Abstract

Korean Americans represent one of the fastest growing Asian subpopulations in the United States. Despite a dramatic reduction in incidence nationwide, cervical cancer remains a major threat for Korean American women. By preventing the strains of the Human Papillomavirus (HPV) known to cause cervical cancer, the HPV vaccines appear to be a promising solution to reduce the persistent disparities in cervical cancer among not only Korean Americans, but also other racial and ethnic minorities more generally. However, current literature lacks a better understanding of how cultural and behavioral factors influence Korean American women’s intention to vaccinate their adolescent daughters against HPV. This manuscript presents the results of testing the mechanisms through which interdependent self-construal (an orientation of self in which individuals define themselves primarily through their relationships with others), attitudes, and subjective norms impact Korean American mothers’ intention to vaccinate their daughters. Our findings suggest that self-construal holds promise for health communication research to not only uncover the rich variance of health-related beliefs among individuals of shared cultural descent, but also to understand the context in which these beliefs are embedded.

Keywords: cervical cancer, HPV vaccine, Korean American, self-construal, immigrant

Health disparities occur when an unequal burden of particular health problems appears in certain segments of the population due to their demographic, socioeconomic, environmental, and geographic characteristics (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2011). Despite over 40 years of research and intervention in the United States, disparities in health-related outcomes among racial/ethnic populations not only continue, but are widening (CDC, 2011; Kagawa Singer, 2012). Strategies to diminish such health disparities become even more pressing given the exponential increase, in the past decade, of the populations of ethnic minorities in the United States. The current paper focuses on one specific health disparity – acceptance of vaccinating one’s child against the Human Papillomavirus or HPV, among one of the fastest growing segments of the U.S. population, namely Korean Americans. Below we describe the existing disparity and then explore the extent to which factors such as attitudes, subjective norms and interdependent self-construal1 may influence Korean American parents’ willingness to vaccinate their adolescent daughters.

Korean Americans represent one of the fastest growing segments of the U.S. Asian populations among all detailed Asian groups (either alone or in any combination ) that have a population over one million or more (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010). But, as with other ethnic minorities, the incidence of cancer among Korean Americans does not reflect the remarkable gains made in recent decades among the U.S. population as a whole (H. Y. Lee, Ju, Vang, & Lundquist, 2010; Yoo & Wood, 2013). More specifically, despite a dramatic reduction in incidence nationwide, cervical cancer remains a major threat for Korean American women (M. C. Lee, 2000; Y.S. Lee et al., 2012; McCracken et al., 2007). Although national data are unavailable for Asian subgroups, California statistics indicate that Korean American women have one of the highest levels of cervical cancer incidence and mortality (McCracken et al., 2007); and the lowest level of cervical cancer screening (H. Y. Lee, et al., 2010; McCracken, et al., 2007). Korean American women’s lack of cervical cancer screening has been associated with low English proficiency (Fang, Ma, & Tan, 2011; E. E. Lee, Fogg, & Menon, 2008), insufficient recognition of the necessity of prevention (Y.S. Lee, Roh, Vang, & Jin, 2011; Oh et al., 2010), and traditional cultural values that women should sacrifice their own needs to fulfill their obligations toward their family (Im, Lee, Park, & Salazar, 2002; E. E. Lee, et al., 2008).

The Human Papillomavirus or HPV has been identified as the predominant cause of cervical cancer (CDC, 2012b). In 2006, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the use of two vaccines, both highly effective in guarding against HPV types 16 and 18, two high risk strains of HPV responsible for 70 percent of cervical cancer (National Cancer Institute [NCI], 2011). Gardasil is recommended for both females and males between the ages of 9 to 26, and the other vaccine, Cervarix, for females ages 9 to 26 (NCI, 2011). Both vaccines are recommended to be administered in three injections over a 6-month period to ensure full protection (NCI, 2011). These HPV vaccines represent one of the most promising opportunities to mitigating an existing health disparity.

Since HPV infections are sexually transmitted, the CDC recommends that the HPV vaccine ideally be administered prior to sexual initiation (CDC, 2012a). Consequently, there has been a strong push for promoting uptake of the HPV vaccine among early adolescents (Garcini, Galvan, & Barnack-Tavlaris, 2012; Trim, Nagji, Elit, & Roy, 2012). In light of the pivotal role parents play in the vaccination of their children, understanding the factors that influence a parent’s decision to vaccinate or not vaccinate becomes crucial (Trim, et al., 2012). In fact, current research appears to indicate that parental intention to vaccinate their children against HPV has been gradually declining nationwide (Darden et al., 2013; Trim et al., 2012). For example, a systematic review of recent studies on HPV or HPV vaccine indicated that the percentage of parents who intended to vaccinate their children decreased from 80% in 2008 to 41% in 2011 (Trim et al., 2012). Similarly, reports from the National Immunization Survey for Teens revealed that the percentage of parents refusing to vaccinate their female teens with HPV rose from 39.8% in 2008 to 43.9 % in 2010 (Darden et al., 2013).

Since the approval of the vaccines in 2006 there has been a proliferation of evidence regarding the socioeconomic and behavioral determinants for parental acceptance of HPV vaccination; for instance, parental intention to vaccinate their adolescent children against HPV has been frequently associated with physician recommendation as well as parental knowledge and beliefs with respect to HPV and the HPV vaccines (Darden et al., 2013; Garcini et al., 2012; Trim et al., 2012). Much of this literature, however, is limited on at least two fronts. First, the vast majority of these studies were based on Caucasian or European American samples, leaving Asian Americans, either as a whole or as specific ethnic subpopulations, largely understudied (Allen et al., 2010). Second, there is a growing recognition in public health that an individual’s culture plays a critical role in shaping their health-related decisions and overall well-being (Kagawa Singer, 2012; Sherman, Uskul, & Updegraff, 2011). This appears to be especially true for racial/ethnic minority populations (Kreuter & McClure, 2004). Yet research that examines the association between cultural factors and parental acceptance of HPV vaccination is scarce (Allen et al., 2010).

The primary purpose of this study is to examine potential determinants of Korean American women’s intention to have their adolescent daughters vaccinated against HPV. Specifically, we focus on the extent to which interdependent self-construal (an orientation of self in which individuals define themselves primarily through their relationships with others), attitudes, and perceived subjective norms (what individuals believe about the expectations of others with respect to vaccinating their daughters) predict Korean American mothers’ intention to vaccinate their 13 year old daughters against HPV. Our secondary purpose is to explore whether self-construal makes a unique contribution in explaining the intention to vaccinate one’s daughter over and above English linguistic proficiency, a frequently cited factor associated with Korean American women’s utilization of prevention service (Fang, et al., 2011; E. E. Lee, et al., 2008). Given the relatively high rates of cervical cancer among Korean American women and the prospect that the HPV vaccination might effectively curb this unequal burden for future generations, we consider this study timely, innovative, and significant.

