Abstract

Preclinical studies demonstrate that epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signals through both kinase-dependent and independent pathways and that combining a small-molecule EGFR inhibitor, EGFR antibody, and/or anti-angiogenic agent is synergistic. We conducted a dose-escalation, phase I study combining erlotinib, cetuximab, and bevacizumab. The subset of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer was analyzed for safety and antitumor activity. Forty-one patients with heavily pretreated metastatic colorectal cancer received treatment on a range of dose levels. The most common treatment-related grade ≥2 adverse events were rash (68%), hypomagnesemia (37%), and fatigue (15%). Thirty of 34 patients (88%) treated at the full FDA-approved doses of all three drugs tolerated treatment without drug-related dose-limiting effects. Eleven patients (27%) achieved stable disease (SD) ≥6 months and three (7%) achieved a partial response (PR) (total SD>6 months/PR= 14 (34%)). Of the 14 patients with SD≥6 months/PR, eight (57%) had received prior sequential bevacizumab and cetuximab, two (5%) had received bevacizumab and cetuximab concurrently, and four (29%) had received prior bevacizumab but not cetuximab or erlotinib (though three had received prior panitumumab). The combination of bevacizumab, cetuximab, and erlotinib was well tolerated and demonstrated antitumor activity in heavily pretreated patients with metastatic colorectal cancer.

Keywords: Erolotinib, Cetuximab, Bevacizumab, EGFR, VEGF

INTRODUCTION

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) plays an important role in tumorigenesis [1] and signals via downstream effectors [2]. EGFR protein is overexpressed in 35 to 49% of patients with colorectal cancer [3-5] with a higher percentage of EGFR overexpression in late stage colorectal tumors [6]. Cetuximab, a monoclonal antibody that binds to EGFR [7,8], is approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for K-Ras wild type metastatic colorectal cancer [9]. Erlotinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor of EGFR [10], is approved for locally advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer and locally advanced, unresectable, or metastatic pancreatic cancer, but is not currently FDA-approved for colorectal cancer.

Recently, Weihua et al. [11] discovered that EGFR can maintain cancer cell survival independent of its kinase activity. This kinase-independent pathway operates via increased glucose uptake due to stabilization of the SGLT1 glucose transporter, with a downstream effect of reduced autophagy [11]. Furthermore, preclinical studies revealed that combining antibodies and kinase inhibitors was synergistic in lung and head and neck cancer cell lines [12], as well as in lung xenografts [12], and an EGFR-dependent human xenograft model [13]. The combination of cetuximab and erlotinib synergistically inhibits growth of colon cancer cell lines, and has shown antitumor activity in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer [14].

Angiogenesis plays an important role in tumor development and metastasis [15], and is partly mediated by vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [16]. Bevacizumab is a recombinant anti-VEGF monoclonal antibody FDA-approved for treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer in combination with 5-fluorouracil-based chemotherapy [9]. Multiple studies combining chemotherapy and bevacizumab have demonstrated increased efficacy versus chemotherapy alone [17-19]. The addition of bevacizumab to chemotherapy regimens has increased overall survival [17], increased median progression-free survival [18], and improved response rate with longer duration of survival [19] in patients with colorectal cancer.

Anti-VEGF treatment used in conjunction with EGFR inhibitors has shown promise in preclinical and clinical studies. A xenograft study blocking VEGF and EGFR demonstrated synergistic antitumor activity [20], and mice intraperitoneally injected with human colon cancer cells showed improved antitumor activity in response to cetuximab and an anti-VEGF receptor 2 antibody [21]. Phase I and II clinical studies indicate increased efficacy with the combination of anti-VEGF and anti-EGFR therapy, with improved response rate, increased time to progression, and increased overall survival in patients who received cetuximab and bevacizumab [22] versus historical control groups of patients who received cetuximab [23], bevacizumab monotherapy [24], or cetuximab plus chemotherapy [25]. This activity of the combination of cetuximab and bevacizumab may be due to the fact that resistance to EGFR inhibitors is mediated, at least partly, by activating VEGF-dependent signaling [26,27].

Here, we report, for the first time, the results of administering dual EGFR inhibition (erlotinib plus cetuximab) together with an anti-angiogenic agent (bevacizumab) in patients with heavily-pretreated colorectal cancer.

RESULTS

Demographics

Forty-one patients with colorectal cancer were enrolled (Table 2). All patients had progressive disease at the time of enrollment. Most patients were heavily pretreated, with a median of five prior therapies (range, 2-12). Thirty-eight patients (93%) had previously received bevacizumab; 33 patients (80%), cetuximab; and one patient (2%) had received no prior study drugs.

