Abstract

Background

Rectal cancer patients’ expectations of health and function may affect their disease- and treatment-related experience, but how patients form expectations of post-surgery function has received little study.

Objective

We used a qualitative approach to explore patients’ expectations of outcomes related to bowel function following sphincter-preserving surgery (SPS) for rectal cancer.

Design and Setting

Individual telephone interviews with patients who were about to undergo SPS for rectal cancer.

Patients

26 patients (14 men, 12 women) with clinical stage (cTNM) I to III disease.

Main Outcome Measures

The semi-structured interview script contained open-ended questions on patients’ expectations of post-operative bowel function and its perceived impact on daily function and life. Two researchers analyzed the interview transcripts for emergent themes using a grounded theory approach.

Results

Participants’ expectations of bowel function reflected three major themes: (1) information sources, (2) personal attitudes, and (3) expected outcomes. The expected outcomes theme contained references to specific symptoms and participants’ descriptions of the certainty, importance and imminence of expected outcomes. Despite multiple information sources and attempts at maintaining a positive personal attitude, participants expressed much uncertainty about their long term bowel function. They were more focused on what they considered more important and imminent concerns about being cancer-free and getting through surgery.

Limitations

This study is limited by context in terms of the timing of interviews (relative to the treatment course). The transferability to other contexts requires further study.

Conclusions

Patients’ expectations of long term functional outcomes cannot be considered outside of the overall context of the cancer-experience and the relative importance and imminence of cancer- and treatment-related events. Recognizing the complexities of the expectation formation process offers opportunities to develop strategies to enhance patient education and appropriately manage expectations, attend to immediate and long term concerns, and support patients through the treatment and recovery process.

Keywords: Rectal cancer, surgery, expectations, bowel function, quality of life, qualitative research

The indications and rates of sphincter-preserving surgery (SPS) for patients with rectal cancer have increased in recent years, which has allowed in increasing number of patients to avoid permanent stomas.1–2 However, despite the trend towards more SPS, multiple studies suggest that patients’ functional outcomes after SPS are suboptimal.3–7 Patients commonly experience significant bowel symptoms such as incomplete evacuation, clustering, frequency, unformed stool, and gas incontinence after SPS for rectal cancer.3 Overall, 43% of patients report dissatisfaction with their bowel function after SPS.3

Whether patients expect to experience these changes in bowel function is open to question. In a recent abstract, we reported that patients about to undergo SPS for rectal cancer did not expect their post-operative bowel function to significantly differ from their pre-operative function.8 The reasons for the apparent discordance between patients’ expectations and reported post-operative function are unclear but may have important clinical implications. Clinicians need to understand patients’ expectations as part of the healthcare interaction. Expectations of outcomes affect how patients perceive and select between treatment options, inform the consent process, and may also influence their satisfaction and post-operative quality of life.9–11

Complex psychosocial processes, which include the processes involved in the development of expectations, are difficult to study through purely quantitative methodologies. In contrast, qualitative methodologies using open-ended techniques may be more effective in eliciting the perspectives and meanings that underlie these processes.12–14 For example, in a previous study involving rectal cancer patients with temporary stomas, we reported on some of the limitations of standard quantitative Quality of Life (QOL) instruments in measuring the effects of stoma-related problems.15 However, by adding a qualitative component to the study, we were able to identity a “response shift” among patients, which complemented the quantitative data and helped to explain the quantitative QOL findings.15 In the present study, we used a qualitative methodology to explore patients’ expectations of outcomes related to bowel function after SPS for rectal cancer. An inductive framework generated from an exploration at this level can inform future research to enhance patient education prior to surgery.

Methods

Participants and Sampling

The Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) Institutional Review Board approved this study. We invited English-speaking patients with clinical stage (cTNM) I to III rectal cancer planning to undergo restorative proctectomy (with or without temporary stoma) to participate in this study. We included only patients undergoing surgery with curative intent. Patients in whom bowel continuity was unlikely to be preserved (i.e., those deemed by the primary surgeon to require an APR or Hartmann procedure with permanent end colostomy) were excluded from participation.

We contacted a convenience sample of 37 eligible patients between July 2008 and June 2009 to participate in our study. Twenty six of these patients agreed to participate (Table 1). After analyzing the 26th interview, we found that themes were saturated in the data at which point we stopped sampling, consistent with a theoretical sampling strategy.16 Eleven patients declined our invitation to participate and their characteristics were not different from those who participated (data not shown).

Table 1.