Self-Construal

Self-construal is defined as the way individuals see themselves in relation to others (Markus & Kitayama, 1991). Independent and interdependent views of self have been identified as “among the most general and overarching schemata of the individual’s self-system” (Markus & Kitayama, 1991; p.230). People with an elaborated independent self-construal see themselves as a unique entity relatively unconfined by their relational context. They tend to value the expression of personal attributes (e.g. talent, ability) and the virtues of individual autonomy in decision-making. Consequently, their behaviors are primarily driven by their own thoughts, feelings, and actions.

In contrast, individuals with a strong interdependent view of self tend to define themselves with reference to important social relationships (e.g. family, working group) (Markus & Kitayama, 1991). The role of one’s internal attributes in regulating overt behaviors is secondary and subject to situational demands. As a result, the behaviors of interdependently-oriented individuals are largely based on their consideration of the thoughts, feelings, and actions of specific others in particular social contexts.

The potential health implications of these divergent views of self have received growing attention in health communication research. Studies that tailor health messages to an individual’s view of self have found that such messages produced greater message acceptance and, in some cases, more favorable behavioral changes (Sherman, et al., 2011; Uskul & Oyserman, 2010; Yu & Shen, 2012). For example, one study found that AIDS messages that threatened one’s family invoked more fear among Mexican immigrant youth and other collectivist participants, than messages that threatened one’s self (Sampson et al., 2001). In another study of Hispanic women, holding a strong interdependent self-construal was positively associated with preferences for receiving breast health information from significant others, friends, and family members (Oetzel, De Vargas, Ginossar, & Sanchez, 2007).

It is generally accepted that an independent self-construal is likely to be associated with individualistic cultures, such as the United States; whereas an interdependent self-construal is more prevalent in collectivistic cultures, such as countries in Eastern Asia, including China, Japan, and Korea (Cross, Hardin, & Gercek-Swing, 2011; Markus & Kitayama, 1991). It is also acknowledged that despite these general tendencies, a considerable amount of variation might exist among individual members regarding which type of self-construal they endorse more strongly than the other (Markus & Kitayama, 1991).

Past research has demonstrated the link between traditional Korean culture and interdependent self-construal (H.-R. Lee, Ebesu Hubbard, O'Riordan, & Kim, 2006; Park & Levine, 1999). Moreover, there is empirical evidence to suggest that an interdependent self-construal plays a critical role in health-related decision-making for individuals of Korean descent. For example, compared to European Americans, Korean Americans were found to be significantly less likely to believe that patients suffering from terminal disease should be fully informed regarding their diagnosis and prognosis. They were also more likely to agree that the patients’ family should make the decision about using life-prolonging technology on behalf of the patients (Blackhall et al., 1999; Blackhall, Murphy, Frank, Michel, & Azen, 1995; Murphy, 1998). This family-centered model of medical decision making was consistent with an interdependent self-construal; as reflected in Korean American participants’ deep concern for the patients and their strong desire to spare the patients from the burden of making difficult health care decisions (Blackhall et al., 1999).

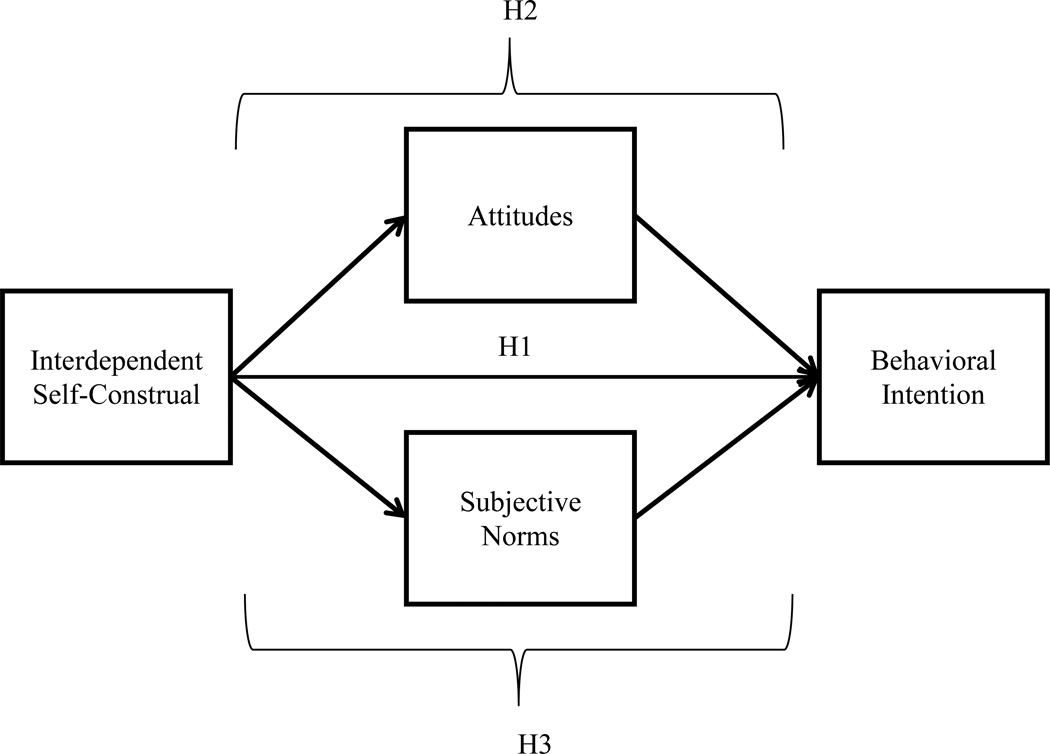

The first hypothesis of the present study thus proposes a direct effect of interdependent self-construal on Korean American women’s intention to vaccinate their adolescent daughters. Because interdependently-oriented individuals typically behave in a way to prioritize the well-being of others with whom they have an important relationship, we expect a positive association between interdependent self-construal and intention to vaccinate one’s daughter (see Figure 1).

H1: An interdependent self-construal will be positively associated with Korean American women’s intention to have their adolescent daughters vaccinated against HPV.

Figure 1.

