Abstract

Gay and bisexual men disproportionately experience depression, anxiety, and related health risks at least partially because of their exposure to sexual minority stress. This paper describes the adaptation of an evidence-based intervention capable of targeting the psychosocial pathways through which minority stress operates. Interviews with key stakeholders, including gay and bisexual men with depression and anxiety and expert providers, suggested intervention principles and techniques for improving minority stress coping. These principles and techniques are consistent with general cognitive behavioral therapy approaches, the empirical tenets of minority stress theory, and professional guidelines for LGB-affirmative mental health practice. If found to be efficacious, the psychosocial intervention described here would be one of the first to improve the mental health of gay and bisexual men by targeting minority stress.

Keywords: stigma, minority stress, gay and bisexual men, cognitive behavioral therapy, mental health

Sexual minority individuals (i.e., individuals who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual) utilize mental health services more frequently than heterosexuals (Cochran, Sullivan, & Mays, 2003). However, relatively little is known about the type or efficacy of mental health services that reach this group (Cochran, 2001). Although cognitive behavioral treatments (CBT) represent one of the most widely studied and disseminated treatments for several mental health disorders, such as major depression and the anxiety disorders (Butler, Chapman, Forman, & Beck, 2006), uncovering how to effectively adapt CBT for members of diverse groups is a relatively recent endeavor (Barrera & Castro, 2006; Hwang, 2009; Lau, 2006). Determining how CBT should be adapted to effectively address the unique determinants of sexual minority individuals’ mental health remains largely unexplored.

Professional organizations clearly recommend that mental health interventions should be adapted to address the unique facets of sexual minority individuals’ mental health in a way that affirms clients’ lesbian, gay, or bisexual (LGB) identities (e.g., American Psychological Association, 2012; Institute of Medicine, 2011). Yet, until recently, no empirical framework specified possible intervention adaptation targets. However, recent research identifies several stress pathways responsible for sexual minority individuals’ elevated mental health problems compared to heterosexuals (Hatzenbuehler, 2009), thereby providing prime candidates for intervention adaptation targets. In fact, addressing such targets in an efficaciously adapted treatment would cohere with professional guidelines for LGB-affirmative practice (American Psychological Association, 2012) and represent the first empirical test of an LGB-affirmative mental health intervention (Cochran, 2001).

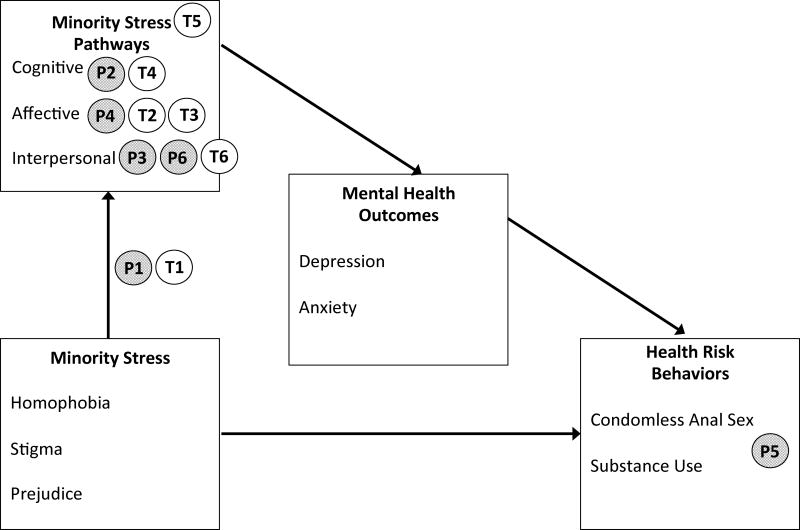

Minority stress theory provides the empirically supported framework for creating an LGB-affirmative adapted mental health intervention. Minority stress refers to the unique forms of stress that sexual minority individuals face because of their sexual orientation that occur over and above general life stress (Meyer, 2003; Meyer, Schwartz, & Frost, 2008). Compared to heterosexual individuals, sexual minority individuals are disproportionately exposed to victimization, discrimination, and peer and parental rejection against a societal backdrop of unequal access to the same opportunities afforded to heterosexual individuals, such as marriage, adoption, and employment non-discrimination (Balsam, Rothblum, & Beauchaine, 2005; Meyer, 2003). Cognitive, affective, and interpersonal pathways mediate the relationship between exposure to these minority stressors and mental health disorders (Hatzenbuehler, 2009). Specifically, minority stress disrupts these pathways to yield negative cognitive styles, diminished behavioral self-efficacy, emotion dysregulation, and social isolation, among others (see Figure 1). These mechanisms emerge early in sexual minority individuals’ development and serve as etiologic psychosocial vulnerabilities for mental health problems (Eisenberg & Resnick, 2006; Hatzenbuehler, McLaughlin, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2008; Safren & Heimberg, 1999).

Figure 1.

Minority stress pathway framework (see Hatzenbuehler, 2009).

Notes. Figure includes treatment principles (P) and techniques (T) guiding the intervention adaptation process.

-

P1Normalize mental health consequences of minority stress

-

P2Rework negative cognitions stemming from early and ongoing minority stress experiences

-

P3Empower gay and bisexual men to communicate openly and assertively across contexts

-

P4Validate gay and bisexual men’s unique strengths

-

P5Affirm healthy, rewarding expressions of sexuality

-

P6Facilitate supportive relationships

-

T1Consciousness-raising

-

T2Self-affirmation

-

T3Emotion awareness and acceptance

-

T4Restructuring minority stress cognitions

-

T5Decreasing avoidance (of cognitive, affective, and interpersonal experiences)

-

T6Assertiveness training

Cognitive behavioral therapy readily lends itself to addressing the cognitive, affective, and interpersonal pathways through which minority stress compromises mental health (Ellard, Fairholme, Boisseau, Farchione, & Barlow, 2010). CBT draws on principles of learning (Bouton, 2007) and cognition (Bandura, 1977) and specifically employs techniques such as motivational interviewing, self-monitoring, cognitive restructuring, mindfulness, and interoceptive and situational exposures to reduce these pathways. In addition to possessing strong theoretical and empirical support for reducing these pathways in the general population (Abramowitz, 1997; Barlow, Craske, Cerny, & Klosko, 1989; Borkovec & Costello, 1993; Foa, Keane, Friedman, & Cohen, 2008; Öst, 1989; Rodebaugh, Holaway, & Heimberg, 2004), CBT exercises based on principles of learning and cognition are particularly well suited to incorporating minority stress adaptations for several other reasons (Balsam, Martell, & Safren, 2006). First, CBT explores the functional nature of behavior in the context of current environmental contingencies and clients’ past learning history, such as minority stress experiences across development. Second, CBT draws on existing personal skills and resources, such as sexual minority clients’ resilience (Herrick, Stall, Goldhammer, Egan, & Mayer, 2013). Finally, CBT facilitates an objective restructuring of cognitions, such as chronic expectations of rejection, internalized homophobia, and contingent self-worth, arising from unsupportive or hostile environments (Meyer, 2003; Newcomb & Mustanski, 2010; Pachankis, Goldfried, & Ramrattan, 2008; Pachankis & Hatzenbuehler, 2013).

This paper describes the development of the first adaptation of an empirically supported treatment aimed at fostering gay and bisexual men’s coping with minority stress to reduce depression and anxiety. The primary goal of this study was to identify LGB-affirmative adaptations to an existing individual-administered CBT intervention to reduce the psychosocial mechanisms linking minority stress to depression and anxiety. Consistent with standard approaches for adapting interventions for diverse groups (e.g., Barrera & Castro, 2006; Hwang, 2009; Lau, 2006), the adaptation process involved iteratively integrating stakeholder feedback with a review of the empirical literature to uncover the unique principles and exercises that should inform the adapted intervention. This process yielded specific cognitive, affective, and interpersonal treatment targets and an adapted CBT intervention capable of reducing them.

