Abstract Abstract

The age at diagnosis of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) and the prevalence of cardiovascular (CV) risk factors are increasing. We sought to determine whether the response to drug therapy was influenced by CV risk factors in PAH patients. We studied consecutive incident PAH patients (n = 146) between January 1, 2008, and July 15, 2011. Patients were divided into two groups: the PAH–No CV group included patients with no CV risk factors (obesity, systemic hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, permanent atrial fibrillation, mitral and/or aortic valve disease, and coronary artery disease), and the PAH-CV group included patients with at least one. The response to PAH treatment was analyzed in all the patients who received PAH drug therapy. The PAH–No CV group included 43 patients, and the PAH-CV group included 69 patients. Patients in the PAH–No CV group were younger than those in the PAH-CV group (P < 0.0001). In the PAH–No CV group, 16 patients (37%) improved on treatment and 27 (63%) did not improve, compared with 11 (16%) and 58 (84%) in the PAH-CV group, respectively (P = 0.027 after adjustment for age). There was no difference in survival at 30 months (P = 0.218). In conclusion, in addition to older age, CV risk factors may predict a reduced response to PAH drug therapy in patients with PAH.

Keywords: pulmonary arterial hypertension, cardiovascular risk factors, pulmonary arterial hypertension–targeted treatment

Introduction

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a rare progressive disease that leads to right heart failure and death.1 PAH drug therapies have significantly improved symptoms, hemodynamics, and exercise capacity in patients with PAH.2-4 The age at diagnosis of PAH has been gradually shifting to older age over the last decade,5-8 while the United Kingdom and Ireland registry has identified a less good outcome in older compared with younger patients,7 and COMPERA (Comparative, Prospective Registry of Newly Initiated Therapies for Pulmonary Hypertension) has shown that older patients respond less well to PAH drugs.8

As patients age, there is an increase in the prevalence of cardiovascular (CV) risk factors predisposing to left heart disease.6-8 Postcapillary pulmonary hypertension (PH) is driven by left heart disease and according to current guidelines should not be treated by PAH drugs.9,10 Given that most of the randomized controlled trials of PAH drug therapies have included younger patients,2-4 it is an open question whether these therapies are equally beneficial in patients with coexisting CV risk factors that may affect the left heart.

In this study, we sought to determine whether the response to PAH drug therapy in patients with PAH was influenced by conventional CV risk factors. We compared PAH patients to those without CV risk factors as well as to patients with PH due to left heart disease to examine whether they share some of the characteristics of left heart disease.

Methods

Study design: definitions

This study was conducted in the National Pulmonary Hypertension Service at Hammersmith Hospital, London, which is one of seven nationally designated referral centers in the United Kingdom. We collected and examined data on consecutive, incident PH patients seen and investigated between January 1, 2008, and July 15, 2011. Incident PH patients were defined as patients with PH presenting for the first time to a specialist PH center who had never received PAH drug therapy. All patients underwent investigation of PH according to current guidelines.9,10 PH was defined by mean pulmonary arterial pressure (mPAP) of ≥25 mmHg on cardiac catheterization.9,10

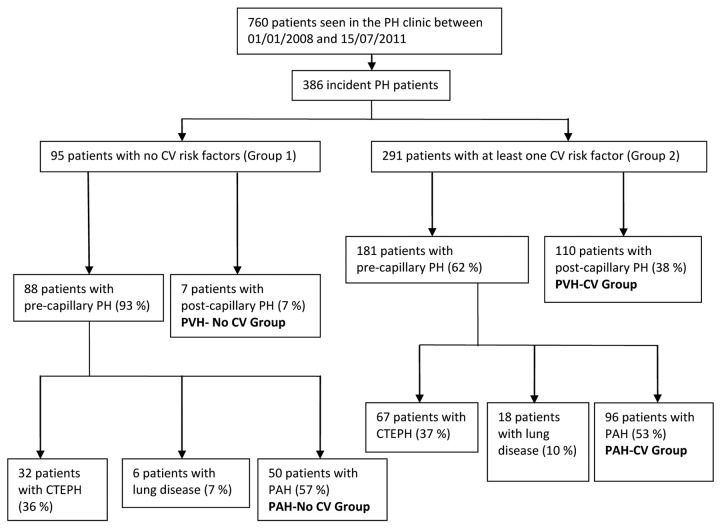

We divided the patients into two groups according to the presence of CV risk factors: group 1 had no risk factors, and group 2 had at least one risk factor (Fig. 1). These risk factors included obesity, systemic hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, permanent atrial fibrillation, aortic and/or mitral valve disease, and coronary artery disease.11-16

Figure 1.

Consort diagram of the study. PH: pulmonary hypertension; CV: cardiovascular; PVH: pulmonary venous hypertension; CTEPH: chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension; PAH: pulmonary arterial hypertension.