Hypothetical relationships between interdependent self-construal, attitudes, subjective norms, and behavioral intention

Attitudes and Interdependent Self-construal

Attitudes describe people’s position with respect to performing a specific behavior (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1973). Attitudes have been shown to predict a wealth of diverse health behaviors such as excessive alcohol consumption (Keyes et al., 2012), substance use (Kam, Matsunaga, Hecht, & Ndiaye, 2009), condom use (F. Rhodes, Stein, Fishbein, Goldstein, & Rotheram-Borus, 2007), HIV-risk behaviors (Bleakley, Hennessy, Fishbein, & Jordan, 2011), mammography uptake (Smith-McLallen & Fishbein, 2008), and cervical cancer screening (E. E. Lee, et al., 2008; Watts et al., 2009). In the HPV vaccination literature, parental attitudes toward the importance and safety of vaccination have been among the most frequently assessed constructs in understanding parents’ acceptance of HPV vaccination (Allen et al., 2010). For instance, a recent study found that among parents who did not intend to vaccinate their female teens against HPV, the most frequently cited reasons for not vaccinating were “not needed or not necessary”, and “safety concerns/side effects” (Darden et al., 2013). However, given the heavy reliance on largely Caucasian samples in this literature, little is known regarding how such attitudes affect other ethnic minorities, and specifically Korean American women’s intention to vaccinate their adolescent daughters.

There is both theoretical and empirical justification to expect attitudes toward HPV vaccination to mediate the relationship between interdependent self-construal and intention to have one’s own daughter vaccinated. As noted above, individuals with a strong interdependent view of self tend to regulate their behaviors by referencing to the thoughts, feelings, and well-being of others with whom they have important social relationships (Markus & Kitayama, 1991). This proposition is also reflected in major theories of behavior change. For example, the integrative model of behavioral prediction (IMBP) (Fishbein & Cappella, 2006) proposes that individuals’ cultural characteristics (e.g. self-construal) pertain primarily to stable distal predictors, who’s behavioral influence tend to be mediated by more proximal predictors (e.g. attitudes). Applying the theory of planned behaviors (Ajzen, 1985, 1991), one of the precursor models of IMBP, Park and Levine (1999) found that interdependent self-construal was positively associated with college students’ attitudes toward studying hard for an upcoming exam when the behavioral outcomes were framed as affecting others rather than oneself. Another recent study reports similar patterns in which individuals with a strong interdependent self-construal were more likely to exhibit message-consistent attitudes when the message addressed relational consequences of adopting preventive behaviors such as getting a flu vaccination (Yu & Shen, 2012).

Because HPV vaccination is designed to prevent contracting the most prevalent types of viruses that could cause a life-threatening but totally preventable cancer, a woman’s decision to have her adolescent daughters vaccinated directly affects the future well-being of her children. Consequently, we hypothesize the following,

H2: Korean American women’s attitudes toward the importance (H2a) and safety (H2b) of HPV vaccination will mediate the relationship between interdependent self-construal and behavioral intention to vaccinate their daughters.

That is, having an interdependent self-construal will be positively associated with pro-vaccine attitudes that, in turn, will be positively associated with intention to vaccinate one’s daughter (see Figure 1).

Subjective Norms and Interdependent Self-construal

Subjective norms refer to people’s beliefs about how influential others expect them to behave (with regard to specific behavioral actions) and their motivation to comply with those expectations (Lapinski & Rimal, 2005). As with attitudes, subjective norms have received investigation with respect to a wide range of health behaviors, from smoking (H.-R. Lee, et al., 2006; N. Rhodes & Ewoldsen, 2009), and sexual-risk behaviors (Bleakley, et al., 2011) (Manning, 2009), to cancer prevention (Smith-McLallen & Fishbein, 2008). Several studies have examined the role of subjective norms in determining parental acceptance of HPV vaccination (see Allen et al., 2010 for a review). However, these studies differ considerably in the operational definition of subjective norms (Allen et al., 2010), making it hard to generalize their findings.

In the study of normative behaviors, it has been shown that norms exert a greater behavioral impact when individuals feel a strong affinity with their reference group members for particular behaviors (Hogg & Reid, 2006; Lapinski & Rimal, 2005; Rimal & Real, 2005). It has been argued that to the extent people prioritize their social embeddedness over individual attributes in defining themselves, they should experience greater normative pressure to conform (Lapinski & Rimal, 2005). As articulated previously, one’s important social relationships (e.g. family, long-lasting work group) are integral components of an interdependent self (Markus & Kitayama, 1991). Several studies have found a positive association between interdependent self-construal and the strength of subjective norms from participants in collectivistic cultures (H.-R. Lee, et al., 2006; Park & Levine, 1999).

The present study likewise expects that more interdependently-oriented Korean American women would exhibit greater susceptibility to the expectations of others regarding HPV vaccination of their adolescent daughters. Consistent with IMBP (Fishbein & Cappella, 2006), which allows for the prediction of an indirect effect of interdependent self-construal on intention, we hypothesize a mediating role of subjective norms as seen in Figure 1.

H3: Subjective norms will mediate the relationship between interdependent self-construal and Korean American women’s behavioral intention to vaccinate their daughters.

That is, having an interdependent self-construal will be positively associated with conformity to subjective norms which in turn, will be positively associated with intention to have one’s daughter vaccinated against HPV.

English Linguistic Proficiency and Interdependent Self-Construal

English linguistic proficiency has been frequently noted as a crucial factor affecting health care access and general well-being of ethnic minorities in the United States (Derose, Bahney, Lurie, & Escarce, 2009). Non-English-speaking individuals report more difficulties in obtaining quality health information and health care than English-speaking individuals. People who are not fluent in English also usually experience higher level of anxiety and discomfort in their medical encounters (Derose, et al., 2009; Ngo-Metzger et al., 2003). As linguistic barriers are felt most keenly by non-English speaking recent immigrants, linguistic proficiency is widely used as a proxy for cultural adaption in the larger immigrant health literature (Schwartz, Unger, Zamboanga, & Szapocznik, 2010). However, despite the usefulness of linguistic proficiency in identifying at-risk or underserved population, it has been argued that this construct alone is not sufficient to capture the complexity of immigrants’ cultural adaption (Schwartz et al., 2010). There is a growing recognition that adaptation to U.S. culture may be a multidimensional phenomenon that takes place not only in behavior (e.g. becoming fluent in reading, listening, and speaking English), but also in cultural values, such as self-construal (Schwartz, et al., 2010; Schwartz et al., 2011; Unger, 2011). Using self-construal and individualism-collectivism to index cultural values, Schwartz et al (2011) found that immigrant students’ adaptation to behaviors and cultural values predicted differential health-related hazardous behaviors. This suggests that omitting cultural values and using behavioral measures alone, such as linguistic proficiency, might lead to an oversimplified or even erroneous picture of immigrant health.

Due to the dearth of research on HPV vaccination acceptance among non-English speaking ethnic minority parents, little is known whether limited English proficiency might affect parents’ attitudes, perceived norms, and intention to have their daughters vaccinated against HPV (Allen et al., 2010; Garcini, et al., 2012). However, in light of the projected growth of the Korean population in the United States and the research trajectory of immigrant health, it is important to ascertain whether interdependent self-construal, one commonly investigated cultural value, would make a unique contribution over and above English linguistic proficiency to the understanding of Korean American women’s HPV vaccination intention.

