Abstract

The feasibility of sequence analysis of the 16S-23S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) intergenic spacer (ITS) for the identification of clinically relevant viridans group streptococci (VS) was evaluated. The ITS regions of 29 reference strains (11 species) of VS were amplified by PCR and sequenced. These 11 species were Streptococcus anginosus, S. constellatus, S. gordonii, S. intermedius, S. mitis, S. mutans, S. oralis, S. parasanguinis, S. salivarius, S. sanguinis, and S. uberis. The ITS lengths (246 to 391 bp) and sequences were highly conserved among strains within a species. The intraspecies similarity scores for the ITS sequences ranged from 0.98 to 1.0, except for the score for S. gordonii strains. The interspecies similarity scores for the ITS sequences varied from 0.31 to 0.93. Phylogenetic analysis of the ITS regions revealed that evolution of the regions of some species of VS is not parallel to that of the 16S rRNA genes. One hundred six clinical isolates of VS were identified by the Rapid ID 32 STREP system (bioMérieux Vitek, Marcy l'Etoile, France) and by ITS sequencing, and the level of disagreement between the two methods was 18% (19 isolates). Most isolates producing discrepant results could be unambiguously assigned to a specific species by their ITS sequences. The accuracy of using ITS sequencing for identification of VS was verified by 16S rDNA sequencing for all strains except strains of S. oralis and S. mitis, which were difficult to differentiate by their 16S rDNA sequences. In conclusion, identification of species of VS by ITS sequencing is reliable and could be used as an alternative accurate method for identification of VS.

Viridans group streptococci (VS) are the most common etiologic agents of subacute infective endocarditis and are capable of causing a variety of pyogenic infections (9). VS can be divided into five major groups on the basis of the 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) sequences: (i) the mutans group, (ii) the salivarius group, (iii) the anginosus group (also called the milleri group), (iv) the sanguinis group, and (v) the mitis group (9).

VS can be isolated as part of the normal flora of the respiratory, genital, and alimentary tracts. However, species of VS are playing an increasing role in infections among immunocompromised patients (33). The clinical significance of VS may differ between species, and sometimes it is important to identify the individual species associated with diseases (18). Jacobs et al. (19) studied 104 isolates of VS recovered from blood cultures and found that Streptococcus oralis and S. mitis were the two species most frequently isolated from patients in the hematology unit, whereas species of the anginosus group were the most common species isolated from the general hospital population. Chang et al. (7) found that VS accounted for 9% of all cases of culture-proven bacterial meningitis in adults, and more than 80% of VS causing meningitis were species of the anginosus group. These data provided further insight into the search for the link between species and the diseases that they can cause.

The antimicrobial susceptibilities of VS isolated from patients with significant infections in Taiwan revealed that high-level penicillin resistance (MICs ≥ 4 μg/ml) was frequently found in isolates of S. oralis (35%) and S. mitis (20%). Macrolide resistance also occurred most frequently in S. oralis isolates (55%) but in none of S. mutans isolates (35). However, Tracy et al. (38) found that there were no differences in antimicrobial susceptibilities among species (S. anginosus, S. constellatus, and S. intermedius) of the anginosus group. Those investigators expressed the opinion that it was unnecessary to identify VS to the species level and that identification of an infecting organism as a member of the anginosus group might be sufficient for patient management, but whether the same can be said for other VS remains to be established (38).

Nearly 40 conventional tests have been used to differentiate species of VS, but phenotypic tests do not allow an unequivocal identification of some species of this heterogeneous group of bacteria (1, 10, 23). This is because variability in a common phenotypic trait among strains is common (4, 17, 22). Species of S. mutans strains and strains of the anginosus and mitis groups are the most problematic to differentiate (11, 18, 32).

Several molecular methods have been developed for the identification of VS to the species level (5, 11, 12, 18, 21, 29, 36). The targets include the rRNA genes (6, 8, 18, 20, 30), the tRNA gene intergenic spacer (ITS) (12), and the genes encoding d-alanine-d-alanine ligase (11), manganese-dependent superoxide dismutase (sodAint) (26), and heat shock proteins (groESL) (34). A variety of techniques, including DNA hybridization (18, 21, 30, 32), PCR product length polymorphism analysis (12), arbitrarily primed PCR (29), and comparative DNA sequence analysis, have been used for molecular diagnosis (6, 8, 26, 36). Compared with the lengths of 16S rDNA (≈1.5 kb) (27) and groESL (≈2 kb) (36), the ITS lengths of VS are relatively short (<400 bp). In addition, S. mitis and S. oralis cannot be differentiated by analyzing the groESL (36) and sodAint genes (26), since intraspecies sequence variations are higher than interspecies variations.

The ITS separating the 16S and 23S rDNAs has been suggested to be a good candidate for use in molecular assays for bacterial species identification (3, 39) and strain typing (15). Sequences of the ITS regions have been found to have low levels of intraspecies variation and high levels of interspecies divergence (40). The aim of this study was to investigate the feasibility of using the ITS sequences to identify 11 clinically relevant species of VS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains. Twenty-nine type or reference strains of VS, including S. anginosus, S. constellatus, S. gordonii, S. intermedius, S. mitis, S. mutans, S. oralis, S. parasanguinis, S. salivarius, S. sanguinis, and S. uberis, were used in this study (Table 1). Most of these strains were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, Va.). S. intermedius NCDO 2227 was obtained from the National Collection of Food Bacteria, Reading, United Kingdom. In addition, type strains of S. agalactiae (ATCC 13813), S. pneumoniae (ATCC 33400), S. pyogenes (ATCC 14289), and Enterococcus faecalis (ATCC 19433) and two reference strains of S. pneumoniae (ATCC 27336 and ATCC 49169) were also used for comparison of their ITS sequences with those of VS. A total of 106 clinical isolates of VS were obtained from National Taiwan University Hospital (Taipei, Taiwan) and National Cheng Kung University Medical Center (Tainan, Taiwan). Most of the clinical isolates were recovered from blood cultures and deep abscesses (e.g., brain abscesses) and were phenotypically identified with the Rapid ID 32 STREP system (bioMérieux Vitek, Marcy l'Etoile, France).