Participant, treatment, and tumor characteristics

| Characteristic | N | Value (%) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Age, years (mean ± standard deviation) | 56.0 ± 13.6 | |

|

| ||

| Sex | ||

| Female | 12 | 46.2% |

| Male | 14 | 53.8% |

|

| ||

| Employment Status | ||

| Employed | 18 | 69.2% |

| Unemployed | 4 | 15.4% |

| Retired | 4 | 15.4% |

|

| ||

| Marital Status | ||

| Married | 14 | 53.8% |

| Single | 8 | 30.8% |

| Widowed | 4 | 15.4% |

|

| ||

| Neoadjuvant treatments | ||

| Radiation and chemotherapy | 12 | 46.2% |

| Radiation alone | 1 | 3.8% |

| Chemotherapy alone | 7 | 26.9% |

| None | 6 | 23.1% |

|

| ||

| Procedure performed | ||

| LAR | 12 | 46.2% |

| LAR and proximal diverting stoma | 2 | 7.7% |

| LAR with CAA and proximal diverting stoma | 12 | 46.2% |

|

| ||

| Final pathological TNM stage* | ||

| Stage 0 | 6 | 23.1% |

| Stage I | 7 | 26.9% |

| Stage II | 6 | 23.1% |

| Stage III | 7 | 26.9% |

LAR low anterior resection, CAA coloanal anastomosis, TNM stage American Joint Commission on Cancer TNM stage.

Includes cases treated with neoadjuvant treatment before surgery (ypTNM stage) if applicable.

Data Collection

The primary investigator (J.P.) or research assistant (L.P.) conducted telephone interviews with individual participants using a semi-structured interview script. Data collected in telephone interviews are comparable to face-to-face interviews, but telephone interviews offer more convenience for patients.17–18 This interviewing method is particularly useful when collecting data from geographically dispersed populations, such as those presenting to our institution.

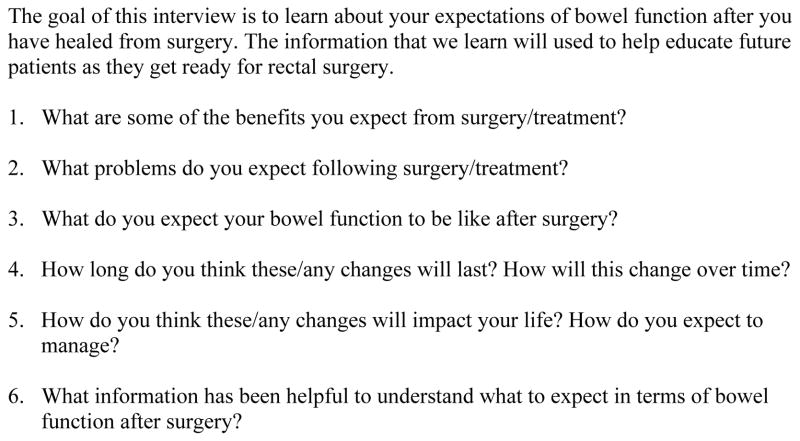

The interview script contained open-ended questions on the benefits and risks of surgical treatment, expectations of post-operative bowel function, and the perceived impact of bowel function on patients’ daily function and life (Figure 1). The interviews took place after the completion of neoadjuvant treatments (if applicable) and after patients signed informed consent for resection of their cancer but before the day of their surgery. Each interview lasted approximately twenty minutes. The interviews were audio recorded and then transcribed verbatim by a research assistant. We removed identifying features (name and medical record number) from the transcripts, but we included participants’ age, gender, and employment status on transcripts to facilitate identifying trends in the data.

Figure 1.

Semi-structured interview script

Data Analysis

We analyzed the data for emergent themes and developed a thematic coding structure using a grounded theory approach.13, 16 This approach included an iterative study design that involved cycles of concurrent data collection and analysis with the results of the ongoing analysis informing successive data collection. Two researchers with backgrounds in surgery and education (J.P. and H.B.N.) independently read the interview transcripts. The themes and coding structures were compared between researchers and discrepancies resolved by consensus agreement. Constant comparative techniques were used as the analysis progressed to further revise and refine themes.

A single researcher (J.P.) applied the final confirmed coding structure to the entire data set. NVivo qualitative data analysis software (QSR International PTY Ltd., Melbourne, Australia) was used to organize the data.

Results

The interviews yielded 93 pages of transcribed text for analysis. We did not find any consistent differences in the major themes based on age or gender, and we therefore applied a single coding structure to the entire data set.

