Abstract

Bicycle sharing systems are increasingly popular around the world and have the potential to increase the visibility of people cycling in everyday clothing. This may in turn help normalise the image of cycling, and reduce perceptions that cycling is ‘risky’ or ‘only for sporty people’. This paper sought to compare the use of specialist cycling clothing between users of the London bicycle sharing system (LBSS) and cyclists using personal bicycles. To do this, we observed 3594 people on bicycles at 35 randomly-selected locations across central and inner London. The 592 LBSS users were much less likely to wear helmets (16% vs. 64% among personal-bicycle cyclists), high-visibility clothes (11% vs. 35%) and sports clothes (2% vs. 25%). In total, 79% of LBSS users wore none of these types of specialist cycling clothing, as compared to only 30% of personal-bicycle cyclists. This was true of male and female LBSS cyclists alike (all p>0.25 for interaction). We conclude that bicycle sharing systems may not only encourage cycling directly, by providing bicycles to rent, but also indirectly, by increasing the number and diversity of cycling ‘role models’ visible.

Keywords: Cycling, Bicycle sharing systems, Helmets, Perceptions, Gender

Highlights

-

•

Many potential cyclists are put off as they perceive cycling as too risky or sporty.

-

•

This may be reinforced if existing cyclists are seen to wear safety or sports clothes.

-

•

Bicycle sharing systems (BSS) may encourage cycling in everyday clothing.

-

•

London BSS users are less likely to wear helmets, high-viz or sports clothes.

-

•

BSS have the potential to normalise the image of cycling, and so promote cycling.

1. Introduction

Promoting a shift from motor vehicle travel to cycling is expected to confer substantial health and environmental benefits (de Hartog et al., 2010, Department for Transport, 2011, Maizlish et al., 2013). Nevertheless, cycling remains rare in many settings. For example, only 2% of trips in London are currently cycled, even though an estimated 23% of trips could reasonably be made by bicycle (Transport for London, 2010). One of the most common reasons people give for not cycling is its perceived risk. For example, a recent survey of UK adults found that 86% selected cycling as the mode most at risk of traffic accidents, as opposed to 2–7% for other modes (Thornton et al., 2010). Some current or potential cyclists may also be put off by the perception that cycling is exclusively an activity for ‘sporty’ people, an identity that they may feel unwilling or unable to embody (Aldred, 2012b, Steinbach et al., 2011). For example, one recent qualitative study described how regular bicycle users distanced themselves from “these hard core sporting cyclists” in ways that seemed to reflect anxieties about being seen as a failure or an imposter if they and their bodies were to be judged against the sporty ideal (Aldred, 2012b).

It is plausible that these negative perceptions are reinforced to the extent that people see existing cyclists wearing ‘safety’ clothing (e.g. helmets or high-visibility clothes) or ‘sporty’ clothing (e.g. Lycra). In addition, seeing many existing cyclists wearing such clothing has been reported to discourage uptake of cycling by indicating the apparent effort involved (e.g. having to remember your helmet, having to change your clothes at work) (Green et al., 2012). Finally, the perceived need for such clothing renders people on a bicycle socially visible as ‘cyclists’ in a way which is not true for other modes (Aldred, 2012b, Horton, 2007, Steinbach et al., 2011), and which may be particularly off-putting for women (Steinbach et al., 2011). By contrast, very few people on bicycles wear helmets or other ‘cycling’ clothes in high-cycling settings like the Netherlands, reflecting the status of cycling as an accepted, normal means of making everyday journeys (Ministry of Transport, 2009, Villamor et al., 2008).