Table 2. Patient Demographics.

| Characteristics (n=41) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| Median | 57 |

| Range | 32-76 |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Men | 19 (46%) |

| Women | 22 (54%) |

| Histologies, n (%) | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 41 (100%) |

| No. of prior systemic therapies | |

| Median | 5 |

| Range | 2-12 |

| Prior systemic treatment | |

| Prior bevacizumab | 38 (93%) |

| Prior bevacizumab (but no prior cetuximab or erlotinib) | 7 (17%) |

| Prior bevacizumab and cetuximab (sequential) | 27 (66%) |

| Prior bevacizumab and cetuximab (concurrent) | 4 (10%) |

| Prior cetuximab | 33 (80%) |

| Prior cetuximab (but no prior bevacizumab or erlotinib) | 2 (5%) |

| Prior erlotinib | 0 (0%) |

| Prior panitumumab | 5 (12%) |

| KRAS mutations, n (%) | |

| Positive | 2 (5%) |

| Negative | 31 (76%) |

| Unknown | 8 (20%) |

| EGFR mutations, n (%) | |

| Positive | 1 (2%) |

| Negative | 16 (39%) |

| Unknown | 24 (59%) |

| P53 mutations, n (%) | |

| Positive | 6 (15%) |

| Negative | 0 (0%) |

| Unknown | 35 (85%) |

| BRAF mutations, n (%) | |

| Positive | 1 (2%) |

| Negative | 27 (66%) |

| Unknown | 13 (32%) |

| PIK3CA mutations, n (%) | |

| Positive | 3 (7%) |

| Negative | 18 (44%) |

| Unknown | 20 (49%) |

| ECOG performance status, n (%) | |

| 0 | 5 (12%) |

| 1 | 34 (83%) |

| 2 | 2 (5%) |

Abbreviation: ECOG, Easter Cooperative Oncology Group; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor 1; P53, turmor protein 53.

Adverse Events

The most common treatment-related grade 2 or higher adverse events were rash (n=28, 68%), hypomagnesemia (n=18, 44%), fatigue (n=6, 14%), diarrhea (n=5, 12%), and hyperbiliruemia (n=4, 10%) (Table 1). Eight patients (20%) experienced no drug-related toxicity higher than grade 1. Seventeen patients (41%) required a dose reduction because of toxicity, including cetuximab in 13 patients for rash, two patients for diarrhea, one patient for hypomagnesemia, and one patient for diarrhea and transaminitis. Two patients (5%) withdrew due to toxicity, including grade 2 skin rash in cycle 1 (n=1) and grade 2 diarrhea and fatigue in cycle 1 (n=1). No deaths resulted from adverse events. The RP2D was level 8, which include the recommended FDA-approved full doses of each medication [28].

Table 1. Treatment-related Grade 2-4 adverse events.

| Dose Level | 1 n=2 | 2 n=1 | 3 n=0 | 4 n=1 | 5 n=0 | 6 n=0 | 7 n=3 | 8 n=34 | Total n=41 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bevacizumab Dose, mg/kg IV q2w | 2.5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 10 | ||

| Cetuximab Dose, mg/m2 IV weekly* | 100, 75 | 100, 75 | 200, 125 | 200, 125 | 200, 125 | 400, 250 | 400, 250 | 400, 250 | ||

| Erlotinib Dose, mg po daily | 50 | 50 | 50 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 150 | 150 | ||

| Skin rash | ||||||||||

| Grade 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 16 | 19 (46%) | |

| Grade 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 9 (22%) | |

| Hypomagnesemia | ||||||||||

| Grade 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 11 (27%) | |

| Grade 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 4 (10%) | |

| Grade 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 (7%) | |

| Fatigue | ||||||||||

| Grade 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 (12%) | |

| Grade 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (2%) | |

| Diarrhea | ||||||||||

| Grade 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 (7%) | |

| Grade 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 (5%) | |

| Hyperbilirubemia | ||||||||||

| Grade 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 (7%) | |

| Grade 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 (2%) | |

| Thrombocytopenia | ||||||||||

| Grade 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 (5%) | |

| Grade 3a | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (2%) | |

| Anorexia | ||||||||||

| Grade 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 (5%) | |

| Fever and chills | ||||||||||

| Grade 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 (5%) | |

| Hypertension | ||||||||||

| Grade 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 (5%) | |

| Chest pain | ||||||||||

| Grade 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 (2%) | |

| Chills | ||||||||||

| Grade 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (2%) | |

| Constipation | ||||||||||

| Grade 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (2%) | |

| Dyspnea | ||||||||||

| Grade 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 (2%) | |

| Fistula | ||||||||||

| Grade 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (2%) | |

| Hand and foot syndrome | ||||||||||

| Grade 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2%) | |

| Increased AST | ||||||||||

| Grade 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (2%) | |

| Increased AST/ALT | ||||||||||

| Grade 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 (2%) | |

| Infusion reaction | ||||||||||

| Grade 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 (2%) | |

| Neutropenia | ||||||||||

| Grade 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (2%) | |

| Proteinuria | ||||||||||

| Grade 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (2%) | |

| Pruritis | ||||||||||

| Grade 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (2%) |

Abbreviations: DLT, dose-limiting toxicity; IV, intravenous; po, orally

Recommended Phase II dose.31 This includes full approved doses of each drug.