We identified three major themes that we termed: (1) information sources, (2) personal attitudes, and (3) expected outcomes. Each of these themes is described below.

Information Sources

Participants described five main sources from which they derived the knowledge or beliefs that shaped their expectations. These sources were: (1) their previous personal experiences (or lack thereof), (2) information from healthcare professionals, (3) paper-based educational resources, (4) online resources and (5) the experiences of others. Table 2 presents exemplar quotations for each of the Information Sources.

Table 2.

Sources from which participants derived the knowledge or beliefs that shaped their expectations with exemplar excerpt of each of these sources.

| Source | Exemplar excerpt |

|---|---|

| Personal experience |

|

| Information from healthcare professionals |

|

| Paper-based resources |

|

| On line resources |

|

| Experiences of others |

|

The lack of previous personal experience with cancer was a dominant theme. For the majority of the participants, the development of cancer and its subsequent treatment were completely new experiences. Consequently, many participants expressed a great deal of uncertainty about knowing what to expect after surgery. One participant articulated her uncertainty about her post-treatment bowel function as follows: “I have read the literature… but really I don’t know what to expect since I have never been through this before” (67 year old female patient).

Without prior personal experiences from which to draw, participants relied heavily on other sources for information to shape their expectations of bowel function. In particular, participants highlighted the importance of the information provided by their surgeon and other health care providers, including radiation and medical oncologists, and nurses, with whom they had contact. Participants viewed the information provided by their surgeon and health care providers as credible and useful. Discussions with health care providers had some advantages over other information sources because they allowed for interaction between patients and providers. One participant described the advantages of this interaction as follows: “(Discussions with my surgeon) have been particularly good because there is interaction, unlike reading a fact or two from a book or pamphlet. I can actually get clarification and fine tune what’s being exchanged” (59 year old male patient).

Participants described the written materials provided by the hospital as useful resources that helped to provide information on what to expect with and after surgery. Many participants also attempted to educate themselves by going online and exploring the internet for information. Some thought online sources were useful, while others questioned the credibility of information and thought it only led to more anxiety. Finally, some participants drew on the experiences of other cancer patients’ as a source of information. These included being introduced to other people with cancer by acquaintances or joining online discussion groups of others with cancer.

Personal Attitude

The personal attitude theme contained participants’ references to their attitudes and general tendencies expect positive or negative outcomes, consistent with the constructs of dispositional optimism and pessimism.19 Participants acknowledged the risks of surgery but for the most part they emphasized their attempts at maintaining a positive attitude and optimism as they approached surgery, as demonstrated by the following excerpt: “I don’t have any major negative expectations (of bowel function). If anything, they’re more positive. Hopefully I’m not being overly optimistic” (59-year old male patient). Some participants tried to maintain a positive attitude as a coping mechanism. As one participant candidly stated in discussing her expectations, “I’m thinking positively here. I have to… otherwise I would go crazy” (58-year old female patient).

Expected Outcomes

In discussing their expectations of bowel function after surgery, participants described specific symptoms and three major, inter-related properties of their expectations, which we termed: (1) certainty, (2) importance and (3) imminence. Table 3 presents exemplar quotations of each of these properties.

Table 3.

Expectation properties with exemplar excerpts of each property. Refer to text for descriptions of each property.

| Property | Exemplar excerpt |

|---|---|

| Certainty |

|

| Importance |

|

| Imminence |

|

Participants described numerous anticipated symptoms and a range of expected outcomes related to bowel function. The main symptoms that they were concerned about were continence, diarrhea, frequency, and urgency. There were a range of expected post-surgery functional outcomes, from permanently poor function to temporary problems to completely normal bowel function. Many participants had problems with their pre-treatment bowel function, which they attributed to their rectal cancer, and some expected improved function after surgery.

The certainty property referred to the confidence with which participants held an expectation of an outcome. Despite articulating a range of symptoms related to bowel function, participants held their expectations with varying degrees of certainty, with most expressing a great deal of uncertainty in knowing exactly what to expect. One participant expressed his uncertainty as follows: “I’ve been told (my bowel function) will not be quite as robust as it was, but I do wonder about it. I guess I won’t really know for sure until I start to experience it” (59 year old male patient). With uncertainty, many patients developed a wait-and-see approach, as demonstrated by the following excerpt: “I’m really not sure what to expect… I don’t think I will know until I get there” (58 year old male patient).

