−. A large increase of the channel activity immediately upon switching the perfusion solution from one with Cl− to one with NO3− can be readily discerned. Fig. 6 B shows expanded traces from Fig. 6 A to offer a more detailed view of each opening/closing event. Quantitative analysis reveals a Po ratio of NO3− versus Cl−, Po(N)/Po(C) = 5.67 ± 0.90 (n = 9) at a holding potential of −50 mV. Semiquantitative analysis of these microscopic data also suggests that the gating effects of NO3− are caused by an increase of both the opening rate and the open time (see legend to Fig. 6). Although we cannot completely exclude the possibility that NBD dimerization still contributes to the gating effect of NO3− on WT-CFTR, this result indicates that NBD dimerization is not absolutely required for NO3− to lengthen the open time.

Figure 6.

NO3− enhances the activity of CFTR mutants with defective gating. (A) A continuous current trace showing an increase of channel activity of ΔNBD2-CFTR by NO3−. ΔNBD2-CFTR currents were first activated by PKA and ATP to a steady state before applying 2 mM ATP in Cl− or NO3− bath (marked in the box below the trace). (B) Expanded current traces from A (specified with red and blue rectangular boxes) to better discern each opening/closing event. Although accurate microscopic kinetic analysis cannot be attained, we carry out semiquantitative analysis for nine similar recordings by counting the number of opening events within a fixed time of ∼80 s in the same patch to roughly estimate the rate of opening in Cl− or NO3−. The resulting increase of the rate of opening by NO3− (2.48 ± 0.22–fold; n = 9) is much smaller (P < 0.01) than the fold increase of Po (5.67 ± 0.90; n = 9), indicating a simultaneous lengthening of the open time by NO3−. (C) Potentiation of G551D-CFTR gating by NO3−. Similar analysis of the rate of opening described in B was performed. In five patches, the fold increase of the rate of opening (2.19 ± 0.25; n = 5) is again significantly smaller (P < 0.05) than the magnitude of increase in Po (3.75 ± 0.86; n = 5).

Besides ΔNBD2-CFTR, our latest studies (Lin et al., 2014) also indicate that the pathogenic mutation G551D (i.e., replacement of the conserved glycine in the signature sequence of NBD1 with an aspartate) causes severe gating defects by preventing the formation of a prototypical NBD dimer caused by an electrostatic repulsion between the negatively charged γ-phosphate in ATP and the side chain of aspartate. Thus, the G551D-CFTR offers another opportunity to test the idea that NO3− can affect CFTR gating independently of NBD dimerization without resorting to a more drastic manipulation of CFTR by deleting its entire NBD2. Fig. 6 C shows an example of such experiments. NO3− indeed increases the Po of G551D channels by approximately fourfold (Po(N)/Po(C) = 3.75 ± 0.86; n = 5). Moreover, kinetically, NO3− also boosts the Po of G551D-CFTR by increasing the opening rate and decreasing the closing rate (see legend to Fig. 6).

This result with the G551D mutant not only corroborates data with the ΔNBD2-CFTR but also reveals an intriguing similarity between NO3− and a well-studied CFTR potentiator, VX-770 (Van Goor et al., 2009; Eckford et al., 2012; Jih and Hwang, 2013; Kopeikin et al., 2014), which is now used to treat cystic fibrosis patients carrying the G551D mutation. In addition to a potentiation of the G551D-CFTR as well as ΔNBD2-CFTR channels (see Fig. 8 below), NO3− and VX-770 share several qualitative similarities in their effects on CFTR gating. They both increase the Po of WT-CFTR by increasing the opening rate but decreasing the closing rate (Jih and Hwang, 2013). Like VX-770 (Kopeikin et al., 2014), NO3− slows down nonhydrolytic closing (Figs. 4 and 5 D).