This intervention was specifically adapted for sexual minority men given that sexual minority men face a relatively unique confluence of health threats compared to sexual minority women. For sexual minority men, minority stress and depression and anxiety combine with disproportionate exposure to childhood sexual abuse, sexual compulsivity, substance abuse, and HIV risk, creating a synergistic conglomerate of health threats. According to one theory of these interrelated health threats—syndemic theory—addressing any one of the health threats, such as mental health problems, should have the potential to mitigate the others, such as substance abuse and HIV risk behavior (Mustanski, Garofalo, Herrick, & Donenberg, 2007; Parsons, Grov, & Golub, 2012; Stall et al., 2003). Consequently, the intervention described here was created with the potential to break the cascade of mental and physical health threats emerging from early and ongoing minority stress exposure among sexual minority men. Because of the significant prevalence of HIV among gay and bisexual men (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013) and the strong links between minority stress, mental health problems, and HIV risk behavior (Safren, Reisner, Herrick, Mimiaga, & Stall, 2010), this intervention includes a complementary focus on reducing condomless anal sex among HIV-negative gay and bisexual men in addition to improving minority stress coping and reducing depression and anxiety.

Method

Participants

Expert Mental Health Providers

Twenty-one mental health providers with expertise in gay and bisexual men’s mental health provided input into the intervention adaptation process. Experts were identified through a search of publication databases (e.g., PsycINFO), professional leadership rosters (e.g., Society for the Psychological Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Issues of the American Psychological Association), and professional membership rosters (e.g., Study of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Issues Special Interest Group of the Association of Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies). A research assistant created a list of potential experts from these searches, counted each potential expert’s relevant publications, and performed an Internet search to determine if each person was currently practicing psychotherapy. Excluding the investigators of the present study, 46 experts were identified in this search who had published at least two journal articles or books related to gay and bisexual men’s mental health and who were preliminarily identified as currently providing mental health services to members of the LGB community.

Each of these 46 experts received an email confirming that they were currently in practice with gay and bisexual men and assessing their interest in participating in a 60-minute telephone interview. Six of these experts replied that they were not currently in practice. Nineteen either did not reply to the email or indicated that they could not complete the interview because of time constraints. The remaining 21 signed an online consent form and participated in a 60-minute telephone interview to gather suggested adaptations to an intervention aimed at reducing the negative mental health impact of minority stress among gay and bisexual men. Each participant received $75.00 for participating.

Participants indicated providing mental health services for a mean of 25.14 (SD = 10.72) years and providing services to gay or bisexual men for 20.26 (SD = 12.10) years. In addition to their expertise established through relevant publications and several years of practice, participants reported extensive involvement in LGB-related professional organizations, training, and mentoring. Eleven of the interviewed experts were male and 10 were female. Experts were located across 10 U.S. states, the District of Columbia, and Canada. Sixteen therapists possessed familiarity with CBT as ascertained through a question regarding professional background.

Gay and Bisexual Men

Twenty gay and bisexual men also provided input into the development of the adapted intervention. For inclusion in this study, these men had to report being over the age of 18, residing in New York City, being fluent in English, currently experiencing symptoms of depression and anxiety, being HIV-negative, and engaging in HIV risk behavior (i.e., at least one instance of condomless anal sex with any casual male partner or with an HIV-positive or status-unknown main or casual male partner). Gay and bisexual male participants in this study were recruited through advertisements posted to social and sexual networking websites and mobile applications (e.g., Adam4Adam, Facebook, Grindr) and in-person at gay community venues. Online advertisements directed participants to an online assessment that screened participants’ eligibility for several studies related to gay and bisexual men’s health. Participants who were screened in the field completed similar screening assessments on electronic tablets. Research assistants telephoned participants whose responses to screening questions indicated preliminary eligibility for the present study in order to further verify eligibility and schedule an in-person appointment. Current symptoms of depression and anxiety were assessed during the telephone screen with the four-item Brief Symptom Inventory – Screening scale (Lang, Norman, & Means-Christensen, 2009) adapted from the Brief Symptom Inventory (Derogatis, 2001). Participants responded to each of the four items using a five-point scale. A minimum cutoff of 2.5 on either the depression or anxiety scale was chosen as an inclusion criterion for this study in order to maximize sensitivity relative to specificity (Lang et al., 2009) and to ensure that participants who provided input into the intervention would be similar to gay and bisexual men who would ultimately receive the mental health intervention. New York City residence was required in order to develop the intervention within a local context, recognizing that the effectiveness of health interventions for stigmatized groups depends on understanding the community norms and social networks surrounding community members (Bernal & Sáez-Santiago, 2006; Rhodes, Singer, Bourgois, Friedman, & Strathdee, 2005). New York City is unique in being home to the largest, most diverse, and arguably oldest (Chauncey, 1995) gay community in the U.S. and the largest number of gay and bisexual men living with HIV in the country. Thus, the national perspective of the sample of expert mental health providers is complemented with the local perspective of the community who would ultimately receive the intervention.

Before completing the intervention adaptation interviews, participants completed a demographic questionnaire and measures of mental health, minority stress, HIV risk behavior, and previous mental health treatment experiences. Seventeen participants (85%) identified as gay, three (15%) as bisexual. Participants’ mean age was 30.80 (SD = 9.67). Eight participants (40%) indicated being Black or African American, seven (35%) indicated being white, three (15%) indicated being multiracial, and two (10%) indicated being Hispanic. Fifteen participants (75%) had completed at least some college. Compared to established norms (e.g., Crawford, Cayley, Lovibond, Wilson, & Hartley, 2011), participants reported very high levels of depression and anxiety. Specifically, participants’ mean score on the Center for Epidemiological Studies – Depression scale (Radloff et al., 1977) was 28.50 (SD = 13.09), which is in the 96th percentile of a general sample of adults. Participants’ score on the state form of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Spielberger, 1970) was 49.25 (SD = 11.67), the 91st percentile; their score on the trait form of this inventory was 54.30 (SD = 9.88), the 93rd percentile. Seven participants (35%) reported having sought help from a mental health provider in the past 12 months. Participants reported past-90 day condomless anal intercourse with casual partners (M = 3.35, SD = 2.13), HIV-positive casual or main partners (M = 1.00, SD = 1.92), and HIV status-unknown casual or main partners (M = 2.30, SD = 1.95). Participants completed the nine items of the Perceived Discrimination Scale (Kessler, Mickelson, & Williams, 1999) that assesses frequency of experiences with discrimination (e.g., being treated with less respect than others, being threatened or harassed) using a scale ranging from 1 = never to 4 = often. Participants indicated a moderate frequency (M = 2.28, SD = .55) of sexual orientation discrimination experiences.

Interview Questions

The adaptation interview was similar for both groups of participants (i.e., mental health providers and gay and bisexual men). Interview questions asked about common stressful experiences for gay and bisexual men; the impact of minority stress on depression, anxiety, and associated health risks; and adaptive and maladaptive strategies for coping with minority stress. Participants reviewed a brief outline of the planned intervention protocol and shared their general and specific adaptation suggestions.

Procedure

Standard mental health intervention adaptation methods were employed in order to adapt a CBT treatment to address the unique determinants of gay and bisexual men’s mental health and associated health risks (Barrera & Castro, 2006; Hwang, 2009; Lau, 2006). As described below, this process involved selecting a suitable intervention for adaptation and integrating stakeholder input with relevant theory, research, and clinical knowledge across several iterative steps. The adaptation approach sought to identify principles and exercises capable of overlaying the LGB-affirmative approach of minority stress theory onto the cognitive and behavioral tenets of the existing intervention.