RQ: Will interdependent self-construal explain unique variance in Korean American women’s intention to vaccinate their adolescent daughters against HPV over and above English linguistic proficiency?

Methods

Participants

Participants in this study were combined from two data collection efforts as part of a larger quasi-experimental longitudinal study2. Eligible participants for the overall study were English speaking females between the ages of 25 to 45 who self-identified as Korean American and had not been diagnosed with cervical cancer. One hundred Korean American women were first recruited using a random digit dial (RDD) procedure from the Los Angeles area. Because these women tended to be fairly acculturated and given their English linguistic proficiency, we sought to increase the variability of our sample along the acculturation continuum by collecting an additional community sample without imposing the linguistic requirement. Of this community sample (N=83), 14 participants were approached in business areas (e.g. coffee shops, restaurants, and malls) and 69 through a snowball technique or word of mouth.

Participants in the RDD sample were interviewed using the Computer Assisted Telephone Interviewing (CATI) in English on self-construal as well as their attitudes, subjective norms, and intention with respect to HPV vaccination for daughters, amongst other constructs and facts related to cervical cancer prevention and detection. Eighty-two women who provided complete information on these constructs were included in the subsequent analysis. For the community sample, a single survey was put together with all aforementioned constructs of interest. These items were translated into Korean and then back-translated into English in order to ensure their fidelity to the original survey. Trained Korean speaking researchers administered the survey in paper-and-pencil format to all 83 respondents. The final sample for the current study consisted of 165 participants.

Participants had a median age of 38 years (M =36.7, SD = 6.1). Seven percent of the sample had less than a high school degree, 48.8% had some college or a bachelor’s degree, and 44.4% had more than a college degree. Approximately 71 percent of the participants were married, an additional 12.1% had a boyfriend, and 5.5% had a partner. About 43% of the participants reported having at least one daughter. A comparison of demographic characteristics between the RDD sample and the community sample revealed no significant difference in age and education. However, of those who provided complete information on household income for the last year, participants in the RDD sample earned significantly more than did participants in the community sample (p<.001). Lastly, about 70% of the participants were unaware of the causal link between HPV and cervical cancer, and almost half did not know how to prevent contracting HPV.

Measures

Interdependent self-construal

Six items from a previously validated 12-item scale were used to measure interdependent self-construal (Gudykunst & Lee, 2003; Gudykunst et al., 1996). Response ranged from 1 to 10, with 1=very strongly disagree and 10=very strongly agree. Example items include “I respect the decisions made by my group” and “I will sacrifice my self-interest for the benefits of my group”. The mean of the six items served as interdependent self-construal (Cronbach’s α =.82).

Attitudes

Attitudes toward having one’s adolescent daughter vaccinated against HPV were assessed using two 10-point Likert-type scales anchored at 1=not at all and 10=extremely. Participants were first prompted, “Now I would like you to imagine that you had a 13 year old daughter”. They were then asked “how important” and “how safe” it would be for their daughter to get the HPV vaccine.

Subjective norms

Normative beliefs and motivations to comply were both determined on a series of 10-point Likert-type scales, with 1 being not at all and 10 being a great deal. Beginning with the same prompt introduced above, normative beliefs were measured by requesting participants’ judgments about the extent to which four particular referents (i.e. husband, mother, other female relatives, and female friends) would approve of getting the participants’ 13 year old daughter vaccinated against HPV. Motivations to comply were assessed by having participants indicate the extent to which each referent’s opinion on health mattered to them. Then, normative belief items were multiplied with the corresponding ratings on motivation to comply, and the products were summed up across all types of referents to obtain subjective norms.

Behavioral intention

To assess intention, participants were asked, “Imagine you had a 13 year old daughter, how likely is it that you would have her vaccinated against HPV, on a scale from 1 to 10 where 1 means not at all likely and 10 means extremely likely?”

English linguistic proficiency

Linguistic proficiency was measured using a 12-item linguistic proficiency subscale (Marin & Gamba, 1996). The scale was originally developed to assess how well Hispanics speak, read, and write in Spanish and English, and has been adapted to ethnic populations, including Asian Americans (Jang, Kim, Chiriboga, & King-Kallimanis, 2007; Romero, Carvajal, Valle, & Orduña, 2007). For the RDD sample in this study, participants were first asked if they spoke another language besides English. Of those, 87.8% (N=72) were English-Korean bilinguals and subsequently rated their proficiency on both English and Korean linguistic domains over a series of 10-point Likert-type scales anchored at 1=very poorly and 10=very well. Example items include “How well do you speak English?” and “How well do you understand television programs in English?” For the community sample, all participants provided information regarding their proficiency on both linguistic domains. The Cronbach’s alphas for the subscales of English and Korean linguistic proficiency were both at .98 for the combined sample. However, the two subscales were significantly and negatively correlated, r=−.66, p < .001. Therefore, we included only the subscale on English linguistic proficiency for subsequent analysis. English monolingual participants were given a value of 10 on this subscale to reflect their linguistic proficiency.

Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 19.0. Table 1 presents descriptive information for the main variables of interest. To test the direct (H1) and indirect effect of interdependent self-construal through attitudes (H2) and subjective norms (H3), we carried out a mediation analysis via Hayes’s (2012) PROCESS procedure using 10,000 bootstrapping resamples. This procedure enabled us to simultaneously examine the mediating roles of attitudes and subjective norms in the same model, and to statistically assess their relative influence in mediating the relationship between interdependent self-construal and intention. To explore our research question, English linguistic proficiency was entered as a covariate in each regression step of the mediation model. All continuous variables were standardized to a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. The alpha level was determined at .05 a priori. Our mediation model also controlled for educational attainment, whether or not participants reported having at least one daughter, the type of language used in survey administration, and knowledge about HPV, because these variables might relate to the behavioral intention in question. However, none of them was significantly associated with any dependent variable in any step of the mediation analysis. Thus, Table 2 includes only the major predictors of interest for the sake of clarity and parsimony.

Table 1.

Summary of Intercorrelations, Means, and Standard Deviations for Scores on Attitudes, Subjective Norms, Behavioral Intention, Interdependent Self-Construal, and English Linguistic Proficiency (N=165)

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude - Importance (1) | ---- | 8.06 | 2.24 | ||||

| Attitudes - Safety (2) | .41** | ---- | 6.86 | 2.53 | |||

| Subjective Norms (3) | .27** | .24** | ---- | 183.03 | 106.79 | ||

| Behavioral Intention (4) | .61** | .32** | .39** | ---- | 7.22 | 2.79 | |

| Self- Construal (5) | .01 | .22** | .18* | .05 | ---- | 7.45 | 1.34 |

| Linguistic Proficiency (6) | −.08 | .00 | .22** | −.07 | .23** | 6.99 | 2.61 |

Note. For all scales, higher scores are indicative of more extreme responding in the direction of the construct assessed.

p<0.05.

p<0.01.