Cetuximab dose shown as loading dose, maintenance dose.

Responses and time to treatment failure

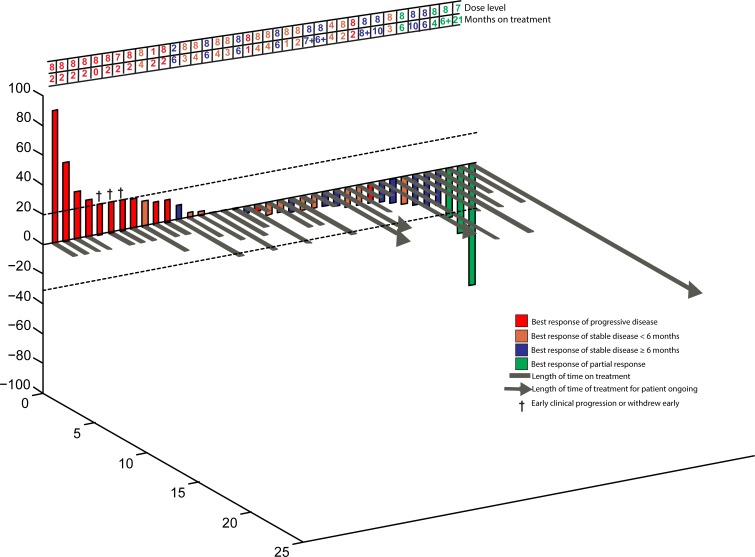

In total, SD≥6 months or PR was achieved in 14 patients (34%) (Figure 1). The overall confirmed response rate was 7% (PR). Eleven patients (27%) achieved stable disease (SD) lasting at least 6 months (duration was 6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6+, 7+, 8+, 10 and 10 months). Three patients (7%) achieved a PR and received treatment for 4, 6+, and 21 months (Table 3, Figure 2). Two patients withdrew before the first restaging assessment due to toxicity, and one patient withdrew early because of financial considerations. However, all patients were considered eligible for evaluation of response. Exploratory analysis of genomic aberrations was performed in selected patients who had tissue available (Table 4).

Figure 1. 3D-Waterfall.

Best response in 38 colorectal cancer patients treated. Patients with early clinical progression or new lesions before first restaging are indicated arbitrarily as +21% and are marked with a “†”. Three patients who withdrew early before restaging because of toxicity (n=2) or financial reasons (n=1) are not depicted in the figure. Patients with progressive disease are shown in red; patients who achieved stable disease are shown in orange, patients who achieved stable disease of at least six months are shown in blue; patients who achieved partial response are shown in green. The dose level and treatment duration (months) for each patient are shown in the table below. Patients still on treatment have a “+” after the number of months and are indicated with an arrow (>) on the grey bar for that patient.

Table 3. Patient characteristics for those who achieved stable disease of at least 6 months, partial response, or complete response.

| Case # | Best Response % | Treatment duration (months) | KRAS mutation | PTEN | TP53 mutation | EGFR mutation | HER2 Amplification | PIK3CA mutation | Prior bevacizumab | Prior cetuximab | Prior panitumumab | Brain metastases | Dose Level | Rash Grade |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 135 | −81 | 21 | NO | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | YES | NO | NO | NO | 7 | 2 |

| 336 | −44 | 6+ | NO | ND | YES | NO | NO | NO | YES | NO | NO | NO | 8 | 3 |

| 291 | −33 | 4 | NO | ND | ND | NO | ND | NO | YES | YES | NO | NO | 8 | 2 |

| 171 | −23 | 6 | NO | ND | YES | NO | ND | NO | YES | YES | NO | NO | 8 | 1 |

| 215 | −20 | 6 | NO | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | YESa | YESa | NO | NO | 8 | 2 |

| 245 | −16 | 10 | NO | PRESENT | ND | NO | ND | NO | YES | YES | NO | NO | 8 | 3 |

| 314 | −14 | 8+ | NO | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | YES | YES | NO | NO | 8 | 2 |

| 335 | −11 | 6+ | NO | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | YES | NO | YES | NO | 8 | 1 |

| 235 | −11 | 10 | NO | LOSS | YES | ND | ND | NO | YES | YES | NO | NO | 8 | 3 |

| 327 | −9 | 7+ | NO | ND | ND | NO | ND | ND | YES | NO | YES | NO | 8 | 1 |

| 277 | −9 | 6 | NO | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | YES | YES | NO | NO | 8 | 2 |

| 260 | −4 | 6 | NO | PRESENT | ND | ND | ND | YES | YES | YES | NO | NO | 8 | 2 |

| 221 | 0 | 6 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | YES | YES | NO | NO | 8 | 3 |

| 22 | 10 | 6 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | YES | YES | NO | NO | 2 | 0 |