Phase 1: Intervention Selection

We specifically searched for an intervention that would 1) be applicable across those mental health disorders that gay and bisexual men are disproportionately likely to experience compared to heterosexual men (e.g., depression, anxiety), 2) target the stress pathways that have been shown to be elevated in gay and bisexual compared to heterosexual men (e.g., emotion regulation difficulties, social isolation), and 3) include standard principles of learning and cognition in a treatment package lending itself to adaptation. The Unified Protocol for the Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders (Barlow et al., 2011) met all three of these criteria. The Unified Protocol draws upon established learning and cognitive theory to target the pathways through which stress confers mental and behavioral health risk. The Unified Protocol was therefore adapted in the proposed study to support gay and bisexual men’s adaptive coping with minority stress, thereby reducing associated depression, anxiety, and HIV risk behavior.

The Unified Protocol is an individually-administered treatment possessing empirical support for alleviating stress-sensitive mental health disorders (i.e., depression and anxiety) at their source in maladaptive emotion regulation habits, cognitive styles, self-efficacy, behavioral avoidance, and impulsivity (Barlow et al., 2011; Ellard et al., 2010; Farchione et al., 2012; Wilamowska et al., 2010. It changes these underlying vulnerabilities using motivational interviewing, interoceptive and situational exposure, cognitive restructuring, mindfulness, and self-monitoring exercises, grounded in empirically-supported cognitive-behavioral principles and developmental and affective neuroscience models of stress. Recent outcome data show significant 6-month reductions in anxiety and depression symptoms for 37 individuals with a principal (i.e., most interfering and severe) anxiety disorder diagnosis, otherwise recruited with few diagnostic exclusion criteria compared to individuals on a 16-week waitlist (Farchione et al., 2012). Individuals with diagnostically heterogeneous anxiety disorders also received benefit from earlier open trials of the Unified Protocol, with 85% achieving responder status at 6-month follow-up on principal diagnoses and 80% achieving responder status on comorbid disorders (Ellard et al., 2010).

Phase 2: Stakeholder Input

Members of the research team conducted structured individual interviews with 15 expert mental health providers and 12 gay and bisexual men who met the inclusion criteria described above in order to gather principles and exercises for adapting the Unified Protocol to specifically address minority stress pathways. Each interview lasted approximately 60 minutes and was audio-recorded and transcribed by three clinical psychology doctoral student research assistants. After transcription, the research assistants and principal investigator extracted all relevant text and generated a list of repeating ideas. To further summarize the data, two research assistants created a codebook and applied the codebook to all interviews, following the general approach recommended by Auerbach and Silverstein (2003) for analyzing qualitative data. Research assistants reviewed the first 15% of text together to create the codebook before applying the codebook to the remaining text with an interrater agreement of .93.

Phase 3: Manual Development

Members of the research team and an expert in qualitative data analysis reviewed the themes to derive general principles and exercises for reducing the minority stress pathways depicted in Figure 1. In discussing possible principles for guiding the intervention development, the team sought repeating themes that specified broad influences on gay and bisexual men’s mental health that could be addressed through an individually-administered psychotherapy. Exercises were created through reviewing themes specifying cognitive, affective, and interpersonal strategies that could reduce the mental health impact of minority stress and be integrated into the Unified Protocol’s CBT framework. Participants’ responses also contained recommendations for maximizing the appeal and relevance of this intervention. Many of these recommendations were used to infuse the Unified Protocol manual with minority stress examples and LGB-affirmative therapist guidance. The final result of this phase was a preliminary intervention manual guided by LGB-affirmative principles and composed of CBT-based exercises capable of reducing minority stress pathways.

Phase 4: Stakeholder Review

Six additional expert mental health providers and eight additional depressed and anxious gay and bisexual men were presented with a brief summary of the manual created in Phase 3. Their feedback on this summary was used to further adapt the manual. Participants in this phase were generally receptive to the content and structure of the adapted intervention and provided suggestions for further modification.

Phase 5: Manual Revision and Preliminary Trial

The remaining suggestions of the Phase 4 participants were incorporated into a final manual for the intervention, called ESTEEM: Effective Skills to Empower Effective Men, which is currently being testing for acceptability, feasibility, and preliminary efficacy in a randomized controlled waitlist trial with 60 gay and bisexual men who report symptoms of depression, anxiety, and associated health risks. The Results section below provides the number of participants (out of all 21 experts and 20 gay and bisexual men with anxiety and depression) who specified each theme used in adapting the protocol.

Results

The iterative approach described above yielded six principles and six exercises that merge the LGB-affirmative approach of minority stress theory with the CBT-based principles and exercises of the Unified Protocol. Principles broadly guide the delivery of intervention exercises and are closely aligned with the theoretical framework of the intervention (Castonguay & Buetler, 2006), in this case minority stress theory and general principles of learning and cognition (Bandura, 1977; Bouton, 2007). Exercises represent the intervention techniques intended to change the cognitive, affective, and interpersonal pathways through which minority stress operates to produce adverse health outcomes. Some of the exercises described here represent adaptations of existing Unified Protocol exercises; others represent additional exercises that, although not included in the Unified Protocol, are nonetheless consistent with its cognitive and behavioral principles. The text below describes the principles and exercises of the adaptation. Figure 1 superimposes these principles and exercises onto the minority stress model guiding the adaptation process. Table 1 summarizes the content of ESTEEM sessions.

Table 1.

ESTEEM Session Content and Outline

|

Intake Assessment Mental health assessment Minority stress assessment Substance use and sexual risk assessment |

|

Session 1: Motivation Enhancement Learn how ESTEEM can empower oneself to cope with stress and improve mental health Discuss pressing mental health issues Discuss the unique strengths that the client possesses as a result of being gay or bisexual |

|

Session 2: The Nature and Emotional Impact of Minority Stress Discuss how early and current minority stress can lead to anxiety, depression, and health risks Learn to identify the specific forms that minority stress takes Review current strategies for managing minority stress |

|

Session 3: Tracking Emotional Experiences Learn about emotions and their connection to minority stress Learn to observe emotional reactions to minority stress |

|

Session 4: Awareness of Minority Stress Reactions Discuss the ways that minority stress shapes behavior Learn to describe emotional reaction to minority stress in a mindful, present-focused way Learn about the relationship between minority stress and substance use |

|

Session 5: Cognitive Restructuring Connect minority stress to negative, maladaptive thinking patterns Identify thoughts driven by minority stress and learn to modify them |

|

Session 6: Emotion Avoidance Learn how avoiding strong emotions can lead to problematic behaviors Discuss the ways that minority stress might lead to avoidance of certain experiences Learn how emotion avoidance may manifest in substance use or avoiding close relationships |

|

Session 7: Emotion-Driven Behaviors Identify how minority stress and related emotions might lead to avoidance of certain experiences Discuss the influence of minority stress on sexual behavior Create a list of experiences that the client would like to stop avoiding |

|

Session 8: Behavioral Experiments Confront reminders of stressful events in order to increase tolerance of strong emotions Learn adaptive responses to minority stress including developing healthy relationships |

|

Session 9: Assertiveness Skills Training Learn how to assert oneself safely in the face of minority stress Develop effective ways to convey self-respect in stressful situations Learn how assertiveness in the context of substance use or sex can improve health |

|

Session 10: Relapse Prevention Review new cognitive, affective, and interpersonal coping strategies learned in ESTEEM Discuss how to apply the lessons learned in ESTEEM to future minority stress experiences |

Principles

Principle 1: Normalize Mental Health Consequences of Minority Stress

Both samples of participants consistently reported that minority stress plays a key role in gay and bisexual men’s mental health, consistent with empirical research findings (Meyer, 2003). Table 2 lists reactions to various minority stressors described by participants organized by the cognitive, affective, and interpersonal minority stress pathways of minority stress theory (Hatzenbuehler, 2009). Given the prominent relevance of minority stress to gay and bisexual men’s mental health, the first principle of ESTEEM encourages therapists to normalize gay and bisexual men’s depression and anxiety as an understandable minority stress response, as explicitly noted by six expert therapists we interviewed. This principle permeates the first four modules of ESTEEM (see Table 1), as these modules facilitate insight into the role of minority stress on clients’ mental health. This principle also heavily influences the cognitive restructuring module in helping gay and bisexual men make accurate attributions for the source of their distress, as explicitly suggested by nine of the interviewed experts.