TABLE 1.

Intraspecies similarity scores for the 16S-23S rDNA ITSs of different species of VS

| Species | Strain no.a | Size of ITS (bp) | Similarity scoreb | GenBank accession no.c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. anginosus | ATCC 33397d | 391 | AY347541 | |

| ATCC 700231 | 390 | 0.99 | AY351328 | |

| NCTC 10713e | 391 | 0.99 | L36931 | |

| S. constellatus | ATCC 27513d | 391 | AY347545 | |

| ATCC 27823 | 390 | 0.99 | AY347546 | |

| NCDO 2226e | 391 | 0.99 | L36933 | |

| S. gordonii | ATCC 10558d | 246 | AY353081 | |

| ATCC 10558e | 246 | 1.00 | AB051019 | |

| ATCC 49818 | 248 | 0.94 | AY351328 | |

| ATCC 35105 | 248 | 0.94 | AY351326 | |

| S. intermedius | ATCC 27335d | 370 | AY347549 | |

| NCDO 2227 | 370 | 1.00 | L36934 | |

| S. mitis | ATCC 49456d | 248 | AY347550 | |

| SK24e | 249 | 0.99 | AB051020 | |

| S. mutans | ATCC 31377d | 388 | AY351323 | |

| ATCC 31383 | 387 | 0.98 | AY351324 | |

| GS5f | 387 | 0.99 | AY351312 | |

| MT4251e | 388 | 0.99 | AB050990 | |

| MT4245e | 388 | 0.99 | AB050988 | |

| MT8148e | 388 | 0.99 | AB050989 | |

| S. oralis | ATCC 35037d | 246 | AY347551 | |

| ATCC 55229 | 246 | 0.99 | AY347553 | |

| ATCC 700233 | 246 | 0.99 | AY347554 | |

| ATCC 700234 | 246 | 0.99 | AY347555 | |

| ATCC 9811 | 246 | 0.99 | AY347568 | |

| ATCC 10557e | 246 | 0.99 | AB051018 | |

| S. parasanguinis | ATCC 15912d | 249 | AY351320 | |

| ATCC 15909 | 249 | 0.99 | AY351319 | |

| S. salivarius | ATCC 13419d | 273 | AY347562 | |

| ATCC 7073 | 273 | 0.99 | AY347561 | |

| ATCC 25975 | 273 | 1.00 | AY347564 | |

| ATCC 15910 | 273 | 0.99 | AY347563 | |

| DSM 20560e | 273 | 0.99 | AJ439458 | |

| NCTC 8618e | 273 | 0.98 | AB051016 | |

| S. sanguinis | ATCC 10556d | 264 | AY347565 | |

| UASsB22e | 264 | 1.00 | AF271353 | |

| UASsB25e | 264 | 1.00 | AF271355 | |

| UASsB29e | 264 | 0.99 | AF271351 | |

| UASsB30e | 264 | 1.00 | AF271354 | |

| UASsB47e | 264 | 0.99 | AF271352 | |

| S. uberis | ATCC 13386d | 340 | AY347566 | |

| ATCC 700407 | 338 | 0.97 | AY347567 | |

| ATCC 19436 | 340 | 0.99 | AY347538 | |

| NCDO 2038e | 338 | 0.99 | AF255657 | |

| ATCC 27958e | 340 | 0.99 | U39768 |

DSM, Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen, Braunschweig, Germany; NCDO, National Collection of Food Bacteria, Reading, United Kingdom; NCTC, National Collection of Type Cultures, Public Health Laboratory, London, United Kingdom.

The type strains were used as the basis for calculation of similarity scores.

The ITS sequences (GenBank accession numbers) of S. agalactiae ATCC 13813 (AY347539), S. pneumoniae ATCC 33400 (AY347557), ATCC 27336 (AY347556), ATCC 49169 (AY347558), S. pyogenes ATCC 14289 (AY347560), and E. faecalis ATCC 19433 (AY351321) were also submitted to GenBank.

Type strain.

Strains for which ITS sequences are available in the GenBank database.

Clinical isolate.

DNA preparation.

The boiling method described by Millar et al. (25) was used to extract DNA from the bacteria. Briefly, one colony from pure cultures was suspended in 20 μl of sterilized water and heated at 100°C for 15 min in a heating block. After centrifugation in a microcentrifuge (6,000 × g for 3 min), the supernatant containing bacterial DNA was stored at −20°C for further use.

Amplification of ITS regions and nucleotide sequence determination.

The bacterium-specific universal primers 13BF (5′-GTGAA TACGT TCCCG GGCCT-3′) (27) and 6R (5′-GGGTT YCCCC RTTCR GAAAT-3′ ) (15) (where Y is C or T and R is A or G) were used to amplify a DNA fragment that encompassed a small portion of the 16S rDNA region, the ITS, and a small portion of the 23S rDNA region. The 5′ end of primer 13BF is located at position 1371 of the 16S rDNA, and the 5′ end of primer 6R is located at position 108 downstream of the 5′ end of the 23S rDNA (Escherichia coli numbering). PCR was performed with 5 μl (1 to 5 ng) of template DNA in a total reaction volume of 50 μl consisting of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.8 mM deoxyribonucleoside triphosphates (0.2 mM each), 0.1 μM (each) primer, 1 U of Taq DNA polymerase, and 50 μl of a mineral oil overlay. The PCR program consisted of 8 cycles of denaturation (94°C for 2 min), annealing (55°C for 1 min), and extension (72°C for 1 min), followed by 30 cycles of denaturation (94°C for 1 min), annealing (60°C for 1 min), and extension (72°C for 1 min) and a final extension step at 72°C for 3 min. An OmniGen thermal cycler (Hybaid Limited, Winsford, United Kingdom) was used for PCR.