Abbreviations: EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor 1; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; ND, not done; PIK3CA, phosphoinositide-3-kinase, catalytic, alpha polypeptide.

indicates patients who received prior study drugs concurrently.

indicates ongoing therapy

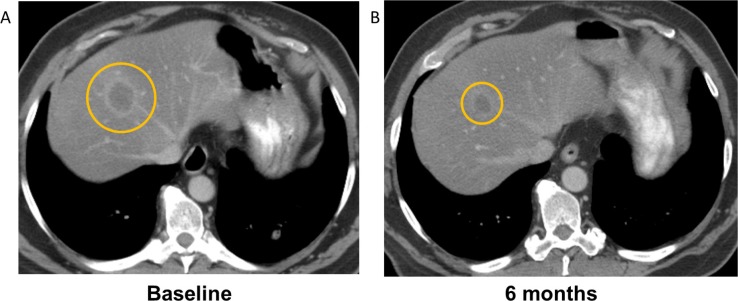

Figure 2. Computerized tomography (CT) demonstrating response to treatment with combination cetuximab, erlotinib, and bevacizumab in a patient with KRAS wild-type colorectal cancer who had received prior cetuximab and bevacizumab.

A decrease in tumor size of 45% by RECIST was observed, and the patient received treatment for 6 months. Panel A demonstrates a liver metastasis at baseline, and Panel B demonstrates the tumor after 6 months of treatment.

Table 4. Gene mutation status and response.

| Gene | Proportion of patients with mutation out of number tested (% of patients positive) | Mutations identified | Number of patients who achieved SD>6 months/PR (by mutation status) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutant | Wild type | |||

| EGFR | 1 of 17 (6%) | G719D (n=1) | EGFR mutant: 0/1 | EGFR wt: 5/16 |

| BRAF | 1 of 28 (4%) | V600E (n=1) | BRAF mutant: 0/1 | BRAF wt: 8/27 |

| KRAS | 2 of 33 (6%) | G12V (n=1)G12D (n=1) | KRAS mutant 0/2 | KRAS wt: 13/31 |

| P53 | 6 of 6 (100%) | R175H (n=3)T125K (n=1)S227fs*1 (n=1)R248W (n=1) | P53 mutant: 3/6 | N/A |

| PIK3CA | 3 of 21 (14%) | R1023Q (n=1)E545K (n=1)Q546R (n=1) | PIK3CA mutant: 1/3 | PIK3C wt: 6 of 18 |

| PTEN | 1 of 6 (17%) had PTEN loss 2 of 6 (33%) had weakly present PTEN 3 of 6 (50%) had PTEN present |

N/A | 1 of 1 (PTEN loss) | 2 of 3 (PTEN present) |

| FBXW7 | 1 of 1(100%) | R222 (n=1) | 0 of 1 | N/A |

| APC | 1 of 1(100%) | T820fs*7 and P1439fd*34 (n=1) | 0 of 1 | N/A |

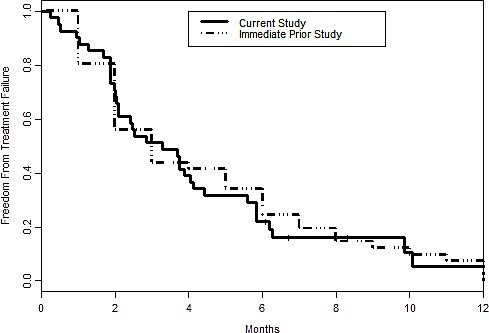

Median time to treatment failure for the current treatment is 3.3 months with 95% CI = (2.1, 4.4), while for the immediately prior standard treatment, the median is 3.0 (2.0, 6.0). (p=.71) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Kaplan-Meier curve for time to treatment failure for the current study versus the immediately prior standard therapy.

Prior EGFR inhibitor or VEGF Inhibitor Therapy and Response

Of 41 patients on study, a total of 38 patients (93%) had received prior bevacizumab, and a total of 33 patients (80%) had received prior cetuximab (Table 2). Thirty-one patients (76%) had received prior bevacizumab and prior cetuximab (27 sequentially, 4 concurrently), seven patients (17%) had received prior bevacizumab and no other study drugs, and two patients (5%) had received prior cetuximab and no additional study drugs. No patients had received prior erlotinib. Four patients had previously received panitumumab, a monoclonal antibody that binds to EGFR and inhibits epidermal growth factor autocrine signaling.