Table 2.

Minority Stress Examples Provided By Interview Participants

|

Daily Minority Stress Cognitive: self-consciousness Affective: fear of rejection and victimization; fear of being scrutinized or “found out;” hypervigilance; sadness about lack of rights; holding in emotional reactions to discrimination Interpersonal: ambiguously rejecting signals; rejection from religious communities; others’ stereotypes of gay and bisexual men as HIV-positive, not masculine, not virtuous, not religious; avoidance of “straight” events |

|

Friendship/Peer Stress Cognitive: feeling like an outcast; distrust of new people; low self-worth and shame from early rejection; fixation on what other people think Affective: disclosure and concealment stress; loneliness; shame from early rejection; rumination Interpersonal: social isolation; feelings of hiding one’s true self, living a double life, putting on a show; strain on friendships for not being open; early experience of being different; early experience of bullying |

|

Romantic Relationship Stress Cognitive: fear of ending up alone; pressure to lead hetero-normative life; pressure to be in a relationship; being bisexual and not knowing whether to partner with a man or woman Affective: heightened threat perception in relationships; fears of contracting HIV; difficulty identifying and communicating emotions; sexual feelings toward men perceived as dangerous and shameful; resentment of being single; worries about public displays of affection Interpersonal: avoidance of romantic intimacy; suppressing romantic sentiments; difficulties communicating about HIV status; fleeting sexual encounters without lasting intimacy; sleeping with friends; negotiating sexual agreements with partners; unassertiveness in relationships |

|

Family and Developmental Stress Cognitive: not having a sense of control in adolescence Affective: sadness at family’s non-acceptance Interpersonal: lack of role models for leading a fulfilling life as a gay/bisexual man; feelings of letting parents down; early gender nonconformity; bullying; lack of parental acceptance; holidays bringing up family non-acceptance; family’s incorrect views about sexual orientation |

|

Gay Community Stress Cognitive: not being gay enough; pressure to attain high financial status; ageism; fitting in through substance use; rigid body standards; concern about penis size; focus on financial success, status, attractiveness; oppressive valuing of masculinity; distrust of masculinity Affective: escapism through substances; guilt after “hedonism;” seeking sex to reduce stress Interpersonal: strong pressure to self-label and fit into a gay community subgroup (e.g., bears); easy validation and companionship through sex; pressure not to label as bisexual; emphasis on hooking up; acceptability of substance use; community norms pose challenges to forming a long- term relationship; dishonesty about relationship status and HIV status |

|

Workplace Discrimination Cognitive: worries about bringing partner to work event Interpersonal: experiencing tokenism in the workplace (e.g., being a representative of all gay men); hiding gay-related accomplishments on resume |

Principle 2: Rework Negative Cognitions Stemming from Early and Ongoing Minority Stress Experiences

All gay and bisexual participants suggested that early and ongoing minority stress communicates that gay and bisexual men are deficient, inferior, or impaired. Twelve expert participants suggested that some gay and bisexual men internalize these messages, even outside of awareness (n = 3). Thus, these messages, although incorrect, could become ingrained ways of thinking about oneself across the lifespan if they are never held up to critical scrutiny. Negative self-views form a core part of depression and anxiety (Tangney, Wagner, & Gramzow, 1992), but can be replaced with more adaptive thinking patterns using CBT techniques (Dobson, 1989). Therefore, ESTEEM helps gay and bisexual men adopt a critical perspective on the inaccurate messages they may have internalized from minority stress experiences. This principle infuses the LGB-affirmative stance that characterizes the entire intervention, but is most explicitly communicated through the cognitive restructuring module.

Principle 3: Empower Gay and Bisexual Men to Communicate Openly and Assertively Across Contexts

Both groups of interviewees (16 gay and bisexual men, 11 experts) noted that minority stress operates to diminish gay and bisexual men’s ability to communicate openly and assertively across contexts. For example, early minority stress communicates that gay and bisexual men’s needs, desires, and preferences are invalid, which undermines their ability to articulate their needs later in development. Empirical research, in fact, outlines cognitive, affective, and interpersonal pathways, for example heightened sensitivity to rejection, arising from minority stress experiences and predicting unassertive communication (e.g., Pachankis, Goldfried, & Ramrattan, 2008). ESTEEM, therefore, explicitly supports gay and bisexual men’s ability to communicate openly and assertively across interpersonal contexts. This principle most explicitly guides the behavioral experiments and assertiveness skills training modules that seek to empower gay and bisexual men by lending a sense of agency and control in minority stress contexts.

Principle 4: Validate Gay and Bisexual Men’s Unique Strengths

As every participant noted, minority stress presents numerous challenges to young gay and bisexual men’s wellbeing, often from an early age. However, some expert therapists (n = 6) were quick to note that the majority of gay and bisexual men show powerful resilience in coping with these challenges, including demonstrating pride, sexual and social creativity, community building, and social activism, which is consistent with other research findings (e.g., Herrick et al., 2013). These personal and community strengths can provide the building blocks for creative and successful navigation of challenges across the lifespan. ESTEEM, therefore, draws on gay and bisexual men’s unique strengths to facilitate resilience in the face of ongoing minority stress. From the beginning of treatment, clients are asked to articulate the unique strengths they possess as gay and bisexual men that they can draw upon as they embark on subsequent exercises to reduce their depression and anxiety. In this way, this principle informs minority stress coping throughout all ESTEEM modules.

Principle 5: Affirm Healthy, Rewarding Expressions of Sexuality

As noted above, 12 experts noted that as a result of minority stress, gay and bisexual men might internalize notions about themselves as shameful, undesirable, and incapable of forming a loving relationship. These notions might pose a barrier to forming a healthy sexuality (Renaud & Byers, 2001). As nearly every participant (19 gay and bisexual men, 17 experts) noted, negative beliefs about one’s sexual self as shameful, inferior, or not deserving or capable of love can lead to engaging in sex under the influence of substances, not asserting one’s preferences in sexual encounters, or engaging in sex that feels out of control. Thus, ESTEEM helps gay and bisexual men embrace sex with other men as an important component of overall health. Many of the examples and exercises (e.g., cognitive restructuring, behavioral experiments) throughout the ESTEEM manual ask therapists to consider the degree to which minority stress may be impacting clients’ sexuality and to assist clients in formulating rewarding ways of expressing their sexuality. These exercises also guide the therapist to assess communication styles and the role of substance use in sexual expression in order to help clients consider healthy expressions of sexuality.

Principle 6: Facilitate Supportive Relationships

Minority stress can contribute to a sense of exclusion across the lifespan. Several participants (12 gay and bisexual men, 4 experts) noted that many gay and bisexual men also find the gay community to be inaccessible or inhospitable in its focus on masculinity, financial success, youth, and attractiveness. As a result of these experiences, gay and bisexual men may have difficulties developing close relationships and forming strong community ties. Empirical research suggests that poor social support among gay and bisexual men is associated with several negative mental health consequences (e.g., Hatzenbuehler, Nolen-Hoeksema, and Dovidio, 2009; Safren & Heimberg, 1999). Therefore, ESTEEM helps gay and bisexual men build supportive relationships to steel their wellbeing against minority stress. This principle is most clearly articulated in the emotion-driven behaviors and behavioral experiments modules of ESTEEM that assist the client in approaching previously avoided situations, including the formation of supportive relationships within and outside of the gay community.