Systemic hypertension was defined by systolic blood pressure of >140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure of >90 mmHg recorded in more than two measurements, by physician-documented history of hypertension, or by chronic use of antihypertensive medications. Diabetes mellitus was defined by the presence of a physician-documented history or prescription of oral hypoglycemic agents or insulin for the treatment of hyperglycemia. Permanent atrial fibrillation was defined as atrial fibrillation accepted by patient and physician.17 Coronary artery disease was defined by the presence of physician-documented history, known coronary stenosis of >50%, prior history of myocardial infarction, previous percutaneous coronary intervention, coronary artery bypass grafting, or abnormal stress test consistent with myocardial ischemia. Obesity was defined by a body mass index of ≥30 (calculated as the weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters). Valve disease was defined by at least moderate mitral stenosis, mitral regurgitation, aortic stenosis, and/or aortic regurgitation demonstrated by echocardiography according to current guidelines.18

We further divided the patients of groups 1 and 2 into two additional groups according to the presence of pre- or postcapillary PH (Fig. 1). Precapillary PH was defined by mPAP of ≥25 mmHg, pulmonary arterial wedge pressure (PAWP) of ≤15 mmHg, and/or left ventricular end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP) of ≤16 mmHg and normal or reduced cardiac output, and postcapillary PH was defined as mPAP of ≥25 mmHg, PAWP of >15 mmHg, and/or LVEDP of >16 mmHg and normal or reduced cardiac output.10,19

As the number of patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction who were referred to our center was small, we excluded them on the basis of left ventricular ejection fraction of ≤50% measured on the echocardiogram by Simpson’s method.19 We also excluded patients with chronic thromboembolic PH and PH due to lung disease and/or hypoxia.

Variables analyzed

We analyzed parameters identified and obtained during the first visit to the clinic with the exception of hemodynamic data. As the time between the first visit to the clinic and catheterization did not exceed 3 weeks, we assumed that these variables had not significantly changed in this time.

We conducted a 6-minute walk test (6MWT) according to American Thoracic Society guidelines.20 We examined the electrocardiogram (ECG) and determined heart rhythm, the presence of complete right bundle branch block (defined by rSR′ or qRs morphology in V1 lead and QRS duration of >120 ms), a dominant R wave in V1 lead (R > S), right ventricular strain (ST segment deviation and T-wave inversion in V1–V3),21 and right axis deviation (QRS axis of >100°).

All echocardiograms recorded at the first visit were reviewed. The measurements were made according to American Society of Echocardiography guidelines.22 We also calculated the ratio of end-diastolic basal right ventricular diameter (at the tips of the tricuspid valve) to end-diastolic basal left ventricular diameter (at the tips of the mitral valve) in the 4-chamber view (RV/LV ratio) as a marker of the ventricular predominance in terms of dimensions.23 The echocardiographic variables that had not been measured in the first instance were measured retrospectively off-line, on stored images. All of the echocardiographic variables were measured independently by two echocardiographers who were masked to the hemodynamic data.

Finally, we analyzed hemodynamics. Cardiac output was measured using the Fick principle with estimated oxygen consumption, cardiac index was calculated as cardiac output divided by body surface area, and pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) was calculated as the difference between mPAP and PAWP divided by pulmonary flow. Transpulmonary gradient was calculated as mPAP minus PAWP, and diastolic pulmonary pressure difference was calculated as diastolic pulmonary arterial pressure minus PAWP.

Response to treatment

The majority of patients with PAH received PAH drug therapies. The reasons why some of the PAH patients were not started on treatment included drug therapy not being funded at that time in England for New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class II or patients having PAH related to conditions in which the underlying cause needed to be treated prior to considering PAH drugs (e.g., closure of atrial septal defects, immunosuppression for systemic lupus erythematosus).

We identified the response to PAH drugs at the last available patient visit to the PH clinic compared with the baseline before treatment was commenced. Improvement on treatment was defined as a combined improvement in NYHA functional class plus an increase in 6MWT distance (6MWTD) of ≥15% compared with baseline. Patients who failed to meet these criteria were classified as having no improvement on treatment.

Worsening on treatment was defined as a combined deterioration of NYHA functional class after treatment or failure to improve from NYHA functional class IV plus a decrease in 6MWTD of ≥15% or death. The patients who did not meet the criteria of improvement or worsening were considered to be stable.

Combination therapy included a phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor plus an endothelin receptor antagonist or a phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor and/or an endothelin receptor antagonist plus prostacyclin.

Statistical analysis

PH patients were assigned to one of four groups: PAH with no CV risk factors (PAH–No CV group), PAH with CV risk factors (PAH-CV group), PH related to left heart disease with CV risk factors (PVH-CV group), and PH with postcapillary hemodynamics and no CV risk factors (PVH–No CV group; Fig. 1).

We compared the groups as follows: PAH–No CV to PAH-CV and PAH-CV to PVH-CV. The PVH–No CV group included only a small number of patients (7 patients) with variable etiology of left heart disease and was not analyzed further.

Categorical data are expressed as number of patients (%), while continuous data are presented as median (inter quartile range), as some were not normally distributed. Between-group differences were assessed by the χ2 test for categorical variables and by the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables.

As we compared a large number of variables between the groups, we applied a post hoc Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons, which raised the threshold of statistical significance to 0.001. We report a trend toward a difference when a P value was <0.05. We did not apply a Bonferroni correction for the comparison of response to treatment.

As patients in the PAH-CV group were significantly older than those in the PAH–No CV group, we performed age adjustment using logistic regression to determine differences in clinical characteristics, response to PAH treatment, and survival between these groups.

Survival was estimated from the time of PH diagnosis to all-cause mortality or end of study. Univariate Cox regression was used to test for differences between survival probabilities of different PH groups. For the survival analysis, all patients were censored at a fixed date (March 13, 2013) or on the date of death if earlier. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (ver. 10).

