Abstract Abstract

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a chronic, symptomatic, life-threatening illness; however, it is complex, with variable expression regarding impact on quality of life (QOL). This study investigated attitudes and comfort of physicians regarding palliative care (PC) for patients with PAH and explored potential barriers to PC in PAH. An internet-based, mixed-methods survey was distributed to Pulmonary Hypertension Clinicians and Researchers, a professional organization within the Pulmonary Hypertension Association. Only responses from physicians involved in clinical care of patients with PAH were analyzed. Of 355 clinicians/researchers, 79 (22%) returned surveys, including 76 (21%) providers involved in clinical care. Responding physicians were mainly pulmonologists (67%), practiced in university/academic medical centers (89%), had been in practice a mean of 12 ± 7 years, cared for a median of 100 PAH patients per year, and reported a high level of confidence in managing PAH (87%), advanced PAH-specific pharmacologic interventions (95%), and end-of-life care (88%). Smaller proportions were comfortable managing pain (62%) and QOL issues (78%). Most physicians (91%) reported utilizing PC consultation at least once in the prior year, primarily in the setting of end-of-life/active dying (59%), hospice referral (46%), or symptomatic dyspnea/impaired QOL (40%). The most frequent reasons for not referring patients to PC included nonapproval by the patient/family (51%) and concern that PC is “giving up hope” (43%). PAH may result in symptoms that impair QOL despite optimal PAH therapy; however, PC awareness and utilization for PAH providers is low. Opportunities may exist to integrate PC into care for PAH patients.

Keywords: symptom control, palliative care, quality of life, pulmonary arterial hypertension

Introduction

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a serious, chronic medical illness caused by remodeling of the pulmonary vasculature and resulting in right heart failure, and it leads to an array of clinical manifestations and impaired quality of life (QOL). Median survival without treatment is 2.8 years1 but is significantly better in the current treatment era.2-6 Multiple studies and clinical trials have shown that novel pharmacologic agents can improve survival in patients with PAH;2,5 however, symptom burden and QOL can remain challenging.7-10 While palliative care (PC) has been gaining acceptance as a part of care for patients with advanced heart failure,11-15 and a recently published study looked at attitudes and barriers to PC in heart failure,15 there is a paucity of literature investigating how clinicians who manage PAH have adopted this approach. In this study, we evaluate the perception of clinicians regarding symptom burden that patients may experience. We attempt to quantify physician attitudes regarding PC for patients with PAH, in an effort to determine whether there is an opportunity to incorporate such principles in PAH patient management. We hypothesized that physicians who care for patients with PAH have a reluctance to utilize PC consultation for end-of-life issues and symptom control.

Methods

Study approval was obtained from the Pulmonary Hypertension Clinicians and Researchers (PHCR), an organization within the Pulmonary Hypertension Association, and the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board (Rochester, MN) before survey dissemination. Concurrent separate surveys were distributed to Pulmonary Hypertension Association listserv subscribers, including patients and caregivers; this analysis focuses on the survey of physicians who provide direct care for patients with PAH.

The survey (see appendix (174.6KB, pdf) ) included a physician self-assessment of comfort with primary management and therapeutics for PAH as well as an assessment of referrals to and utilization of PC resources. Physician self-reported comfort with managing acute and chronic pain and other QOL markers was evaluated, and potential barriers to PC consultation were explored. Survey questions were directed at evaluating comfort level with assessment and management of disease-related symptoms, QOL issues, pain in patients with PAH, advanced PAH pharmacologic interventions, patient/family discussion on death and dying, and supportive-care measures. Respondent comfort-level responses were measured on a 5-point Likert scale (“very comfortable,” “somewhat comfortable,” “neither comfortable nor uncomfortable,” “somewhat uncomfortable,” and “very uncomfortable”). For analysis, “very comfortable” and “somewhat comfortable” were grouped together.

A case vignette (Box 1) describing a seriously ill patient with advanced, end-stage PAH was used to assess clinician management styles and willingness to consider therapeutic options with varying degrees of potential benefit, harm, and invasiveness. The vignette encouraged physicians to choose all options they would consider for treating this patient (intravenous diuretic, oxygen, clinical trial, atrial septostomy, ultrafiltration, PC consultation, opioid therapy, hospice, and/or pulmonary rehabilitation). Surveys were electronically administered anonymously by a third party (Mayo Clinic Survey Research Center) to maintain security, and investigators reviewed only deidentified data.