Techniques for Implementing Principles

Technique 1: Consciousness-raising

Several expert participants (n = 7) recommended raising awareness about the existence of minority stress and the burden it places on gay and bisexual men’s mental health, consistent with Principle 1 of normalizing the mental health consequences of minority stress. Therefore, ESTEEM includes a consciousness-raising module that increases gay and bisexual men’s awareness of the mental health impact of minority stress. In this module, clients will review their personal minority stress experiences, receive feedback from minority stress intake assessments, and track their minority stress encounters between sessions. This exercise is consistent with the psychoeducational and motivational modules of the Unified Protocol, in that examining and tracking the nature and function of minority stress can serve to raise awareness about a potentially unacknowledged mental health burden and thereby serve as a source of motivation to address this burden. Consciousness-raising exercises occupied an important historical role in CBT interventions focused on helping members of other disenfranchised groups take steps toward empowering themselves against unjust societal contexts (e.g., Lange & Jakubowski, 1976), consistent with feminist psychotherapy models (e.g., Barrett et al., 2005). Consciousness-raising exercises are expected not only to facilitate insight into the existence of minority stress, but also to help shift attributions about the source of personal distress away from the client as a gay or bisexual man toward the unfair burdens of minority stress, a recommended strategy for coping with minority stress (Crocker & Major, 1989).

Technique 2: Self-affirmation

Most depressed and anxious gay and bisexual interviewees (n = 16) suggested that minority stress erodes self-worth through both direct (e.g., discrimination) and indirect (e.g., gay community exclusion) means. Therefore, consistent with Principle 4 of validating gay and bisexual men’s unique strengths, ESTEEM includes a modified version of a self-affirmation exercise aimed at increasing gay and bisexual men’s resilience against minority stress. This adapted exercise asks clients to watch a brief video clip of a gay or bisexual man discussing his experiences with minority stress. Clients are then instructed to write for 15 minutes, drawing on their personal experiences to advise the man in the video how best to cope with minority stress. In this way, this self-affirmation exercise asks clients to explicitly articulate their potentially latent personal coping resources. By generating coping advice for another gay or bisexual man, clients may be more likely to remember and follow this advice themselves. This type of “saying-is-believing” exercise has been shown to foster a sense of belonging and improve health among other marginalized groups (e.g., Walton & Cohen, 2011) and is consistent with findings from therapeutic writing exercises aimed at helping gay and bisexual men cope with minority stress (i.e., Pachankis & Goldfried, 2010).

Technique 3: Emotion Awareness and Acceptance

Most depressed and anxious gay and bisexual interviewees (n = 14) expressed strong willingness to better understand and cope with their emotions. Nearly every expert provider (n = 19) likewise suggested that many of their gay and bisexual clients experience emotion regulation difficulties (see Table 2). As described by expert providers, these difficulties stem from past and present environments that invalidate clients’ sexual orientation and possible gender nonconformity. Improving emotion regulation skills is consistent with empirical literature showing that sexual minorities demonstrate poorer emotion awareness and more rumination about their negative emotions than heterosexuals from an early age (e.g., Hatzenbuehler, McLaughlin, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2008). Therefore, the Unified Protocol emotion regulation exercises were modified in ESTEEM to help gay and bisexual men track their emotional reaction to minority stressors between sessions, consider the emotional influence of past and present invalidating environments, and practice mindfulness in response to minority stress. For example, clients will watch a brief video of individuals displaying prejudiced attitudes and then mindfully describe their emotional experience of these events. These exercises teach clients to recognize their emotional response to minority stress in preparation for enacting adaptive, empowering responses in subsequent sessions, consistent with Principle 1 (normalizing mental health consequences of minority stress) and Principle 3 (empowering assertive communication).

Technique 4: Restructuring Minority Stress Cognitions

As noted above, all gay and bisexual participants we interviewed and 12 expert providers noted that minority stress powerfully shapes gay and bisexual men’s cognitive styles, including beliefs about their selves, their world, and their future possible selves, as depicted in Table 2 and consistent with previous research (e.g., Hatzenbuehler et al., 2009; Newcomb & Mustanski, 2010; Pachankis, Goldfried, & Ramrattan, 2008; Pachankis & Hatzenbuehler, 2013). Therefore, consistent with Principle 2 of reworking negative cognitions stemming from minority stress, the cognitive restructuring exercises of the Unified Protocol (e.g., thought recording) were modified in ESTEEM to help clients understand their reactions to minority stress, the ways that minority stress can be directed toward oneself in the form of negative opinions about oneself and other gay men (e.g., internalized homophobia), and restructure maladaptive thought processes that may arise from past or current forms of minority stress. These adaptations draw upon internalized homophobia reduction research (Lin & Israel, 2012) and qualitative investigations into gay and bisexual men’s cognitive coping (Madsen & Green, 2012). The ESTEEM manual instructs therapists to employ these adapted exercises against an LGB-affirmative treatment backdrop that recognizes that maladaptive cognitions might have previously represented functional adaptations to hostile environments for many gay and bisexual clients. For example, some gay men’s disproportionate fears of negative evaluation might have developed within the context of early minority stress and, in fact, might have served to protect them from hostility (Pachankis & Goldfried, 2006). However, for clients who find themselves in more supportive present environments, this tendency may have outlived its original usefulness and may be contributing to depression and anxiety. By highlighting the current mismatch between expectation and environment, therapists can help clients revise interpersonal schemas driving poor mental health.

Technique 5: Decreasing Avoidance

Exposure exercises are efficacious in reducing symptoms of major depression (Jacobson et al., 1996) and anxiety disorders (Abramowitz, 1997; Barlow, Craske, Cerny, & Klosko, 1989; Borkovec & Costello, 1993; Foa, Keane, Friedman, & Cohen, 2008; Öst, 1989; Rodebaugh, Holaway, & Heimberg, 2004) through encouraging clients to approach distressing stimuli and habituate to aversive states of arousal. Recognizing that avoidance of cognitive, affective, and interpersonal experiences perpetuates poor mental health, the Unified Protocol includes exposure exercises that facilitate insight into the client’s avoidance patterns and attempt to reduce these tendencies. Because these avoidance patterns also represent key pathways through which minority stress yields depression, anxiety, and associated health risk behavior (see Figure 1), ESTEEM adapts the Unified Protocol’s exposure techniques to specifically facilitate awareness of common avoidance behaviors experienced by gay and bisexual men (listed in Table 2), consistent with several principles guiding the development of ESTEEM (i.e., Principle 3: communicating assertively; Principle 5: affirming sexuality; Principle 6: facilitating supportive relationships). The ESTEEM manual directs clients to assess personal avoidance reactions, locate their possible origin in various minority stressors, and utilize CBT exercises to break the avoidance pattern (see Table 3). Expert interviewees recommended exercises such as building supportive connections to the gay community (n = 11), asserting one’s needs (n = 10), and replacing substance use with more prosocial behavior (n = 17). Although exposure exercises for minority stress have not been previously examined in a randomized controlled trial, several case studies document the utility of these exercises for gay and bisexual men (e.g., Glassgold, 2009; Kaysen, Lostutter, & Goines 2005; Safren & Rogers, 2001).

Table 3.