Results

PAH–No CV group versus PAH-CV group

Differences between the PAH–No CV and PAH-CV groups are listed in Tables 1 and 2. Patients in the PAH-CV group were significantly older than those without CV risk factors. There was no difference in the types of PAH, symptoms, clinical signs, or 6MWTD across the groups (Table 1). The ECG findings were not different after adjustment for age and Bonferroni correction (Table 2). There was no significant difference in medications, brain natriuretic peptide levels, and echocardiographic variables. On echocardiogram there was a trend toward greater left ventricular posterior wall thickness and left atrial diameter in the PAH-CV group, while for hemodynamics there was a trend toward higher PAWP and LVEDP (Table 2).

Table 1.

Comparison of demographic and clinical data

| P value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | PAH–No CV (n = 50) | PAH-CV (n = 96) | PVH-CV (n = 110) | PAH–No CV vs. PAH-CV | PAH-CV vs. PVH-CV |

| Demographics | |||||

| Age, years | 46 (34–64) | 65 (59–73) | 70 (60–76) | <0.0001 | 0.045 |

| Female, no. (%) | 30 (60) | 57 (59.4) | 69 (62.7) | 0.942 | 0.622 |

| BMI | 25 (21.2–26.8) | 30.5 (24.6–35.5) | 29.7 (26–38) | <0.0001/<0.0001 | 0.215 |

| BSA, m2 | 1.73 (1.6–1.9) | 1.83 (1.7–2.05) | 1.91 (1.78–2.12) | <0.0001/<0.0001 | 0.043 |

| Cardiovascular comorbidities, no. (%) | |||||

| Obesity | … | 49 (52.7) | 46/92 (50) | 0.715 | |

| Systemic hypertension | … | 56 (58.3) | 88 (80) | 0.001 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | … | 28 (29.2) | 48 (43.6) | 0.032 | |

| Atrial fibrillation | … | 21 (21.9) | 45 (40.9) | 0.003 | |

| Valve disease | … | 9 (9.4) | 17 (15.5) | 0.190 | |

| Coronary artery disease | … | 25 (26) | 34 (30.9) | 0.441 | |

| No. of cardiovascular risk factors | … | 1.5 (1–3) | 2 (2–4) | <0.0001 | |

| PAH type, no. (%) | |||||

| Idiopathic PAH | 23 (46) | 59 (61.5) | … | 0.222/0.874a | |

| Associated with connective tissue disease | 9 (18) | 19 (19.8) | … | ||

| Associated with congenital heart disease | 5 (10) | 6 (6.3) | … | ||

| Portopulmonary | 5 (10) | 5 (5.2) | … | ||

| PVOD | 2 (4) | 3 (3.1) | … | ||

| Other | 6 (12) | 4 (4.2) | … | ||

| NYHA functional class, no. (%) | |||||

| I | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 (0.9) | 0.003/0.043b | 0.051b |

| II | 15 (30) | 7 (7.3) | 16 (14.7) | ||

| III | 22 (44) | 59 (61.5) | 76 (68.8) | ||

| IV | 13 (26) | 29 (30.2) | 17 (15.6) | ||

| Clinical symptoms and signs | |||||

| Orthopnea, no. (%) | 3/28 (10.7) | 17/69 (24.6) | 23/74 (31.1) | 0.125/0.314 | 0.391 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 82 (75–98) | 80 (72–92) | 79 (69–89) | 0.247/0.517 | 0.085 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 128 (115–133) | 138 (120–158) | 147 (132–160) | 0.003/0.042 | 0.024 |

| Peripheral edema, no. (%) | 19 (38) | 42/95 (44.2) | 66 (60) | 0.472/0.908 | 0.020 |

| Six-minute walk test | |||||

| Distance, m | 276 (78–405) | 180 (96–276) | 180 (93–310) | 0.021/0.321 | 0.976 |

| Pretest SpO2, % | 97 (93–98) | 95 (91–98) | 96 (93–97) | 0.153/0.713 | 0.356 |

| Posttest SpO2, % | 94 (85–97) | 91 (86–97) | 93 (90–96) | 0.520 | 0.424 |

| BNP, ng/L | 274 (124–762) | 395 (101.4–1127) | 324 (185–817) | 0.280 | 0.467 |

| Medications, no. (%) | |||||

| Diuretics | 22 (44) | 62 (64.6) | 88 (80) | 0.017/0.335 | 0.013 |

| Warfarin | 15 (30) | 33 (34.4) | 49 (44.5) | 0.593/0.795 | 0.137 |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors | 5 (10) | 35 (36.5) | 41 (37.3) | 0.001/0.054 | 0.904 |

| Angiotensin II AT1 receptor blockers | 0 (0) | 13 (13.5) | 38 (34.5) | 0.006/0.999 | <0.0001 |

| Digoxin | 3 (6) | 9 (9.5) | 24 (21.8) | 0.471/0.553 | 0.016 |

| β-Blockers | 3 (6) | 21 (21.9) | 47 (42.7) | 0.014/0.179 | 0.001 |

| Statins | 4 (8) | 36 (37.5) | 61 (56) | 0.0001/0.007 | 0.008 |

All continuous variables are expressed as median (interquartile range). In the P value column for PAH–No CV versus PAH-CV, the second P value is after age adjustment. After Bonferroni correction, the statistical threshold is P ≤ 0.001. P values in boldface type indicate statistically significant differences. PAH: pulmonary arterial hypertension; CV: cardiovascular risk factors; PVH: pulmonary venous hypertension; BMI: body mass index; BSA: body surface area; PVOD: pulmonary venoocclusive disease; NYHA: New York Heart Association; SpO2: finger oxygen saturation; BNP: brain natriuretic peptide.