The PCR products were purified with a PCR-M Clean Up kit (Viogene, Taipei, Taiwan) and were sequenced on a model 377 sequencing system (Applied Biosystems, Taipei, Taiwan) with a BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing kit (version 3.1; Applied Biosystems). After sequencing of the PCR products, portions of the 16S and 23S rDNA regions were removed to obtain the full ITS sequences. For all VS studied, the 5′ ends of the ITS sequences were CTAAGG, whereas the 3′ ends of the ITS sequences were AATAA. The similarity score for the ITS sequence of a strain was obtained by comparing its sequence with that of the type strain of the same species, and the PileUp command of the Wisconsin Genetics Computer Group (GCG) package (version 10.3; Accelrys Inc., San Diego, Calif.) was used for calculation. The PrettyBox program of the GCG package was used to align multiple ITS sequences.

Phylogenetic analysis.

Multiple-sequence alignment of the ITS sequences was carried out with the CLUSTAL X program (version 1.63b) (37), and an unrooted phylogenetic tree was constructed by using the neighbor-joining method (31) listed in the MEGA (molecular evolutionary genetic analysis; version 2.1) analytical software package (24). For neighbor-joining analysis, the distance between the sequences was calculated by using Kimura's two-parameter model. The robustness of the neighbor-joining method was statistically evaluated by bootstrap analysis with 1,000 bootstrap samples.

Identification of clinical isolates of VS by ITS sequencing.

A total of 106 clinical isolates were tested to evaluate the feasibility of using ITS sequencing for VS identification. These isolates were first identified with the Rapid ID 32 STREP system (bioMérieux Vitek). The ITS sequence of a clinical isolate was compared to those of the type strains (Table 1), and a species name was given according to the highest similarity score obtained. Clinical isolates for which the Rapid ID 32 STREP system and ITS sequence analysis produced discrepant identifications were further identified according to their 16S rDNA sequences.

Species identification by 16S rDNA sequencing.

Primer pair 8FPL (5′-GTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′) and 1492RPL (5′-GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′) was used for PCR amplification (27) of the nearly complete length of the 16S rDNA of clinical isolates for which the Rapid ID 32 STREP system and ITS sequencing produced discrepant identifications. The amplicons were cycle sequenced in both directions by using the two primers described above and an additional primer, primer 1055r (5′-CACGAGCTGACGACAGCCAT-3′). The sequences determined were compared to known 16S rRNA gene sequences in the National Center for Biotechnology Information database by using the BLAST algorithm.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The ITS sequences of 29 reference strains and 1 clinical isolate (a total of 30 sequences) of VS and several streptococcal species were submitted to GenBank. The accession numbers are listed in Table 1.

RESULTS

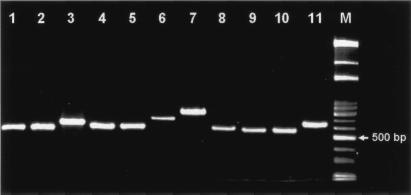

Amplification and sequencing of the ITS fragments. The ITS fragments of 11 species (29 reference strains) of clinically relevant VS were amplified by PCR with primers 13BF and 6R. A single amplicon was observed for each species (Fig. 1). After sequencing and removal of the partial 16S and 23S rDNA portions, the exact lengths and sequences of the ITSs were obtained. S. oralis had the shortest ITS fragment (246 bp), followed by S. mitis (248 to 249 bp), whereas S. constellatus and S. anginosus yielded the longest ITS fragments (390 to 391 bp). Intraspecies variations in ITS lengths were within 3 bp (Table 1).

FIG. 1.

Amplification of VS type strains with primers 13BF and 6R and separation of the PCR products by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. Lanes: 1, S. mitis; 2, S. oralis; 3, S. constellatus; 4, S. intermedius; 5, S. salivarius; 6, S. anginosus; 7, S. mutans; 8, S. sanguinis; 9, S. gordonii; 10, S. parasanguis; 11, S. uberis; M, 100-bp ladder.

Sequence similarities of ITS regions.

Generally, the intraspecies similarity scores were very high, ranging from 0.97 to 1.0 (Table 1). However, an exception was found for S. gordonii; two of the three reference strains (strains ATCC 49818 and ATCC 35105) had similarity scores of only 0.94 each when their sequences were compared with that of the type strain (ATCC 10558). In addition to the 11 species of VS, the ITS accession numbers of several commonly encountered streptococcal species and E. faecalis are also listed in footnote c of Table 1. Some ITS sequences of VS available in GenBank are also included in Table 1 to facilitate intraspecies comparisons. Table 1 demonstrates the high degree of intraspecies conservation of both the lengths and the sequences of the ITS regions.

Table 2 shows the results of pairwise comparisons of the ITS sequences between type strains of any two given species. In addition to the 11 species of VS, type strains of S. agalactiae, S. pyogenes, S. pneumoniae, and E. faecalis were also included for comparison. Table 2 reveals a high level of interspecies divergence of the ITS sequences. Among the type strains of VS, the similarity scores ranged from 0.51 (S. mutans versus S. anginosus) to 0.93 (S. mitis versus S. oralis). However, a high similarity score (0.94) between type strains of S. pneumoniae and S. mitis was also observed (Table 2). In general, the interspecies ITS similarity scores were less than 0.80.