Example Avoidance Behaviors Originating in Minority Stress and Alternative Behaviors

| Avoidance Behaviors | Possible Minority Stress Origin | Alternative Behaviors |

|---|---|---|

| Avoiding romantic connections with other men | Internalized homophobia | Establishing a profile on a gay dating website, going on dates |

| Perfectionistic behavior at work or home | Early and ongoing experiences of actual or feared rejection, contingent self-worth | Leaving things untidy or unfinished |

| Avoiding heterosexual men | Early and ongoing experiences of actual or feared rejection, concealment | Asking a heterosexual co- worker out to lunch |

| Social withdrawal, escaping social situations | Fears of rejection, concealment, past victimization | Staying in a situation and approaching people; smile or produce non-fearful facial expressions |

| Not asserting one’s needs, opinions, preferences | Fears of rejection, past victimization | Assertively stating one’s needs, opinions, preferences |

| Using substances during sex | Fears of rejection, internalized homophobia | Having sober sex |

| Hypervigilance | Fears of rejection, concealment, past victimization | Focus attention on specific task at hand; meditation; relaxation |

Technique 6: Assertiveness Training

Ten expert interviewees suggested that minority stress produces unassertive interpersonal behavior (see Table 2). Research additionally locates the cause of unassertiveness in minority stress (Pachankis et al., 2008) and specifies at least one negative health outcome of unassertiveness among gay and bisexual men, namely difficulties negotiating condom usage (Hart & Heimberg, 2005). Therefore, ESTEEM adds a behavioral skills training module to the Unified Protocol that is specifically focused on assertiveness. This module adapts standard assertiveness approaches (e.g., Lange & Jakubowski, 1976) for use in situations related to minority stress, both directly (e.g., overhearing a prejudiced comment) and indirectly (e.g., asserting condom usage, declining substances, forming new relationships). While not previously tested for efficacy, the suitability of minority stress assertiveness training has been documented in case reports (Glassgold, 2009) and in pilot studies (Pachankis, 2009) and is consistent with Principle 3 (empowering gay and bisexual men to communicate assertively) and Principle 6 (facilitating supportive relationships).

General Considerations

The adaptation interviews generated several recommendations that were subsequently incorporated throughout ESTEEM. A primary suggestion from several expert providers (n = 6) concerned how heavily to adopt a minority stress framework in conceptualizing clients’ mental health problems. In fact, a few expert interviewees (n = 3) suggested that minority stress may not represent the modal explanation for mental health concerns among gay and bisexual men and that mental health determinants for sexual minority clients are as heterogeneous as they are for heterosexual clients. In fact, the majority of sexual minority clients do not seek treatment for reasons ostensibly related to their sexual orientation (Jones & Gabriel, 1999) and focusing on a client’s sexual orientation when sexual orientation is not the presenting issue represents a form of non-LGB-affirmative treatment (e.g., Eubanks-Carter, Burckell, & Goldfried, 2005; Pachankis & Goldfried, 2004). Nonetheless, nearly all gay and bisexual participants with depression and anxiety we interviewed (n = 18) expressed enthusiasm for a treatment grounded in minority stress theory and readily saw its potential to improve mental health. One of the two remaining participants noted that he was too busy for therapy and, another, that he already engages in similar exercises on his own. To avoid focusing on minority stress at the expense of acknowledging clients’ resilience, the ESTEEM manual clearly specifies that a minority stress conceptualization should only follow a thorough assessment of clients’ past and ongoing experiences of minority stress while explicitly reinforcing clients’ existing strengths throughout treatment. Treatment for clients for whom a minority stress conceptualization does not initially fit can proceed along standard evidence-based lines while being prepared to reconsider the relevance of minority stress if it becomes relevant over the course of treatment.

Eight expert therapists suggested that ESTEEM therapists ought to deliver the modules flexibly depending on client symptom presentation. While the sequence of the ESTEEM sessions represents a logical approach for most presenting concerns (see Table 1), the ESTEEM manual cautions therapists to approach the session sequence flexibly. For example, motivation enhancement can be revisited at any point during which the client’s motivation wanes. Further, for clients who experience severe symptoms of depression, such as avoidance of essential activities, the therapist may wish to implement behavioral experiments sooner in the treatment than currently suggested in order to increase upfront positive reinforcement and motivation. Still other clients may need to spend extra time on cognitive restructuring before moving onto behavioral experiments. While the sequence of sessions outlined in the therapist manual was chosen to benefit the prototypical client presenting for ESTEEM treatment, flexibility is encouraged in indicated cases. Nevertheless, therapists are advised to implement the primary components of all modules at some point over treatment given that they form a unified package.

All interviewees shared their perspective on preferred therapist characteristics. While the majority (n = 14) of the depressed and anxious gay and bisexual interviewees indicated that they would prefer a gay or bisexual male therapist, fewer expert mental health providers (n = 7) suggested that therapists delivering this intervention need to be gay or bisexual men, while relatively more (n = 10) suggested that they should possess LGBT-specific knowledge. All expert providers (n = 21) suggested that therapists delivering ESTEEM should adopt an affirmative therapeutic stance, consistent with empirical research (e.g., Burckell & Goldfried, 2006) and professional guidelines (American Psychological Association, 2012). Interviewees suggested that therapists who deliver ESTEEM must be comfortable using the therapeutic relationship as a model for healthy relationships (n = 4 experts) and possess a general therapeutic style marked by flexibility (n = 11 experts), self-awareness (n = 6 gay and bisexual men, n = 3 experts), humor (n = 1 gay and bisexual man, n = 4 experts), confidence (n = 4 gay and bisexual men), and patience (n = 2 gay and bisexual men, n = 2 experts). Some expert interviewees (n = 4) noted that members of the LGB community who deliver ESTEEM must take care to recognize the impact of minority stress on their own lives and its ability to insidiously impact treatment.

Five interviewees also suggested that the adapted treatment must take clients’ multiple identities into account to avoid solely focusing on sexual orientation at the expense of acknowledging more relevant identities or the synergistic intersection of other identities with one’s sexual orientation (das Nair & Butler, 2012). For example, some clients from racial/ethnic minority backgrounds may be readily familiar with the influence of social marginalization on their mental health as a result of their racial/ethnic identity development and may find unique sources of support within LGB communities of color that are unavailable from predominantly white LGB communities or their natal communities. In the way that it understands sexual orientation as one facet of an individual’s identity, ESTEEM adopts the affirmative stance encouraged in professional guidelines (e.g., American Psychological Association, 2012) and clinical handbooks (e.g., Ritter & Terndrup, 2002). Finally, experts (n = 8) noted that the language of minority stress theory, including the term “minority stress” itself, ought to be modified to be maximally comprehensible and relevant to clients’ experiences. Thus, therapists are encouraged to focus on the specific stressors reported by gay and bisexual men during intake and throughout the case conceptualization process and to avoid technical terms or jargon.

Discussion

This paper describes the adaptation of an empirically supported mental health intervention for gay and bisexual men. This intervention represents one of the first to specifically target the effects of minority stress to reduce depression, anxiety, and related health risks. Given the interrelated health conditions affecting gay and bisexual men and the key role of depression and anxiety in perpetuating health risk behaviors such as substance use and condomless anal intercourse (Stall et al., 2003), a psychosocial intervention capable of alleviating these conditions at their source in minority stress can potentially impact multiple, related aspects of gay and bisexual men’s health (Safren, Reisner, Herrick, Mimiaga, & Stall, 2010). Drawing on intervention adaptation methods employed for other minority groups (Barrera & Castro, 2006; Hwang, 2009; Lau, 2006), this study utilized an iterative process that integrated stakeholder feedback with a review of the empirical literature and professional guidelines. The resulting intervention, ESTEEM: Effective Skills to Empower Effective Men, is currently being pilot tested for acceptability, feasibility, and preliminary efficacy in an ongoing randomized waitlist controlled trial with 60 gay and bisexual men who report symptoms of depression, anxiety, and associated health risks.

The principles of ESTEEM, uncovered through interviews with 41 stakeholders, align with standard cognitive and behavioral principles (Goldfried & Davison, 1994) and minority stress theories (Hatzenbuehler, 2009; Meyer, 2003). CBT seeks to facilitate insight into the relationship among thoughts, emotions, and behaviors; to reduce negative thinking styles; to increase one’s ability to tolerate negative emotions; and to engage in new behavior that may have been previously avoided because of maladaptive thoughts, emotions, or behaviors. ESTEEM capitalizes on these principles to target the cognitive, affective, and interpersonal pathways through which minority stress impairs mental health. Specifically, as suggested by interviewees, ESTEEM might help clients understand the impact of minority stress on their thoughts, feelings, and behaviors (Principle 1, Technique 1, Technique 3); reduce the negative thinking styles that emerge from minority stress (Principle 2, Technique 4); adopt an empowering stance toward the negative mental health effects of minority stress by drawing on unique strengths developed in response to early and ongoing minority stress (Principle 3. Principle 4, Technique 2); and engage in new behaviors, including healthy expressions of sexuality and supportive relationships (Principle 5, Principle 6, Technique 5, Technique 6).