Refers to all types of PAH.

Refers to all World Health Organization functional classes.

Table 2.

Comparison of electrocardiographic, echocardiographic, and hemodynamic data

| P value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | PAH–No CV (n = 50) | PAH-CV (n = 96) | PVH-CV (n = 110) | PAH–No CV vs. PAH-CV | PAH-CV vs. PVH-CV |

| Electrocardiography | |||||

| Sinus rhythm, no. (%) | 49/49 (100)a | 72/93 (77.4)b | 61/105 (57.5)c | <0.0001/0.998 | 0.003 |

| RBBB, no. (%) | 5/49 (10.2) | 7/93 (7.5) | 5/105 (4.8) | 0.586/0.337 | 0.416 |

| R wave dominant in lead V1, no. (%) | 30/49 (61.2) | 37/93 (39.8) | 19/105 (18.1) | 0.015/0.424 | 0.001 |

| Right ventricular strain, no. (%) | 31/49 (63.3) | 40/93 (43) | 23/105 (21.9) | 0.022/0.541 | 0.001 |

| Right axis deviation, no. (%) | 31/49 (63.3) | 32/93 (34.4) | 15/105 (14.3) | 0.001/0.011 | 0.001 |

| PR interval, ms | 152 (143–161) | 164 (150–182) | 154 (140–179) | 0.006/0.045 | 0.110 |

| QRS duration, ms | 97 (84–108) | 94 (86–104) | 94 (84–106) | 0.607/0.845 | 0.934 |

| Echocardiography | |||||

| Left ventricular end-diastolic diameter, cm | 4.3 (3.8–4.6) | 4.2 (3.9–4.6) | 4.7 (4.2–5.1) | 0.901/0.678 | <0.0001 |

| Interventricular septal thickness, cm | 0.9 (0.7–1) | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 0.007/0.387 | 0.462 |

| Left ventricular posterior wall thickness, cm | 0.9 (0.8–1) | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | <0.0001/0.014 | 0.353 |

| E/E′ ratio | 5 (3.9–7.3) | 7.5 (5–11) | 9.1 (7–14) | 0.091/0.547 | 0.009 |

| RV/LV ratio | 1.35 (1.07–1.68) | 1.22 (0.84–1.5) | 0.92 (0.79–1.15) | 0.120/0.303 | <0.0001 |

| Peak velocity of tricuspid regurgitation, m/s | 4.2 (3.7–4.6) | 4.1 (3.6–4.5) | 3.7 (3.3–4.1) | 0.147/0.375 | <0.0001 |

| Right atrial volume, mL | 80 (65–100) | 105 (76–136) | 105 (78–124) | 0.029/0.507 | 0.713 |

| Left atrial diameter, cm | 3 (3–4) | 4 (3–4) | 5 (4–5) | 0.001/0.024 | <0.0001 |

| LAVI | 36 (26–47) | 44 (31–57) | 55 (38–70) | 0.046/0.921 | 0.001 |

| TAPSE, mm | 15 (11–19) | 15 (13–20) | 16 (13–21) | 0.608/0.587 | 0.803 |

| Right ventricular TDI S wave, cm/s | 9 (8.6–11) | 11 (9–12) | 9 (8–12) | 0.073/0.195 | 0.041 |

| Right ventricular Tei index | 0.7 (0.57–0.8) | 0.6 (0.47–0.74) | 0.5 (0.38–0.65) | 0.142/0.338 | 0.067 |

| Pericardial effusion, no. (%) | 9 (18) | 23 (24) | 9 (8.2) | 0.409/0.739 | 0.002 |

| Hemodynamics | |||||

| mPAP, mmHg | 51 (44–59) | 43 (33–56) | 41 (33–53) | 0.023/0.998 | 0.284 |

| LVEDP, mmHg | 8 (6–10) | 10 (8–13) | 18 (17–22) | 0.001/0.007 | |

| PAWP, mmHg | 10 (8–12) | 12 (9–15) | 21 (17–25) | 0.002/0.008 | |

| mRAP, mmHg | 7 (5–10) | 10 (7–14) | 15 (11–18) | 0.023/0.016 | <0.0001 |

| RVEDP, mmHg | 10 (6–14) | 10 (7–15) | 15 (9–18) | 0.602/0.196 | <0.0001 |

| Transpulmonary gradient, mmHg | 40 (32–47) | 34 (20–44) | 18 (12–28) | 0.006/0.372 | |

| Diastolic pulmonary pressure difference, mmHg | 22 (11–30) | 18 (9–27) | 2 (−3 to 11) | 0.248/0.375 | |

| Cardiac index | 2.2 (1.8–2.9) | 2.2 (1.9–2.8) | 2.1 (1.8–2.8) | 0.893/0.926 | 0.564 |

| Pulmonary vascular resistance, Wood units | 11 (6–15) | 8 (5–13) | 5 (3–8) | 0.039/0.732 | <0.0001 |

All continuous variables are expressed as median (interquartile range). In the P value column for PAH–No CV versus PAH-CV, the second P value is after age adjustment. After Bonferroni correction, the statistical threshold is P ≤ 0.001. P values in boldface type indicate statistically significant differences. PAH: pulmonary arterial hypertension; CV: cardiovascular risk factors; PVH: pulmonary venous hypertension; RBBB: right bundle branch block; RV/LV ratio: right ventricular basal end-diastolic/left ventricular basal end-diastolic diameter (in the 4-chamber view); LAVI: left atrial volume index; TAPSE: tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion; TDI: tissue Doppler imaging; mPAP: mean pulmonary arterial pressure; LVEDP: left ventricular end-diastolic pressure; PAWP: pulmonary arterial wedge pressure; mRAP: mean right atrial pressure; RVEDP: right ventricular end-diastolic pressure.

