Abstract

Background

The factors determining sex are diverse in vertebrates and especially so in teleost fishes. Only a handful of master sex-determining genes have been identified, however great efforts have been undertaken to characterize the subsequent genetic network of sex differentiation in various organisms. East African cichlids offer an ideal model system to study the complexity of sexual development, since many different sex-determining mechanisms occur in closely related species of this fish family. Here, we investigated the sex-determining system and gene expression profiles during male development of Astatotilapia burtoni, a member of the rapidly radiating and exceptionally species-rich haplochromine lineage.

Results

Crossing experiments with hormonally sex-reversed fish provided evidence for an XX-XY sex determination system in A. burtoni. Resultant all-male broods were used to assess gene expression patterns throughout development of a set of candidate genes, previously characterized in adult cichlids only.

Conclusions

We could identify the onset of gonad sexual differentiation at 11–12 dpf. The expression profiles identified wnt4B and wt1A as the earliest gonad markers in A. burtoni. Furthermore we identified late testis genes (cyp19a1A, gsdf, dmrt1 and gata4), and brain markers (ctnnb1A, ctnnb1B, dax1A, foxl2, foxl3, nanos1A, nanos1B, rspo1, sf-1, sox9A and sox9B).

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12863-014-0140-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Sexual development, Cichlidae, Adaptive radiation, Speciation, Gene expression profiles

Background

Sexual development encompasses sex determination and sex differentiation and can be viewed as a complex genetic network that is initiated by a sex-determining trigger mediating the expression of sex differentiation genes, which ultimately establish the male or female phenotype [1]. In teleost fishes, with over 25,000 species the largest vertebrate group, sex determination mechanisms are much more variable compared to other vertebrates [2]. So far, six master sex-determining genes have been identified in teleosts, namely dmy/dmrt1bY in Oryzias latipes and O. curvinotus [3,4], gsdfY in O. luzonensis [5], sox3 in O. dancena [6], amhy in Odontesthes hatcheri [7], amhr2 in Takifugu rubripes [8] and sdY in Oncorhynchus mykiss and several other salmonids [9,10]. In addition to this variation in the initial regulators, we and others could show recently that also the subsequent genetic steps of sex differentiation are not conserved in fishes, asking for further investigation of the mechanisms of sexual development in this group of animals [11,12].

Master sex-determining genes are thought to be expressed early in development, thus marking the initial time point of the sexual development cascade. Their expression then either decreases directly after (comparable to the expression pattern shown in Figure 1A and in particular described for dmy/dmrt1bY in O. latipes [13]) or is maintained during the juvenile stage (as suggested for amhy [7] and sdY [9]). To the best of our knowledge, there is no example of a sex determination gene that is still highly expressed in adult fish. However, expression studies on several fish sex determination genes covering the development from embryo to adults are lacking, and in mammals, the sex-determining gene sry is expressed in adult testis of mouse and rat [14,15].

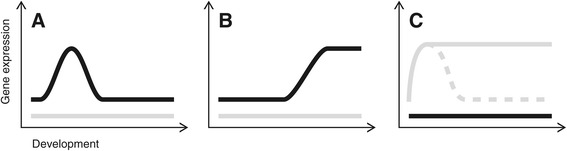

Figure 1.

Schematic expression patterns of sexual development genes. The graphs show possible expression profiles post fertilization in the developing brain (grey line) and testis (black line). (A) Early testis genes (including sex-determining genes) are highly expressed before and/or at the onset of gonadal formation and subsequently down regulated. (B) Late testis genes are expressed later in development, mainly during the formation and maintenance of gonads. (C) Brain genes are higher expressed in the brains than in the testis, forming the brain and/or influencing the sexual development gene network via the action of hormones. Their expression can be maintained (continuous line) or decreased (dashed line) after the first increase in expression.

Sex differentiation genes, on the other hand, can act at different time points after their initiation until sexual maturity (i.e., until gonads are fully developed) or even afterwards, e.g., by being involved in gonad maintenance and function (Figure 1B and exemplified by dmrt1 [16-18]).

Similarly to gene expression patterns in the gonads, sex differentiation genes can be expressed in the brain as part of the hypothalamus-pituitary-gonadal axis, and hence can -like gonad genes- follow one of the two patterns shown in Figure 1C.

In general, gonads are formed by the interplay of sexual development genes and the action of hormones [19-22]. This can be a rather plastic process, especially in fish, making it more difficult to classify sex differentiation genes according to their expression profiles and also questioning a separation between sex determination and differentiation [23].

Cichlid fishes, and the species flocks of cichlids in the East African Great lakes in particular, are an excellent model system in evolutionary biology, with hundreds of closely related species showing a high degree of diversity in morphology, behavior and ecology [24-27]. This diversity also seems to apply to sex determination systems, as evidenced by data suggesting that different mechanisms occur in cichlids including sex determination via environmental (temperature and pH) and genetic factors (single gene or polygenic actions), or a combination thereof [28-33]. The best-studied cichlid in terms of sexual development is the widely distributed and farmed Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus), which has an XX-XY sex-determining system that can strongly be influenced by temperature [34]. There are two time windows (2–3 days post fertilization, dpf, and 10–20 dpf), in which temperature and steroid hormones can override genetic sex determination in the Nile tilapia, with the actual critical time period of gonad differentiation at 9 to 15 dpf [34 and references therein]. Studies of sexual development in the Nile tilapia encompass both, genetic and morphological data, and therefore make this species a good reference system.

Here, we focused on another cichlid species, Astatotilapia burtoni, which inhabits Lake Tanganyika, and its affluent rivers, and is a model system especially in behavioral but also genetic research (e.g., [35]). This sexually dimorphic species, in which males are larger and brightly colored whereas females are rather dull, belongs to the most derived and species-rich lineage of East African cichlids, the haplochromines. Like the Nile tilapia, A. burtoni is a maternal mouthbrooder; the female incubates the fertilized eggs in her buccal cavity at least until hatching. Because of different developmental pace, the sexual development of A. burtoni cannot be compared in exact (day to day) time steps to the Nile tilapia. Although Nile tilapia and A. burtoni embryos hatch approximately at the same age (5–6 dpf [36] and 4–7 dpf, [37], respectively), Nile tilapia embryos start free swimming earlier than A. burtoni embryos (12 and 14 dpf, respectively [36,37]) but become sexually mature later (at the age of 22–24 weeks [38] compared to 13–14 weeks in the here used A. burtoni strain, personal observation). Until now, the embryonic and juvenile development of A. burtoni has not been studied in detail. Even though A. burtoni is one of the five cichlid species with a sequenced genome [39], neither the sex-determining system nor the time window of sex determination have been characterized.

Based on the assumption that sex is determined genetically, we used a common approach to infer male or female heterogamety. We generated mono-sex fish groups over steroid hormone treatments via food and conducted crossing experiments. The resultant sex ratios point to an XX-XY sex-determining system in A. burtoni. Subsequent crossings were carried out to generate a YY-supermale to sire male-only offspring. Making use of candidate genes expressed in brain and gonad tissue of adult A. burtoni [11], we studied changes in gene expression throughout male sexual development. Without prior knowledge on the time window of actual sex determination in this species, we decided to investigate gene expression as early as possible starting at 7 dpf. We profiled expression of sexual development genes from 7–48 dpf using high throughput quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction on single individuals. Most of the gene expression profiles corresponded to one of the following patterns: early testis genes, late testis genes and brain/head genes (Figure 1).

Results

Generating all-male broods in A. burtoni

Sexual development in fish is plastic and sex reversal can be induced in a variety of species even after reaching sexual maturity [40]. For these purposes, steroid hormones or hormone synthesis inhibitors can be administered over the surrounding water or via food supply. Here, we fed four A. burtoni broods with estrogen treated flake food during four weeks of development in order to obtain all-female broods. We started treatment at the earliest feeding point of this species, at around 14 dpf. This procedure has been carried out successfully in another cichlid species, the Nile tilapia (personal communication H D’Cotta), which starts feeding at around 12 dpf [36]. After treatment, we obtained 100% morphological females in all broods. These natural female and feminized fish were used for crossings with untreated, normal males. Among the offspring of these individual crossings, four broods showed a ~ 1 : 3 (female : male) sex ratio, whereas other crosses, likely derived from normal females, which can morphologically not be distinguished from sex-reversed individuals, had a sex ratio of approximately 1 : 1. This is a strong indication for an XY-XX system in A. burtoni (Figure 2). Note that a ZZ-ZW female heterogametic sex determination system can be ruled out for A. burtoni, because sex-reversed ZZ females would have produced only males in the first generation of crossings, all of our crosses however contained at least 1/3 female offspring.