ESTEEM follows recent professional guidance and practical suggestions for delivering LGB-affirmative treatment (e.g., American Psychological Association, 2012; Drescher, 2001; Bieschke, Perez, DeBord, 2006; Martell, Safren, & Prince, 2004; Ritter & Terndrup, 2002). The principles of ESTEEM locate the ultimate source of sexual orientation mental health disparities in minority stress, while recognizing the potential for individual agency and resilience to generate successful coping against minority stress (Meyer, 2003). While structural interventions can reduce minority stress at its source through the creation of affirmative workplaces (Waldo, 1999), schools (Russell et al., 2001), families (Ryan, 2010), religious institutions (Hatzenbuehler, Pachankis, & Wolff, 2012), and social policies (Hatzenbuehler, 2010), psychosocial interventions capable of reducing the cognitive, affective, and interpersonal pathways through which minority stress operates also have the potential to improve mental health. CBT exercises are particularly well suited to LGB-affirmative mental health treatment in that they recognize the social environmental determinants of many mental health problems and enlist existing personal strengths against minority stress pathways (Balsam, Safren, & Martell, 2006).

ESTEEM complements existing psychosocial treatments that possess efficacy for reducing health-risk behaviors among sexual minority men. These interventions target multiple behavioral health outcomes, such as substance use (Pachankis, Lelutiu-Weinberger, Golub, & Parsons, 2013; Parsons, Lelutiu-Weinberger, Botsko, & Golub, in press), HIV medication adherence (Carrico et al., 2006; Horvath et al., 2013), and HIV-risk behavior (Mustanski, Garofalo, Monahan, Gratzer, & Andrews, 2013), using various modalities (e.g., individual psychotherapy, online peer support), and techniques (e.g., stress management). Still, none of these interventions explicitly focuses on enhancing minority stress coping to improve health. Thus, ESTEEM is expected to complement these existing interventions by targeting an established source of mental and physical health disparities related to sexual orientation (Lick, Durso, & Johnson, 2013; Meyer, 2003) that is currently unaddressed in existing psychosocial interventions.

In addition to establishing the acceptability, feasibility, and preliminary efficacy of the ESTEEM intervention, future tests of ESTEEM ought to compare its efficacy against that of existing interventions aimed at improving the syndemic health conditions adversely affecting gay and bisexual men. Because ESTEEM addresses mental health, sexual health, and substance use using a LGB-affirmative minority stress framework, future research can examine whether this integrated package improves health outcomes, such as HIV risk behavior, more so than targeting any of these factors in isolation. Additionally, employing a dismantling design, the efficacy of the ESTEEM modules can be tested in isolation against each other in order to determine which of these components yields the greatest impact in improving depression, anxiety, and associated health risks. A further question involves whether the adaptation approach applied here can be effectively applied to other empirically supported treatments, such as interpersonal therapy (Weissman & Klerman, 1994) or emotion-focused therapy (Greenberg, 2002), that lend themselves to other mechanisms underlying gay and bisexual men’s mental health potentially not addressed by ESTEEM. Group-based treatments (e.g., Heimberg & Becker, 2002) might represent particularly suitable adaptation platforms given that ESTEEM principles encourage assertive communication, validation of gay and bisexual men’s strengths, and building social support. Finally, although some ESTEEM components, such as the focus on reducing condomless anal sex, are particularly suited to gay and bisexual men, future explorations ought to consider how the principles and exercises of ESTEEM can best address the specific health needs of sexual minority women.

In conclusion, the adapted intervention described here, created through close review of stakeholder input, can potentially alleviate the multiple mental and physical health concerns facing sexual minority men. This intervention specifically empowers gay and bisexual men with evidence-based skills suitable for coping with the cognitive, affective, and interpersonal consequences of minority stress. This intervention infuses an existing empirically supported intervention (Ellard et al., 2010; Wilamowska et al., 2010) with LGB-affirmative treatment principles and exercises suggested by gay and bisexual men and expert mental health providers. These principles and exercises normalize the mental health consequences of minority stress, instill self-empowering cognitions, encourage assertive communication, strengthen personal resilience, and promote close relationships and rewarding sexual expression. Because the intervention targets one of the primary sources of gay and bisexual men’s interrelated psychosocial health threats, the skills it imparts can potentially generalize across contexts to improve the overall health of gay and bisexual men. Further, because it packages the collective wisdom of people most familiar with the mental health concerns of gay and bisexual men, it maximizes the likelihood of demonstrating appeal and efficacy in subsequent trials.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by a research grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (R34-MH096607; John E. Pachankis).

I would like to acknowledge the contributions of the collaborating investigators on this project (Jeffrey Parsons, Steven Safren, Mark Hatzenbuehler, Sarit Golub) and the ESTEEM research team (Laura Bernstein, Aliza Boim, Indiana Buttenwieser, Kathryn Davis, Luis Nobrega, Fran Ferayorni, Lara Friedrich, Ethan Fusaris, Zak Hill-Whilton, Ruben Jimenez, Erica Kestenbaum, Alexa Michl, Brett Millar, Rachel Proujansky). I also thank Carl Auerbach for his input on the qualitative analyses. Finally, I thank the participants who volunteered their time for this study.