TABLE 2.

ITS sequence similarity scores among type strains of streptococcal and enterococcal species

| Species no. and species | ATCC no. | Sequence similarity score for the following speciesa:

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | ||

| 1. S. agalactiae | 13813 | 0.58 | 0.57 | 0.68 | 0.62 | 0.65 | 0.56 | 0.64 | 0.66 | 0.64 | 0.55 | 0.76 | 0.56 | 0.52 | 0.35 |

| 2. S. anginosus | 33397 | 0.53 | 0.62 | 0.61 | 0.60 | 0.51 | 0.61 | 0.61 | 0.56 | 0.74 | 0.57 | 0.54 | 0.48 | 0.35 | |

| 3. S. constellatus | 27513 | 0.61 | 0.66 | 0.58 | 0.53 | 0.59 | 0.63 | 0.56 | 0.53 | 0.57 | 0.55 | 0.51 | 0.36 | ||

| 4. S. gordonii | 10558 | 0.71 | 0.73 | 0.60 | 0.76 | 0.76 | 0.72 | 0.58 | 0.70 | 0.76 | 0.54 | 0.32 | |||

| 5. S. intermedius | 27335 | 0.69 | 0.56 | 0.69 | 0.69 | 0.66 | 0.57 | 0.62 | 0.70 | 0.53 | 0.34 | ||||

| 6. S. mitis | 49456 | 0.58 | 0.93 | 0.75 | 0.94 | 0.61 | 0.67 | 0.72 | 0.56 | 0.36 | |||||

| 7. S. mutans | 31377 | 0.58 | 0.58 | 0.55 | 0.53 | 0.57 | 0.53 | 0.46 | 0.35 | ||||||

| 8. S. oralis | 35037 | 0.77 | 0.90 | 0.60 | 0.68 | 0.73 | 0.56 | 0.35 | |||||||

| 9. S. parasanguinis | 15912 | 0.72 | 0.60 | 0.68 | 0.73 | 0.51 | 0.35 | ||||||||

| 10. S. pneumoniae | 33400 | 0.57 | 0.67 | 0.72 | 0.52 | 0.35 | |||||||||

| 11. S. pyogenes | 14289 | 0.55 | 0.53 | 0.49 | 0.33 | ||||||||||

| 12. S. salivarius | 13419 | 0.54 | 0.52 | 0.36 | |||||||||||

| 13. S. sanguinis | 10556 | 0.51 | 0.37 | ||||||||||||

| 14. S. uberis | 13386 | 0.34 | |||||||||||||

| 15. E. faecalis | 19433 | ||||||||||||||

The species numbers correspond to the species numbers identified on the left.

Table 3 shows the results of intra- and interspecies comparisons of the ITS sequences between strains of S. mitis, S. oralis, and S. pneumoniae. It was noted that S. pneumoniae could not be differentiated from S. mitis by the similarity scores for the ITS sequences. For example, the similarity score between the type strains of S. pneumoniae ATCC 33400 and S. mitis ATCC 49456 (0.99) was higher than the intraspecies similarity score between S. mitis ATCC 49456 and S. mitis SK24 (0.98).

TABLE 3.

Intraspecies and interspecies ITS sequence similarity scores among strains of S. mitis, S. oralis, and S. pneumoniae

| Species no. and species | ATCC no. | Sequence similarity score for the following speciesa:

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | ||

| 1. S. mitis | 49456b | 0.98 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.99 | 0.95 | 1.00 |

| 2. S. mitis | SK24c | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.99 | 0.94 | 0.99 | |

| 3. S. oralis | 49296 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.90 | 0.93 | 0.90 | 0.95 | ||

| 4. S. oralis | 9811 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.89 | 0.93 | 0.89 | 0.94 | |||

| 5. S. oralis | 10557c | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.90 | 0.93 | 0.90 | 0.95 | ||||

| 6. S. oralis | 35037b | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.89 | 0.93 | 0.89 | 0.94 | |||||

| 7. S. oralis | 55229 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.90 | 0.93 | 0.90 | 0.95 | ||||||

| 8. S. oralis | 700233 | 0.99 | 0.90 | 0.93 | 0.90 | 0.95 | |||||||

| 9. S. oralis | 700234 | 0.89 | 0.93 | 0.89 | 0.94 | ||||||||

| 10. S. pneumoniae | M60763c | 0.93 | 0.99 | 0.95 | |||||||||

| 11. S. pneumoniae | 33400b | 0.93 | 0.98 | ||||||||||

| 12. S. pneumoniae | 27336 | 0.95 | |||||||||||

| 13. S. pneumoniae | 49169 | ||||||||||||

The species numbers correspond to the species numbers identified on the left.

Type strains.

Strains that were not obtained from ATCC but whose ITS sequences were available in the GenBank database.

The ITS sequences of S. mitis and S. oralis also have high similarity scores. The intraspecies similarity scores for the ITS regions ranged from 0.98 to 1.0 and from 0.99 to 1.0 for S. mitis and S. oralis strains, respectively (Table 3). However, the interspecies similarity scores between strains of the two species (0.93 to 0.95) were consistently lower than those observed for strains within each species. Therefore, S. mitis strains could be effectively differentiated from S. oralis strains on the basis of their ITS sequences. Moreover, it was interesting that all six reference strains of S. oralis had a single deletion at ITS nucleotide positions 199 and 217 of S. mitis; however, the nucleotides were A and T at these two positions in the type strain of S. mitis (ATCC 49456) and S. mitis SK24 (GenBank accession no. AB051020), respectively. Another important characteristic that could be used to differentiate S. mitis from S. oralis was that the ITS lengths in S. mitis (248 to 249 bp) were consistently 2 to 3 bp longer than those in S. oralis (246 bp) (Table 1).