Considering the drastic differences in physicochemical properties between VX-770 and NO3−, we were quite surprised by these similarities and decided to investigate if these two reagents may somehow interact with each other. We reasoned that if they work through different binding site(s), once the channel is maximally potentiated by VX-770, NO3− should pose additional effects. Fig. 7 A shows a continuous recording of macroscopic WT-CFTR currents in the presence of VX-770. Once the bath Cl− is replaced by NO3−, a further increase of the current is clearly discernable. Similarly, when the WT-CFTR channels were first potentiated by NO3−, the application of VX-770 further enhanced the current as well (not depicted). These macroscopic experiments also offer an opportunity to examine if VX-770 and NO3− pose additive effects on “ATP-independent” gating, defined as channel activity after ATP is removed from the bath. This residual CFTR channel activity after ATP removal is so high for the channels maximally potentiated by VX-770 plus NO3− that a discernable slow second phase of current decay can be seen. To compare the effects of VX-770 and NO3− on ATP-independent gating, current decays from the same patch under different conditions as marked are presented in Fig. 7 B. It is noted that when ATP is removed in Cl− before the application of VX-770, little activity is left at the end of the fast current decay. In contrast, significant residual currents are observed for currents potentiated by either VX-770 or NO3−. Of particular note, this ATP-independent CFTR activity is visibly higher in the presence of both VX-770 and NO3−. Similar observations were made in eight patches. We therefore conclude that like VX-770 (Eckford et al., 2012; Jih and Hwang, 2013), NO3− enhances ATP-independent gating and that this effect of VX-770 and NO3− appears to be additive. Fig. 7 C shows single-channel traces demonstrating a further increase in the Po of VX-770–treated WT-CFTR by NO3−. Kinetic analysis reveals that NO3− raises the already increased opening rate and open time, conferring an ultimate Po of >0.8 with a mean open time >1 s!

Figure 7.

Additive effects of NO3− and VX-770 on WT-CFTR gating. (A) NO3− further increases macroscopic WT-CFTR current in the presence of VX-770. Replacing bath Cl− with NO3− enhances the PKA-phosphorylated WT-CFTR current in the presence of VX-770. (B) A comparison of residual currents in the same patch after removal of ATP in different conditions as indicated. These “ATP-independent” activities are negligibly small in Cl− bath before the application of VX-770. On the other hand, more prominent channel currents are seen in NO3− bath. A similar increase of this ATP-independent activity by VX-770 was reported previously (Jih and Hwang, 2013; Lin et al., 2014). It is noted that a much higher current of VX-770–treated CFTR remains after ATP washout in NO3− bath. (C) Single-channel behavior of VX-770–potentiated WT-CFTR in Cl− or NO3− bath. Comparing these two 40-s traces, we noted longer open events and shorter closed events in NO3−. (D) Summary of the additive effect of NO3− and VX-770 on single-channel kinetics of WT-CFTR. Po, τo, and closed time τc are as follows: 0.70 ± 0.02, 720 ± 85 ms, and 299 ± 10 ms for Cl−; and 0.83 ± 0.02, 1,394 ± 283 ms, and 254 ± 20 ms for NO3− (n = 5). The error bars represent the SEM of the mean.

The results in Fig. 7 suggest that VX-770 and NO3− modulate CFTR gating in an additive manner, but two technical hurdles prohibit more quantitative assessments of this pharmacological idea. First, the Po of WT-CFTR in the presence of VX-770 already approaches ∼0.7, leaving little room for further enhancement. Second, for ATP-independent gating, the traces in Fig. 7 B clearly show a time-dependent decrease of the residual activity after ATP washout, likely reflecting dissociation of ATP from the catalysis-incompetent site (or site 1) of CFTR (see Lin et al., 2014, for details). This lack of a stationary recording for ATP-independent gating complicates quantitative analysis. However, because of the extremely low Po, the ΔNBD2- and G551D-CFTR constructs can serve as a convenient tool. In addition, by eliminating ATP hydrolysis from the equation, we can apply the principle of equilibrium thermodynamics to interpret gating modulation by VX-770 and NO3−. As ATP fails to increase the opening rate of these two mutant channels, the mathematical formula for Po can be simplified to τo/τc (or ko/kc), where τo and τc are mean open time and mean closed time, respectively, and ko and kc are opening rate and closing rate, respectively. Then the magnitude of increase in Po reflects corresponding changes in ko/kc, which, based on the transition-state theory of reaction rates, can be used to determine the free energy changes involved in gating modulation (see Materials and methods for details).