Box 1.

A 55-year-old female with PAH presents as your patient. She was diagnosed with primary PAH 4-1/2 years ago when she presented with dyspnea on exertion. She was initially treated with amlodipine. After an initial response waned, she was then treated with sildenafil and bosentan. She continued to have worsening right ventricular end diastolic pressure (RVEDP) on imaging and worsening right heart failure and underwent right heart catheterization. Her RV end diastolic volumes were markedly elevated and her PA pressure was 91/33 (systemic blood pressure 89/49). The patient then had a trial of epoprostenol but did not tolerate this medication due to nausea, hypoxia, and systemic hypotension. Based on her current clinical situation, you estimate her survival between 6 and 12 months. She is profoundly dyspneic, and has gained 15 kg of fluid weight.

Results were analyzed descriptively, with categorical data reported as percentages and continuous variables reported as means ± standard deviations or medians with interquartile ranges, as appropriate. Data were collected and analyzed with SAS (Cary, NC). Free-text responses regarding barriers to PC were independently reviewed by 2 investigators (KMS and TDS), with qualitative themes identified and consensus obtained.

Results

Physician self-reported characteristics and attitudes

Of 355 physicians and researchers with active e-mail addresses registered with the PHCR, 79 returned completed surveys (22% overall response). Of these, 76 (96%; 21% of the total) were eligible physicians who were involved in the clinical care of patients with PAH. Baseline survey characteristics are shown in Table 1. Most physicians were pulmonologists (67%). Most practiced in a university or academic setting (89%), were midcareer, with a mean age of 48 ± 9 years, and had been in clinical practice for a mean of 12 ± 7 years. Physicians reported caring for a median of 100 patients (interquartile range [IQR]: 35–150) with PAH annually, with common use of oral PAH medications (median 73; IQR: 30–125). A median of 22 (IQR: 5–50) of their patients per year were treated with parenteral prostacyclin analogs.

Table 1.

Baseline respondent characteristics

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Mean age ± SD, years (n = 75) | 48 ± 9 |

| Mean time in practice ± SD, years (n = 74) | 12 ± 7 |

| Clinical characteristics, n (%) | |

| Primary specialty | |

| Pulmonologist | 50 (67) |

| Cardiologist | 20 (27) |

| Other | 5 (7) |

| Practice type (n = 75) | |

| University or academic medical center | 67 (89) |

| Private physician | 7 (9) |

| Government facility | 0 (0) |

| Other | 1 (1) |

| Missing | 1 (1) |

| No. of PAH patients seen per year in clinical practice, median (IQR) | 100 (35, 150) |

| No. of PAH patients cared for on oral PH medications, median (IQR) | 73 (30, 125) |

| No. of PAH patients cared for on parenteral prostanoids, median (IQR) | 22 (5, 50) |

| No. of physicians who referred a patient with PAH for atrial septostomy (%) | 31 (41) |

| No. of physicians who referred a patient with PAH for heart and/or lung transplant (%) | 67 (88) |

| No. of physicians who referred a patient with PAH for palliative care consultation (%) | 55 (72) |

n = 76 respondents unless otherwise specified. PAH: pulmonary arterial hypertension; IQR: interquartile range (i.e., 25th–75th percentiles); PH: pulmonary hypertension.