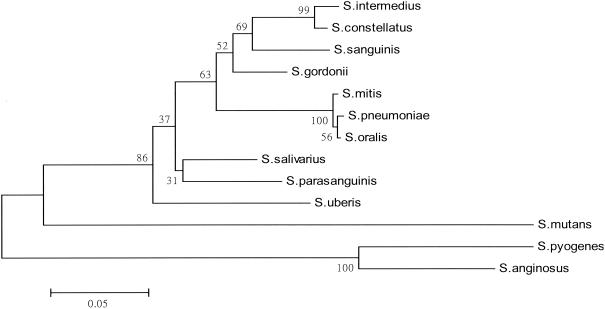

Phylogenetic relationships.

The phylogenetic relationships derived from the ITS sequences of the 11 type strains of VS and the type strains of S. pneumoniae and S. pyogenes are presented in Fig. 2. The phylogenetic tree constructed revealed that strains of the mitis group (S. mitis and S. oralis) and S. pneumoniae were highly related and grouped together. However, it was noted that S. parasanguinis did not cluster with the other two species (S. gordonii and S. sanguinis) constituting the sanguinis group. In addition, S. anginosus was genetically separated from S. constellatus and S. intermedius of the anginosus group and from the other nine species of VS in the phylogenetic tree.

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic relationship of various species of VS, S. pneumoniae, and S. pyogenes on the basis of the ITS sequences. The phylogenetic tree was generated by the neighbor-joining method within the MEGA package. The numbers at the nodes are the percentages of occurrence in 1,000 bootstrapped resamplings.

Identification of clinical isolates of VS by ITS sequencing.

A total of 106 clinical isolates were analyzed to validate ITS sequencing for identification of VS. Overall, the species identities obtained with the Rapid ID 32 STREP system and by ITS sequence analysis showed 82% (87 isolates) agreement. Concordant identifications were obtained for the following species (with the numbers of isolates indicated in parentheses): S. anginosus (n = 11), S. constellatus (n = 12), S. gordonii (n = 2), S. intermedius (n = 12), S. mitis (n = 9), S. mutans (n = 8), S. oralis (n = 11), S. parasanguinis (n = 1), S. salivarius (n = 11), S. sanguinis (n = 8), and S. uberis (n = 2). It was interesting that all clinical isolates of S. mitis and S. oralis analyzed in this study possessed the same characteristics as the reference strains, i.e., either the presence or the absence of A and T residues at ITS nucleotide positions 199 and 217, respectively.

The 19 (18%) clinical isolates for which the Rapid ID 32 STREP system and ITS sequencing produced discrepant identifications are listed in Table 4. Strains that produced discrepant results were usually given an “unacceptable profile” or low identification percentages with the Rapid ID 32 STREP system. Conversely, the ITS sequence identities were greater than 96.7% for all strains with discrepant results (Table 4), as comparisons were made between these strains and the respective type strains. The strains for which discrepant identifications tended to be produced were species of the anginosus group (S. anginosus, S. constellatus, and S. intermedius), species of the mitis group (S. mitis and S. oralis), and S. gordonii (Table 4). Nine discrepant results were caused by the identification of S. parasanguinis strains with the Rapid ID 32 STREP system. Four strains phenotypically identified as S. intermedius with the Rapid ID 32 STREP system were determined to be S. anginosus by the present molecular approach.

TABLE 4.

Clinical isolates of VS for which discrepant identifications were produced with the Rapid ID 32 STREP system and by ITS sequence analysis

| Strain | Species identification by:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| ITS sequencinga | Rapid ID 32 STREP systemb | 16S rDNA sequencingc | |

| 1590 | S. gallolyticus (99) | NId (UA) | S. gallolyticus (99) |

| 336 | S. anginosus (99.5) | S. parasanguinis (UA) | S. anginosus (99) |

| 5437 | S. anginosus (96.7) | S. intermedius (98.2) | S. anginosus (99.3) |

| 6347 | S. anginosus (98.4) | S. intermedius (97.3) | S. anginosus (96) |

| 7940 | S. anginosus (98.4) | S. oralis (UA) | S. anginosus (99) |

| 8234-2 | S. anginosus (99.5) | S. intermedius (98.7) | S. anginosus (99) |

| MyP700 | S. anginosus (96.7) | S. intermedius (98.2) | S. anginosus (98) |

| 737 | S. constellatus (100) | S. parasanguinis (UA) | S. constellatus (98) |

| 4938 | S. constellatus (99.6) | S. parasanguinis (UA) | S. constellatus (99) |

| 4672 | S. gordonii (98.7) | S. parasanguinis (UA) | S. gordonii (99) |

| 6826 | S. gordonii (99.1) | S. parasanguinis (UA) | S. gordonii (97.7) |

| 2000 | S. mitis (99.1) | S. parasanguinis (UA) | S. oralis (98), S. mitis (98) |

| 8916 | S. mitis (99.1) | S. oralis (UA) | S. mitis (99), S. sanguinis (99) |

| 3788-2 | S. mitis (99.1) | S. parasanguinis (UA) | S. mitis (98), S. oralis (97) |

| 8903-2 | S. mitis (98.3) | S. thermophilus (UA) | S. mitis (98), S. pneumoniae (98) |

| 8984 | S. oralis (100) | S. mitis (97.5) | S. mitis (97), S. oralis (97) |

| 5881-2 | S. oralis (99.5) | S. parasanguinis (72) | S. mitis (99.8), S. oralis (98.4) |

| 5129-2 | S. oralis (99.5) | S. parasanguinis (91) | S. mitis (98), S. oralis (97.7) |

| 7520 | NI | S. sanguinis (89.1) | S. siemens (99) |

The values in parentheses are the percent identities of the strains studied compared to the sequence of the corresponding type strain.