Table 2.

Effects of Interdependent Self Construal, Attitudes, Subjective Norms, and English Linguistic Proficiency (N=117a)

| Behavioral Intention |

Attitude - Importance |

Attitude - Safety |

Subjective Norms |

Behavioral Intention (Full Mediation Model) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self- Construal |

.19* | .07 | .28** | .21* | .10 |

| Attitude - Importance |

-- | -- | -- | -- | .42*** |

| Attitude- Safety |

-- | -- | -- | -- | .05 |

| Subjective Norms |

-- | -- | -- | -- | .25** |

| Linguistic Proficiency |

.05 | −.03 | .04 | .12 | .03 |

| R2 | .11 | .09 | .11 | .16 | .45 |

Note: Standard beta coefficients from mediation analysis are reported. All analyses controlled for a) education, b) whether or not participants reported having at least one daughter, c) participants’ difference in language used in survey administration between the RDD and the community sample, and d) HPV knowledge.

N represents the number of participants who provided valid responses to questions regarding all four reference groups.

p <.05.

p <.01.

p <.001

Results

Our first hypothesis (H1) posited a positive association between the strength of interdependent self-construal and Korean American women’s intention to vaccinate their adolescent daughters against HPV. H1 was supported. The regression model testing this hypothesis was marginally significant and explained 11% of the variance in intention, F (7, 109) = 2.02, p <.06. As shown in Table 2, interdependent self-construal was significantly and positively associated with intention, β = .19, p < .03, after accounting for participants’ English linguistic proficiency and the control variables (educational attainment, whether or not participants reported having at least one daughter, the type of language used in survey administration, and HPV knowledge).

Our second hypothesis predicted an indirect effect of interdependent self-construal on intention via Korean American women’s attitudes toward the importance (Attitude -Importance; H2a) and safety (Attitude-Safety; H2b) of HPV vaccination for their adolescent daughters. This involved testing paths from interdependent self-construal to attitudes and from attitudes to intention. As seen in Table 2, regressing attitude-importance on interdependent self-construal did not yield a statistically significant association between the two variables. Nevertheless, the full mediation model including all hypothesized mediating variables showed that attitude-importance was significantly and positively associated with intention. That is, in our analysis the attitude about the vaccination’s importance impacted intention, but did not act as a mediator between interdependent self-construal and intention. H2a was not supported. On the other hand, the attitude-safety regression model showed that interdependent self-construal was significantly and positively associated with attitude-safety, β = .28, p < .003. However, our full mediation model failed to detect a significant effect of attitude-safety on intention. Taken together, this indicates that participants’ attitude about the safety of HPV vaccination did not mediate the influence of interdependent self-construal on intention. H2b was not supported.

We followed the same procedure to test our third hypothesis that proposed a mediating role of subjective norms. As shown in Table 2, the subjective norms regression model revealed interdependent self-construal as a significant predictor, β = .21, p < .03. Next, when entered together with interdependent self-construal and attitudes in the full mediation model, subjective norms was found to have a significant and positive association with intention, β = .25, p <.01. Moreover, since interdependent self-construal was no longer a significant predictor of intention in the full mediation model, it is safe to conclude that subjective norms did mediate the effect of interdependent self-construal on intention. H3 was supported.

Furthermore, compared with the regression model testing H1, where only interdependent self-construal was included as the predictor, the full model was able to explain 45% of the variance in intention, F (10, 106) = 8.85, p <.000, indicating that Korean American women’s intention might be best predicted by including both cultural and behavioral determinants. Moreover, a closer look at the coefficients of the full mediation model suggests that attitude about the importance of HPV vaccination (β = .42) appeared to be a more influential determinant for intention than subjective norms (β = .25). Table 3 presents the direct and indirect effect of interdependent self-construal, attitudes, and subjective norms on intention. In summary, results from testing the hypotheses indicated that the relationship between interdependent self-construal and intention was mediated by subjective norms, not attitudes.

Table 3.

Total, Direct, and Indirect Effects of Interdependent Self Construal, Attitudes, and Subjective Norms on Behavioral Intention (N=117a)

| Mean Effect | SE | Biased-corrected 95% CI |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | |||

| Total effect | ||||

| Self-Construal | .195 | .087 | .023 | .367 |

| Direct effect | ||||

| Self-Construal | .096 | .073 | −.050 | .241 |

| Indirect effect via | ||||

| Attitude-Importance | .031 | .051 | −.076 | .127 |

| Attitude-Safety | .014 | .023 | −.026 | .070 |

| Subjective Norms | .055 | .030 | .011 | .132 |

N represents the number of participants who provided valid responses to questions regarding all four reference groups.

Finally, our research question pertained to whether interdependent self-construal would have unique impact on intention after controlling for participants’ English linguistic proficiency. This question was explored by examining the coefficients and critical values of interdependent self-construal in our mediation analysis, where English linguistic proficiency was entered as a covariate in every regression step. As shown in Table 2, the attitude-safety and subjective norm regression models both suggested that, adjusting for English linguistic proficiency, interdependent self-construal was significantly related to the attitude about the safety of HPV vaccination and subjective norms. Subjective norms in turn, as shown in the full mediation model, predicted intention. English linguistic proficiency, on the other hand, was not significantly associated with attitudes, subjective norms, or intention.

Discussion

The primary purpose of this study was to examine the mechanisms by which interdependent self-construal, attitudes, and subjective norms affect Korean American women’s intention to vaccinate their adolescent daughters against HPV. We found a significant and positive association between the strength of interdependent self-construal and intention to vaccinate their daughters against HPV, supporting H1. Interdependent self-construal also had an indirect effect through subjective norms on intention, supporting H3. Although we were not able to substantiate the mediating role of attitudes about the importance (H2a) and safety (H2b) of HPV vaccination, our full mediation model revealed that participants’ attitudes about the importance of vaccination was one of the two significant predictors of intention to vaccinate and carried greater influence than subjective norms. Finally, we found that interdependent self-construal made a unique contribution in explaining participants’ vaccination intention over and above their English linguistic proficiency; which in itself was not a significant predictor for any of the main constructs examined.