One patient had paced rhythm.

Two patients had paced rhythm, and in one case an electrocardiogram was not available.

Five patients had paced rhythm.

Response to treatment: survival analysis

Forty-three (86%) of 50 patients were started on PAH-targeted treatment in the PAH–No CV group, while 75 (78%) of 96 were started in the PAH-CV group. The mean follow-up time was 20 ± 11.3 months in the PAH–No CV group and 16.4 ± 10.9 months in the PAH-CV group (P = 0.290). Patients in the PAH–No CV group were 3.3 times more likely to show improvement on treatment than were patients in the PAH-CV group (odds ratio, 3.294 [95% confidence interval, 1.11–9.72]; P = 0.002 before and 0.027 after adjustment for age; Table 3). The difference in response to treatment was driven by less improvement in the PAH-CV group rather than more worsening. The number of CV risk factors did not significantly affect the response to PAH therapies. There was no difference between PAH-specific medications (monotherapy or combination therapy) prescribed in the two groups (Table 4).

Table 3.

Response to pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) drug therapy

| PAH–No CV group (n = 43) | PAH-CV group (n = 69) | P value for improvement vs. no improvement | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Improvement | 16 (37) | 11 (16) | 0.002/0.027a |

| No improvement | 27 (63) | 58 (84) | |

| Stable | 14 (33) | 31 (45) | |

| Worsening | 13 (30) | 27 (39) |

Data are no. (%). CV: cardiovascular risk factors.

After adjustment for age.

Table 4.

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) medications

| Medication | PAH–No CV (n = 43) | PAH-CV (n = 75) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors | 36 (84) | 62 (83) | 0.356 |

| Endothelin receptor antagonists | 21 (49) | 39 (52) | 0.289 |

| Prostacyclin analogues | 6 (14) | 14 (19) | 0.125 |

| Combination therapy | 19 (44) | 38 (51) | 0.176 |

Data are no. (%). CV: cardiovascular risk factors.

The mean follow-up time for survival analysis was 32.8 ± 16.3 months for the PAH–No CV group and 28.2 ± 13 months for the PAH-CV group. Over 3 years, there were 13 deaths (26%) and the mean survival time was 30 months (SE, 1.529) in the PAH–No CV group, while there were 34 deaths (35.4%) with a mean survival time of 28.7 months (SE, 1.119) in the PAH-CV group (P = 0.245). Over 5 years, there were 15 deaths (30%) and the mean survival time was 46.2 months (SE, 2.962) in the PAH–No CV group, while there were 38 deaths (39.5%) and the mean survival time was 42 months (SE, 2.290) in the PAH-CV group. The difference between the groups was not significant (P = 0.218).

PAH-CV group versus PVH-CV group

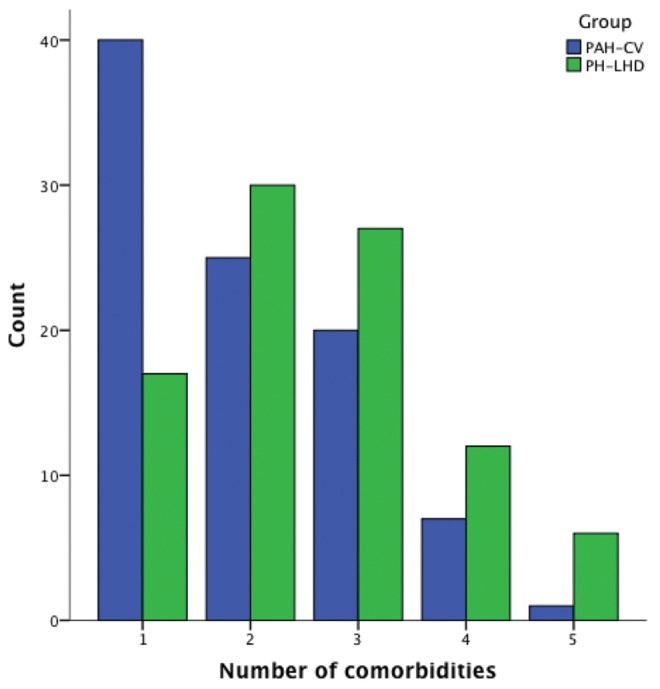

There was no significant difference in age and sex distribution between the PAH-CV and PVH-CV groups. Patients in the PVH-CV group had a significantly greater number of CV comorbidities (median, 2 vs. 1.5; P < 0.0001; Fig. 2). The two groups had no difference in symptoms, symptom severity, or clinical signs. Differences in ECG, echocardiogram, and hemodynamics are shown in Table 2.

Figure 2.

Number of cardiovascular comorbidities. Shown is the number of cardiovascular risk factors in the PAH-CV and PVH-CV groups. PAH: pulmonary arterial hypertension; CV: cardiovascular risk factors; PVH-CV: PH related to left heart disease with CV factors; PH: pulmonary hypertension; count: number of patients.