The importance property refers to the significance that individual participants place on a specific outcome. While participants expressed concern about their bowel function after treatment when explicitly asked, it was not necessarily the most important outcome to them. Participants placed utmost importance on being cancer-free, and then on getting though surgery, and for many, dealing with a temporary stoma.

The imminence property contained references to how close in time a given outcome was for patients. Some participants had put little thought into their post-treatment bowel function because they did not see it as an imminent event. They expressed more concern with the outcomes of their upcoming operation, immediate recovery and the potential early complications from surgery. The return of bowel function would be even further delayed for the many participants who were told by their surgeons that they would likely have a temporary stoma after surgery. The imminence of these events and concern around them prevented some participants from forming expectations related to other outcomes. One participant expressed their thought process as follows: “I haven’t really thought about my bowel function. I try not to. I am so nervous about the surgery so I haven’t really thought about that” (51 year old female patient).

Discussion

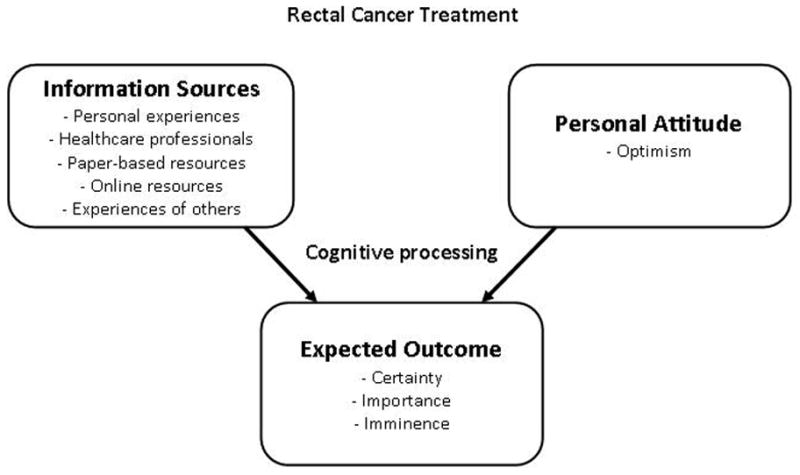

The present paper does not attempt to define specific expectations of functional outcomes but rather tries to understand how they are formed in the context of patients dealing with cancer and major surgery. Our findings suggest the information that patients’ receive and carry, and their personal attitudes play large roles in their expectations of post-treatment function. We further found that patient’s expectations of outcomes could vary along several parameters or properties, including the certainty of the expectation, its perceived importance, and how imminently it required attention. Figure 2 shows a conceptual model of the proposed interaction of these themes.

Figure 2.

Conceptual model of the proposed interaction of major themes in the expectation formation process. Rectal cancer treatment is shown as the precipitating factor.

Our conceptual model shares elements common to models of expectancy processes proposed by other authors, but we found that our themes in the context of major cancer surgery mapped only partly to these other models. Previous models by Janzen et al.20 and Olson et al.21 presented direct personal experience and indirect experience as antecedents to an expectancy, which parallel our information sources. However, neither of these models account for an individual’s attitude in the expectancy process, although its role has been effectively described in more recent literature.22

Of the information sources, direct personal experience is perhaps the most important factor in the formation of expectations.20–21 Expectations derived from beliefs based on personal experience may be held more strongly and more confidently than beliefs not based on direct experience.21 For our study participants, however, dealing with rectal cancer was an entirely new experience and they described few if any comparable personal experiences. The lack of direct experience was associated with much uncertainty about surgery and post-surgery function despite the other information sources.

Even though they experienced uncertainty, most of our study participants expressed a positive attitude when directly asked about their future function. Our findings are consistent with the psychology literature, which has consistently shown that people are on average optimistic about their personal future.23 Such optimism has been documented against several benchmarks, including comparisons to an individual’s current circumstances and to similar others. Roese et al. explain this finding by suggesting that people are motivated to be optimistic because it produces a positive affect and makes them feel better.22 Other authors suggest optimism in moderation can facilitate psychological well being.

We routinely discuss the long term functional outcomes after SPS with patients prior to resection at our institution, but our study participants experienced uncertainty and had problems forming and articulating their expectations despite these discussions. Previous studies involving multiple surgical procedures have reported that patients have difficulty understanding and recalling information, particularly with respect to operative risks and outcomes.24–25 These studies further suggest that patients’ age, culture/first language, educational status were all factors associated with patients’ understanding of operative procedures and outcomes.26 Our findings add to this literature by showing that contextual factors, specifically the importance and imminence of other events, may also contribute to patients’ difficulties understanding outcomes and forming expectations. First, participants viewed their expectations of bowel function as important, but placed more importance on being cancer-free and getting through surgery. Second, for many participants, the return of bowel function lacked imminence. More pressing and perhaps more immediately anxiety-provoking were concerns about their upcoming surgery, early complications, recovery, and the possibility of having a stoma.