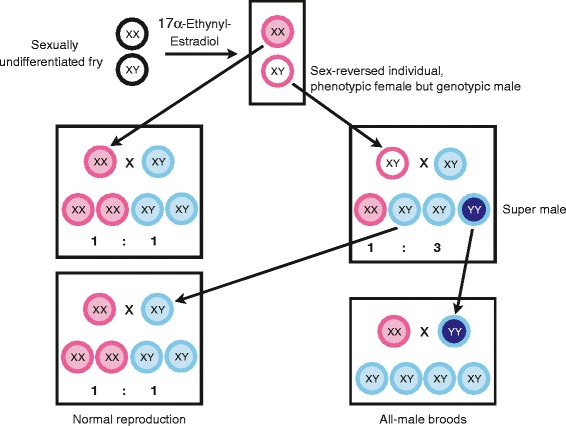

Figure 2.

Crossing scheme to obtain all-male broods from estrogen sex-reversed fish. Sexually undifferentiated fry including both, XX- and XY-genotypes, were treated with estrogen resulting in only phenotypical females. These females – genetic females and sex-reversed genotypic males – were then crossed to untreated genotypic males. Crossing of XX-females to untreated males (left site) reflect the normal reproduction with a sex ratio of 1:1, with the corresponding female XX and male XY genotypes in the offspring. Crossing of sex-reversed XY-females to untreated XY-males led to a sex ratio of 1:3 with the genotypes XX (phenotype female), XY (phenotype male), YY (super male, phenotype male). These two types of phenotypically undistinguishable males were back-crossed to normal XX-females resulting again in either a 1:1 sex ratio (for XY-males) or in all-male broods (for the YY-male). Pink and blue outer circles denote phenotypic females and males, respectively.

Crossings of sex-reversed XY fish (phenotypic females) with normal, XY-males should lead to the following types and proportion of offspring: one quarter of XX-females, two quarters of XY-males and one quarter of YY-males (super-males) (Figure 2). Note that, morphologically, the two types of males should be undistinguishable.

Subsequent crossings of all males of one of the broods with a 1:3 sex ratio to normal females revealed one male that only produced male offspring, suggesting that it is indeed a YY-male, lending further support to an XX/XY sex determination system in this species.

Expression profiles of sexual development genes

We crossed the YY-super-male to XX-females to produce all-male broods, which we used to investigate expression patterns of sex differentiation genes during early male development. In similar experiments in the Nile tilapia, the spurious occurrence of females in the offspring of super-males has been reported [41]. To allow a potential detection of such spontaneously occurring phenotypic females in these broods, gene expression was measured in individual samples rather than pooling samples. To our knowledge, this is the first study that used a large number of individual samples in a dense sampling scheme for establishing the gene expression profiles of a set of candidate genes for sexual development (24 genes tested in 88 individuals sampled at 22 time points during a period of 40 days). Fish were dissected from the yolk and separated in head and trunk, as proxies for developing brain and gonad. Single organ dissection is not possible at these early stages of development, especially if gene expression is to be accessed on an individual basis. The chosen approach has already successfully been applied in other species [5,7,42-47].

The relative expression of a set of candidate genes, previously tested in brain and gonad tissue of adult cichlid fishes [11], plus one additional gene, gsdf, was profiled during male development. These genes are candidates for sex determination and differentiation as suggested by their described function in fish and tetrapods. This gene list includes, wherever existing, the two paralogous gene copies emerging from the fish-specific whole-genome duplication [48].

The brain and the gonads are the main tissues acting in sexual development. In addition, sexually dimorphic expression can be observed in the brain even earlier than in the gonad, a pattern already described in cichlids [43,49]. Samples were taken between 7 and 48 dpf, with a daily sampling at the beginning of the experiment (7 – 20 dpf) and then every third (during 20 – 38 dpf) and afterwards every fifth day (38 – 48 dpf,) as day-to-day changes are more prominent early in development [36]. We then used the Fluidigm system to test the expression of the 24 candidate genes. Gene expression was calculated as fold change in gene expression using the delta-delta-CT method [50], compared to expression in a juvenile tissue pool (Figure 3 and Additional file 1) or relative to the mean of the four biological replicates at the first sampling point at 7 dpf (Additional file 2). For each sampling point the fold change in gene expression in heads and trunks of four individuals was calculated. For details on sample sizes for each gene see Additional file 3.

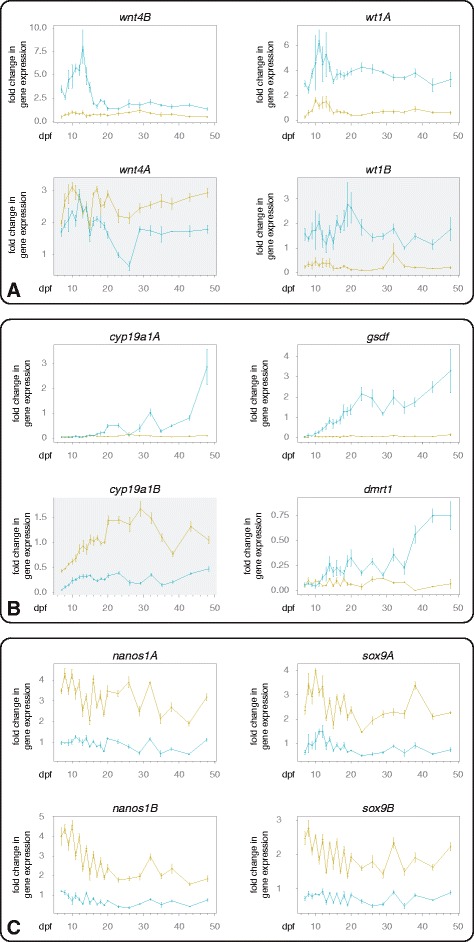

Figure 3.

Gene expression of sexual development genes in heads and trunks of developing male A. burtoni . (A) Wnt4B and wt1A were the only detected early testis genes, here shown with their paralogous gene copies wnt4A and wt1B (grey background). (B) Cyp19a1A, gsdf and dmrt1 are examples of late testis genes, cyp19a1B is the teleost specific paralog of cyp19a1A (grey background). (C) Nanos1A, nanos1B, sox9A and sox9B are examples for brain genes. Gene expression is shown as fold change (Livak) ± SE in heads (green) and trunks (blue) from 7 – 48 dpf using rpl7 as reference gene and a juvenile tissue mix as reference tissue (see Additional file 3 for further details).

The expression profile of a known testis-specific gene (dmrt1) in all tested trunks strongly suggests that all individuals were indeed males and that none of the offspring was a female. In addition, we raised fish that were not used for the gene expression experiment to adulthood/maturity and confirmed that all of them were males. We hence did not detect any occurrence of spurious females.

We investigated gene expression patterns according to the expression profiles explained in Figure 1 and compared expression between heads and trunks. Figure 3 shows the most prominent examples for the expression profiles early testis genes, late testis genes and (early) brain genes (for all expression profiles see Additional files 1 and 2). In the following, we describe the results in more detail.

Testis and brain markers

From all 24 candidate genes, only wnt4B and wt1A are likely to represent early testis genes, i.e., showing a peak in expression early in development and in trunks only (Figure 3A, corresponding to the profile shown in Figure 1A). Cyp19a1A, gsdf and dmrt1 appeared as late testis genes with an increase in trunk expression over time (Figure 3B, corresponding to the profile shown in Figure 1B). Gata4 showed a similar increase in expression in trunks starting earlier as the other genes, around 15 dpf (see Additional file 1). In total, we detected 12 ‘brain’ genes (ctnnb1A, ctnnb1B, cyp19a1B, dax1A, foxl2A/foxl2, foxl2B, nanos1A, nanos1B, rspo1, sf-1, sox9A and sox9B). For illustration purposes, we show the results for both gene copies of wnt4, wt1 and cyp19a1 in Figure 3.

Wnt4A and wnt4B – different fates for gene copies

Wnt4A showed higher expression levels in heads than in trunks, whereas wnt4B showed the opposite signature with a higher expression in trunks than in heads. Also in adult males, wnt4A is significantly higher expressed in brain compared to testis tissue [11]. In adult cichlids, there is a detectable difference in gene expression between the two paralogs of wnt4, with the A-copy being ovary- and the B-copy being testis-specific [11]. Wnt4B was one of only two genes with the earliest peak of expression in trunks (7 – 15 dpf), resembling the pattern of a sex-determining gene.

Wt1A and wt1B – testis genes with different temporal patterns

Wt1A and wt1B are both higher expressed in trunks than in heads throughout the experimental time period, which is congruent with the pattern observed in adult males of A. burtoni [11]. Wt1A is the second gene that showed an expression peak in trunks at the beginning of development (between 7 and 15 dpf) but in contrast to wnt4B at the same time point also an increase of expression in heads (Figure 3A).