The mean follow-up time for the PVH-CV group was 26.2 ± 13 months. There were 29 deaths (26.3%), and the mean survival time was 47.7 months (SE, 2.330). Compared with the PAH-CV group, there was a trend toward better survival, although not statistically significant, in the PVH-CV group (P = 0.075).

Discussion

This is the first study to examine the response to PAH therapies according to the presence of CV risk factors related to left heart disease. This study showed that PAH patients with CV risk factors are less likely to respond well in terms of their symptom severity and exercise capacity 16 months after starting PAH drug therapies than are PAH patients without CV risk factors.

Data from COMPERA8 have shown that elderly idiopathic PAH patients respond less well to PAH therapies than younger ones. Age difference and less aggressive PAH treatment in the elderly group were mentioned as possible reasons for this difference. In our study, even after adjustment for age the less effective response to treatment in the older PAH group with CV comorbidities remained, while there was no difference in the drugs prescribed for the two groups.

Our study has shown that some of the phenotypic features of the PAH-CV group lie between those of the PAH–No CV and PVH-CV groups: compared with the PAH–No CV group, the PAH-CV group had a trend toward higher PAWP and LVEDP, which by definition are lower in the PVH-CV group. Increasing PAWP may increase right ventricular afterload and contribute to right ventricular dysfunction.24 In addition, the PAH-CV group had values for PVR and left atrial size between those of the PAH–No CV and PVH-CV groups.

One possible interpretation for the different response to PAH therapies in our study would be a possible deleterious effect of these drugs in the presence of left heart disease. The trials of intravenous epoprostenol and bosentan in patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction have shown either a negative or no effect on clinical outcomes.25-27 On the contrary, sildenafil in patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction has been shown to improve exercise capacity and hemodynamics.28,29 The recent LEPHT study (Study to Test the Effects of Riociguat in Patients with Pulmonary Hypertension Associated with Left Ventricular Systolic Dysfunction) with riociguat, a novel soluble guanylate cyclase stimulator, in patients with left systolic heart failure did not achieve its primary end point (decrease in mPAP) despite an improvement in other hemodynamic parameters (cardiac index, PVR), while it was not powered to detect any clinical outcomes in the study groups.30 In our study, patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction were excluded; however, PAH patients with CV risk factors may have masked left ventricular diastolic dysfunction. Some of the PAH-CV group characteristics, such as age, CV risk factors, heart failure symptoms, left ventricular ejection fraction of >50%, and dilated left atrium, meet the inclusion criteria used in randomized clinical trials in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).31-33 This suggests that the PAH-CV group overlapped or may have consisted of a subpopulation of patients with HFpEF who also have precapillary PH at rest. The relatively poor efficacy of PAH drugs in such patients would then be consistent with the findings of the RELAX (Evaluating the Effectiveness of Sildenafil at Improving Health Outcomes and Exercise Ability in People with Diastolic Heart Failure) trial, which showed that sildenafil failed to improve clinical status and exercise capacity in patients with HFpEF but not specifically with PH.34 Whether the natural history of some of the patients in the PAH-CV group is to develop postcapillary hemodynamics at a later stage is not clear. Our results would not be consistent, however, with the positive results of sildenafil in selected patients with left ventricular hypertrophy, HFpEF, and PH, although exercise capacity was not investigated in this study.35

The role of sildenafil has also been explored in the presence of CV comorbidities in animal models. In animals with diabetic cardiomyopathy, impaired glucose intolerance, triglyceridemia, and hypertensive cardiomyopathy, sildenafil has had a beneficial effect on left ventricular function.36-38 Although the effect on the function of the right ventricle is not known, in light of these studies the potential harmful effect of PAH drugs in the presence of CV comorbidities seems to be a less likely explanation.

If the drugs themselves are not responsible for the less good response of exercise capacity to them, then a more restrained myocardium might provide an explanation. In the PAH-CV group, the presence of CV risk factors may have caused coronary microvascular dysfunction, right ventricular ischemia (in addition to ischemia caused by increased afterload), and diastolic dysfunction, exactly as CV risk factors do in the left ventricle,39-41 resulting in right ventricular dysfunction and exercise limitation not responding to PAH drugs, which mainly act on pulmonary vasculature. Sildenafil, in additional to its beneficial effect on pulmonary vasculature, has been shown to have a positive direct effect on hypertrophied right ventricular myocardium by increasing its contractility in humans,42 but it was unable to prevent right ventricular diastolic dysfunction in animal models.43 Of note, sildenafil seems to play a beneficial role in microvascular coronary dysfunction of the left ventricle in women after a single dose, although its long-term effects are not known.44

The worse response to treatment did not lead to worse survival in our study. On the contrary, in COMPERA8 survival was significantly worse among elderly idiopathic PAH patients than among younger ones after adjustment for age. This difference could be attributed to the smaller size and the shorter time of follow-up of our population or to a much older population in COMPERA.