Even though patients may have more important or more imminent concerns, it seems misleading and potentially irresponsible to not fully disclose information on the potential risks and long-term sequela of treatment prior to their resection. Patients’ information needs may be different at different points in treatment, but they still need to have some understanding of these issues as part of the initial decision-making and informed consent process.

Our findings give us reason to pause and reflect on how clinicians approach interactions with patients prior to major cancer surgery. Key questions that arise are: when, how, and how much information to provide. Based on our findings, we suggest that potential strategies include: (1) discussions at multiple points in time, (2) the inclusion of family members in discussions, and (3) adjuncts to clinical consults. Patients’ priorities and how they receive information may change over time depending on where they are in the course of their treatments. Thus, discussions at multiple points in time (initial consultation, in hospital recovery period, pre-stoma reversal office visit) centered on long term outcomes may reinforce information. The inclusion of family members or delegates may further enhance understanding since they may have different priorities and may be able to better process information when patients are overwhelmed.27 Finally, adjuncts to clinical consults, such as pamphlets and high quality internet-based resources, can serve as additional references source that allow patients to review information when they are ready and at their own pace. Recent reviews suggest some measureable benefits with these adjuncts in a majority but not all studies.28–29 Clinical decision aids, which present treatment options and potential outcomes for each option, may also help improve understanding and facilitate decision making.30–31

This study is limited by context. First, we interviewed participants in the days to weeks after their office visit in which we discussed the benefits and risks of resection, including post-operative bowel function, and obtained informed consent, but before the day of surgery itself. For patients with temporary stomas, we routinely discuss long term bowel function again prior to their stoma reversal surgery and if we interviewed them at this point, perhaps our findings might be different. However, bowel dysfunction is associated with the primary resection and not the stoma reversal (although it does not manifest until after stoma closure). We therefore assert that patients should have some understanding of long term functional risks prior to the initial resection and not after the fact, and chose the time period for interviews accordingly. Second, our sample included self-selected patients presenting to a high volume cancer center, many of whom were very motivated to undergo SPS. The transferability of findings to other contexts requires further study. Third, we presented a conceptual model with the proposed interaction of the major themes, but we accept that the expectation formation process is more complex than presented in this model and further research is required to understand the precise mechanisms that occur, particularly during the cognitive processing phase.

Conclusions

Patients’ expectations of outcomes can affect their experience with disease and treatment, and understanding and managing these expectations is an integral part of the clinician-patient interaction. Participants in our study experienced uncertainty and difficulties forming expectations about long term bowel function because they lacked previous experience with rectal cancer and were more focused on what they perceived as relatively more important and imminent concerns about their underlying cancer and upcoming surgery. Thus, patients’ expectations of long term functional outcome cannot be considered outside of the overall context of the rectal cancer-experience and the relative importance and imminence of cancer- and treatment-related events. Recognizing the complexities of the expectation formation process offers opportunities to develop strategies to enhance patient education and appropriately manage expectations, attend to immediate and long term concerns, and support them through the cancer treatment process.

Acknowledgments

Funding:

Supported in part by an American Society for Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Career Development Award (Dr. Temple)

Footnotes

Relevant Conflicts of Interest: None

Contributions:

Conception and design, or data acquisition, or data analysis and interpretation: Park, Neumann, Bennett, Polskin, Phang, Wong, Temple

Drafting or critical revisions: Park, Neumann, Bennett, Polskin, Phang, Wong, Temple