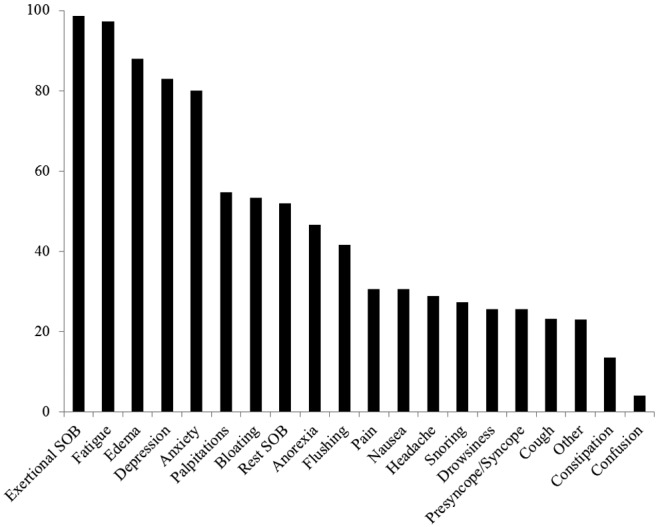

Physicians reported their perception that the most commonly encountered symptoms affecting patients whom they treated were exertional dyspnea (99%), fatigue (97%), edema (88%), depression (83%), and anxiety (80%; Figure 1). Regarding self-assessment of practice patterns, physicians reported the highest comfort levels in assessment of PAH-specific, disease-related symptoms (88%) and symptom management (87%). The majority of physicians (95%) reported feeling comfortable or very comfortable with advanced PAH-specific pharmacologic interventions (i.e., prostanoids, endothelin receptor antagonists), while a majority (88%) also reported a high degree of confidence regarding end-of-life care plans and discussion with patients and their families. Physicians reported less comfort in assessing and managing supportive-care measures, including QOL-related issues, as only 43% of physicians were very comfortable in assessing QOL and 33% were very comfortable managing QOL issues. Similarly, only 36% of physicians were very comfortable regarding pain assessment, and 14% were very comfortable with pain management using opioids, antidepressants, or other neuromodulatory agents (i.e., gabapentin) for neuropathic pain.

Figure 1.

Symptoms encountered most often in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Y-axis shows percent of respondents. SOB: shortness of breath.

In regard to PC utilization, a majority (91%) of PAH physicians reported obtaining a PC consultation at least once in the 12 months prior to the survey. The most common reasons for obtaining a PC consultation was in the setting of end of life or active dying (59%) or for hospice referral (46%; Table 2). Forty percent of PC consultations were obtained for either assistance with dyspnea management or assistance with impaired patient QOL. Table 3 highlights physician-perceived barriers to PC consultation. When asked about potential barriers to referral for PC, the most frequently cited reasons included nonapproval by the patient/family (51%) and a view that PC is “giving up hope” (43%), while 36% of respondents felt comfortable addressing QOL, symptom management, and end-of-life issues without PC consultation. In addition, 28% of physicians believed that PAH patients were not eligible to have PC if prostanoids were continued, and 20% thought that PC involvement resulted in difficulty treating the PAH as aggressively as necessary.

Table 2.

Common reasons reported by physicians for palliative medicine referral in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension

| Reasons | n (%) |

|---|---|

| End of life/active dying | 45 (59) |

| Hospice referral | 35 (46) |

| Dyspnea management | 30 (39) |

| Impaired quality of life | 30 (39) |

| Goals-of-care discussion | 24 (32) |

| Pain management | 19 (25) |

| Other symptoms | 11 (14) |

Percentages are based on n = 76 respondents.

Table 3.

Physician-perceived barriers to palliative care

| Barrier statement | Respondents who agree, n (%) |

|---|---|

| PAH patient or family was not agreeable to consultation | 39 (51) |

| There is concern that palliative medicine consultation may be viewed by patients as “giving up hope” | 33 (43) |

| I am comfortable dealing with issues of quality of life and end-of-life care and do not feel palliative care consultation was necessary | 27 (36) |

| PAH patients are not eligible to have palliative care if they continue to receive active therapies (i.e., prostanoids) | 21 (28) |

| It is hard to treat PAH as aggressively as is needed and have palliative care at the same time | 15 (20) |

| Given that many PAH patients are young, it is hard to consider them for palliative medicine consultation | 14 (18) |

| The name “palliative” has a negative connotation | 13 (17) |

| PAH patients have a chronic disease, may live for years, and are not appropriate for palliative medicine as they are not “end-of-life” | 8 (11) |

| Palliative medicine and hospice are the same thing, and the patient wasn’t ready for hospice | 5 (6) |

Percentages are based on n = 76 respondents. PAH: pulmonary arterial hypertension.