As seen in Fig. 8 A (inset), in an excised patch where the ΔNBD2-CFTR channels are activated by PKA and ATP in NO3− bath, changing the charge carrier to Cl− instantly decreases the current. In the same patch, VX-770, applied after the current is recovered by replacing bath Cl− to NO3−, further enhances the current. Subsequent substitution of bath NO3− with Cl− decreases the current amplitude to a level that is higher than the current in Cl− bath before the application of VX-770. This sort of experiment allows us to quantify the effects of VX-770, NO3−, and VX-770 plus NO3− in the same patch. A summary of the gating effects of NO3−, VX-770, and NO3− plus VX-770 is shown in Fig. 8 A. To our knowledge, these data represent the first time VX-770 is shown to increase the Po of ΔNBD2-CFTR, a result consistent with the proposition that VX-770 acts on CFTR’s TMDs (Jih and Hwang, 2013). Furthermore, the observation that VX-770 even works on a CFTR mutant with its gating machinery nearly demolished also explains why VX-770 is such a universal potentiator that can increases the activity of a wide spectrum CFTR mutants (Yu et al., 2012; Van Goor et al., 2014). Similar experimental protocols were executed for G551D-CFTR (Fig. 8 B). It is interesting to note that for both ΔNBD2- and G551D-CFTR, the fold increase of the Po by VX-770 is practically the same, regardless of whether the bath anion is Cl− or NO3−. Similarly, the fold increase of the Po by NO3− is virtually the same in the presence or absence of VX-770. In other words, the potentiation effect of neither NO3− nor VX-770 is dependent on the other reagent, resulting in a fold increase of the Po by a combination of VX-770 and NO3− close to the product of two individual effects (see Materials and methods for detailed mathematics). Mechanistic implications of these results will be discussed.

Although VX-770 and NO3− exhibit so many similarities in their effects on CFTR gating, the observation that additional effects by one reagent can be seen when CFTR is potentiated by the other one is more consistent with the idea that they act through different binding site(s). Indeed, it seems hard to imagine that these two chemically diverse molecules can bind to the same location in CFTR. One characteristic of hydrophobic VX-770 is that it is equally effective when applied from the intracellular side or from the extracellular side of the membrane (Jih and Hwang, 2013). In contrast, the experimental results shown in Fig. 9 indicate that the major gating effect of NO3− is seen when NO3− is applied from the cytoplasmic side of the channel. Here again, we took advantage of the technical ease of getting microscopic currents with the ΔR-CFTR construct. Fig. 9 A shows a recording of single-channel ΔR-CFTR current with NO3− in the pipette: the activity in Cl− bath is clearly lower than that in NO3− bath. Single-channel kinetic analysis (Fig. 9 B) further confirms that intracellular NO3− significantly increased the Po by 47 ± 6% (n = 15; P < 0.001). Of note, we cannot completely exclude the possibility that NO3− also modulates CFTR gating via a binding site on the extracellular side of the channel, as the Po is slightly but significantly higher (12 ± 5%; P < 0.05; compare Figs. 9 B and 5 B) when the pipette is filled with NO3−.

Figure 9.

Differential modulation of ΔR-CFTR gating by cytoplasmic and pipette NO3−. (A) Cytoplasmic NO3− boosts the Po of ΔR-CFTR when the pipette is filled with NO3−-containing solution. (B) Single-channel kinetic analysis reveals: First, external NO3− has slight effects on gating parameters (∼12% increase of the Po compared with Fig. 5 B). Second, in the presence of pipette NO3−, similar gating modulations as described in Fig. 5 B were observed when cytoplasmic Cl− was replaced with NO3−, indicating that the major binding site for the gating effect of NO3− is located on the cytoplasmic side of the membrane. Po, τo, and τc are as follows: 0.48 ± 0.02, 403 ± 49 ms, and 404 ± 57 ms for Cl−; and 0.71 ± 0.02, 776 ± 94 ms, and 281 ± 29 ms for NO3− (n = 15). The error bars represent the SEM of the mean.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrate that CFTR gating can be modulated by permeant ions such as bromide and nitrate. Single-channel kinetic analysis reveals that nitrate increases the Po of WT-CFTR by slightly increasing the opening rate but more dramatically prolonging the open time. Because nearly identical effects are observed with a CFTR construct whose R domain is completely deleted (ΔR-CFTR), we conclude that this effect of nitrate is primarily on gating steps and not a secondary effect on phosphorylation. This result also allows us to exclude the R domain as a potential molecular target for nitrate. Furthermore, the effects of nitrate are also present in channels that do not hydrolyze ATP or undergo NBD dimerization, a very surprising result, as these two molecular events play critical roles in controlling ATP-dependent gating of CFTR. Equally surprising is the observation that virtually all of the gating effects of VX-770, a hydrophobic CFTR potentiator, can be replicated—despite to a less extent—with nitrate, a negatively charged ion. In the discussion below, we will first describe the evolution of our understanding of CFTR gating mechanisms, speculate on the possible location(s) of nitrate’s action, and propose a physical picture to explain how nitrate and VX-770 modulate CFTR gating via an energetically additive mechanism.