Final approval: Park, Neumann, Bennett, Polskin, Phang, Temple

References

- 1.Ricciardi R, Virnig BA, Madoff RD, Rothenberger DA, Baxter NN. The status of radical proctectomy and sphincter-sparing surgery in the United States. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:1119–1127. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-0250-5. discussion 1126–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tilney HS, Heriot AG, Purkayastha S, et al. A national perspective on the decline of abdominoperineal resection for rectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2008;247:77–84. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31816076c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Temple LK, Bacik J, Savatta SG, et al. The development of a validated instrument to evaluate bowel function after sphincter-preserving surgery for rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1353–1365. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0942-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shibata D, Guillem JG, Lanouette N, et al. Functional and quality-of-life outcomes in patients with rectal cancer after combined modality therapy, intraoperative radiation therapy, and sphincter preservation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:752–758. doi: 10.1007/BF02238009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams N, Seow-Choen F. Physiological and functional outcome following ultra-low anterior resection with colon pouch-anal anastomosis. Br J Surg. 1998;85:1029–1035. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paty PB, Enker WE, Cohen AM, Minsky BD, Friedlander-Klar H. Long-term functional results of coloanal anastomosis for rectal cancer. Am J Surg. 1994;167:90–94. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(94)90058-2. discussion 94–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Emmertsen KJ, Laurberg S. Low anterior resection syndrome score: development and validation of a symptom-based scoring system for bowel dysfunction after low anterior resection for rectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2012;255:922–928. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31824f1c21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park J, Fuzesi SJ, Duhamel KN, et al. Do Patients Expect Changes in Functional Outcome Following Sphincter Preserving Surgery for Rectal Cancer? Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(S1):110. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carr AJ, Gibson B, Robinson PG. Measuring quality of life: Is quality of life determined by expectations or experience? BMJ. 2001;322:1240–1243. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7296.1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koller M, Lorenz W, Wagner K, et al. Expectations and quality of life of cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy. J R Soc Med. 2000;93:621–628. doi: 10.1177/014107680009301205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thompson AG, Sunol R. Expectations as determinants of patient satisfaction: concepts, theory and evidence. Int J Qual Health Care. 1995;7:127–141. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/7.2.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoshmand LT. Alternate research paradigms: a review and teaching proposal. Couns Psychol. 1989;17:3–79. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strauss AL, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park J, Woodrow SI, Reznick RK, Beales J, MacRae HM. Patient care is a collective responsibility: perceptions of professional responsibility in surgery. Surgery. 2007;142:111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neuman HB, Park J, Fuzesi S, Temple LK. Rectal cancer patients’ quality of life with a temporary stoma: shifting perspectives. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:1117–1124. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182686213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Creswell J. Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five traditions. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chapple A. Use of telephone interviewing for qualitative research. Nurs Res. 1999;6:85–93. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carr EC, Worth A. Use of the telephone interview for research. J Res Nurs. 2001;6:511–524. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carver CS, Scheier MF. Optimism. In: Leary MR, Hoyle RH, editors. Handbook of individual differences in social behavior. New York: Guilford; 2009. pp. 330–342. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Janzen JA, Silvius J, Jacobs S, Slaughter S, Dalziel W, Drummond N. What is a health expectation? Developing a pragmatic conceptual model from psychological theory. Health Expect. 2006;9:37–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2006.00363.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olson JM, Roese NJ, Zanna MP. Expectancies. In: Higgins ET, Kruglanski AW, editors. Social psychology: handbook of basic principles. New York: Guilford; 1996. pp. 211–238. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roese NJ, Sherman JW. Expectancy. In: Kruglanski AW, Higgins ET, editors. Social pyschology: handbook of basic principles. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. pp. 91–115. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Newby-Clark IR, Ross M. Conceiving the past and future. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2003;29:807–818. doi: 10.1177/0146167203029007001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stanley BM, Walters DJ, Maddern GJ. Informed consent: how much information is enough? Aust N Z J Surg. 1998;68:788–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1998.tb04678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scheer AS, O’Connor AM, Chan BP, et al. The myth of informed consent in rectal cancer surgery: what do patients retain? Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:970–975. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31825f2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fink AS, Prochazka AV, Henderson WG, et al. Predictors of comprehension during surgical informed consent. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210:919–926. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berman L, Curry L, Gusberg R, Dardik A, Fraenkel L. Informed consent for abdominal aortic aneurysm repair: The patient’s perspective. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48:296–302. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.03.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schenker Y, Fernandez A, Sudore R, Schillinger D. Interventions to improve patient comprehension in informed consent for medical and surgical procedures: a systematic review. Med Decis Making. 2011;31:151–173. doi: 10.1177/0272989X10364247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mulsow JJ, Feeley TM, Tierney S. Beyond consent--improving understanding in surgical patients. Am J Surg. 2012;203:112–120. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neuman HB, Charlson ME, Temple LK. Is there a role for decision aids in cancer-related decisions? Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2007;62:240–250. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Masya LM, Young JM, Solomon MJ, Harrison JD, Dennis RJ, Salkeld GP. Preferences for outcomes of treatment for rectal cancer: patient and clinician utilities and their application in an interactive computer-based decision aid. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:1994–2002. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181c001b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]