Vignette responses

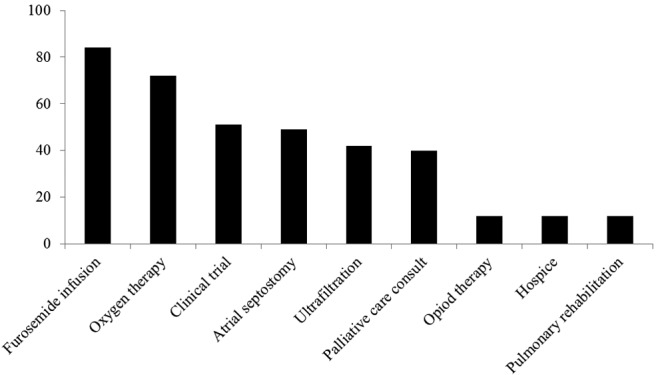

In response to a clinical vignette asking for appropriate treatment options for a patient with advanced PAH (World Health Organization class IV symptoms) and an expected survival of less than 1 year, the majority of physicians considered use of diuretics and oxygen. Many respondents considered aggressive therapies with variable efficacy, including a clinical trial (51%) or atrial septostomy (49%). In contrast, only 40% of respondents considered PC consultation, and only 12% of clinicians considered referral to hospice as an appropriate option at that time (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Interventions considered in response to the clinical vignette (Box 1). Y-axis shows percent of respondents.

Discussion

The physician-respondents in this study represented predominantly pulmonology or cardiology physicians with academic or university ties who also possessed a high level of expertise in treating patients with advanced disease, as evident by the number of patients on intravenous prostanoid therapy. Despite a high level of self-reported comfort in treating patients with PAH and recognition of the symptom burden, only 40% of responding physicians considered PC an appropriate adjunct to traditional PAH therapies, despite reporting less overall comfort in treating QOL symptom burden and end-of-life scenarios. More frequently, physicians considered aggressive, invasive, non-evidence-based measures such as atrial septostomy or clinical trials for patients who may be approaching the end of life (Figure 2). Although atrial septostomy may be appropriate to consider in select patients refractory to maximal medical therapy, the procedure lacks robust study in randomized clinical trials, with data limited to single-center experiences.16-19 Perhaps more important is the concept that PC can coexist with aggressive PAH treatment, including interventional and surgical procedures, and may be adjunctive to symptom control, particularly when advanced therapies are involved.15,20,21 In our study, we aimed to identify physician-perceived potential barriers to PC involvement in the care of patients with PAH. More than half of all responding physicians (51%) cited nonapproval of the patient or family regarding PC involvement, while 43% of physicians felt that PC consultation may be perceived as “giving up hope.” A major barrier to PC consultation may also include misunderstanding of the scope and goals of PC, as 17% of respondents agreed that the term “palliative” has a negative connotation.

Patients with PAH frequently have profound and multifactorial symptom burden that negatively affects QOL and may persist despite optimal PAH therapy.7,22-26 In a cross-sectional, internet-based survey of 276 patients with PAH, respondents reported significant impairment with regard to fatigue (57%), physical well-being (56%), limitation of social activity (49%), emotional well-being (49%), and pain (38%).10 Despite impaired QOL, utilization of PC was reported to be low in patients with PAH, and misperceptions regarding PC exist. In the aforementioned study, 40% of patients reported impairment of QOL due to symptoms, yet only 1.4% reported involvement of a PC specialist in their PAH-directed care.10 The mismatch between symptom perception and the role of PC can be considerable, as 63% of those patients did not believe that they were “sick enough” to warrant PC involvement.10

Concerns that PC equates to giving up or lack of aggressiveness have been expressed previously by patients10 and by some physicians in this survey. The thought may be coupled with concerns that survival will be limited with pursuit of PC. However, it has been demonstrated in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer that early incorporation of PC along with conventional, disease-targeted therapy improved QOL, resulted in less depression, and improved median survival (11.6 months vs. 8.9 months), compared to “standard care” in similar patients.27

System barriers may exist within institutions (e.g., lack of access or availability of services) that prevent palliative medicine involvement. Inpatient use of PC for patients with PAH occurs infrequently, yet two-thirds of patients with PAH die in the hospital, despite patient preferences to die at home.28 Despite numerous interventions in patients with heart failure, readmissions continue to place a major burden on both the healthcare system and patients.29-32 PC consultation can help caregivers address patient expectations, update patients on prognosis, and discuss goals of care, especially when the disease trajectory changes or patient expectations are discordant with prognosis.20,21,33,34 These moments facilitate open communication, empower patient decision making, and develop rapport and can optimally occur in collaboration with the primary PAH-treating clinicians.