One potential way in which cycling may become normalised in low-cycling settings is through the introduction of bicycle sharing systems (BSS). Increasingly popular around the world (Shaheen et al., 2012), BSS allow short-term bicycle rental between docking stations, and so make cycling a form of public transport. Such schemes have the potential to confer important health benefits (Rojas-Rueda et al., 2011, Woodcock et al., 2014), although (at least in the short term) their environmental benefits may be limited by the typically small percentage of users who would otherwise have travelled by private motorised vehicle (Fishman et al., 2013). Trips on BSS bicycles are often both spontaneous and short, and qualitative research from Australia suggests that many potential users may therefore not have a helmet with them and may not feel that their trip would make them perspire (plausibly removing any perceived need for sports clothes) (Fishman et al., 2012). One observational American study has examined this issue quantitatively, and reported that BSS cyclists did indeed wear helmets less often than those riding personal bicycles (19% vs. 51%) (Fischer et al., 2012).

These previous studies therefore suggest the potential for BSS to increase the visibility of people cycling in ‘ordinary’ clothing, and so perhaps to normalise the image of cycling and reduce some reported barriers to cycling uptake. In this paper we aimed to examine whether users of the London bicycle sharing system (LBSS) were less likely than personal-bicycle cyclists to be wearing clothing that signalled that they were ‘cyclists’ rather than just ‘people cycling’. In doing so we sought to build upon the previous American study by examining not only the use of helmets, but also use of high-visibility clothes and sports clothes.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. The London bicycle sharing system

The London bicycle sharing system (LBSS) was launched in July 2010, and operates 24 h a day 365 days a year. The scheme currently comprises 8000 bicycles located at 571 docking stations across 65 km2 of central and inner London. To hire a bicycle, users can either register online for an access key (‘registered use’), or else pay by credit/debit card at docking stations (‘casual use’, available since December 2010). Users must be at least 18 years old to register and at least 14 years old to use the bicycles.

2.2. Data collection

Between 09/04/2013 and 15/04/2013, 35 LBSS docking stations were selected at random from across central and inner London (see Supplementary material for map). Trained observers visited these docking stations at various times between 6.30 am and 7 pm, with observation times being divided a priori into weekday peak periods (6.30–9.30 am and 4–7 pm, N=12); weekday inter-peak periods (9.30 am to 4 pm, N=13); and weekend periods (N=10). The mean temperature during observation periods was 9 °C (range 4–17 °C), with roughly equal numbers of rainy, cloudy and sunny periods.

At each selected site, an observer stood within sight of the docking station at a position which maximised the volume of bicycle traffic visible. The observer then used a standardised form to record the characteristics of bicycles passing in either direction over a period of 30–45 min. Two observers were used at some sites with high numbers of bicycles, with the two observers covering traffic in different directions. Observers recorded the cyclist’s gender plus yes/no responses to whether the cyclist was using (i) an LBSS bicycle, (ii) a helmet, (iii) high-visibility clothes (defined as fluorescent or reflective clothes, e.g. fluorescent or reflective jackets, bag covers or strips around the waist or shoulder), and (iv) cycling ‘sports’ clothes (defined as spandex shorts, leggings or tops, or as non-spandex shorts which were above the knee and appeared to be designed for sport). Observers used their judgement in categorising marginal cases, e.g. in deciding whether a given pair of shorts was designed for ‘sport’. Inter-rater reliability (N=65 bicycles) ranged from 0.88 (for sports clothes) to 1 (for LBSS bicycle status). Observers excluded individuals pushing a bicycle, riding as a passenger or appearing younger than 14 years (the minimum age when LBSS use is permitted). Cyclists noted to have passed the observation point multiple times were only recorded once. Ethical approval was granted by the LSHTM research ethics committee (reference 6384).

2.3. Data analysis

We present both raw percentages and multivariable logistic regression analyses. To account for differences between sampling sites, we fitted two-level random intercept models in these multivariable analyses, with bicycles nested within sites (equation in Supplementary material). We excluded bicycles which passed before full data could be recorded (2%). All analyses were conducted in Stata 12.1.