Footnotes

The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Abramowitz JS. Effectiveness of psychological and pharmacological treatments for obsessive-compulsive disorder: A quantitative review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65(1):44–52. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.65.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach CF, Silverstein LB. Qualitative data: An introduction to coding and analysis. New York University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. Guidelines for psychological practice with lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients. American Psychologist. 2012;67:10–42. doi: 10.1037/a0024659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrico AW, Antoni MH, Durán RE, Ironson G, Penedo F, Fletcher MA, Schneiderman N. Reductions in depressed mood and denial coping during cognitive behavioral stress management with HIV-positive gay men treated with HAART. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2006;31(2):155–164. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3102_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsam KF, Rothblum ED, Beauchaine TP. Victimization over the life span: A comparison of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and heterosexual siblings. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73(3):477–487. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsam KF, Martell CR, Safren SA. Affirmative cognitive-behavioral therapy with lesbian, gay, and bisexual people. In: Hays PA, Iwamasa GY, editors. Culturally responsive cognitive-behavioral therapy: Assessment, practice, and supervision. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2006. pp. 223–243. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review. 1977;84:191–215. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Farchione TJ, Fairholme CP, Ellard KK, Boisseau CL, Allen LB, Ehrenreich-May J. Unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: Therapist guide. New York: Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Craske MG, Cerny JA, Klosko JS. Behavioral treatment of panic disorder. Behavior Therapy. 1989;20(2):261–282. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(89)80073-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M, Castro FG. A heuristic framework for the cultural adaptation of interventions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2006;13(4):311–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2006.00043.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett SE, Chin JL, Diaz LC, Espin O, Greene B, McGoldrick M. Multicultural feminist therapy: Theory in context. Women & Therapy. 2005;28(3–4):27–61. doi: 10.1300/J015v28n03_03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal G, Sáez-Santiago E. Culturally centered psychosocial interventions. Journal of Community Psychology. 2006;34(2):121–132. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bieschke KJ, Perez RM, DeBord KA. Handbook of counseling and psychotherapy with lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Borkovec TD, Costello E. Efficacy of applied relaxation and cognitive- behavioral therapy in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61(4):611–619. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.61.4.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME. Learning and behavior: A contemporary synthesis. Sinauer Associates; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Burckell LA, Goldfried MR. Therapist qualities preferred by sexual- minority individuals. Psychotherapy: Theory, research, practice, training. 2006;43(1):32–49. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.43.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler AC, Chapman JE, Forman EM, Beck AT. The empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Clinical Psychology Review. 2006;26(1):17–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castonguay LG, Beutler LE, editors. Principles of therapeutic change that work. Oxford University Press; 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV and AIDS among gay and bisexual men. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chauncey G. Gay New York: Gender, urban culture, and the making of the gay male world, 1890–1940. New York: Basic Books; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran SD. Emerging issues in research on lesbians’ and gay men’s mental health: Does sexual orientation really matter? American Psychologist. 2001;56(11):931–947. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.56.11.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran SD, Sullivan JG, Mays VM. Prevalence of mental disorders, psychological distress, and mental services use among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(1):53–61. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford J, Cayley C, Lovibond PF, Wilson PH, Hartley C. Percentile norms and accompanying interval estimates from an Australian general adult population sample for self-report mood scales (BAI, BDI, CRSD, CES-D, DASS, DASS-21, STAI-X, STAI-Y, SRDS, and SRAS) Australian Psychologist. 2011;46(1):3–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-9544.2010.00003.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Major B. Social stigma and self-esteem: The self-protective properties of stigma. Psychological Review. 1989;96:608–630. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.96.4.608. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- das Nair R, Butler C. Intersectionality, sexuality and psychological therapies: Working with lesbian, gay and bisexual diversity. West Sussex, United Kingdom: Wiley-Blackwell; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR. BSI 18, Brief Symptom Inventory 18: Administration, scoring and procedures manual. NCS Pearson, Incorporated; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Dobson KS. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of cognitive therapy for depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1989;57(3):414–419. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.57.3.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drescher J. Psychoanalytic therapy and the gay man. Hillsdale, NJ: The Analytic Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg ME, Resnick MD. Suicidality among gay, lesbian and bisexual youth: The role of protective factors. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39(5):662–668. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellard KK, Fairholme CP, Boisseau CL, Farchione TJ, Barlow DH. Unified protocol for the transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: Protocol development and initial outcome data. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2010;17(1):88–101. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eubanks-Carter C, Burckell LA, Goldfried MR. Enhancing therapeutic effectiveness with lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2005;12(1):1–18. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bpi001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farchione TJ, Fairholme CP, Ellard KK, Boisseau CL, Thompson-Hollands J, Carl JR, Barlow DH. Unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: A randomized controlled trial. Behavior Therapy. 2012;43(3):666–678. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman MJ, Cohen JA. Effective treatments for PTSD: Practice guidelines from the international society for traumatic stress studies. New York: Guildford Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Glassgold JM. The case of Felix: An example of gay-affirmative, cognitive- behavioral therapy. Pragmatic Case Studies in Psychotherapy. 2009;5(4):1–21. doi: 10.14713/pcsp.v5i4.995. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldfried MR, Davison GC. Clinical behavior therapy (expanded edition) New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg LS. Emotion-focused therapy: Coaching clients to work through their feelings. American Psychological Association; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hart TA, Heimberg RG. Social anxiety as a risk factor for unprotected intercourse among gay and bisexual male youth. AIDS and Behavior. 2005;9(4):505–512. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML. How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135(5):707–730. doi: 10.1037/a0016441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML. Social factors as determinants of mental health disparities in LGB populations: Implications for public policy. Social Issues and Policy Review. 2010;4(1):31–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2409.2010.01017.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Emotion regulation and internalizing symptoms in a longitudinal study of sexual minority and heterosexual adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008;49:1270–1278. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01924.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Dovidio J. How does stigma “get under the skin”? The mediating role of emotion regulation. Psychological Science. 2009;20(10):1282–1289. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02441.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Pachankis JE, Wolff J. Religious climate and health risk behaviors in sexual minority youths: A population-based study. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102:657–663. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimberg RG, Becker RE. Cognitive-behavioral group therapy for social phobia: Basic mechanisms and clinical strategies. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Herrick AL, Stall R, Goldhammer H, Egan JE, Mayer KH. Resilience as a research framework and as a cornerstone of prevention research for gay and bisexual Men: Theory and evidence. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;18:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0384-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath KJ, Oakes JM, Rosser BS, Danilenko G, Vezina H, Amico KR, Simoni J. Feasibility, acceptability and preliminary efficacy of an online peer-to-peer social support ART adherence intervention. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17(6):2031–2044. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0469-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang WC. The formative method for adapting psychotherapy (FMAP): A community-based developmental approach to culturally adapting therapy. Professional psychology: Research and Practice. 2009;40(4):369–377. doi: 10.1037/a0016240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS, Dobson KS, Truax PA, Addis ME, Koerner K, Gollan JK, Prince SE. A component analysis of cognitive-behavioral treatment for depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64(2):295–304. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.64.2.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones MA, Gabriel MA. Utilization of psychotherapy by lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals: Findings from a nationwide survey. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1999;69(2):209–219. doi: 10.1037/h0080422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaysen D, Lostutter TW, Goines MA. Cognitive processing therapy for acute stress disorder resulting from an anti-gay assault. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2005;12(3):278–289. doi: 10.1016/S1077-7229(05)80050-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Mickelson KD, Williams DR. The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1999;40(3):208–230. doi: 10.2307/2676349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang AJ, Norman SB, Means-Christensen A, Stein MB. Abbreviated brief symptom inventory for use as an anxiety and depression screening instrument in primary care. Depression and Anxiety. 2009;26(6):537–543. doi: 10.1002/da.20471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange AJ, Jakubowski P, McGovern TV. Responsible assertive behavior: Cognitive/behavioral procedures for trainers. Champaign, IL: Research Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Lau AS. Making the case for selective and directed cultural adaptations of evidence-based treatments: Examples from parent training. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2006;13(4):295–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2006.00042.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lick DJ, Durso L, Johnson K. Minority stress and physical health among sexual minorities. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2013;8(5):521–548. doi: 10.1177/1745691613497965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddle BJ. Recent improvement in mental health services to lesbian and gay clients. Journal of Homosexuality. 1999;37(4):127–137. doi: 10.1300/J082v37n04_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen PB, Green R. Gay adolescent males’ effective coping with discrimination: A qualitative study. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling. 2012;6(2):139–155. doi: 10.1080/15538605.2012.678188. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martell CR, Safren SA, Prince SE. Cognitive-behavioral therapies with lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients. Guilford Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129(5):674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH, Schwartz S, Frost DM. Social patterning of stress and coping: Does disadvantaged social statuses confer more stress and fewer coping resources? Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67(3):368–379. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Garofalo R, Herrick A, Donenberg G. Psychosocial health problems increase risk for HIV among urban young men who have sex with men: Preliminary evidence of a syndemic in need of attention. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2007;34:37–45. doi: 10.1007/BF02879919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Garofalo R, Monahan C, Gratzer B, Andrews R. Feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of an online HIV prevention program for diverse young men who have sex with men: The keep it up! intervention. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17(9):2999–3012. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0507-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb ME, Mustanski B. Internalized homophobia and internalizing mental health problems: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30(8):1019–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öst LG. One-session treatment for specific phobias. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1989;27(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(89)90113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE, Goldfried MR. Clinical issues in working with lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients. Psychotherapy. 2004;41(3):227–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.41.3.227. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE, Goldfried MR. Social anxiety in young gay men. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2006;20:996–1015. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE. The use of cognitive-behavioral therapy to promote authenticity. Pragmatic Case Studies in Psychotherapy. 2009;5(4):28–38. doi: 10.14713/pcsp.v5i4.997. [DOI] [Google Scholar]