By seeking to improve QOL in patients with PAH and by improved public awareness, PC has the potential to become routine in concert with aggressive, life-prolonging, PAH-targeted therapies.20 The role of PC in the care of patients with cardiovascular illnesses has been emphasized in recent European and American guidelines, with recommended annual visits to discuss anticipated and unanticipated events, including end-of-life care.13,14 Clinical interventions focusing on routine evaluation of these issues and triggers to consider PC have been well received in patients with advanced heart failure and in patients who have undergone implantation of mechanical circulatory support.35 Finally, a recently published qualitative study demonstrated that patients with heart failure often do not get adequate PC for several of the reasons noted in this study, including limited provider knowledge and misperceptions regarding role of PC.15

Risk prediction in the setting of PAH, using validated tools that incorporate clinical and hemodynamic variables for prognostication, can be helpful with respect to survival,6,36 but such tools do not incorporate QOL measures or patient-reported outcomes. QOL questionnaires for patients with heart failure were traditionally designed for patients with left-sided heart failure37,38 and extrapolated for use in patients with PAH.23,24,39 Inherent challenges exist with the use of specific questionnaires in different populations of patients.22 These obstacles prompted the creation of a disease-specific QOL questionnaire directed at assessing domains that directly affect patients with PAH40 that has been validated in patients with group 1 pulmonary hypertension in the United States.41

As disease-specific questionnaires become integrated into practice, physicians may further appreciate the effect that PAH-related symptoms and medication side effects have, both positive and negative, on QOL. Addressing QOL entails a deeper understanding of patients and how their disease and treatments affect them on the physical, mental, and spiritual levels. Although survival has improved for patients with PAH, morbidity and mortality remain significantly increased compared to patients without PAH, and many patients with PAH face end of life prematurely. Previous work,10 along with this study, highlights common misperceptions that may serve as barriers to PC consultation in the setting of PAH. However, we believe that PC consultation can work in concert with PAH-targeted therapy when implemented in a patient-centered, team-based approach that helps patients to achieve their goals of care and that it may be one of many quality metrics for designation as a pulmonary hypertension center of excellence.

Conclusions. Experienced PAH physicians report feeling a higher comfort level when managing PAH-specific pharmacologic interventions or treatments than when focusing on other QOL issues. PC utilization is low in PAH, and misperceptions of PC appear to commonly permeate physician thought and practice. Efforts at integration of PC may be a means of improving QOL and may assist PAH providers in symptom management and complex communication issues.

Source of Support: Internal funding.

Conflict of Interest: RPF has received research grants, unrelated to this project, from United Therapeutics and has served on data safety monitoring boards for Actelion and United Therapeutics and advisory boards for Actelion, Pfizer, Gilead, and United Therapeutics. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The initial abstract and poster were presented at Pulmonary Hypertension Association’s 9th International Pulmonary Hypertension Conference and Scientific Sessions, Garden Grove, California, June 24–27, 2010, and as an oral presentation at International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation, Prague, Czech Republic, April 18, 2012.

Supplements

Provider survey (174.6KB, pdf)