The values in parentheses are the percent identities obtained with the Rapid ID 32 STREP system. UA, unacceptable profile.

The values in parentheses are the percent 16S rDNA sequence identities with the sequences available in GenBank.

NI, not identified.

The 19 strains with discrepant results were further identified by 16S rDNA sequencing. Except for strains of S. mitis and S. oralis, the identities of all 11 strains of other species identified by ITS sequencing were confirmed by sequencing of their 16S rDNA (Table 4). Among the seven strains identified as S. mitis or S. oralis by ITS sequencing, their 16S rDNA sequences always matched those of both S. mitis and S. oralis with very high scores by use of database searches with the BLAST program. The ITS sequence of strain 1590 had a similarity of 99% with that of S. gallactolyticus ATCC 9809, whose ITS sequence we sequenced and submitted to GenBank (GenBank accession no. AY347542). The 16S rDNA sequence of strain 1590 also had 99% identity with that of S. gallactolyticus ATCC 43143 in the GenBank database. Strain 7520 was not identified by ITS sequencing; however, it was identified as S. sanguinis and S. siemens with the Rapid ID 32 STREP system and by 16S rDNA sequencing, respectively. Because the 16S rDNA sequence of strain 7520 had a 99% identity with that of S. siemens (strain HK; GenBank accession no. AF432856), this strain was considered to be S. siemens.

DISCUSSION

This study has described a method that could identify clinically relevant VS to the species level. The method consists of (i) a PCR with two universal primers for amplification of a fragment encompassing the ITS sequence and partial regions of the 16S and 23S rDNAs, (ii) sequencing of the amplicon, and (iii) comparison of the ITS sequence with those of the type and reference strains of VS. The whole procedure can be finished within 24 h if isolated colonies are available. This method might be useful under conditions that necessitate identification of VS to the species level. It provides an accurate alternative for the delineation of some species of VS that are difficult to identify.

PCR amplification of the ITS regions depends on the occurrence of highly conserved regions in the flanking termini of the 16S and 23S rRNA genes. The primers used in this study (primers 13BF and 6R) also could efficiently amplify the ITS regions of nutritionally variant streptococci and streptococci other than VS by using the PCR conditions specified here (data not shown). Whiley et al. (40) found that some atypical strains of the anginosus group produced PCR products whose lengths were different from those of “normal” strains. However, most of these atypical strains were eventually found to be misclassified, as further examined by DNA-DNA reassociation experiments (40).

Pairwise comparison of two given species of VS revealed a lower level of sequence similarity between their ITS regions (Table 2) than between their 16S rDNA sequences (20). These results indicate that the ITS region might constitute a more discriminative target sequence than 16S rDNA for the differentiation of closely related species of VS. It was found that considerable variation in both the lengths and the sequences of the ITS regions can occur between species (14). The ITS region has been suggested to be a suitable target from which useful taxonomic information for bacteria can be derived, particularly with regard to identification to the species level (3, 16, 28, 34, 39) and genotyping (13, 14). A limitation for bacterial identification based on ITS sequencing is the limited availability of ITS sequences; however, the numbers of ITS region sequences available in public databases has increased rapidly in recent years.

16S rDNA sequencing (sequence length, approximately 1.5 kb) is well established as a standard method for the identification of species, genera, and families of bacteria (2). However, the ITS lengths of VS are relatively short (246 to 391 bp) (Table 1), and sequencing of the ITS region would be easier and more straightforward. In this study, each of the 11 clinically important species of VS produced a single PCR product that facilitated direct sequencing (Fig. 1).

In this study, four strains identified as S. intermedius with the Rapid ID 32 STREP system were actually S. anginosus, as revealed by their ITS and 16S rDNA sequences. However, strains identified as S. parasanguinis with the Rapid ID 32 STREP system could be S. anginosus, S. constellatus, or S. gordonii (Table 4). Jacobs et al. (19) reported that bloodstream isolates of S. anginosus are frequently identified as S. intermedius with the Rapid ID 32 STREP system.

The groESL (36) and sodAint (26) genes have been used for differentiation of species of VS and streptococci, respectively. Since sequence heterogeneity of these two genes exists among different species, highly degenerate primers were used to amplify the two genes from different species. The disadvantage of using highly degenerate primers is that the annealing temperature of the PCR must be low enough to ensure effective pairing of the primers and the template DNA. However, under low-stringency conditions, the chances of producing aberrant PCR products might increase. The drawback of using the sodAint gene for the identification of streptococci is that the intraspecies sequence divergence may vary greatly, depending upon the species considered. Therefore, the identification of species can be made only by determining the positions of their sodAint sequences on the phylogenetic tree constructed from type strains (26). In addition, S. mitis and S. oralis cannot be differentiated by sequence analysis of the groESL (36) and sodAint (26) genes, since intraspecies sequence variations are greater than interspecies variations.