Interdependent self-construal and health decision-making

We found that Korean American women holding a strong interdependent self-construal were more likely to have their adolescent daughters vaccinated against HPV. Joining the call for a more nuanced understanding of culture and health, our study thus underscores the importance and prospect for health communication researchers and practitioners to unpack the label of “cultural influence” by looking at specific components of culture, which, in our case, involves individuals’ divergent views of self.

Interdependent self-construal, attitudes, and subjective norms

It has been emphasized that the need for health communication research to identify individuals’ self-construal is not to perpetuate cultural stereotypes, but to understand the cultural underpinning in which certain health beliefs are crystallized, maintained, and transformed (Murphy, 1998). This is particularly important for behavioral campaigns and interventions because it is the comprehensive understanding of underlying health beliefs that closely impact campaign effectiveness and program delivery (Fishbein & Cappella, 2006).

In the current study, regardless of individual differences in interdependent self-construal, Korean American women were more likely to vaccinate their daughters against HPV if they thought more positively about the importance of the vaccination and were more susceptible to the normative influence of their family and close friends. Nevertheless, a mediating role of subjective norms implies that Korean American women with an elaborated interdependent view of self were more likely to perceive the expectations of their family and close friends regarding vaccinating an adolescent daughter against HPV; and they were more likely to conform to these expectations. This latter finding is consistent with the observations previously reported in both self-construal and norm literature, suggesting that norms affect behaviors to a greater extent for interdependently-oriented individuals because of their conception of self being an integral component of social context to which these individuals strive to connect and assimilate (Hogg & Reid, 2006; Lapinski & Rimal, 2005; Markus & Kitayama, 1991). More specifically, people endorsing an interdependent view of self tend to give more weights to subjective norms than to attitudes in guiding their behaviors (Bagozzi, Wong, Abe, & Bergami, 2000; Cross, et al., 2011; Park & Levine, 1999; Triandis, 1989).

Knowledge regarding the relationship between interdependent self-construal, attitudes, and subjective norms is critical to the decisions concerning campaign message design to spur HPV vaccination in Korean American communities. For example, because attitudes about the importance of HPV vaccination and the subjective norms were significant predictors for intention, campaign messages targeting either or both constructs may bear fruit. For individuals with stronger interdependent self-orientations, it would be prudent to design HPV vaccine campaign messages that modify not only the attitudes and beliefs of target population, but also their family and close friends whose opinions carry a great deal of influence.

Given that HPV is sexually transmitted, prior research has shown that promoting the HPV vaccine presents unique challenges (Darden et al., 2013; Trim et al., 2012). Addressing this issue in Korean American communities is particularly challenging, as traditional Korean culture is known for its taboo against openly discussing sex-related topics (Z.N. Lee, 1999; Youn, 2001). Thus, campaigners may benefit from incorporating culturally-sensitive ways to encourage women’s health-related conversation within Korean American community, which can eventually lead to favorable changes in knowledge and beliefs. This approach might be particularly effective for interdependently-oriented individuals given their strong adherence to subjective norms.

An additional strategy to promote HPV vaccination among Korean Americans holding a strong interdependent view of self may be to target their attitude about the safety of the vaccination. A recent study by Darden et al (2013) found that safety concern and side effects rose drastically from 4.5% in 2008 to 16.4% in 2010 as a main reason for parents’ lack of intention to vaccinate their female teens against HPV. In our study, a post-hoc paired-sample t-test was conducted to investigate the relative salience of attitudes about the importance and safety of HPV vaccination among all participants. Results of this analysis showed that Korean American women in our sample had a more favorable attitude toward the vaccination’s importance than its safety, t (148) = 6.03, p <.001, suggesting that more work needs to be done in allaying the safety concerns of the target population.

Looking beyond linguistic proficiency

Finally, the current study observed the behavioral impact of interdependent self-construal over and above participants’ English linguistic proficiency. Previous studies have repeatedly shown that racial/ethnic minority populations unfamiliar with the English language encounter more obstacles in accessing health information and health service (Derose et al., 2009; Ngo-Metzger et al, 2003). However, English linguistic proficiency did not predict attitudes, subjective norms, or intention regarding vaccinating adolescent daughters for our sample of Korean American women. Our study thus adds to a growing body of evidence (see Schwartz et al., 2010; Kreuter & McClure, 2004) suggesting that linguistic strategies alone might be insufficient and even inappropriate without considering more nuanced levels of cultural characteristics of a target population, such as their predominant self-construal. Our study would suggest for instance that even when delivered in Korean, a message seeking to modify parents’ attitudes regarding HPV vaccination might fail if the intended audience is more interdependently-oriented and, as a result, are less responsive to messages that propose individual level behavioral change without taking the social context into account.

Limitations

The current study has various limitations. First, our participants were Korean American women between the ages of 25–45 recruited from the greater Los Angeles area. As a result, our findings might not generalize to Korean Americans in other age groups or in different geographic locations. Second, we noted that our sample consisted of highly educated individuals, with over 90 percent having attended at least some college. Future research should attempt to include less educated Korean American women as well to increase generalizability. Third, because we didn’t collect information on insurance for the community sample, we were unable to assess the impact of health care coverage on Korean American women’s intention to vaccinate their daughters. Given the well-documented role of insurance in accessing health care (Yoo & Wood, 2013), we encourage future research to consider the inclusion of insurance status and other structural constraints, especially since physician recommendation has been frequently associated with parental intention to vaccinate (Darden et al., 2013; Trim et al., 2012). Last, a concern for environmental barriers suggests the shortcoming of using intention instead of actual behavior in this study. Despite the extensive evidence indicating the high predictability of intention for future behavior (Armitage & Conner, 2000, 2001), this construct remains an imperfect proxy and is under the influence of a variety of environmental forces (Fishbein & Cappella, 2006). With HPV vaccines becoming increasingly available and accessible, health communication researchers and professionals should collect information on actual vaccination behavior so that the mechanisms by which cultural and behavioral determinants affect the behavior in question can be better modeled.

Conclusion

Women from racial and ethnic minority groups in the United States are disproportionately affected by cervical cancer. HPV vaccines appear to be a promising venue to reduce these persistent disparities by preventing the most common HPV strains known to cause 70% of cervical cancer (CDC, 2012a). What is lacking is a better understanding of how cultural and behavioral factors influence parental intention to vaccinate their adolescent daughters against HPV. The current study bridges this gap by identifying the mechanisms through which interdependent self-construal, attitudes, and subjective norms impact Korean American mothers’ intention to vaccinate their adolescent daughters. This study makes timely and crucial contribution to health disparity literature, considering that Korean Americans, as one of the fastest growing U.S. Asian subpopulations, have had alarmingly high cervical cancer mortality and incidence in certain states, such as California (McCracken, et al., 2007). Our findings suggest that self-construal as an individual-level approach to theorize about cross- and within-cultural difference holds promise for health communication research to not only uncover the rich variance of health-related beliefs among individuals of shared cultural descent, but also to understand the context in which these beliefs are embedded. For public health efforts, obtaining such a delicate understanding represents a fruitful first step toward crafting culturally sensitive and innovative strategies to eliminate cervical cancer disparities among not only Korean Americans, but also underserved minorities more generally.