Prior bevacizumab and cetuximab, even if given concurrently, did not preclude SD≥6 months/PR. Four of the seven patients (56%) who received prior bevacizumab and no other prior study drugs achieved SD≥6 months/ PR; three of these four patients had also received prior panitumumab. Of the 38 patients who had received prior bevacizumab, 14 (37%) achieved SD≥6 months/PR; of the 33 patients that received prior cetuximab, 10 (30%) achieved SD≥6 months/PR; of the 31 patients who had received prior cetuximab and bevacizumab, 10 (32%) achieved SD≥6 months/PR. The latter included four patients who had received prior concurrent bevacizumab and cetuximab, two of whom achieved SD≥6 months/PR. Of the 14 patients with SD≥6 months/PR, eight (57%) had received prior sequential bevacizumab and cetuximab, two (5%) had received bevacizumab and cetuximab concurrently, and four (29%) had received prior bevacizumab but not cetuximab (though three had received prior panitumumab (Table 3 and Figure 1). Patient 135, who had received prior panitumumab and had also previously received bevacizumab, achieved a partial response and was on study for 21 months (Table 3).

Dosing and Response

Of 37 patients on dose levels 7 or 8, thirteen (35%) achieved SD≥6 months/PR. Of the four patients treated at dose levels 1-6, one patient (25%) achieved SD≥6 months/PR (Table 1 and Figure 1). There was no obvious dose-response correlation, although the number of patients at lower dose levels was small.

Toxicity and Response

Rash was the most frequently observed toxicity in patients (Table 1). Patients with grade 2 or higher rash were not significantly more likely to attain SD≥6 months/PR (two-tailed chi squared, p=0.76). Nineteen patients experienced grade 2 rash, of whom six (31%) achieved SD≥6 months/PR. Four of nine patients (44%) with grade 3 rash achieved SD≥6 months/PR (Table 3). Of 13 patients with grade 1 or no rash, four (31%) achieved SD≥6 months/PR.

DISCUSSION

We report the results of the cohort of patients with colorectal cancer treated on a phase I dose-escalation trial of combination cetuximab, erlotinib, and bevacizumab. The rationale for this combination was: (1) preclinical and clinical studies that suggested increased activity when anti-VEGF therapy was combined with EGFR inhibitors [20,21], (2) preclinical studies indicating that EGFR signals through both kinase-dependent and -independent pathways [11], and (3) clinical trials demonstrating increased overall survival in patients treated with cetuximab and bevacizumab [22].

This combination of drugs was well-tolerated. The RP2D was determined to be the full FDA-approved doses for all three drugs [28], and 31 of the 34 patients (91%) treated at the RP2D tolerated treatment without drug-related dose-limiting effects.

This regimen demonstrated antitumor activity in patients with colorectal cancer, including 14 patients (34%) who had a best overall response of SD≥6 months (n=11) or PR (n=3). SD≥6 months/PR was observed even in patients who had received prior bevacizumab and/or cetuximab or treated at a lower dose level.

Previous phase II/III clinical studies combining cetuximab and bevacizumab with cytotoxic chemotherapy in patients with colorectal cancer resulted in disappointing results [29-32]. One notable difference is that our current study included erlotinib dosing up to 150 mg daily, in contrast to 100 mg in prior studies [14]. It is conceivable that, in this context, the chemotherapy component of the above regimen may be detrimental, whereas regimens that combine anti-EGFR and anti-VEGF agents without cytotoxic chemotherapy deserve further investigation. Indeed, studies in pancreatic adenocarcinoma [33] and squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck [34] that use a combination of cetuximab and bevacizumab show promising results.

A prior preclinical study combining erlotinib and cetuximab demonstrated synergistic antitumor activity in colorectal cancer [14], and a related phase II clinical trial of this combination achieved an overall response rate of 31% [14], which is similar to the rate of SD≥6 months/PR observed in our study. Importantly, the phase II study of erlotinib and cetuximab did not report the number of prior systemic therapies, whereas our study included patients who were heavily pretreated (median of five prior systemic therapies).

Remarkably, patients in our study who previously had failed bevacizumab and/or cetuximab were able to acheive SD≥6 months/PR. Recent studies suggest that combining EGFR kinase inhibitors and anti-EGFR antibodies may be more effective than either alone, perhaps because EGFR is able to maintain cancer cell survival independent of its kinase activity [11-14]. The clinical data presented here also support combining kinase inhibitors and antibodies.

Exploratory analysis of molecular aberrations was performed. Of the 14 patients who achieved SD≥6 months/PR in our study, four had mutations present (PIK3CA E545K (n=1), TP53 R175H and PTEN loss (n=1), TP53 R175H (n=1), TP53 R248W (n=1). This analysis is limited however by the fact that only a small number of mutations were evaluated in individual patients.

Previous studies demonstrated a correlation between rash and response to EGFR inhibitors [35,36]. However, in our study we did not observe a trend of higher grade rash in patients with SD≥6 months/PR (p=0.76). Larger studies could have more definitive conclusions in this regard.

There are several limitations to this study. First, molecular correlates could only be obtained in a small subset of patients, precluding a robust analysis. Second, these patients had a median of five prior therapies in the metastatic setting, perhaps attenuating their ability to respond. Third, determination of time to treatment failure of prior therapy was obtained from chart review, rather than prospectively.