Dmrt1 and gsdf - late testis genes possibly important for gonad maintenance

Dmrt1 is known as the conserved vertebrate testis gene [51] and also shows testis-specificity in adult A. burtoni [11]. We found similar levels of gene expression in heads and trunks early in development (7 – 11 dpf) followed by an increase (12 – 48 dpf) in expression in trunks only, pointing to a later function in testis development (Figure 3B). In many of the head samples dmrt1 expression could not be detected (see Additional file 3 for details), which is consistent with previous results in adult brains [11].

Gsdf (gonadal soma-derived factor) is a sexual development gene only existing in fish [52], which has received considerable attention recently. In the above-mentioned O. luzonensis, Y- and X-chromosome specific alleles have been identified for this gene (gsdfYand gsdfX, respectively), with the former turning out to be the master sex determiner in this species [5]. In another species, the sablefish Anoplopoma fimbria, gsdf seems to be a strong candidate for the sex-determining locus, too [53]. Furthermore in medaka, gsdf expression has been implicated with early testicular differentiation [54].

In A. burtoni the expression profile of gsdf resembled that of dmrt1, with a constant increase of expression in trunks after a short time of low expression (7–10 dpf), and constant low expression in heads (Figure 3B). Just as for dmrt1, in some of the head samples, gsdf expression could not be detected (see Additional file 3 for details).

The aromatases cyp19a1A and cyp19a1B

The expression pattern of the aromatase cyp19a1A in the heads remained similar over time whereas its expression in trunks increased constantly. The expression of cyp19a1B was always higher in heads than in trunks, with an increase in expression in both tissues during 7 – 11 dpf, followed by a stable period (12 – 43 dpf), and then the expression in trunks increased again (48 dpf). The expression pattern of cyp19a1A in adults of A. burtoni in brain and gonad tissue shows no difference, and the expression pattern of cyp19a1B shows a significant testis-specific over-expression [11]. In developing A. burtoni males, cyp19a1A seems to play a role in the gonads. The testis-specific expression of cyp19a1B seen in adults only becomes established after 48 dpf, with a start of rising expression detected in our experiments after 40 dpf.

Markers of the developing brain

As mentioned above, we detected 12 ‘brain’ genes. The strongest differences in expression between heads and trunks, and hence likely representing brain up-regulated genes, were found for nanos1A, nanos1B, sox9A and sox9B (Figure 3C). This is consistent with the expression patterns seen in adult males of A. burtoni, where a significantly higher expression in brain tissue than in the testis has been found [11]. The expression level of nanos1B in heads was highest at 7 dpf and then decreased (comparable to Figure 1C, dashed line). Sox9, similar to dmrt1, is considered a prominent example for a gene generally involved in testis formation and function [55,56]. However, this does not seem to be the case in developing and adult A. burtoni.

Investigation of the early testis markers: Sequence and promoter analysis of wnt4B and wt1A

As the wnt4B and wt1A expression showed a peak early in development (7 – 15 dpf) and then decreased to a constantly low level, thus mimicking the expression of a potential sex determination gene, we decided to investigate these genes’ sequences in detail in A. burtoni. For wnt4B, we sequenced the entire genic region, whereas for wt1A we focused on the coding region only, due to the large size of the region (~ 20 kb). A sequence comparison of the coding region of males and females did not show any allelic differences between the sexes for both genes. Also the intronic sequences of wnt4B did not show any sex-specific differences. However, gene expression could still be differently regulated due to sex-specific changes in the promoter region of the genes. To identify the potential promoter regions of wnt4B and wt1A we compared the upstream sequences of the two genes in the accessible teleost fish genomes using Vista plots of nucleotide similarity [57,58] (Figures 4 and 5). The 5’ neighboring gene to wnt4B is chd4b, which is located ~13 kb upstream. We created VistaPlots comprising this entire region. The next annotated gene 5' of wt1A is more than 50 kb upstream. We thus decided to focus our analysis on the region 20 kb upstream to wt1A.

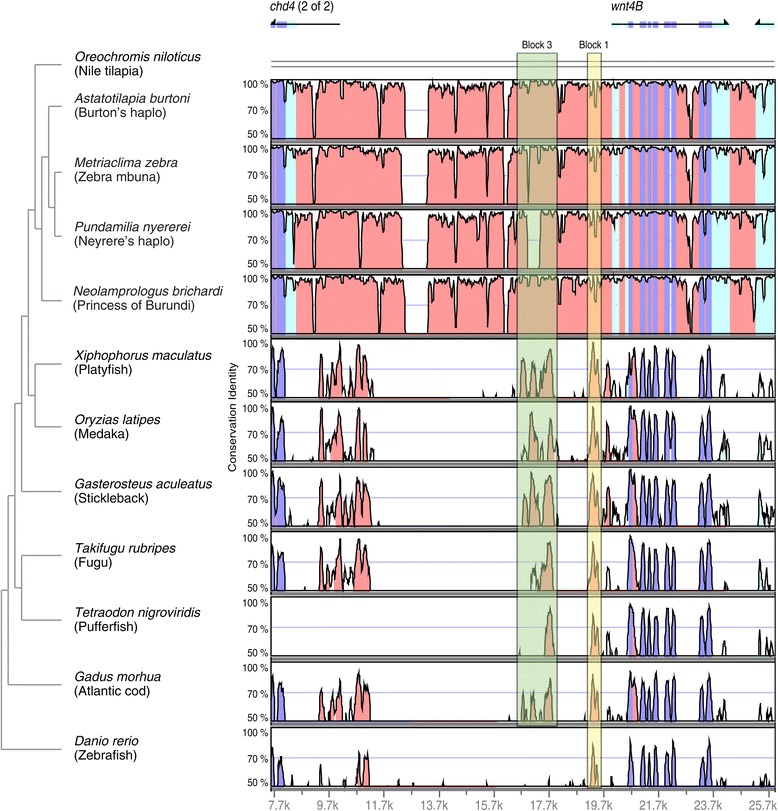

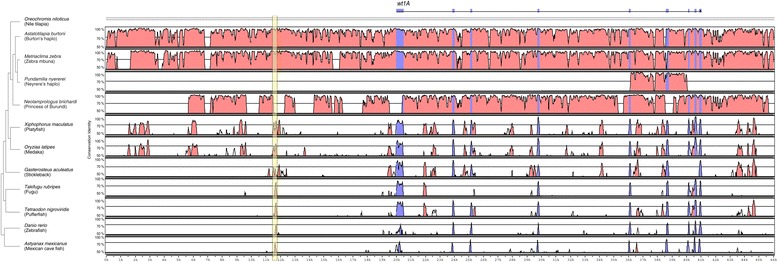

Figure 4.

Comparison of the wnt4B upstream region. Shuffle-LAGAN Vista plots [57,58] for wnt4B and its 5' adjacent gene chd4. Peaks indicate conservation identity of sequences above 50% across the tested species. Blue stands for coding and pink for noncoding regions, respectively. Light blue regions represent UTRs. Yellow block 1 and green block 2 were investigated in the process of transcription factor binding site analysis (Table 1).

Figure 5.

Comparison of the wt1A upstream region. Shuffle-LAGAN Vista plots [57,58] for wt1A. Peaks indicate conservation identity of sequences above 50% across the tested species. Blue stands for coding and pink for noncoding regions, respectively. The yellow block was investigated in the process of transcription factor binding site analysis (Table 2).

In an additional step, after in silico definition of a core conserved upstream region of wnt4B (see colored blocks in Figure 4), we sequenced ~ 7 kb of this promoter in A. burtoni males and females of our lab strain. We also obtained ~ 4 kb upstream sequence for wt1A. Again, no differences between the sexes were found in the upstream regions of wnt4B and wt1A. For wt1A we detected two alleles with one of them having a 223 bp deletion compared to the reference genome. However, neither the deletion nor any other detected heterozygous site segregated with sex.

Transcription factor binding-sites in wnt4B and wt1A potential promoters

To identify genes regulating wnt4B and wt1A expression and, thereby, possibly being more upstream in the sex-determining cascade, we performed a transcription factor binding-site analysis of the two conserved regions in wnt4B (blocks 1 and 2 in Figure 4) and the one conserved region in wt1A (yellow block in Figure 5) using MatInspector. We focused on transcription factors with a described function in gonads, germ cells, brain and/or central nervous system and compared the putative binding sites of A. burtoni with the ones present in all other available fish genomes. Tables 1 and 2 show all putative binding-sites detected in the A. burtoni sequence and indicate, in which other species these sites have been detected (for a complete table with all putative transcription factor binding-sites including non-conserved sites in all tested species, see Additional files 4 and 5).

Table 1.