References

- 1.D’Alonzo GE, Barst RJ, Ayres SM, Bergofsky EH, Brundage BH, Detre KM, Fishman AP, et al. Survival in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension: results from a national prospective registry. Ann Intern Med 1991;115(5):343–349. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Barst RJ, Rubin LJ, Long WA, McGoon MD, Rich S, Badesch DB, Groves BM, et al. A comparison of continuous intravenous epoprostenol (prostacyclin) with conventional therapy for primary pulmonary hypertension. N Engl J Med 1996;334(5):296–301. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Sitbon O, Humbert M, Nunes H, Parent F, Garcia G, Hervé P, Rainisio M, Simonneau G. Long-term intravenous epoprostenol infusion in primary pulmonary hypertension: prognostic factors and survival. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;40(4):780–788. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.McLaughlin VV, Shillington A, Rich S. Survival in primary pulmonary hypertension: the impact of epoprostenol therapy. Circulation 2002;106(12):1477–1482. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Humbert M, Sitbon O, Simonneau G. Treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med 2004;351(14):1425–1436. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Benza RL, Miller DP, Gomberg-Maitland M, Frantz RP, Foreman AJ, Coffey CS, Frost A, et al. Predicting survival in pulmonary arterial hypertension: insights from the Registry to Evaluate Early and Long-Term Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Disease Management (REVEAL). Circulation 2010;122(2):164–172. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Chen H, Taichman DB, Doyle RL. Health-related quality of life and patient-reported outcomes in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2008;5(5):623–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Matura LA, Carroll DL. Human responses to pulmonary arterial hypertension: review of the literature. J Cardiovasc Nurs 2010;25(5):420–427. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Matura LA, McDonough A, Carroll DL. Cluster analysis of symptoms in pulmonary arterial hypertension: a pilot study. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2012;11(1):51–61. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Swetz KM, Shanafelt TD, Drozdowicz LB, Sloan JA, Novotny PJ, Durst LA, Frantz RP, McGoon MD. Symptom burden, quality of life, and attitudes toward palliative care in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: results from a cross-sectional patient survey. J Heart Lung Transplant 2012;31(10):1102–1128. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Pantilat SZ, Steimle AE. Palliative care for patients with heart failure. JAMA 2004;291(20):2476–2482. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Goodlin SJ. Palliative care in congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;54(5):386–396. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Jaarsma T, Beattie JM, Ryder M, Rutten FH, McDonagh T, Mohacsi P, Murray SA, et al. Palliative care in heart failure: a position statement from the palliative care workshop of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail 2009;11(5):433–443. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Allen LA, Stevenson LW, Grady KL, Goldstein NE, Matlock DD, Arnold RM, Cook NR, et al. Decision making in advanced heart failure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2012;125(15):1928–1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Kavalieratos D, Mitchell EM, Carey TS, Dev S, Biddle AK, Reeve BB, Abernethy AP, Weinberger M. “Not the ‘grim reaper service’”: an assessment of provider knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions regarding palliative care referral barriers in heart failure. J Am Heart Assoc 2014;3(1):e000544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Sandoval J, Gaspar J, Pulido T, Bautista E, Martínez-Guerra ML, Zeballos M, Palomar A, Gómez A. Graded balloon dilation atrial septostomy in severe primary pulmonary hypertension: a therapeutic alternative for patients nonresponsive to vasodilator treatment. J Am Coll Cardiol 1998;32(2):297–304. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Sandoval J, Gaspar J, Pena H, Santos LE, Córdova J, del Valle K, Rodríguez A, Pulido T. Effect of atrial septostomy on the survival of patients with severe pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J 2011;38(6):1343–1348. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Corris PA. Atrial septostomy and transplantation for patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2009;30(4):493–501. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Reichenberger F, Pepke-Zaba J, McNeil K, Parameshwar J, Shapiro LM. Atrial septostomy in the treatment of severe pulmonary arterial hypertension. Thorax 2003;58(9):797–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Kimeu AK, Swetz KM. Moving beyond stigma—are concurrent palliative care and management of pulmonary arterial hypertension irreconcilable or future best practice? Int J Clin Pract 2012;66(suppl. 177):2–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Swetz KM, Kamal AH. Palliative care. Ann Intern Med 2012;156(3):ITC2-1–ITC2-16. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-156-3-201202070-01002. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Rubenfire M, Lippo G, Bodini BD, Blasi F, Allegra L, Bossone E. Evaluating health-related quality of life, work ability, and disability in pulmonary arterial hypertension: an unmet need. Chest 2009;136(2):597–603. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Taichman DB, Shin J, Hud L, Archer-Chicko C, Kaplan S, Sager JS, Gallop R, Christie J, Hansen-Flaschen J, Palevsky H. Health-related quality of life in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Respir Res 2005;6:92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Shafazand S, Goldstein MK, Doyle RL, Hlatky MA, Gould MK. Health-related quality of life in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Chest 2004;126(5):1452–1459. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Zlupko M, Harhay MO, Gallop R, Shin J, Archer-Chicko C, Patel R, Palevsky HI, Taichman DB. Evaluation of disease-specific health-related quality of life in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Respir Med 2008;102(10):1431–1438. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Péloquin J, Robichaud-Ekstrand S, Pepin J. Quality of life perception by women suffering from stage III or IV primary pulmonary hypertension and receiving prostacyclin treatment [in French with English abstract]. Can J Nurs Res 1998;30(1):113–136. [PubMed]