Kikuchi et al. (21) found that among the 17 strains identified as S. mitis with the Rapid ID 32 STREP system, the results for only 3 strains were in agreement with the results of DNA-DNA hybridization. Jacobs et al. (19) reported that bloodstream isolates identified as S. oralis are mainly those previously identified as S. mitis. The 16S rDNA sequence identities of type strains of S. oralis (ATCC 35037) and S. mitis (ATCC 49456) are greater than 99% (20). After pairwise comparisons of the 16S rDNA sequences of six reference strains of S. mitis (ATCC 903, ATCC 6249, ATCC 15914, ATCC 49456, NCTC 12261, and NCTC 3165) and four reference strains of S. oralis (ATCC 700233, ATCC 9811, ATCC 35037, and NCTC 11427) available in the GenBank database, it was found that the intraspecies sequence variations (0.93 to 1.0) were higher than the interspecies sequence variations (0.96 to 1.0). Therefore, identification of S. mitis and S. oralis on the basis of 16S rDNA sequence analysis may not be reliable. This phenomenon was clearly demonstrated in the present study (Table 4). An analysis with the BLAST algorithm showed that the 16S rDNA sequences of strains identified as S. mitis by their ITS sequences always matched the 16S rRNA gene sequences of both S. mitis and S. oralis with high degrees of identity. This was also true for S. oralis strains.

However, S. mitis could easily be differentiated from S. oralis by ITS sequence comparison (Table 3) or sequence alignment. The intraspecies ITS similarity scores for both species were higher than the interspecies ITS similarity scores (Table 3). In addition, all seven reference strains of S. oralis had one deletion at ITS nucleotide positions 199 and 217, and this characteristic could be used as a fingerprint to differentiate species of S. oralis and S. mitis. However, the intraspecies ITS divergence of S. mitis and S. pneumoniae was higher than the interspecies divergence of the two species (Table 3). Therefore, simple biochemical tests such as optochin susceptibility and bile solubility tests should be used to differentiate S. pneumoniae from S. mitis; both tests are positive for S. pneumoniae, whereas S. mitis is optochin resistant and bile insoluble (9).

From the phylogenetic tree constructed by use of the ITS sequences, S. parasanguinis and S. anginosus did not cluster with their respective groups (the sanguinis group and the anginosus group, respectively). However, S. mitis, S. oralis, and S. pneumoniae were related and grouped together (Fig. 2). These three species were also grouped together when the genes encoding groESL (36), sodAint (26), and 16S rRNA (6, 20) were analyzed. Many bootstrap values shown in the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 2) were less than 70%; therefore, the ITS region may not be a good target for constructing a phylogenetic tree for species of VS. This implies that there exists an unparallel evolution between the ITS region and the 16S rRNA gene that is essential for the survival of all microorganisms.

In conclusion, identification of species of VS by ITS sequencing seems to be reliable and could be used as an accurate alternative for the identification of VS.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by a grant (grant NSC 88-2314-B006-078) from the National Science Council and in part by a grant from the Department of Medical Research of the National Taiwan University Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan.

We thank S. Liu for help with constructing the phylogenetic tree and S. K. Tung for assistance with 16S rDNA sequencing.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmet, Z., M. Warren, and E. T. Houang. 1995. Species identification of members of the Streptococcus milleri group isolated from the vagina by ID 32 Strep system and differential phenotypic characteristics. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:1592-1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amann, R. I., W. Ludwig, and K.-H. Schleifer. 1995. Phylogenetic identification and in situ detection of individual microbial cells without cultivation. Microbiol. Rev. 59:143-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barry, T., G. Colleran, M. Glennon, L. K. Dunican, and F. Gannon. 1991. The 16S/23S ribosomal spacer region as a target for DNA probes to identify eubacteria. PCR Methods Appl. 1:51-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beighton, D., J. M. Hardie, and A. Whiley. 1991. A scheme for the identification of viridans streptococci. J. Med. Microbiol. 35:367-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bentley, R. W., and J. A. Leigh. 1995. Development of PCR-based hybridization protocol for identification of streptococcal species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:1296-1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bentley, R. W., J. A. Leigh, and M. D. Collins. 1991. Intrageneric structure of Streptococcus based on comparative analysis of small-subunit rRNA sequences. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 41:487-494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang, W. N., J. J. Wu, C. R. Huang, Y. C. Tsai, C. C. Chien, and C. H. Lu. 2002. Identification of viridans streptococcal species causing bacterial meningitis in adults in Taiwan. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 21:393-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clarridge, J. E., III, S. M. Attorri, Q. Zhang, and J. Bartell. 2001. 16S ribosomal DNA sequence analysis distinguishes biotypes of Streptococcus bovis: Streptococcus bovis biotype II/2 is a separate genospecies and the predominant clinical isolate in adult males. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:1549-1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Facklam, R. 2002. What happened to the streptococci: overview of taxonomic and nomenclature changes. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15:613-630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flynn, C. E., and K. L. Ruoff. 1995. Identification of Streptococcus milleri group isolates to the species level with a commercially available rapid test. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2704-2706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garnier, F., G. Gerbaud, P. Courvalin, and M. Galimand. 1997. Identification of clinically relevant viridans group streptococci to the species level by PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:2337-2341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gheldre, Y. D., P. Vandamme, H. Goossens, and M. J. Struelens. 1999. Identification of clinically relevant viridans streptococci by analysis of transfer DNA intergenic spacer length polymorphism. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 49:1591-1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gurtler, V. 1993. Typing of Clostridium difficile strains by PCR-amplification of variable length 16S-23S rDNA spacer regions. J. Gen. Microbiol. 139:3089-3097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gurtler, V., and H. D. Barrie. 1995. Typing of Staphylococcus aureus strains by PCR-amplification of variable-length 16S-23S rDNA spacer regions: characterization of spacer sequences. Microbiology 141:1255-1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gurtler, V., and V. A. Stanisich. 1996. New approaches to typing and identification of bacteria using the 16S-23S rDNA spacer region. Microbiology 142:3-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamid, M. E., A. Roth, O. Landt, R. M. Kroppenstedt, M. Goodfellow, and H. Mauch. 2002. Differentiation between Mycobacterium farcinogenes and Mycobacterium senegalense strains based on 16S-23S ribosomal DNA internal transcribed spacer sequences. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:707-711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hillman, J. D., S. W. Andrews, S. Painetr, and P. Stashenko. 1989. Adaptative changes in a strain of Streptococcus mutans during colonization of the human oral cavity. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 2:231-239. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacobs, J. A., C. S. Schot, A. E. Bunschoten, and L. M. Schouls. 1996. Rapid species identification of “Streptococcus milleri” strains by line blot hybridization: identification of a distinct 16S rRNA population closely related to Streptococcus constellatus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:1717-1721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacobs, J. A., H. C. Schouten, E. E. Stobberingh, and P. B. Soeters. 1995. Viridans streptococci isolated from the bloodstream. Relevance of species identification. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 22:267-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawamura, Y., X. Hou, F. Sultana, H. Miura, and T. Ezaki. 1995. Determination of 16S rRNA sequences of Streptococcus mitis and Streptococcus gordonii and phylogenetic relationships among members of the genus Streptococcus. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 45:406-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kikuchi, K., T. Enari, K. Totsuka, and K. Shimizu. 1995. Comparison of phenotypic characteristics, DNA-DNA hybridization results, and results with a commercial rapid biochemical and enzymatic reaction system for identification of viridans group streptococci. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:1215-1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kilian, M., L. Mikkelsen, and J. Henrichsen. 1989. Taxonomic studies of viridans streptococci: description of Streptococcus gordonii sp. nov. and emended descriptions of Streptococcus sanguis (White and Niven 1946), Streptococcus oralis (Bridge and Sneath 1982), and Streptococcus mitis (Andrewes and Horder 1906). Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 39:471-484. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kilpper-Bälz, R., B. L. Williams, R. Lutticken, and K. H. Schleifer. 1984. Relatedness of “Streptococcus melleri” with Streptococcus anginosus and Streptococcus constellatus. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 5:494-500. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar, S., K. Tamura, and M. Nei. 1993. MEGA: molecular evolutionary genetic analysis, version 1.01. The Pennsylvania State University, University Park.