This study also examined whether the PAH-CV group shared some common characteristics with the patients with PVH-CV. The two groups had no age or sex differences. The PVH-CV group had a significantly greater prevalence of systemic hypertension and a trend toward more atrial fibrillation, while the total number of CV risk factors was significantly higher than in the PAH group (Fig. 2). The PVH-CV patients were less likely to have a dominant R wave on the ECG, while they had a larger left ventricle with a smaller RV/LV ratio, a more dilated left atrium, and a lower peak velocity of tricuspid regurgitation on the echocardiogram. Finally, on cardiac catheterization the PVH-CV patients had higher mean right atrial pressure and right ventricular end-diastolic pressure but lower PVR, with no difference in mPAP and cardiac index. These findings are consistent with other studies examining pulmonary venous hypertension45 and HFpEF46 with PH populations. In terms of survival, the patients with postcapillary PH had a trend toward better survival than the two PAH groups, which is consistent with the ASPIRE (Assessing the Spectrum of Pulmonary Hypertension Identified at a Referral Centre) registry.47

Study limitations

This is a single-center retrospective study, and for this reason we recognize that the findings require verification in other patient cohorts. Nevertheless, the findings concerning less treatment efficacy in the PAH-CV group are broadly consistent with registry data and add to an understanding of why some patients respond less well to drug therapy for PAH.

We chose to assess the response to treatment at the patient’s last hospital visit rather than at a set time to describe at least a medium-term rather than simply a short-term response. While this does mean we followed up patients after different periods on treatment, we did not do so within 3 months of commencing PAH drug treatment. Finally, we did not measure the blood levels of PAH drugs to check patients’ adherence to taking their medications or for unexpected drug interactions. It is possible that older patients taking more medications may not have taken their prescribed PAH drugs, and for this reason future studies should confirm that these drugs have been ingested.

Conclusions

This study shows that PAH patients with CV risk factors have a less satisfactory response to PAH drug therapies in terms of symptom severity and exercise capacity compared with PAH patients without CV risk factors and that this difference is not simply a result of age. With the diagnosis of PAH being made with increasing frequency in older patients, there is a need to further elucidate the mechanisms influencing the response to PAH drug therapies and to define the best management strategies in this population.