How ATP controls CFTR gating has been an outstanding biophysical question of interest not only because of the fact that many disease-associated mutations cause gating defects (Wang et al., 2014) but also for the possible insight we may gain into the evolutionary relationship between ion channels and active transporters (Chen and Hwang, 2008). Perhaps one of the most compelling pieces of evidence attesting to this evolutionary relationship is the observation that ATP hydrolysis is intimately involved in controlling gate closure (Gadsby et al., 2006; Hwang and Sheppard, 2009; Jih and Hwang, 2012), and that the single-channel kinetics violates microscopic reversibility because of an input of the free energy from ATP hydrolysis (Gunderson and Kopito, 1995; Csanády et al., 2010; Jih et al., 2012a). This coupling between ATP hydrolysis and gating transitions has long been thought to be strict, i.e., a one-to-one stoichiometry between each ATP hydrolysis cycle and the gating cycle (Gunderson and Kopito, 1995; Vergani et al., 2005; Csanády et al., 2010; Tsai et al., 2010). Lately, by studying single-channel gating events of a CFTR mutant, R352C/Q, which exhibits unequivocal hydrolysis-dependent transitions of two distinct open states, Jih et al. (2012a) proposed an energetic coupling model featuring a more relaxed relationship between ATP hydrolysis in NBDs and opening/closing of the gate in CFTR’s TMDs. Although one cannot exclude the possibility that the new coupling mechanism has a more limited applicability, this gating model explicitly incorporates gating transitions occurring in the absence of ATP into the overall gating scheme, hence allowing interpretations of kinetic data obtained from studies on CFTR mutants with defective ATP-dependent gating such as G551D- and ΔNBD2-CFTR (Jih and Hwang, 2012; Lin et al., 2014). Moreover, by offering an ATP-dependent pathway linking the open state with a vacated site 2, the catalysis-competent site formed by the head of NBD2 and the tail of NBD1, to an open state with dimerized NBDs, the model also presents a unique mechanism for prolonging the open time of CFTR in addition to the well-established inhibition of ATP hydrolysis. This model was lately used successfully to interpret gating effects of VX-770 (Jih and Hwang, 2013), a CFTR potentiator best known for its clinical application for the treatment of patients with cystic fibrosis (Boyle and De Boeck, 2013).

During our studies, we were surprised that the effects of nitrate on CFTR gating turned out to be so similar to those of VX-770. These similarities include not only single-channel kinetics of ATP-dependent gating for WT-CFTR but also macroscopic relaxation time constant for channels locked in an open state by PPi (Fig. 4; cf. Jih and Hwang, 2013; Kopeikin et al., 2014). Perhaps most interestingly, in mutant channels with defective NBDs (i.e., G551D- and ΔNBD2-CFTR), nitrate and VX-770 seem to only differ quantitatively, but not qualitatively (Fig. 8). These results thus lead us to the conclusion that gating modulation by these two reagents does not require intact, functional NBDs. The observation that deletion of the R domain does not affect nitrate’s effects also eliminates the possibility of the R domain being the molecular target for nitrate.

Despite these similar gating effects of nitrate and VX-770, the fact that nitrate further increases the Po of WT-CFTR that has been maximally potentiated by VX-770 points to different sites of action. Indeed, previous studies suggest that the binding site for hydrophobic VX-770 is likely located at the interface between CFTR’s TMDs and the lipid core of the membrane bilayer. In contrast, the preferred action of cytoplasmic nitrate over pipette nitrate (Fig. 9) implicates a binding site for nitrate that is exposed to the cytoplasmic aqueous environment. Although we cannot exclude the possibility that this nitrate-binding site is located outside of CFTR’s permeation pathway, it is perhaps reasonable to at least consider the hypothesis that nitrate may modulate CFTR gating through binding in the pore.