Predicted transcription factor binding sites in the wnt4B promoter region of A. burtoni

| Block 1 | Block 2 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. burtoni | X. maculatus | O. latipes | G. aculeatus | T. rubripes | T. nigroviridis | G. morhua | D. rerio | A. burtoni | X. maculatus | O. latipes | G. aculeatus | T. rubripes | T. nigroviridis | G. morhua |

| AR | AR | x | ||||||||||||

| E4BP4 | x | x | x | x | x | x | Creb | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Ets1 | x | Creb1 | x | x | ||||||||||

| Foxa-1 and 2 | x | x | x | x | x | x | Dbp | |||||||

| Foxk2 | x | x | x | Dec2 | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| Gsh2 | Egr1 | x | x | |||||||||||

| Helt | ESRRA | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Isl1 | Evi1 | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| Meis1 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | FAC1 | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Myt1 | x | x | x | x | x | x | FoxC1 | |||||||

| Pax6 | Hmx2 | x | x | |||||||||||

| Plag1 | x | x | x | x | x | Hmx3 | x | x | ||||||

| Satb1 | Hre | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Sox6 | x | x | x | x | Ir1 | |||||||||

| Spi1 | x | x | x | x | x | x | Irx5 | x | x | |||||

| Tef | x | x | x | x | x | x | Mef3 | x | ||||||

| Meis1 | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| MEL1 | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| Myf5 | x | |||||||||||||

| Myf6 | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| Nanog | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| NF1 | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Nkx2-5 | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| Nkx6-1 | x | |||||||||||||

| Nur-Family | x | x | ||||||||||||

| Pax4 | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| Plag1 | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| Pou5f1 | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| Rfx4 | x | x | ||||||||||||

| Rfx7 | x | |||||||||||||

| SF1 | x | x | ||||||||||||

| Sox3 | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| Sox30 | x | x | ||||||||||||

| Sox6 | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| Ttf1 | ||||||||||||||

| Wt1 | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Ybx1 | ||||||||||||||

| Zfp67 | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| Zic2 | x | x |

Blocks correspond to the green and yellow regions in Figure 4. Bold binding sites are shared with at least one other species. "x" denotes the detection of the binding site in the respective species.

Table 2.

Predicted transcription factor binding-sites in the wt1A promoter region of A. burtoni

| A. burtoni | M. zebra | N. brichardi | O. niloticus | X. maculatus | O. latipes | G. aculeatus | T. rubripes | T. nigroviridis | D. rerio | A. mexicanus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AP1 | x | x | x | |||||||

| ATF1 | x | x | ||||||||

| ATF6 | x | x | x | |||||||

| Atoh1 | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Barx1 | x | x | x | |||||||

| Bcl6b | x | x | x | |||||||

| Creb | x | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Creb1 | x | x | x | |||||||

| Dlx2 | x | x | x | |||||||

| Dlx3 | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| Dmrt2 | x | x | x | |||||||

| dre | x | x | ||||||||

| E2a | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Elf3 | x | x | x | x | x | |||||

| eng1a | x | x | ||||||||

| eng2a | x | x | x | |||||||

| Evi1 | x | x | x | x | x | |||||

| FAC1 | x | x | ||||||||

| Fkhrl1 | x | x | x | |||||||

| Foxa1 | x | x | ||||||||

| Foxp1 | x | x | x | |||||||

| foxp2 | x | x | ||||||||

| gli3 | x | x | x | |||||||

| gr | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| Gsh2 | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| Hif1 | x | x | x | |||||||

| hlf | x | |||||||||

| HOX/PBX binding sites | x | x | x | |||||||

| hoxb9 | x | x | x | |||||||

| ISL LIM homeobox 2 | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| Isx | x | x | x | |||||||

| lhx2b | x | x | ||||||||

| Meis1 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Meis1b and Hoxa9 heterodimeric complexes | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| MEL1 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Myf5 | x | x | x | |||||||

| MyoD | x | x | ||||||||

| Nk2-3 | x | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Nkx2-5 | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Nkx2-9 | x | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Nkx5-1 | x | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Nobox | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| nr2c1 | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||

| nrf2 | x | x | ||||||||

| nrsf | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| Pax6 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| pce1 | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| Plag1 | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| Pou3f2 | x | x | ||||||||

| S8 | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| six1b | x | x | ||||||||

| Sox6 | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Tax/CREB complex | x | x | x | |||||||

| Tgif | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| Zfp67 | x | x | x | x | x |

Shown are binding sites in the conserved region marked in yellow in Figure 5. Bold binding sites are shared with at least one other species. "x" denotes the detection of the binding site in the respective species.

Interestingly, we identified several conserved binding sites for transcription factors that have been implicated with sexual development before. For wnt4B we found that six out of seven species show a conserved putative binding site for Wt1 in block 2 (Table 1). This fits well with our own expression data (Figure 3) as well as other studies in fish [59,60], which support an involvement of wt1A in early testis formation. Other promising upstream candidates of wnt4B are Sox30 and the androgen receptor (AR). Sox30 is expressed specifically in gonads of the Nile tilapia, with one isoform being even limited to the developing testis [61]. The androgen receptor can bind testosterone and dihydrotestosterone and thereby plays an important role in controlling male development [62]. Interestingly, ar is higher expressed in brains of dominant A. burtoni males than in subordinate males [63]. In the developing gonads of the Nile tilapia the expression levels of ar in males and females are similar [17].

Remarkably, we found putative transcription factor binding sites for two of our candidate genes: wt1 (discussed above and Figure 3A) and sf-1 (Additional file 1). However, the expression pattern of sf-1 in developing testis (expression in trunks) does not support its putative role as a direct regulator of wnt4B, as it was expressed at low levels during the experimental time period (Additional file 1). The expression profiles in heads, on the other hand, showed high expression at the beginning (7 – 12 dpf), with a constant decrease afterwards (as in Figure 1C, dashed line; and Additional file 1). Sf-1 might thus be an example of an early brain gene influencing sexual development via other factors than wnt4B.

In contrast to wnt4B, we could identify only one small conserved block upstream of wt1A. We did not find a binding-site for any of our candidate genes or an obvious transcription factor already known to play a role in sexual development or any binding site only present in A. burtoni in that block. However, we found a broad range of neuronal transcription factors and binding sites for members of the dm-domain family, here dmrt2, which might have a female sex-specific role in adult cichlids [64]. As for wnt4B, we also found a binding site for a Sox-family member, here Sox6.

Interestingly, we found binding sites for several members of the forkhead transcription factor family (Foxa1, Foxp1, Fkhrl1 alias Foxo3 and Foxp1), which are known as regulators of development and reproduction. Together with foxl2 and foxl3, they were also among the candidate genes in our expression assay.

Discussion

Here we provide first experimental proof for a male sex-determining (XX-XY) system in the haplochromine cichlid Astatotilapia burtoni, making use of hormonal sex-reversal and the subsequent generation of mono-sex broods. Offspring from male-only broods were investigated for gene expression patterns to define the window of sex determination in A. burtoni, which seems to take place at 11–12 dpf.

Throughout larval development, we decided to investigate gene expression in whole heads and trunks, including also other tissues than brains and gonads. Similar studies have been conducted in the Nile tilapia, which revealed that expression of sexual development genes in brains and testis is comparable to the one in heads and trunks, respectively [42,43].

We chose this approach in order to assess the individual gene expression level rather than pooling samples. Furthermore, the timing of morphological development, especially of gonads but also brain structures, is unknown in A. burtoni and no marker of gonad differentiation is available for this species, making an early single tissue dissection physiologically and technically impossible. By using whole trunks we made sure that we did have testis tissue in our samples starting from the onset of gonad formation. Another reason why it was important to test gene expression on an individual level is the possible occurrence of spurious XY-females in offspring derived from super-males, which has been described for other cichlids [41,65]. Furthermore, the sex determining gene(s) are not yet identified in A. burtoni and additional minor factors influencing sexual fate (environmental or genetic) cannot be ruled out.

After careful inspection of all raw and analyzed data, we did not find any evidence of females in the broods sired by the super-male, i.e., there was no individual with opposing expression patterns at a given sampling point. Especially the expression of the conserved testis factor dmrt1 in the trunks is a good indicator for male gonad functioning, which is also evidenced by similar profiles in the Nile tilapia (increase in expression of dmrt1 in testis [17]). A developing ovary would likely have contradicted this trend in gene expression.