- 27.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, Dahlin CM, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363(8):733–742. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Grinnan DC, Swetz KM, Pinson J, Fairman P, Lyckholm LJ, Smith T. The end-of-life experience for a cohort of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Palliative Med 2012;15(10):1065–1070. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Bradley EH, Curry L, Horwitz LI, Sipsma H, Wang Y, Walsh MN, Goldmann D, White N, Piña IL, Krumholz HM. Hospital strategies associated with 30-day readmission rates for patients with heart failure. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2013;6(4):444–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Bonow RO, Ganiats TG, Beam CT, Blake K, Casey DE Jr., Goodlin SJ, Grady KL, et al. ACCF/AHA/AMA-PCPI 2011 performance measures for adults with heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures and the American Medical Association–Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement. Circulation 2012;125(19):2382–2401. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Krumholz HM, Amatruda J, Smith GL, Mattera JA, Roumanis SA, Radford MJ, Crombie P, Vaccarino V. Randomized trial of an education and support intervention to prevent readmission of patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;39(1):83–89. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Hernandez AF, Greiner MA, Fonarow GC, Hammill BG, Heidenreich PA, Yancy CW, Peterson ED, Curtis LH. Relationship between early physician follow-up and 30-day readmission among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for heart failure. JAMA 2010;303(17):1716–1722. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Swetz KM, Mansel JK. Ethical issues and palliative care in the cardiovascular intensive care unit. Cardiol Clin 2013;31(4):657–668. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Goldstein NE, May CW, Meier DE. Comprehensive care for mechanical circulatory support: a new frontier for synergy with palliative care. Circ Heart Fail 2011;4(4):519–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Swetz KM, Freeman MR, AbouEzzeddine OF, Carter KA, Boilson BA, Ottenberg AL, Park SJ, Mueller PS. Palliative medicine consultation for preparedness planning in patients receiving left ventricular assist devices as destination therapy. Mayo Clin Proc 2011;86(6):493–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Benza RL, Miller DP, Barst RJ, Badesch DB, Frost AE, McGoon MD. An evaluation of long-term survival from time of diagnosis in pulmonary arterial hypertension from the REVEAL registry. Chest 2012;142(2):448–456. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Green CP, Porter CB, Bresnahan DR, Spertus JA. Development and evaluation of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire: a new health status measure for heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;35(5):1245–1255. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Sauser K, Spertus JA, Pierchala L, Davis E, Pang PS. Quality of life assessment for acute heart failure patients from emergency department presentation through 30 days post-discharge: a pilot study with the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire. J Card Fail 2014;20(1):18–22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Cenedese E, Speich R, Dorschner L, Ulrich S, Maggiorini M, Jenni R, Fischler M. Measurement of quality of life in pulmonary hypertension and its significance. Eur Respir J 2006;28(4):808–815. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.McKenna SP, Doughty N, Meads DM, Doward LC, Pepke-Zaba J. The Cambridge Pulmonary Hypertension Outcome Review (CAMPHOR): a measure of health-related quality of life and quality of life for patients with pulmonary hypertension. Qual Life Res 2006;15(1):103–115. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Gomberg-Maitland M, Thenappan T, Rizvi K, Chandra S, Meads DM, McKenna SP. United States validation of the Cambridge Pulmonary Hypertension Outcome Review (CAMPHOR). J Heart Lung Transplant 2008;27(1):124–130. [DOI] [PubMed]