It has been known since the 1970s that permeant ions can modulate the drug-induced “inactivation” kinetics of K+ channel in squid axons (Armstrong, 1974; cf. Demo and Yellen, 1991). Gating/permeation coupling in CLC-0 chloride channels was well established more than a decade ago (Richard and Miller, 1990; Chen and Miller, 1996). A recent report also documented effects of permeant ions on the gating of TMEM16B, a Ca2+-activated chloride channel (Betto et al., 2014). CFTR is no exception; there is some evidence for the effect of permeant ions on gating. For example, Wright et al. (2004) showed that lowering extracellular [Cl−] markedly decreases the Po of WT-CFTR. As far as we know, however, the current work represents the first systematic study of gating modulation of CFTR by a permeant ion. Although the proposition that nitrate modifies CFTR gating by binding in the pore awaits more studies to substantiate, this hypothesis is consistent with our previous reports on the possible gating motions in CFTR’s TMDs, including the pore-lining residues (Bai et al., 2010, 2011; Gao et al., 2013). Specifically, these cysteine-scanning studies suggest a large-scale conformational change in CFTR’s TMDs during opening and closing transitions. Some transmembrane segments may undergo rotational as well as translational movements that may markedly alter the pore architecture (e.g., Bai et al., 2010, 2011). In addition, significant rearrangements of CFTR’s TMDs may be part of the gating conformational changes (Gao et al., 2013). It is thus conceivable to envisage a perturbation of the free energy level of the open or closed configurations in TMDs by changing the ionic species in the pore formed by some of the transmembrane segments in CFTR. Indeed, a recent paper provides evidence for a gating effect by a negatively charged CFTR blocker (Linsdell, 2014; but cf. Ai et al., 2004; Csanády and Töröcsik, 2014).

Even though, as described above, whether nitrate works through binding in the CFTR pore is unknown, we can still contemplate a few potential approaches for tackling this issue in the offing. For example, if the acting site of nitrate is indeed in the pore, we anticipate that mutations of the pore-lining residues may alter its gating effects. However, it may be quite challenging to find the right residue to work with, as our recent cysteine-scanning studies have identified at least 18 positions that line the internal vestibule of CFTR (Bai et al., 2010, 2011; Gao et al., 2013). Another possible way to investigate the interaction between nitrate and the pore is to adopt a fairly useful strategy used in previous permeation studies of CFTR. By using a mixture of chloride and thiocyanate, Tabcharani et al. (1993) demonstrated the anomalous mole fraction effect, indicative of multi-ion occupancy in CFTR’s pore. As thiocyanate significantly decreases the single-channel conductance, and there is no evidence that this anion affects CFTR gating, it may not be suitable for gating studies. On the other hand, once nitrate is shown to exhibit a similar anomalous mole fraction effect on anion conductance of CFTR, we may examine if its gating effect is altered by different mixings of chloride and nitrate.

Regardless of whether we accept the idea that gating effects of nitrate are mediated through its binding in the pore, we can still conclude that nitrate, unlike VX-770, should exert its effect at the interface between the CFTR protein and the aqueous phase. In Fig. 10, we provide a putative physical picture to explain data presented in Fig. 8. In this schematic cartoon, CFTR gating is simplified—and actually oversimplified—into a two-state transition in equilibrium as what may happen for a gating mechanism without an active involvement of NBDs (e.g., ΔNBD2-CFTR). By acting on two distinct interfaces, VX-770 and nitrate can affect the free energy levels of both the open and closed states independently. Thus, the overall free energy changes between these two states with VX-770 plus nitrate could well be the sum of each free energy perturbation by individual reagent (see Materials and methods for details).

Because defective gating constitutes one of the major molecular mechanisms for cystic fibrosis (Wang et al., 2014), finding effective CFTR potentiators has been an outstanding goal in the field. To this end, great strides have been made in the past few years. The remarkable success in the clinical application of VX-770 for cystic fibrosis patients carrying the G551D mutation not only has benefited a subset of the overall patient population, but the fact that VX-770 rectifies the gating defect seen in the most common disease-associated mutation ΔF508 (Kopeikin et al., 2014) also sets the stage for its role in the therapeutics of a majority of cystic fibrosis patients. The current study, although it may be of limited clinical value, at least indicates multiple mechanisms (binding sites) for improving CFTR function. Recently, Csanády and Töröcsik (2014) reported a novel mechanism for the gating effects of CFTR potentiator NPPB, which appears to be distinct from the one presented here for VX-770 and nitrate. It surely will be interesting to understand mechanistic differences in the action of various CFTR potentiators, with the hope of finding pharmacological synergism that may prove valuable in attaining the ultimate goal of curing cystic fibrosis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Cindy Chu and Shenghui Hu for their technical assistance and Dr. Robert Bridges for providing VX-770. We also thank Dr. Kang-Yang Jih for his helpful discussion.

H.-I. Yeh and J.-T. Yeh are sponsored by Taipei Veterans General Hospital-National Yang-Ming University Excellent Physician Scientists Cultivation Program in Taiwan. This work is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01DK55835) and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (Hwang13P0 to T.-C. Hwang).