In conclusion, the results presented here demonstrate that dual inhibition of EGFR with erlotinib and cetuximab, combined with the VEGF antibody bevacizumab, is well-tolerated, allowing full doses of all three drugs in patients with colorectal cancer. The most common side effect is rash. SD≥6 months/PR was achieved in 34% of this heavily pretreated patient population, including patients treated with prior bevacizumab and/or cetuximab. These findings merit further investigation in a larger study of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer.

METHODS

Study Design

This report is a subset analysis of a larger phase I study of combination cetuximab, erlotinib, and bevacizumab. The study was conducted at The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC) per Institutional Review Board guidelines. The colorectal cancer cohort reported herein included all patients with colorectal cancer who started therapy between 12/10/2007 and 5/7/2012 as part of a dose-escalation study conducted in patients with advanced cancer. The dose escalation portion of the study determined the recommended phase II dose (RP2D) to be bevacizumab 10 mg/kg IV every two weeks; cetuximab loading 400 mg/m2, maintenance 250 mg/m2 IV weekly; and erlotinib 150 mg PO daily on a 28 cycle [28]. Patients were treated at variable dose levels, depending on the time of study entry (Table 1).

Patients

Patients had metastatic or advanced colorectal cancer not amendable to standard therapy, an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status 0-2 [37], and adequate hematologic, hepatic, and renal function. Exclusion criteria included hemoptysis, unexplained bleeding, significant cardiovascular disease, intercurrent uncontrolled illness, significant gastrointestinal bleeding within 28 days, hemorrhagic brain metastases, prior abdominal surgery within 30 days, pregnancy, and a history of hypersensitivity to bevacizumab, cetuximab, and/or erlotinib. Treatment with prior cytotoxic therapies must have ended at least three weeks prior to enrollment, and biologic therapy must have either ended at least two weeks or five drug half-lives prior to enrollment, whichever was shorter. Patients may have received an unlimited number of prior therapies, including prior anti-EGFR and anti-angiogenic agents.

Safety

Clinically significant adverse events were assessed according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI CTCAE), version 3.0. History, physical exam, hematology, blood chemistry, and urinalysis were performed at baseline and regular intervals while receiving treatment.

Evaluation of Efficacy

Treatment efficacy was evaluated by diagnostic imaging per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) 1.0 [38]. Radiologic assessments were conducted at baseline and about every 8 weeks thereafter.

Molecular Testing

EGFR, KRAS, PIK3CA, p53, and BRAF mutation analysis, as well as PTEN expression by immunohistochemistry, were performed in the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)-approved MDACC laboratory for patients with available archived tissue (supplementary methods).

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were descriptive and exploratory. Correlational statistics were determined by Spearman's correlation and dichotomous variables were evaluated with chi-square or Fisher's exact test. We estimated the time to treatment failure distribution using the Kaplan-Meier product limit method, and estimation of 95% confidence interval for the mean was calculated using conventional methods (mean +/− 2*SEM where SEM = standard error of the mean). Time to treatment failure was defined as the duration of treatment received until a patient developed progressive disease or withdrawal from study because of toxicity or any other reason.

SUPPLEMENTARY METHODS

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a K12 Paul Calabresi Career Development Award for Clinical Oncology, CA088084 from the National Institutes of Health and the National Cancer Institute. We thank the patients and their families. We also thank Adrienne Howard for regulatory protocol assistance.

Footnotes

Financial support:

This research was supported by a K12 Paul Calabresi Career Development Award for Clinical Oncology, CA088084 from the National Institutes of Health and the National Cancer Institute.

Conflict of Interest:

All authors with exception of Razelle Kurzrock have no competing interests that might be perceived to influence the content of this article. Dr. Kurzrock received research support from Genentech.