Concerning the heads, we cannot rule out the possibility that the expression in other tissues than the brain is picked up by our experiment. For example, if the expression level of a gene is higher in eyes than in testis and higher in testis than in brains (corresponding to: “eyes > testis > brains”), then the overall head expression would be higher compared to trunks (and hence lead to the wrong classification into a brain gene). Having a closer look at the 12 "brain genes" identified by our approach, they either still show a higher expression in the brain than the testis in adult A. burtoni (eight genes) or have the reversed expression pattern in adults (four genes) [11]. Thus, the expression levels that we measured in the heads for these four genes (dax1A, foxl2B, sf1 and cyp19a1B) might not be truly brain specific. Alternatively, the expression pattern may change later in development with an up-regulation in testis and/or down regulation in brain. We think that the latter is more likely, since foxl2B, sf1 and cyp19a1B indeed showed a late increase in trunk/testis expression in our experiment, which might further increase beyond the period tested here.

Comparing between gene expression patterns within our experiment, we can show, once more, that paralogous gene copies derived from the fish specific whole genome duplication can evolve different functions, reflected by differences in tissue specificity. In our dataset this is true for wnt4A and B and cyp19a1A and B, with each of them having one copy being over-expressed in the heads and one in the trunks. However, we also observed a retention of the same (and hence probably ancestral) expression pattern in both gene copies, for example with very similar expression patterns for nanos1A and B and sox9A and B, which is also true in the adult stage [11].

Our main goal was to identify genetic markers for the time window of sex determination in A. burtoni. This critical time period, in which the decision if the bipotential embryonic gonad develops towards ovaries or testes is made, has so far been characterized in only one cichlid, the Nile tilapia, where it takes place at 9 to 15 dpf [17,34]. The trunk expression peaks of wt1A and wnt4B at 11 and 12 dpf suggested that also in A. burtoni the time window of sex determination takes place early in development, before any major signs of differentiated gonads become visible. In addition, the narrowness of the expression peak indicated that this time window is rather short. Note that our initial hormone treatment roughly started at the same time point likely accounting for the successful 100% sex reversal.

From the two genes with this early expression peak, especially wnt4 received some attention in the research of sex determination. Female up-regulation or male down-regulation of wnt4 expression have been described to be important for promoting ovarian development and function in mammals [66-68]. Also in the developing male gonad wnt4 is needed for Sertoli cell differentiation, a crucial step for testis determination [69]. Still, data from teleost fish are largely lacking for wnt4 and especially for the two teleost paralogs.

Wt1 plays a role in testis differentiation and sex determination in mammals [70,71]. In the medaka, both genes, wt1a and b, are important for primordial germ cell maintenance, a crucial regulatory mechanism in gonad differentiation in fish [72]. In the Nile tilapia, wt1a is up-regulated in the developing male gonad [59]. Hence, wt1 might act early in gonad differentiation also in other species.

Our sequence analysis of coding and promoter sequence of wnt4B and wt1A did not reveal any nucleotide difference associated with sex and thus ruled out the two genes as initial genetic regulator of sex determination in A. burtoni. However, it is very likely that they represent one of the first members of the sex determination network to be activated during the critical time point of sex determination. Interestingly, the promoter sequence of wnt4B contains a potential binding site for wt1, meaning that the two genes might functionally interact. Our promoter analysis further suggested that the androgen receptor (ar), steroidogenic factor 1 (sf1) and sox3, three genes with a well-described function in male specific processes [70,73], might regulate wnt4B expression. Note that ar has two predicted binding-sites in the wnt4B promoter, with one being species-specific to A. burtoni, and that sox3 has been co-opted as a master sex-determining gene in another fish species [6]. We did not detect any such obvious candidate among the possible transcriptional regulators of wt1A.

Conclusion

In this study, we investigated the expression profiles of sexual development genes in the East African cichlid fish Astatotilapia burtoni during early male development. Based on hormonal treatment and subsequent crossing experiments we provided evidence that a male master determiner defines sex in A. burtoni. We identified early testis genes, late testis genes and male brain genes (Figures 1 and 3). The earliest testis markers wnt4B and wt1A were investigated in more detail, as they are strong candidates for the role of the sex-determining gene in A. burtoni, due to their expression pattern. Genomic sequences of males and females showed no differences, neither in the coding nor in their promoter region, ruling them out as an initial genetic male determiner. Nonetheless, we suggest that both have an important function early in the sexual development cascade and might even be one of the first targets of the still unknown sex determination factor. A transcription factor binding site analysis revealed possible candidates for master regulators of sexual development in A. burtoni such as sox30, ar and sf-1. Future investigations of these candidates, including sequence and expression analyses, together with similar gene expression experiments in female A. burtoni should shed more light on the complex cascade of sexual development to finally uncover the master sex-determining gene in this model cichlid species.

Methods

All experiments involving animals were performed in accordance with public regulations under the permits no. 2317 and no. 2620 issued by the cantonal veterinary office of the canton Basel-Stadt (Switzerland).

Estrogen treatment

Animals used in this study were derived from a lab strain of the species A. burtoni, an East African cichlid fish from Lake Tanganyika and its surrounding affluent rivers, reared at the fish facility of the Zoological Institute of the University of Basel at 24°C with a 12 hours dark–light cycle.

We treated four clutches of A. burtoni with 17α-EthynylEstradiol (E-4876, Sigma) for feminization (protocol kindly provided by H. D’Cotta; see also [1]). 15 mg 17α-EthynylEstradiol were dissolved in 100 ml of 100% ethanol, poured onto 100 g flake food (sera vipan®) and dried at 37°C. From 14 dpf (which is the date when the first fish in the clutches started feeding after the yolk had been absorbed) fish were fed three times a day during four weeks with the hormone treated food. Feeding with 17α-EthynylEstradiol treated food resulted in 100% morphological females in all broods. Amongst these morphological females, we expected (assuming an XX-XY sex determination system) that roughly half of the individuals would have an XX (female) and the other half an XY (male) genotype. Treated fish were subsequently crossed with untreated, normal males. Among the offspring of these individual crossings, several broods showed a 1: 3 (female : male) sex ratio indicative of an XY genotype of the mother (feminized genetic male). Of these crosses, all male offspring was further crossed to normal females. One of these crosses resulted in all male offspring, suggesting that the father was a YY-supermale. For an overview of the crossing design see Figure 2.

Tissue sampling

The potential YY-male resulting from the above mentioned experiment was crossed to untreated females of the lab strain to produce all-male broods. The resulting eggs were collected within an hour after fertilization from the female’s mouth and incubated in an Erlenmeyer at 24°C with constant airflow in a 12 hours dark–light cycle. Four individuals were sampled at each of the sampling points at the following days post fertilization: 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 23, 26, 29, 32, 35, 38, 43 and 48. This sampling scheme, with a denser sampling early in development, was chosen because development progresses faster in early stages compared to later stages [36]. Eight clutches were needed to obtain a total of 88 fish. Individuals were photographed for length measurements with a Leica DFC 310 FX (Leica Microsystems). At these early developmental time points, the sampled fish are too small (~ 5 mm standard length) to dissect single organs. To guarantee sufficient RNA material, we thus separated embryos into heads and trunks as proxies for developing brain and gonad tissue, an approach widely used in other fish species [5,7,42-47]. Dissected tissues were stored in Trizol at −80°C until further proceeding.

RNA extraction, DNase treatment and cDNA synthesis

Thawed samples were homogenized using a FastPrep®24 beat beater (MP Biomedicals Europe). Total RNA was extracted following the Trizol protocol. RNA quality and concentration were measured using a NanoDrop 1000 spectrophotometer (ThermoScientific). The RNA was stored at −80°C until further use. RNA samples were treated with DNA-free™ Kit (LifeTechnologies) as recommended by the manufacturer. DNase-treated RNA was reverse transcribed using the High Capacity RNA-to-cDNA™ Kit (LifeTechnologies) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and diluted to a concentration of 5 ng/μl of cDNA for further procedure.

qRT-PCR expression experiments

In addition to 24 primers (23 candidate genes and rpl7 as a reference gene) described in [11], and to the primers for ef1a and rpsA3 (used as further reference genes, described in [74]) a primer pair for gsdf (as a candidate gene, Forward 5’- CCACCATGGCCTTTGCATTC -3’ and Reverse 5’- TCACAGGTGCCAAGGTGAGT -3’) was designed and validated for A. burtoni following the procedure described in [11] Rpl7, rpsA3 and ef1a were tested as possible reference genes. RpsA3 and rpl7 showed high stability over all samples (whereas ef1a showed slightly more variation). Subsequently, rpl7 was chosen as a reference gene in the analysis of the qRT-PCR experiments.