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Merritt C. Maduke served as editor.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper:

- ABC

- ATP-binding cassette

- NBD

- nucleotide-binding domain

- Po

- open probability

- PPi

- pyrophosphate

- TMD

- transmembrane domain

References

- Ai T., Bompadre S.G., Sohma Y., Wang X., Li M., and Hwang T.-C.. 2004. Direct effects of 9-anthracene compounds on cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gating. Pflugers Arch. 449:88–95 10.1007/s00424-004-1317-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong C.M.1974. Ionic pores, gates, and gating currents. Q. Rev. Biophys. 7:179–210 10.1017/S0033583500001402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y., Li M., and Hwang T.-C.. 2010. Dual roles of the sixth transmembrane segment of the CFTR chloride channel in gating and permeation. J. Gen. Physiol. 136:293–309 10.1085/jgp.201010480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y., Li M., and Hwang T.-C.. 2011. Structural basis for the channel function of a degraded ABC transporter, CFTR (ABCC7). J. Gen. Physiol. 138:495–507 10.1085/jgp.201110705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baukrowitz T., Hwang T.C., Nairn A.C., and Gadsby D.C.. 1994. Coupling of CFTR Cl- channel gating to an ATP hydrolysis cycle. Neuron. 12:473–482 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90206-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betto G., Cherian O.L., Pifferi S., Cenedese V., Boccaccio A., and Menini A.. 2014. Interactions between permeation and gating in the TMEM16B/anoctamin2 calcium-activated chloride channel. J. Gen. Physiol. 143:703–718 10.1085/jgp.201411182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bompadre S.G., Ai T., Cho J.H., Wang X., Sohma Y., Li M., and Hwang T.C.. 2005. CFTR gating I: Characterization of the ATP-dependent gating of a phosphorylation-independent CFTR channel (ΔR-CFTR). J. Gen. Physiol. 125:361–375 10.1085/jgp.200409227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle M.P., and De Boeck K.. 2013. A new era in the treatment of cystic fibrosis: correction of the underlying CFTR defect. Lancet Respir Med. 1:158–163 10.1016/S2213-2600(12)70057-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T.-Y.2003. Coupling gating with ion permeation in ClC channels. Sci. STKE. 2003:pe23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T.-Y., and Hwang T.-C.. 2008. CLC-0 and CFTR: Chloride channels evolved from transporters. Physiol. Rev. 88:351–387 10.1152/physrev.00058.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T.Y., and Miller C.. 1996. Nonequilibrium gating and voltage dependence of the ClC-0 Cl− channel. J. Gen. Physiol. 108:237–250 10.1085/jgp.108.4.237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras J.E., Srikumar D., and Holmgren M.. 2008. Gating at the selectivity filter in cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 105:3310–3314 10.1073/pnas.0709809105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotten J.F., and Welsh M.J.. 1997. Covalent modification of the regulatory domain irreversibly stimulates cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. J. Biol. Chem. 272:25617–25622 10.1074/jbc.272.41.25617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csanády L.2000. Rapid kinetic analysis of multichannel records by a simultaneous fit to all dwell-time histograms. Biophys. J. 78:785–799 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76636-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csanády L., and Töröcsik B.. 2014. Catalyst-like modulation of transition states for CFTR channel opening and closing: New stimulation strategy exploits nonequilibrium gating. J. Gen. Physiol. 143:269–287 10.1085/jgp.201311089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csanády L., Chan K.W., Seto-Young D., Kopsco D.C., Nairn A.C., and Gadsby D.C.. 2000. Severed channels probe regulation of gating of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator by its cytoplasmic domains. J. Gen. Physiol. 116:477–500 10.1085/jgp.116.3.477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csanády L., Vergani P., and Gadsby D.C.. 2010. Strict coupling between CFTR’s catalytic cycle and gating of its Cl− ion pore revealed by distributions of open channel burst durations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 107:1241–1246 10.1073/pnas.0911061107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui L., Aleksandrov L., Chang X.B., Hou Y.X., He L., Hegedus T., Gentzsch M., Aleksandrov A., Balch W.E., and Riordan J.R.. 2007. Domain interdependence in the biosynthetic assembly of CFTR. J. Mol. Biol. 365:981–994 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.10.086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson D.C., Smith S.S., and Mansoura M.K.. 1999. CFTR: Mechanism of anion conduction. Physiol. Rev. 79:S47–S75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demo S.D., and Yellen G.. 1991. The inactivation gate of the Shaker K+ channel behaves like an open-channel blocker. Neuron. 