3. Results

Across 19.75 h of observation, full data was recorded on 3594 people on bicycles. Of these, 880 (24%) were females and 592 (16%) were using LBSS bicycles. Helmets were worn by 2014 (56%) of the cyclists, high-visibility clothes by 1117 (31%) and sports clothes by 752 (21%). There were positive associations between wearing all three types of cycling clothing (Pearson correlations 0.41 between helmet and high-visibility, 0.34 between helmet and sports clothes and 0.19 between high-visibility and sports clothes, all p<0.001).

Cyclists riding personal bicycles were three to four times more likely to wear helmets or high-visibility clothes, and ten times more likely to wear sports clothes (Table 1). Overall 70% of personal-bicycle cyclists wore at least one of these types of clothing, as opposed to 21% of LBSS cyclists – or, conversely, only 30% of personal-bicycle cyclists wore largely ‘everyday’ clothing, as compared to 79% of LBSS cyclists. These marked differences persisted in multivariable models, with other independent predictors including an association between male gender and wearing sports clothes, and an association between weekday peak periods and wearing all types of cycling clothing (Table 1). These findings were similar in sensitivity analyses that excluded the 382 bicycles observed at two sites where the majority of the cycling appeared to be for recreation rather than transport (see Supplementary material).

Table 1.

Predictors of wearing different types of cycling clothing (N=3594 bicycles).

|

Wearing a helmet |

Wearing high-visibility clothes |

Wearing sports clothes |

Wearing any cycling clothing |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | Adjusted OR (95%CI) | % | Adjusted OR (95%CI) | % | Adjusted OR (95%CI) | % | Adjusted OR (95%CI) | ||

| Bicycle | LBSS (N=592) | 16 | 1 | 11 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 21 | 1 |

| Personal (N=3002) | 64 | 9.52 (7.34, 12.35) | 35 | 3.41 (2.56, 4.55) | 25 | 18.54 (9.76, 35.24) | 70 | 8.94 (7.00, 11.43) | |

| Gender | Male (N=2714) | 56 | 1 | 31 | 1 | 24 | 1 | 63 | 1 |

| Female (N=880) | 57 | 1.20 (1.00, 1.45) | 32 | 1.11 (0.93, 1.33) | 11 | 0.38 (0.30, 0.49) | 60 | 0.99 (0.82, 1.19) | |

| Time period | Weekday peak (N=2293) | 69 | 1 | 41 | 1 | 26 | 1 | 75 | 1 |

| Weekday inter-peak (N=582) | 41 | 0.31 (0.18, 0.54) | 21 | 0.45 (0.30, 0.68) | 12 | 0.33 (0.18, 0.60) | 50 | 0.31 (0.18, 0.55) | |

| Weekend (N=719) | 28 | 0.25 (0.13, 0.46) | 9 | 0.21 (0.13, 0.35) | 12 | 0.35 (0.18, 0.69) | 33 | 0.23 (0.12, 0.42) | |

CI=confidence interval, LBSS=London bicycle sharing system, OR=odds ratio. Adjusted odds ratios adjust for all variables in column.

Although overall LBSS bicycles made up 16% of the bicycles observed, this rose to 60% at one of the two apparently ‘recreational’ sites. This site, in London’s large Hyde Park on a Sunday afternoon, was also distinctive in that women were riding 45% of the 174 LBSS bicycles observed. By contrast women made up only 29% of the personal-bicycle cyclists observed in this park; 27% of LBSS cyclists observed outside this park; and 22% of the personal-bicycle cyclists observed outside this park. In total, 32% of the LBSS bicycles observed were ridden by women, compared to 23% of the personal bicycles.