Acknowledgments

This paper was supported by the National Cancer Institute for TRO1-Transforming Cancer Knowledge, Attitudes and Behavior through Narrative awarded to the University of Southern California (R01CA144052 - Murphy/Baezconde-Garbanati). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent official views of the NCI or of the National Institutes of Health. The authors would like to thank the following individuals for their contributions to the work: Dr. Meghan Moran, Dr. Lauren B. Frank and Paula Amezola.

Footnotes

The current study measured both independent and interdependent self-construal during data collection. However, because the two types of self-construal were moderately and positively correlated for our sample (r=.48, p<.000), and in light of prior literature, we decided to focus on only interdependent self-construal in this manuscript.

This study is part of a larger project related to testing a narrative based cervical cancer intervention that collected data at baseline, 2-week posttest, and 6-month follow-up. In addition to Korean American women, this larger project included European American, Mexican American, and African American women.

Reference

- Ajzen I. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In: Kuhl J, Beckman J, editors. Action-control: From cognition to behavior. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 1985. pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991;50(2):179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Attitudinal and normative variables as predictors of specific behaviors. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1973;27(1):41–57. [Google Scholar]

- Allen JD, Coronado GD, Williams RS, Glenn B, Escoffery C, Fernandez M, Mullen PD. A systematic review of measures used in studies of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine acceptability. Vaccine. 2010;28(24):4027–4037. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.03.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armitage CJ, Conner M. Social cognition models and health behaviour: A structured review. Psychology & Health. 2000;15(2):173. [Google Scholar]

- Armitage CJ, Conner M. Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analytic review. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2001;40(4):471–499. doi: 10.1348/014466601164939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi RP, Wong N, Abe S, Bergami M. Cultural and situational contingencies and the theory of reasoned action: Application to fast food restaurant consumption. Journal of Consumer Psychology. 2000;9(2):97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Blackhall LJ, Frank G, Murphy ST, Michel V, Palmer JM, Azen SP. Ethnicity and attitudes towards life sustaining technology. Social Science and Medicine. 1999;48(12):1779–1789. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00077-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackhall LJ, Murphy ST, Frank G, Michel V, Azen S. Ethnicity and attitudes toward patient autonomy. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1995;274(10):820–825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleakley A, Hennessy M, Fishbein M, Jordan A. Using the integrative model to explain how exposure to sexual media content influences adolescent sexual behavior. Health Education & Behavior. 2011;38(5):530–540. doi: 10.1177/1090198110385775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC health disparities and inequalities report - United States, 2011. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2011;Vol. 60(Suppl):1–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Epidemiology and prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases. (12 ed.) 2012a [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Genital HPV infection: Fact sheet. 2012b from http://www.cdc.gov/std/HPV/STDFact-HPV.htm#common.

- Cross SE, Hardin EE, Gercek-Swing B. The what, how, why, and where of self-construal. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2011;15(2):142–179. doi: 10.1177/1088868310373752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darden PM, Thompson DM, Roberts JR, Hale JJ, Pope C, Naifeh M, Jacobson RM. Reasons for not vaccinating adolescents: National Immunization Survey of Teens, 2008–2010. Pediatrics. 2013;131(4):645–651. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darden PM, Thompson DM, Roberts JR, Hale JJ, Pope C, Naifeh M, Jacobson RM. Reasons for not vaccinating adolescents: National Immunization Survey of Teens, 2008–2010. Pediatrics. 2013;131(4):645–651. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derose KP, Bahney BW, Lurie N, Escarce JJ. Review: Immigrants and health care access, quality, and cost. Medical Care Research and Review. 2009;66(4):355–408. doi: 10.1177/1077558708330425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang CY, Ma GX, Tan Y. Overcoming barriers to cervical cancer screening among Asian American women. The North American Journal of Medical Sciences. 2011;4(2):77–83. doi: 10.7156/v4i2p077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, Cappella JN. The role of theory in developing effective health communications. Journal of Communication. 2006;56:S1–S17. [Google Scholar]

- Garcini LM, Galvan T, Barnack-Tavlaris JL. The study of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine uptake from a parental perspective: A systematic review of observational studies in the United States. Vaccine. 2012;30(31):4588–4595. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.04.096. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.04.096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudykunst WB, Lee CM. Assessing the validity of self construal scales. Human Communication Research. 2003;29(2):253–274. [Google Scholar]

- Gudykunst WB, Matsumoto Y, Ting-Toomey S, Nishida T, Kim K, Heyman SAM. The influence of cultural individualism-collectivism, self construals, and individual values on communication styles across cultures. Human Communication Research. 1996;22(4):510–543. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling [White paper] 2012 Retrieved from http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf.

- Hogg MA, Reid SA. Social identity, self-categorization, and the communication of group norms. Communication Theory. 2006;16(1):7–30. [Google Scholar]

- Im E-O, Lee EO, Park YS, Salazar MK. Korean women’s breast cancer experience. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2002;24(7):751–771. doi: 10.1177/019394502762476960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang Y, Kim G, Chiriboga D, King-Kallimanis B. A bidimensional model of acculturation for Korean American older adults. Journal of Aging Studies. 2007;21(3):267–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2006.10.004. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagawa Singer M. Applying the concept of culture to reduce health disparities through health behavior research. Preventive Medicine. 2012;55(5):356–361. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.02.011. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kam J, Matsunaga M, Hecht M, Ndiaye K. Extending the theory of planned behavior to predict alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana use among youth of Mexican heritage. Prevention Science. 2009;10(1):41–53. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0110-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Schulenberg JE, O'Malley PM, Johnston LD, Bachman JG, Li G, Hasin D. Birth cohort effects on adolescent alcohol use: The influence of social norms from 1976 to 2007. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69(12):1304–1313. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter MW, McClure SM. The role of culture in health communication. Annual Review of Public Health. 2004;25(1):439–455. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.101802.123000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapinski MK, Rimal RN. An explication of social norms. Communication Theory. 2005;15(2):127–147. [Google Scholar]

- Lee EE, Fogg L, Menon U. Knowledge and beliefs related to cervical cancer and screening among Korean American women. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2008;30(8):960–974. doi: 10.1177/0193945908319250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H-R, Ebesu Hubbard A, O'Riordan CK, Kim M-S. Incorporating culture into the theory of planned behavior: Predicting smoking cessation intentions among college students. Asian Journal of Communication. 2006;16(3):315–332. [Google Scholar]