7:743–753 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90277-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutzler R., Campbell E.B., and MacKinnon R.. 2003. Gating the selectivity filter in ClC chloride channels. Science. 300:108–112 10.1126/science.1082708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckford P.D.W., Li C., Ramjeesingh M., and Bear C.E.. 2012. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) potentiator VX-770 (ivacaftor) opens the defective channel gate of mutant CFTR in a phosphorylation-dependent but ATP-independent manner. J. Biol. Chem. 287:36639–36649 10.1074/jbc.M112.393637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng L., Campbell E.B., Hsiung Y., and MacKinnon R.. 2010. Structure of a eukaryotic CLC transporter defines an intermediate state in the transport cycle. Science. 330:635–641 10.1126/science.1195230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng L., Campbell E.B., and MacKinnon R.. 2012. Molecular mechanism of proton transport in CLC Cl−/H+ exchange transporters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 109:11699–11704 10.1073/pnas.1205764109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadsby D.C., Vergani P., and Csanády L.. 2006. The ABC protein turned chloride channel whose failure causes cystic fibrosis. Nature. 440:477–483 10.1038/nature04712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X., Bai Y., and Hwang T.-C.. 2013. Cysteine scanning of CFTR’s first transmembrane segment reveals its plausible roles in gating and permeation. Biophys. J. 104:786–797 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.12.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson K.L., and Kopito R.R.. 1994. Effects of pyrophosphate and nucleotide analogs suggest a role for ATP hydrolysis in cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator channel gating. J. Biol. Chem. 269:19349–19353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson K.L., and Kopito R.R.. 1995. Conformational states of CFTR associated with channel gating: The role of ATP binding and hydrolysis. Cell. 82:231–239 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90310-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B.2001. Ionic Channels in Excitable membranes. Third edition Sinauer Associates, Inc, Sunderland, MA: 814 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang T.C., and Sheppard D.N.. 1999. Molecular pharmacology of the CFTR Cl− channel. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 20:448–453 10.1016/S0165-6147(99)01386-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang T.-C., and Sheppard D.N.. 2009. Gating of the CFTR Cl− channel by ATP-driven nucleotide-binding domain dimerisation. J. Physiol. 587:2151–2161 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.171595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang T.C., Nagel G., Nairn A.C., and Gadsby D.C.. 1994. Regulation of the gating of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator C1 channels by phosphorylation and ATP hydrolysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 91:4698–4702 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jih K.-Y., and Hwang T.-C.. 2012. Nonequilibrium gating of CFTR on an equilibrium theme. Physiology (Bethesda). 27:351–361 10.1152/physiol.00026.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jih K.-Y., and Hwang T.-C.. 2013. Vx-770 potentiates CFTR function by promoting decoupling between the gating cycle and ATP hydrolysis cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 110:4404–4409 10.1073/pnas.1215982110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jih K.-Y., Sohma Y., and Hwang T.-C.. 2012a. Nonintegral stoichiometry in CFTR gating revealed by a pore-lining mutation. J. Gen. Physiol. 140:347–359 10.1085/jgp.201210834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jih K.-Y., Sohma Y., Li M., and Hwang T.-C.. 2012b. Identification of a novel post-hydrolytic state in CFTR gating. J. Gen. Physiol. 139:359–370 10.1085/jgp.201210789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopeikin Z., Yuksek Z., Yang H.-Y., and Bompadre S.G.. 2014. Combined effects of VX-770 and VX-809 on several functional abnormalities of F508del-CFTR channels. J. Cyst. Fibros. 13:508–514 10.1016/j.jcf.2014.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin W.-Y., Jih K.-Y., and Hwang T.-C.. 2014. A single amino acid substitution in CFTR converts ATP to an inhibitory ligand. J. Gen. Physiol. 144:311–320 10.1085/jgp.201411247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linsdell P.2001. Relationship between anion binding and anion permeability revealed by mutagenesis within the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator chloride channel pore. J. Physiol. 531:51–66 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0051j.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linsdell P.2014. State-dependent blocker interactions with the CFTR chloride channel: implications for gating the pore. Pflugers Arch. 466:2243–2255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linsdell P., and Hanrahan J.W.. 1998. Adenosine triphosphate–dependent asymmetry of anion permeation in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator chloride channel. J. Gen. Physiol. 