- 25.Millar, B. C., X. Jiru, J. E. Moore, and J. A. Earle. 2000. A simple and sensitive method to extract bacterial, yeast and fungal DNA from blood culture material. J. Microbiol. Methods 42:139-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poyart, C., G. Quesne, S. Coulon, P. Berche, and P. Trieu-Cuot. 1998. Identification of streptococci to species level by sequencing the gene encoding the manganese-dependent superoxide dismutase. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:41-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Relman, D. A. 1993. Universal bacterial 16S rDNA amplification and sequencing, p. 489-495. In D. H. Persing, T. F. Smith, F. C. Tenover, and T. J. White (ed.), Diagnostic molecular microbiology. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 28.Roth, A., M. Fischer, M. E. Hamid, S. Michalke, W. Ludwig, and H. Mauch. 1998. Differentiation of phylogenetically related slowly growing mycobacteria based on 16S-23S rRNA gene internal transcribed spacer sequences J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:139-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rudney, J. D., and C. J. Larson. 1999. Identification of oral mitis group streptococci by arbitrary primed polymerase chain reaction. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 14:33-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saarela, M., S. Alaluusua, T. Takei, and S. Asikainen. 1993. Genetic diversity within isolates of mutans streptococci recognized by an rRNA gene probe. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:584-587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saitou, N., and M. Nei. 1987. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic tree. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4:406-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schmidhuber, S., W. Ludwig, and K. H. Schleifer. 1988. Construction of a DNA probe for the specific identification of Streptococcus oralis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 26:1042-1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shenep, J. L. 2000. Viridans-group streptococcal infections in immunocompromised hosts. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 14:129-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suffys, P. N., A. da Silva Rocha, M. de Oliveira, C. E. Dias Campos, A. M. Werneck Barreto, F. Portaels, L. Rigouts, G. Wouters, G. Jannes, G. van Reybroeck, W. Mijs, and B. Vanderborght. 2001. Rapid identification of mycobacteria to the species level using INNO-LiPA mycobacteria, a reverse hybridization assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:4477-4482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Teng, L. J., P. R. Hsueh, S. W. Ho, and K. T. Luh. 1998. Antimicrobial susceptibility of viridans group streptococci in Taiwan with an emphasis on the high rates of resistance to penicillin and erythromycin in Streptococcus oralis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 41:621-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Teng, L.-J., P.-R. Hsueh, J.-C. Tsai, P.-W. Chen, J.-C. Hsu, H.-C. Lai, C.-N. Lee, and S.-W. Ho. 2002. groESL sequence determination, phylogenetic analysis, and species differentiation for viridans group streptococci. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:3172-3178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thompson, J. D., T. J. Gibson, F. Plewniak, F. Jeanmougin, and D. G. Higgins. 1997. The CLUSTAL X Windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:4876-4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tracy, M., A. Wanahita, Y. Shuhatovich, E. A. Goldsmith, J. E. Clarridge, and D. M. Musher. 2001. Antibiotic susceptibilities of genetically characterized Streptococcus milleri group strains. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1511-1514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Uemori, T., K. Asada, I. Kato, and R. Harasawa. 1992. Amplification of the 16S-23S spacer region in rRNA operons of mycoplasmas by the polymerase chain reaction. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 15:181-186. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Whiley, R. A., B. Duke, J. M. Hardie, and L. M. C. Hall. 1995. Heterogeneity among 16S-23S rRNA intergenic spacers of species within the “Streptococcus milleri group.” Microbiology 141:1461-1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]