- Lee HY, Ju E, Vang PD, Lundquist M. Breast and cervical cancer screening among Asian American women and Latinas: Does race/ethnicity matter? J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2010;19(10):1877–1884. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MC. Knowledge, barriers, and motivators related to cervical cancer screening among Korean-American women: A focus group approach. Cancer Nursing. 2000;23(3):168–175. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200006000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y-S, Hofstetter CR, Irvin VL, Kang S, Chhay D, Reyes WD, Hovell MF. Korean American women's preventive health care practices: Stratified samples in California, USA. Health Care for Women International. 2012;33(5):422–439. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2011.603869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y-S, Roh S, Vang S, Jin SW. The contribution of culture to Korean American women's cervical cancer screening behavior: the critical role of prevention orientation. Ethn Dis. 2011;21(4):399–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Z-N. Korean culture and sense of Shame. Transcultural Psychiatry. 1999;36(2):181–194. [Google Scholar]

- Manning M. The effects of subjective norms on behaviour in the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analysis. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2009;48(4):649–705. doi: 10.1348/014466608X393136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin G, Gamba RJ. A new measurement of acculturation for Hispanics: The bidimensional acculturation scale for Hispanics (BAS) Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1996;18(3):297–316. [Google Scholar]

- Markus HR, Kitayama S. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review. 1991;98(2):224–253. [Google Scholar]

- McCracken M, Olsen M, Chen MS, Jr., Jemal A, Thun M, Cokkinides V, Ward E. Cancer incidence, mortality, and associated risk factors among Asian Americans of Chinese, Filipino, Vietnamese, Korean, and Japanese ethnicities. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57(4):190–205. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.4.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy ST. A mile away and a world apart: The impact of independent and interdependent views of the self on US-Mexican communications. In: Power J, Byrd T, editors. Health care communication on the US/Mexico border. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1998. pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines. 2011 from http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet/prevention/HPV-vaccine.

- Ngo-Metzger Q, Massagli MP, Clarridge BR, Manocchia M, Davis RB, Iezzoni LI, Phillips RS. Linguistic and cultural barriers to care. Journal of general internal medicine. 2003;18(1):44–52. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20205.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oetzel J, De Vargas F, Ginossar T, Sanchez C. Hispanic women's preferences for breast health Information: Subjective cultural influences on source, message, and channel. Health Communication. 2007;21(3):223–233. doi: 10.1080/10410230701307550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh A, Shaikh A, Waters E, Atienza A, Moser RP, Perna F. Health disparities in awareness of physical activity and cancer prevention: Findings from the National Cancer Institute's 2007 Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) Journal of health communication. 2010;15:60–77. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.522694. [Article] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park HS, Levine TR. The theory of reasoned action and self-construal: Evidence from three cultures. Communication Monographs. 1999;66(3):199–218. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes F, Stein J, Fishbein M, Goldstein R, Rotheram-Borus M. Using theory to understand how interventions work: Project RESPECT, condom use, and the integrative model. AIDS and Behavior. 2007;11(3):393–407. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9208-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes N, Ewoldsen DR. Attitude and norm accessibility and cigarette smoking. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2009;39(10):2355–2372. [Google Scholar]

- Rimal RN, Real K. How behaviors are influenced by perceived norms. Communication Research. 2005;32(3):389–414. [Google Scholar]

- Romero AJ, Carvajal SC, Valle F, Orduña M. Adolescent bicultural stress and its impact on mental well-being among Latinos, Asian Americans, and European Americans. Journal of Community Psychology. 2007;35(4):519–534. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson J, Witte K, Morrison K, Liu W-Y, Hubbell AP, Murray-Johnson L. Addressing cultural orientations in fear appeals: Promoting AIDS-protective behaviors among Mexican immigrant and African American adolescents and American and Taiwanese college students. Journal of Health Communication. 2001;6(4):335–358. doi: 10.1080/108107301317140823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Zamboanga BL, Szapocznik J. Rethinking the concept of acculturation: Implications for theory and research. American Psychologist. 2010;65(4):237–251. doi: 10.1037/a0019330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Weisskirch RS, Zamboanga BL, Castillo LG, Ham LS, Huynh Q-L, Cano MA. Journal of Counseling Psychology. Vol. 58. United States: American Psychological Association; 2011. Dimensions of acculturation: Associations with health risk behaviors among college students from immigrant families; pp. 27–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman DK, Uskul AK, Updegraff JA. The role of the self in responses to health communications: A cultural perspective. Self and Identity. 2011;10(3):284–294. doi: 10.1080/15298868.2010.517029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-McLallen A, Fishbein M. Predictors of intentions to perform six cancer-related behaviours: Roles for injunctive and descriptive norms. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2008;13(4):389–401. doi: 10.1080/13548500701842933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triandis HC. The self and social behavior in differing cultural contexts. Psychological Review. 1989;96(3):506. [Google Scholar]

- Trim K, Nagji N, Elit L, Roy K. Parental Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behaviours towards Human Papillomavirus Vaccination for Their Children: A Systematic Review from 2001 to 2011. Obstetrics and Gynecology International, 2012. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/921236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. The Asian Population: 2010. 2010 from http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-11.pdf.

- Unger JB. Cultural identity and public health. In: Schwartz SJ, Luyckx K, Vignoles VL, editors. Handbook of Identity Theory and Research. Vol. 2. New York: Springer New York; 2011. pp. 811–825. [Google Scholar]

- Uskul AK, Oyserman D. When message-frame fits salient cultural-frame, messages feel more persuasive. Psychology & Health. 2010;25(3):321–337. doi: 10.1080/08870440902759156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts L, Joseph N, Velazquez A, Gonzalez M, Munro E, Muzikansky A, del Carmen MG. Understanding barriers to cervical cancer screening among Hispanic women. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2009;201(2) doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.05.014. 199.e191-199.e198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo G, Wood S. Challenges and opportunities for improving health in the Korean American community. In: Yoo GJ, Le M-N, Oda AY, editors. Handbook of Asian American Health. New York: Springer; 2013. pp. 73–85. [Google Scholar]

- Youn G. Perceptions of peer sexual activities in Korean Adolescents. The Journal of Sex Research. 2001;38(4):352–360. [Google Scholar]

- Youn G. Perceptions of peer sexual activities in Korean Adolescents. The Journal of Sex Research. 2001;38(4):352–360. [Google Scholar]

- Yu N, Shen F. Benefits for me or risks for others: A cross-culture investigation of the effects of message frames and cultural appeals. Health Communication. 2012;28(2):133–145. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2012.662147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]