111:601–614 10.1085/jgp.111.4.601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linsdell P., Evagelidis A., and Hanrahan J.W.. 2000. Molecular determinants of anion selectivity in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator chloride channel pore. Biophys. J. 78:2973–2982 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76836-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., and Siegelbaum S.A.. 2000. Change of pore helix conformational state upon opening of cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. Neuron. 28:899–909 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)00162-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Holmgren M., Jurman M.E., and Yellen G.. 1997. Gated access to the pore of a voltage-dependent K+ channel. Neuron. 19:175–184 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80357-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees D.C., Johnson E., and Lewinson O.. 2009. ABC transporters: the power to change. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10:218–227 10.1038/nrm2646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard E.A., and Miller C.. 1990. Steady-state coupling of ion-channel conformations to a transmembrane ion gradient. Science. 247:1208–1210 10.1126/science.2156338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riordan J.R., Rommens J.M., Kerem B., Alon N., Rozmahel R., Grzelczak Z., Zielenski J., Lok S., Plavsic N., Chou J.L., et al. . 1989. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: cloning and characterization of complementary DNA. Science. 245:1066–1073 10.1126/science.2475911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard D.N., and Welsh M.J.. 1999. Structure and function of the CFTR chloride channel. Physiol. Rev. 79:S23–S45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S.S., Steinle E.D., Meyerhoff M.E., and Dawson D.C.. 1999. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Physical basis for lyotropic anion selectivity patterns. J. Gen. Physiol. 114:799–818 10.1085/jgp.114.6.799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szollosi A., Muallem D.R., Csanády L., and Vergani P.. 2011. Mutant cycles at CFTR’s non-canonical ATP-binding site support little interface separation during gating. J. Gen. Physiol. 137:549–562 10.1085/jgp.201110608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabcharani J.A., Rommens J.M., Hou Y.X., Chang X.B., Tsui L.C., Riordan J.R., and Hanrahan J.W.. 1993. Multi-ion pore behaviour in the CFTR chloride channel. Nature. 366:79–82 10.1038/366079a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai M.-F., Shimizu H., Sohma Y., Li M., and Hwang T.-C.. 2009. State-dependent modulation of CFTR gating by pyrophosphate. J. Gen. Physiol. 133:405–419 10.1085/jgp.200810186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai M.-F., Li M., and Hwang T.-C.. 2010. Stable ATP binding mediated by a partial NBD dimer of the CFTR chloride channel. J. Gen. Physiol. 135:399–414 10.1085/jgp.201010399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Goor F., Hadida S., Grootenhuis P.D.J., Burton B., Cao D., Neuberger T., Turnbull A., Singh A., Joubran J., Hazlewood A., et al. . 2009. Rescue of CF airway epithelial cell function in vitro by a CFTR potentiator, VX-770. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 106:18825–18830 10.1073/pnas.0904709106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Goor F., Yu H., Burton B., and Hoffman B.J.. 2014. Effect of ivacaftor on CFTR forms with missense mutations associated with defects in protein processing or function. J. Cyst. Fibros. 13:29–36 10.1016/j.jcf.2013.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergani P., Basso C., Mense M., Nairn A.C., and Gadsby D.C.. 2005. Control of the CFTR channel’s gates. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 33:1003–1007 10.1042/BST20051003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Wrennall J.A., Cai Z., Li H., and Sheppard D.N.. 2014. Understanding how cystic fibrosis mutations disrupt CFTR function: From single molecules to animal models. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 52:47–57 10.1016/j.biocel.2014.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright A.M., Gong X., Verdon B., Linsdell P., Mehta A., Riordan J.R., Argent B.E., and Gray M.A.. 2004. Novel regulation of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) channel gating by external chloride. J. Biol. Chem. 279:41658–41663 10.1074/jbc.M405517200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H., Burton B., Huang C.-J., Worley J., Cao D., Johnson J.P. Jr, Urrutia A., Joubran J., Seepersaud S., Sussky K., et al. . 2012. Ivacaftor potentiation of multiple CFTR channels with gating mutations. J. Cyst. Fibros. 11:237–245 10.1016/j.jcf.2011.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeltwanger S., Wang F., Wang G.T., Gillis K.D., and Hwang T.C.. 1999. Gating of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator chloride channels by adenosine triphosphate hydrolysis. Quantitative analysis of a cyclic gating scheme. J. Gen. Physiol. 113:541–554 10.1085/jgp.113.4.541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]