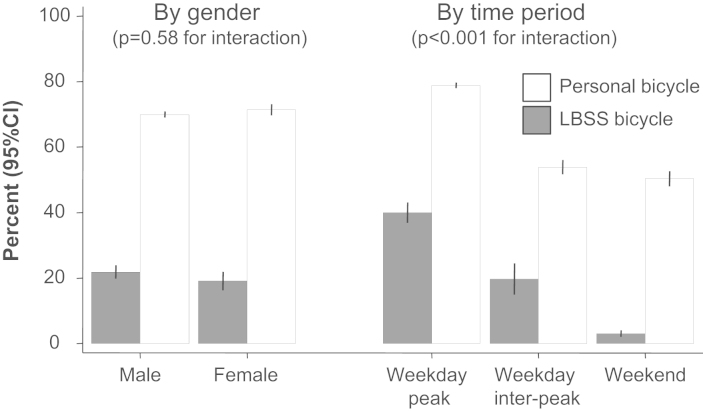

There was no evidence of gender differences in the associations between LBSS cycling and wearing cycling clothing (p>0.25 for gender interaction for all four outcomes shown in Table 1, see Fig. 1 for illustration with respect to ‘any’ cycling clothing). Similarly, LBSS cyclists on weekdays showed the same pattern as personal-bicycle cyclists in being more likely to wear cycling clothing during peak than inter-peak periods (all p>0.19 for interaction, see Fig. 1). At weekends, however, LBSS cyclists were particularly unlikely to wear helmets (p<0.001 for interaction) and perhaps high-visibility clothes (p=0.06, see also Fig. 1). Again, this pattern was similar after excluding the two apparently recreational sites.

Fig. 1.

Proportion of cyclists wearing any of the three types of cycling clothing recorded, stratified by gender, time period and bicycle type (N=3594 bicycles). CI=confidence interval, LBSS=London bicycle sharing system. P-values are for interaction between bicycle status (LBSS/personal) and either gender (left-hand side) or time period (right-hand side).

4. Discussion

In this observational study of 3500 adult London cyclists, London Bicycle Sharing System (LBSS) bicycles were much less likely to be ridden by someone wearing distinctive cycling clothing. This applied strongly to the two types of ‘safety’ clothing we recorded (helmets and high-visibility clothes) and even more strongly to cycling ‘sports clothes’. This inclusion of three types of cycling clothing is a strength of this study relative to one previous American study (Fischer et al., 2012), as is its random sampling of sites. One limitation is the fact that (like the previous study) we sampled across only one short period of the year. In addition, although our inter-rater reliabilities were fairly high (0.88–1), we will inevitably have made mistakes in recording some cyclists’ characteristics. This applies particularly to the category of ‘sports’ clothes, which sometimes required subjective judgements as to whether a particular item of clothing appeared to be designed for ‘sport’ or for ‘fashion’.

The Mayor of London recently announced his ambition to “de-Lycrafy” cycling (The Independent, 2013) and encourage “more of the kind of cyclists you see in Holland, going at a leisurely pace on often clunky steeds” (Greater London Authority, 2013, p. 5). The particularly low prevalence of sports clothes among LBSS cyclists suggests that this scheme may be contributing to realising the Mayor’s aim. As for the lower helmet use among BSS users, this has been raised as a safety concern in London (City of Westminster, 2010, The Guardian, 2010) and in other settings (Fischer et al., 2012, Shaheen et al., 2012). It is important to stress, however, that the trend thus far has been for LBSS cyclists to suffer lower injury rates than cyclists in central London in general (Woodcock et al., 2014). It is also worth noting that the 16% of LBSS cyclists wearing helmets is still much higher than the 2% figure reported for cycling for transport in a Dutch sample (Villamor et al., 2008).

Yet although LBSS users may not wear everyday clothing as often as Dutch cyclists, they still seem to do so far more often than London’s personal-bicycle cyclists (79% vs. 30% in this study). We believe that this stark difference may serve to encourage cycling in London by normalising somewhat the image of cycling. Qualitative research indicates that seeing other people cycling can be crucial in encouraging individuals to try out cycling themselves (Fishman et al., 2012), and that this applies particularly to seeing ‘people like yourself’ (Green et al., 2012). As one recent British study concludes, “everyday cyclists and potential everyday cyclists are unlikely to see the accoutrements of sports cycling (helmets, Lycra, bright clothing) as representing an image that they want to portray on their way to the shops” (Aldred, 2012b, p. 269). This has also been recognised by cycling activists, who have therefore sought to downplay images of ‘the helmet and Lycra cyclist’ and have instead framed recent campaigns as being about ‘Londoners on bikes’ (Aldred, 2013). As such, LBSS may not only encourage cycling directly, by providing bicycles people can rent, but also indirectly, by increasing the number and diversity of cycling ‘role models’ visible on London’s streets.