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.McLaughlin VV, Presberg KW, Doyle RL, et al; American College of Chest Physicians. Prognosis of pulmonary arterial hypertension: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2004;126(suppl 1):78S–92S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Barst RJ, Rubin LJ, Long WA, et al; Primary Pulmonary Hypertension Study Group. A comparison of continuous intravenous epoprostenol (prostacyclin) with conventional therapy for primary pulmonary hypertension. N Engl J Med 1996;334:296–301. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Rubin LJ, Badesch DB, Barst RJ, et al. Bosentan therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med 2002;346:896–903. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Galiè N, Ghofrani HA, Torbicki A, et al; Sildenafil Use in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (SUPER) Study Group. Sildenafil citrate therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med 2005;353:2148–2157. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Rich S, Dantzker DR, Ayres SM, et al. Primary pulmonary hypertension: a national prospective study. Ann Intern Med 1987;107:216–223. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Badesh DB, Raskob GE, Elliott G, et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: baseline characteristics from the REVEAL registry. Chest 2010;137:376–387. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Ling Y, Johnson MK, Kiely DG, et al. Changing demographics, epidemiology and survival of incident pulmonary arterial hypertension: results from the Pulmonary Hypertension Registry of the United Kingdom and Ireland. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012;186:790–796. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Hoeper MM, Huscher D, Ghofrani HA, et al. Elderly patients diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension: results from the COMPERA registry. Int J Cardiol 2013;168:871–880. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Galiè N, Hoeper MM, Humbert M, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Heart J 2009;30:2493–2537. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.McLaughlin VV, Archer SL, Badesch DB, et al. ACCF/AHA 2009 expert consensus on pulmonary hypertension: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on expert consensus documents and the American Heart Association developed in collaboration with the American College of Chest Physicians; American Thoracic Society; Inc.; and the Pulmonary Hypertension Association. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;53:1573–1619. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Russo C, Jin Z, Homma S, et al. Effect of obesity and overweight on left ventricular diastolic dysfunction: a community-based study in an elderly cohort. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57:1368–1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Fici F, Ural D, Tayfun S, et al. Left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in newly diagnosed untreated hypertensive patients. Blood Press 2012;21:331–337. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Patil VC, Patil HV, Shah KB, Vasani JD, Shetty P. Diastolic dysfunction in asymptomatic type 2 diabetes mellitus with normal systolic function. J Cardiovasc Dis Res 2011;2:213–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Cha Y, Redfield MM, Shen WK, Gersh BJ. Atrial fibrillation and ventricular dysfunction: a vicious electromechanical cycle. Circulation 2004;109:2839–2843. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Lund O, Flø C, Jensen FT, et al. Left ventricular systolic and diastolic function in aortic stenosis. Eur Heart J 1997;18:1977–1987. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Borg AN, Harrison JL, Argyle RA, Pearce KA, Beynon R, Ray SG. Left ventricular filling and diastolic myocardial deformation in chronic primary mitral regurgitation. Eur J Echocardiogr 2010;11:523–529. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Camm AJ, Kirchhof P, Lip GYH, et al. Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J 2010;31:2369–2429. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Bonow OR, Carabello B, Chatterjee K, et al. ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease. Circulation 2006;114(5):e84–e231. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Paulus WJ, Tschöpe C, Sanderson JE, et al. How to diagnose diastolic heart failure: a consensus statement on the diagnosis of heart failure with normal left ventricular ejection fraction by the Heart Failure and Echocardiography Associations of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2007;28:2539–2550. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.American Thoracic Society statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;166:111–117. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Bonderman D, Wexberg P, Martischnig AM, et al. A noninvasive algorithm to exclude pre-capillary pulmonary hypertension. Eur Resp J 2011;37:1096–1103. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Rudski LG, Lai WW, Afilalo J, et al. Guidelines for the echocardiographic assessment of the right heart in adults: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography endorsed by the European Association of Echocardiography, a registered branch of the European Society of Echocardiography and the Canadian Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2010;23:685–713. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Fremont B, Pacouret G, Jacobi D, Puglisi R, Charbonnier B, de Labriolle A. Prognostic value of echocardiographic right/left ventricular end-diastolic diameter ratio in patients with acute pulmonary embolism: results from a monocenter registry of 1,416 patients. Chest 2008;133:358–362. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Tedford RJ, Hassoun PM, Mathai SC, et al. Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure augments right ventricular pulsatile loading. Circulation 2012;125:289–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Califf RM, Adams KF, McKenna WJ, et al. A randomized controlled trial of epoprostenol therapy for severe congestive heart failure: the Flolan International Randomized Survival Trial (FIRST). Am Heart J 1997;134:44–54. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Packer M, McMurray J, Massie BM, et al. Clinical effects of endothelin receptor antagonism with bosentan in patients with severe chronic heart failure: results of a pilot study. J Card Fail 2005;11:12–20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Kalra PR, Moon JC, Coats AJ. Do results of the ENABLE (Endothelin Antagonist Bosentan for Lowering Cardiac Events in Heart Failure) study spell the end for non-selective endothelin antagonism in heart failure? Int J Cardiol 2002;85:195–197. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Lewis GD, Shah R, Shahzad K, et al. Sildenafil improves exercise capacity and quality of life in patients with systolic heart failure and secondary pulmonary hypertension. Circulation 2007;116:1555–1562. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Guazzi M, Samaja M, Arena R, Vicenzi M, Guazzi MD. Long-term use of sildenafil in the therapeutic management of heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;50:2136–2144. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Bonderman D, Ghio S, Felix SB, et al. Riociguat for patients with pulmonary hypertension caused by systolic left ventricular dysfunction: a phase II-b double blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging hemodynamic study. Circulation 2013;128:502–511. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Yusuf S, Pfeffer MA, Swedberg K, et al. Effects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and preserved left ventricular ejection fraction: the CHARM-Preserved trial. Lancet 2003;362:777–781. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Massie B, Carson P, McMurray J, et al. Irbersartan in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 2008;359:2456–2467. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Shah SJ, Heitner JF, Sweitzer NK, et al. Baseline characteristics of patients in the treatment of preserved cardiac function heart failure with an aldosterone antagonist trial. Circ Heart Fail 2013;6:184–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Redfield MM, Chen HH, Borlaug BA, et al. Effect of phosphodiesterase-5 inhibition on exercise capacity and clinical status in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2013;309:1268–1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Guazzi M, Vicenzi M, Arena R, Guazzi MD. Pulmonary hypertension in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a target of phosphodiesterase-5 inhibition in a 1-year study. Circulation 2011;124:164–174. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Cheng YS, Dai DZ, Ji H, et al. Sildenafil and FDP-Sr attenuate diabetic cardiomyopathy by suppressing abnormal expression of myocardial CASQ2, FKBP12.6, and SERCA2a in rats. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2011;32:441–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Behr-Roussel D, Oudot A, Compagnie SI, et al. Impact of a long-term sildenafil treatment on pressor response in conscious rats with insulin resistance and hypertriglyceridemia. Am J Hypertens 2008;21:1258–1263. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Ferreira-Melo SE, Yugar-Toledo JC, Coelho OR, et al. Sildenafil reduces cardiovascular remodeling associated with hypertensive cardiomyopathy in NOS inhibitor–treated rats. Eur J Pharmacol 2006;542:141–147. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Di Carli MF, Janisse J, Grunberger G, Ager J. Role of chronic hyperglycemia in the pathogenesis of coronary microvascular dysfunction in diabetes. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;41:1387–1393. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Galderisi M, Capaldo B, Sidiropulos M, et al. Determinants of reduction of coronary flow reserve in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus or arterial hypertension without angiographically determined epicardial coronary stenosis. Am J Hypertens 2007;20:1283–1290. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Paulus WJ, Tschöpe C. A novel paradigm for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: comorbidities drive myocardial dysfunction and remodeling through coronary microvascular endothelial inflammation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:263–271. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Nagendran J, Archer SL, Soliman D, et al. Phophodiesterase type 5 is highly expressed in the hypertrophied human right ventricle, and acute inhibition of phosphodiesterase type 5 improves contractility. Circulation 2007;116:238–248. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Borgdorff MA, Bartelds B, Dickinson MG, et al. Sildenafil enhances systolic adaptation, but does not prevent diastolic dysfunction, in the pressure-loaded right ventricle. Eur J Heart Fail 2012;14:1067–1074. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Denardo SJ, Wen X, Handberg EM, et al. Effect of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibition on microvascular coronary dysfunction in women: a Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) ancillary study. Clin Cardiol 2011;34:483–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Robbins IM, Newman JH, Johnson RF, et al. Association of the metabolic syndrome with pulmonary venous hypertension. Chest 2009;136:31–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Thenappan T, Shah SJ, Gomberg-Maitland M, et al. Clinical characteristics of pulmonary hypertension in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail 2011;4:257–265. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Hurdman J, Condliffe R, Elliot CA, et al. ASPIRE registry: assessing the spectrum of pulmonary hypertension identified at a referral centre. Eur Respir J 2012;39:945–955. [DOI] [PubMed]