REFERENCES

- 1.Voldborg BR, Damstrup L, Spang-Thomsen M, Skovgaard Poulsen H. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and EGFR mutations, function and possible role in clinical trials. Ann Oncol. 1997;8:1197–206. doi: 10.1023/a:1008209720526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Normanno N, De Luca A, Bianco C, Strizzi L, Mancino M, Maiello MR, Carotenuto A, De Feo G, Caponigro F, Salomon DS. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling in cancer. Gene. 2006;366:2–16. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldstein NS, Armin M. Epidermal growth factor receptor immunohistochemical reactivity in patients with American Joint Committee on Cancer Stage IV colon adenocarcinoma: implications for a standardized scoring system. Cancer. 2001;92:1331–46. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010901)92:5<1331::aid-cncr1455>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKay JA, Murray LJ, Curran S, Ross VG, Clark C, Murray GI, Cassidy J, McLeod HL. Evaluation of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) in colorectal tumours and lymph node metastases. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38:2258–64. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(02)00234-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Resnick MB, Routhier J, Konkin T, Sabo E, Pricolo VE. Epidermal growth factor receptor, c-MET, beta-catenin, and p53 expression as prognostic indicators in stage II colon cancer: a tissue microarray study. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:3069–75. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-03-0462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spano JP, Lagorce C, Atlan D, Milano G, Domont J, Benamouzig R, Attar A, Benichou J, Martin A, Morere J-F, Raphael M, Panault-Llorca F, Breau J-L, et al. Impact of EGFR expression on colorectal cancer patient prognosis and survival. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:102–8. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graham J, Muhsin M, Kirkpatrick P. Cetuximab. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:549–50. doi: 10.1038/nrd1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Papa A, Rossi L, Lo Russo G, Giordani E, Spinelli GP, Zullo A, Petrozza V, Tomao S. Emerging role of cetuximab in the treatment of colorectal cancer. Recent Pat Anticancer Drug Discov. 2012;7:233–47. doi: 10.2174/157489212799972882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.US Food and Drug Administration Drugs@FDA: FDA approved drug products. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/SCRIPTS/CDER/DRUGSATFDA/INDEX.CFM (8 Aug 2012, date last accessed)