A second pathway whereby LBSS may indirectly encourage personal-bicycle cycling is hinted at by the large number of LBSS bicycles observed during the one Sunday afternoon observation site in a large park. This observation is intriguing given some evidence that, for novice cyclists in urban areas, acquiring skills as a leisure cyclist is an important precondition for taking up cycling for transport (Nettleton and Green, in press). Both in London and elsewhere (2013), longitudinal research would be very valuable to examine how far BSS use does in fact encourage subsequent use of personal bicycles. It is also notable that almost half the LBSS cyclists observed in this park setting were women, as opposed to an average of 22–27% for both LBSS and personal-bicycle cycling elsewhere. Operational data suggest that although ‘casual’ users only make 31% of LBSS trips in total, they make 75% of weekend trips in London’s parks (Woodcock et al., 2014). Our observations therefore support previous survey-based evidence (Woodcock et al., 2014) that extending LBSS access to ‘casual’ users has increased use by females relative to the very low initial proportions (Ogilvie and Goodman, 2012).

Fishman et al. (2013) have argued that, as a high-profile pro-cycling investment made (or at least facilitated) by the state, BSS have the potential to increase the public legitimacy of bicycle riding. We suggest that a corollary may also be true, namely that by normalising cycling as a valuable part of public transport (see also Shaheen et al., 2012), BSS may increase the public mandate for still more state investment in cycling. Although cycling has historically been marginalised within transport policy (Aldred, 2012a), ‘cycling as public transport’ has certainly become visible in London, with the distinctive LBSS bicycles contributing 16% of all bicycles observed in this study. The depiction of cycling facilities as one aspect of public transport provision is also evident in some more recent policy initiatives, such as the decision to create a new high-quality network of cycle routes following, and named after, the lines of the London underground (Greater London Authority, 2013). It is therefore possible that LBSS may not only encourage cycling among a larger and broader range of London’s potential cyclists, but may also help to embed cycling as a core aspect of public transport provision.

Acknowledgements

JW’s contribution to work was supported by the Centre for Diet and Activity Research (CEDAR), a UKCRC Public Health Research Centre of Excellence. Funding from the British Heart Foundation, Economic and Social Research Council, Medical Research Council, National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), and the Wellcome Trust, under the auspices of the UK Clinical Research Collaboration is gratefully acknowledged. AG contributed to this paper while funded by an NIHR post-doctoral fellowship, partly hosted by CEDAR. The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NIHR, Department for Health or other study funders. Many thanks to Shenaz Allyjaun and Fasiha Raza for their contributions to data collection.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.jth.2013.07.001.

Contributor Information

Anna Goodman, Email: anna.goodman@lshtm.ac.uk.

Judith Green, Email: judith.green@lshtm.ac.uk.

James Woodcock, Email: jw745@medschl.cam.ac.uk.

Appendix A. Supporting information

Supporting information

References

- Aldred R. Governing transport from welfare state to hollow state: the case of cycling in the UK. Transport Policy. 2012;23:95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Aldred R. Incompetent or too competent? Negotiating everyday cycling identities in a motor dominated society. Mobilities. 2012;8:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Aldred R. Who are Londoners on Bikes and what do they want? Negotiating identity and issue definition in a ‘pop-up’ cycle campaign. Journal of Transport Geography. 2013;30:194–201. [Google Scholar]

- City of Westminster, 2010. Delegated Authority Objections Report (7c): Traffic orders – London Cycle Hire Scheme: Appendix H, Available from: 〈http://westminstertransportationservices.co.uk/projects/pdfs/7c.pdf〉 (accessed 20.04.13).