Prior to the qRT-PCR experiment, a specific target amplification (multiplex-amplification to increase the amount of targets of interest) was carried out as follows: 2.6 μl TaqMan PreAmp Master Mix (LifeTechnologies), 1.3 μl of a 200 nM mix of all primer pairs and 1.3 μl cDNA were pre-amplified in a thermo cycler (LifeTechnologies) (cycling conditions: 1 × 95°C for 10 minutes, 14 × 95°C for 15 seconds and 58°C for 4 minutes) and diluted 1 : 5 with Low EDTA buffer. The sample premix [2.5 μl TaqMan Gene Expression Mastermix (LifeTechnologies), 0.25 μl DNA Binding Dye Loading Reagent (Fluidigm), 0.25 μl Eva Green (Biotium), 0.75 μl Low EDTA buffer, 1.25 μl of cDNA] and the Assay mix [2.5 μl Assay Loading Reagent (Fluidigm), 0.25 μl Low EDTA buffer, 2.25 μl of 20 μM primer pair] were pipetted on a primed 96 × 96 chip and the plate was loaded in the IFC controller both according to Fluidigm protocols. Expression profiles of the candidate genes in heads and trunks of A. burtoni were measured using a Fluidigm BioMark™ assay (HD Systems) at the Genetic Diversity Centre (GDC) of the ETH Zurich with the following cycling conditions: 95°C for 10 minutes, 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds and 58°C for 1 minute. All reactions were followed by a melt curve step to ensure primer specificity and detect possible erroneous amplification. The experiment included three technical replicates of all samples and four biological replicates of all the juvenile samples. Expression data was first analyzed using the Fluidigm Real-Time PCR analysis software to detect technical outliers and for the inspection of melt curves. As outliers we identified samples that showed a deviation from the other samples over all genes, what could easily be seen in the heat map generated by the software. This can happen if an integrated fluidic circuit on the Fuidigm system is blocked by an air bubble. The fold change in expression of the candidate genes in the samples was then calculated with the delta-delta-CT method [50] using custom R scripts. For normalization, the CT values of the reference gene rpl7 and the mean CT value of a juvenile tissue mix were used. In an additional analysis the fold change was calculated and plotted relative to the mean of the four technical replicates at the first sampling point at 7 dpf (Additional file 2).

Wnt4B and wt1A sequencing

DNA from adult males and females of A. burtoni labstrain individuals was extracted from fin clip samples by applying a Proteinase K digestion followed by sodium chloride extraction and ethanol precipitation as described in [75]. To sequence the coding and promoter region of wnt4B, nine primer pairs (one of them with two different reverse primers) were designed based on the A. burtoni genome [39] using GenScript. The genomic region of wt1a spans more than 20 kb in the Nile tilapia genome (over www.ensembl.org) here used as reference for annotation of the wt1a coding sequence in the non-annotated A. burtoni genome. We thus decided to focus on the coding region for sequencing and constructed primer pairs to amplify each of the nine exons. To sequence the potential promoter region of wt1A, six additional primer pairs were constructed covering ~ 4 kb upstream of wt1a. The adjacent annotated gene, depdc7, is located ~55 kb upstream of wt1A in the Nile tilapia genome. PCR reactions were carried out on nine individuals per sex for wnt4A and eight individuals per sex for wt1A using REDTaq DNA Polymerase (Sigma-Aldrich) and Phusion Master Mix (New England Biolabs) (for primer sequences and cycling conditions see Additional file 6). PCR products were visualized with GELRed (Biotium) on 1.5% agarose gels. Fragments were sequenced on a 3130xl capillary sequencer (Applied Biosystems) and alignments were performed with CodonCodeAligner (CodonCode Corporation), manually inspected and compared to the corresponding region in the A. burtoni genome.

Wnt4B and wt1A promoter analysis

Promoter analysis was carried out on the upstream regions of wnt4B and the wt1A sequences of all the available teleost genomes over www.ensembl.org (release 62) and on the cichlid genome sequences of A. burtoni, Neolamprologus brichardi, Orechromis niloticus, Pundamilia nyererei and Metriaclima zebra [39]. For wnt4B we extracted ~13 kb upstream region until it's next neighboring gene, chd4. For wt1A we analyzed ~20 kb upstream sequence. Alignments were done with mVISTA [57,58] using Shuffle-LAGAN as alignment algorithm. The Nile tilapia sequence was used as a reference. Putative transcription factor binding sites for A. burtoni and the sequenced teleost genomes were identified using MatInspecor (Genomatix Software GmbH). We selected transcription factors that showed a matrix similarity > 0.9 and that belonged to one of the following categories: testis, ovary, germ cell, brain and/or central nervous system. Abbreviated names of transcription factors were taken from Genbank. Tables 1 and 2 show all factors detected in A. burtoni and their conservation in the other investigated teleost genomes (indicated by an "x" in Table 1). The complete list with all detected binding sites in all species is shown in Additional files 4 and 5.

Acknowledgements

We thank N. Boileau for support in the lab and A. Minder, K. Eschbach and the GDC at the ETH Zurich for access to the Fluidigm and help during the experiments. The authors thank A. Indermaur, A. Rüegg and Y. Kläfiger for fish keeping. This work was funded by the Forschungsfond Universität Basel, the Volkswagenstiftung (Postdoctoral Fellowship Evolutionary Biology, grant number 86 031), and the DAAD (German academic exchange service, grant number D/10/54114) to AB; and the European Research Council (ERC, Starting Grant “INTERGENADAPT” and Consolidator Grant “CICHLID ~ X”) and the Swiss National Science Foundation to WS.

Abbreviations

- CT

Threshold cycle

- dpf

days post fertilization

- qRT-PCR

quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

- RT

Room temperature

- UTR

Untranslated region

Additional files

Expression data of additional sexual development genes during development of A. burtoni . Gene expression as fold change (Livak) ± SE in heads (light green) and trunks (dark blue) from 7 – 48 dpf using rpl7 as reference gene and a juvenile tissue mix as reference tissue. For details on sample size see Additional file 3.

Expression data of all candidate genes during development of A. burtoni . Gene expression as fold change (Livak) ± SE in heads and trunks relative to the first sampling point at 7 dpf. For details on sample size see Additional file 3.

Sample sizes for qRT-PCR experiment if other than four. Sample size of trunks at 8, 10 and 11 dpf is three for all genes (and two for wnt4B) and therefore not depicted here. Besides sf-1 (trunk tissue of three individuals at 12 and 13 dpf) and gata4 (head tissue of three individuals at 38 dpf) all the missing data can be accounted to not detectable expression of dmrt1 and gsdf in heads.

Putative transcription factor binding sites in the conserved promoter regions (block 1 and block 2 as in Figure 4 ) of wnt4B in teleost genomes. We chose transcription factors with a Matrix similarity > 0.9 and described in the tissues testis, ovary, germ cells, brain and/or central nervous system. Included species are A. burtoni, Xiphophorus maculatus, Oryzias latipes, Gasterosteus aculeatus, Takifugu rubripes, Tetraodon nigroviridis, Gadus morhua and Danio rerio for block 1 and without Danio rerio for block 2. Abbreviated names of transcription factors were taken from Genbank.

Putative transcription factor binding sites in the conserved promoter region (yellow block in Figure 5 ) within 20 kb upstream of wt1A in teleost genomes. We chose transcription factors with a Matrix similarity > 0.9 and described in the tissues testis, ovary, germ cells, brain and/or central nervous system. Included species are A. burtoni, Metriaclima zebra, Neolamprologus brichardi, Oreochromis niloticus, Xiphophorus maculatus, Oryzias latipes, Gasterosteus aculeatus, Takifugu rubripes, Tetraodon nigroviridis, Danio rerio and Astyanax mexicanus. Abbreviated names of transcription factors were taken from Genbank.

Primer sequences and cycling conditions used for sequencing of wnt4B and wt1A coding and promoter sequence. For amplicon six of wnt4B a second reverse primer (reverse 6_2) was designed closer towards forward 6 to ensure complete sequencing of this DNA stretch.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

AB and WS designed the study, AB, WS and CH wrote the manuscript. CH and AB performed hormone treatments and crossings. CH performed the qRT-PCR expression and wnt4B sequence analysis. CH and AB conducted the promoter and transcription factor binding site analysis. CG sequenced wt1A coding and promoter regions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

CH was a PhD student, CG is a master student and AB is a postdoctoral researcher in the group of WS. CH, CG and AB investigate sex determination and differentiation and their evolution in teleost fish using cichlids as a model system. WS is a Professor of Zoology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Basel. He and his team focus on the genetic basis of adaptation, evolutionary novelties and diversification mainly in cichlid fishes.

Contributor Information

Corina Heule, Email: co.heule@unibas.ch.

Carolin Göppert, Email: c.goeppert@stud.unibas.ch.

Walter Salzburger, Email: walter.salzburger@unibas.ch.

Astrid Böhne, Email: astrid.boehne@unibas.ch.

References

- 1.Devlin RH, Nagahama Y. Sex determination and sex differentiation in fish: an overview of genetic, physiological, and environmental influences. Aquaculture. 2002;208(3):191–364. doi: 10.1016/S0044-8486(02)00057-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cutting A, Chue J, Smith CA. Just how conserved is vertebrate sex determination? Dev Dyn. 2013;242(4):380–387. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.23944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsuda M, Nagahama Y, Shinomiya A, Sato T, Matsuda C, Kobayashi T, Morrey CE, Shibata N, Asakawa S, Shimizu N, Hori H, Hamaguchi S, Sakaizuma M. DMY is a Y-specific DM-domain gene required for male development in the medaka fish. Nature. 2002;417:559–563. doi: 10.1038/nature751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nanda I, Kondo M, Hornung U, Asakawa S, Winkler C, Shimizu A, Shan Z, Haaf T, Shimizu N, Shima A, Schmid M, Schartl M. A duplicated copy of DMRT1 in the sex-determining region of the Y chromosome of the medaka, Oryzias latipes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(18):11778–11783. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182314699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Myosho T, Otake H, Masuyama H, Matsuda M, Kuroki Y, Fujiyama A, Naruse K, Hamaguchi S, Sakaizumi M. Tracing the emergence of a novel sex-determining gene in medakaOryzias luzonensis. Genetics. 2012;191(1):163–170. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.137497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takehana Y, Matsuda M, Myosho T, Suster ML, Kawakami K, Shin-I T, Kohara Y, Kuroki Y, Toyoda A, Fujiyama A, Hamaguchi S, Sakaizumi M, Naruse K. Co-option of Sox3 as the male-determining factor on the Y chromosome in the fish Oryzias dancena. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4157. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hattori RS, Murai Y, Oura M, Masuda S, Majhi SK, Sakamoto T, Fernandino JI, Somoza GM, Yokota M, Strüssmann CA. A Y-linked anti-Müllerian hormone duplication takes over a critical role in sex determination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(8):2955–2959. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018392109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kamiya T, Kai W, Tasumi S, Oka A, Matsunaga T, Mizuno N, Fujita M, Suetake H, Suzuki S, Hosoya S, Tohari S, Brenner S, Miyadi T, Venkatesh B, Suzuki Y, Kikuchi K. A trans-species missense SNP in amhr2 is associated with sex determination in the tiger pufferfish, Takifugu rubripes (Fugu) PLoS Genet. 2012;8(7):e1002798. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yano A, Guyomard R, Nicol B, Jouanno E, Quillet E, Klopp C, Cabau C, Bouchez O, Fostier A, Guiguen Y. An immune-related gene evolved into the master sex-determining gene in rainbow trout,Oncorhynchus mykiss. Curr Biol. 2012;22(15):1423–1428. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yano A, Nicol B, Jouanno E, Quillet E, Fostier A, Guyomard R, Guiguen Y. The sexually dimorphic on the Y-chromosome gene (sdY) is a conserved male-specific Y-chromosome sequence in many salmonids. Evol Appl. 2013;6(3):486–496. doi: 10.1111/eva.12032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Böhne A, Heule C, Boileau N, Salzburger W. Expression and sequence evolution of aromatase cyp19a1 and other sexual development genes in East African cichlid fishes. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30(10):2268–2285. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herpin A, Adolfi MC, Nicol B, Hinzmann M, Schmidt C, Klughammer J, Engel M, Tanaka M, Guiguen Y, Schartl M. Divergent expression regulation of gonad development genes in medaka shows incomplete conservation of the downstream regulatory network of vertebrate sex determination. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30(10):2328–2346. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hornung U, Herpin A, Schartl M. Expression of the male determining gene dmrt1bY and its autosomal coorthologue dmrt1a in medaka. Sex Dev. 2007;1(3):197–206. doi: 10.1159/000102108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rossi P, Dolci S, Albanesi C, Grimaldi P, Geremia R. Direct evidence that the mouse sex-determining gene Sry is expressed in the somatic cells of male fetal gonads and in the germ cell line in the adult testis. Mol Reprod Dev. 1993;34(4):369–373. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1080340404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Turner ME, Martin C, Martins AS, Dunmire J, Farkas J, Ely DL, Milsted A. Genomic and expression analysis of multiple Sry loci from a single Rattus norvegicus Y chromosome. BMC Genet. 2007;8:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-8-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Veith AM, Schafer M, Kluver N, Schmidt C, Schultheis C, Schartl M, Winkler C, Volff JN. Tissue-specific expression of dmrt genes in embryos and adults of the platyfish Xiphophorus maculatus. Zebrafish. 2006;3(3):325–337. doi: 10.1089/zeb.2006.3.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ijiri S, Kaneko H, Kobayashi T, Wang D-S, Sakai F, Paul-Prasanth B, Nakamura M, Nagahama Y. Sexual dimorphic expression of genes in gonads during early differentiation of a teleost fish, the Nile tilapia Oreochromis niloticus. Biol Reprod. 2008;78(2):333–341. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.107.064246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herpin A, Schartl M. Dmrt1 genes at the crossroads: a widespread and central class of sexual development factors in fish. FEBS J. 2011;278(7):1010–1019. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lange IG, Hartel A, Meyer HHD. Evolution of oestrogen functions in vertebrates. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2002;83(1–5):219–226. doi: 10.1016/S0960-0760(02)00225-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakamura M. The mechanism of sex determination in vertebrates - are sex steroids the key-factor? J Exp Zool A Ecol Genet Physiol. 2010;313(7):381–398. doi: 10.1002/jez.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Angelopoulou R, Lavranos G, Manolakou P. Sex determination strategies in 2012: towards a common regulatory model? Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2012;10(1):13. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-10-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morohashi K, Baba T, Tanaka M. Steroid hormones and the development of reproductive organs. Sex Dev. 2013;7(1–3):61–79. doi: 10.1159/000342272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heule C, Salzburger W, Böhne A. Genetics of sexual development – an evolutionary playground for fish. Genetics. 2014;196(3):579–591. doi: 10.1534/genetics.114.161158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salzburger W. The interaction of sexually and naturally selected traits in the adaptive radiations of cichlid fishes. Mol Ecol. 2009;18:169–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kocher TD. Adaptive evolution and explosive speciation: the cichlid fish model. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5(4):288–298. doi: 10.1038/nrg1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Santos ME, Salzburger W. How cichlids diversify. Science. 2012;338(6107):619–621. doi: 10.1126/science.1224818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salzburger W, Van Bocxlaer B, Cohen AS. The ecology and and evolution of the African Great Lakes and their faunas. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst. 2014;5:19–45. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baroiller JF, D’Cotta H, Saillant E. Environmental effects on fish sex determination and differentiation. Sex Dev. 2009;3(2–3):118–135. doi: 10.1159/000223077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reddon AR, Hurd PL. Water pH during early development influences sex ratio and male morph in a West African cichlid fish, Pelvicachromis pulcher. Zoology (Jena) 2013;116(3):139–143. doi: 10.1016/j.zool.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roberts RB, Ser JR, Kocher TD. Sexual conflict resolved by invasion of a novel sex determiner in Lake Malawi cichlid fishes. Science. 2009;326(5955):998–1001. doi: 10.1126/science.1174705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ser JR, Roberts RB, Kocher TD. Multiple interacting loci control sex determination in lake Malawi cichlid fish. Evolution. 2010;64(2):486–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00871.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parnell NF, Streelman JT. Genetic interactions controlling sex and color establish the potential for sexual conflict in Lake Malawi cichlid fishes. Heredity. 2013;110(3):239–246. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2012.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wirtz Ocana S, Meidl P, Bonfils D, Taborsky M: Y-linked Mendelian inheritance of giant and dwarf male morphs in shell-brooding cichlids. 2014, Proc Biol Sci281(1794): 20140253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Baroiller JF, D'Cotta H, Bezault E, Wessels S, Hoerstgen-Schwark G. Tilapia sex determination: Where temperature and genetics meet. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol. 2009;153(1):30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Theis A, Salzburger W, Egger B. The function of anal fin egg-spots in the cichlid fish Astatotilapia burtoni. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e29878. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fujimura K, Okada N. Development of the embryo, larva and early juvenile of Nile tilapia Oreochromis niloticus (Pisces: Cichlidae) Dev Staging Sys Dev Growth Differ. 2007;49(4):301–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2007.00926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Juntti SA, Hu CK, Fernald RD. Tol2-mediated generation of a transgenic haplochromine cichlid. Astatotilapia burtoni. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e77647. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Al Hafedh YS, Siddiqui AQ, Al-Saiady MY. Effects of dietary protein levels on gonad maturation, size and age at first maturity, fecundity and growth of Nile tilapia. Aquac Int. 1999;7(5):319–332. doi: 10.1023/A:1009276911360. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brawand D, Wagner CE, Li YI, Malinsky M, Keller I, Fan S, Simakov O, Ng AY, Lim ZW, Bezault E, Turner-Maier J, Johnson J, Alcazar R, Noh HJ, Russel P, Aken B, Alfoldi J, Amemiya C, Azzouzi N, Baroiller JF, Barloy-Hubler F, Berlin A, Bloomquist R, Carleton KL, Conte MA, D'Cotta H, Eshel O, Gaffney L, Galibert F, Gante HF, et al. The genomic substrate for adaptive radiation in African cichlid fish. Nature. 2014;513(7518):375–381. doi: 10.1038/nature13726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pandian TJ, Sheela SG. Hormonal induction of sex reversal in fish. Aquaculture. 1995;138:1–22. doi: 10.1016/0044-8486(95)01075-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mair GC, Abucay JS, Abella TA, Beardmore JA, Skibinski DOF. Genetic manipulation of sex ratio for the large-scale production of all-male tilapia Oreochromis niloticus. Can J Fish Aquat Sci. 1997;54(2):396–404. doi: 10.1139/f96-282. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Poonlaphdecha S, Pepey E, Canonne M, de Verdal H, Baroiller JF, D'Cotta H. Temperature induced-masculinisation in the Nile tilapia causes rapid up-regulation of both dmrt1 and amh expressions. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2013;193:234–242. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Poonlaphdecha S, Pepey E, Huang SH, Canonne M, Soler L, Mortaji S, Morand S, Pfennig F, Mélard C, Baroiller JF, D'Cotta H. Elevated amh gene expression in the brain of male tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) during testis differentiation. Sex Dev. 2011;5(1):33–47. doi: 10.1159/000322579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fernandino JI, Hattori RS, Kishii A, Strussmann CA, Somoza GM. The cortisol and androgen pathways cross talk in high temperature-induced masculinization: the 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase as a key enzyme. Endocrinology. 2012;153(12):6003–6011. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haugen T, Almeida FF, Andersson E, Bogerd J, Male R, Skaar KS, Schulz RW, Sorhus E, Wijgerde T, Taranger GL. Sex differentiation in Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua L.): morphological and gene expression studies. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2012;10:47. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-10-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Duffy TA, Picha ME, Won ET, Borski RJ, McElroy AE, Conover DO. Ontogenesis of gonadal aromatase gene expression in atlantic silverside (Menidia menidia) populations with genetic and temperature-dependent sex determination. J Exp Zool A Ecol Genet Physiol. 2010;313(7):421–431. doi: 10.1002/jez.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Blasco M, Fernandino JI, Guilgur LG, Strussmann CA, Somoza GM, Vizziano-Cantonnet D. Molecular characterization of cyp11a1 and cyp11b1 and their gene expression profile in pejerrey (Odontesthes bonariensis) during early gonadal development. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol. 2010;156(1):110–118. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meyer A, Schartl M. Gene and genome duplications in vertebrates: the one-to-four (−to-eight in fish) rule and the evolution of novel gene functions. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1999;11(6):699–704. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(99)00039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.D'Cotta H, Fostier A, Guiguen Y, Govoroun M, Baroiller J-F. Aromatase plays a key role during normal and temperature-induced sex differentiation of tilapia Oreochromis niloticus. Mol Reprod Dev. 2001;59(3):265–276. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Matson CK, Zarkower D. Sex and the singular DM domain: insights into sexual regulation, evolution and plasticity. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13(3):163–174. doi: 10.1038/nrg3161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gautier A, Le Gac F, Lareyre J-J. The gsdf gene locus harbors evolutionary conserved and clustered genes preferentially expressed in fish previtellogenic oocytes. Gene. 2011;472(1–2):7–17. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rondeau E, Messmer A, Sanderson D, Jantzen S, von Schalburg K, Minkley D, Leong J, Macdonald G, Davidsen A, Parker W, Mazzola R, Campell B, Koop B. Genomics of sablefish (Anoplopoma fimbria): expressed genes, mitochondrial phylogeny, linkage map and identification of a putative sex gene. BMC Genomics. 2013;14(1):452. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shibata Y, Paul-Prasanth B, Suzuki A, Usami T, Nakamoto M, Matsuda M, Nagahama Y. Expression of gonadal soma derived factor (GSDF) is spatially and temporally correlated with early testicular differentiation in medaka. Gene Expr Patterns. 2010;10(6):283–289. doi: 10.1016/j.gep.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Morrish B, Sinclair A. Vertebrate sex determination: many means to an end. Reproduction. 2002;124(4):447–457. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1240447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rodriguez-Mari A, Yan YL, Bremiller RA, Wilson C, Canestro C, Postlethwait JH. Characterization and expression pattern of zebrafish Anti-Mullerian hormone (Amh) relative to sox9a, sox9b, and cyp19a1a, during gonad development. Gene Expr Patterns. 2005;5(5):655–667. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mayor C, Brudno M, Schwartz JR, Poliakov A, Rubin EM, Frazer KA, Pachter LS, Dubchak I. VISTA: Visualizing global DNA sequence alignments of arbitrary length. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:1046. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.11.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Frazer KA, Pachter L, Poliakov A, Rubin EM, Dubchak I. VISTA: computational tools for comparative genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;1(32):W273–W279. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mohapatra S, Liu ZH, Zhou LY, Zhang YG, Wang DS. Molecular cloning of wt1a and wt1b and their possible involvement in fish sex determination and differentiation. Ind J Sci Technol. 2011;4(S8):85–86. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hale MC, Xu P, Scardina J, Wheeler PA, Thorgaard GH, Nichols KM. Differential gene expression in male and female rainbow trout embryos prior to the onset of gross morphological differentiation of the gonads. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:404. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Han F, Wang Z, Wu F, Liu Z, Huang B, Wang D. Characterization, phylogeny, alternative splicing and expression of Sox30 gene. BMC Mol Biol. 2010;11:98. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-11-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Baroiller JF, Guiguen Y, Fostier A. Endocrine and environmental aspects of sex differentiation in fish. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1999;55:910–931. doi: 10.1007/s000180050344. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Burmeister SS, Kailasanath V, Fernald RD. Social dominance regulates androgen and estrogen receptor gene expression. Horm Behav. 2007;51(1):164–170. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Böhne A, Sengstag T, Salzburger W. Comparative transcriptomics in East African cichlids reveals sex- and species-specific expression and new candidates for sex differentiation in fishes. Genome Biol Evol. 2014;6(9):2567–2585. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evu200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bezault E, Clota F, Derivaz M, Chevassus B, Baroiller J-F. Sex determination and temperature-induced sex differentiation in three natural populations of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) adapted to extreme temperature conditions. Aquaculture. 2007;272, Supplement(0):S3–S16. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2007.07.227. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jameson SA, Lin Y-T, Capel B. Testis development requires the repression of Wnt4 by Fgf signaling. Dev Biol. 2012;370(1):24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yu H, Pask A, Shaw G, Renfree M. Differential expression of WNT4 in testicular and ovarian development in a marsupial. BMC Dev Biol. 2006;6(1):44. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-6-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kim Y, Kobayashi A, Sekido R, DiNapoli L, Brennan J, Chaboissier M-C, Poulat F, Behringer RR, Lovell-Badge R, Capel B. Fgf9 and Wnt4 act as antagonistic signals to regulate mammalian sex determination. PLoS Biol. 2006;4(6):e187. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jeays-Ward K, Dandonneau M, Swain A. Wnt4 is required for proper male as well as female sexual development. Dev Biol. 2004;276(2):431–440. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Barrionuevo FJ, Burgos M, Scherer G, Jiménez R. Genes promoting and disturbing testis development. Histol Histopathol. 2012;27(11):1361–1383. doi: 10.14670/HH-27.1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Miyamoto Y, Taniguchi H, Hamel F, Silversides DW, Viger RS. A GATA4/WT1 cooperation regulates transcription of genes required for mammalian sex determination and differentiation. BMC Mol Biol. 2008;9:44. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-9-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Klüver N, Herpin A, Braasch I, Driessle J, Schartl M. Regulatory back-up circuit of medaka Wt1 co-orthologs ensures PGC maintenance. Dev Biol. 2009;325(1):179–188. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang R-S, Yeh S, Tzeng C-R, Chang C. Androgen receptor roles in spermatogenesis and fertility: Lessons from testicular cell-specific androgen receptor knockout mice. Endocr Rev. 2009;30(2):119–132. doi: 10.1210/er.2008-0025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Colombo M, Diepeveen ET, Muschick M, Santos ME, Indermaur A, Boileau N, Barluenga M, Salzburger W. The ecological and genetic basis of convergent thick-lipped phenotypes in cichlid fishes. Mol Ecol. 2013;22(3):670–684. doi: 10.1111/mec.12029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Laird PW, Zijderveld A, Linders K, Rudnicki MA, Jaenisch R, Berns A. Simplified mammalian DNA isolation procedure. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19(15):4293. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.15.4293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]