- 10.Kim TE, Murren JR. Erlotinib OSI/Roche/Genentech. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2002;3:1385–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weihua Z, Tsan R, Huang WC, Wu Q, Chiu C-H, Fidler IJ, Hung M-C. Survival of cancer cells is maintained by EGFR independent of its kinase activity. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:385–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang S, Armstrong EA, Benavente S, Chinnaiyan P, Harari PM. Dual-agent molecular targeting of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR): combining anti-EGFR antibody with tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5355–62. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matar P, Rojo F, Cassia R, Moreno-Bueno G, Di Cosimo S, Tabernero J, Guzman M, Rodriguez S, Arribas J, Palacios J, Baselga J. Combined epidermal growth factor receptor targeting with the tyrosine kinase inhibitor gefitinib (ZD1839) and the monoclonal antibody cetuximab (IMC-C225): superiority over single-agent receptor targeting. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:6487–501. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weickhardt AJ, Price TJ, Chong G, Gebski V, Pavlakis N, Johns TG, Azad A, Skrinos E, Fluck K, Dobrovic A, Salemi R, Scott AM, Mariadason JM. Dual targeting of the epidermal growth factor receptor using the combination of cetuximab and erlotinib: preclinical evaluation and results of the phase II DUX study in chemotherapy-refractory, advanced colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1505–12. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.6599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holash J, Maisonpierre PC, Compton D, Boland P, Alexander CR, Zagzag D, Yancopoulos GD, Wiegand SJ. Vessel cooption, regression, and growth in tumors mediated by angiopoietins and VEGF. Science. 1999;284:1994–8. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5422.1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferrara N, Kerbel RS. Angiogenesis as a therapeutic target. Nature. 2005;438:967–74. doi: 10.1038/nature04483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grothey A, Sugrue MM, Purdie DM, Dong W, Sargent D, Hedrick E, Kozloff M. Bevacizumab beyond first progression is associated with prolonged overall survival in metastatic colorectal cancer: results from a large observational cohort study (BRiTE) J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5326–34. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.3212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W, Cartwright T, Hainsworth J, Heim W, Berlin J, Baron A, Griffing S, Holmgren E, Ferrara N, Fyfe G, Rogers B, et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2335–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kabbinavar F, Hurwitz HI, Fehrenbacher L, Meropol NJ, Novotny WF, Lieberman G, Griffing S, Bergsland E. Phase, II, randomized trial comparing bevacizumab plus fluorouracil (FU)/leucovorin (LV) with FU/LV alone in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:60–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ciardiello F, Bianco R, Damiano V, Fontanini G, Caputo Rosa, Pomatico G, De Placido S, Bianco R, Mendelsohn J, Tortora G. Antiangiogenic and antitumor activity of anti-epidermal growth factor receptor C225 monoclonal antibody in combination with vascular endothelial growth factor antisense oligonucleotide in human GEO colon cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:3739–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shaheen RM, Ahmad SA, Liu W, Reinmuth N, Jung YD, Tseng WW, Drazan KE, Bucana CD, Hicklin DJ, Ellis LM. Inhibited growth of colon cancer carcinomatosis by antibodies to vascular endothelial and epidermal growth factor receptors. Br J Cancer. 2001;85:584–9. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saltz LB, Lenz HJ, Kindler HL, Hochster HS, Wadler S, Hoff PM, Kemeny NE, Hollywood EM, Gonen M, Quinones M, Morse M, Chen HX. Randomized phase II trial of cetuximab, bevacizumab, and irinotecan compared with cetuximab and bevacizumab alone in irinotecan-refractory colorectal cancer: the BOND-2 study. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4557–61. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.0949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cunningham D, Humblet Y, Siena S, Khayat D, Bleiberg H, Santoro A, Bets D, Mueser M, Harstrick A, Verslype C, Chau I, Van Cutsem E. Cetuximab monotherapy and cetuximab plus irinotecan in irinotecan-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:337–45. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giantonio BJ, Catalano PJ, Meropol NJ, O'Dwyer PJ, Mitchell EP, Alberts SR, Schwartz MA, Benson AB. Bevacizumab in combination with oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin (FOLFOX4) for previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer: results from the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study E3200. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1539–44. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.6305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sobrero AF, Maurel J, Fehrenbacher L, Scheithauer W, Abubakr YA, Lutz MP, Vega-Villegas ME, Eng C, Steinhauer EU, Prausova J, Lenz H-J, Borg C, Middleton G, et al. EPIC: phase III trial of cetuximab plus irinotecan after fluoropyrimidine and oxaliplatin failure in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2311–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lichtenberger BM, Tan PK, Niederleithner H, Ferrara N, Petzelbauer P, Sibilia M. Autocrine VEGF signaling synergizes with EGFR in tumor cells to promote epithelial cancer development. Cell. 2010;140:268–79. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tortora G, Ciardiello F, Gasparini G. Combined targeting of EGFR-dependent and VEGF-dependent pathways: rationale, preclinical studies and clinical applications. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2008;5:521–30. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Falchook GS, Wheler JJ, Naing, Hong DS, Moulder SL, Piha-Paul SA, Ng CS, Jackson E, Kurzrock R. A phase I study of bevacizumab in combination with sunitinib, sorafenib, and erlotinib plus cetuximab, and trastuzumab plus lapatin. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28 abstr 2512. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dotan E, Meropol NJ, Burtness B, Denlinger CS, Lee J, Mintzer D, Zhu F, Ruth K, Tuttle H, Sylvester J, Cohen SJ. A Phase II Study of Capecitabine, Oxaliplatin, and Cetuximab with or Without Bevacizumab as Frontline Therapy for Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. A Fox Chase Extramural Research Study. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s12029-012-9368-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hecht JR, Mitchell E, Chidiac T, Scroggin C, Hagenstad C, Spigel D, Marshall J, Cohn A, McCollum D, Stella P, Deeter R, Shahin S, Amado RG. A randomized phase IIIB trial of chemotherapy, bevacizumab, and panitumumab compared with chemotherapy and bevacizumab alone for metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:672–80. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.8135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saltz L, Badarinath S, Dakhil S, Bienvenu B, Harker WG, Birchfield G, Tokaz LK, Barrera D, Conkling PR, O'Rourke MA, Richards DA, Reidy D, Solit D, et al. Phase III trial of cetuximab, bevacizumab, and 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin vs. FOLFOX-bevacizumab in colorectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2012;11:101–11. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siu LL, Shapiro JD, Jonker DJ, Karapetis CS, Zalchberg JR, Simes J, Couture F, Moore MJ, Price TJ, Siddiqui J, Nott LM, Charpentier D, Liauw W, et al. Phase III randomized, placebo-controlled study of cetuximab plus brivanib alaninate versus cetuximab plus placebo in patients with metastatic, chemotherapy-refractory, wild-type K-RAS colorectal carcinoma: the NCIC Clinical Trials Group and AGITG, CO.20 Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2477–2484. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.0543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ko AH, Youssoufian H, Gurtler J, Dicke K, Kayaleh O, Lenz H-J, Keaton M, Katz T, Ballal S, Rowinsky EK. A phase II randomized study of cetuximab and bevacizumab alone or in combination with gemcitabine as first-line therapy for metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Invest New Drugs. 2012;30:1597–606. doi: 10.1007/s10637-011-9691-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Argris A, Kotsakis AP, Hoang T, Worden FP, Savvides P, Gibson MK, Gyanchandani R, Blumenschein GR, Chen HX, Grandis Jr, Harari PM, Kies MS, Kim S. Cetuximab and bevacizumab: preclinical data and phase II trial in recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:220–5. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dobi E, Monnien F, Kim S, Ivanaj A, N'Guyen T, Demarchi M, Adotevi O, Thierry-Vuillemin A, Jary M, Kantelip B, Pivot X, Godet Y, Valmary Degano S, et al. Impact of STAT3 Phosphorylation on the Clinical Effectiveness of Anti-EGFR-Based Therapy in Patients With Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chiorean EG, Ramasubbaiah R, Yu M, Picus J, Bufill JA, Tong Y, Coleman N, Johnston EL, Currie C, Loehrer PJ. Phase II trial of erlotinib and docetaxel in advanced and refractory hepatocellular and biliary cancers: Hoosier Oncology Group GI06-101. Oncologist. 17:13, 201. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, Horton J, Davis TE, McFadden ET, Carbone PP. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5:649–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, Wanders J, Kaplan RS, Rubinstein L, Verweij J, Van Glabbeke M, van Oosterom AT, Christian MC, Gwyther SG. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205–16. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.