- de Hartog J., Boogaard H., Nijland H., Hoek G. Do the health benefits of cycling outweigh the risks? Environmental Health Perspectives. 2010;118:1109–1116. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department for Transport . The Stationery Office; London: 2011. Creating growth, cutting carbon (Cm 7996) [Google Scholar]

- Fischer C., Sanchez C., Pittman M., Milzman D., Volz K., Huang H., Gautam S., Sanchez L. Prevalence of bicycle helmet use by users of public bikeshare programs. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2012;6:228–231. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman E., Washington S., Haworth N. Barriers and facilitators to public bicycle scheme use: a qualitative approach. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour. 2012;15:686–698. [Google Scholar]

- Fishman E., Washington S., Haworth N. Bike share: a synthesis of the literature. Transport Reviews. 2013;33:148–165. [Google Scholar]

- Greater London Authority . Greater London Authority; London: 2013. The Mayor’s vision for cycling in London: An Olympic Legacy for all Londoners. [Google Scholar]

- Green J., Steinbach R., Datta J. The travelling citizen: emergent discourses of moral mobility in a study of cycling in London. Sociology. 2012;46:272–289. [Google Scholar]

- Horton D. In: Fear of cycling. Cycling and Society. Horton D., Rosen P., Cox P., editors. Ashgate; Aldershot: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Maizlish N., Woodcock J., Co S., Ostro B., Fanai A. Health co-benefits and transportation-related reductions in greenhouse gas emissions in the San Francisco Bay area. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103:703–709. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Transport . Ministry of Transport, Public Works and Water Management, Directorate-General for Passenger Transport and Fietsberaad, Expertise Centre for Cycling Policy; Den Haag and Utrecht: 2009. Cycling in the Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Nettleton S., Green J. Thinking about changing mobility practices: how a social practice approach can help. Sociology of Health and Illness. 2013 doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.12101. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogilvie F., Goodman A. Inequalities in usage of a public bicycle sharing scheme: socio-demographic predictors of uptake and usage of the London (UK) cycle hire scheme. Preventive Medicine. 2012;55:40–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas-Rueda D., de Nazelle A., Tainio M., Nieuwenhuijsen M. The health risks and benefits of cycling in urban environments compared with car use: health impact assessment study. British Medical Journal. 2011;343:4521. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaheen S., Martin E., Cohen A.P., Finson R. Mineta Transportation Institute; San Jose, CA: 2012. Public Bikesharing in North America: Early Operator and User Understanding. [Google Scholar]

- Steinbach R., Green J., Datta J., Edwards P. Cycling and the city: a case study of how gendered, ethnic and class identities can shape healthy transport choices. Social Science & Medicine. 2011;72:1123–1130. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Guardian, 2010. London’s bike hire scheme is laudable – but where are the helmets? (05/08/2010). Available from: 〈http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2010/aug/05/cycling-helmets-safety〉 (accessed 29.04.13).

- The Independent, 2013. Boris Johnson wants to ‘de-Lycrafy cycling’ with £913 million plan for London (07/02/2013). Available from: 〈www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/boris-johnson-wants-to-delycrafy-cycling-with-913-million-plan-for-london-8523926.html〉 (accessed 29.04.13).

- Thornton A., Bunt K., Dalziel D., Simon A. Department for Transport; London: 2010. Climate Change and Transport Choices: Segmentation Study – Interim Report by TNS-BMRB. [Google Scholar]

- Transport for London . Transport for London; London: 2010. Analysis of Cycling Potential. [Google Scholar]

- Villamor E., Hammer S., Martinez-Olaizola A. Barriers to bicycle helmet use among Dutch paediatricians. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2008;34:743–747. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2008.00882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock, J., Tainio, M., Cheshire, J., O’Brien, O., Goodman, A., 2014. Modelled health impacts of the London bicycle sharing system. British Medical Journal 348, g425. 10.1136/bmj.g425 (http://www.bmj.com/content/348/bmj.g425). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting information